SYNOPSIS

In March 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) convened a consultation meeting to explore microenterprise as a potential human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) prevention intervention. The impulse to link microenterprise with HIV/AIDS prevention was driven by the fact that poverty is a significant factor contributing to the risk for infection. Because increasingly high rates of HIV infection are occurring among women, particularly among poor African American women in the southern United States, we focused the consultation on microenterprise as an intervention among that population.

In the international arena, income generated by microenterprise has contributed to improving family and community health outcomes. This article summarizes the contributions made to the consultation by participants from the diverse fields of microenterprise, microfinance, women's studies, and public health. The article ends with recommendations for HIV/AIDS prevention and, by implication, addressing other public health challenges, through the development of multifaceted intervention approaches.

Health may be considered a multisectoral issue, involving access to care and services, transportation, health insurance of some type, education, individual and family well-being, housing, and community-level issues such as neighborhood safety. Concomitantly, many health problems are exacerbated by the poverty that impacts family and community well-being.

While poverty is associated with increased risk for multiple adverse health outcomes, it is typically not directly addressed in public health interventions. Similarly, whereas microenterprise is a fairly widespread approach to poverty alleviation, it is not generally considered a public health intervention. Broadly speaking, microenterprise is the practice of making small loans and providing financial literacy to the poor—predominantly to women—to help them achieve economic self-sufficiency. The microenterprise goal of relieving poverty can be seen as a corollary to a comprehensive approach to public health.

In March 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) convened a multisectoral consultation meeting to link microenterprise and public health, specifically to consider microenterprise as a potential human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) prevention intervention among impoverished African American women at risk for HIV—a population that recently has experienced sharply increased rates of HIV infection. This article briefly summarizes that meeting and includes recommendations for public health activity that is directly responsive to a broader socioeconomic and structural context influencing women's risk for HIV/AIDS.

In an era of small government budgets, we may be somewhat forced to address the complex linkages between poverty and health outcomes through broad collaborations among agencies and community groups that typically work in silos. But that collaborative approach has often been recommended by public health practitioners and is, at the same time, exciting in its possibilities. And while the collaborations proposed here are focused on HIV and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) among women in poverty, the implications for other populations and health issues are salient and profound.

BACKGROUND

African American women are vastly overrepresented in the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the U.S. Whereas African Americans represent 13% of the U.S. population,1 they account for 50% of new HIV/AIDS infections.2 Among women, African Americans represent 68% of new HIV infections2 and are 21 times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV than white women.3

In recent years, racial disparities in the HIV/AIDS epidemic have also been associated with regional disparities, with disproportionately more cases of HIV and AIDS being reported in the South than in other regions of the U.S.2 In addition to high rates of HIV and AIDS, there is a higher prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among African Americans compared with other groups in this region.4 At the same time, states in the South are among those with the highest rates of poverty, unemployment, and lack of health insurance in the U.S.5 The South represents 36% of the total U.S. population, yet accounts for 43% of Americans living in areas with high poverty rates.6 The positive correlation between poverty and poor health (indicated by population measures of morbidity and morality) has been well-documented. Therefore, as might be expected given this link, southern states also tend to have higher income-related health inequality and poorer overall health achievement, defined as improvement in health status among specific populations.7

In fact, among the factors that affect health status among African Americans—such as inadequate health insurance and limited quality care8—poverty appears to be a primary underlying factor and, as such, contributes to the risk for HIV infection among African American women in the South.9 That is, at this point in the U.S. epidemic, women at risk for acquiring or transmitting HIV or other STIs disproportionately live in poverty,9–13 and the dynamic or pathways leading from poverty to HIV/STI risk are often complex, as described in Adimora and Schoenbach's 2005 review article on the facilitative role of social context in HIV/STI transmission within heterosexual networks.14

For example, chronic poverty, residential segregation, and sex roles may combine to propel some women into the informal economy—including trading sex for commodities and for survival needs such as housing and food—and greatly influence relationships with children and intimate partners.9,14–20 Dense sexual networks, often characterized by concurrent partnerships, are supported by socioeconomic factors such as economic oppression, racial discrimination, high incarceration rates of black men, and the “striking low”14 ratio of men to women in African American communities.9,14 Some impoverished women use illicit drugs, such as crack cocaine and heroin, which greatly increases the risk for HIV/AIDS.9,15–17,19,21

Given that the exchange of sex is often part of a personal economic strategy for at-risk women, interventions focused on reducing or removing the need for such exchange by assisting in personal economic development may contribute to reduced sexual risk-taking. For example, the need to depend on sex partners for income may be diminished, and time would be allocated to training or work rather than to risk activity. An intervention to directly increase access to financial resources among impoverished African American women in the South may operate on risk for disease in both direct and indirect ways—by including but also going beyond the stand-alone, small-group risk-reduction interventions that currently exist22–24 to target structural or contextual factors influencing risk. Such a multifaceted approach may be more effective than more traditional approaches to intervention.

MICROENTERPRISE AS HIV PREVENTION

Addressing structural factors represents the next level in HIV prevention intervention research.25,26 Microenterprise, which directly addresses individual and family poverty, is one potential intervention model for HIV/AIDS prevention. Various models of microenterprise exist in the field; however, we refer to microenterprise as encompassing a broad range of activities, including basic life-skills training, development of commercially viable products and services, access to markets, financial training, and financial support or microfinance of some type (e.g., credit, emergency loans, tax assistance).

The most well-known microenterprise project may be the Grameen Bank and the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC). The Grameen Bank, recipient of the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize, provides group-based credit for small business ventures primarily to poor women. The groups meet regularly, make regular deposits into a group savings account, and are responsible for ensuring that members make weekly repayments.27 The program provides training sessions for participants on setting and meeting objectives and conducting business operations. It is noteworthy that the Grameen program participants have been shown to have increased contraceptive use even though the program does not provide family planning services.28 In Africa and Asia, a variety of microfinance activities, based on a number of models including the Grameen model, have been shown to increase women's economic well-being, enhance contraceptive use, strengthen women's position in families, and improve the lives of youth in ways that are important to reducing susceptibility to HIV.27–31

Within the literature on microenterprise, there is a small but growing body of work on microenterprise and HIV/AIDS. For example, Pronyk et al.32,33 reported on a South African case study, Intervention with Microfinance for AIDS and Gender Equity (IMAGE), which integrated a curriculum that addresses gender and risk issues within an established Grameen-style group-lending microfinance program. While a number of challenges and issues emerged from the program (for example, how to establish effective partnerships between HIV and microfinance organizations), the study demonstrated a significant and positive relationship between an integrated package of HIV training and microcredit and HIV risk reduction.33 Pronyk et al. conclude that by mainstreaming HIV perspectives within microfinance organizations, the combined approach has the potential to address population-level vulnerability to HIV infection, particularly poverty and gender-based inequalities. A recent study in the Dominican Republic by Ashburn and colleagues34 determined that, among women who participated in a microlending program, control of “own money” was significantly and positively related to improved negotiation of safer sex, which points to a component of women's economic empowerment that may be critical for microenterprise-based HIV prevention efforts.

These promising international programs have led us to consider microenterprise as an HIV/AIDS prevention model among impoverished African American women in the southern U.S. However, given the context of the U.S. economy, legal system, and cultural differences, it is important to understand how to make such an intervention work in the United States and, in particular, for women at risk for HIV/STI infection in the American South. Preliminary evidence indicates that microenterprise interventions can reduce sexual risk behavior in the U.S. Sherman et al.35 conducted a pilot intervention in which drug-using and sex-trading women in Baltimore were taught HIV prevention risk reduction combined with the making, marketing, and selling of jewelry in six two-hour sessions. In a pretest/posttest design, women receiving this intervention reduced their drug use and number of sexual contacts and increased their condom use with sex trade partners. Notably, reductions in the number of sex trade partners were significantly predicted by the amount of money made from the jewelry sales. Although future studies would be strengthened with a more rigorous (e.g., randomized controlled) design, the findings are encouraging as a microenterprise model for HIV/AIDS prevention in the U.S.

PURPOSE OF THE CONSULTATION

On March 8–9, 2006, CDC, with the support and participation of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), convened a consultation meeting with experts in the fields of microenterprise development, HIV/AIDS prevention, and socioeconomic research on African American women in the southern U.S. We purposefully invited microenterprise experts working in U.S. settings because international microenterprise experiences may not directly apply given differences in the economy, legal system, and culture. The invited attendees included researchers, U.S.-based microenterprise program practitioners (some of whom have international experience), representatives of health departments and community-based organizations in the southern U.S., and organizations that provide funding for microenterprise activities. The purpose of the meeting was to garner the most up-to-date and relevant information on microenterprise projects that could be applied to conditions in the U.S. and to HIV/AIDS- and STI-related risk reduction.

REVIEW OF CONSULTATION

The agenda was structured around three principal questions: (1) What are the core elements of successful microenterprise programs?, (2) How are these best adapted to suit the needs of impoverished African American women in the southern U.S.?, and (3) What steps should be taken to prepare a microenterprise-based HIV prevention intervention for that population? For each question, the discussion was rich with information, experience, innovative ideas, and excitement regarding the notion that socioeconomic factors related to risk were on CDC's agenda.

Core elements of successful programs

Although it was not the purpose of the meeting to become expert in microenterprise, it was important to educate participants not familiar with microenterprise about fundamental aspects of the industry—basic models and their variations, theoretical backgrounds, populations served, specific program components, and limitations of microenterprise programs—to gauge what a successful program might look like and how to go about project development. At the same time, while the consultation could not cover all aspects and varieties of models that have been successful in a number of ways, participants were nevertheless provided an overview of programmatic elements. Note that a more comprehensive review of best practices in microenterprise programs in the U.S. can be found in Salzman et al.36

Specific microenterprise models and theoretical background

The three most common models include:

(1) Credit-led programs: small loans (microfinance or microcredit) are provided to startup businesses.

(2) Training-led programs: emphasize the development of skills and behaviors that accompany successful business practice; 85% of microenterprise programs are training-led. Note that the most successful programs offer at least business training in addition to access to credit.

(3) Combined microenterprise with wellness programs (e.g., Center for Black Women's Wellness in Atlanta): conduct health education and provide heath care or linkages to health care in addition to more traditional microenterprise services to small-scale, startup businesses.

Additionally, Individual Development Accounts (IDAs) can be included in microenterprise program models. This type of activity, which encourages the very poor to save money, is supported by research indicating that (1) saving is not unusual among the poor, whose means and manner of saving may differ from more widely recognized means such as bank accounts or investments, and (2) saving money, even a relatively small sum, can result in a more positive orientation to or outlook on the future and a stronger sense of control over one's life.37

The theories underlying most microenterprise program models include:

(1) Income theory: where microenterprise is expected to result in an improved standard of living.37

(2) Diversification theory: where microenterprise is expected to add another income stream to the household “portfolio.”38,39

(3) Compensating differential theory: where microenterprise is expected to provide non-monetary value, such as an improved outlook on life as a result of savings or ability to pay bills.40,41

(4) Social network theory: the economic activity resulting from microenterprise is expected to develop social capital and access to resources, which further strengthens economic activity.42

Populations typically served by microenterprise programs

Edgcomb and Klein43 report that 65% of microenterprise clients are women, 55% are minorities, and 59% had incomes at or below 80% of area median incomes. Due primarily to the concern for successful outcomes and other funding requirements, many microenterprise programs “screen for success.” That is, client eligibility is often based upon criteria, such as strong literacy skills, that would exclude many of the women of particular interest to those in public health: women faced with increased risk for disease, including HIV infection, due to the conditions imposed by often generations of living in poverty.

Across microenterprise programs, program clients express a range of goals, including gaining either supplemental or full-time income; having flexibility in work schedules to address, for example, child care needs; having more control and autonomy over their lives; avoiding discrimination and marginalization; and building personal or community assets.

For many programs, an ideal microenterprise client may be a woman who already runs a small bakery operation out of her home, and who, due to demand, has decided to add a helper and increase her products to sell to a larger number of customers. This woman's goal may be opening her own bakery shop within a few years. The ideal client for many microenterprise agencies comes to the program with at least a minimum level of entrepreneurial experience and aspirations.

Specific features and components of microenterprise programs

Participants agreed on the following as more typical components of microenterprise programs:

Microenterprise programs require transparency about expectations and outcomes; clients need to know what is expected of them in training programs and what their eventual success may look like. Goals are specified by clients (for example, “additional income to cover the rent” or “to support my daughter in college”) and are measured primarily in income gains.

These programs often directly address the barriers or challenges faced by clients and include business training, mentoring, coaching, access to capital, and access to markets. Some programs also incorporate training and skills development in areas needed to be able to function in a job or business, attending to basic job skills, or personal development and empowerment. In fact, consultation participants stressed the more lasting benefits of programs that help women develop self-reliance and self-esteem, with a resulting change in perspective about life's future prospects and possibilities. Participants from the field of HIV prevention described a similar experience, citing more success with interventions that provide skills building and promote self-esteem and personal empowerment.

The level of structured activities in microenterprise client training services varies, but structure is critical to help clients meet objectives. Providing an example of a highly structured training curriculum, the Women Entrepreneurs of Baltimore program includes three months of business skills training that requires 99 classroom hours and homework, a strict attendance policy, and sliding-scale fee requiring payment for participation in the program. At the other end of the structured programs scale are programs that provide only loan-qualifying and management services and refer clients to appropriate training programs.

Programs often provide funding mechanisms for clients. Loans are often made to individuals or cooperatives (groups of people collaborating in a business enterprise) with good business plans; the repay rate is high, though this sometimes depletes other family resources.

In addition to training on personal and business-skills development, many programs also have one-on-one technical assistance during the early life of the business.

Some programs take advantage of community resources to improve their clients' chances for success. For example, clients may be encouraged to participate in literacy programs when low literacy would hamper their ability to participate in microfinance trainings.

Some microenterprise programs offer support for joint ventures and cooperatives (i.e., daycare, event planning/catering, knitting co-ops) in addition to support for individual business development. Co-ops are more successful in rural areas or, in urban areas, in industries such as daycare. In fact, interest in the latter is so high that there are curricula available for daycare co-ops through the Association for Enterprise Opportunity, the umbrella organization for microfinance and microenterprise agencies in the U.S. Note that collaborative enterprises and cooperatives require more overhead and more training than individual businesses; another layer of skills and understanding is needed regarding functioning of co-ops and collaborative ventures.

In a typical microenterprise program that leverages resources by utilizing other community resources to help meet client needs (i.e., literacy or transportation), annual costs average about $2,500 per person served.

Finally, there are microenterprise programs that have integrated health education components into training. For example, some international models of microenterprise include education on health issues in their programs and assessment of health-related program outcomes. These programs tend to focus on maternal and child health, reproductive health, and nutrition. In the U.S., the Center for Black Women's Wellness in Georgia has separate program tracks for economic self-sufficiency and wellness, the latter involving education, referrals, and a part-time clinic covering reproductive and general health assessments, laboratory work, risk assessment and counseling, nutrition and exercise counseling, and a drug dependency program. However, such combination programs are not the norm for U.S. models of microenterprise.

Impact and limitations of microenterprise approaches

It has been difficult to determine how much individual household income is augmented by microenterprise activities. Individuals often will use other resources to aid their business enterprise, thus reducing the net flow to the household. Household incomes vary by family or household employment patterns and benefits, in addition to microenterprise activity. Some individuals/families have reported losing income as a result of participation in microenterprise activities; however, within this group, there are some who prefer microenterprise to being low-wage employees.

In the policy arena, while there tends to be general support for small business development, there is a lack of support for policies that would provide the same incentives to the working poor that those in better jobs typically receive. These would include matched retirement accounts, subsidies for child care and health care, and transportation assistance.

Other limitations that may be faced by microenterprise programs and clients include scarce individual and community resources; insufficient numbers of potential customers or clients for a developing microeconomic activity; and lack of economic and social networks and services to support new microeconomic activity. In some communities, women do not have control over resources or assets, and their own economic and personal development could be put at risk by other relationships, such as partner control over assets. Many of these factors point to structural limits on poverty alleviation. However, as more than one participant indicated, “Almost any level of improvement in income for a woman in real poverty is important to that woman in tangible ways.”

Health issues are critical considerations in microenterprise program development and implementation because most microenterprises cannot afford health insurance. Therefore, while microenterprise may address some areas of financial and other personal need, microenterprise programs focused on increasing incomes alone are unlikely to solve the need for health insurance that characterizes the poor in the U.S. today. However, microenterprise agencies may be well-positioned to develop community collaborations in which resources may be pooled to improve insurance purchasing power.

How can microenterprise programs best be adapted to suit the needs of impoverished African American women in the southern U.S.?

Programs that seek to address the challenges faced by women in poverty should emphasize life-skills training prior to training in financial and employment matters. Life skills may include literacy, short- and long-term planning, and working with others such as colleagues, clients, employers, and employees. It is also important for women to learn how to control their assets in such a way that their lives are improved. Such programs should also link clients to community resources that can assist them with lack of transportation, limited or no access to child care, medical care, and other personal services.

Programmatically, short-term, small, step-by-step objectives are more realistic to achieve than aiming all at once on longer-term goals in the course of a training program. This graded mastery approach builds in a good chance of frequent successes, which are important to both skills development and motivation. Additionally, program developers should understand that many poor women are natural entrepreneurs, making a living or making do in very creative ways—doing hair or nails or weaving baskets—and microenterprise programs should acknowledge and build on the skills and perspectives that these women have already developed.

What should be done to prepare a microenterprise-based HIV prevention intervention for African American women in the southern U.S. who are at risk for transmission due to poverty?

Our participants, coming from very different backgrounds and areas of expertise, nevertheless came to strong and enthusiastic agreement on the priorities and parameters for microenterprise programs designed to reduce risk for disease. Recommendations were based on a comprehensive approach to development of such programs. Program components should be clearly articulated, as described by the following program planning questions.

How will the program (including program monitoring and staffing) be developed and who will do so?

Who are the partners and what are their roles?

What activities, services, and program development issues are critical?

How will HIV prevention and other health issues be integrated?

What are the program implications for policy development and sustainable impact?

By the end of the consultation, there were five general domains of agreement on priority considerations for program planning, development, and implementation, which corresponded to the questions.

Program development and goal-setting

As a general principle, program development and goal-setting should be defined by the community.

A microenterprise-based HIV prevention intervention should be owned by the community. Therefore, the community should be involved in the design; there should be evidence of community buy-in. Families should be included in design and planning; individual women are going to be empowered, but families of those women should be included in the planning and support of the activities. Further, the target population, together with other local key stakeholders, should define the community that would be involved in program development.

Core economic goals should be locally defined by program clients and community partners, with the assistance of a microenterprise agency, rather than being determined by funders, given differing economic and social parameters across communities.

Likewise, the target population, with training and guidance provided by microenterprise agencies and informed by community input, should select the types of business or economic activities for which they would receive training and support.

Many participants recommended a case-management model, in which programmatic goal-setting begins where clients are and provides a program that fits the client/local community needs and resources.

Finally, participants agreed that to reduce HIV/AIDS risk among women in the South, it will be important to focus, though perhaps not exclusively, on rural areas.

Partnerships and roles

In addition to community-based program development, activities should be based on a broad array of partnerships to achieve microenterprise and HIV risk-reduction goals.

A microenterprise program designed to impact the lives of African American women in poverty in the South needs to be multisectoral both in funding and on the ground. Participants felt strongly that, particularly for women in rural areas, disciplinary or sector diversity (e.g., health, community development, labor, agriculture, transportation, housing, and microenterprise) would be key to helping women overcome the challenges of rural poverty. The model for this may be the community planning process that has been established for local decision-making about HIV prevention program priorities. Funding for microenterprise projects should require this type of community collaboration, with each collaborator bringing its particular programmatic expertise into the mix.

The partnership should involve microenterprise agencies that offer a range of services to meet a host of client needs, including literacy training and basic job skills in addition to the development of economic literacy and business skills. These agencies know the field of microenterprise; some know how to work with the target population (unemployed/underemployed poor African American women in the South). However, links to available community resources (e.g., for literacy training or mentoring) may also be critical parts of microenterprise programs and contribute to the development of community support for those programs.

Partners should also include local and state health departments, especially regarding the prevention components of a microenterprise-based HIV/STI prevention program. These agencies are familiar with local HIV/STI-related challenges, appropriate interventions, and evaluations, and typically have experience reaching the target population.

In addition to more typical partnerships, development of communication and interaction utilizing new technologies should be explored. For example, the Internet offers expanded potential for marketing and further development of microenterprise business opportunities.

A variety of local and national partners would expand the efficacy and sustainability of a microenterprise activity with regard to both economic and health outcomes. Local partners could include community stakeholders in the development of a new economic activity; national partners may include foundations and other funders or programs in the areas of economic development, rural development, community development, and women's health. For example, the National Association of City and County Health Officials (NACCHO) has created a planning intervention called Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP), which is a community-wide strategic planning and implementation tool for improving community health that might be utilized or incorporated for microfinance interventions (see http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/MAPP.cfm).

Within any partnership arrangement, it is critical that poor women be the principal partners and should be intimately involved in the project from the ground up. Women are change agents by virtue of their social roles and perspectives, their patterns of networking and support, and their influence on families and communities. And while the program should focus on African American women, other poor women or men should not be excluded, given the extent of economic need and sensitivities that might exist in local communities. Certainly, programs that focus on men in poverty should also be considered. Additionally, as has been explored internationally, the microenterprise approach to HIV prevention should include both HIV-positive and HIV-negative people to support both prevention of acquisition and improve quality of life for those who are living with HIV.

Community partnerships are essential to successful microenterprise programs, but community partners also need some incentive; for example, a community agency may benefit from claiming status as a minority business and being able to count the microenterprise project participants as part of their own participant base.

Critical program development issues and critical program activities and services

The goal of microenterprise planning and program development should be to provide models and develop programs that can lead to sustainable economic gains.

- Models to consider:

- — In addition to support for individual business development, the collective or cooperative approach to business development is particularly appropriate for many rural areas.

- — An employee-owned business model may also be part of a design.

- — Partnering with existing businesses (farms, factories, service industries) to hire women might be more realistic in some areas than development of new economic activity.

- — Include savings accounts of some type, either in banks or health savings accounts in clinics, to provide asset building.

- — Include training in finance/economic skills as well as other skills needed for success; use a graded mastery approach.

- — In areas where jobs are few and markets are saturated, program planners should consider development of new economic activity—services or businesses new to the community—which would open up new markets.

Programs, especially rural programs, where needs such as transportation would be different from urban areas, might make use of new technologies for communication or new methods for sharing information/training, such as the circuit rider approach, in which trainings and other services are delivered to different areas at different times.

- An important consideration for project development and implementation is timing. Given that some funders such as CDC now limit intervention research to two to three years, consultation participants stressed the importance of changing this policy to provide time to develop partnerships in addition to program implementation and evaluation. Therefore:

- — Program/partnership development on the local level for support of a project to introduce new economic activity into a community may take up to two years. This would include a planning stage, formative work on community economic needs, economic infrastructure, and the development of key relationships.

- — In addition to a program development period, a three- to four-year implementation time frame will allow for measurable results; note that, while noneconomic benefits are seen early on in microenterprise programs, economic benefits often do not materialize as quickly.

Evaluation activities should include qualitative and quantitative assessments, and the project should make efforts to assure that infrastructure and skills used to develop and evaluate microenterprise activities for HIV prevention be sustained within the target communities once the project is over. Academic institutions, especially local colleges, can provide a range of needed skills and services in this domain of activity.

Outcome measures should include community, family, and individual outcomes, as well as an array of optional health measures from which program planners may choose. Participants emphasized the importance of outcomes related to mental health, substance abuse, health promotion and care practices, domestic violence, obesity, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease in addition to sexual risk reduction. Surrogate indicators should be used as markers for more long-term outcomes; for example, risk behavior or STIs as proximate indicators of HIV disease incidence, school performance as a measure of family wellness, or environmental measures such as structural improvements to homes as a measure of community wellness.

Integrating health issues with microenterprise activities

Reiterating the collaborative theme, integrating HIV prevention should be guided by local partnerships and previous experience rather than by federally mandated priorities alone.

Identifying ways to integrate HIV prevention content in research on efficacy of microenterprise as HIV prevention would be a project design issue; for example, one could compare microenterprise programs with and without a formally integrated HIV/AIDS prevention component, or HIV prevention programs with and without a microenterprise component. Such comparisons could assess the independent impact of economic improvement on HIV prevention.

Continue learning from other microenterprise work and previous studies to become familiar with microenterprise possibilities for women in poverty and the potential influence of those programs on women and communities. Good examples of relevant research would be international microenterprise programs and the Welfare to Work Program research on family and community outcomes.

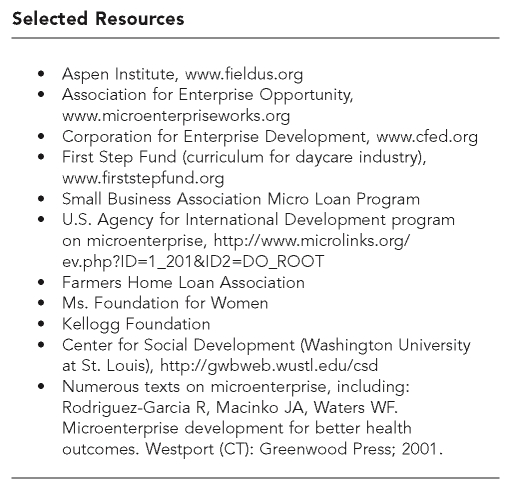

Finally, participants pointed to the many resources (programs, curricula, other materials) developed in the microenterprise field in the last 10 years, which should be utilized by HIV prevention program planners.

Implications for future programs and for policy

Demonstration projects typically look at outcomes that approximate general public health goals. For example, a project that would evaluate microenterprise as HIV prevention would assess reductions in HIV-related risk behavior rather than incidence of HIV infection among participants. However, if improved public health outcomes may be linked to economic development, then long-range planning should include assessment of public health impact, such as HIV/STI incidence rates, in addition to a variety of measures of economic improvement, such as policies that support economic development in poverty-stricken areas and specific domains of community well-being.

Additionally, national-level policy can be influenced by local experience; for example, health departments have a role through their national-level organizations in helping to determine best practices for national-level policy. The implication here is that a successful multisectoral collaboration linking microenterprise and prevention of HIV and STIs could impact national practice.

SUMMARY OF KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE CONSULTATION

Participants were unanimously enthusiastic about CDC's willingness to address an important contextual factor (poverty and its effects on individuals, families, and communities) in HIV prevention.

Participants from the microenterprise field stressed that the successful models for low-income women are those that incorporate life-skills training in addition to providing financial training and resources. Many of these participants also indicated that life-skills training is more essential and more long-lasting than financial resource packages for many women, and the noneconomic benefits—such as self-reliance, self-esteem, and optimism about the future—are important outcomes associated with microenterprise training and activities. This was echoed by individuals with experience in HIV prevention programs, who indicated that development of life skills is often critical to the success of HIV prevention activities.

There are a variety of microenterprise models that would be suitable for consideration as HIV prevention intervention. Some participants stressed that individual development accounts (IDAs) have the advantage of providing a vision for the future that other microenterprise models do not. The notion of a microenterprise model should be fluid, recognizing that combinations of approaches may be appropriate (e.g., combining IDAs with microenterprise training).

Many participants emphasized the importance of community input into design and evaluation of microenterprise-based prevention interventions, stressing that federally mandated intervention designs would not be appropriate given the need for programs to fit local conditions.

Microenterprise activity in poor communities should address the economic organization within those communities by including local and national stakeholders in economic development. This is one of the important ways to assure sustainable development, particularly among poor and underserved populations. As one participant noted, “‘Healthy communities’ is a multifactoral concept—you need transportation and you need good housing.”

There was general agreement that funding should flow into the community and to health departments and microenterprise agencies for collaboration among at least these two types of agencies on an intervention.

Some participants (especially those with microenterprise experience) were cautious about intervention design, noting that some aspects of microenterprise interventions may leave a small minority of participants in worse shape economically (by using family resources to support the business) and at risk for economic predation by partners, friends, or others.

Finally, the conceptualization of HIV prevention was significantly broadened to include contextual factors (e.g., stable and safe housing and neighborhoods, access to resources including health care) that increase or decrease health risks. For most of these factors, poverty was understood by the consultation participants as being a critical underlying component. Therefore, addressing economic stressors using microenterprise was understood to be an important strategy for improving health in general as well as an important approach to HIV prevention.

FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

As an HIV prevention intervention, microenterprise differs from previously developed interventions in important ways. First, it has the capacity to disentangle the nexus of risk that characterizes the lives of those at risk for HIV or living with HIV.25 Poverty (and racism, arguably its most significant determinant) is associated with numerous factors throughout the life course that lead almost inexorably to risk for HIV infection.6,44 That is, individuals at risk for HIV often have histories of trauma, drug abuse, incarceration, unemployment, poor education, and homelessness, all of which have the potential to be alleviated, at least in part, by economic empowerment programs.

Beyond this, microenterprise has the ability to affect numerous health conditions in addition to HIV risk. Poverty is implicated in most health problems, and poverty- and race-related health disparities are viewed by many as the preeminent health issue—in fact, social justice issue—currently confronting U.S. society.45–47 Accordingly, economic empowerment may be able to reduce hypertension and other cardiovascular health problems, the incidence and course of numerous cancers, violence, substance abuse, and many other negative health conditions. Economic empowerment may achieve this through behavioral and lifestyle changes, increasing health-care utilization, and also through the alleviation of poverty-induced stress and its numerous health-related manifestations.48 For example, CDC's Hope Works project, an intervention that includes assistance with developing economic objectives, targets weight management and stress reduction in addition to job-skills training and improving incomes.49 The ability to affect multiple health outcomes is promising not only for economic empowerment, but also for other structural and community-level interventions such as incarceration policy50 and community mobilization.51,52

Thus, the ongoing development of structural and community interventions, involving public and private partnerships at different intervention levels, has the potential to be cost-effective relative to single-disease interventions by simultaneously affecting many health outcomes. For example, a single structural or community intervention could be evaluated for its effects on numerous health processes and conditions, ideally with funding coming from each of the relevant components of the Public Health Service, making even the research cost-effective. In the long term, this would implicate a paradigm shift in funding practices and in public health intervention research, program development, and funding approaches.

In the meantime, small steps can be exciting: increased multisectoral collaboration on structural interventions among scientists and practitioners, whose formal missions are otherwise or typically disease- or sector-specific, has the potential to address important social and economic factors that have a significant impact on public health.

Selected Resources

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their appreciation to the participants in the consultation described in this article. It was a truly exciting and energizing event, and the authors fervently hope that it will bear rich fruit. By its closure, the consultation felt more like the beginning of a team effort rather than a one-off meeting.

A special appreciation goes to Christopher Bates, both a consultation participant and the sponsor of this project through the auspices of his office as Acting Director of the Office of AIDS Policy at the Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

This project was funded by the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of AIDS Policy.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.McKinnon J. The black population in the United States: March 2002. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau; 2003. Current Population Reports, Series P20-541; [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States, by race/ethnicity, 2000–2004. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2006;12:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDavid K, Li J, Lee LM. Racial and ethnic disparities in HIV diagnoses for women in the United States. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2006;42:101–7. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000199353.11479.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farley TA. Sexually transmitted diseases in the Southeastern United States: location, race, and social context. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(7 Suppl):S58–64. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175378.20009.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Lee CH U.S. Census Bureau, editors. Current population reports. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2006. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2005; pp. 60–231. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishaw A U.S. Census Bureau, editor. Census 2000 special reports. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005. Areas with concentrated poverty: 1999; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu KT. State-level variations in income-related inequality in health and health achievement in the US. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:457–64. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reif S, Golin CE, Smith SR. Barriers to accessing HIV/AIDS care in North Carolina: rural and urban differences. AIDS Care. 2005;17:558–65. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331319750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Coyne-Beasley T, Doherty I, Stancil TR, et al. Heterosexually transmitted HIV infection among African Americans in North Carolina. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2006;41:616–23. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191382.62070.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzpatrick L, Forna F, Greenberg A, Leone P, Adimora A, Foust E. HIV infection among young black women. The evolving epidemic: risk behavior, incidence, and prevalence. the 12th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2005 Feb 22–25; Boston. Presented at. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein C, Easton D, Parker R. Structural barriers and facilitators in HIV prevention: a review of international research. In: O'Leary A, editor. Beyond condoms: alternative approaches to HIV prevention. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Pub; 2002. pp. 17–46. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krieger N, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV. Monitoring socioeconomic inequalities in sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and violence: geocoding and choice of area-based socioeconomic measures—the public health disparities geocoding project (US) Public Health Rep. 2003;118:240–60. doi: 10.1093/phr/118.3.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagry-Agren S. Infectious diseases and women's health: link to social and economic development. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2001;56:92–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in the rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S115–22. doi: 10.1086/425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellerbrock TV, Chamblee S, Bush TJ, Johnson JW, Marsh BJ, Lowell P, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection in a rural community in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:582–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez J, Comerford M, Chitwood DD, Fernandez MI, McCoy CB. High risk sexual behaviors among heroin sniffers who have no history of injection drug use: implications for HIV risk reduction. AIDS Care. 2002;14:391–8. doi: 10.1080/09540120220123793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baseman J, Ross M, Williams M. Sale of sex for drugs and drugs for sex: an economic context of sexual risk behavior for STDs. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:444–9. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199909000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gentry QM, Elifson K, Sterk C. Aiming for more relevant HIV risk reduction: a black feminist perspective for enhancing HIV intervention for low-income African American women. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17:238–52. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.4.238.66531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stratford D, Ellerbrock TV, Chamblee S. Social organization of sexual-economic networks and the persistence of HIV in a rural area in the USA. Cult Health Sex. 2007;9:121–35. doi: 10.1080/13691050600976650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wambach KG, Byers JB, Harrison DF, Levine P, Imershein AW, Quadagno DM, et al. Substance use among women at risk for HIV infection. J Drug Educ. 1992;22:131–46. doi: 10.2190/36BW-GNR7-Y55K-2JMJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campsmith ML, Nakashima AK, Jones JL. Association between crack cocaine use and high-risk sexual behaviors after HIV diagnosis. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2000;25:192–8. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200010010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shain RN, Piper JM, Newton ER, Perdue ST, Ramos R, Champion JD, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a behavioral intervention to prevent sexually transmitted disease among minority women. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:93–100. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Partner influences and gender-related factors associated with noncondom use among young adult African American women. Am J Community Psychol. 1998;26:29–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1021830023545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Leary A. Women at risk for HIV from a primary partner: balancing risk and intimacy. Ann Rev Sex Res. 2000;11:191–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Leary A. Substance use and HIV: disentangling the nexus of risk. Introduction. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sumartojo E. Structural factors in HIV prevention: concepts, examples, and implications for research. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S3–S10. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuler SR, Hashemi SM. Credit programs, women's empowerment, and contraceptive use in rural Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plann. 1994;25:65–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuler SR, Hashemi SM, Riley A. The influence of women's changing roles and status in Bangladesh's fertility transition: evidence from a study of credit programs and contraceptive use. World Development. 1997;25:563–75. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waters WF, Rodriguez-Garcia R, Macinko JA. Westport (CT): Greenwood Press; 2001. Microenterprise development for better health outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hashemi SM, Schuler SR, Riley AP. Rural credit programs and women's empowerment in Bangladesh. World Development. 1996;24:635–53. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boungou Bazika JC. Effectiveness of small scale income generating activities in reducing risk of HIV in youth in the Republic of Congo. AIDS Care. 2007;19(Suppl 1):S23–4. doi: 10.1080/09540120601114444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pronyk PM, Kim JC, Hargreaves JR, Makhubele MB, Morison LA, Watts C, et al. Microfinance and HIV prevention—emerging lessons from rural South Africa. Small Enterprise Development. 2005;16:26–38. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, Morison LA, Phetla G, Watts C, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: results of a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1973–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashburn K, Kerrigan D, Sweat M. Micro-credit, women's groups, control of own money: HIV-related negotiation among partnered Dominican women. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9263-2. AIDS Behav 2007 Jun 30. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherman SG, German D, Cheng Y, Marks M, Bailey-Kloche M. The evaluation of the JEWEL project: an innovative economic enhancement and HIV prevention intervention study targeting drug using women involved in prostitution. AIDS Care. 2006;18:1–11. doi: 10.1080/09540120500101625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salzman H, McKernan S-M, Pindus N, Castañeda RM. Capital access for women: profile and analysis of U.S. best practice programs [monograph on the Internet] The Urban Institute. 2006. Jul, [cited 2007 Jun 26]. Available from: URL: http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/1001061_Capital_Access.pdf.

- 37.Sherraden MS, Sanders CK, Sherraden MW. Kitchen capitalism: microenterprise in low-income households. New York: State University of New York Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen MA, Dunn E. Household economic portfolios. Microenterprise Impact Project (MIP) Washington: USAID Office of Microenterprise Development; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edin K, Lein L. Making ends meet: how single mothers survive welfare and low-wage work. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blau FD, Ferber MA, Winkler AE. The economics of women, men, and work. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenstein C, Light I. Race, ethnicity and entrepreneurship in urban America. New York: Aldine Transaction; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waldinger R. Through the eye of the needle: immigrants and enterprise in New York's garment trades. New York: New York University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edgcomb EL, Klein JA. Opening opportunities, building ownership: fulfilling the promise of microenterprise in the United States. Washington: Aspen Institute FIELD program; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Leary A, Martins P. Structural factors affecting women's HIV risk: a life-course example. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S68–S72. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:167–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shavers VL, Shavers BS. Racism and health inequity among Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:386–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamin AE. The right to health under international law and its relevance to the United States. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1156–61. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adler NE, Snibbe AC. The role of psychosocial processes in explaining the gradient between socioeconomic status and health. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:119–23. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bowen R, Peterson P. Following the leader: process evaluation of community health workers in an obesity intervention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2006 National Health Promotion Conference; 2006 Sep 12–14;; Atlanta. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gaiter JL, Potter RH, O'Leary A. Disproportionate rates of incarceration contribute to health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1148–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.086561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wandersman A. Community mobilization for prevention and health promotion can work. In: Schneiderman N, Speers MA, Silvia JM, Tomes H, Gentry JH, editors. Integrating behavioral and social sciences with public health. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2000. pp. 231–47. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stratford D, Chamblee S, Ellerbrock TV, Johnson RJ, Abbott D, Reyn CF, et al. Integration of a participatory research strategy into a rural health survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:586–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]