SYNOPSIS

It is well recognized that methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has become a community pathogen. Several key differences between community-associated and hospital-associated MRSA strains exist, including distinct methicillin resistance genes and genetic backgrounds and differing susceptibility to antibiotics. Recent studies have demonstrated that typical hospital and community strains easily move between hospital and community environments. Despite evidence of MRSA's expanding reach in the community, the best methods for population-level detection and containment have not been established.

In an effort to determine effective methods for monitoring the spread of MRSA, we reviewed the literature on hospital-associated and community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) in the community and proposed a model for enhanced surveillance. By linking epidemiologic and molecular techniques within a surveillance system that coordinates activities in the community and health-care setting, scientists and public health officials can begin to measure the true extent of CA-MRSA in communities and hospitals.

Until the early 1980s, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) remained an exclusively nosocomial pathogen.1 The more recent emergence and spread of MRSA outside of the hospital setting has caused alarm among public health officials and clinicians.2 Four disturbing trends indicate MRSA's growing reach: (1) the number of cases of MRSA inside and outside of the hospital is rising, (2) the distribution of S. aureus infections in the community is shifting from methicillin-sensitive to methicillin-resistant, (3) MRSA infections have caused significant morbidity in healthy individuals, and (4) the boundary between the hospital and the community has blurred. Without proper detection and control, the problem of community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) will likely worsen.

CA-MRSA has been associated with high morbidity and hospitalization; in rare cases, severe CA-MRSA infections have even caused death. In the late 1990s, an outbreak of MRSA caused the deaths of four children in the Midwest.3 More recently, in January 2007, six previously healthy adults and children died of CA-MRSA pneumonia.4 Other communities have reported dramatic increases in the incidence of CA-MRSA infections.3 Outbreaks of CA-MRSA causing both mild skin infections and fatal necrotizing pneumonia have occurred in diverse populations in the U.S., such as Native Americans, homeless youth, men who have sex with men (MSM), jail and prison inmates, military recruits, athletes, and children in day care centers. In several communities across the U.S., CA-MRSA has become the predominant pathogen isolated from skin infections, especially among children.3

For much of the past two decades, experts debated the origins of CA-MRSA. Initial reports of MRSA in the community revealed that most community-associated infections were probably acquired in the health-care setting. The majority of patients with MRSA had either direct or indirect contact with the health-care setting, suggesting that their infections resulted from hospital strains that were carried into the community.5 Some strains isolated from patients in the community even shared identical resistance patterns with common nosocomial strains.6 Due to the observed similarities between cases with community-associated infection and cases with nosocomial infection and the high prevalence of recent health-care exposure, many believed that community strains were related to endemic hospital strains.

Remarkably, in the last several years, CA-MRSA has been reported in healthy individuals with neither direct nor indirect contact with the health-care system.3 Molecular analysis reveals that community isolates from patients without health-care exposures are genetically distinct from nosocomial isolates. Moreover, the majority of CA-MRSA strains possess novel virulence and resistance traits rarely observed in nosocomial strains.5 Molecular analysis has also allowed researchers to detect the circulation of typical community and hospital strains between settings. Several outbreaks caused by typical community strains have occurred in the postpartum and neonatal hospital wards in major cities.7–9 Other studies have documented a relatively high prevalence of nosocomial strains in communities such as Atlanta.10,11 Together, these findings indicate that CA-MRSA results from both the introduction of nosocomial strains into the community and the de novo emergence of novel strains of pathogenic MRSA. In turn, community strains have entered the hospital setting, further expanding the reservoir.

Data on the epidemiologic and biological dimensions of CA-MRSA demonstrate the changing epidemiology of a common and virulent pathogen.3,7–13 With the boundary between community and nosocomial settings clearly porous, it is essential that surveillance systems cover both settings. However, such systems have been implemented sporadically. Hospital centers in major cities such as Houston have conducted multiyear surveillance projects for CA-MRSA strains.14 However, community control of MRSA has largely been limited to outbreaks.15–17 In addition, molecular genotyping has been a central tool for describing the origins and epidemiology of MRSA; molecular analysis must be used to detect and control the circulation of MRSA strains between the hospital and community. By linking epidemiologic and molecular techniques within a surveillance system that coordinates activities in the community and health-care setting, we can begin to define and measure the true extent of MRSA in the community and the hospital.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE ON CA-MRSA IN THE COMMUNITY AND HOSPITAL

Traditionally, studies have distinguished between hospital-acquired MRSA (HA-MRSA) and CA-MRSA by using temporal and clinical criteria, such as the timing and location of diagnosis (HA-MRSA are identified 48 to 72 hours after admission and CA-MRSA are identified in the community or within 48 to 72 hours of hospital admission) and the presence or absence of health-care risk factors, such as hospitalization, indwelling catheterization, and dialysis. Researchers have recently detected MRSA in previously healthy individuals who lack these risk factors; and MRSA strains typically seen in community settings now appear to spread nosocomially.

There are several key differences between typical community and nosocomial strains of MRSA. These differences might explain the proliferation and spread of certain MRSA strains in the community.

The methicillin resistance determinant: SCCmec type IV

The majority of methicillin-resistant strains in the community seem to contain a specific type of mobile genomic island (i.e., genetic element that has integrated into the organism's genome), the staphylococcal chromosome cassette mec (SCCmec) type IV element. This 21- to 24-kilobase stretch of DNA carries the methicillin resistance determinant mec and two recombinase genes that guide excision and integration of the SCCmec element. Therefore, the type IV element is considerably smaller in size than other SCCmec types.18 The antibiotic resistance gene, mecA, confers resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics including cephalosporins. The type IV genotype is consistent with the phenotypic susceptibility to multiple antibiotic classes frequently described among community isolates of MRSA from patients without health-care risk factors.5,19

Several studies have found a high prevalence of the SCCmec IV element among CA-MRSA strains isolated from patients without health-care risk factors.20–23 One study determined that CA-MRSA isolates were six times more likely to possess the SCCmec IV element than HA-MRSA isolates.21 Okuma et al. found that no CA-MRSA strains carried the type I–III elements; conversely, Vandenesch et al. found that no HA-MRSA strains contained the type IV element.22,23 Studies have suggested that the small size of the type IV element has little cost for the fitness of community strains; by comparison, the larger elements (type II and III) typically carried by nosocomial strains have extra resistance determinants and other genes.3 It is possible that the larger size of type II and III elements creates too great a cost for HA-MRSA strains to compete in the community.

Multiple susceptibility, tissue tropism, and virulence traits

Studies comparing cases of HA-MRSA vs. cases of CA-MRSA without health-care risk factors have found that CA-MRSA strains are more likely to be susceptible to multiple antibiotics and to cause skin and soft-tissue infections.1,21,24,25 Some suggest a role for the Panton-Valentine leukocidin or pvl genes (a toxin to human white blood cells) in causing necrosis, both in superficial skin infections and necrotizing pneumonia.20,26 Naimi et al. found that CA-MRSA isolates were also more likely to possess pvl genes than were HA-MRSA isolates.21 Likewise, studies have found that a high proportion of skin and soft-tissue infection isolates possess pvl genes.20,21 The dual presence of the type IV element and pvl genes, two genetic factors infrequently found in nosocomial strains, might represent “super-adaptation” that renders strains particularly suited for community spread.20,23,26–28

Certain CA-MRSA strains possess virulence traits that may aid survival and spread in the community, such as bacteriocin and arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME). Bacteriocin is a toxin to other bacteria closely related to the toxin-producing strain. ACME, exclusively found in the community clone, USA 400, is a mobile genetic element that likely enhances growth and survival within the host. The main enzyme, arginine deiminase, is an inhibitor of human peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferation, allowing for survival at low pH levels and aiding intracellular invasion.13

Genetic background

Numerous studies have found that the genetic background of community strains differs from that of nosocomial strains.1,21,23,27,29 For instance, the agr (accessory gene regulator) type 3 (agr3) background is more common among CA-MRSA than HA-MRSA isolates.21,23 The agr type 3 background corresponds to a major phylogenetic lineage for pathogenic S. aureus sensitive to methicillin (MSSA). The predominance of agr3 among CA-MRSA isolates suggests a common origin for pathogenic MSSA and CA-MRSA, which is consistent with findings from genetic analyses of virulent CA-MRSA and CA-MSSA within other studies.22,23,26,30,31

In addition, the prototype CA-MRSA strain, MW2, possesses heterogeneous subpopulations of resistance cells (i.e., some subpopulations of cells examined are resistant to methicillin, while others are not resistant). In contrast, Mu3, a representative hospital strain, possesses homogeneous methicillin resistance (i.e., all subpopulations of cells examined are resistant to methicillin). The heterogeneous methicillin resistance of MW2 could have arisen because antibiotic exposure did not place a strong selective pressure on CA-MRSA strains. Lack of antibiotic selective pressure is what would be expected if MW2 evolved outside of the hospital environment.22

CA- and HA-MRSA strains in the community

Based on the presumptive difference in origin of CA- and HA-MRSA strains, there are at least two different pathways to producing MRSA in the community. In the first, a community-resident MSSA strain that is unrelated to hospital strains acquires the type IV SCCmec element and becomes methicillin resistant. Why the CA-MRSA strains would develop methicillin resistance in the absence of a strong antibiotic selective pressure is difficult to explain. Salgado et al. noted that community strains of MRSA have longer colonizing times than typical hospital strains, with 36.9 billion annual person-days of S. aureus colonization in the community and 50.4 million person-days in the hospital: a 733-fold difference. Longer duration of colonization could allow for acquisition of the methicillin-resistant determinant even in the community.32

The genotype of the type IV element—mecA and the genes needed for its transfer—suggests that it has a single function: the transfer of the methicillin resistance determinant.33 In fact, the SCCmec IV is quite mobile: Robinson and Enright determined that approximately half of the acquisitions of the SCCmec over time involved an MSSA clone acquiring the type IV element. Strains with faster growth rates, greater colonization abilities, and limited antibiotic resistance may be better suited to survive and compete in the community.33 The type IV element may then be advantageous in an environment where antibiotic use is sporadic, such as that of the community, and its small size may exert little fitness cost on the strains that carry it.

In the second pathway, a hospital strain escapes and circulates in the community. Molecular analyses aimed at identifying well-characterized nosocomial strains have found a range in point prevalence of these strains in the community of 11% to 59%.10,11,34 However, transmission of endemic hospital strains does not seem to be sustained in community settings.35 Strains carrying SCCmec types II and III circulate at low prevalence in the community: one study found that 11.0% of strains circulating in the community carried non-type IV SCCmec elements, while another reported only 3.6%.11,12 A possible explanation for the low community prevalence of HA-MRSA containing SCCmec type II and III is that multidrug resistance might increase the cost on fitness.

Nosocomial transmission of CA-MRSA

How CA-MRSA strains might be transmitted in a hospital setting is a different question. Either or both of two different phenomena might be at work in this setting: First, rare multidrug-resistant community strains could enter from the community and then circulate in the hospital. The multidrug-resistant phenotype of these strains would aid in their survival and spread in the hospital setting: any strain with multiple resistances, regardless of its origin, would be selected and amplified in the hospital environment.32 Recent studies have already documented this phenomenon in San Francisco.12,36 Secondly, community strains with single methicillin resistance could potentially enter this setting and then acquire additional resistance genes within the medical-care environment.

CA-MRSA strains have caused outbreaks in neonatal and postpartum units of several U.S. hospitals.7–9 For instance, outbreaks in two different New York City hospitals in 2002 were caused by MRSA identical or similar to MW2, the prototypical community strain; all contained pvl genes and the type IV SCCmec element.7,8 In most cases in which community strains have been introduced into hospital settings, they have caused limited outbreaks. However, typical community strains have established themselves in at least one hospital setting where they now coexist with typical nosocomial strains. Carleton et al. determined that isolates belonging to clonal groups with the SCCmec IV accounted for much higher proportions of isolates from patients in that hospital than did isolates from clonal groups with type II and III elements in the community setting. The introduction of community strains in the hospital setting might indicate an expanding community reservoir.12

Interestingly, penetration of CA-MRSA strains into hospital settings might have decreased the prevalence of multiple resistant MRSA infections (i.e., resistant to two or more non-beta-lactam antibiotics). The diminution has been evident in U.S. intensive care units from 1992 to 2003 and in Europe. The decline seems to be related to the introduction of community strains that are typically susceptible to multiple non-beta-lactam antibiotics (i.e., CA-MRSA harboring the type IV SCCmec element and no other resistance determinants.37

Clearly, the supposed barrier between the hospital and the community is permeable. However, it is not equally permeable in both directions: while strains carrying the SCCmec IV seem to be able to enter and establish themselves in the hospital, strains with the type II and III elements are largely confined to the hospital setting. It is also plausible that both methicillin-sensitive and -resistant community strains could acquire additional resistance genes in the future and become established in the hospital setting. Reports of multidrug-resistant CA-MRSA strains have already emerged inside and outside of the U.S.12,36 While there is virtually no barrier in terms of strains entering either setting, strains carrying type IV continue to survive longer and proliferate better in the community setting, and strains carrying SCCmec II and III survive and proliferate better in the hospital setting.

PUBLIC HEALTH RESPONSE

Critical advances, such as molecular characterization of the SCCmec region, have allowed for a greater understanding of the origins and epidemiology of CA-MRSA. A few studies have begun to characterize the extent of the community reservoir and to determine the incidence of MRSA in the community. Graham et al. analyzed 2001–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data and found nasal carriage to be 0.8%.38 Using the same NHANES data, Kuehnert found that 2.4% of staphylococcal isolates contained pvl genes.39 Fridkin et al. used population-based surveillance data to determine the incidence of CA-MRSA in Baltimore and Atlanta. The annual disease incidence was 25.7 cases per 100,0000 in Atlanta and 18.0 cases per 100,000 in Baltimore.40 In light of the mounting evidence of an expanding reservoir for MRSA, public health officials must initiate broad-based methods for detection that will inform strategies to impede the spread of CA-MRSA.

Surveillance of MRSA—clinical and subclinical cases (i.e., presumed infections that have not been laboratory confirmed)—is the first step for detection. The aims of such a surveillance system are to quantify the number and distribution of CA-MRSA, determine susceptibility profiles, and examine determinants of community spread. National implementation of the surveillance system would be neither necessary nor particularly valuable. Individual states that have identified CA-MRSA as a large and growing problem could adopt the proposed surveillance model. Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness and efficiency of the state-based system could then guide decisions regarding the implementation of a national system in the future.

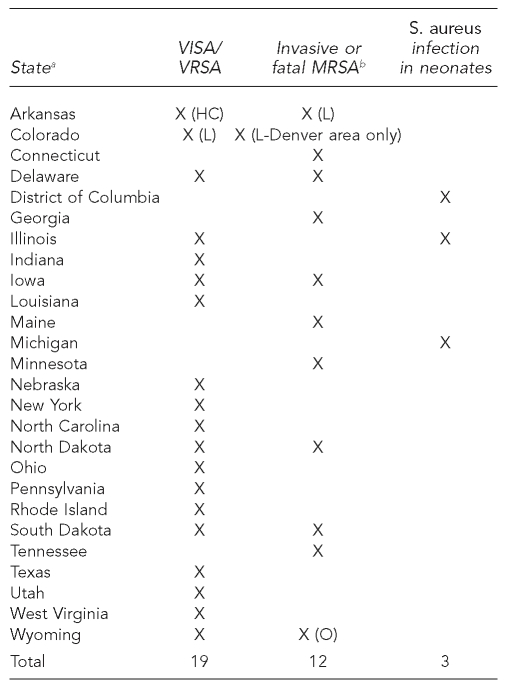

We propose a locally based, statewide model that will coordinate surveillance activities in the hospital and community, encourage communication between the two settings, and provide a more comprehensive assessment of the epidemiology of CA-MRSA. To create such an integrated system, S. aureus infection would become a reportable condition. Several states have added S. aureus to their lists of reportable conditions (Figure 1). While many require reporting of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus infections, the only cases of MRSA that are reportable are invasive (i.e., isolated from normally sterile sites) or fatal. The surveillance system proposed here would require reporting of cases of S. aureus infection that are both laboratory confirmed and non-laboratory confirmed.

Figure 1.

State reporting requirements for S. aureus infections

Source: In each case, the state department of health. Accessed in October 2006.

In addition to statewide surveillance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducts surveillance for invasive MRSA infections in select counties in nine states. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/abcs/team-start.htm#survareas

S. aureus = Staphylococcus aureus

VISA = vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus

VRSA = vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

L = laboratory only

O = outbreaks and clusters only

HC = health-care providers only

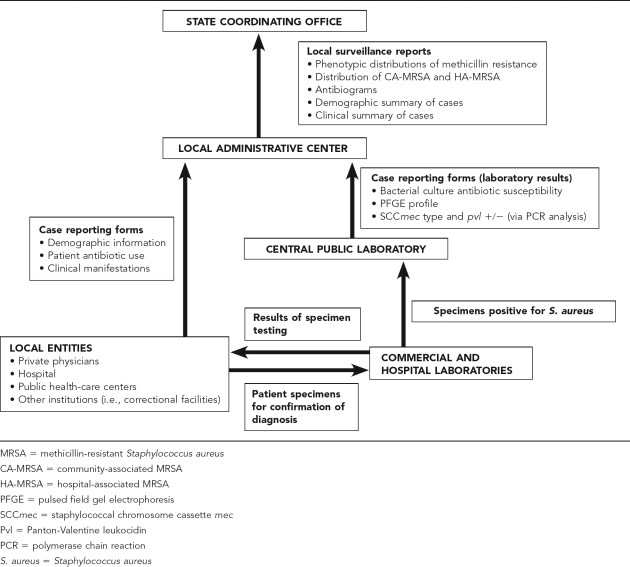

DESCRIPTION OF SURVEILLANCE MODEL

The integrated model involves two tiers (Figure 2). The first tier consists of a state-level coordinating office (possibly through the state health department) that is responsible for aggregating data and disseminating surveillance reports. The coordinating office determines standard microbiologic procedures, such as standards for susceptibility testing defined by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, and develops uniform reporting forms.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustrating model of integrated MRSA surveillance

The second level involves local surveillance activities. Hospitals, health-care facilities, private physicians, and other institutions (e.g., correctional facilities) within local areas are responsible for the collection of data from patients. Cases would be defined as patients with laboratory-confirmed S. aureus infection (clinical cases) and patients with presumed S. aureus infection that have not been laboratory confirmed (subclinical cases). All local entities record information on demographics (age, race/ethnicity, gender, municipality, or county of residence), antibiotic use, clinical manifestations, underlying disease, predisposing risk factors, and, if applicable, date of admission and onset.

Local entities comply with state regulations and the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regarding the collection of data (clinical and nonidentifying demographic information) and specimens for surveillance. HIPAA allows health-care providers to collect protected health information and release it to public health authorities for the purpose of preventing and controlling disease (HIPAA 45 CFR §164.512). Local entities also submit nasal swabs from all close contacts of the infected patient who are present at the time of examination and diagnosis. Local clinical laboratories submit specimens to a central local public health laboratory for further testing.

Many states currently require submission of patient information as well as specimens for testing to confirm diagnoses or to conduct additional testing (e.g., M. tuberculosis specimens for DNA typing). The central laboratory performs the following tests: bacterial culture, susceptibility testing, pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and polymerase chain reaction analysis of the SCCmec region and pvl genes. The central laboratory issues case reports stating the results of the tests performed. The results of the laboratory testing and the reporting forms are sent to a local administrative center. The local administrative center submits periodic reports on the local surveillance activities and findings for the following characteristics—phenotypic distribution of methicillin resistance (i.e., MRSA vs. MSSA), distribution of CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA (defined by PFGE typing), and the antibiogram of isolates (the average percent susceptibility of MRSA isolates to individual antibiotics), demographic composition of patients, and clinical information—to the state coordinating office.

The periodic reports include a comparison of the characteristics of cases in the community and hospital setting. The state coordinating office aggregates data and disseminates state- and local-level (e.g., municipal or county level) findings to hospitals, health-care facilities, private physicians, microbiologists, and public health officials. The coordinating office also develops and delivers educational workshops to providers, which includes education on reporting guidelines, information about the severity of CA-MRSA infection, methods for diagnosis, effective treatment courses, factors that facilitate transmission in the community (i.e., poor hygiene, close physical contact, shared items), and tools for patient education.

Because effective surveillance systems must be sensitive to local circumstances, the local entity, in consultation with state health authorities, should make specific decisions about allocation of staff time for the different tasks (i.e., collecting and managing information on patients, identifying contacts, coordinating laboratory testing).

THE CASE FOR AN INTEGRATED MODEL

A rigid distinction between the hospital and the community may soon become obsolete. The relative ease with which MRSA strains move between the hospital and the community certainly highlights the need for increased coordination between the two settings. The introduction of community strains into the hospital setting suggests that an extensive community reservoir might be expanding.12 Conversely, the increasing prevalence of MRSA in the hospital contributes to the carriage of endemic nosocomial strains into the community. Thus, the rise in CA-MRSA is most likely the result of both the introduction of nosocomial strains into the community and the de novo emergence of novel strains of pathogenic MRSA. In turn, the introduction of these community strains into the hospital setting represents another critical reservoir for MRSA.

The rising number of cases of CA-MRSA, the high prevalence of MRSA in certain communities, and the potential invisibility of community-circulating MRSA when prevalence assessments are solely clinic- or hospital-based make it important to determine and monitor trends at the community level. For instance, up to a third of the general population is colonized with S. aureus, but only 12% of the U.S. population is admitted to the hospital annually.33 Further, asymptomatic carriers represent an important contributor to the community reservoir, and the community is an ideal setting for surveying carriage. Control at the community level also has a direct effect on control in the hospital. Mathematical modeling reveals that successful control of hospital-based antibiotic-resistant infections, through prudent antibiotic use and standard infection-control measures, depends on the absence of the introduction of community strains into the hospital setting.41

Just as a strictly hospital-based surveillance system would exclude important data on the community, a community-based system would miss data on clinical MRSA infection and community transmission in the hospital. The hospital has also proven to be a somewhat unexpected setting for transmission of typical community strains.7–9 Hospital-based surveillance is an important tool for detecting clinical infections. Individuals with clinical MRSA infections may seek treatment in the hospital setting. A substantial increase in CA-MRSA case-patients admitted to the hospital could potentially increase the prevalence of nosocomial MRSA infections. Recent changes in our health-care systems have resulted in shorter hospital stays and, in turn, higher patient turnover.35 These changes may further facilitate the transmission of endemic hospital and possibly community strains back into the community. Patients who acquire MRSA in the hospital may not show clinical symptoms until they have returned to the community, as colonization can persist for several years before infection develops.32 Though the prevalence of endemic hospital strains in the community seems limited and the spread unknown, it is nonetheless important to quantify and monitor this trend.

Limitations

The model proposed has several limitations. A primary limitation is the heavy financial and human-resources burden needed to implement a statewide surveillance system. Because S. aureus would become a reportable condition under this model, the necessary costs and resources (including personnel, testing materials, storage, and transportation of specimens) would be borne by state and local government.

A second limitation is the mode of data collection and reporting: passive surveillance and reporting conducted by health-care providers. While underreporting by providers is a potential issue, the localization of data provided by this locally based, statewide system could serve as a strong incentive for timely and complete reporting by providers in the community and hospital setting. In this model, the data disseminated to providers could help guide their therapeutic choices for presumed staphylococcal infections.

CONCLUSION

The spread of MRSA is a dynamic phenomenon. The emergence of methicillin resistance in the community reflects the continuous evolution of an adaptive and virulent bacterium. Clearly, the rapid evolution of S. aureus necessitates consistent monitoring of its prevalence, distribution, and resistance patterns in the community and the hospital. The recent emergence of resistance to vancomycin—the primary line of therapy for multidrug-resistant S. aureus infections—and super-adapted Panton-Valentine leukocidin containing multidrug-resistant CA-MRSA strains, as well as evidence of a domesticated animal reservoir, reaffirm the importance of increased vigilance and continuing research to determine the epidemiological and genetic determinants of resistance, virulence, and transmission of MRSA.3,36,42 To achieve ultimate control of MRSA in the community, researchers, public health officials, and clinicians must continue to link knowledge of the microbiological and epidemiological dimensions of CA-MRSA with efforts to devise timely and appropriate population-level solutions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dietrich DW, Auld DB, Mermel LA. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in southern New England children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e347–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.e347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber JT. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41s(Suppl 4):S269–72. doi: 10.1086/430788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deresinski S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an evolutionary, epidemiologic, and therapeutic odyssey. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:562–73. doi: 10.1086/427701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Severe methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus community-acquired pneumonia associated with influenza—Louisiana and Georgia, December 2006–January 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(14):325–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zetola N, Francis JS, Nuermberger EL, Bishai WR. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an emerging threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:275–86. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg J. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in the community: who's watching? Lancet. 1995;346:132–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bratu S, Eramo A, Kopec R, Coughlin E, Ghitan M, Yost R, et al. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospital nursery and maternity units. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:808–13. doi: 10.3201/eid1106.040885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saiman L, O'Keefe M, Graham PL, 3rd, Wu F, Said-Salim B, Kreiswirth B, et al. Hospital transmission of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among postpartum women. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1313–9. doi: 10.1086/379022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection among healthy newborns—Chicago and Los Angeles county, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(12):329–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hidron AI, Kourbatova EV, Halvosa JS, Terrell BJ, McDougal LK, Tenover FC, et al. Risk factors for colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in patients admitted to an urban hospital: emergence of community-associated MRSA nasal carriage. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:159–66. doi: 10.1086/430910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlebois ED, Perdreau-Remington F, Kreiswirth B, Bangsberg DR, Ciccarone D, Diep BA, et al. Origins of community strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:47–54. doi: 10.1086/421090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carleton HA, Diep BA, Charlebois ED, Sensbaugh GF, Perdreau-Remington F. Community-adapted methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections (MRSA): population dynamics of an expanding community reservoir. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1730–8. doi: 10.1086/425019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diep BA, Gill SR, Chang RF, Phan TH, Chen JH, Davidson MG, et al. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2006;367:731–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan SL, Hulten KG, Gonzalez BE, Hammerman WA, Lamberth L, Versalovic J, et al. Three-year surveillance of community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infections in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1785–91. doi: 10.1086/430312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Begier EM, Frenette K, Barrett NL, Mshar P, Petit S, Boxrud DJ, et al. A high-morbidity outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among players on a college football team, facilitated by cosmetic body shaving and turf burns. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1446–53. doi: 10.1086/425313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Public health dispatch: outbreaks of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections—Los Angeles County, California, 2002–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(5):88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in correctional facilities—Georgia, California, and Texas, 2001–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(41):992–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma XX, Ito T, Tiensasitorn C, Jamklang M, Chongtrakool P, Boyle-Vavra S, et al. Novel type of Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec identified in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1147–52. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.4.1147-1152.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baba T, Takeuchi F, Kuroda M, Yuzawa H, Aoki K, Oguchi A, et al. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet. 2002;359:1819–27. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frazee BW, Lynn J, Charlebois ED, Lambert L, Lowery D, Perdreau-Remington F. High prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in emergency department skin and soft tissue infections. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:311–20. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naimi TS, LeDell KH, Como-Sabetti K, Borchardt SM, Boxrud DJ, Etienne J, et al. Comparison of community- and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. JAMA. 2003;290:2976–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okuma K, Iwakawa K, Turnidge JD, Grubb WB, Bell JM, O'Brien FG, et al. Dissemination of new methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in the community. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4289–94. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.11.4289-4294.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandenesch F, Naimi T, Enright MC, Lina G, Nimmo GR, Heffernan H, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes: worldwide emergence. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:978–84. doi: 10.3201/eid0908.030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussain FM, Boyle-Vavra S, Bethel CD, Daum RS. Current trends in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at a tertiary care pediatric facility. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:1163–6. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200012000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stemper ME, Shukla SK, Reed KD. Emergence and spread of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in rural Wisconsin, 1989 to 1999. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5673–80. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5673-5680.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez BE, Hulten KG, Dishop MK, Lamberth LB, Hammerman WA, Mason EO, Jr, et al. Pulmonary manifestations in children with invasive community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:583–90. doi: 10.1086/432475. Epub 2005 Jul 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groom AV, Wolsey DH, Naimi TS, Smith K, Johnson S, Boxrud D, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a rural American Indian community. JAMA. 2001;286:1201–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller LG, Perdreau-Remington F, Rieg G, Mehdi S, Perlroth J, Bayer AS, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Los Angeles. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1445–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellis MW, Hospenthal DR, Dooley DP, Gray PJ, Murray CK. Natural history of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization and infection in soldiers. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:971–9. doi: 10.1086/423965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adem PV, Montgomery CP, Husain AN, Koogler TK, Arangelovich V, Humilier M, et al. Staphylococcus aureus sepsis and the Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome in children. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1245–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mongokolrattanothai P, Boyle S, Kahana MD, Daum RS. Severe Staphylococcus infections caused by clonally related community-acquired methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant isolates. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1050–8. doi: 10.1086/378277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salgado CD, Farr BM, Calfee DP. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a meta-analysis of prevalence and risk factors. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:131–9. doi: 10.1086/345436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson AD, Enright MC. Evolutionary models of the emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3926–34. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3926-3934.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson LB, Bhan A, Pawlak J, Manzor O, Saravolatz LD. Changing epidemiology of community-onset methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:431–5. doi: 10.1086/502227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith DL, Dushoff J, Perencevich EN, Harris AD, Levy SA. Persistent colonization and the spread of resistance in nosocomial pathogens: resistance is a regional problem. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3709–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400456101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diep BA, Sensabaugh GF, Somboona NS, Carelton HA, Perdreau-Remington F. Widespread skin and soft-tissue infections due to two methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains harboring the genes for Panton-Valentine leucocidin. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2080–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.5.2080-2084.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Tenover FC, McDonald LC, Horan T, Gayes R. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Changes in the epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in intensive care units in US hospitals, 1992–2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:389–91. doi: 10.1086/499367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham PL, 3rd, Lin SX, Larson EL. A U.S. population-based survey of Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:318–25. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-5-200603070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuehnert MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Hill HA, McQuillan G, McAllister SK, Fosheim G, et al. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization in the United States, 2001–2002. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:172–9. doi: 10.1086/499632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fridkin SK, Hageman JC, Morrison M, Sanza LT, Como-Sabetti K, Jernigan JA, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in three communities. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1436–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiramatsu K, Cui L, Kuroda M, Ito T. The emergence and evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:486–93. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Altman LK. Pet-human link studied in resistant bacteria. New York Times. 2006 Mar 22; Sect. A:20. [Google Scholar]