Abstract

American Indian adolescents have two to four times the rate of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) compared to whites nationally, they shoulder twice the proportion of AIDS compared to their national counterparts, and they have a 25% higher level of teen births. Yet little is known about the contemporary expectations, pressures, and norms that influence American Indian youth or how those might be shaped by today’s lived cultural experiences, which frustrates attempts to mitigate the apparent disparity in sexual health. This paper used data from focus groups, in-depth interviews, and surveys with American Indian adolescents and young male and female adults from a Northern Plains tribe to contextualize sexual risk (and avoidance). Placing the findings within an adapted indigenist stress-coping framework, we found that youth faced intense pressures for early sex, often associated with substance use. Condoms were not associated with stigma, yet few seemed to value their importance for disease prevention. Youth encountered few economic or social recriminations for a teen birth. As such, cultural influences are important to American-Indian sexual health and could be a key part of prevention strategies.

Keywords: Culture, context, sexual risk among Northern Plains American Indian youth, USA, HIV/STDs, Pregnancy

American Indian adolescents shoulder a disproportionate level of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and teen pregnancies. American Indian youth have almost four times the rate of chlamydia compared to their white counterparts, even at young ages (10–14), and twice the rate of whites for gonorrhea (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003a). While, in absolute numbers, AIDS cases among American Indians are low, this population has experienced a more than 10-fold increase since 1990; among American Indians diagnosed with AIDS, youth under the age of 25 comprise 7% compared to 3.5% for the national population (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003b). In 2001, the birth rate for American Indians ages 15–19 was 56.3 per 1000, compared to a national rate of 45.3 (aU.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003a). Thus, STDs, including HIV, and early pregnancy too frequently mark turning points in the lives of American Indian youth. Effective prevention requires grounding not only in the sexual epidemiological profile of this vulnerable population, but also in the culture and context of everyday life in which decisions are made about sexual activity. Some anthropological and historical literature exists on historically traditional courting rituals, marriage rites and expectations, and norms of sexual behavior (Powers, 1986; Shoemaker, 1995), but little is known about the contemporary expectations, pressures, and norms that influence American Indian youth or how those might be shaped by today’s lived cultural experiences.

Here, we adapted Walters and Simoni’s indigenist framework of stress and coping to understand factors shaping the sexual activity of American Indian youth today (Walters & Simoni, 2002). The framework explicitly accommodates culture and changes over time in an evaluation of health outcomes. We also chose to present the case for just one reservation-based tribe to provide an in-depth examination of influential factors on youth sexual behavior for that tribe. Our agreement with this tribe, as with all tribes with which we work, is to protect community confidentiality, often as important to tribes as individual confidentiality (Norton & Manson, 1996). As such, we withhold the name of the tribe, using a general cultural descriptor of “Northern Plains.”

Conceptual framework of health for American Indian youth

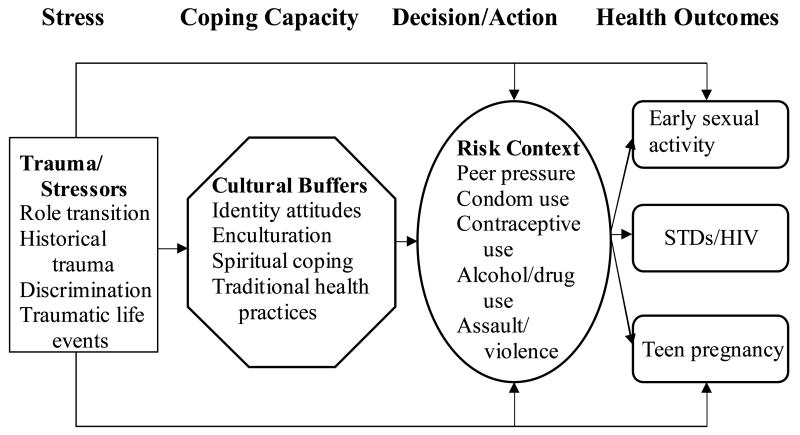

Walter and Simoni (2002) propose a theoretical framework, based on the work of Dinges and Joos (1988) and Krieger (1999), specifically developed to address Native women’s health. In it, they propose a stress-coping model that explicitly incorporates historical and contemporary forces of stress and cultural buffers, such as ethnic identity or spiritual practices. These forces moderate or mediate stressors and strengthen psychological and emotional health and, in turn, mitigate poor health outcomes. In the model, the outcomes are encompassing, including physical health, substance use, and mental health.

We made several adaptations to this model. Prior to data analysis, we specified sexual health outcomes appropriate for youth: early onset of sexual activity, STDs and HIV, and teen pregnancy. As analysis progressed, the items of risk context emerged and appeared to comprise a salient category in the framework for sexual risk. Finally, sexual assault, while clearly a stressor as described in the original formulation, can be closely linked to adolescent sexual activity. Thus, we moved that item from “stressor” to “risk context.” (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of sexual health for American Indian youth

Note: Adapted from Walter and Simoni (2002)

The model we used proposes that the stressors in the lives of American Indian youth include anxiety and conflict from role transitions – everyday events in the lives of most youth that correspond to maturity and increasingly taking on adult responsibilities. Additionally, the traumatic history of American Indians may act as an alienating force on these youth. Some have recognized the massacres, decimation of populations through war and disease, and deculturation policies as “historical trauma,” similar to the holocaust, and have asserted a relationship to health outcomes (Yellow Horse Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998). A growing literature shows a relationship between racially based discrimination and health outcomes (Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003). Whitbeck and colleagues, for example, found a positive relationship between perceived discrimination and substance use in a sample of American Indian 5th–8th graders from the Upper Midwest, and further, that the relationship was mediated by anger and delinquent behaviors (Whitbeck, Hoyt, McMorris, Chen, & Stubben, 2001). Finally, contemporary life on reservations is often punctuated with traumatic events (Manson, Beals, Klein, Croy, & The AI-SUPERPFP Team, 2005). According to Indian Health Service (IHS) statistics (Indian Health Service, 2003) in the region of the present study, accidents and adverse events occurred at over three times the national rate. Indeed, the accumulation of hardship in the American Indian communities has translated into a life expectancy at birth of only 64.8 years in this IHS region, 11.0 years less than the national average.

Cultural buffers refer to those elements of tribal life that provide social, emotional, psychological, and physical strength; they are derived from ritual, myth, symbolism, and traditional healing practices, either individually or in shared experience. Cultural identity, learning and practicing cultural ceremonies, spirituality, and traditional methods of health and healing are examples of cultural resources that American Indian youth may draw upon to help them make healthy sexual decisions. The roles of cultural buffers—what they are, how they intertwine with self-esteem, identity, or health behavior, and how one measures engagement with them—are diverse (Phinney, Lochner, & Murphy, 1990; Roberts, Phinney, Masse, Chen, Roberts, & Romero, 1999). Results from studies of American Indian youth revealed ambiguous associations between cultural identity and risk behaviors (Novins & Mitchell, 1998; Oetting & Beauvais, 1990–91). Further, the relationship between culture and health outcomes likely changes over developmental periods and by risk context (Phinney, 1993, 1996).

Partner pressure to have sex and/or use alcohol or drugs, and sexual assault, are examples of elements that may contribute to the risk context of sexual activity. The framework suggests that understanding risk context, and its relationship to culture and ultimately to outcomes, may provide a means for effectively focusing prevention efforts. Specifically, identifying the elements of the risk context for sexual activity, examining the relationship of cultural buffers to risk context, and delineating the way risk context might then operate to increase (or decrease) the probability of having sex or unprotected sex may suggest points of prevention or intervention for encouraging healthy sexual decision-making among American Indian youth.

In the present analysis, we primarily focused on the last three components of the model: cultural buffers, risk context and health outcomes. For each health outcome, we provide descriptive statistics of patterns and describe the risk context that may have led to that outcome. We then turn to an examination of cultural buffers to risk context and outcomes. Applying the framework in this way may provide a better understanding of sexual risk among youth of this Northern Plains tribe.

Data and methods

We drew primarily from a series of focus groups discussions and in-depth interviews conducted on the reservation from 1993 to 2000. These discussions were particularly useful in that they were embedded within a project collecting quantitative data. We followed a cohort of 518 youth (ages 14 – 19) annually over 7 years, under three linked projects: The Voices of Indian Teens (VOICES, 1993–1995), Pathways of Choices (CHOICES, 1996–1999), and Healthy Ways (HW, 1999–2000). This series of studies began in 1993 with a school-based cohort of high school students, coupled with active community-based follow-up. Each project included only a few interviews or group discussions, intended to inform quantitative analyses of each project. However, collectively, they represent a wealth of information on sexual health among American Indian youth yet to be presented. (See Table 1.) All respondents gave consent or assent, and parental consent was obtained for minors.

Table 1.

Sample overview by project

| Project+ | Approx ages* | Dates | Survey (# of waves) | Focus Groups | In-depth Interviews | Sampling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voices of Indian Teens (VOICES) | 14–19 | 1993–95 | Annual (3) | None | 2 female; 4 male | Randomly selected from survey sample |

| Pathways of Choice (CHOICES) | 16–21 | 1996–99 | Annual (4) | 4 female | None | Randomly selected from survey sample |

| Healthy Ways (HW) | 19–24 | 1999–2000 | HIV questions added to final CHOICES survey | 2 female; 2 male | 2 female; 1 male | Community members recruited by local staff** |

All participants gave consent or assent. If minors, parental consent was first obtained.

Age distribution reflects that of the first wave of data collection for each project. Original sample selected by grade (9–12), not age. Due to grade repetition, large age variations occur within a single grade.

To maximize confidentiality, HW respondents were informed they would not be re-contacted.

The discussions were open-ended, and broadly covered topics of risky behaviors including sexual risk-taking; issues surrounding STDs, HIV, and teen pregnancy; and cultural influences on sexual activity. We held 8 discussion groups in total, and 9 in-depth interviews. Ages for the group discussions ranged from 18 to 25. Conversations in these groups commonly referenced earlier teenage years. Each group included 5 to 10 respondents. We also spoke to several adolescents in in-depth interviews to ask about particular current experiences and perspectives that they might have. We spoke to males (2 groups, 5 in-depth interviews) and females (6 groups, 4 in-depth interviews) separately. Group discussions were not intended to provide representative information; they were instead intended to provide norms, ideals, and the bounds of experiences – that is, extreme cases. In-depth interviews provided detail on specific experiences or ideas that were not easily revealed in group discussion. Tapes were transcribed and all transcripts were reviewed and independently coded by at least two project team members using standard word processing packages. Main themes also were identified independently by two team members and then compared for verification and, when necessary, were reconciled. Staff members who were tribal community members reviewed the results of coding and analysis to assure face validity from a tribal perspective.

The quantitative data from these linked projects have provided a rich source of information about health of these youth (Mitchell, Kaufman, & Beals, 2005; Novins, Beals, & Mitchell, 2001), though none have focused on descriptive or qualitative data. We used data from the first survey of CHOICES, when most respondents were in the age category of 16–21, to present a profile of sexual risk-taking as teenagers entered early adulthood. We used simple descriptive and test statistics in Stata (StataCorp, 2003) to characterize the sample and sexual risk indicators. To provide a comparative context to illustrate the points of risk for this group, we referenced results of the 1997 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBS) for 11th and 12th graders (Kann, Kinchen, Williams, Ross, Lowry, Hill, et al., 1998). Important methodological differences exist between the two studies. For example, the YRBS, a nationally representative sample of over 16,000 high school students, sampled younger respondents than CHOICES did, and participants were all enrolled in school (none of the sampled schools in the YRBS were located on American Indian reservations). CHOICES included youth regardless of enrollment status, although enrollment was a requirement for recruitment into the sample initially. Still, using similar age groups, comparisons are illustrative. We summarize the statistics in Tables 2 and 3. We weave the relevant statistics into each section below. For each interview quote, we note the age and gender of the respondents in interviews. All focus group participants were between the ages of 18 and 25, so we only note gender for quotes for these discussions. Unless otherwise specified, no participants were quoted more than once.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics, Northern Plains young adults

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 518 | 100 |

| Male | 246 | 47 |

| Female | 272 | 53 |

| Age | ||

| 16 | 30 | 6 |

| 17 | 83 | 16 |

| 18 | 143 | 28 |

| 19 | 118 | 23 |

| 20 | 82 | 16 |

| 21+ | 62 | 12 |

| Education | ||

| No degree/not currently attending | 59 | 11 |

| Currently attending GED/HS | 198 | 38 |

| Received GED/HS diploma | 258 | 50 |

| missing | 3 | 1 |

Note: Data from CHOICES, wave 1 (1996).

Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Table 3.

Selected indicators of sexual risk by gender, Northern Plains American Indian young adults

| Ever had sex | N | Total | Males | Females | Prob | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHOICES | Complete sample | 510 | 82.6% (421) | 86.0% (208) | 79.5% (213) | 0.054 |

| 19+ years old | 257 | 92.2% (237) | 93.2% (124) | 91.1% (113) | 0.529 | |

| <=18 years old | 253 | 72.7% (184) | 77.1% (84) | 69.4% (100) | 0.178 | |

| YRBS** | 11th and 12th gr | na | 55.3% | 54.7% | 56.1% | ns |

| Had sex before age 13, among those who had sex | ||||||

| CHOICES | Complete sample | 400 | 9.5% (38) | 16.9% (34) | 2.0% (4) | 0.000 |

| 19+ years old | 228 | 10.53% (24) | 18.33% (22) | .9% (1) | 0.000 | |

| <=18 years old | 172 | 8.1% (14) | 15.0% (12) | 2.2% (2) | 0.000 | |

| YRBS | 11th and 12th gr | na | 5.4% | 7.1% | 3.2% | + |

| Used alcohol/drugs at last sex, among those who had sex | ||||||

| CHOICES | Complete sample | 412 | 26.5% (109) | 35.1% (72) | 17.9% (37) | 0.000 |

| 19+ years old | 233 | 26.2% (61) | 35.8% (44) | 15.5% (17) | 0.000 | |

| <=18 years old | 179 | 26.8% (48) | 34.2% (28) | 20.6% (20) | 0.042 | |

| YRBS | 11th and 12th gr | na | 23.2% | 28.5% | 17.7% | + |

| Used condom at last sex, teenagers only, among those who had sex | ||||||

| CHOICES | Complete sample | 421 | 37.3% (157) | 47.1% (98) | 27.7% (59) | 0.000 |

| 19+ years old | 237 | 31.7% (75) | 44.4% (55) | 17.7% (20) | 0.000 | |

| <=18 years old | 184 | 44.6% (82) | 51.2% (43) | 39.0% (39) | 0.097 | |

| YRBS | 11th and 12th gr | na | 56.2% | 63.0% | 49.2% | + |

| Had 4 or more sexual partners over lifetime, among those who had sex | ||||||

| CHOICES | Complete sample | 340 | 44.7% (152) | 59.9% (94) | 31.7% (58) | 0.002 |

| 19+ years old | 186 | 46.2% (86) | 55.3% (52) | 37.0% (34) | 0.258 | |

| <=18 years old | 154 | 42.9% (66) | 66.7% (42) | 26.4% (24) | 0.000 | |

| YRBS | 11th and 12th gr | na | 18.7% | 19.0% | 18.2% | ns |

| Have been pregnant or have gotten someone else pregnant, among those who had sex | ||||||

| CHOICES | Complete sample | 400 | 38.5% (154) | 26.4% (51) | 49.8% (103) | 0.000 |

| 19+ years old | 225 | 49.5% (109) | 31.9% (37) | 66.1% (72) | 0.000 | |

| <=18 years old | 175 | 25.7% (45) | 18.2% (14) | 31.6% (31) | 0.032 | |

| YRBS | 11th and 12th gr | na | 7.7% | 5.6% | 10.0% | + |

CHOICES, wave 1 (1996). Percentages are based on column percents. Ns for each question vary due to missing data in self-administered survey. Statistical tests are based on chi-squared distributions of gender differences.

Youth Risk Behavior Survey (1997), 11th and 12th grade only. Percents adjusted and weighted. No specific N’s provided for each question; total sample N=16,226.

Significant gender difference, p<.05, based on published 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Risk context and early sexual activity among Northern Plains youth

Historically, opportunities for male and female socializing were limited. Courting, for those who had reached puberty and had passed through ceremonies marking adulthood, was strictly supervised. While premarital sex was not unheard of, and was tolerated if a couple had committed to marriage, virginity until marriage was valued (Bataille & Mullen Sands, 1984). Currently, few threads of traditional courtship remained and puberty rites have virtually disappeared.

Well, you know around here it’s, you know, guys and girls don’t go out on normal dates. It’s – hey, let’s go have a party and get drunk and do it, you know? It’s not let’s go out and see a movie…it’s the party.

(Female group)

Participants agreed that sex often was not a result of a physical or emotional progression or a part of “normal dates.” Sexual activity, according to our participants, was simply something that occurs among all youth, and often at young ages. It’s what “young kids do today.”

My sister is 14, she’s not sexually active or anything…She said a lot of 13- and 14-year-olds are sexually active, and some have babies already.

(Female group)

Facilitator (F): How old do you think kids are these days when they start having sex?

Everyone: Twelve.

F: How old do you think they should be?

J: Twenty.

L: Fifteen or sixteen.

S: When they know they’re responsible. Or when they don’t think they have to do it just because everyone else is doing it.

(Female group)

The survey data indicated that these observations may be true for some. For example, in the CHOICES sample, 15.0% of boys and 2.2% of girls 16–18 had had sexual intercourse before the age of 13 (p<0.0001). This level was more than twice the level reported for 11th and 12th grade boys in the YRBS (7.1%), yet lower than that for YRBS girls (3.2%). Overall, 72.7% of those 16 to 18 in the CHOICES sample had had sex at least once in their lifetimes, more than 30% higher than that of the YRBS 11th and 12th graders (55.3%).

Age itself was not generally regarded as an appropriate marker of transitions by many of the participants. Instead, appropriate age for sexual activity, or other role transitions, was described in terms of maturity – in this case, the ability to resist peer pressure, especially for the first time. This included pressure to “be like everyone else” and to “prove” that one was grown up.

Me, I never had sex before but it’s like your friends pressure you into it, like, “I lost mine. Why don’t you lose it? Just try it out.” Like some of the guys, they consider you a little girl if you don’t have sex here. Like, “She’s just a little girl.” If you like somebody and you ask them out, “She’s just a little girl.” It’s all the guys want here is that. That’s all they want.

(Female interview, 14)

Finally, respondents were also clear that reasons motivating such activity were deeply rooted; it was for particular reasons that some youth were more vulnerable to peer pressure at young ages.

I think a lot, too, that has to do with the reason why kids are having sex so young and babies so young is that a lot of it has to do with maybe their self-esteem, self-respect. I mean, because they come from broken families or maybe they’re not paid much attention to or they don’t have a stable home. Some are looking to escape from home, and by going out and finding someone to live with or a boyfriend or girlfriend, they try and take whoever and try and replace their family with a different family. But always looking for acceptance, trying to find someone who loves them, whether it be a guy or having a kid who they think is going to love them and you can.

(Female group)

As in the quote above, many participants talked about apparent pervasive sexual activity among youth within the context of a loss of connection – with their families, with their culture, or with their communities. While these youth were likely to share many of the challenges to identity formation and solidify self-esteem and confidence of youth in other settings, unique social and historical factors, such as an imposed educational policy of deculturation, may have permeated these youths’ life experiences.

Many sexually risky situations described by youth included alcohol or drugs. Indeed, substance use is frequently a co-factor in early sexual experience and unsafe sexual practices in many settings (Santelli, Robin, & Lowry, 2001), although little is known about its relationship with risky sex among American Indian youth (Beauvais, 1992). For those aged 16–18 in CHOICES, 34.2% of boys and 20.6% of girls (p=.042) reported using alcohol or drugs at last sex. The gender difference was found to increase with age. Comparatively, in the YRBS, 28.5% of 11th and 12th grade boys and 17.7% of girls reported using alcohol or drugs at last sex.

Parties are where youth drank and tried to “hook up,” or have sex, with someone. The experiences reported by our participants indicated that alcohol or drug use was tightly tied to sexual activities for youth.

Interviewer (I): Does it [alcohol] always lead to sex?

D: For the young people I think. ‘Cause they all have their big party and raise hell. When I was younger, it was like just one big party and then try to hook up with someone.

(Male interview, age 22)

…a lot of sex happens under the influence. At least with me, that’s how it was. Because we all liked to go around and just get bored and then nothing to do, and they cruise around and nothing to do so they just go straight to drinking. Then that leads to sex. It just always does; it just always did for me. And then you get drunk and then this guy – when you first start drinking, he’s just ugly and then by the third beer he’s all right, and by the sixth beer he’s fine. And then you make your move.

(Female group)

While “hooking up” may have been discussed as if it was a game or a goal for a night—for both girls and boys—intoxication provided immense opportunity for assault and abuse. The following account of “training,” or gang rape, is particularly disturbing.

A: Like there’s a couple of girls in, let me think, sixth and seventh grade having sex that I know of. I mean, whenever they have sex it’s usually when they’re drunk because, like, those guys train them. That means, like, a whole bunch of guys have sex with them one after another, with those girls.

I: Yeah. Do girls, I mean, do the boys get them drunk on purpose?

A: Yeah. I used to have a friend…but like they call her a drunk whore. That’s the only way I can say it, but I don’t know… I told her that, never to go with nobody when she’s alone, and she did and they [trained] her. Then after that she, I mean, she didn’t do it whenever she was sober. She’d do it when she was drunk…Because they would get her drunk, and that’s what they do still…

(Female interview, 15)

Many participants mentioned training as an extreme example of what happens when sex and alcohol mix. It is important to note, however, that although such incidences may not be singular, it is unknown how frequent such activities occur. Precisely because of the severity of “training,” the event may seem especially worth noting in an interview setting.

Not all American Indians youth have sex at young ages and, when they do, it is not always under the influence. As noted, the percent of those reporting alcohol or drug use at last sex is roughly equivalent to that found nationally in the YRBS, especially for girls. An important lesson from these data, regardless of quantifiable associations, is that the youth participating in our discussions perceived an inevitable link between getting drunk and having sex. Participants also added comments about “rules” to follow to keep safe in risky situations.

I: It seems to me that your boyfriend probably wants to have sex with you?

A: But he knows I won’t. I told him I wouldn’t.

I: And even if you’re drunk?

A: Yeah, he knows. I mean, I won’t get drunk with him. I know better than to get drunk.

I: So you’re drinking with him.

A: Yeah, I’ll just drink with him but I won’t get totally drunk.

(Female interview, 14)

Sexual activity among youth, for these participants, was described as though it were a “given,” or simply a part of growing up. A substantial proportion of youth did engage in sexual activity when quite young. We do not know how much abuse or sexual assault may have contributed to those figures. However, the youth we spoke with easily identified potentially risky situations that might involve sex. Given such situations, participants also described strategies—effective or not—by which youth could protect themselves, an auspicious sign for prevention efforts.

Risk context and STDs/HIV

For this tribe, the positivity rate of chlamydia infection in 2001 was about 18% for those ages 19 or younger. The comparable non-tribal rate, based on clinics in the region serving primarily non-Indian patients, was 3% (bU.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003b). For this tribe, 50% of all chlamydia cases occurred among those aged 15 to 19 (IHS Epidemiology Program, 2004). For the youth in this sample, a diagnosis of an STD was not of much apparent concern. STDs are perceived as medically treatable without long-term consequences.

I: Do kids worry about diseases, HIV? Does that come up in conversations?

H: I don’t think so, they sit around and talk about getting pregnant.

I: Has anyone talked to you about STDs?

H: A friend, two friends. Then they went back to the person and get it again…I say why do you go back? They don’t know, they just keep getting it and getting it, the guys don’t go to the clinic.

(Female interview, age 20)

Yeah there’s some that have STDs and the guy wouldn’t care. People would know it and still go out with them, that’s gross. They was like so what? Go to the hospital because it’s curable.

(Female interview, age 22)

HIV is also an STD; yet this disease was, for most, a distant disease, one that participants in these discussions did not link with other STDs and one they thought would not likely affect them or anyone they knew.

In spite of the deleterious sexual health outcomes—STDs, HIV/AIDS, teen pregnancy—that were often acknowledged in our discussions, questions about condom use commonly elicited shrugs. Condom use, according to the participants, was dependent not on the understanding of the importance of using condoms – most agreed that in theory, condom use was good – but on convenience.

R: You wouldn’t care [about using a condom] ‘cause you have your beer goggles on.

T: You’re too drunk.

I: Is that in general true? It’s whether a condom is handy? Or whether you feel like it or not?

T: Yeah

Y: Yup, if I had one, I’d use it, if not, then I don’t know.

(Male group)

Overall, these statements were supported by the survey data. Of those who had had sex in the CHOICES sample, 37.3% had used a condom at last sex—47.1% of boys, and 27.7% for girls (p<0.0001). Limiting ages to 18 and younger, these rates rose to 51.2% and 39.0% for boys and girls respectively (p=.092); however, they were still considerably below rates found in the YRBS 11th – and 12th-grade sample (63.0% for boys, and 49.2% for girls).

Part of using a condom is communicating with a partner. Participants were not unified on communication with partners about diseases or condom use. Most agreed that at parties, little conversation occurred and probably even less condom use.

I: Do guys and girls talk to each other about protection?

D: Not really. It’s just like a one-night hook-up thing. That’s what I think of it as. It’s just a constant thing. You see it all the time when people are drinking. It’s just like they hook up for that night. They don’t care.

(Male interview, age 22)

However, other respondents reported they were able to talk to their partners about condoms or other means of contraception. One respondent reported she and her partner agreed to be tested every three months, since they did not always use a condom. Others reported that condom use was primarily up to the female, but that males did not protest once they are asked to use a condom. Several boys, however, brought up the importance of using condoms for themselves.

C: I always use rubbers but I don’t want no d*** AIDS or nothing. That’s the way I see it…. It’s a different kind of d*** disease going around.

I: Is it embarrassing to go out and buy condoms?

C: No. I mean sh**, they know you’re taking care of yourself.

(Male interview, age 17)

In no discussion about condoms was there mention of shame, dirtiness, infidelity, or disrespect with use of condoms. In general, the participants agreed that if a condom were available, neither party would resist use. The obstacle was availability and, often, the presence of mind “in the heat of the moment” to think of using a condom.

Some community members have associated contraceptives with population loss or consider contraceptives counter to tribal ideals of life and birth; they have counseled against their use (Lawrence, 2000; Niethammar, 1977). However, in these discussions, condom use specifically has also been identified with disease protection and has been linked to self-respect and dignity among youth. “Self-respect” and “dignity,” in turn, are closely associated with cultural tradition and pride. Some youth mentioned that even their grandparents, with respect to sexual activity, told them that they need to “take care of” and “protect” themselves.

Multiple partnerships were common among these youth and comprised another important sexual risk factor. The reported number of lifetime partners was high in the CHOICES sample. About 66.7% of boys and 26.4% of girls aged 16–18 in the CHOICES sample reported having had four or more partners in their lifetimes (p<0.0001). For 11th and 12th graders in the YRBS, 19.0% of boys and 18.2% of girls reported having had that many partners. References to “sleeping around,” “hooking up” with different partners at different parties, or, for girls who are pregnant or mothers, “not knowing who the father is” are common references to multiple partnerships.

Or these guys go out and get these girls drunk and have their way with them. And then some don’t know who their baby’s from. I knew girls like that. Some girls have kids and don’t know who the father are. Some say they went to a party and got pregnant. It’s funny because they go to a party, get drunk and have sex with a guy they don’t know and have a kid and they don’t know who he is or remember him. (Female interview, age 22)

Few offered a standard or a typical number of partners; few identified a number that indicated too many partnerships. Youth in these discussions did not seem to view many partners as good or bad for themselves but talked about each partnership as an isolated event – without expressed recognition of the cumulative risks.

Risk context and early pregnancy

Pregnancy or paternity was high among these Northern Plains youth. Considering only the 16- to 18-year-olds, 31.6% of girls reported being pregnant at least once, and 18.2% of boys reported having gotten someone pregnant. These rates reflect over 3 times the levels of pregnancy or paternity reported by 11th and 12th grade girls (10.0%), and boys (5.6%) in the YRBS. Historically, childbearing probably began young, at 16 or 17, depending upon marriage arrangements. While virginity until marriage was valued, children born to unmarried couples were not ostracized, especially if the couple intended to marry one another in the future (Powers, 1986). This acceptance may also have been associated with the special status accorded newborns. Their inability to speak was thought to place them close to the spirit forces of the universe: babies were associated with sacred power (Powers, 1986). That high value placed on children remained strong in this community. However, teen pregnancy was commonly mentioned as a problem on the reservation.

To participants, teen pregnancy was a problem associated with having babies in high school – or earlier; older teenagers were not necessarily too young. High school was seen as a time to be wild, a time without responsibility. Once one had graduated from high school, qualifications for parenthood centered on the ability to care for the child, most often described in emotional terms rather than financial ones. According to the participants, support of the family was almost a given for any age of first parenthood. While a teen pregnancy itself was usually not a celebrated event, especially at young ages, the birth of a baby into the family was. Respondents in our discussions routinely noted that the baby was usually absorbed into the larger family network, often with few consequences for the mother or father.

I: What do the rest of you think about having kids in high school? Is that a good age?

D: It’s not a good age, because they’re still young. But if they have more support, then – I mean, my sister was 16 and she had her baby, and me and my mom was all there for her. We encouraged her to go back to school, and she did and she graduated this year. But she did finish high school. So I mean. As long as they have that support – (Female group)

Perhaps because of strong family support, financial security was not always listed as an important marker of being ready for parenthood. Rather, emotional security and maturity were the valued attributes for having a baby.

I love the age I had my son. I wasn’t financially ready, but the age was good. Because if I would have had him like when I was in high school, I would have been too young because my sister has kids and she’s younger than me and she wasn’t ready; I can see that. (Female group)

Within the boundaries of acceptability – waiting to have a child until after high school – the high value placed on children coupled with support of family makes the prospect of relatively early age of childbearing desirable to many. For many, the desire for a child may in fact directly conflict with disease prevention afforded by a condom, which may make messages about consistent condom use particularly challenging to deliver. This young woman, for example, stopped using condoms with her partner because they wanted a baby. She was 18 when she became pregnant.

F: So, did you quit using condoms to get pregnant, or was this –

W: Yeah. I got off birth control, not birth control, but like condoms… But, yeah, we stopped using a condom. It took a while, but eventually [I got pregnant]. (Female group)

Teen pregnancy in this tribe was not the disruptive or condemning experience that it is in many other settings; youthful childbearing may not entail the costs or burdens that often exist elsewhere.

Role of cultural buffers

Youth from this tribe described pressures and expectations that were immensely challenging. Within the context of substance use, these youth seemed to face sexually risky situations continually. However, throughout the conversations, these youth also acknowledged the strong role that culture could play, often described in terms of family relationships and role models. Sometimes, these role-model relationships were explicitly described in “traditional” terms.

[My aunt and uncle are] real traditional, and – they’re what I guess they call old-fashioned, but not old-fashioned – I mean old-fashioned traditional; that’s how they are, their relationship is… They’re really meant to be together, and I love being up there; I love going out to his house. I wish I could live with them.

(Female group)

Other participants spoke broadly about culture and the influence it can have on risky activities.

It kind of depends on the culture. If you’re involved in your culture. I’m drug- and alcohol-free. I don’t even have the time for anything like that. I have a lot of things going for myself. I’m with my culture, but I’m drug- and alcohol-free so I can be a role model for the younger people.

(Male group)

Notably, culture as described by these participants was not always associated with risk avoidance. For example, one respondent mentioned that having a baby young was part of the culture and was traditional. Another likened gang activities to being a warrior, and another made an association between multiple partners and “hunting.” These were not widespread beliefs, and most believed that cultural traditions were counter to risk behaviors common to youth in their communities. Still, these observations showed that culture was by no means a uniform concept, even within this one tribal community.

Discussion

The conversations with these American Indian youth indicated both promising paths of prevention, and apparent conflicts in context and consequences of sexual activities. Virtually all participants made a link between alcohol or drugs and sexual activity; many youth noted strategies they try to use to protect themselves in risky situations that included substances. Similarly, condom use appeared to be increasingly associated with respect, both for self and for one’s partner, even though condom use appeared to be low and inconsistent. In both these cases, youth identified risk situations, and provided hints for effective prevention efforts.

At least three points of tension emerged from these discussions. The study showed that teen pregnancy was by no means understood as universally damaging. Families welcomed newborns and saw to their care, often with very little interruption in the young parents’ lives. Within this community, however, there were boundaries of acceptability for young child-bearing, including educational status (usually of the mother). These youth indicated that sometimes the circumstances of conception may shape acceptability too, for example, if the pregnancy was a result of “hooking-up” at a party, especially when the father is unknown. Our data do not permit an assessment of the role of paternity, however. It could be, for example, that knowing who the father is, regardless of whether he subsequently contributes to the child’s rearing or not, might shape the acceptability of the pregnancy (and ultimately the health of mother and child).

Second, the late teens and early 20s were associated with increases in sexual risk-taking, including inconsistent condom use and multiple partnerships. It is this age for which the message of consistent condom use may be most important. However, condom use at this age may be in direct conflict with family-building plans, no matter how undefined those plans may be – a “condom conundrum” (Preston-Whyte, 1999). Messages of condom use associated with avoiding pregnancy and disease are unlikely to be salient to someone who is thinking of a pregnancy.

Finally, “culture” appears to filter through a gradient of situations, with differential affects on health outcomes. Culture may increase feelings of alienation and thereby increase risky behavior. Alternatively, culture may present a set of resources from which youth can draw to increase their likelihood of making healthy choices. The apparent contradiction may be resolved through a closer inspection of identity formation itself. Phinney (1993), for example, proposes a 3-stage model of ethnic identity formation in adolescents in which adolescents progress through a stage of unexamined identity; a stage of searching, in which they become more aware of strengths of their culture and of differences from the mainstream culture; and finally a stage of ethnic identity achievement, characterized by a confident sense of one’s own identity. The model is a provocative one for this case. Youth generally understood sexual risk as compromising the expectations of their culture. These youth seemed to understand a cultural conflict between traditional activities (during which substances and risk behaviors were not appropriate) and risky activities (in which culture was apparently absent or at least ignored). Thus, it is possible that many of these youth may have been transitioning from the stage of little cultural awareness to the stage where they were searching for cultural meaning in their lives. Many either had not realized the links between cultural expectations and their own actions (or identities) or had begun to experience the tension between their culture and mainstream values. A heightened awareness of one’s own minority status within larger society may produce a distancing of self from culture; distancing thus may be common in risk-taking situations. Some of the youth in this study appeared to have reached a stage of achievement, living in a way they saw as congruent with the expectations of their culture, even within a sometimes hostile mainstream context. In short, youth likely called on cultural resources in their lives, but may have invoked those resources differently (or not at all) depending on an interaction between their stage of identity formation and the situation. Cultural identity – specifically, positive cultural identity formation – could thus be a potent force in prevention efforts.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have used the words of youth themselves to frame the statistics from surveys. Such an approach is not without limitations. Our data represent only one tribe, and our findings are not likely to be generalizable to other tribes. However, these American Indian youth faced many challenges that often transcend tribal differences. Those participating in our discussions were not randomly selected, and so their views also were not likely to be representative of all youth within this tribe. Finally, the conceptual framework guiding the analysis did not guide data collection activities; specific aspects of the framework were not evenly investigated across interviews or focus groups. For example, sexual assault was not always discussed, even though it is likely to be an important factor (Manson, et al., 2005). Still, together, the survey data and the stories shared with us provide the context of sexual risk taking and decision-making for a group with high reproductive morbidity.

The adaptation of Walters and Simoni’s indigenist framework of stress and coping proved to be a useful guide to explore the domains of sexual health in this vulnerable population. The analyses carried out here suggest several specific future research paths. Gender differences in understanding of risk context and its relation to reproductive outcomes may be particularly important. For example, in discussions on teen pregnancy, girls tended to focus on a prospective mother’s maturation, and the help provided to many teen mothers by family. Boys spoke little of the responsibilities of parenthood. Understanding the role of paternity and responsibilities of young fatherhood may be critical to the health and well-being of young mothers and their babies. Another area requiring further investigation is that of abuse and sexual assault among youth. Both boys and girls talked about the abusive elements of sexual activity at young ages, especially related to alcohol use; yet, we know little about this abuse – the extent, age differentials, or physical and emotional consequences. Finally, the role of culture in preventing or promoting sexual activity remains ambiguous. Here, comparative work with youth from other ethnic groups may prove fruitful.

Many of the stories reported in these pages are troubling, yet these young people also spoke of youth who made healthy decisions even in the face of great pressure to do otherwise. The experiences both of strength and of mistakes are important in understanding choices American Indian youth make.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Voices of Indian Teens, Pathways of Choices, and Healthy Ways Project Teams. We are also indebted to many participants who so generously gave of their time to openly share with us their thoughts and experiences.

This research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R01 AA08474, National Institute on Child Health and Human Development grant R01 HD33275, a supplement to HD33275 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the National Institute of Mental Health grants R01 MH59017 and R01 MH69086.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bataille GM, Mullen Sands K. American Indian women: Telling their lives. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais F. The consequences of drug and alcohol use for Indian youth. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 1992;5:32–37. doi: 10.5820/aian.0501.1992.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease and surveillance, 2002. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2003a. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. 2002. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2003b. [Google Scholar]

- Dinges N, Joos S. Stress, coping, and health: Models of interaction for Indian and Native populations. In: Manson S, Dinges N, editors. Behavioral health issues among American Indians and Alaska Natives: Explorations on the frontiers of biobehavioral sciences. Denver: National Center for American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center; 1988. pp. 8–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IHS Epidemiology Program. Stop Chlamydia! Use Azithromycin Program. Albuquerque: Indian Health Service; 2004. Unpublished report. [Google Scholar]

- Indian Health Service. Regional differences in Indian health, 2000–2001. US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen SA, Williams BI, Ross JG, Lowry R, Hill CV, Grunbaum JA, Blumson PS, Collins JL, Kolbe LJ. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance--United States, 1997. MMWR CDC Surveillance Summary. 1998;47(3):1–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Embodying inequality: A review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. International Journal of Health Services. 1999;29(2):295–352. doi: 10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence J. The Indian Health Service and the sterilization of Native American women. American Indian Quarterly. 2000;24:400–419. doi: 10.1353/aiq.2000.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM, Beals J, Klein SA, Croy CD The AI-SUPERPFP Team. Social epidemiology of trauma among 2 American Indian reservation populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(5):851–859. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CM, Kaufman CE, Beals J. Resistive efficacy and multiple partners among American Indian young adults: A parallel-process latent growth curve model. Applied Developmental Science. 2005;9:160–171. [Google Scholar]

- Niethammar CJ. Daughters of the earth: The lives and legends of Indian women. New York: Collier Books; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Norton IM, Manson SM. Research in American Indian and Alaska Native communities: Navigating the cultural universe of values and process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:856–860. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novins DK, Mitchell CM. Factors associated with marijuana use among American Indian adolescents. Addiction. 1998;93:1693–1702. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931116937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novins DK, Beals J, Mitchell CM. Sequences of substance use among American Indian adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1168–1174. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Beauvais F. Orthogonal cultural identification theory: The cultural identification of minority adolescents. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1990–91;25:655–685. doi: 10.3109/10826089109077265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Lochner BT, Murphy R. Ethnic identity development and psychological adjustment in adolescence. In: Stiffman AR, Davis LE, editors. Ethnic issues in adolescent mental health. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. A three-stage model of ethnic identity development in adolescence. In: Bernal ME, Knight GP, editors. Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1993. pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity and self-esteem: A review and integration. In: Padilla AM, editor. Hispanic psychology: Critical issues in theory and research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996. pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Powers MN. Oglala women myth, ritual, and reality. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Preston-Whyte E. Reproductive health and the condom dilemma in South Africa. In: Caldwell JC, editor. Resistances to behavioural change to reduce HIV/AIDS in predominantly heterosexual epidemics in third world countries. Canberra: Health Transition Center, National Center for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australia National University; 1999. pp. 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero A. The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19(3):301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Robin L, Lowry R. Timing of alcohol and other drug use and sexual risk behaviors among unmarried adolescents and young adults. Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;33(5):200–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker N. Negotiators of change: Historical perspectives on Native American women. New York: Routledge; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata v9.0, special edition. College Station, Texas: Stata Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. [accessed 07-12-04];Health, United States, 2003, with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. 2003a Http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus.htm.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Stop Chlamydia! Use Azithromycin program. 2003b. Chlamydia surveillance information for the <tribal> IHS Indian Hospital, 01/01/2003-06/30/2003: IHS/CDC report. [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Simoni JM. Reconceptualizing Native women’s health: An “indigenist” stress-coping model. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:520–524. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, McMorris BJ, Chen X, Stubben JD. Perceived discrimination and early substance abuse among American Indian children. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2001;42(4):405–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson J. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellow Horse Brave Heart M, DeBruyn LM. The American Indian holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 1998;8(2):56–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]