SYNOPSIS

Objective

The purpose of this study was to compare the burden of disease experienced by people with mental health conditions with people who have common medical disorders. Three prevalent medical disorders—the burden of disease of back/neck problems, diabetes, and hypertension—were compared with the mental health category of depression, anxiety, or emotional problem.

Methods

This study used data from the nationally representative 2003–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey for respondents aged 18 or older (n=4,833). The measurement of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) used was the Healthy Days Measures developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Unadjusted and adjusted HRQOL were compared for individuals reporting each of the four conditions. Adjusted HRQOL was assessed using ordinary least squares regression, which controlled for gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, comorbidity, and income.

Results

Individuals with mental health conditions experienced 17.6 total unhealthy days per month, while those with back and neck problems and those with hypertension experienced 12.2 total unhealthy days per month, and those with diabetes experienced 12.3 total unhealthy days per month. After adjusting for socioeconomic and demographic characteristics as well as comorbid conditions, mental health conditions were responsible for a 6.8-day decrease in healthy days per month compared with average adults (p<0.001). Mental health conditions resulted in significantly lower HRQOL than back or neck problems (p=0.053), diabetes, (p=0.002), and hypertension (p=0.012).

Conclusions

There were significant differences between the HRQOL found in mental and medical conditions, with mental health conditions being responsible for significantly greater impairment of HRQOL. An efficient health-care system should consider the relative disease burden of specific conditions when allocating public health resources.

Throughout much of history in the Western world, health was understood simply as the opposite of sickness, and sickness as the opposite of health. Limiting the consideration of these concepts in this manner constrains the ability of the medical community and society to appreciate the more subtle complexities of health and disorder. A more comprehensive understanding is gaining popularity in the West as more is learned about wellness and correlates of disease such as disability and dysfunction.1,2 A concept called health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is one product of the changing understanding of health and disorder. HRQOL measurements reflect perceived health and life satisfaction over a period of time.3 Different than other methods of evaluation, HRQOL measurement focuses on the individual's own observations of impairment and health, and thus provides a glimpse into the effects of this diagnosis and is, arguably, the best indication of the impact of disease on an individual's life.

One metric of HRQOL, created by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Healthy Days Measures, allows for dramatically different diseases to be compared using the same measurement. Generally, it is difficult to compare the burdens of different disorders because their effects are often dissimilar and unrelated; however, the Healthy Days Measures are able to translate the unique effects of different diseases into a common language, called “unhealthy days,” for easy and effective comparison.

Just as our understanding of health is evolving, so is the nature of health issues confronting humanity. The past century saw a categorical transition in the developed world in the leading causes of death from infectious diseases to chronic conditions.4 Today, 70% of the U.S. population dies from diseases in this class, which absorbs more than $700 billion a year—more than 70% of health-care expenditures in the nation.4,5

This study specifically compared HRQOL of people in the U.S. with chronic medical conditions (diabetes, back/neck problem, and hypertension) with the HRQOL of those with a mental health condition (depression, anxiety, or emotional problem). This assessment offers valuable insight into the differences in perceived health and quality of life for these populations, as there is still much that is unknown about the disability and impairment associated with mental health conditions, which contributes to stigma and discrimination.

Formulating an association with medical disorders, whose effects we are more familiar with, might construct a frame of reference as we examine the societal and individual impacts of mental health conditions. The medical conditions selected were chosen for comparison because of their high prevalence, professional and public familiarity, and because they are symptomatic (depression, back and neck pain, diabetes) and nonsymptomatic (hypertension).

A recent study by Gerberding showed that diabetes poses a serious, and growing, health threat to the country.6 This preventable disease directly cost $92 billion in the U.S. in 2002, and an additional $40 billion in indirect costs. As of 2005, 14.6 million Americans have been diagnosed with diabetes—a number more than twice that of 15 years ago. Furthermore, an additional 6.2 million Americans have undiagnosed cases. For those people born in the U.S. in the year 2000, one in three are projected to develop the disease.

The next condition, back/neck problem, encompasses disorders that range from back or neck injury to disk disorders and other related conditions.7 Approximately $9 million in Workers' Compensation costs and 100 million days of work are lost yearly because of back pain alone.8,9 In 2004, more than 45 million visits were made to physicians and more than 1.5 million hospitalizations occurred because of back or neck problems.7

The last of the medical conditions examined, hypertension, affects almost one in every three American adults, and caused or contributed to 277,000 deaths in the U.S. in 2003.10,11 For the year 2006, hypertension costs reached approximately $63.5 billion.11 Because of its prevalence and severity, hypertension rounds out the three medical conditions examined by this survey.

In America, in a given year, more than 25% of adults have a clinically diagnosable mental health condition, which translates to approximately 75 million individuals in 2006.12,13 Not including research costs, the U.S. spends $150 billion on mental health disorders each year.14 Mental health disorders can be pervasively disabling, limiting functioning, impairing quality of life, contributing to emotional distress, and causing discrimination and alienation.15 Not only can mental health disorders be debilitating, they can also contribute to death. Of those who commit suicide, which claimed 32,439 lives in the U.S. in 2004, 90% are estimated to have a mental health disorder.16,17

In a groundbreaking study by Murray and Lopez, projections show that depression will eclipse other disorders and rank second in terms of burden of disease by the year 2020.18 As part of their study, Murray and Lopez had health-care professionals around the world rank disorders in terms of the severity of disability associated with each. Surpassing Down's syndrome and below-knee amputation, depression was ranked in the same category as paraplegia and blindness. Our study differs in that Murray and Lopez utilized the opinions of health-care professionals, and while there is great value to this information, the Healthy Days Measurements give more insight into the actual perceived burden of disorder from those who experience it firsthand, because of their basis in self-report. Also, the data used in this study are more current, filling a void left since the 1990 data used by Murray and Lopez garnered important information about the burdens of disease.

METHODS

This study used extant data from the 2003–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). NHANES is a biennial, nationally representative survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), a division of CDC. The survey targets the noninstitutionalized, civilian U.S. population through a stratified, multistage probability sample design. The 2003–2004 NHANES had a sample size of 10,122, and oversampled Mexican Americans, African Americans, people with low income, and those aged 60 years or older. Most often, the survey was conducted in the participant's home through computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI). A more complete description of the NHANES and survey instruments can be found at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.

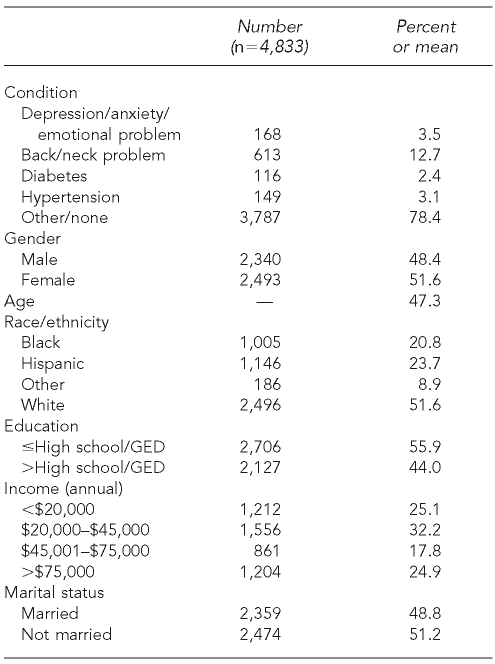

This study was limited to adults aged 18 and older, resulting in a sample of 4,833 people. Characteristics of this sample are displayed in Table 1. There were 1,046 individuals who self-reported experiencing difficulty as a result of one of the selected conditions. In all, 168 (3.5%) reported a mood disorder (depression, anxiety, or emotional problem), 613 (12.7%) reported a back or neck problem, 116 (2.4%) reported diabetes, and 149 (3.1%) reported hypertension. There were 3,787 individuals who did not report any of the four conditions. Because each of the four conditions examined often co-occur with other medical conditions, the analyses also controls for the presence of arthritis, cancer, fractures, heart disease, lung disease, problems associated with stroke, and weight problems.

Table 1.

Characteristics of sample aged 18 years

GED = General Educational Development

Source: 2003–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Unhealthy days

The utilized Healthy Days Measures questions included: “Thinking about your physical health, which includes physical illness and injury, for how many days during the past 30 days was your physical health not good?” and “Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?” The indicator this study utilizes is called “unhealthy days”—the number of physically unhealthy days and mentally unhealthy days combined. Thirty unhealthy days total in the past 30 days is the maximum allowable, so a person with a sum surpassing 30 is assigned this cap value. A method with maximum overlap (in which unhealthy days could reach 60) was found inappropriate after examining the actual response pattern in which most people reported uniquely physically or mentally unhealthy days.2 Many published studies attest to the validity and consistency of the Healthy Days Measures for quantifying HRQOL.19–27

Statistical analysis

All results are calculated using the weights provided by the NCHS to allow for nationally representative estimates with standard errors that correctly account for the complex sampling design. The multivariate regression analysis controlled for gender, age, race/ethnicity, level of education, marital status, annual income, and presence of comorbid conditions, allowing for estimates of the independent impact of each of the self-reported conditions on unhealthy days.28 The comorbid conditions were controlled for in the models with indicator variables for each of the seven potential additional conditions (arthritis, cancer, fractures, heart disease, lung disease, stroke, and weight problems).

To better understand the influence of comorbid conditions on the disability associated with individuals with a mental disorder, the regression model was first estimated with only the mental health condition indicator variable, with all other condition variables removed. The model was next estimated with the dummy variables of the three comparator conditions added to the model, and then a third model was estimated with all medical condition indicator variables included. Adjusted Wald tests were run to determine if the three comparator medical conditions were associated with more unhealthy days than the mental health conditions after adjusting for the covariates.29

RESULTS

American adults reported a mean of 7.9 unhealthy days per month. Individuals with mental health disorders reported 17.6 unhealthy days per month, while those with back or neck problems reported 12.2 unhealthy days per month, those with diabetes reported 12.3 unhealthy days per month, and those with hypertension reported 12.2 unhealthy days per month. To account for potential differences in age, gender, race, marital status, income, and education among the groups reporting these conditions, multivariate analyses were estimated. When only mental health disorders were included in the model, these disorders were associated with an additional 10.6 unhealthy days per month (results not shown).

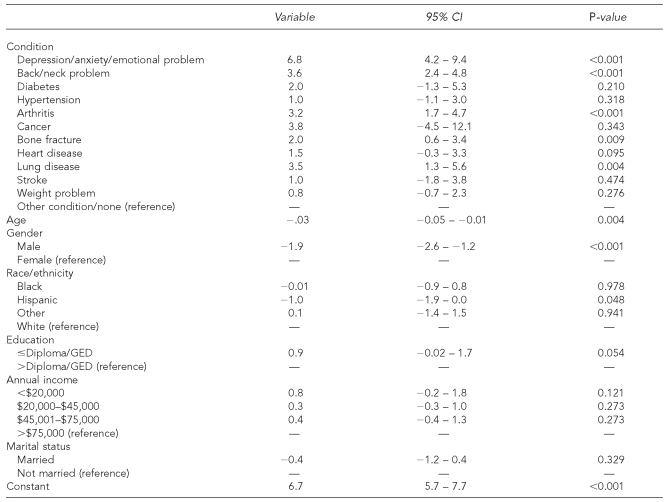

Next, the indicator variables for hypertension, back and neck problems, and diabetes were added to the regression model (results not shown). After adjusting for these variables, individuals with mood disorders experienced 7.8 additional unhealthy days than people without those disorders (p<0.001). Finally, indicator variables for the three comparator conditions, as well as the seven control conditions, were included in the model (Table 2). After adjusting for all of these conditions, individuals with mood disorders experienced a mean of 6.8 additional unhealthy days per month (p<0.001). Individuals with a back or neck problem had 3.6 more unhealthy days than those without such a problem (p<0.001). Individuals with diabetes or hypertension did not have more unhealthy days than individuals who did not report those conditions, reporting an additional 2.0 days (p=0.210) and 1.0 days (p=0.318), respectively.

Table 2.

Results of regression analysis for health-related quality of life, measured by unhealthy days

GED = General Educational Development

CI = confidence interval

Source: 2003–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Adjusted Wald tests were then conducted to determine if the impact of having a mood disorder was significantly greater than either of the three medical conditions after controlling for all of the other variables, including the seven other medical conditions. Individuals with mental health conditions had significantly more unhealthy days than those with back and neck problems (p=0.053), diabetes (p=0.002), and hypertension (p=0.011). In fact, those with mental health conditions had significantly more unhealthy days than those with all conditions controlled for in the analysis except for cancer (3.8 additional days; p=0.343) and lung disease (3.5 additional days; p=0.081).

DISCUSSION

The results suggest that people with mood disorders experience many more unhealthy days each month than the general population, as well as significantly more unhealthy days than those with nearly all medical conditions examined, although these medical conditions were still associated with lower HRQOL. For the 20.8 million Americans with diabetes, 12.3 unhealthy days means about 40% of the month will be spent with poor HRQOL.6 For the numerous American adults with back/neck problems or 65 million Americans with hypertension, an average of 12.2 unhealthy days were observed, also comprising 40% of each month.10

While these numbers are all valuable indications of the lowered HRQOL that accompanies health conditions, the results for mental health conditions are especially notable. Individuals with mental health conditions had 17.6 unhealthy days every month, indicating that more than half of each month is spent with poor HRQOL. Juxtaposing the HRQOL of people with mental health conditions with the HRQOL of those with medical conditions, we see that mental health conditions bring a substantially greater number of unhealthy days, and thus cause more impairment of HRQOL. Depression and other mood disorders commonly co-occur with other health conditions, thus increasing the number of unhealthy days experienced by this population. However, even after controlling for comorbid medical conditions, these mental health conditions are still associated with significantly more unhealthy days than all conditions examined, except for cancer and lung disease.

There are multiple implications of the results found by this study. Chiefly, the cloud of uncertainty about how much mental health conditions affect individuals is made more transparent by these findings. This information could be applied to raise awareness and appreciation for mental health conditions, and reduce stigma, potentially increasing the number of people who come forward for treatment. The findings also support a reevaluation of U.S. health-care priorities.

While it is natural to direct our attention to the more obviously devastating diseases, which present concrete death tolls and statistics, this study finds that there are more complexities to disorders than mortality rates alone. When evaluating disease, consideration should extend beyond matters of mortality, and interventions should have the aim of improving the quality of life and functioning of patients. Admittedly, these analyses do not account for differing mortality rates of the four conditions examined, but these results show how these conditions affect those individuals who are living with them. Accordingly, more money should be allocated to development of ways to improve HRQOL, and to research on conditions that are found to especially diminish HRQOL, such as mental health conditions.

Another major implication of the association of significantly lower HRQOL with mental health conditions is the new advantage this knowledge can give to diagnostic procedures and detection of mental health conditions. As proposed by Spitzer and colleagues, who studied patterns of impairment for various conditions, patients who present with levels of HRQOL atypically low for a person with their medical diagnoses, or those who have demonstrated a worsening of HRQOL without apparent medical cause, should be evaluated for previously undetected or newly developed mental health conditions, as it is clear they can greatly influence HRQOL.3

An additional implication stems from the self-report nature of this study. Idler and Benyamini found a correlation between self-rated health and health-related actions, and that feelings of poor health might contribute to self-neglect when it comes to accessing medical care or complying with treatments.30 This implies the need for increased monitoring by health-care providers of patients with mental health disorders for unreported illness and treatment adherence.

Limitations

There are a few limitations to this study that should be mentioned. One limitation is that conditions are self-reported, leaving room for error in respondent recall or report. However, there is no real way to get the data necessary to determine HRQOL without relying on self-report, so if it is a limitation, self-report is a necessary one.3

Another related limitation that could be proposed is that people with mental health disorders give pessimistic self-report due to the nature of their conditions. However, Spitzer and colleagues found distinct and individual patterns of impairment in various diagnostic categories of mental health disorders, contradicting the idea of reporting bias by the respondents with mental health conditions.3 Regardless of concordance of patient measured and independently measured ratings, patient experience of health should not be disregarded.3 It should also be noted that people with extremely severe cases of disorder may have been undersampled because they could not participate in the survey process due to the extent of their limitations.

Finally, the NHANES is a household interview survey, and several groups that traditionally experience severe mental health disorder disproportionately, such as the institutionalized and the homeless, were possibly excluded from the survey because of the household requirement.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study offer valuable information about the reduced HRQOL that is associated with mental health conditions. The primary finding of this study is that people with mental health conditions perceive strikingly low HRQOL. When that is applied to the almost 58 million Americans who have mental health conditions, it is not an exaggeration to say that there is a public health crisis regarding quality of life for people with mental health disorders. As Druss and colleagues explained, “Understanding the prevalence and correlates of disability in patients with mental… illness can be an important first step in improving these individuals' functional status and quality of life.”31

REFERENCES

- 1.Carr AJ, Gibson B, Robinson PG. Measuring quality of life: is quality of life determined by expectations or experience? BMJ. 2001;322:1240–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Measuring healthy days: population assessment of health-related quality of life. Atlanta: CDC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, Hahn SR, Williams JB, deGruy FV, 3rd, et al. Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental health disorders. Results from the PRIME-MD 1000 Study. JAMA. 1995;274:1511–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Indicators for chronic disease surveillance. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004;53(RR-11):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) The state of aging and health in America 2004. [cited 2006 Dec 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/State_of_Aging_and_Health_in_America_2004.pdf.

- 6.Gerberding JL. Diabetes: disabling, deadly, and on the rise. Atlanta: CDC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Information about orthopaedic patients and conditions. [cited 2006 Dec 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.aaos.org/Research/stats/patientstats.asp.

- 8.Atlas SJ, Wasiak R, van den Ancker M, Webster B, Pransky G. Primary care involvement and outcomes of care in patients with a workers' compensation claim for back pain. Spine. 2004;29:1041–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200405010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo HR, Tanaka S, Halperin WE, Cameron LL. Back pain prevalence in U.S. industry and estimates of lost workdays. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1029–35. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.7.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fields LE, Burt VL, Cutler JA, Hughes J, Roccella EJ, Sorlie P. The burden of adult hypertension in the United States, 1999 to 2000: a rising tide. Hypertension. 2004;44:398–404. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000142248.54761.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, Howard VJ, Rumsfeld J, Manolio T, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2006 update. Circulation. 2006;113:e85–e151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.171600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Census Bureau. Table 1: Annual estimates of the population for the United States, regions, and states and for Puerto Rico: April 1, 2000, to July 1, 2006. [cited 2007 Mar 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/popest/states/tables/NST-EST2006-01.xls.

- 14.President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (US) Achieving the promise: transforming mental health care in America. Rockville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services (US); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Prevention and promotion in mental health. Geneva: WHO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. [cited 2007 Mar 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars.

- 17.Conwell Y, Brent D. Suicide and aging I: patterns of psychiatric diagnosis. Int Psychogeriatr. 1995;7:149–64. doi: 10.1017/s1041610295001943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray JL, Lopez AD. Summary: the global burden of disease. Boston: Harvard School of Public Health; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andresen EM, Fouts BS, Romeis JC, Brownson CA. Performance of health-related quality-of-life instruments in a spinal cord injured population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:877–84. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andresen EM, Catlin TK, Wyrwich KW. Retest reliability and validity of a surveillance measure of health-related quality of life. Quality of Life Research. 2001;10:199. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andresen EM, Catlin TK, Wyrwich KW, Jackson-Thompson J. Retest reliability of surveillance questions on health related quality of life. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:339–43. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.5.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Health-related quality of life and activity limitation—eight states, 1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47(7):134–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Health-related quality of life—Puerto Rico, 1996–2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(8):166–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hennessy CH, Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Scherr PA, Brackbill R. Measuring health-related quality of life for public health surveillance. Public Health Rep. 1994;109:665–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moriarty DG, Zack MM. Validation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Healthy Days measures; Abstracts Issue, 6th Annual Conference of the International Society for Quality of Life Research; Barcelona, Spain. 1999. p. 617. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nanda U, Andresen EM. Performance of measures of health-related quality of life and function among disabled adults. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:644. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ôunpuu S, Chambers LW, Chan D, Yusuf S. Validity of the US Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System's health related quality of life survey tool in a group of older Canadians. Chronic Dis Can. 2001;22:93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greene WH. Econometric analysis. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice-Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crichton N. Wald test. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10:774. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Druss BG, Marcus SC, Rosenheck RA, Olfson M, Tanielian T, Pincus HA. Understanding disability in mental and general medical conditions. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1485–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]