In recent years, many questions have arisen about the nation's preparedness for a range of disasters, including terrorism, weather-related catastrophes, and biothreats. Particular concern has focused on the ability of the public health and health-care sectors to cope with a large-scale public health emergency such as pandemic influenza.1–3 To bolster their response capabilities, local and state public health officials across the nation have revised and updated many of their emergency operation plans, purchased new equipment, and enhanced their training programs. Many of these changes, however, have gone untested. Often it remains unknown whether public health personnel are appropriately trained in the new plans and procedures; how well new equipment such as communications or surveillance systems will function; or the degree to which these new plans are integrated with the capabilities of other emergency responders, such as law enforcement, fire services, emergency medical services (EMS), emergency management, hospitals, health centers, and others.

Exercises that simulate emergencies have frequently been recommended as a means to improve preparedness.4–9 Broadly speaking, they can significantly help improve preparedness on two levels. At the individual level, exercises present an opportunity to educate personnel on disaster plans and procedures through hands-on practice, while offering constructive critiques of their actions.10,11 On an institutional and/or system-wide level, well-designed exercises can reveal gaps in resources and interagency coordination, uncover planning weaknesses, and clarify specific roles and responsibilities.12–14 While these theoretical benefits of exercises have been noted, few studies have documented the outcomes of such exercises and the specific challenges identified through such efforts.

The Harvard School of Public Health Center for Public Health Preparedness (HSPH-CPHP), established in 2002 and funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under a cooperative agreement with the Association of Schools of Public Health (ASPH), is part of a national network of Academic Centers of Public Health Preparedness (Centers). The Centers are collectively charged with advancing state and local preparedness and response to public health threats. Within this network, HSPH-CPHP has specific responsibility for working with the public health workforce in Massachusetts and Maine to improve preparedness.

Responding to the demands of conducting preparedness exercises voiced by many of our public health partners, HSPH-CPHP launched an exercise program in 2005. In the program, HSPH-CPHP supplies the content expertise relevant to simulating a public health emergency; develops the exercise scenario, Master Scenario Events List (MSEL), and supporting documentation; creates the evaluation plan and instruments; and provides trained personnel to facilitate exercise play and evaluate collective performance.

Since 2005, we have conducted 21 exercises and have direct access to 14 after-action reports (AARs) produced. For this study, we conducted a content analysis of the AARs written following 14 exercises conducted as part of the HSPH-CPHP exercise program, to identify recurrent themes related to the systems challenges faced by the responders during the simulated emergencies. This article describes the most common challenges identified during our exercises, and illustrates how exercises can act as an innovative way for academic partners to collaborate with public health practitioners to improve preparedness.

Articles for From the Schools of Public Health highlight practice- and academic-based activities at the schools. To submit an article, faculty should send a short abstract (50–100 words) via e-mail to Allison Foster, ASPH Deputy Executive Director, at afoster@asph.org.

METHODS

To date, the HSPH-CPHP exercise program has reached more than 3,350 participants from 218 cities and towns at 21 events. Exercises conducted under this program include tabletop (discussion-based), functional (communications-focused), and full-scale exercises. The HSPH-CPHP personnel involved in the exercise program represent expertise in public health, emergency medicine, disaster medicine, prehospital care, hospital administration, and field disaster response. Several of these staff also hold positions within the state public health agency, regional homeland security councils, and regional EMS and hospital consortia. Further, the program is advised by members of the Scientific Advisory Council of the HSPH-CPHP, which includes epidemiologists, infectious disease experts, epidemic modelers, and others.

Each exercise developed by the HSPH-CPHP conforms to the standards of the Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP),15 and is consistent with the principles of the National Incident Management System (NIMS).16 When creating the scenarios, we adhere to the following principles established at the inception of the HSPH-CPHP exercise program, designing exercises that are: (1) focused on response to a specific public health threat; (2) realistic to the greatest extent possible and based on up-to-date knowledge of disease transmission dynamics, preventive measures efficacy, and health outcomes; (3) multidisciplinary and include representatives of public safety (i.e., fire, police, EMS), emergency management, government, and other response agencies whenever possible; (4) regional, involving adjacent municipalities and/or jurisdictions whenever possible; and (5) structured to simultaneously assess and improve performance. Moreover, all exercises are planned in conjunction with local, regional, and state partners, to increase buy-in from key stakeholders and ensure that the event addresses the unique structure and needs of the participating region.

During each exercise, HSPH-CPHP deploys facilitators who moderate participants' discussion to focus on the salient issues, and evaluators who assess and document all communications initiated/received, public information issued, strategic decisions made, and resources requested/deployed. Following the exercise, HSPH-CPHP collects structured feedback from the evaluators, facilitators, and participants. All observations are compared, and any discrepancies are resolved during an evaluator debriefing. Designated HSPH-CPHP personnel then transcribe all observed actions and evaluator comments onto a master integrated timeline to reconstruct all exercise events, and write the AAR. HSPH-CPHP employs an AAR format consistent with HSEEP guidelines,17 including sections detailing the exercise overview, design summary, analysis of capabilities, and recommendations for improvement. AARs are then distributed to the exercise participants, who are expected to create an improvement plan (IP) based upon the comments and proposed action items reported within the AAR.

In this qualitative study, we conducted a content analysis of the 14 AARs authored by HSPH-CPHP. The context was “the public health system response to large-scale emergencies.” The key question and purpose of the analysis was to describe the systems-level challenges faced by the public health system in responding to a large-scale emergency as described in the AARs. The analysis was performed in the following steps.

First, a Modified Delphi identified the most important specific domains that should be considered when evaluating public health agencies' capabilities to respond to a large-scale emergency. Within these domains, we performed a content analysis of the AARs to identify systems-level themes and subthemes within the text. Specifically, key phrases were extracted from the texts that related to the study questions according to the identified domains. The authors discussed how to label subthemes and themes to obtain as distinct descriptions as possible. Themes, subthemes, and supporting quotes were analyzed several times and arranged in a database for further analysis. Finally, the results were organized in a table reporting the frequency of each theme and a description of a selection of subthemes and supporting text quotes.

RESULTS

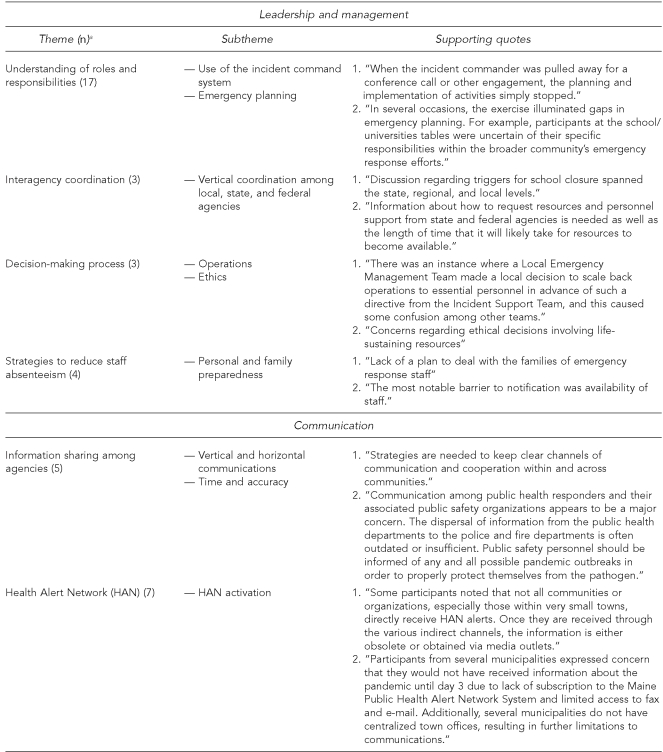

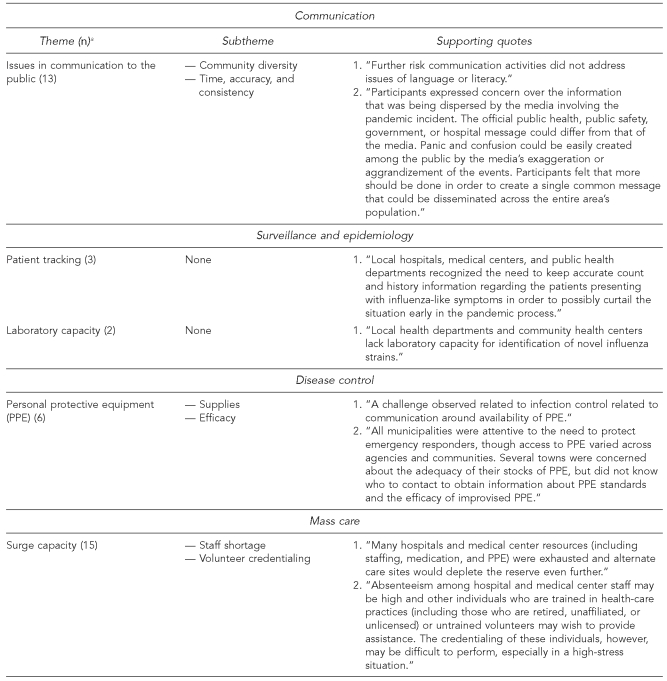

We identified the following domains of emergency response: leadership and management, communication, surveillance and epidemiology, disease control, and mass care. Content analysis of the compendium of AARs then uncovered several categories of recurring systems-level challenges. A detailed description of the themes, subthemes, and supporting text quotes is shown in the Figure. Within the leadership and management domain, four themes were extracted: (1) errors in understanding of individual and agency roles and responsibilities (including insufficient knowledge of the capabilities and assets of responding partners); (2) inconsistent coordination among responders; (3) operational and ethical challenges faced in the decision-making process with significantly limited integration of public health expertise into the response community's decision making; and (4) ability to identify strategies to reduce staff absenteeism.

Figure.

Content analysis results: domains, themes, subthemes, and quotes

Number of times the theme was extracted from the text

Within the communication domain, we identified the following themes: (1) limited communications capabilities, especially with regard to sharing information about health risks among agencies; (2) challenges in communicating health risks to the public; and (3) insufficient activation of the Health Alert Network. Within the surveillance and epidemiology domain, we identified two themes: (1) limited ability to track patients and (2) limited laboratory capacity. Within the disease-control domain, concern about the efficacy and availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) was the most frequent extracted theme. Finally, surge capacity was the main challenge in the mass-care domain.

DISCUSSION

We documented a set of specific systems challenges and improvement items that have consistently emerged from our exercise program and its explicit requirement of multidisciplinary and regional participation. This requirement forces participants to interact with other members of the community who are infrequently seen but critical for effective disaster response. Bringing such responders together to play through a fictional public health emergency pushes communities to identify required tasks not previously considered to be their responsibility, as well as tasks that require greater coordination to provide an effective response.

In some common facets of public health emergency response, such as local community surveillance, epidemiologic investigation, and mass care and/or prophylaxis, we noted that participants often assume that others will perform duties that, according to state emergency plans, are actually their own. Local case investigation during an outbreak is another example. In still other facets of the response—most notably, assessment of health risks, selection of PPE, and risk communication—participants often made key decisions in isolation, without engaging the coordinated assistance and expertise of others in their community or region outside of their own discipline.

These results underscore the growing movement toward complementing community emergency planning with multidisciplinary, regional exercises to improve preparedness. A key lesson that was reinforced is the importance of personal relationships and contacts, as well as explicit face-to-face discussions of the assumptions behind agency-specific plans.

Schools of public health, and the Centers in particular, have much to offer to the community with respect to designing, convening, and hosting such exercises. Universities carry a convening authority that enables them to gather diverse groups from a relatively large surrounding geography. To benefit the community, schools of public health may best be able to assemble regional public health, public safety, municipal government, health-care, and other representatives required to participate. Many schools of public health employ faculty experts in public health threats, preparedness, and exercise design and execution. Some may need to develop expertise in the design, conduct, and evaluation of exercises through HSEEP or other federal training programs, or through partnerships with exercise leaders in local communities. The challenge of financial and logistical support of an exercise program can be addressed through federal or state preparedness programs, private funding, or the direct support of the university in the interest of strengthening connections between academia and public health practice.

A significant challenge in the conduct of public health preparedness exercise is the lack of adequate evaluation materials to assess performance and provide concrete feedback to participants. We have found the HSEEP Exercise Evaluation Guides to be better suited for operations-based exercises than for discussion-based exercises like tabletops, with relatively little of the content of the guides focused on performing public health functions or responding to public health emergencies. This may be because events of operations-based exercises involve responses that are easier to observe and occur in real time, and are therefore more straightforward to evaluate.

Because most public health emergencies occur over a longer time course and over a broader geographic area than traditional public safety emergencies, however, responses to these emergencies are exceptionally difficult to test in an operations-based exercise. As a result, public health emergencies are often simulated in a discussion-based format, such as a tabletop exercise. In this format, the participants' actions are more theoretical and it is more difficult to evaluate their abilities to actually perform the actions they describe. Further, the time course of events during the exercise is generally compressed, with participants discussing days or weeks of events in the course of a few hours of play.

These factors, among others, make accurate and reliable assessment of the participants' performance in discussion-based exercises more challenging. Over the past two years, our evaluation efforts have moved toward process evaluation and validation of instruments to refine the data collected from the exercise program; however, much more is needed to further the science of evaluating preparedness through performance in exercises.

To our knowledge, only nine other published studies have addressed the relationships between exercises and preparedness in public health, and relatively little of the focus has been on identifying methods of evaluating performance. Notably, Dausey and colleagues noted that exercises were useful to identify strengths and weaknesses among the participating agencies, but also recognized that more work is needed to develop more reliable metrics to gauge performance and to assess the impact of postexercise interventions.4 Gebbie and colleagues have made an important step forward in improving exercise evaluation, identifying 46 criteria organized in nine groups to evaluate performance.18 Our study is in agreement with the previous studies in that we find exercises to be useful in identifying systems-level challenges in preparedness. In addition, our analysis adds to this critical field by identifying consistently recurring themes within a set of domains and, therefore, presenting opportunities for intervention. Our study, although qualitative in nature, serves as a foundation for more quantitative analyses in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

Our content analysis of 14 AARs from exercises conducted by the HSPH-CPHP has identified a number of recurrent systems challenges, including: (1) lack of understanding of individual and agency roles and responsibilities, (2) inconsistent coordination among responders, especially among disciplines, (3) limited communications capabilities, especially with regard to sharing information about health risks, (4) significantly limited integration of public health expertise into the response community's decision making, and (5) insufficient knowledge of the capabilities and assets of responding partners. Implementing changes in response to these recurring challenges can advance the iterative cycle of preparedness improvement.

Exercises that simulate public health emergencies can identify specific gaps in planning, resources, and/or assumptions for response that can be addressed and improved before an actual event occurs. Exercises that include representatives from multiple disciplines across a given region provide special benefits to identify specific types of systems-level challenges. Because it is often difficult for local communities to design, convene, execute, and evaluate a multidisciplinary, regional exercise program on their own, schools of public health may consider using their convening authority to do so. Using these lessons to prompt improvements in planning can advance the iterative cycle of preparedness to protect communities in the future.

Footnotes

This activity is supported under a cooperative agreement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), grant number U90/CCU124242-03. The contents of this article do not necessarily reflect the views of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trust for America's Health. Ready or not? Protecting the public's health from diseases, disasters, and bioterrorism. 2005. [cited 2007 Aug 1]. Available from: URL: http://healthyamericans.org/reports/bioterror05/bioterror05Report.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Osterholm MT. Preparing for the next pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1839–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trust for America's Health. Public health laboratories: unprepared and overwhelmed. 2003. [cited 2007 Aug 1]. Available from: URL: http://healthyamericans.org/reports/tfah.

- 4.Dausey DJ, Buehler JW, Lurie N. Designing and conducting tabletop exercises to assess public health preparedness for manmade and naturally occurring biological threats. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett DJ, Everly GS, Jr., Parker CL, Links JM. Applying educational gaming to public health workforce emergency preparedness. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:390–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henning KJ, Brennan PJ, Hoegg C, O'Rourke E, Dyer BD, Grace TL. Health system preparedness for bioterrorism: bringing the tabletop to the hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25:146–55. doi: 10.1086/502366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quiram BJ, Carpender K, Pennel C. The Texas Training Initiative for Emergency Response (T-TIER): an effective learning strategy to prepare the broader audience of health professionals. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005 Nov;(Suppl):S83–9. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200511001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rottman SJ, Shoaf KI, Dorian A. Development of a training curriculum for public health preparedness. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005 Nov;(Suppl):S128–31. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200511001-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uden-Holman T, Walkner L, Huse D, Greene BR, Gentsch D, Atchison CG. Matching documented training needs with practical capacity: lessons learned from Project Public Health Ready. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005 Nov;(Suppl):S106–12. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200511001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke MJ, Sarpy SA, Smith-Crowe K, Chan-Serafin S, Salvador RO, Islam G. Relative effectiveness of worker safety and health training methods. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:315–24. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter J, Livet M, Stewart J, Feigley CE, Scott G, Richter DL. Coastal terrorism: using tabletop discussions to enhance coastal community infrastructure through relationship building. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005 Nov;(Suppl):S45–9. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200511001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livet M, Ritcher J, Ellison L, Dease B, McClure L, Feigley C, et al. Emergency preparedness academy adds public health to readiness equation. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005 Nov;(Suppl):S4–10. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200511001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chi CH, Chao WH, Chuang CC, Tsai MC, Tsai LM. Emergency medical technicians' disaster training by tabletop exercise. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:433–6. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2001.24467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lurie N, Wasserman J, Stoto M, Meyers S, Namkung P, Fielding J, et al. Local variation in public health preparedness: lessons from California. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.341. Jan-Jun; Suppl Web Exclusives:W4-341-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Homeland Security, Office for Domestic Preparedness (US) Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program, volume I: overview and exercise program management. 2007. [cited 2007 Aug 1]. Available from: URL: https://hseep.dhs.gov.

- 16.Department of Homeland Security (US) National Incident Management System. 2004. [cited 2007 Aug 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nims/nims_doc_full.pdf.

- 17.Department of Homeland Security, Office for Domestic Preparedness (US) Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program: after action report/improvement plan. 2004. [cited 2007 Aug 1]. Available from: URL: https://hseep.dhs.gov/support/HSEEP%20AAR-IP%20Template%202007.doc.

- 18.Gebbie KM, Valas J, Merrill J, Morse S. Role of exercises and drills in the evaluation of public health emergency response. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2006;21:173–82. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00003642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]