Abstract

mRNA stability is modulated by elements in the mRNA transcript and their cognate RNA binding proteins. Poly(U) binding protein 1 (Pub1) is a cytoplasmic Saccharomyces cerevisiae mRNA binding protein that stabilizes transcripts containing AU-rich elements (AREs) or stabilizer elements (STEs). In a yeast two-hybrid screen, we identified nuclear poly(A) binding protein 2 (Nab2) as being a Pub1-interacting protein. Nab2 is an essential nucleocytoplasmic shuttling mRNA binding protein that regulates poly(A) tail length and mRNA export. The interaction between Pub1 and Nab2 was confirmed by copurification and in vitro binding assays. The interaction is mediated by the Nab2 zinc finger domain. Analysis of the functional link between these proteins reveals that Nab2, like Pub1, can modulate the stability of specific mRNA transcripts. The half-life of the RPS16B transcript, an ARE-like sequence-containing Pub1 target, is decreased in both nab2-1 and nab2-67 mutants. In contrast, GCN4, an STE-containing Pub1 target, is not affected. Similar results were obtained for other ARE- and STE-containing Pub1 target transcripts. Further analysis reveals that the ARE-like sequence is necessary for Nab2-mediated transcript stabilization. These results suggest that Nab2 functions together with Pub1 to modulate mRNA stability and strengthen a model where nuclear events are coupled to the control of mRNA turnover in the cytoplasm.

The life cycle of an mRNA transcript is comprised of numerous highly coordinated steps, including RNA synthesis, processing, nuclear export, translation, and, ultimately, degradation (40). Although transcription has historically been the most extensively studied step in gene expression, more recent studies have successfully demonstrated that the modulation of expression levels can and does occur at all of these steps in the mRNA life cycle (40). Specifically, mRNA degradation is an important point for this modulation (19, 61). The half-life of an mRNA transcript can change in response to a variety of stimuli including environmental factors, mitogens, growth factors, and hormones (29). Interestingly, transcripts encoding proteins with housekeeping functions are typically characterized by long half-lives, while transcripts encoding proteins that are required transiently, such as during the cell cycle or differentiation, often have shorter half-lives (29). For example, in human cells, the mRNA transcript for the housekeeping glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) has a half-life of over 24 h (34), whereas the mRNA transcript for the transient transcription factor c-myc (10) has a half-life of 10 min (13).

A number of studies that have analyzed mRNA turnover as a mode of regulating gene expression have exploited the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and those studies have uncovered crucial components of evolutionarily conserved mRNA decay mechanisms (28, 56, 61). The half-lives of yeast mRNAs vary substantially from 3 min to >100 min (24, 59), consistent with the idea that mRNA stability is a key regulatory mechanism in this model organism. In fact, certain groups of yeast mRNAs encoding functionally related proteins exhibit similar degradation profiles in response to environmental signals (24), suggesting that mRNA decay is coordinated with the biological requirements of the cell. These observations highlight the significant contribution of mRNA decay to the regulation of gene expression.

Throughout its biogenesis, mRNA is complexed with many RNA binding proteins that associate and dissociate at given times during the maturation of the transcript (14). The interplay between these RNA binding proteins and distinct cis-acting elements in the target mRNA transcripts regulates the mRNA life cycle (14). Significant evidence suggests that such steps are coordinated and mechanistically coupled rather than sequential (57). Some of the mechanisms that couple mRNA synthesis and export (57), and also translation and mRNA degradation (11, 32), have been characterized. However, the mechanistic basis for the coupling between mRNA processing/export and mRNA degradation is less well understood. Some examples of how nuclear events associated with mRNA processing can influence the fate of the mRNA in the cytoplasm have recently come to light. One example is poly(A) binding protein 1 (Pab1), which is localized in the cytoplasm at steady state (50) and is the key factor that controls the poly(A) tail-stimulated pathway for translation initiation and modulates mRNA stability in the cytoplasm (49). However, Pab1 can also shuttle into the nucleus (7, 15), where it can further regulate mRNA 3′-end processing (39) and overall poly(A) tail length (5). How these nuclear functions of Pab1 influence its well-characterized cytoplasmic functions is presently not understood; however, this role may involve interactions with other RNA binding proteins that associate with the transcript in the nucleus. Pab1 is only one of several RNA binding proteins that complex with mRNA transcripts in the nucleus and exert effects in the cytoplasm.

Some RNA binding proteins regulate gene expression by stabilizing or destabilizing particular target mRNAs (60). For example, yeast poly(U) binding protein 1 (Pub1) is a major nuclear and cytoplasmic poly(A) RNA binding protein (2) that has been implicated in the regulation of mRNA turnover (48, 56). HuR, the apparent mammalian orthologue of Pub1 (17, 45), stabilizes AU-rich element (ARE)-containing transcripts by protecting them from degradation via the deadenylation-dependent pathway (17, 41). Similarly, Pub1 binds to and stabilizes ARE and ARE-like sequence-containing transcripts (16). In addition, Pub1 can bind to a stabilizer element (STE) located in the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) of upstream open reading frame (ORF) (uORF)-containing transcripts to prevent their turnover via the nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) pathway (48). As described previously for the poly(A) binding protein Pab1 (7, 15), Pub1 is predominantly cytoplasmic, but it has also been detected in the nucleus (2). At present, it is unclear how Pub1 interfaces with other RNA binding proteins to stabilize target RNA transcripts.

Here, we report the identification of physical and functional interactions between Pub1 and the yeast heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) nuclear poly(A) RNA binding protein 2 (Nab2). Nab2 is an essential, shuttling hnRNP required for both mRNA poly(A) tail length control and poly(A) RNA export (23, 26). Furthermore, we find that Nab2 can also modulate the stability of Pub1 target transcripts that contain ARE-like elements but not those transcripts that contain an STE. We propose a model in which Nab2, acting as a broad mRNA binding protein, could help recruit Pub1 to its specific targets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and chemicals.

Yeast strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Methods for general yeast culture and DNA manipulations were performed according to standard protocols (4). All chemicals were obtained from Sigma, United States Biological, or Fisher unless otherwise noted.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Designation | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | |||

| SVL86 | L40 | (L40) MATahis3 trp1 leu2 ade2 LYS::(lexA op)4-HIS3 URA3::(lexA op)8-lacZ | Clontech |

| SVL129 | L40-41 | (L40-41) MATahis3 trp1 leu2 ade2 LYS::(lexAop)4-HIS3 URA3::(lexA op)8-lacZ [pBTM-NIP7] [pACT-NOP8] | 64 |

| SVL296 | rpb1-1 | MATα ura3 his4 rpb1-1 | 43 |

| SVL316 | EGY48 | MATα trp1 ura3 his3 leu2::lexA-LEU2 [URA3 LacZ] | Invitrogen |

| SVL467 | Pub1-TAP | MATaura3 met15 leu2 PUB1-TAP::HIS3 | Open Biosystems |

| SVL538 | Nab2-TAP | MATaura3 met15 leu2 NAB2-TAP::HIS3 | Open Biosystems |

| SVL544 | Δnab2 | MATaura3 trp1 leu2 nab2::HIS3 [pSV877] | 23 |

| SVL679 | Δnab2 rpb1-1 | MATaura3 trp1 leu2 his3 rpb1-1 nab2::KAN MX4 [pSV877] | This study |

| SVL549 | Δnab2 Δpub1 | MATaura3 trp1 leu2 pub1::KAN MX4 nab2::HIS3 [pSV877] | This study |

| SVL565 | Sec27-TAP | MATaura3 met15 leu2 SEC27-TAP::HIS3 | Open Biosystems |

| SVL678 | Δpub1 rpb1-1 | MATaura3 trp1 leu2 his3 rpb1-1 pub1::KAN MX4 | This study |

| SVL680 | Δpub1, Δupf1 rpb1-1 | MATaura3 trp1 leu2 rpb1-1 pub1::KAN MX4 upf1::HIS3 | This study |

| SVL682 | Δnab2 Δpub1 rpb1-1 | MATaura3 tr1 leu2 rpb1-1 nab2::KAN MX4 upf1::HIS3 [pSV877] | This study |

| SVL688 | rat7-1 rpb1-1 | MATaura3 trp1 leu2 his3 rpb1-1 rat7-1 | This study |

| SVL690 | Δpub1 RPS16B ΔARE rpb1-1 | MATaura3 leu2 his3 rpb1-1 pub1::KAN MX4 RPS16BΔARE-TRP1 | This study |

| SVL691 | Δnab2 RPS16B ΔARE rpb1-1 | MATaura3 leu2 his3 rpb1-1 nab2::KAN MX4 [pSV877] RPS16BΔARE- TRP1 | This study |

| Plasmids | |||

| pSV59 | pRS315 | CEN6 LEU2 | 52 |

| pSV149 | Gal4 AD | pACT; GAL4 AD 2μm LEU2 | Clontech |

| pSV408 | His6-Pub1 | pQE30-PUB1 | This study |

| pSV424 | LexA-Pub1 | pBTM116-PUB1 2μm TRP1 | This study |

| pSV491 | GST-Nab2 | pGEX-4T-NAB2 | This study |

| pSV545 | B42-Pub1 | pJG4-5-PUB1 2μm TRP1 | This study |

| pSV567 | LexA-Nab2 | pEG202-NAB2 2μm HIS3 | 23 |

| pSV568 | LexA-ΔN Nab2 | pEG202-ΔN NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV569 | LexA-ΔRGG Nab2 | pEG202-ΔRGG NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV570 | LexA-ΔQ Nab2 | pEG202-ΔQ NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV571 | LexA-ΔCCCH Nab2 | pEG202-ΔCCCH NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV572 | Nab2 | NAB2 CEN6 LEU2 | 37 |

| pSV575 | ΔN Nab2 | ΔN-NAB2 CEN6 LEU2 | 37 |

| pSV597 | LexA-CCCH Nab2 | pEG202-CCCH NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV607 | GST-ΔCCCH Nab2 | pGEX-4T-ΔCCCH NAB2 | This study |

| pSV609 | GST-CCCH Nab2 | pGEX-4T-CCCH NAB2 | This study |

| pSV645 | LexA-ΔC3 Nab2 | pEG202-ΔC3 NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV646 | LexA-ΔCT Nab2 | pEG202-ΔCT NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV741 | LexA-ΔC4 Nab2 | pEG202-ΔC4-NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV859 | GST-Nab2-67 | pGEX-4T-nab2-67 | This study |

| pSV864 | LexA-CCCH-67 | pEG202-ccch-67 NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV876 | Nab2-67 | nab2-67 CEN6 LEU2 | This study |

| pSV877 | Nab2 | NAB2 CEN6 URA3 | 37 |

| pSV878 | LexA-CCCH-1-4 | pEG202-ccch-14 NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV879 | LexA-CCCH-5-7 | pEG202-ccch-57 NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV880 | LexA-CCCH-1-7 | pEG202-ccch-17 NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV881 | LexA-CCCH-5 | pEG202-ccch-5 NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV882 | LexA-CCCH-6 | pEG202-ccch-6 NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV883 | LexA-CCCH-7 | pEG202-ccch-7 NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

| pSV884 | LexA-CCCH-56 | pEG202-ccch-56 NAB2 2μm HIS3 | This study |

Two-hybrid screen.

The two-hybrid screen was performed using S. cerevisiae strain L40 (SVL86) that harbors the HIS3 and lacZ reporter genes (30). The strain was transformed with the bait plasmid pSV424, encoding an in-frame fusion of the lexA DNA binding domain with the entire coding sequence of PUB1. Expression of the bait protein (LexA-Pub1) in L40 cells was confirmed by immunoblotting using an anti-LexA antibody (Santa Cruz). L40 cells containing the Pub1 bait plasmid were transformed with a yeast cDNA library fused to the Gal4 activation domain (ATCC 87002). Transformants were plated onto selective medium (lacking Leu, Trp, and His) and incubated for 5 days at 30°C. The His-positive transformants were further screened for the formation of blue colonies in the β-galactosidase lift assay with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactopyranoside (X-gal) (58) as a complementary test for interactions. The library plasmids from candidate positive clones were isolated, amplified in Escherichia coli HB101 cells, and retransformed into L40 cells, and assays were repeated for growth on selective medium and for blue colony formation. Plasmid DNA was isolated from positive clones and sequenced to identify the genes encoding the interacting proteins.

In vitro β-galactosidase assay.

The β-galactosidase activity from crude yeast extract was assayed by a protocol adapted from a method described previously by Rose and Botstein (46). Yeast cells were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8 to 1.0 and then disrupted in breaking buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM dithiothreitol, 20% glycerol, 5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) using glass beads and a bead beater. Cell extracts were clarified by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 15 min, and 20 μl of supernatant was added to 900 μl of Z buffer (100 mM Na2HPO4 [pH 7.0], 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol). The final volume was adjusted to 1 ml with breaking buffer, and the mixture was preincubated at 28°C for 5 min. Following the preincubation, 200 μl of ortho-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside solution (4 mg/ml in Z buffer) was added, and the reaction was processed until the solution acquired a pale yellow color. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 500 μl of 1 M Na2CO3, and the OD420 was measured. β-Galactosidase activity was calculated using the function (OD420 × 1.7)/(0.0045 × total protein [mg/ml] × reaction time [min]), where the total protein concentration was determined by using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit. Activity measurements were calculated from at least three independent experiments.

Copurification assay.

Yeast cells expressing a specific tandem affinity purification (TAP)-tagged protein were grown in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium at 30°C to an OD600 of ∼0.6. The culture was centrifuged, and cell pellets were resuspended in IPP150 buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, and 3 μg/ml each of aprotinin, leupeptin, chymostatin, and pepstatin). One volume of glass beads was added to each sample, and cells were lysed using a bead beater. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 16,000 × g and assayed for total protein concentration by using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit. Samples of cell extract containing 3 mg of total protein were incubated with 25 μl of immunoglobulin G (IgG)-conjugated Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) in 1 ml for 2 h at 4°C. When required, the suspension was preincubated with 20 μg of RNase A (Sigma) for 20 min at 25°C. After binding to beads, the unbound fraction was collected, and the beads were washed three times with 1 ml IPP150 buffer. To cleave the protein A domain of TAP-fused proteins and release the proteins from beads, the bead pellet was then incubated with 30 μl of IPP150 buffer containing 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.5 μg of tobacco etch virus protease (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 18°C. Supernatant consisting of material released by tobacco etch virus protease treatment was collected, and equal volumes of samples were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting using an anti-Pub1 antibody that we generated for these studies or anti-glutathione S-transferase (GST) antibody (Sigma) as a control.

Protein purification.

Cell lysate preparation and purification of recombinant proteins were performed as recommended by the resin manufacturer (Amersham Biosciences). GST and GST fusion proteins were purified by affinity chromatography on glutathione-Sepharose. Six-histidine-tagged Pub1 (His6-Pub1) was purified with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-Sepharose. The purified His6-Pub1 was used for the immunization of rabbits to obtain polyclonal antibodies (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

In vitro binding assay.

For in vitro binding assays, 5 μg of GST or GST-fused protein was bound to glutathione-Sepharose in phosphate-buffered saline for 30 min at 25°C. After three washes with 1 ml phosphate-buffered saline, 1 μg His6-Pub1 fusion protein was added to a volume of 1 ml buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.5% Triton X-100) containing 10 μg of RNase A, and the reaction mixtures were incubated for 20 min at 25°C to degrade any contaminating RNA. The reaction mixtures were then incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Unbound fractions were collected, and the beads were washed three times with 1 ml buffer A containing 300 mM NaCl. The bound fraction was eluted by incubation with SDS sample buffer for 5 min at 95°C and separated by 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by immunoblotting with anti-GST (Sigma) or anti-Pub1 antibodies.

FISH.

The intracellular localization of poly(A) RNA was assayed by a fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) protocol adapted from methods described previously (1, 63). NAB2-deleted cells (SVL544), maintained by plasmids carrying either wild-type NAB2 (pSV572) or mutant nab2-1 (deletion of the N-terminal domain) (pSV575) (37), and PUB1-deleted cells (SVL549) were grown in 2% glucose minimal medium to log phase at 25°C. Cells were fixed in 5.2% formaldehyde, digested with zymolyase, and subsequently permeabilized. A digoxigenin-labeled oligo(dT)50 probe coupled with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antidigoxigenin antibody (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) was used to detect poly(A) RNA. DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) was used to stain chromatin and indicate the position of the nucleus.

mRNA decay measurements.

mRNA decay rates were determined by either two-step quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) or Northern blot analysis of strains harboring a temperature-sensitive allele of RNA polymerase II (rpb1-1) (43). Briefly, 50 ml of cells was grown at 25°C to an OD600 of ∼0.6. The cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 50 ml of prewarmed medium (37°C) to shut off transcription. Aliquots of cells were removed at 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 15, and 20 min following the temperature shift and rapidly transferred to ice water, followed by centrifugation and freezing at −80°C. Total RNA was extracted from cells and used for either Northern blot or two-step qRT-PCR analysis. Northern blotting was performed as described previously by Ausubel et al. (4). For qRT-PCR, the High Capacity cDNA Archive kit (Applied Biosystems) was used to generate cDNA from RNA, and amplification reactions were performed with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) using the 7500 Real Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Results were analyzed using 7500 system software v1.3, and data were normalized by the ΔΔCT method (36). PGK1 mRNA, which is not affected by Pub1 (16), was used as a control transcript to normalize all samples. Each experiment was repeated at least three times to obtain an average half-life measurement for each transcript.

RESULTS

Identification of Pub1 binding proteins.

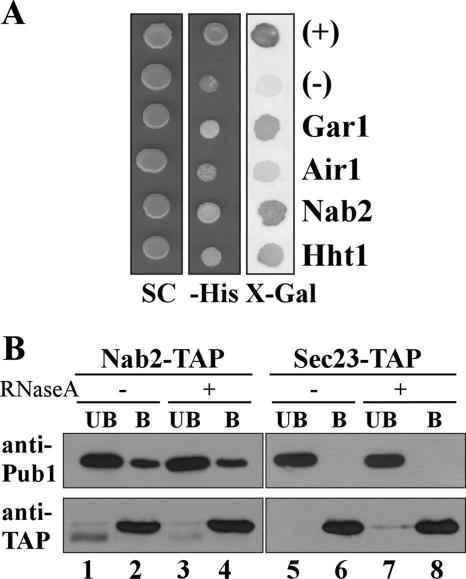

In order to gain insight into how Pub1 cooperates with other proteins to regulate the stability of specific target mRNA transcripts, we sought to identify Pub1-interacting proteins. We employed a yeast two-hybrid system using a LexA-Pub1 fusion protein as bait and an S. cerevisiae cDNA library fused to the GAL4 activation domain (AD) to screen for Pub1-interacting proteins based on their ability to activate the HIS3 and lacZ reporter genes in the presence of LexA-Pub1. The screen led to the identification of several proteins involved in RNA metabolism. As shown in Fig. 1A, where growth on plates lacking His and blue color on plates containing X-gal are indicative of a positive interaction, we identified Gar1, Air1, Nab2, and Hht1 as being putative Pub1 binding partners. Gar1 is a component of the H/ACA snoRNP pseudouridylase complex involved in the modification and cleavage of pre-rRNA (54). Air1 is a zinc knuckle protein component of the TRAMP complex required for the polyadenylation and degradation of a variety of RNA species (9). Hht1 is a core histone required for chromatin assembly and involved in heterochromatin-mediated telomeric and homothallic mating silencing (53). Finally, Nab2 is an essential shuttling hnRNP that is required for correct polyadenylation and poly(A) RNA export from the nucleus (3, 23, 26). The interaction between Pub1 and Nab2 was previously detected in a large-scale two-hybrid study (31).

FIG. 1.

Pub1 binds to proteins involved in RNA metabolism. (A) Yeast two-hybrid strain L40 (Clontech) containing a LexA-Pub1 plasmid (pSV424) was transformed with positive clones from the two-hybrid screen (GAR1, AIR1, NAB2, and HHT1) or with vector pACT (negative control). Transformants and positive control SVL129 cells (64) were grown on control synthetic complete (SC) plates or SC plates lacking histidine (−His) and also assayed for β-galactosidase activity (X-gal). Positive interactions are indicated by growth on plates lacking His and blue color on X-gal plates (darker grey in the right column). (B) Immunoblot analysis of unbound (UB) and bound (B) fractions from the copurification assay using cells expressing Nab2-TAP (lanes 1 to 4) or a control protein, Sec27-TAP (lanes 5 to 8). Proteins were purified with IgG-Sepharose in the presence or absence of 10 μg RNase A, and fractions were probed with an anti-Pub1 antibody (top) or peroxidase antiperoxidase antibody complex (Sigma) (bottom).

Since Nab2 plays an essential role in mRNA metabolism (26) and shows the most robust two-hybrid interaction with Pub1, we decided to focus our efforts on the Pub1-Nab2 association. To confirm and extend the two-hybrid result, a copurification experiment was performed using yeast cells expressing TAP-tagged Nab2. To detect endogenous Pub1, we raised a polyclonal antibody to Pub1 that recognized a band of the predicted size (60 kDa) in wild-type cells but not in Δpub1 cells (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To determine whether Nab2 copurifies with Pub1, yeast lysates from cells producing TAP-tagged Nab2 or Sec27 (negative control) were incubated with IgG-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences), and both the unbound and bound fractions were probed with the anti-Pub1 antibody (Fig. 1B). Immunoblot analysis showed that Nab2-TAP copurifies with Pub1, as indicated by the presence of Pub1 in the bound fraction (Fig. 1B, lane 2). This interaction did not depend on the presence of RNA, as similar results were obtained when lysates were pretreated with RNase A (Fig. 1B, lane 4). Pub1 did not copurify with the control protein Sec27-TAP (Fig. 1B, lanes 6 and 8). Probing with peroxidase antiperoxidase antibody complex confirmed that each TAP-fused protein was produced and bound to beads (Fig. 1B).

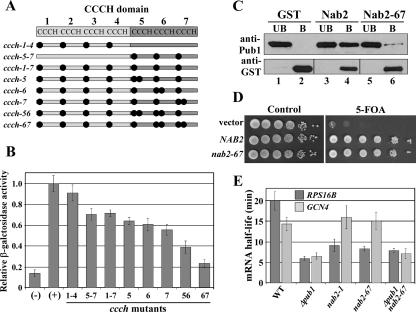

Mapping the Pub1 binding domain of Nab2.

To map the interaction between Nab2 and Pub1, a series of Nab2 variants that precisely delete each of the major predicted domains (Fig. 2A) was generated. These Nab2 variants were expressed from two-hybrid vectors and tested for interactions with Pub1. The expression of all Nab2 variants was confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-Nab2 antibody (data not shown). Results of the binding analysis revealed that the C-terminal zinc finger domain of Nab2 (CCCH) is both necessary and sufficient to bind Pub1 (Fig. 2B). A closer analysis of this domain revealed that the seven CCCH repeats cluster into two groups: a set of four repeats that is followed by a set of three repeats (37). In an attempt to further dissect the Pub1 binding region in the zinc finger domain, we generated Nab2 mutants that deleted the first four repeats (ΔC4), the last three repeats (ΔC3), or the last 47 amino acids (ΔCT) of Nab2, which lie outside of the zinc finger domain (Fig. 2A). Results of this analysis revealed that ΔCT retains binding to Pub1 but that the other deletions within the zinc finger domain abolish the interaction (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that the full zinc finger domain, which is essential for Nab2 function (37), is necessary for Nab2 to retain the conformation required for binding to Pub1.

FIG. 2.

Pub1 binds directly to the zinc finger domain of Nab2. (A) Schematic of Nab2 mutant proteins where the full length (amino acids 1 to 524) is shown at the top and where the four domains within the wild-type protein are indicated by the shading. The amino acids contained within the variant proteins are indicated. (B) Two-hybrid analysis to define the Pub1-interacting domain of Nab2. Two-hybrid SVL316 (EGY48; Invitrogen) cells expressing a transcription activation domain-Pub1 fusion (B42-Pub1; pSV545) transformed with vector (pEG202) (negative control) or plasmids expressing each Nab2 variant were grown on X-gal plates containing galactose to induce the expression of the Pub1 fusion protein. Positive interactions are indicated by the darker grey. (C) GST (lanes 1 and 2), GST-Nab2 (lanes 3 and 4), GST-CCCH (lanes 5 and 6), and GST-Nab2 ΔCCCH (lanes 7 and 8) were purified from E. coli and incubated with recombinant His6-Pub1. The unbound (UB) and bound (B) fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against Pub1 and GST, as described in Materials and Methods. The bottom panel, which shows each of the GST fusion proteins, displays the unbound and bound bands from different areas of the blot due to differences in protein sizes (26 kDa for GST alone, 95 kDa for GST-Nab2, 59 kDa for GST-CCCH, and 62 kDa for GST-ΔCCCH).

The above-described experiment establishes that Pub1 associates with Nab2 via the zinc finger domain of Nab2 but does not address whether this is a direct interaction. To determine whether the interaction is direct, an in vitro binding assay was performed (Fig. 2C). In this experiment, recombinant GST, GST-Nab2, GST-CCCH, or GST-Nab2 ΔCCCH produced in E. coli was bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads and incubated with purified, recombinant His6-Pub1. Results of this experiment show that Pub1 can bind directly both to Nab2 and to the CCCH domain as indicated by the presence of Pub1 in the bound fractions (Fig. 2C, lanes 4 and 6). However, Pub1 did not bind to Nab2 lacking the zinc finger domain (ΔCCCH) or to GST alone (Fig. 2C, lanes 8 and 2, respectively). These results show that Pub1 binds directly to the zinc finger domain of Nab2 in vitro and suggest that Pub1 could interact directly with Nab2 in vivo.

Analysis of the functional interaction between Nab2 and Pub1.

Our experiments link Nab2, an essential mRNA-processing and export factor (23, 26), to Pub1, a nonessential protein that modulates mRNA stability (16, 56). To analyze a possible functional interaction between these proteins, we hypothesized that if cells mutated in both genes show synthetic growth phenotypes, this would suggest that Pub1 may influence the function of the essential Nab2 protein. In contrast, if no synthetic growth phenotype was detected, this could suggest that Nab2 contributes to the nonessential functions mediated by Pub1.

To test for synthetic growth defects, we deleted PUB1 in cells previously deleted for NAB2 but maintained by a plasmid expressing wild-type NAB2. We then combined several Nab2 mutants with the PUB1 deletion by shuffling nab2-1 (ΔN), ΔQQQP, and ΔRGG NAB2 plasmids (37) into the Δpub1 Δnab2 cells. We found that the deletion of PUB1 did not exacerbate the growth defect of any of the Nab2 mutants (data not shown), suggesting that the essential functions of Nab2 are not affected by the deletion of PUB1.

To further probe whether Pub1 affects processes mediated by Nab2, we examined poly(A) RNA localization in Δpub1 cells. In wild-type cells, poly(A) RNA localizes throughout the cell (Fig. 3), while nab2-1 mutant cells show robust nuclear accumulation of poly(A) RNA (Fig. 3) (37). In contrast, Δpub1 cells show no nuclear accumulation of poly(A) RNA (Fig. 3), confirming that Pub1 is not required for poly(A) RNA export. These results lead us to believe that Pub1 does not significantly affect the essential functions of Nab2.

FIG. 3.

Deletion of PUB1 does not cause poly(A) RNA accumulation within the nucleus. PUB1 deletion cells (Δpub1) were grown to log phase and subjected to FISH as described in Materials and Methods. As a control, we also analyzed NAB2 deletion cells (SVL544) expressing either wild-type (WT) NAB2 (pSV572) or the nab2-1 allele (pSV575). Poly(A) RNA was detected using an oligo(dT) probe. The nucleus is indicated by DAPI staining of chromatin, and corresponding differential interference contrast images are shown.

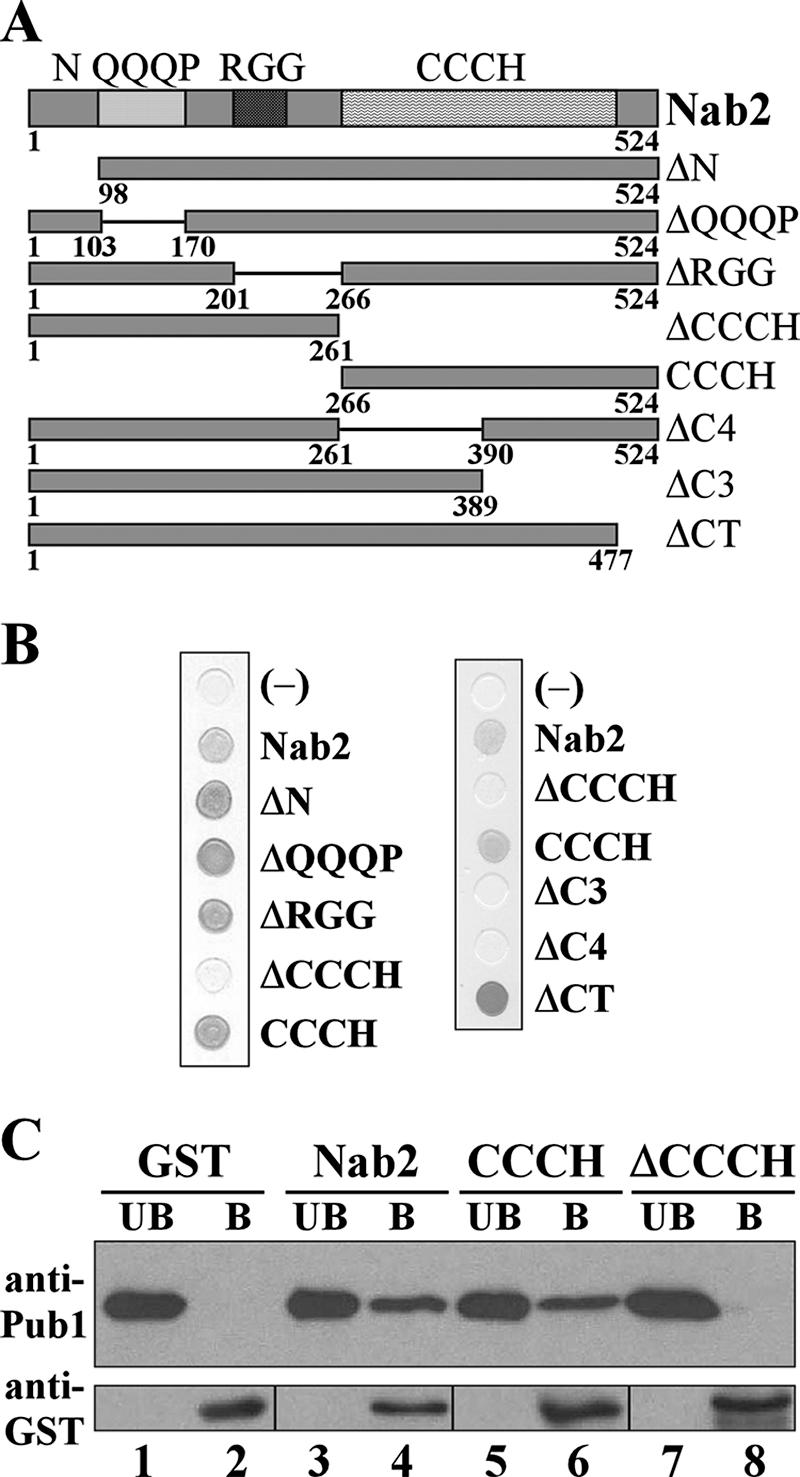

We next tested whether Nab2 can influence mRNA stability, a known cellular function of Pub1 (16, 48, 56). Pub1 can bind to specific ARE-bearing transcripts, leading to their stabilization (56). In addition, Pub1 can selectively bind to STEs of uORF-containing transcripts, preventing their turnover via the NMD pathway (48). We selected two transcripts to analyze in detail, RPS16B and GCN4 (Fig. 4A). The RPS16B mRNA is an ARE-like sequence-containing transcript, while the GCN4 mRNA is an STE-containing transcript (16). Both of these transcripts are bound and stabilized by Pub1 (16, 48). To determine whether Nab2 could modulate mRNA stability, the half-lives of these two mRNA transcripts were determined in nab2-1 mutant cells. We performed at least three independent experiments, as described in Material and Methods, and used the PGK1 transcript as a control for a stable transcript, not affected by Pub1 (16, 56), to calculate an average half-life for each transcript in wild-type, Δpub1, nab2-1, and Δpub1 nab2-1 cells (Table 2). Interestingly, nab2-1 cells showed a decreased half-life of the ARE-like sequence-containing RPS16B transcript compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 4B). As expected, Δpub1 cells also showed a decrease in the half-life of RPS16B (Fig. 4B). The change in the half-life of the RPS16B transcript is comparable to the change previously observed by Duttagupta et al. using the same method (16). The combination of Δpub1 and nab2-1 did not significantly decrease RPS16B mRNA stability compared to Δpub1 alone (Fig. 4B), suggesting that Nab2 and Pub1 stabilize this transcript through the same pathway. In contrast to Δpub1 cells, the stability of the STE-containing GCN4 transcript was not decreased in nab2-1 cells (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Nab2 modulates mRNA stability of an ARE-like sequence-containing transcript. (A) Schematic of the ARE-like sequence-containing RPS16 and STE-containing GCN4 transcripts. (B) The stability of the RPS16B transcript is decreased in nab2-1 cells. Wild-type (WT), Δpub1, nab2-1, Δpub1 nab2-1, and rat7-1 cells harboring a temperature-sensitive allele of RNA polymerase II (rpb1-1) (43) were grown to mid-log phase in YPD medium, and total mRNA was isolated at specific times following the inhibition of transcription by shifting the cells to the nonpermissive temperature. cDNA was prepared from each sample and subjected to qRT-PCR to analyze the RPS16B, GCN4, and PGK1 (stable control) transcripts. Transcript half-lives were calculated by exponential fit, and a P value of <0.05 was considered to be significant. Standard deviations are indicated. (C) Northern blot analysis of decay of the RPS16B transcript. Total mRNA samples isolated after shifting wild-type, Δpub1, and nab2-1 cells harboring the rpb1-1 allele to the nonpermissive temperature were probed for RPS16B and PGK1 transcripts at the times indicated.

TABLE 2.

Half-life of Pub1 mRNA targets

| Strain | Half-life of targeta:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPS16B | GCN4 | RPL17A | RPS24B | WSC3 | |

| Wild type | 19.8 ± 2.1 | 14.4 ± 1.6 | >20 | >20 | 19.4 ± 0.9 |

| Δpub1 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 6.5 ± 0.8 | 7.6 ± 1.2 | 8.1 ± 0.9 | 11.6 ± 3.1 |

| nab2-1 | 9.2 ± 1.5 | 16.0 ± 2.8 | 12.5 ± 0.6 | 14.0 ± 0.4 | >20 |

| Δpub1 nab2-1 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 9.0 ± 1.9 | ND | ND | ND |

| nab2-67 | 8.3 ± 0.5 | 15.1 ± 2.1 | 11.6 ± 0.9 | 15.3 ± 1.1 | >20 |

| Δpub1 nab2-67 | 6.9 ± 0.6 | 7.1 ± 1.2 | ND | ND | ND |

| rat7-1 | 18.7 ± 1.8 | 13.2 ± 1.7 | ND | ND | ND |

| Δpub1 Δupf1 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 13.9 ± 1.4 | ND | ND | ND |

| nab2-1 Δupf1 | 8.5 ± 1.3 | 15.3 ± 2.5 | ND | ND | ND |

| nab2-67 Δupf1 | 9.1 ± 1.2 | 14.5 ± 2.1 | ND | ND | ND |

ND, not determined.

We performed Northern blot analysis to ensure that the real-time PCR method used in our study detects changes in the stability of full-length RPS16B mRNA. Each sample displayed a single specific band in this analysis (Fig. 4C), demonstrating that there is no significant decay intermediate which could confound the mRNA quantification by real-time PCR. Furthermore, the pattern of RPS16B transcript destabilization in both Δpub1 and nab2-1 cells is similar to that observed using the real-time PCR method (Fig. 4C). Finally, we verified that PGK1 transcript stability is not altered in wild-type, Δpub1, or nab2-1 cells, confirming that this transcript is an appropriate endogenous control.

The decreased stability of the ARE-like sequence-containing RPS16B transcript could be a secondary effect of mRNA accumulation within the nucleus since nab2-1 cells show nuclear accumulation of poly(A) RNA (Fig. 3) (37). This scenario seems unlikely since the stability of both the control PGK1 and the GCN4 transcripts was not decreased in the nab2-1 mutant cells. However, to eliminate this possibility, we examined the half-life of the RPS16B and GCN4 transcripts in rat7-1 cells, which express a variant of the Nup159 nuclear pore protein that causes nuclear accumulation of poly(A) RNA at the nonpermissive temperature (22). We observed only a small and not statistically significant decrease in the half-lives of the transcripts analyzed in this mutant (Fig. 4B and Table 2), suggesting that the decreased stability of ARE-like sequence-containing transcripts in the nab2-1 mutant is not merely a secondary effect of the nuclear accumulation of poly(A) RNA.

Identification of a new NAB2 mutant.

The physical interaction between Pub1 and Nab2 as well as the specific RNA instability revealed in the nab2-1 mutant suggest a role for Nab2 in the Pub1-mediated regulation of mRNA stability. However, there was no direct correlation between these two facts, as the nab2-1 mutant lacks the N-terminal portion of Nab2 (37), which is a domain of Nab2 that is not necessary for its interaction with Pub1 (Fig. 2B). In order to obtain a NAB2 variant that no longer interacts with Pub1, we performed site-directed mutagenesis of the Nab2 CCCH domain. As described above, this domain is composed of seven CCCH repeats clustered into two groups, a set of four repeats and a set of three repeats, all apparently necessary for the interaction with Pub1 (Fig. 2B). The first cysteine of each CCCH repeat was cumulatively replaced with arginine, generating three different CCCH mutants: ccch-1-4, with substitutions of Cys to Arg in all four CCCH repeats of the first set of zinc fingers; ccch-5-7, with substitutions of Cys to Arg in all three CCCH repeats of the second set of zinc finger; and ccch-1-7, with substitutions of Cys to Arg in all seven CCCH repeats (Fig. 5A). All amino acid substitutions are detailed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Amino acid residue substitutions in the first CCCH mutant (ccch-1-4) did not cause any decrease in the interaction of Nab2 with Pub1 as assessed by two-hybrid assay (Fig. 5B). However, a slight but significant decrease was observed when substitutions were introduced into the second set of zinc fingers (ccch-5-7 and ccch-1-7) (Fig. 5B). We then created additional amino acid substitutions in the ccch-1-7 mutant, resulting in the substitution of the second cysteine of the fifth (ccch-5), sixth (ccch-6), and seventh (ccch-7) CCCH repeats with arginine, and combined substitutions of the second cysteine to arginine within the fifth and sixth (ccch-56) or the sixth and seventh (ccch-67) CCCH repeats (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5B, the substitution of both cysteine residues of adjacent zinc fingers (ccch-56 and ccch-67) causes a dramatic decrease in the interaction between the Nab2 zinc finger domain and Pub1. All CCCH mutants showed approximately the same expression as the wild-type CCCH domain as assessed by immunoblotting (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Amino acid substitutions within the Nab2 zinc finger domain abolish the interaction with Pub1 and decrease RPS16B mRNA stability. (A) Schematic of amino acid changes within the Nab2 CCCH domain. The specific amino acid residues changed in each Nab2 variant are detailed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. (B) Amino acid substitutions in the Nab2 CCCH domain decrease binding to Pub1. Two-hybrid SVL316 (EGY48; Invitrogen) cells expressing a transcription activation domain-Pub1 fusion (B42-Pub1; pSV545) were transformed with vector (pEG202) (-) or plasmids expressing wild-type (+) or the indicated variant CCCH Nab2 domains. Cells were grown in liquid medium containing galactose, and quantification of lacZ reporter activity, as a measure of the Pub1 interaction with the CCCH domain of Nab2, was determined by an in vitro β-galactosidase assay. The bar graph displays β-galactosidase activity relative to the wild-type CCCH domain, which was set to 1.0. Standard deviations in the data are indicated. (C) Nab2-67 shows a greatly decreased interaction with Pub1. GST (lanes 1 and 2), GST-Nab2 (lanes 3 and 4), or GST-Nab2-67 (lanes 5 and 6) was purified from E. coli and incubated with recombinant His6-Pub1. The unbound (UB) and bound (B) fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Pub1 and anti-GST antibodies. The bottom panel corresponds to the unbound and bound bands from different areas in the blot due to differences in protein sizes (26 kDa for GST alone and 95 kDa for GST-Nab2). (D) The nab2-67 mutant allele is functional. A plasmid shuffle technique was used to assess the ability of the nab2-67 mutant to replace the essential function of NAB2. NAB2 deletion cells (SVL544) maintained by a URA3 NAB2 plasmid (pSV877) were transformed with test plasmids carrying vector alone (pSV59), wild-type NAB2 (pSV572), or nab2-67 (pSV876). Samples were serially diluted and spotted onto a control plate (SC medium lacking Ura), where the wild-type NAB2 plasmid is retained, or selective medium (5-fluoroorotic acid [5-FOA]), where the wild-type NAB2 plasmid is lost and the only cellular copy of the essential NAB2 gene is provided by the test plasmid. Plates were incubated for 3 days at 30°C. Vector alone and wild-type NAB2 served as the negative and positive growth controls. (E) The stability of the RPS16B transcript is decreased in nab2-67 cells compared to wild-type (WT) cells. The half-lives of the RPS16B and GCN4 transcripts were determined using qRT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods.

To assess the consequences of disrupting the interaction between Nab2 and Pub1, we introduced the ccch-67 amino acid substitutions into the full-length Nab2 protein. To assay the interaction between the Nab2-67 mutant protein and Pub1, we performed an in vitro binding assay using recombinant GST, GST-Nab2, or GST-Nab2-67 bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads and purified His6-Pub1. We found that the interaction between Nab2-67 and Pub1 was almost abolished (Fig. 5C, lane 6) compared to the interaction between wild-type Nab2 and Pub1 (Fig. 5C, lane 4), confirming the results obtained by yeast two-hybrid analysis. A plasmid shuffle assay was then used to assess the function of the nab2-67 allele (Fig. 5D). The positive control for growth is wild-type NAB2, and the negative control is the vector alone. Cells expressing nab2-67 as the sole copy of NAB2 showed no apparent growth defect at 30°C (Fig. 5D), indicating that this mutant can replace the essential function of the Nab2 protein. The same result was obtained when cells were grown at 14°C or 37°C (data not shown), demonstrating that nab2-67 mutant cells do not display a temperature-sensitive phenotype. Finally, we tested whether the nab2-67 mutant affects the stability of Pub1 target transcripts. The stability of both the RPS16B and GCN4 transcripts was determined in nab2-67 cells. As described above for nab2-1 (Fig. 4B), the nab2-67 mutant cells showed a decrease in the half-life of the RPS16B transcript, but the stability of the GCN4 transcript was not altered in these cells (Fig. 5E and Table 2). Moreover, the combination of Δpub1 and nab2-67 did not significantly change RPS16B mRNA stability compared to Δpub1 alone (Fig. 5E and Table 2). To test the generality of these results, we analyzed the stability of two additional ARE-like sequence-containing transcripts, RPL17A and RPS24B, and one additional STE-containing transcript, WSC3 (16). Consistent with the RPS16B results, both the RPL17A and RPS24B transcripts were less stable in nab2-1 and nab2-67 cells than in wild-type cells (Table 2). In contrast, the stability of the STE-containing transcript WSC3 (16), like GCN4, was not decreased in either nab2-1 or nab2-67 mutant cells (Table 2). Thus, as observed for two different NAB2 mutants (nab2-1 and nab2-67), our results indicate that the Nab2 protein affects the stability of ARE-like-sequence-containing transcripts but not transcripts containing an STE.

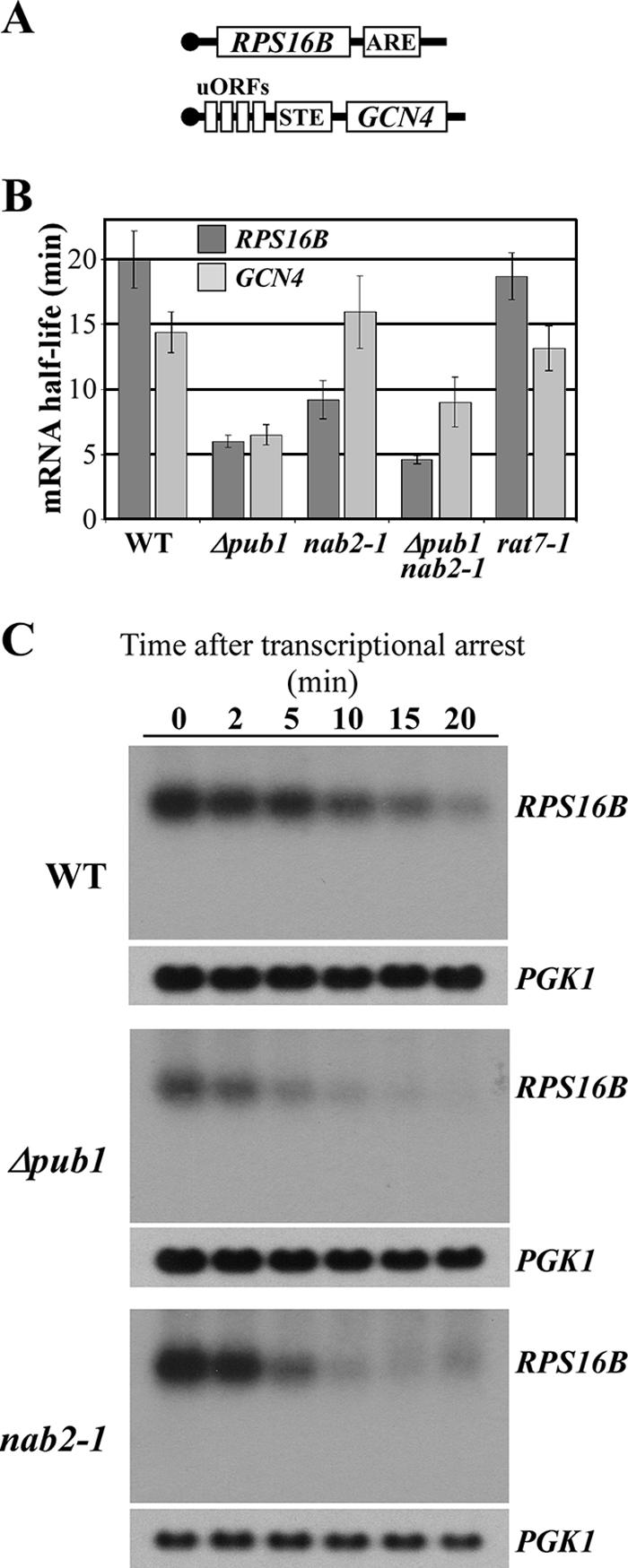

Stabilization of the RPS16B transcript by Nab2 is dependent on the ARE-like sequence.

To test whether the RPS16B mRNA stability mediated by Nab2 is dependent on the ARE-like sequence, the half-life of an RPS16B mutant transcript lacking 16 nucleotides corresponding to its ARE-like sequence (RPS16B-ΔARE) was determined using NAB2 mutants. The RPS16B-ΔARE mutant was generated by overlap PCR and cloned into an integrative vector. As shown in the schematic in Fig. 6A, the plasmid was integrated into the genome of both Δpub1 cells and Δnab2 cells maintained by a wild-type NAB2 plasmid. This integration strategy resulted in gene duplication at the RPS16B locus such that cells express both the ARE-deleted transcript and the endogenous RPS16B transcript (Fig. 6A). With this experimental design, we could simultaneously measure the half-lives of both the control RPS16B transcript and the RPS16B-ΔARE transcript from the same cells by designing different real-time PCR reverse primers. A primer hybridizing in the ARE-like sequence (Fig. 6A) was used to amplify the endogenous RPS16B cDNA. A primer hybridizing to the junction created by deletion of the ARE element (Fig. 6A) was used to specifically amplify the RPS16B-ΔARE cDNA (Fig. 6A). Both reverse primers were paired with the same forward primer (F). To analyze the effect of Nab2 on the stability of both the endogenous RPS16B transcript and the RPS16B-ΔARE transcript, the wild-type NAB2 plasmid covering the Δnab2 cells was replaced by a LEU plasmid containing NAB2, nab2-1, or nab2-67 (Fig. 6B) through a standard plasmid shuffle. As described above, the RPS16B transcript was less stable in Δpub1, nab2-1, and nab2-67 cells than in wild-type cells (Fig. 6B and Table 2). In contrast, the stability of the RPS16B-ΔARE mRNA was comparable in wild-type, Δpub1, nab2-1, and nab2-67 cells (Fig. 6B and Table 3). These results demonstrate that the ARE-like sequence is necessary for RPS16B transcript destabilization in both nab2 mutants. Importantly, these data provide a link between mRNA stabilization mediated by Nab2 and the requirement for an ARE-like sequence, which is a binding site for Pub1 (16).

FIG. 6.

Stabilization of RPS16B by Nab2 is dependent on the presence of the ARE-like sequence. (A) Schematic of integration at the RPS16B locus demonstrating how the integration of RPS16B-ΔARE was accomplished. The location of the primer pairs used to simultaneously amplify both endogenous RPS16B and RPS16B-ΔARE by qRT-PCR is also indicated. The F primer, which is used to amplify both endogenous RPS16B and the integrated RPS16B-ΔARE allele, hybridizes within the ORF region of both RPS16B sequences. The R primer, which specifically amplifies endogenous RPS16B, hybridizes with the ARE element. The R′ primer, which specifically amplifies RPS16B-ΔARE, hybridizes to the junction created by the deletion of the ARE element. (B) The half-lives of both the RPS16B and RPS16B-ΔARE transcripts were simultaneously determined in wild-type (WT), Δpub1, nab2-1, and nab2-67 cells harboring the rpb1-1 allele. Cells were grown to mid-log phase in YPD medium and shifted to the nonpermissive temperature for 0, 2, 5, 10, 15, and 20 min. Total mRNA was isolated from each sample, reverse transcribed to cDNA, and subjected to qRT-PCR to determine RPS16B, RPS16B-ΔARE, and PGK1 (control) transcript half-lives. Standard deviations in the data are indicated.

TABLE 3.

Half-lives of RPS16B and RPS16B-ΔARE transcripts in NAB2 mutants

| Strain | Half-life of target:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| RPS16B | RPS16B-ΔARE | |

| Wild type | 19.3 ± 2.7 | >20 |

| Δpub1 | 6.5 ± 1.2 | >20 |

| nab2-1 | 9.5 ± 1.1 | 18.5 ± 2.3 |

| nab2-67 | 7.9 ± 0.7 | >20 |

Decay of the ARE-like sequence-containing RPS16B transcript is not NMD dependent.

Pub1 modulates mRNA stability by protecting transcripts from different decay pathways (48, 56). Based on a previous analysis of two endogenous yeast transcripts, GCN4 and YAP1, it was suggested that STE-containing mRNAs are degraded via NMD because the stop codon of the upstream ORF is recognized as a premature stop codon (48). We found that the stability of the ARE-like sequence-containing transcript RPS16B is dependent on both Pub1 and Nab2, but it is not clear what mechanism leads to the degradation of endogenous ARE-like sequence-containing transcripts or whether Pub1 and Nab2 protect transcripts from the same degradation pathway. To directly test whether the ARE-like transcript that is modulated by Pub1 and Nab2 is degraded by the NMD pathway, we tested whether the deletion of UPF1, which encodes an essential component of the NMD pathway (20), could restore the stability of the RPS16B transcript, which is decreased in Δpub1, nab2-1, and nab2-67 mutant cells. The disruption of the NMD pathway (Δupf1) did not rescue the stability of the RPS16B transcript in Δpub1 Δupf1, nab2-1 Δupf1, or nab2-67 Δupf1 cells, although, as previously reported (48), the deletion of UPF1 did rescue the stability of the STE-containing GCN4 transcript in Δpub1 Δupf1 cells (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The interplay between RNA binding proteins and cis-acting regulatory elements within specific mRNA transcripts can regulate gene expression by stabilizing or destabilizing a particular transcript. Pub1 has been implicated in the stabilization of a group of mRNAs through binding to specific sequences in either the 5′- or 3′-UTR and thereby inhibiting different decay pathways (48, 56). In this report, we demonstrate that the poly(A) RNA binding protein Nab2 can bind directly to Pub1 and can also modulate the stability of a subset of Pub1 target mRNAs.

Since Pub1 is an mRNA binding protein and since we found that it can bind to Nab2, another RNA binding protein, we needed to determine if this interaction could be mediated by RNA. This point is particularly important because the essential CCCH domain on Nab2 that mediates binding to Pub1 has also been implicated in RNA binding (3, 37). We found that TAP-tagged Nab2 copurifies with Pub1 from yeast extract even when the lysate is pretreated with RNase A, suggesting that this interaction is not mediated by RNA. An in vitro binding assay confirmed that Pub1 can bind directly to Nab2 and showed that the zinc finger domain of Nab2 is both necessary and sufficient to directly interact with Pub1.

Classical zinc finger proteins often employ multiple zinc fingers to bind to nucleic acids (38). Typically, aromatic residues within the zinc fingers interact with the nucleic acid to impart sequence specificity (38). However, in addition to binding to nucleic acids, zinc fingers can also bind to proteins (35). Furthermore, there are a number of proteins that contain multiple zinc fingers that mediate distinct binding interactions. For example, the transcription factor TFIIIA, a dual RNA/DNA binding protein, contains nine zinc fingers, and individual zinc fingers are used to recognize both RNA and DNA targets (6, 18, 44, 51). In addition, the transcription factor GATA-1 contains two zinc finger repeats, which not only act as the primary determinant of binding specificity for the DNA sequence GATA but also can mediate protein-protein interactions (38). Similarly, our results suggest that the CCCH domain of Nab2, which contains seven zinc fingers, is a multitasking zinc finger domain required for both RNA-protein and protein-protein interactions.

Previously characterized Pub1 target mRNAs contain two distinct cis-acting elements, the 5′-UTR STE or the 3′-UTR ARE (48, 56). A recent genome-wide survey identified a number of novel ARE-like and A-rich Pub1 binding motifs (16). We found that nab2-1 cells show altered stability of the ARE-like Pub1 target transcripts but no effect on STE-containing Pub1 targets. It is not yet clear whether the effect on the stability of ARE transcripts is a consequence of the nuclear role of Nab2 or whether it reflects a distinct function for Nab2 in the cytoplasm. Given that the poly(A) RNA transcripts in nab2-1 mutant cells accumulate longer poly(A) tails than in wild-type cells (26), it might be logical to assume that the mRNA half-life would be increased in nab2-1 cells. Instead, we found that target RNAs containing an ARE-like element have decreased stability in nab2-1 cells. Although this mutant does interact with Pub1, we suggest that the deletion of the Nab2 N terminus could impact Nab2 function in mRNA stabilization by affecting its interaction with another component of a multifunctional protein complex involved in mRNA export and/or mRNA decay. Consistent with this idea, the same defect in mRNA stability displayed by nab2-1 mutant cells was observed in the novel NAB2 mutant, nab2-67, which encodes a Nab2 variant with a substantially decreased interaction with Pub1 (Fig. 5C).

Based on our results with the nab2-67 mutant, we suggest that the Nab2 function in stabilizing ARE-like sequence-containing transcripts is related to its interaction to Pub1, which acts by modulating the stability of this class of transcripts (16). Consistent with an independent role for Nab2 in modulating mRNA stability through interactions with Pub1, we find that cells expressing the Nab2 mutant nab2-67, which shows a decreased interaction with Pub1, do not display severe growth defects. However, these cells do show an altered stability of a subset of Pub1 target transcripts. These phenotypes for the nab2-67 allele are identical to the phenotypes, no growth defect and altered transcript stability, observed for cells lacking Pub1, strengthening the argument for a functional interaction between Nab2 and Pub1.

We propose that the specific effect of Nab2 on the ARE-like sequence-containing transcripts but not on the STE-containing transcripts could be due to the proximity of the Pub1 binding site, the ARE-like sequence within the 3′-UTR, to the poly(A) tail, which is where Nab2 associates with the transcript (25, 26; S. M. Kelly et al., unpublished data). Consistent with this idea, an interaction between the human poly(A) binding protein PABP and HuR, the apparent human Pub1 orthologue (45, 56), was recently described (42). This interaction increased the stability of the ARE-containing β-casein mRNA transcript through the interaction of the poly(A) tail and the ARE element (42), supporting the idea that these cis-acting elements could work together. In contrast, the STE is located in the 5′-UTR of the GCN4 transcript, a site that should be physically distant from the poly(A) tail and thus not in close physical proximity to Nab2.

Although Nab2 is localized to the nucleus at steady state (3), it shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (23). Likewise, Pub1, which is primarily localized to the cytoplasm, can be detected in the nucleus (2). Recently, evidence has emerged that a number of RNA binding proteins play distinct roles in the nucleus and the cytoplasm (18, 21, 33, 62). For example, Hrp1 is an hnRNP which localizes to the nucleus at steady state (27), where it is required for proper mRNA 3′-end formation (33, 55). However, it can also shuttle to the cytoplasm, where it modulates the NMD pathway (21). Other examples include Gbp2 and Hrb1, which bind to mRNA in the nucleus but are also associated with polysomes in the cytoplasm (62). Additionally, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4AIII, a nuclear protein that is loaded onto the mRNA during splicing in the nucleus, also functions in NMD and has properties related to the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A translation initiation factor (8, 18, 44, 51).

It is still not clear how Pub1 stabilizes transcripts containing 5′-UTR STE or 3′-UTR ARE elements. The NMD pathway is required for the degradation of upstream ORF-containing transcripts that contain the cis-acting STE element (47). In yeast, the major decay pathway for NMD involves 5′ decapping followed by 5′-3′ degradation bypassing deadenylation (12). Previous work showed that the endogenous uORF-containing GCN4 transcript is protected from NMD-mediated decay by the binding of Pub1 to the STE sequence located in the 5′-UTR (48). In the case of ARE-containing transcripts, Pub1 protects a hybrid transcript harboring the tumor necrosis factor alpha ARE from decay via the deadenylation-dependent pathway (56). However, it is not clear whether endogenous ARE-containing transcripts are degraded by the same mechanism. Our results indicate that the stability of the RPS16B transcript is not recovered in Δpub1, nab2-1, or nab2-67 cells where the NMD pathway is impaired by the deletion of UPF1. This result confirms that both Pub1 and Nab2 stabilize the ARE-like sequence-containing transcripts by modulating a pathway that is distinct from NMD.

Pub1 modulates RPS16B mRNA decay through a direct interaction with an ARE-like sequence at the transcript 3′-UTR (16). Our results indicate that the ARE-like sequence in RPS16B mRNA is also necessary for the stabilization mediated by Nab2. The functional association of Nab2 with this specific cis-acting mRNA element could help to coordinate different events involved in the control of gene expression, coupling the maturation and nuclear export steps of mRNA biogenesis to the mRNA decay machinery. Taken together, our study suggests that Nab2, a protein with defined nuclear functions, together with Pub1, plays a role in determining the cytoplasmic fate of some mRNA transcripts, adding Nab2 to a growing list of nuclear RNA binding proteins that modulate the destiny of mRNA transcripts in the cytoplasm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. C. Oliveira for the generous gift of two-hybrid reagents. We also thank M. B. Fasken and S. C. Kerr for comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to members of the Valentini and Corbett laboratories for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants to S.R.V. from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico and to A.H.C. from the National Institutes of Health. L.H.A. was a recipient of Ph.D. fellowships from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 July 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amberg, D. C., A. L. Goldstein, and C. N. Cole. 1992. Isolation and characterization of RAT1: an essential gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae required for the efficient nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of mRNA. Genes Dev. 6:1173-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, J. T., M. R. Paddy, and M. S. Swanson. 1993. PUB1 is a major nuclear and cytoplasmic polyadenylated RNA-binding protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:6102-6113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, J. T., S. M. Wilson, K. V. Datar, and M. S. Swanson. 1993. NAB2: a yeast nuclear polyadenylated RNA-binding protein essential for cell viability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:2730-2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 2001. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

- 5.Brown, C. E., and A. B. Sachs. 1998. Poly(A) tail length control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae occurs by message-specific deadenylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:6548-6559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, R. S. 2005. Zinc finger proteins: getting a grip on RNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15:94-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brune, C., S. E. Munchel, N. Fischer, A. V. Podtelejnikov, and K. Weis. 2005. Yeast poly(A)-binding protein Pab1 shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and functions in mRNA export. RNA 11:517-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan, C. C., J. Dostie, M. D. Diem, W. Feng, M. Mann, J. Rappsilber, and G. Dreyfuss. 2004. eIF4A3 is a novel component of the exon junction complex. RNA 10:200-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chanfreau, G. F. 2005. CUTting genetic noise by polyadenylation-induced RNA degradation. Trends Cell Biol. 15:635-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole, M. D., and S. B. McMahon. 1999. The Myc oncoprotein: a critical evaluation of transactivation and target gene regulation. Oncogene 18:2916-2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coller, J., and R. Parker. 2004. Eukaryotic mRNA decapping. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73:861-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conti, E., and E. Izaurralde. 2005. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: molecular insights and mechanistic variations across species. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17:316-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dani, C., J. M. Blanchard, M. Piechaczyk, S. El Sabouty, L. Marty, and P. Jeanteur. 1984. Extreme instability of myc mRNA in normal and transformed human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:7046-7050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dreyfuss, G., V. N. Kim, and N. Kataoka. 2002. Messenger-RNA-binding proteins and the messages they carry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:195-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn, E. F., C. M. Hammell, C. A. Hodge, and C. N. Cole. 2005. Yeast poly(A)-binding protein, Pab1, and PAN, a poly(A) nuclease complex recruited by Pab1, connect mRNA biogenesis to export. Genes Dev. 19:90-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duttagupta, R., B. Tian, C. J. Wilusz, D. T. Khounh, P. Soteropoulos, M. Ouyang, J. P. Dougherty, and S. W. Peltz. 2005. Global analysis of Pub1p targets reveals a coordinate control of gene expression through modulation of binding and stability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:5499-5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan, X. C., and J. A. Steitz. 1998. Overexpression of HuR, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling protein, increases the in vivo stability of ARE-containing mRNAs. EMBO J. 17:3448-3460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferraiuolo, M. A., C. S. Lee, L. W. Ler, J. L. Hsu, M. Costa-Mattioli, M. J. Luo, R. Reed, and N. Sonenberg. 2004. A nuclear translation-like factor eIF4AIII is recruited to the mRNA during splicing and functions in nonsense-mediated decay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:4118-4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garneau, N. L., J. Wilusz, and C. J. Wilusz. 2007. The highways and byways of mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:113-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez, C. I., A. Bhattacharya, W. Wang, and S. W. Peltz. 2001. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 274:15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez, C. I., M. J. Ruiz-Echevarria, S. Vasudevan, M. F. Henry, and S. W. Peltz. 2000. The yeast hnRNP-like protein Hrp1/Nab4 marks a transcript for nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Mol. Cell 5:489-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorsch, L. C., T. C. Dockendorff, and C. N. Cole. 1995. A conditional allele of the novel repeat-containing yeast nucleoporin RAT7/NUP159 causes both rapid cessation of mRNA export and reversible clustering of nuclear pore complexes. J. Cell Biol. 129:939-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green, D. M., K. A. Marfatia, E. B. Crafton, X. Zhang, X. Cheng, and A. H. Corbett. 2002. Nab2p is required for poly(A) RNA export in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and is regulated by arginine methylation via Hmt1p. J. Biol. Chem. 277:7752-7760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grigull, J., S. Mnaimneh, J. Pootoolal, M. D. Robinson, and T. R. Hughes. 2004. Genome-wide analysis of mRNA stability using transcription inhibitors and microarrays reveals posttranscriptional control of ribosome biogenesis factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:5534-5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guisbert, K., K. Duncan, H. Li, and C. Guthrie. 2005. Functional specificity of shuttling hnRNPs revealed by genome-wide analysis of their RNA binding profiles. RNA 11:383-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hector, R. E., K. R. Nykamp, S. Dheur, J. T. Anderson, P. J. Non, C. R. Urbinati, S. M. Wilson, L. Minvielle-Sebastia, and M. S. Swanson. 2002. Dual requirement for yeast hnRNP Nab2p in mRNA poly(A) tail length control and nuclear export. EMBO J. 21:1800-1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henry, M., C. Z. Borland, M. Bossie, and P. A. Silver. 1996. Potential RNA binding proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identified as suppressors of temperature-sensitive mutations in NPL3. Genetics 142:103-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hilleren, P., and R. Parker. 1999. Mechanisms of mRNA surveillance in eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 33:229-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollams, E. M., K. M. Giles, A. M. Thomson, and P. J. Leedman. 2002. mRNA stability and the control of gene expression: implications for human disease. Neurochem. Res. 27:957-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollenberg, S. M., R. Sternglanz, P. F. Cheng, and H. Weintraub. 1995. Identification of a new family of tissue-specific basic helix-loop-helix proteins with a two-hybrid system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:3813-3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ito, T., T. Chiba, R. Ozawa, M. Yoshida, M. Hattori, and Y. Sakaki. 2001. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4569-4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobson, A., and S. W. Peltz. 1996. Interrelationships of the pathways of mRNA decay and translation in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65:693-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler, M. M., M. F. Henry, E. Shen, J. Zhao, S. Gross, P. A. Silver, and C. L. Moore. 1997. Hrp1, a sequence-specific RNA-binding protein that shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, is required for mRNA 3′-end formation in yeast. Genes Dev. 11:2545-2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lekas, P., K. L. Tin, C. Lee, and R. D. Prokipcak. 2000. The human cytochrome P450 1A1 mRNA is rapidly degraded in HepG2 cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 384:311-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leon, O., and M. Roth. 2000. Zinc fingers: DNA binding and protein-protein interactions. Biol. Res. 33:21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−delta delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marfatia, K. A., E. B. Crafton, D. M. Green, and A. H. Corbett. 2003. Domain analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein, Nab2p. Dissecting the requirements for Nab2p-facilitated poly(A) RNA export. J. Biol. Chem. 278:6731-6740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matthews, J. M., and M. Sunde. 2002. Zinc fingers—folds for many occasions. IUBMB Life 54:351-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minvielle-Sebastia, L., P. J. Preker, T. Wiederkehr, Y. Strahm, and W. Keller. 1997. The major yeast poly(A)-binding protein is associated with cleavage factor IA and functions in premessenger RNA 3′-end formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:7897-7902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore, M. J. 2005. From birth to death: the complex lives of eukaryotic mRNAs. Science 309:1514-1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myer, V. E., X. C. Fan, and J. A. Steitz. 1997. Identification of HuR as a protein implicated in AUUUA-mediated mRNA decay. EMBO J. 16:2130-2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagaoka, K., T. Suzuki, T. Kawano, K. Imakawa, and S. Sakai. 2006. Stability of casein mRNA is ensured by structural interactions between the 3′-untranslated region and poly(A) tail via the HuR and poly(A)-binding protein complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1759:132-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nonet, M., C. Scafe, J. Sexton, and R. Young. 1987. Eucaryotic RNA polymerase conditional mutant that rapidly ceases mRNA synthesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:1602-1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palacios, I. M., D. Gatfield, D. St. Johnston, and E. Izaurralde. 2004. An eIF4AIII-containing complex required for mRNA localization and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Nature 427:753-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng, S. S., C. Y. Chen, N. Xu, and A. B. Shyu. 1998. RNA stabilization by the AU-rich element binding protein, HuR, an ELAV protein. EMBO J. 17:3461-3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rose, M., and D. Botstein. 1983. Construction and use of gene fusions to lacZ (beta-galactosidase) that are expressed in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 101:167-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruiz-Echevarria, M. J., K. Czaplinski, and S. W. Peltz. 1996. Making sense of nonsense in yeast. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21:433-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruiz-Echevarria, M. J., and S. W. Peltz. 2000. The RNA binding protein Pub1 modulates the stability of transcripts containing upstream open reading frames. Cell 101:741-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sachs, A. 2001. Physical and functional interactions between the mRNA cap structure and the poly(A) tail, p. 447-465. In N. Sonenberg et al. (ed.), Translational control of gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 50.Sachs, A. B., M. W. Bond, and R. D. Kornberg. 1986. A single gene from yeast for both nuclear and cytoplasmic polyadenylate-binding proteins: domain structure and expression. Cell 45:827-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shibuya, T., T. O. Tange, N. Sonenberg, and M. J. Moore. 2004. eIF4AIII binds spliced mRNA in the exon junction complex and is essential for nonsense-mediated decay. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:346-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thompson, J. S., M. L. Snow, S. Giles, L. E. McPherson, and M. Grunstein. 2003. Identification of a functional domain within the essential core of histone H3 that is required for telomeric and HM silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 163:447-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Torchet, C., G. Badis, F. Devaux, G. Costanzo, M. Werner, and A. Jacquier. 2005. The complete set of H/ACA snoRNAs that guide rRNA pseudouridylations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA 11:928-938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valentini, S. R., V. H. Weiss, and P. A. Silver. 1999. Arginine methylation and binding of Hrp1p to the efficiency element for mRNA 3′-end formation. RNA 5:272-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vasudevan, S., and S. W. Peltz. 2001. Regulated ARE-mediated mRNA decay in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 7:1191-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vinciguerra, P., and F. Stutz. 2004. mRNA export: an assembly line from genes to nuclear pores. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16:285-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vojtek, A. B., and S. M. Hollenberg. 1995. Ras-Raf interaction: two-hybrid analysis. Methods Enzymol. 255:331-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang, Y., C. L. Liu, J. D. Storey, R. J. Tibshirani, D. Herschlag, and P. O. Brown. 2002. Precision and functional specificity in mRNA decay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:5860-5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilusz, C. J., and J. Wilusz. 2004. Bringing the role of mRNA decay in the control of gene expression into focus. Trends Genet. 20:491-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilusz, C. J., M. Wormington, and S. W. Peltz. 2001. The cap-to-tail guide to mRNA turnover. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:237-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Windgassen, M., D. Sturm, I. J. Cajigas, C. I. Gonzalez, M. Seedorf, H. Bastians, and H. Krebber. 2004. Yeast shuttling SR proteins Npl3p, Gbp2p, and Hrb1p are part of the translating mRNPs, and Npl3p can function as a translational repressor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:10479-10491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wong, D. H., A. H. Corbett, H. M. Kent, M. Stewart, and P. A. Silver. 1997. Interaction between the small GTPase Ran/Gsp1p and Ntf2p is required for nuclear transport. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3755-3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zanchin, N. I., and D. S. Goldfarb. 1999. Nip7p interacts with Nop8p, an essential nucleolar protein required for 60S ribosome biogenesis, and the exosome subunit Rrp43p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1518-1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.