Abstract

Purpose

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is a common inhabitant of the bowel and vaginal flora, with known transmission routes including sexual contact and vertical transmission from mother to infant. Foodborne transmission is also possible, as GBS is a known fish and bovine pathogen. We conducted a prospective cohort study in order to identify risk factors for acquisition.

Methods

We identified risk factors for GBS acquisition among college women (n=129) and men (n=128) followed at 3-week intervals for 3 months.

Results

A doubling in sex acts significantly increased incidence of capsular type V by 80% (95% CI: 1.19, 2.58), and other non-Ia or Ib types combined by 40% (95% CI: 1.00, 2.06; incidence of capsular type Ia (OR=1.2; 95% CI: 0.71, 1.88 p=0.57) and Ib (OR=1.5, 95% CI: 0.75, 2.86, p=0.27) were elevated although not significantly. After adjustment for sexual activity and sexual history, gender, and eating venue, fish consumption increased risk of acquiring capsular types Ia and Ib combined 7.3 fold (95% CI: 2.34, 19.50), but not other capsular types. Beef and milk were not associated with GBS incidence.

Conclusions

Different GBS capsular types may have different transmission routes.

Keywords: Group B Streptococcus, Fish, Sexual Behavior, Epidemiology, Capsular Type, Transmission

GBS is a common inhabitant of the bowel and vaginal flora, with known transmission routes including sexual contact and vertical transmission from mother to infant. Colonization usually does not lead to disease except in vulnerable populations [1], such as the elderly and newborns. Evidence that GBS is a sexually transmitted infection (STI), includes its association with recent sexual activity, younger (adult) age, and more than one sex partner in the past 30 days [2], and the fact that it is found more frequently among patients attending STI than other clinics [3, 4, 6]. In addition, colonization rates are much lower among children aged 3 to 10 (4%) [12], and among adults who have never engaged in sexual activity (17% in women, 13% in men) [10] than among sexually active adults (38% in women, 24% in men) [10], However, GBS colonization has not been associated with increased lifetime numbers of sex partners or previous history of other STIs, traditional STI risk factors [5,6]. Within-couple transmission has been clearly demonstrated in both pregnant [7, 8] and non-pregnant [9] cohorts. By contrast, transmission of GBS following casual contact is low, as shown in studies of college roommates [10,11].

As GBS is a common bowel inhabitant, and a known bovine and fish pathogen, it is possible that GBS is transmitted through food or by the fecal-oral route. GBS was originally isolated as the causative agent of mastitis in cows, and is a pathogen of both wild and captive fish [13, 14]. Further, a comparison of the whole cell protein and physiological patterns of GBS serotype Ib isolated from fish and humans were highly similar, suggesting a common ancestor [13]. We previously identified associations of GBS colonization with eating certain foods, but the results were inconsistent [5, 10]. However, these studies were cross-sectional, so it is impossible to discern if the foods led to acquiring GBS or maintaining existing GBS carriage.

To investigate risk factors for GBS colonization, we conducted a prospective longitudinal cohort study among male and female college students living in a single dormitory.

Methods

Study Protocol

As described previously [10,11], 738 students who lived in a first year dormitory at the University of Michigan between January and February 2001 were invited to participate via an advertisement in their dormitory mailbox. We randomly sampled dormitory floors, and invited all inhabitants on the selected floors to participate (n=738). Overall, 63% ( 216 males and 246 females) consented and completed the enrollment protocol Following informed consent, participants completed a self-administered questionnaire and provided a throat and mouth (cheek) culture, self-collected initial-void urine, anal orifice and vaginal specimens. For anal orifice specimens, the swab did not pass the anal sphincter. Non-responders were sent up to three e-mail reminders and contacted by telephone. All participants positive for GBS and a random sample of those negative at enrollment were invited to return for four additional visits at 3, 6, 9 and 12 weeks post-enrollment. At each follow-up visit additional specimens were collected and participants completed a self-administered questionnaire. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan.

Of the 149 men and 150 women invited to participate in the follow-up study, 257 of the 299 (86%) completed the first follow-up; 82%, 80% and 79% completed the second, third and fourth follow-ups, respectively. Follow-up rates were virtually the same by gender. Participants were compensated for participation, with a bonus for completing all four follow-ups.

GBS Isolation

Specimens were self-collected as described previously [10] using the Culture Swab Plus Collection System [Baltimore Biological Labs (BBL); Sparks, MD] with Amies transport media. Following collection, rectal and vaginal specimens were inoculated in selective broth media containing gentamicin and nalidixic acid, incubated overnight at 37°C with CO2, subcultured onto trypticase soy agar (TSA) with 5% sheep blood, and incubated overnight. Urine specimens were subcultured directly to TSA. Suspect isolates were confirmed serologically as described in previous studies [5, 9].

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)

We used PFGE to determine whether participants colonized in multiple sites carried identical GBS strains, and to distinguish between continuous carriage and new infection with a different strain. PFGE methods were described previously [5, 9].

Capsular typing

We classified isolates into capsular types Ia, Ib, and II to VIII using DNA dot blot hybridization, as previously described [15]. For a subset of isolates, however, DNA hybridization was performed using an alternative anti-fluorescein-AP antibody, according to the manufacturer's protocol (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany), as the reagents used previously had been discontinued. Nontypeable isolates were probed for the presence of the GBS 16S RNA gene to verify that chromosomal DNA was present on the membrane when it was initially probed with the capsular-specific gene probes. DNA extraction for two isolates was found to be inadequate for capsular typing after repeated attempts and they were excluded from the analysis. When more than one isolate from a single individual had the same PFGE pattern, we assumed the isolates had the same serotype [16]. Thus, for each person, we capsular-typed only one randomly selected isolate from each PFGE band pattern observed. Serotype distributions of this collection have been presented previously [17].

Data Analysis

We estimated the 3-week incidence of GBS, by capsular type, for each putative risk factor and tested for statistical significance using the chi square test for dichotomous predictors and the Mantel-Haenszel chi square test for trend for ordinal predictors. We estimated the incidence using GBS at any colonization site. If an infected individual became colonized with a second capsular type, they were counted as an incident case for the second capsular type. The number of incident cases for capsular type Ib was small (n=5); as the associations of risk factors with capsular type Ib were very similar to those observed for capsular type Ia (n=14), we present the capsular-specific risk factors with capsular types Ia and Ib combined. There were 21 incident cases of capsular type V, and 19 incident cases of all other capsular types (not 1a, 1b, or V) combined.

We stratified by all variables where we observed a strong association with GBS incidence (risk ratio ≥ 2.0), and checked for confounding and effect modification. To simultaneously assess the effects of multiple variables, we fit a series of logistic regression models predicting the 3-week incidence of each GBS capsular type, and all capsular types combined. Initially we included all variables significant in the univariate analyses, and then added other variables one at a time. Non-significant variables were deleted, except for those retained for interpretation purposes. Since an individual can be colonized with more than one capsular type, all individuals without a particular capsular type were considered at risk. Further, if an individual cleared a capsular type, they were considered at risk to acquire it again. We had 4 individuals who cleared infection and became re-infected. To adjust for the effects of repeated measures, we repeated the final regression models included in the manuscript using generalized estimating equations (GEE). As these gave essentially the same results as those not adjusted using GEE, only the unadjusted models are presented.

As a follow-up to the previous models, we further investigated food choices, which are not necessarily independent. To determine the food(s) most associated with GBS incidence overall and by capsular type, we fit a series of logistic regression models including all foods measured, as well as variables significant in the previous analysis. We selected the variables most predictive of GBS incidence using the method of “all possible regressions” [18], which considers all possible subset models, and displays the best models at each step, first considering a single covariate, then considering two covariates, etc. From these listings of comparator models, the most predictive variables can be identified for further testing in more targeted models.

Because the frequencies of the various sexual activities (vaginal intercourse, anal intercourse, and passive and active oral sex) were highly correlated, and we observed an increase in GBS incidence with increasing frequency of each individual type of sexual activity, we created a summary variable of sexual activity: the maximum frequency among all types of sex acts reported in the interval. As the distribution of the maximum frequency of sex acts was highly skewed, we transformed this variable using log base 2, so the odds ratio is interpreted as the ratio of the odds of GBS incidence for a doubling in the number of sex acts. For example, an odds ratio of 1.5 corresponds to a 50% increase in the odds of GBS incidence with 4 versus 2 sex acts. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1. [19]

Results

Most of the 257 participants were white (86% of women 85% of men), and aged 19 years; all were residents of a single freshman dormitory. Most had engaged in sexual activity (84% of women and 70% of men), defined as vaginal, oral or anal intercourse, with a median age of first sex of 16 years for women and 17 years for men. In the baseline survey [10], 34% of the women and 20% of the men were colonized with GBS at one or more sites. As previously reported, the overall 3-week incidence of GBS was 11.3% (95% CI: 7.4 to 15.2%) among women and 8.8% (95% CI: 5.8 to 11.8%) among men; the most common capsular types were Ia and V [11]. The 3-week incidence of type Ia was 2.3% women and 2.4% for men, Ib was 1.6% for women and 0.9% for men and type V was 4.7% for women and 3.5% for men [11]. Since an individual can be colonized with more than one capsular type, all individuals without a particular capsular type were considered at risk. Further, if an individual cleared a capsular type, they were considered at risk to acquire it again.

Risk of Acquiring GBS by Sexual Activity

Engaging in any sexual activity, defined as vaginal, oral or anal intercourse during the previous three weeks was significantly associated with an increased incidence of GBS overall, and of all capsular types with the exception of types Ia and Ib, although the trend was in the same direction (Table 1). A significantly increased incidence of GBS with increasing frequency of vaginal intercourse, frequency of active and passive oral intercourse, the maximum frequency of the all types of sex acts measured, number of sex partners in the last 3 weeks, and number of sex partners in the past 12 months was observed overall and for capsular types excluding 1a, 1b or V. (The numbers engaging in anal intercourse were too small to provide stable estimates.) Using a condom was not associated with incidence, nor was sex with a new partner.

Table 1.

Incidence of Group B Streptococcus by capsular type /3 weeks/100 persons, by selected sexual behaviors in the previous 3 weeks (participants followed in 3 week intervals). 129 female and 128 male freshmen college students living in a single dormitory

| Characteristic | Person intervals | % Capsular type la or lb | % Capsular type V | % Non la, lb or V capsular types | % All capsular types combined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 340 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 8.8 |

| Female | 256 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 11.3 |

| Sex in last 3 weeks | |||||

| No | 377 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 6.9 |

| Yes | 216 | 3.7 | 6.0 | 5.6 | 15.3 |

| X2 p-value | 0.60 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.001 | |

| Frequency of vaginal intercourse previous 3 weeks | |||||

| None | 447 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 7.4 |

| 1 to 2 | 51 | 7.8 | 2.0 | 5.9 | 15.7 |

| 3 to 9 | 76 | 1.3 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 17.1 |

| 10 or more | 17 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 11.8 | 23.5 |

| Test for trend* | 0.75 | 0.10 | 0.001 | 0.002 | |

| Frequency of active oral sex in past 3 weeks | |||||

| None | 439 | 3.6 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 8.4 |

| 1 to 2 | 93 | 1.1 | 8.6 | 4.3 | 14.0 |

| 3 to 9 | 55 | 1.8 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 12.7 |

| 10 or more | 4 | 25.0 | 0 | 25.0 | 50.0 |

| Test for trend* | 0.39 | 0.23 | 0.009 | 0.005 | |

| Frequency of passive oral sex in past 3 weeks | |||||

| None | 435 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 7.8 |

| 1 to 2 | 88 | 1.1 | 11.4 | 4.6 | 17.1 |

| 3 to 9 | 61 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 6.6 | 13.1 |

| 10 or more | 6 | 16.7 | 0 | 16.7 | 33.3 |

| Test for trend* | 0.27 | 0.48 | 0.007 | 0.008 | |

| Maximum frequency of all sex acts in past 3 weeks | |||||

| None | 395 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 7.1 |

| 1 to 2 | 84 | 4.8 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 7.1 |

| 3 to 9 | 93 | 2.2 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 17.2 |

| 10 or more | 20 | 10.0 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 25.0 |

| Test for trend* | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.003 | 0.0004 | |

| Number of sex partners in last 3 weeks | |||||

| None | 378 | 2.9 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 7.1 |

| 1 | 191 | 3.7 | 6.3 | 5.2 | 15.2 |

| 2 | 11 | 9.1 | 0 | 9.1 | 18.2 |

| 3 or more | 12 | 0 | 0 | 8.3 | 8.3 |

| Trend test * | 0.71 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| Number of sex partners in past 12 months | |||||

| None | 191 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 5.2 |

| 1 | 219 | 3.2 | 4.6 | 3.2 | 11.0 |

| 2 | 85 | 2.4 | 5.9 | 2.4 | 10.6 |

| 3 or more | 100 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 16.0 |

| Test for trend* | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.005 | |

| Used a condom past 3 weeks | |||||

| No | 499 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 9.0 |

| Yes | 94 | 2.1 | 7.5 | 5.3 | 14.9 |

| X2 p-value | 0.52 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.08 | |

| Sex with new partner in previous 3 weeks? | |||||

| No sex | 380 | 3.9 | 6.1 | 1.8 | 6.8 |

| Sex old partner | 164 | 5.8 | 6.1 | 2.1 | 15.9 |

| Sex new partner | 52 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 13.5 |

| X2 p-value | 0.60 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.005 |

P value for the Mantel-Haenszel Chi-square test for trend

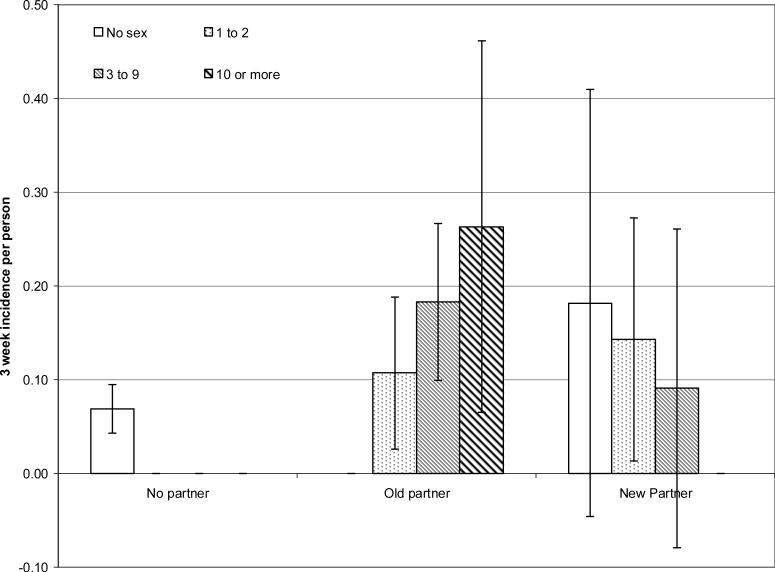

For an infection that is transmitted via sexual contact, we can indirectly measure risk of contact with an infected individual by inquiring about initiating a new sexual relationship. Because there is a transmission probability associated with each sex act, more sex acts with an infected partner increases risk. As the duration of GBS carriage is short, colonization among partnerships of longer duration may have already cleared from both partners, thus we anticipated observing a higher risk of GBS acquisition with a new than an existing partner, Further exploration of the apparent lack of association between acquiring a new partner and GBS risk revealed that frequency of sexual activity with a new sex partner in the previous interval was low. Indeed, no individuals reporting new sex partners in the previous interval reported a frequency of vaginal intercourse greater than 1 to 2 times per week (data not shown). However, for existing partners, the 3-week GBS incidence increased with increasing frequency of the maximum of sex acts measured (Figure 1). For new partnerships, the opposite trend was observed, although the confidence intervals are very wide. The highest incidence among those with a new partner occurred among those who reported no sex. Unfortunately, we did not measure other forms of intimate contact, such as kissing, that may lead to transmission, and there was no association with frequency of hands on partners genitals (p=0.40; data not shown).

1.

Three-week incidence rate of Group B Streptococcus of any capsular type, by maximum frequency of vaginal or oral intercourse in the previous 3 weeks, for those with no current partner, an existing partner or a new sex partner in the previous 3 weeks. Ticked lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. 129 female and 128 male freshmen college students living in a single dormitory.

Risk of Acquiring GBS by Eating Selected Foods, Places Ate and Hand Washing

There was no increase in the 3-week GBS incidence by capsular type or overall with eating pork, beef, chicken or eggs or drinking milk (Table 2). However, we observed a trend of greater incidence of capsular types Ia and Ib with eating fish more frequently, and for all capsular types combined. There was also a trend of eating yogurt and incidence of capsular types Ia and Ib but no other capsular type; cheese and ice cream showed no trends with any capsular type. There was little association with eating fresh or canned fruit, but eating raw vegetables was associated with an increased incidence of all capsular types but capsular type V; we also observed a trend of increasing incidence of capsular type Ia and Ib with eating cooked vegetables. In the vast majority (99%) of the risk periods, students reported eating at least once a week in their dormitory in the previous interval; however, those that did not had almost four times the incidence of GBS. Those who ate at a ‘sit down’ restaurant one or more times a week were also more likely to acquire GBS.

Table 2.

Incidence/3 weeks/100 persons of Group B Streptococcus by capsular type, by eating selected foods 1 or more times per week, places ate and hand washing practices in the previous 3 weeks participants followed in 3 week intervals. 129 female and 128 male freshmen college students living in a single dormitory

| Food | Person intervals | % Capsular type la or lb | % Capsular type V | % Non la, lb or V capsular types | % All capsular types combined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pork | |||||

| None | 322 | 3.7 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 9.6 |

| 1 time/week | 148 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 10.1 |

| 2−3 times/week | 101 | 3.0 | 5.9 | 4.0 | 12.9 |

| 4 or more | 16 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Test for trend* | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.75 | 0.87 | |

| Beef | |||||

| None | 119 | 5.0 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 12.6 |

| 1 time/week | 141 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 10.6 |

| 2−3 times/week | 213 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 8.9 |

| 4 or more | 118 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 8.5 |

| Test for trend* | 0.37 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.33 | |

| Chicken | |||||

| None | 46 | 6.5 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 10.9 |

| 1 time/week | 47 | 0.0 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 4.3 |

| 2−3 times/week | 255 | 2.4 | 5.1 | 5.5 | 12.9 |

| 4 or more | 247 | 4.1 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 7.7 |

| Test for trend* | 0.73 | 0.35 | 0.53 | 0.46 | |

| Fish | |||||

| None | 299 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 7.4 |

| 1 time/week | 212 | 1.9 | 5.7 | 3.3 | 10.9 |

| 2 −3 times/week | 72 | 9.7 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 15.3 |

| 4 or more times | 4 | 50.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 75.0 |

| Test for trend* | 0.0001 | 0.07 | 0.77 | 0.001 | |

| Eggs | |||||

| None | 156 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 7.7 |

| 1 time/week | 188 | 1.6 | 6.9 | 3.7 | 12.2 |

| 2−3 times/week | 170 | 5.3 | 0.6 | 4.1 | 10.0 |

| 4 or more | 76 | 1.3 | 3.9 | 2.6 | 7.9 |

| Test for trend* | 0.83 | 0.54 | 0.73 | 0.95 | |

| Milk | |||||

| None | 41 | 12.2 | 2.4 | 7.3 | 22.0 |

| 1 time/week | 51 | 2.0 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 9.8 |

| 2−3 times/week | 132 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 5.3 |

| 4−6 times/week | 110 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 7.3 |

| Daily | 261 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 11.5 |

| Test for trend* | 0.14 | 0.55 | 0.99 | 0.63 | |

| Yogurt | |||||

| None | 321 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 4.1 | 10.0 |

| 1 time/week | 136 | 1.5 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 8.8 |

| 2−3 times/week | 73 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 0.0 | 11.0 |

| 4 or more | 65 | 6.2 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 10.8 |

| Test for trend* | 0.05 | 0.91 | 0.22 | 0.73 | |

| Ice Cream | |||||

| None | 113 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 8.0 |

| 1 time/week | 162 | 0.6 | 4.3 | 6.2 | 11.1 |

| 2−3 times/week | 202 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 2.0 | 9.5 |

| 4 or more | 119 | 5.0 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 10.9 |

| Test for trend* | 0.22 | 0.77 | 0.96 | 0.61 | |

| Cheese | |||||

| None | 15 | 13.3 | 0 | 13.3 | 26.7 |

| 1 time/week | 27 | 0.0 | 18.4 | 3.7 | 22.2 |

| 2−3 times/week | 200 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 6.5 |

| 4 or more | 353 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 10.2 |

| Test for trend* | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.76 | 0.74 | |

| Fresh fruit | |||||

| None | 35 | 5.7 | 0 | 2.9 | 8.6 |

| 1 time/week | 125 | 0.8 | 4.0 | 3.2 | 8.0 |

| 2−3 times/week | 239 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 9.2 |

| 4 or more | 196 | 3.6 | 5.1 | 3.6 | 12.2 |

| Test for trend* | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.81 | 0.13 | |

| Canned fruit | |||||

| None | 237 | 1.3 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 7.6 |

| 1 time/week | 129 | 4.7 | 3.9 | 4.7 | 13.2 |

| 2−3 times/week | 109 | 6.4 | 3.7 | 1.8 | 11.9 |

| 4 or more | 120 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 9.2 |

| Test for trend* | 0.36 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.54 | |

| Raw vegetables | |||||

| None | 125 | 2.4 | 5.6 | 0 | 8.0 |

| 1 time/week | 122 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 6.7 |

| 2−3 times/week | 170 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 5.3 | 7.1 |

| 4 or more | 178 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 3.9 | 16.3 |

| Test for trend* | 0.03 | 0.62 | 0.06 | 0.007 | |

| Cooked vegetables | |||||

| None | 56 | 3.6 | 5.4 | 1.8 | 10.7 |

| 1 time/week | 111 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 3.6 | 9.0 |

| 2−3 times/week | 232 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 8.2 |

| 4 or more | 196 | 5.6 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 12.2 |

| Test for trend* | 0.03 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.26 | |

| Ate at dormitory | |||||

| No | 6 | 16.7 | 0 | 16.7 | 33.3 |

| Yes | 587 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 9.4 |

| X2 p-value | 0.06 | 0.65 | 0.06 | 0.05 | |

| Ate at another dormitory | |||||

| No | 245 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 8.2 |

| Yes | 330 | 3.9 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 9.1 |

| X2 p-value | 0.32 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.70 | |

| Ate at fast food restaurant | |||||

| No | 146 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 5.5 |

| Yes | 445 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 10.6 |

| X2 p-value | 0.71 | 0.49 | 0.05 | 0.07 | |

| Ate at sit down restaurant | |||||

| No | 114 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 4.4 |

| Yes | 467 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 11.1 |

| X2 p-value | 0.67 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.03 | |

| Frequency of hand washing | |||||

| <3 times/day | 75 | 2.7 | 6.7 | 2.7 | 12.0 |

| 3 to 5 times/day | 361 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 10.5 |

| 6 or more times/day | 150 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 7.3 |

| Test for trend* | 0.36 | 0.18 | 0.96 | 0.22 |

P value for the Mantel-Haenszel Chi square test for trend

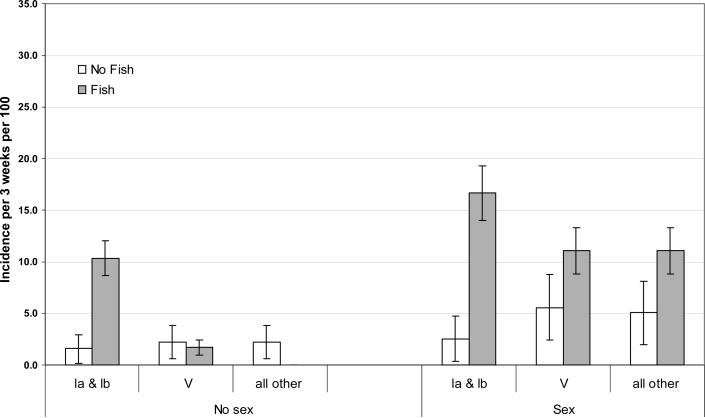

The strong association with sexual activity and previous studies [4-7, 9, 10] suggests that sexual transmission occurs. Therefore, we stratified the associations for each food item by sexual activity in the past 3 weeks to identify possibly modification or confounding by sexual activity. After stratification, the association with eating fish, but no other food item, remained (Figure 2). Among those engaging in sexual activity in the previous 3 weeks, we observed an increased risk of GBS for each capsular type grouping with fish consumption. However, among those who reported no sexual activity in the previous interval, fish consumption increased the incidence only for capsular types Ia and Ib combined (incidence among fish eaters 10.3% out of 58 risk periods versus 1.6% out of 319 risk periods among non-eaters; among those engaging in sexual activity the corresponding incidences were 16.7% out of 18 risk periods versus 2.5% out of 198 risk periods).

2.

Three-week incidence rate of Group B Streptococcus by capsular type, fish consumption and sexual activity in the previous 3 weeks. Ticked lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. 129 female and 128 male freshmen college students living in a single dormitory.

Multivariable Analysis

We further explored these associations by fitting a series of multivariable logistic regressions, modeling the incidence of each capsular type grouping as the outcome, as well as the incidence of all capsular types combined (Table 3). Fish consumption twice or more times a week was associated with a 7.3 fold increase (95% CI: 2.78, 18.90) in the odds of acquiring capsular types Ia and Ib combined, after adjusting for frequency of sex acts (the log base 2 of the maximum of frequency of vaginal sex and oral sex), number of sex partners in the previous year, frequency of eating in the dormitory, and gender. When we ran models for capsular types la and lb separately, including only frequency of sex acts, gender, and fish consumption in the model, the odds ratios for fish eating remained significant for capsular type Ia (OR=7.8; 95% CI: 2.6, 23.1) and marginally so for capsular type Ib (OR=5.5; 95% CI: 0.9, 34.2), reflecting the small number of incidence capsular type Ib acquisitions. The frequency of sexual acts was not statistically significantly associated with acquiring either capsular type Ia (OR=1.2; 95% CI: 0.71, 1.88 p=0.57) or Ib (OR=1.5, 95% CI: 0.75,2.86, p=0.27).

Table 3.

Risk factors for acquiring Group B Streptococcus by capsular type. Logistic regression model predicting incidence of a capsular type or capsular type grouping, using all other data as reference. 129 female and 128 male freshmen college students living in a single dormitory.

| Risk factor | Beta | Std Error | OR | (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capsular type la or lb | |||||

| Log frequency of sex acts* | 0.172 | 0.220 | 1.2 | (0.77,1.83) | 0.43 |

| Number of sex partners previous year | 0.079 | 0.149 | 1.1 | (0.81,1.45) | 0.59 |

| Eats fish 2 or more times per week | 1.982 | 0.489 | 7.3 | (2.78,18.90) | <0.001 |

| Frequency eats in the dormitory | −0.220 | 0.277 | 0.80 | (0.47,1.38) | 0.43 |

| Male gender | −0.100 | 0.509 | 0.90 | (0.33,2.45) | 0.84 |

| Capsular type V | |||||

| Log frequency of sex acts* | 0.560 | 0.198 | 1.8 | (1.19,2.58) | 0.001 |

| Number of sex partners previous year | −0.244 | 0.202 | 0.8 | (0.53,1.16) | 0.23 |

| Eats fish 2 or more times per week | 0.538 | 0.659 | 1.7 | (0.47,6.23) | 0.41 |

| Frequency eats in the dormitory | 0.786 | 0.520 | 2.2 | (0.79,6.07) | 0.13 |

| Male gender | −0.313 | 0.495 | 0.73 | (0.38,1.93) | 0.53 |

| All other capsular types | |||||

| Log frequency of sex acts* | 0.362 | 0.184 | 1.4 | (1.00,2.06) | 0.05 |

| Number of sex partners previous year | 0.328 | 0.117 | 1.4 | (1.1,1.75) | 0.005 |

| Eats fish 2 or more times per week | −0.134 | 0.786 | 0.88 | (0.19,4.08) | 0.87 |

| Frequency eats in the dormitory | −0.504 | 0.253 | 0.6 | (0.37,0.99) | 0.05 |

| Male gender | −0.024 | 0.508 | 0.9 | (0.36,2.64) | 0.96 |

| All capsular types, combined | |||||

| Log frequency of sex acts* | 0.383 | 0.119 | 1.5 | (1.16,1.85) | 0.001 |

| Number of sex partners previous year | 0.142 | 0.082 | 1.2 | (0.98,1.36) | 0.08 |

| Eats fish 2 or more times per week | 1.113 | 0.354 | 3.0 | (1.51,6.10) | 0.002 |

| Frequency eats in the dormitory | −0.136 | 0.183 | 0.9 | (0.61,1.25) | 0.46 |

| Male gender | −0.085 | 0.301 | 0.9 | (0.51,1.66) | 0.78 |

Risk periods calculated assuming no infection with multiple capsular types, so is a slight under-estimate

Log base 2 of maximum (frequency oral sex, vaginal sex), interpreted as the ratio of the odds of GBS incidence for a doubling in the number of sex acts. For example, an OR of 1.7 is interpreted as a 70% increase in odds of GBS with a doubling in the number of sex acts.

By contrast, there was no statistically significant association between fish consumption and acquiring capsular type V or other capsular types. The frequency of sex acts in the previous 3 weeks was, however, strongly associated with increased risk of acquiring capsular type V and all non-Ia, Ib or V capsular types, but not types Ia or Ib. Number of sex partners in the previous year was also a significant predictor of acquiring capsular types other than V, Ia or Ib.

After adjustment for sexual activity and fish consumption, there was no longer a significant association of yogurt (OR=1.1; 95% CI: 0.8, 1.5) and raw vegetables (OR=1.1; 95% CI: 0.4, 2.8) with overall or capsular-specific GBS incidence (data not shown). Adjustment for sexual activity did not change the associations between other food variables and GBS incidence either overall or by capsular type. Repeating the models adjusting for repeated measures using generalized estimating equations also did not change the observed associations.

Discussion

In a prospective cohort study of 257 healthy male and female college students living in a single college dormitory followed at 3 week intervals for 12 weeks, we observed sexual activity, particularly frequency of vaginal or oral intercourse, to be the strongest predictor of GBS incidence for capsular types V and all types other than Ia, Ib, and V. However, even among those not sexually active the rate of GBS was surprisingly high, leading us to consider other sources of exposure. The finding of a 7.3 fold increase (95% CI 2.78, 18.90) in GBS capsular types Ia and Ib incidence with fish consumption two or more times a week in the previous 3 weeks, after adjustment for frequency of sex acts during the previous 3 weeks, gender, number of sex partners in the previous year and frequency of eating in the dormitory, led us to consider the potential of fish as a foodborne source of GBS. We found no associations with other food items, including beef, milk and milk products, which in theory also might be a source of GBS, perhaps because milk from cows with clinical mastitis is not sold. We also found no significant association with handwashing practices, although there was a trend toward decreasing incidence with increased frequency of handwashing for capsular type V and all capsular types combined.

We are aware of no other reports of GBS risk factors by capsular type or of an association between GBS acquisition and fish consumption. Although the results require confirmation, transmission of GBS via fish is biologically plausible, as GBS serotype Ib is a known fish pathogen [13], and when strains colonizing fish were compared to human strains they had identical whole protein and physiologic patterns [20]. GBS of unknown serotypes also colonize fish [13], which may explain why we observed an association between fish consumption and capsular type Ia. Should this result be confirmed, the findings have public health implications for the diet of individuals at high risk of GBS disease, e.g., pregnant women and adults with underlying chronic conditions.

GBS serotype Ib has been isolated from a wide variety of fish, both farm raised and wild, including tilapia, mullet and bluefish [13]. However, we found no reports describing colonization rates among apparently healthy fish; although farm raised fish are vaccinated against GBS disease this may not affect colonization. We estimate that if the association were causal in our sample, 86% of all persons colonized with capsular type Ia or Ib who ate fish could attribute their colonization to eating fish. Given that serotypes Ia and Ib cause ∼20% of all neonatal disease and adult disease [21-23], if serotype Ia is also found in fish, fish consumption may account for as much as 17% (86% of 20%) of the cases of GBS disease among neonates and adults. It remains to be determined the extent that food preparation influences risk of acquisition, as we had no information regarding how the fish was prepared. It seems likely that eating fish raw would pose a greater risk than cooked. We did note an increase in GBS acquisition among students who reported eating in “sit down” restaurants, although we did not inquire about the food or the restaurant type. Whether GBS is found among commercially sold fish and survives normal cooking temperatures is unknown.

Despite the supporting evidence and biological plausibility, this is first report of an association between eating fish and acquiring GBS, and thus should be viewed with caution until replicated in other studies. Given that we tested the association with 13 food items, in addition to many other variables, there is always the possibility that this finding is an alpha error.

Acquisition of capsular types other than Ia and Ib was strongly associated with frequency of sexual intercourse during the previous 3 weeks. This finding is consistent with a Pittsburgh study, which followed 1089 women and found sexual activity in the 5 days prior to culture and frequent sexual intercourse in the previous 4 months predicted vaginal acquisition of GBS, although the authors did not report associations by capsular type [6]. Acquisition of types Ia and Ib appear to be essentially independent of sexual activity, or any effect was too small to detect given our sample size. Although GBS has been strongly associated with sexual activity, it is unclear what type(s) of sexual activity confer the highest risk. Unfortunately, the frequencies of sexual behaviors measured in our study were highly correlated, so we can provide no further insight. The lack of a protective effect with condom use was surprising. However, as GBS is a common bowel inhabitant and can be transmitted by the fecal oral route, it may be that oral sex is more important for transmission than vaginal intercourse. Because we studied sites in addition to the vagina, any locally protective effect of condoms may have been dwarfed by transmission through other routes. Alternatively, normal condom use may be insufficient to protect against GBS transmission.

Although we observed strong effects, our association was with GBS colonization, not disease, and was conducted among healthy young college students. Pregnant women or adults with underlying chronic conditions may be more or less susceptible to colonization following exposure either from eating fish or via sexual intercourse, which would modify the observed risk of colonization. Further studies confirming that GBS found in fish can colonize humans and cause human disease are required.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Patricia Tallman for laboratory support, Katie Neighbors for coordinating the study and Laura Howard for data management. This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI44868 (BF) and AI051675 (BF) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schuchat A. Group B streptococcal disease: from trials and tribulations to triumph and trepidation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;33:751–756. doi: 10.1086/322697. Epub 2001 Aug 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill HR. Group B streptococcal infections. In: Holmes KK, et al., editors. Sexually transmitted diseases. Second Edition McGraw-Hill; New York: 1990. pp. 851–861. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker CJ, Goroff DK, Alpert S, Crockett VA, Zinner SH, Evrard JR, et al. Vaginal colonization with Group B Streptococcus: a study in college women. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1977;134:392–397. doi: 10.1093/infdis/135.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newton ER, Butler MC, Shain RN. Sexual behavior and vaginal colonization by group B Streptococcus among minority women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;88:377–82. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00264-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bliss SJ, Manning SD, Tallman P, Baker CJ, Pearlman MD, Marrs CF, et al. Group B Streptococcus colonization in male and non-pregnant female university students: A cross sectional prevalence study. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;34:184–190. doi: 10.1086/338258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyn LA, Moore DM, Hillier SL, Krohn MA. Association of sexual activity with colonization and vaginal acquisition of Group B Streptococcus in nonpregnant women. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;155:949–57. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.10.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto T, Nagasawa I, Nojima M, Yoshida K, Kuwabara Y. Sexual transmission and reinfection of group B streptococci between spouses. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecological Research. 1999;25:215–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1999.tb01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weindling AM, Hawkins JM, Coombes MA, Stringer J. Colonisation of babies and their families by group B streptococci. British Medical Journal of Clinical Research Ed. 1981;283:1503–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.283.6305.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manning SD, Tallman P, Baker CJ, Gillespie B, Marrs CF, Foxman B. Determinants of co-colonization with Group B. Streptococcus among heterosexual college couples. Epidemiology. 2002;13:533–539. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manning SD, Neighbors K, Tallman P, Gillespie B, Marrs CF, Borchardt SM, et al. Prevalence of group B Streptococcus colonization and potential for transmission by casual contact in healthy, young men and women. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004;39:380. doi: 10.1086/422321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foxman B, Gillespie B, Manning SD, Howard L, Tallman P, Zhang L, et al. Incidence and Duration of Group B Streptococcus by Capsular Type Among First Year Male and Female College Students Living in a Single Dormitory. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;163:544–551. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammerschlag MR, Baker CJ, Alpert S, Kasper DL, Rosner I, Thurston P, et al. Colonization with group B streptococci in girls under 16 years of age. Pediatrics. 1977;60:473–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans JJ, Klesius PH, Gilbert PM, Shoemaker CA, Al Sarawi MA, Landsberg J, et al. Characterization of β-haemolytic Group B Streptococcus agalactiae in culture seabream, Sparus auratus L., and wild mullet, Liza klunzingeri (Day), in Kuwait. Journal of Fish Diseases. 2002;25:505–513. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berridge BR, Bercovier H, Frelier PF. Streptococcus agalactiae and Streptococcus difficile 16S-23S intergenic rDNA: genetic homogeneity and species-specific PCR. Veterinary Microbiology. 2001;78:165–73. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borchardt SM, Foxman B, Chaffin DO, Rubens CE, Tallman PA, Manning SD, et al. A Comparison of GBS Capsular Typing Methods: DNA Dot Blot Hybridization vs. Lancefield's Capillary Precipitin Method. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2004;42:146–150. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.146-150.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: Criteria for bacterial typing. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borchardt SM, Zhang L, McCoy SI, Tallman PA, DeBusscher JH, Marrs CF, et al. Frequency of Antimicrobial Resistance among Invasive and Colonizing Group B Streptococcal Isolates. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2006;6:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myers RH. Classical and Modern Regression with Applications. 2nd edition Duxbury Press; Belmont, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.SAS V9.1. Copyright (c) 2002−2003. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC, USA: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elliott JA, Facklam RR, Richter CB. Whole-cell protein patterns of nonhemolytic group B, type Ib, streptococci isolated from humans, mice, cattle, frogs, and fish. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1990;28:628–630. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.628-630.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Persson E, Berg S, Trolfors B, Larsson P, Ek E, Backhaus E, et al. Serotypes and clinical manifestations of invasive group B streptococcal infections in western Sweden 1998−2001. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2004;10:791–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies HD, Raj S, Adair C, Robinson J, McGeer A. Alberta GBS Study Group. Population-based active surveillance for neonatal group B streptococcal infections in Alberta, Canada: implications for vaccine formulation. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2001;20:879–84. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berg S, Trolfors B, Lagergard T, Zackrisson G, Claesson BA. Serotypes and clinical manifestations of group B streptococcal infections in western Sweden. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2000;6:9–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]