SYNOPSIS

Objectives

The aim of this study was to provide state-level surveillance data to assess the oral health of people with disabilities.

Methods

Data from the 2004 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)—a state-based, random-digit-dialed telephone survey of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population 18 years of age and older—were used to estimate disability prevalence and state-level differences in oral health among people with and those without disabilities.

Results

Nationally, people with disabilities were less likely than people without disabilities to visit a dentist or dental clinic in the past year. The percentage of people with disabilities who reported they had visited a dentist in the past year was lowest in Mississippi (48.9%) and highest in Connecticut (74.5%). Among people without disabilities reporting they had visited a dentist or dental clinic in the past year, the percentage was lowest in Mississippi (60.7%) and highest in Minnesota (80.7%). Edentulism was higher among people with disabilities compared with those without disabilities. Among people with disabilities, edentulism was lowest in the District of Columbia (4.1%) and highest in Kentucky (18.7%). Among people without disabilities, edentulism was lowest in California (2.7%) and highest in Kentucky (11.3%).

Conclusions

Despite numerous studies and reports documenting the unmet oral health needs of people with disabilities, there has been no systematic national surveillance of oral health among people with disabilities in the United States. This article provides much-needed state-by-state and national epidemiologic data regarding the oral health of people with disabilities.

Oral health and the need for preventive care might be considered by the public, nondental health-care providers, and policy makers to be less important than other health needs.1 This assumption could be particularly true for the 51 million individuals with disabilities, including 35 million Americans with severe disabilities, in 2002,2 whose health might limit access and use of preventive oral health services.3 People with certain disabilities may be at greater risk for oral disease, which, in turn, may further compromise their health.1 A report from the Institute of Medicine showed oral health problems as a leading secondary health condition that many people with disabilities endure.4 The Surgeon General's report1 and his Call to Action to Promote Oral Health5 highlighted research that showed associations between oral infections and a variety of diseases including diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. More recently, the Surgeon General's Call to Action to Improve the Health and Wellness of People with Disabilities noted that more than 10% of people with disabilities listed these aforementioned diseases as the primary conditions leading to their disability.6

Results from numerous studies described in the Surgeon General's report on oral health1 and noted in other reports3–7 suggest that good oral health is key to improving general health, self-esteem, communication, nutrition, and the quality of life for people with disabilities. Despite condition-specific disability studies and reports identifying opportunities to improve oral health, there has been no state-level surveillance of oral health among people with disabilities in the U.S. Thus, the aim of this study was to provide surveillance data to address the recent call to action5 and assess the oral health of people with disabilities.

Using data from the 2004 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), we quantified the use of oral health services (as measured by dental visit patterns and having had teeth cleaned) and tooth loss for people with and without disabilities for each U.S. state and the District of Columbia (DC). Such surveillance is essential for identifying individual needs, increasing public awareness, informing federal, state, and local oral health planning and policy, and allocating resources to reduce disparities in oral health care.

METHODS

Data sources

The data for this study were obtained from the BRFSS, a state-based, random-digit-dialed telephone survey of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population 18 years of age or older.8,9 For the survey, which is conducted by all states with assistance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), trained interviewers collect comprehensive demographic, health, behavioral health risk, and preventive health data. The data are used to quantify state-level prevalence of major health behavioral risks associated with premature morbidity and mortality and to evaluate their impact. In turn, this information is used to facilitate the development and evaluation of state health promotion and disease prevention programs. A detailed description of the compilation and use of BRFSS data is available online at www.cdc.gov/brfss/.

Disability definition

In 2004, BRFSS respondents in each state were asked two disability screening questions: (1) “Are you limited in any way in any activities because of physical, mental, or emotional problems?” and (2) “Do you now have any health problem that requires you to use special equipment, such as a cane, a wheelchair, a special bed, or a special telephone?” We defined people as having a disability if they answered “yes” to either of these questions. People who did not respond, refused to respond, or whose responses were missing were excluded from the analysis.

Oral health

Three questions were used to determine respondent use of oral health services and tooth loss. Specifically, BRFSS respondents were asked: (1) “How long has it been since you last visited a dentist or a dental clinic for any reason?”, (2) “How many of your permanent teeth have been removed because of tooth decay or gum disease?”, and (3) “How long has it been since you had your teeth cleaned by a dentist or dental hygienist?” The number of permanent teeth removed excluded those lost due to other illness or injury but included wisdom tooth loss and tooth loss due to infection. Respondents who reported never having visited a dentist or having all their permanent teeth removed were not asked how long it had been since they had their teeth cleaned by a dentist or dental hygienist. People who did not respond, refused to respond, or whose responses were missing were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical analysis

State-level prevalence of disability, dental visits, tooth loss, and dental cleanings were obtained using the SAS-callable version of SUDAAN.10,11 We used SUDAAN to account for the BRFSS complex survey design. State-level estimates of respondents' use of oral health services and tooth loss were weighted and age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population.12 Data for Hawaii were not available for 2004.

RESULTS

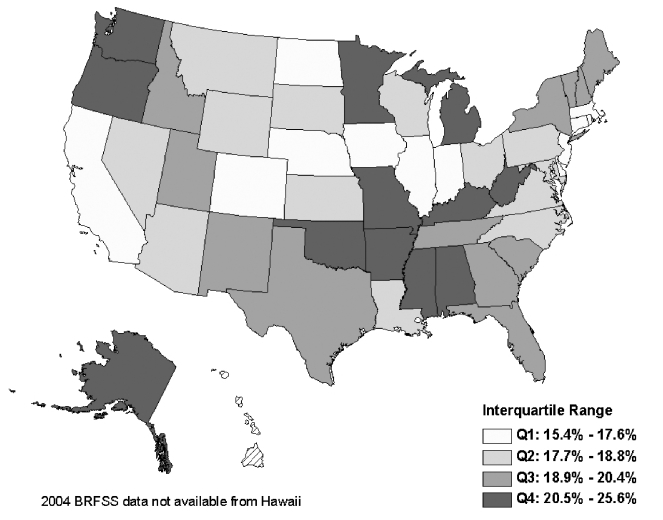

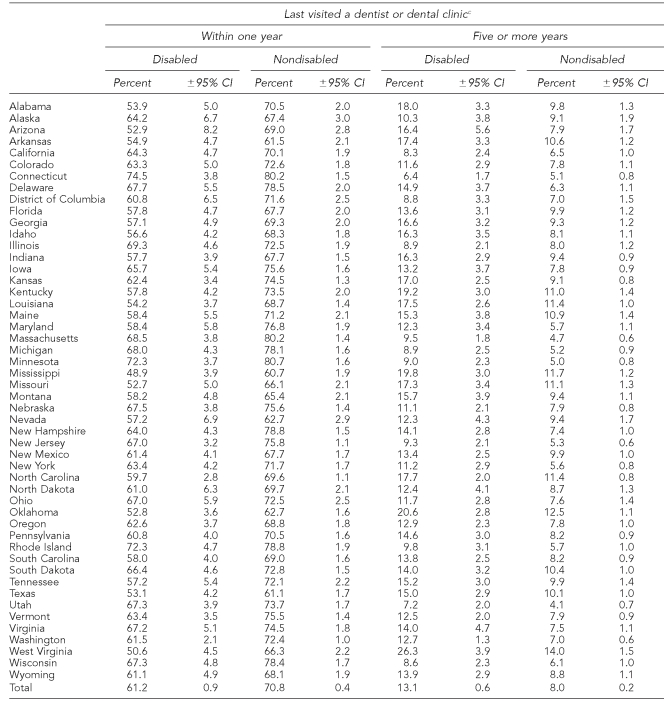

The self-reported prevalence of people with a disability was lowest in DC and Iowa (15.4%) and highest in West Virginia (25.6%) (Figure). The percentage of people with disabilities who reported they had visited a dentist or dental clinic in the past year was lowest in Mississippi (48.9%) and highest in Connecticut (74.5%) (Table 1). Among people without disabilities reporting they had visited a dentist or dental clinic in the past year, the percentage was lowest in Mississippi (60.7%) and highest in Minnesota (80.7%). In all 49 states and DC, the percentage of respondents with a disability was lower than respondents without a disability reporting that they had visited a dentist or dental clinic in the past year. Comparing people with disabilities and those without, Maryland had the greatest difference (18.4 percentage points) in people reporting they had visited a dentist or dental clinic in the past year.

Figure.

Age-adjusted prevalence of disability among adults 18+ years of age, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2004

Table 1.

Prevalence of dental visits by disability status and state/area: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 49 states, and the District of Columbia, 2004a,b

People aged 18 years or older

Hawaii completed three of 12 months of interviews in 2004; these data are not available in the aggregate 2004 dataset.

Potential responses since respondent last visited a dentist or a dental clinic for any reason included: within one year; within the past two years (one year but less than two years); within the past five years (two years but less than five years or more); five or more years; and none, don't know, or refused to respond. As before, people who did not respond, refused to respond, or whose responses were missing were excluded from the analysis. We only show estimates for the lower- and upper-bound responses given volume of information and space concerns. However, estimates for more than one year and less than five years may be gleaned by subtracting the estimates shown from 100. For example, the percentage of Alabama disabled respondents who visited a dentist more than one year ago but less than five years ago is 28.1% (100−(53.9+18.0)).

CI = confidence interval

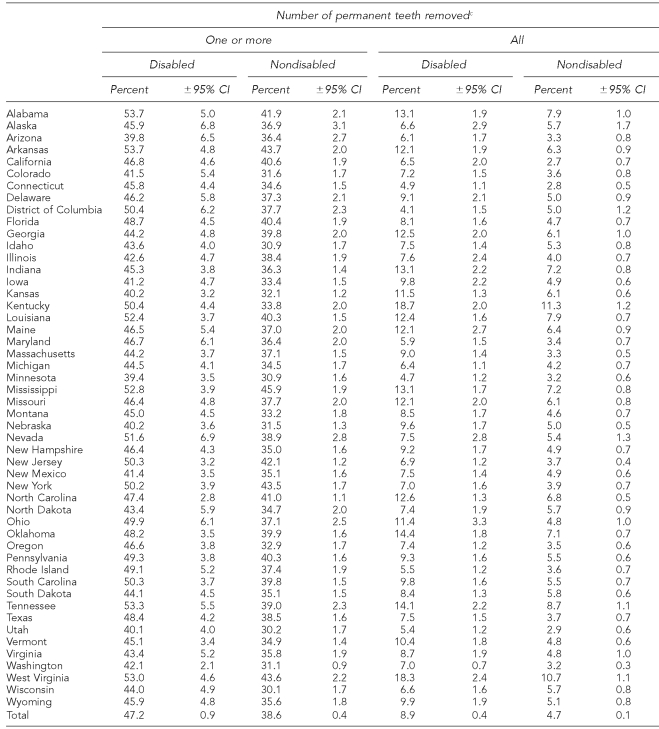

The self-reported prevalence of tooth loss was higher among people with disabilities when compared with people without disabilities (Table 2). Total tooth loss for people with disabilities was lowest in DC (4.1%) and highest in Kentucky (18.7%). Among people without disabilities, total tooth loss was lowest in California (2.7%) and highest in Kentucky (11.3%). With the exception of DC, people with disabilities were more likely to report edentulism compared with those without disabilities. Comparing people with disabilities and those without, West Virginia had the greatest difference (7.6 percentage points) in edentulism.

Table 2.

Prevalence of tooth loss by disability status and state/area—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 49 states and the District of Columbia, 2004a,b

People aged 18 years or older

Hawaii completed three of 12 months of interviews in 2004; these data are not available in the aggregate 2004 dataset.

Potential responses for the number of permanent teeth removed because of tooth decay or gum disease included: one to five; six or more (not all); all; and none, don't know, or refused to respond. As before, people who did not respond, refused to respond, or whose responses were missing were excluded from the analysis. We only show estimates for the lower- and upper-bound responses given volume of information and space concerns.

CI = confidence interval

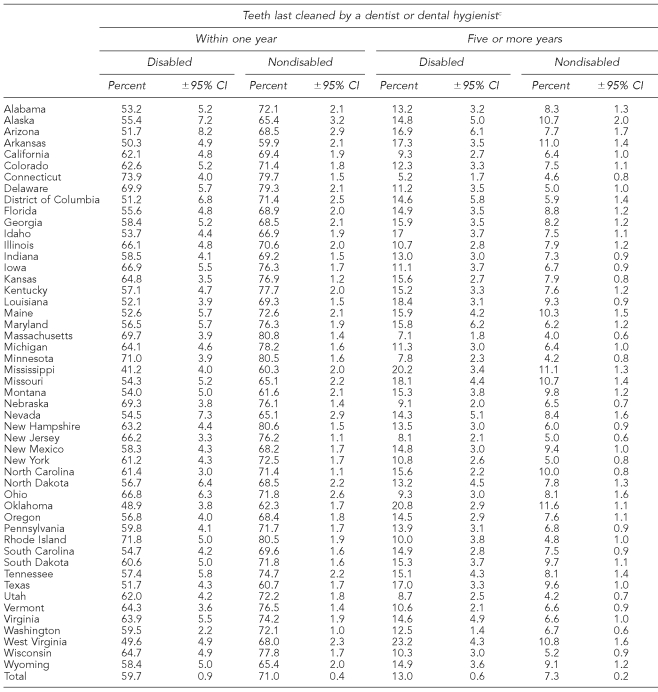

The percentage of people with disabilities who reported having their teeth cleaned by a dentist or dental hygienist in the past year was lowest in Mississippi (41.2%) and highest in Connecticut (73.9%) (Table 3). For people without disabilities who reported having their teeth cleaned in the past year, the percentage was lowest in Arkansas (59.9%) and highest in Massachusetts (80.8%). Comparing people with disabilities and those without, Kentucky had the greatest difference (20.6 percentage points) in people reporting they had their teeth cleaned by a dentist or dental hygienist in the past year. (Note: See respective tables for details of confidence intervals.)

Table 3.

Time since last dental cleanings by disability status and state/area— Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 49 statesa and the District of Columbia, 2004a,b

People aged 18 years or older

Hawaii completed three of 12 months of interviews in 2004; these data are not available in the aggregate 2004 dataset.

Potential responses since respondents last had their teeth cleaned by a dentist or a dental hygienist included: within one year; within the past two years (one year but less than two years); within the past five years (two years but less than five years or more); five or more years; and none, don't know, or refused to respond. As before, people who did not respond, refused to respond, or whose responses were missing were excluded from the analysis. We only show estimates for the lower- and upper-bound responses given volume of information and space concerns. However, estimates for more than one year and less than five years may be gleaned by subtracting the estimates shown previously from 100. For example, the percentage of Alabama disabled respondents who last had their teeth cleaned by a dentist or a dental hygienist more than one year ago but less than five years ago is 33.6% (100−(53.2+13.2)).

CI = confidence interval

DISCUSSION

Our findings reveal substantial disparities in receipt of oral health care and tooth loss among people with disabilities when compared with people without disabilities. Although teeth are lost for many reasons, most teeth are lost because of periodontal disease, dental caries, or trauma.13,14 The World Health Organization lists 120 diseases and conditions that have oral manifestations.15 Many of these diseases may be disabling, including diabetes,1,16 heart disease,17–20 stroke,21,22 and osteoporosis,23–25 and can be associated with periodontal disease. The aforementioned diseases may also manifest as secondary conditions that are associated with, and may increase the severity of, the primary disabling condition.4,6 More than 400 over-the-counter and prescription drugs, including tricyclic antidepressants, antihistamines, and diuretics, that may be used to treat primary disabling conditions, or secondary conditions (e.g., depression) that are associated with disability, can have xerostomic side effects that may increase the risk of oral infections.26 Thus, individuals with disabilities who use these medications may be at greater risk for oral diseases.1

Disability can also adversely affect social functioning, mental health, and quality of life.4,6 Tooth loss can exacerbate these adverse effects if it increases the self-consciousness of people with disabilities or causes them to avoid or limit conversation, laughing, and smiling, or become depressed and withdrawn.27–30 Early recognition and professional intervention, including clinical preventive care and health education, can reduce or eliminate many of these problems.

Expenditures for dental services in the U.S. are projected to be $90 billion in 2006. During the period 2006 through 2014, dental service expenditures are expected to increase 63% to $147 billion.31 These estimates denote dental expenditures that will be delivered by dentists in practice settings. Thus, they understate total dental expenditures because they do not account for dental services delivered in other settings and expenses related to hospitalization and long-term care from conditions associated with poor oral health. For example, unmet oral health needs that aggravate the primary disabling condition or increase one's susceptibility to secondary conditions may adversely affect everyday activities (e.g., feeding one's self, shopping for groceries). This may, in turn, directly result in or exacerbate nutritional problems32–38 that erode general health, and result in an increase in the number of hospitalizations or premature nursing home entry among people with disabilities.

Because the federal Medicare program and state Medicaid programs can pay for hospital and long-term care expenditures incurred by people with disabilities, both federal and state governments have a financial interest in improving the oral health of this population. That is, health-promotion activities that improve oral health will reduce oral diseases and infections and any expenditures associated with treating these conditions. In addition, if improvements in oral health improve general health, the outcome could be associated with reductions in the number of hospitalizations, delays or prevention of nursing home entry, and even a slowing of the projected growth rates in national health-care expenditures.

The Surgeon General's report1 and call to action5 to promote oral health noted that the identification of oral health needs is limited by the lack of epidemiologic and surveillance databases at national, state, and local levels to identify oral health disparities and patterns of disease. We believe that this article provides federal and state programs with epidemiologic evidence of the oral health needs of people with disabilities.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the BRFSS telephone survey might understate the true prevalence of disability because it excludes the institutionalized population, people in households without telephones, and those whose disability prevents them from answering the telephone. Alternately, the BRFSS telephone survey might overstate the prevalence of disability because it does not ask about the permanence of the disabling condition. Second, data for disability and oral health are based on self-reports and have not been validated. Third, condition-specific disabilities (e.g., diabetes), duration, and severity of disability are associated with an increased likelihood of oral health disparities. The questions used to define a disability do not define the type, duration, or severity of the disability and, as a consequence, the results might be biased.

Fourth, the question used to define tooth loss counted the removal of wisdom teeth. However, the loss of third molars may reflect the removal of an impaction and not necessarily signal poor quality care. Fifth, unmet oral health needs coupled with disease-specific conditions can be debilitating. However, it was beyond the scope of this analysis to characterize any causality between oral health and disability. Sixth, other factors including demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related characteristics might be associated with the use of oral health services and tooth loss. It was beyond the scope of our analysis to control for such factors. However, in future work we plan to use multivariate analytical techniques to account for their potential confounding effects.

Seventh, our definition of oral health is limited to periodic professional assessments, cleanings, and tooth loss. Daily hygiene routines, promotion of a healthy lifestyle, and community activities, including water fluoridation, dental sealant applications for children, tobacco cessation campaigns, and the use of mouth guards in sports, should also be considered in assessing access to and use of oral health disease prevention methods.1

CONCLUSIONS

In the U.S., the oral health status of people with disabilities needs to be addressed. Oral health is important to the general health and well-being of all citizens. There is concern that for some people with a disability, unmet oral health needs coupled with the disability could result in medical complications that decrease levels of activity, increase functional dependence and, in turn, increase health-care expenditures. Despite this concern, there has been no systematic national surveillance of oral health among people with disabilities in the U.S.

This article provides much-needed state-by-state and national epidemiologic data regarding oral health among people with disabilities. These data demonstrate a need and provide an opportunity for federal and state programs and other stakeholders to form partnerships to align disability and oral health policy to increase public awareness and allocate resources to improve the oral health of people with disabilities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Vince Campbell, Scott Grosse, Connie Whitehead, Lesley Wolf, and anonymous reviewers from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the Division of Oral Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Public Health Reports for their helpful comments.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville (MD): DHHS, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinmetz E. Current Population Reports, P70-107. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau; 2006. Americans with disabilities: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Healthy people 2010. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Washington: DHHS; 2000. With understanding and improving health and objectives for improving health. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine. Workshop on disability in America: a new look. Washington: National Academy Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health and Human Services (US) National call to action to promote oral health. Rockville (MD): DHHS, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; 2003. NIH Publication No. 03-5303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health and Human Services (US) The Surgeon General's call to action to improve the health and wellness of persons with disabilities. Rockville (MD): DHHS, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Disability Authority. Oral health and disability: the way forward. Dublin (Ireland): National Disability Authority; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mokdad AH, Stroup DF, Giles WH. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Team. Public health surveillance for behavioral risk factors in a changing environment. Recommendations from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Team. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-9):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holtzman D. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. In: Blumenthal DS, DiClemente RJ, editors. Community-based health research: issues and methods. New York: Springer Publishing Co.; 2003. pp. 115–31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.SAS Institute Inc. SAS: Version 9.1. Cary (NC): SAS Institute Inc; 2002–2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN user's manual 8.0. Research Triangle Park (NC): Research Triangle Institute; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age adjustment using the 2000 projected U.S. population. Healthy People 2010 Stat Notes. 2001;20:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phipps KR, Stevens VJ. Relative contribution of caries and periodontal disease in adult tooth loss for an HMO dental population. J Public Health Dent. 1995;55:250–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1995.tb02377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niessen LC, Weyant RJ. Causes of tooth loss in a veteran population. J Public Health Dent. 1989;49:19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1989.tb02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. World Health Organization's international classification of diseases and stomatology, IDC-DA. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loe H. Periodontal disease. The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:329–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu T, Trevisan M, Genco RJ, Falkner KL, Dorn JP, Sempos CT. Examination of the relation between periodontal health status and cardiovascular risk factors: serum total and high density lipoprotein cholesterol, C-reactive protein, and plasma fibrinogen. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:273–82. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andriankaja OM, Genco RJ, Dorn J, Dmochowski J, Hovey K, Falkner KL, et al. The use of different measurements and definitions of periodontal disease in the study of the association between periodontal disease and risk of myocardial infarction. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1067–73. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck JD, Offenbacher S, Williams R, Gibbs P, Garcia R. Periodontitis: a risk factor for coronary heart disease? Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:127–41. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshipura KJ, Rimm EB, Douglass CW, Trichopoulos D, Ascherio A, Willett WC. Poor oral health and coronary heart disease. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1631–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750090301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu TJ, Trevisan M, Genco RJ, Dorn JP, Falkner KL, Sempos CT. Periodontal disease and risk of cerebrovascular disease: a prospective study of a representative sample of US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:290. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joshipura KJ, Hung HC, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Ascherio A. Periodontal disease, tooth loss, and incidence of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:47–52. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000052974.79428.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grodstein F, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ. Post-menopausal hormone use and tooth loss: a prospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:370–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs R, Ghyselen J, Koninckx P, van Steenberghe D. Long-term bone mass evaluation of mandible and lumbar spine in a group of women receiving hormone replacement therapy. Eur J Oral Sci. 1996;104:10–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1996.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeffcoat MK, Chesnut CH., 3rd Systemic osteoporosis and oral bone loss: evidence shows increased risk factors. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;124:49–56. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1993.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sreebny LM, Schwartz SS. A reference guide to drugs and dry mouth. Gerodontology. (2nd ed) 1997;14:33–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.1997.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patrick DL, Bergner M. Measurement of health status in the 1990s. Annu Rev Public Health. 1990;11:165–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.11.050190.001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fiske J, Davis DM, Frances C, Gelbier S. The emotional effects of tooth loss in edentulous people. Br Dent J. 1998;184:90–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809551. discussion 79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthias RE, Atchison KA, Lubben JE, De Jong F, Schweitzer SO. Factors affecting self-ratings of oral health. J Public Health Dent. 1995;55:197–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1995.tb02370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGrath C, Bedi R. A study of the impact of oral health on the quality of life of older people in the UK—findings from a national survey. Gerodontology. 1998;15:93–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.1998.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heffler S, Smith S, Keehan S, Borger C, Clemens MK, Truffer C. U.S. health spending projections for 2004–2014. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;(Suppl) doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.74. Web Exclusives:W5-74-W5-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ship JA, Duffy V, Jones JA, Langmore S. Geriatric oral health and its impact on eating. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:456–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb06419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcus SE, Drury TF, Brown LJ, Zion GR. Tooth retention and tooth loss in the permanent dentition of adults: United States, 1988–1991. J Dent Res. 1996;75(Spec No):684–95. doi: 10.1177/002203459607502S08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keller HH. Malnutrition in institutionalized elderly: how and why? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:1212–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb07305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Idowu AT, Graser GN, Handelman SL. The effect of age and dentition status on masticatory function in older adults. Spec Care Dentist. 1986;6:80–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1986.tb00961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ritchie CS, Joshipura K, Silliman RA, Miller B, Douglas CW. Oral health problems and significant weight loss among community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M366–71. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.7.m366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blaum CS, Fries BE, Fiatarone MA. Factors associated with low body mass index and weight loss in nursing home residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50:M162–8. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.3.m162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sullivan DH, Martin W, Flaxman N, Hagen JE. Oral health problems and involuntary weight loss in a population of frail elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:725–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb07461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]