Abstract

Background

This study examined patterns of use of three adult preventive services— influenza vaccination, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination, and colorectal cancer (CRC) screening; factors associated with different use patterns; and reasons for non-use.

Methods

Data from 3675 individuals aged 65 and older responding to the 2004 National Adult Immunization Survey, which included a CRC screening module, were analyzed in 2005–2006. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize patterns of use of preventive services, and to assess reasons for non-use. Polytomous logistic regression modeling was used to identify predictors of specific use patterns.

Results

Thirty-seven percent of respondents were current with all three preventive services; 10% were not current with any. Preventive services use varied by demographic and health care utilization characteristics. Having a recent visit to a doctor or other health provider was the most consistent predictor of use. Concern about side effects was the most frequently-cited reason for not having an influenza vaccination (25%), while not knowing that the preventive service was needed was the most common reason for non-use of pneumonia vaccination (47%) and CRC tests (44% FOBT, 51% sigmoidoscopy, 47% colonoscopy).

Conclusions

Rates of influenza and pneumonia vaccination and CRC screening are suboptimal. This is especially apparent when examining the combined use of these services. Patient and provider activation and the new “Welcome to Medicare” benefit are among the strategies that may improve use of these services among older Americans. Ongoing monitoring and further research are required to determine the most effective approaches.

INTRODUCTION

Immunization and screening are important components of preventive health care for older Americans. Annual influenza vaccination and one-time pneumococcal vaccination with pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV) for all adults aged 65 and older are recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.1 In addition, routine screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) beginning at age 50, with no upper age limit, is recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force2 and other national expert groups. Both types of immunization and CRC screening have been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality,1,3 and they are covered benefits under the Medicare program.4 They also have been ranked highly as important and cost-effective preventive services.5 Nevertheless, influenza and pneumonia vaccination and CRC screening have lower utilization among adults aged 65 and older compared with other Medicare-covered preventive services such as Pap smears, mammograms, and cholesterol checks.6

Previous studies have examined rates of use of adult immunization and/or CRC screening, documenting variations by gender, race/ethnicity, and geographic location.7–12 Studies that have examined more than one of these preventive services have generally assessed each service separately. Less is known about patterns of use by preventive service type, or whether older adults’ reasons for not using these services are similar. Understanding patterns of use and reasons for non-use may help in identifying and implementing strategies to improve use. The present study adds to the public health literature by examining, in a national sample of older adults, patterns of use of the influenza vaccination (commonly known as the flu shot), pneumococcal vaccination with PPV (commonly known as the pneumonia shot), and CRC screening; the demographic, health status, and health care utilization factors associated with different use patterns; and reasons for non-use of these preventive services.

METHODS

Data Source

Data from the 2004 National Adult Immunization Survey (NAIS) were used in this study. The 2004 NAIS, sponsored by the National Immunization Program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, was designed to provide national estimates of influenza vaccine coverage among individuals aged 50 years and older, and of pneumococcal vaccine coverage among individuals aged 65 and older. In addition, the 2004 NAIS included a module on CRC screening practices that was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute and administered to individuals aged 65 and older. This module was adapted from a survey of Medicare beneficiaries conducted in North and South Carolina in 2001 and 2002 (http://www.mrnc.org/mrnc_web/data/crcproject.aspx).

The NAIS sample was drawn from the first quarter of the 2004 National Immunization Survey sampling frame and represented a national, random-digit dial sample of households.13 The survey was administered by telephone between January and May of 2004. Households with residents in the civilian, noninstitutionalized population who were aged 50 or older were selected for the NAIS sample. After determining the eligibility of the persons in the household, one individual was selected to participate in the interview. The survey response rate, calculated according to Council of American Survey Research Organizations guidelines, was 51.4%. A total of 3,675 interviews were conducted with persons aged 65 years and older.

Respondents aged 65 and older were asked whether they had been vaccinated against influenza ever and during the past flu season (i.e., between September 2003 and the date of the interview); if vaccinated during the past flu season, they were asked the type of facility from which they received the vaccination, and if not vaccinated during the past flu season, they were asked their main reason for not receiving a vaccination. Respondents were also asked whether they had ever been vaccinated against pneumonia, and if they had not, their main reason for not having this immunization. Next, after hearing descriptions of fecal occult blood testing (FOBT), sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy, they were asked whether they had ever received each test, with follow-up questions to ascertain when they had their most recent test, and the reason for the test. Respondents who had never had the test were asked, “what is the main reason you have not had this test?”, and were read a list of possible reasons from which to choose. They also were asked questions about demographics, health status, and whether they had seen a doctor or other health care professional between September 2003 and the date of the interview. The interview took about 15 minutes to complete. More information about the 2004 NAIS, including the survey instrumentation, is available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nis/faq_nais.htm.

Measures

Demographic measures included the respondent’s age, race/ethnicity, gender, educational attainment, and residence in a metropolitan statistical area (yes or no). Respondents reporting a racial/ethnic background other than non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or Hispanic (n=92) were grouped with non-Hispanic whites due to small sample sizes and to permit stable estimates. Health status was measured by respondents’ self-reports of whether they were in excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor health. Health care utilization was measured by whether respondents had visited a doctor or other health care professional recently.

Respondents were regarded as current with influenza vaccination recommendations if they reported having a flu shot during the last flu season. They were considered current with PPV recommendations if they reported ever having a pneumonia shot. They were considered current with CRC screening recommendations if they reported having FOBT in the past year, sigmoidoscopy in the past 5 years, or colonoscopy in the past 10 years, regardless of the reason for the test.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize respondents’ immunization and CRC screening status, including patterns of use of the three preventive services. Descriptive statistics also were used to assess respondents’ reasons for not having a flu shot, pneumonia shot, or CRC screening tests if they were not current with these preventive services, and place of service for the most recent flu shot.

Contingency tables with chi-square tests were used to examine associations between demographic, health status, and health care utilization variables and preventive services use categories. A polytomous logistic regression model was estimated to assess demographic, health status, and health care utilization predictors of specific patterns of use. The model included a five-level dependent variable (not current with any preventive service, current with flu and/or pneumonia shot only, current with CRC screening only, current with CRC screening and flu or pneumonia shot, current with all three preventive services); lack of currency with any preventive service was the referent group. The interaction of race/ethnicity and education was tested in the model because of its previously-reported significance in an analysis of vaccinations.10 It was not statistically significant, and therefore was excluded from the final model.

To determine whether currency with one preventive service predicts currency with another, a subsidiary analysis was conducted in which three separate logistic regression models were estimated. Currency with the flu shot, the pneumonia shot, and CRC screening were the dependent variables in these models, which incorporated the same set of explanatory variables as in the previously-described polytomous logistic regression model. Additional explanatory variables in these models were currency with the pneumonia shot and CRC screening (flu shot model); currency with the flu shot and CRC screening (pneumonia shot model); and currency with the flu and pneumonia shots (CRC screening model).

The Survey Data Analysis (SUDAAN) computer package version 9.0.1 was used for all analyses. All analyses incorporate survey weights that adjust for the probability of selection into the sample, presence of multiple telephone lines in the household, and survey nonresponse. The analyses were conducted in 2005–6.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Population

Over half of the respondents were between 65 and 74 years of age and female; about 13% were of non-Hispanic black or Hispanic race/ethnicity (Table 1). One-third had more than a high school education, and over three-quarters resided in a metropolitan statistical area. Three-quarters rated their health status as excellent, very good, or good. Only 12% indicated that they had not had a recent visit to a doctor or other health care professional. Seventy-four percent reported being current with flu shot recommendations, while 64% were current with pneumonia shot and 58% with CRC screening recommendations. When assessed by specific modality, 7% were current with CRC screening by FOBT only, 37% by colorectal endoscopy only, and 11% by both FOBT and colorectal endoscopy (data not shown). The demographic distribution of the weighted sample was comparable to the U.S. Census Bureau report of the 2004 population of adults aged 65+ for sex, race, and educational attainment. More information about this population can be found at: http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ACSSAFFPeople?_submenuld=people_3&_sse=on.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 2004 National Adult Immunization Survey, respondents aged 65 and older (N = 3675)

| Demographic | na | %b | (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 65–69 | 1020 | 28.4 | (26.1–30.9) |

| 70–74 | 966 | 25.5 | (23.3–27.9) |

| 75–79 | 787 | 20.8 | (18.6–23.1) |

| 80+ | 902 | 25.3 | (23.0–27.7) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white/other | 2449 | 87.3 | (85.9–88.5) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 806 | 7.3 | (6.3–8.4) |

| Hispanic | 420 | 5.4 | (4.7–6.3) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 2381 | 57.4 | (54.7–60.1) |

| Male | 1294 | 42.6 | (39.9–45.3) |

| Education | |||

| < high school | 975 | 33.0 | (30.4–35.8) |

| High school graduate | 1290 | 32.5 | (30.1–35.0) |

| > high school | 1410 | 34.5 | (32.1–36.9) |

| Metropolitan area | |||

| Yes | 2999 | 80.2 | (78.1–82.2) |

| No | 676 | 19.8 | (17.8–21.9) |

| Health status | |||

| Self-rated health status | |||

| Excellent/very good/good | 2719 | 74.9 | (72.5–77.2) |

| Fair/poor | 927 | 24.0 | (21.8–26.4) |

| Don’t know/refused/missing | 29 | 1.1 | (0.6–2.0) |

| Healthcare utilization | |||

| Recent doctor/other health provider visit | |||

| Yes | 3258 | 87.7 | (85.8–89.4) |

| No | 403 | 11.8 | (10.2–13.7) |

| Don’t know/refused | 14 | 0.5 | (0.2–1.0) |

| Immunization | |||

| Current with flu shotc | |||

| Yes | 2540 | 74.1 | (71.8–76.3) |

| No | 1092 | 25.2 | (23.1–27.5) |

| Don’t know | 43 | 0.7 | (0.4–1.1) |

| Current with pneumonia shotd | |||

| Yes | 2211 | 63.7 | (61.1–66.2) |

| No | 1244 | 31.4 | (29.0–33.9) |

| Don’t know | 220 | 4.9 | (3.9–6.1) |

| Colorectal cancer screening | |||

| Current with colorectal cancer screeninge | |||

| Yes | 2033 | 58.0 | (55.3–60.6) |

| No | 1351 | 34.5 | (32.0–37.0) |

| Unknown | 291 | 7.6 | (6.3–9.1) |

Unweighted n

Weighted %

Had a flu shot during the past flu season (i.e., between September 2003 and the date of the interview)

Ever had a pneumonia shot

Had FOBT in the past year, sigmoidoscopy in the past 5 years, and/or colonoscopy in the past 10 years

CI, confidence interval; FOBT, fecal occult blood test

Patterns of Preventive Services Use

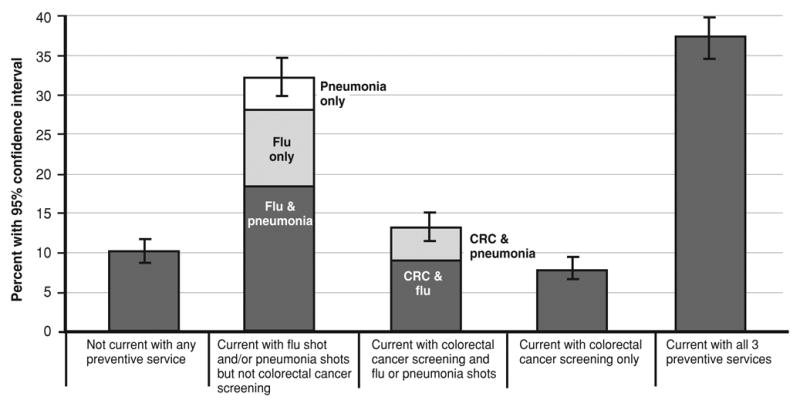

Thirty-seven percent of respondents were current with all three preventive services, while 10% were not current with any of them (Figure). Thirty-two percent were current with one or both vaccinations, but not CRC screening. Thirteen percent were current with CRC screening and one of the vaccinations, while eight percent were current with CRC screening only.

Figure 1. Patterns of use of 3 preventive services, 2004 National Adult Immunization Survey (N = 3675).

CI, confidence interval

Ninety percent of respondents who were current with the flu shot received this service in a medically-related place such as a doctor’s office (>50%), clinic/health center (20%), or pharmacy/drug store (6%), compared with only 10% who received the shot in a non-medically related place such as at home or work. Estimates for where the flu shot was received were similar regardless of whether respondents were current with the pneumonia shot or CRC screening (data not shown).

Table 2 shows preventive services by use category and according to respondents’ demographic, health status, and health care utilization characteristics. It identifies the most prevalent use categories for various groups. For example, being current with all three preventive services was the most prevalent use category for respondents aged 65–79, of non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity, with a high school or more education, and with a recent doctor/other health provider visit. In contrast, currency with one or both vaccinations but not CRC screening was the most prevalent use category among those aged 80+, of Hispanic or non-Hispanic black race/ethnicity, with less than a high school education, and who lacked a recent doctor/other health provider visit.

Table 2.

Preventive services use by demographic, health status, and health care utilization characteristics, 2004 National Adult Immunization Survey (N = 3675)

| Not current with any of the 3 | Current with flua and/or pneumoniab shot but not CRC screening | Current with CRC screeningc and flu or pneumonia shot | Current with CRC screening only | Current with all 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nd | %e | nd | %e | nd | %e | nd | %e | nd | %e | |

| Demographic | ||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||

| 65–69 | 159 | 12.0 | 259 | 25.9 | 181 | 16.6 | 115 | 10.9 | 306 | 34.8 |

| 70–74 | 128 | 8.5 | 277 | 29.2 | 128 | 15.0 | 99 | 7.9 | 334 | 39.4 |

| 75–79 | 76 | 7.4 | 265 | 29.7 | 99 | 14.3 | 59 | 5.8 | 288 | 42.8 |

| 80+ | 116 | 11.4 | 362 | 43.9 | 86 | 6.1 | 56 | 5.6 | 282 | 33.1 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white/other | 232 | 8.2 | 764 | 31.4 | 319 | 13.2 | 187 | 7.2 | 947 | 39.9 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 153 | 21.0 | 268 | 36.1 | 110 | 11.3 | 94 | 11.9 | 181 | 19.7 |

| Hispanic | 94 | 24.3 | 131 | 36.5 | 65 | 12.2 | 48 | 10.0 | 82 | 16.9 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Female | 309 | 10.1 | 818 | 34.7 | 293 | 11.2 | 201 | 7.1 | 760 | 37.0 |

| Male | 170 | 9.8 | 345 | 28.6 | 201 | 15.5 | 128 | 8.6 | 450 | 37.5 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| < high School | 199 | 14.5 | 385 | 38.6 | 112 | 13.0 | 83 | 6.6 | 196 | 27.3 |

| High school graduate | 154 | 8.9 | 434 | 33.3 | 184 | 12.5 | 110 | 6.6 | 408 | 38.7 |

| > high school | 126 | 6.7 | 344 | 24.6 | 198 | 13.6 | 136 | 9.8 | 606 | 45.3 |

| Metropolitan area | ||||||||||

| Yes | 394 | 9.9 | 920 | 31.2 | 414 | 13.7 | 280 | 8.0 | 991 | 37.2 |

| No | 85 | 10.2 | 243 | 35.7 | 80 | 10.5 | 49 | 6.4 | 219 | 37.3 |

| Health status | ||||||||||

| Self-rated health status | ||||||||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 338 | 10.0 | 842 | 30.9 | 366 | 12.7 | 260 | 8.7 | 913 | 37.6 |

| Fair/poor | 132 | 9.1 | 308 | 34.4 | 127 | 14.6 | 66 | 4.5 | 294 | 37.4 |

| Healthcare utilization | ||||||||||

| Recent doctor/other health provider visit | ||||||||||

| Yes | 326 | 7.5 | 1035 | 31.8 | 453 | 13.3 | 289 | 7.6 | 1155 | 39.8 |

| No | 150 | 28.1 | 124 | 35.1 | 40 | 11.5 | 40 | 8.9 | 49 | 16.5 |

Had a flu shot during the past flu season (i.e., between September 2003 and the date of the interview)

Ever had pneumonia shot

Had FOBT in the past year, sigmoidoscopy in the past 5 years, and/or colonoscopy in the past 10 years

Unweighted n

Weighted %

Associations between each demographic, health status, and healthcare utilization characteristic and each preventive services use category that were statistically significant at p < 0.05 are in bold.

CRC, colorectal cancer; FOBT, fecal occult blood test

In bivariate analyses, increasing respondent age was associated with greater likelihood of being current with vaccination only. Younger respondents were more likely to be current with CRC screening only or CRC screening and one of the vaccinations. Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks were more likely than non-Hispanic whites to lack currency with any of the preventive services, and less likely to be current with all three. Women were more likely than men to be current with one or both vaccinations but not CRC screening, and less likely to be current with CRC screening and one of the vaccinations. Greater educational attainment was associated with currency with all three preventive services, while the likelihood of not being current with any preventive service was lower among individuals with more education. A similar pattern was evident for individuals who reported a recent doctor/other health provider visit: they were more likely to be current with all three services and less likely to lack currency with any of them compared with individuals who did not have a recent visit. Respondents who rated their health as fair or poor were less likely to be current with CRC screening only.

Predictors of Preventive Services Use

In the polytomous logistic regression model shown in Table 3, currency with one or more of the preventive services was compared against not being current with any service. Having a recent doctor/other health provider visit was the only consistent predictor of currency with one or more of the services across all levels of the model. Being of non-Hispanic white race was a predictor of currency with all categories of preventive services use except CRC screening only. Having more than a high school education was a predictor of currency with CRC screening only as well as with all three services. Age was not a consistent predictor. Gender, location in a metropolitan statistical area, and self-rated health status did not predict preventive services use. The subsidiary analysis—conducted to assess determinants of currency with each preventive service separately—confirmed that being current with one service was predictive of currency with another (data not shown).

Table 3.

Polytomous logistic regression model showing predictors of preventive services use, 2004 National Adult Immunization Survey (n = 3632)

| Current with flua and/or pneumonia shotb but not CRC screening vs. not current with any of the 3 | Current with CRC screeningc and flu or pneumonia shot vs. not current with any of the 3 | Current with CRC screening only vs. not current with any of the 3 | Current with all 3 vs. not current with any of the 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Demographic | ||||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 65–69 | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- | ||

| 70–74 | 1.51 | 0.92–2.46 | 1.16 | 0.66–2.04 | 0.98 | 0.53–1.79 | 1.49 | 0.91–2.44 |

| 75–79 | 2.42 | 1.33–4.41 | 1.80 | 0.90–3.60 | 1.24 | 0.60–2.57 | 2.90 | 1.57–5.34 |

| 80+ | 1.55 | 0.95–2.53 | 0.33 | 0.18–0.62 | 0.54 | 0.27–1.11 | 0.88 | 0.53–1.45 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white/other | 2.53 | 1.50–4.25 | 3.38 | 1.81–6.32 | 1.65 | 0.79–3.44 | 5.73 | 3.28–10.01 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.02 | 0.57–1.83 | 0.92 | 0.43–1.98 | 1.17 | 0.53–2.62 | 1.11 | 0.57–2.17 |

| Hispanic | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- | --- | |||

| Male | 0.92 | 0.62–1.36 | 1.44 | 0.91–2.28 | 1.29 | 0.78–2.14 | 1.08 | 0.72–1.61 |

| Education | ||||||||

| < high school | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- |

| High school graduate | 1.27 | 0.80–2.01 | 1.28 | 0.71–2.29 | 1.48 | 0.77–2.83 | 1.39 | 0.99–1.95 |

| > high school | 1.33 | 0.79–2.23 | 1.77 | 0.96–3.26 | 2.84 | 1.46–5.52 | 1.92 | 1.37–2.69 |

| Metropolitan area | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- |

| No | 0.88 | 0.55–1.40 | 0.64 | 0.36–1.12 | 0.78 | 0.42–1.42 | 0.85 | 0.52–1.37 |

| Health status | ||||||||

| Self-rated health status | ||||||||

| Excellent/VG/good | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- |

| Fair/poor | 1.11 | 0.72–1.70 | 1.38 | 0.81–2.34 | 0.62 | 0.34–1.11 | 1.18 | 0.76–1.84 |

| Healthcare utilization | ||||||||

| Recent doctor/other health provider visit | ||||||||

| No | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- |

| Yes | 3.38 | 2.12–5.40 | 5.30 | 2.82–9.96 | 3.92 | 2.00–7.69 | 11.42 | 6.38–20.46 |

Had a flu shot during the past flu season (i.e., between September 2003 and the date of the interview)

Ever had pneumonia shot

Had FOBT in the past year, sigmoidoscopy in the past 5 years, and/or colonoscopy in the past 10 years

Multivariate associations that were statistically significant at p < 0.05 are in bold.

CI, confidence interval; CRC, colorectal cancer; FOBT, fecal occult blood test; OR, odds ratio

Reasons for Not Having a Flu Shot, Pneumonia Shot, or CRC Screening Tests

Reasons given for not having a flu shot, pneumonia shot, or CRC screening tests by respondents who were not current with these preventive services were similar for the pneumonia shot and CRC screening tests, but differed markedly for the flu shot (Table 4). The most frequently-cited reason for not having a flu shot was concern about the vaccine’s side effects (25%), followed by the belief that the vaccine wasn’t needed or not knowing that it was needed (23%). In contrast, the belief that the service wasn’t needed or not knowing that it was needed was the most common reason given for not having a pneumonia shot (47%) or CRC screening tests (44% for FOBT, 51% for sigmoidoscopy, 47% for colonoscopy). The doctor not recommending or ordering the service was the second most common reason for not having a pneumonia shot (20%) or CRC screening tests (21% FOBT, 26% sigmoidoscopy, 30% colonoscopy). This reason was mentioned by only 2% of respondents who were not current with the flu shot, however. Other reasons for not having flu shots or CRC tests were much less frequently cited.

Table 4.

Main reason for not having a flu shot, pneumonia shot, or colorectal cancer screening tests among respondents not current with these preventive services, 2004 National Adult Immunization Survey

| Immunizations | Colorectal cancer screening tests | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flu Shot (n= 588)

% 95% CI |

Pneumonia shot (n = 1244)

% (95% CI) |

FOBT (n = 602)

% (95% CI) |

Sigmoidoscopy (n = 587)

% (95% CI) |

Colonoscopy (n = 953)

% (95% CI) |

|

| Didn’t think it was needed/know I should have it | 22.6 (17.5–28.6) | 46.9 (42.2–51.6) | 43.9 (37.4–50.7) | 51.1 (44.6–57.5) | 47.0 (42.0–52.1) |

| Doctor didn’t recommend/order it | 2.4 (1.4–4.1) | 20.2 (16.6–24.5) | 21.4 (16.4–27.4) | 25.7 (20.7–31.4) | 29.7 (25.2–34.6) |

| Didn’t think about it/forgot | 6.0 (3.1–11.2) | 3.9 (2.4–6.1) | 5.8 (4.0–8.2) | 5.8 (3.2–10.5) | 4.3 (2.7–6.6) |

| Concerned about side effects, preparation, or discomfort | 25.1 (19.6–31.5) | 6.9 (4.8–9.8) | NA | 2.5 (1.2–5.2) | 2.9 (1.7–4.8) |

| Didn’t want to have it/perform the test | 7.6 (4.8–11.7) | 4.6 (2.8–7.4) | 3.9 (1.9–8.0) | 3.3 (1.6–6.4) | 3.9 (2.1–6.9) |

| Afraid of results/didn’t want to know results | NA | NA | 1.5 (0.5–4.3) | 2.1 (1.0–4.5) | 1.5 (0.8–2.7) |

| Costs too much | 0.6 (0.2–1.7) | 1.1 (0.3–3.7) | NA | 1.3 (0.4–4.6) | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) |

| Allergic to the vaccine | 8.5 (5.2–13.7) | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) | NA | NA | NA |

| Vaccine not effective | 7.0 (4.5–10.8) | 2.0 (1.1–3.4) | NA | NA | NA |

| Vaccine not available | 4.3 (2.3–8.0) | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | NA | NA | NA |

| Had office-based FOBT | NA | NA | 8.1 (4.8–13.2) | NA | NA |

| Other | 12.4 (8.7–17.2) | 6.9 (5.0–9.4) | 10.2 (6.5–15.7) | 5.8 (2.9–11.1) | 7.0 (4.6–10.4) |

| Don’t know/refused | 3.6 (1.8–6.8) | 6.9 (4.7–10.0) | 5.3 (3.1–8.8) | 2.5 (1.2–5.3) | 3.7 (2.3–6.1) |

FOBT = fecal occult blood testing, CI = confidence interval, NA = not applicable

DISCUSSION

This analysis of 2004 national survey data indicates modest increases in use rates by U.S. adults aged 65 and older of influenza vaccination (74%), pneumonia vaccination (64%), and CRC screening (58%) over the past few years.7,10,14 Data from the 2003 National Health Interview Survey showed that 56% of men and 49% of women aged 65+ were current with CRC screening;7 the 2003 NAIS documented that of individuals aged 65+, 68% were current with influenza vaccination and 60% with pneumonia vaccination.10 In this study, only about one-third of older adults were current with all three preventive services, and 10% were not current with any of them. That only 37% of older adults were current with all three recommended services is especially noteworthy because 88% of the study sample reported visiting a doctor or other health professional at least once during the nine months preceding the interview.

Having a recent provider visit was a strong and consistent predictor of preventive services use. In addition, being of non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity and having more than a high school education were predictors of currency with all three preventive services. In contrast, nearly one-quarter of Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks lacked currency with any of the services, compared with only 8% of non-Hispanic whites. Not knowing the service was needed and the doctor not recommending or ordering it were the most common reasons for not having a pneumonia vaccination or CRC screening tests. Concerns about side effects and not knowing the service was needed were the most common reasons for not having an influenza vaccination.

These findings highlight the need for improvements in delivery of preventive services to older adults. If all older adults reporting a recent provider visit had been offered and accepted the three preventive services, the proportion current with them would have more than doubled, perhaps even exceeding 85%. A high proportion of those who were current with influenza vaccination said they had received this service in a medically-related place, further emphasizing the importance of physician offices and clinics as delivery settings for preventive services in the 65 and older population. Primary care providers, however, face a number of barriers to delivering preventive services, including growing administrative burdens, lower reimbursement, and demands for brief visits.15 According to one national survey, one-quarter of primary care physicians lack the ability to generate lists of older patients who should receive influenza vaccinations, and three-quarters have never used reminders to prompt eligible patients that they are due for one.16 A more recent national survey indicates that information technology systems in physician offices are still used primarily for billing instead of capturing clinical information or communicating with patients.17 However, this is likely to change as over half of surveyed primary care physicians said they expected to adopt electronic medical records in the next 1–3 years, and nearly one-quarter indicated intent to start communicating with patients on-line.17

Strategies for achieving higher utilization of preventive services use in the older adult population should target both patients and providers. Activating patients to more proactively manage their own care has been shown to improve compliance and outcomes related to treatment as well as prevention.18 Educational efforts that inform older adults of recommended preventive services may foster more active engagement in their own health management.

Furthermore, because older adults tend to see a provider on a regular basis, orienting practices to systematically check for and offer recommended preventive services is key to improving utilization. Standing orders programs have been promoted as an effective means of increasing influenza and pneumonia vaccination rates in primary care practices,19 and may also have utility in increasing CRC screening with FOBT.20 The “Welcome to Medicare” physical exam, a Medicare benefit implemented in 2005, provides an excellent opportunity for new Medicare beneficiaries and their providers to discuss several preventive services, including influenza and pneumonia vaccinations and CRC screening.21 “Bundling” multiple preventive services at a single encounter is effective in increasing preventive services use.22,23 Evidence reviews and recommendations for ways to increase use of vaccines and CRC screening are summarized in the Guide to Community Preventive Services.24

There are limitations to this study. Although the 2004 NAIS provided a rich source of information on immunization and CRC screening use, only limited information about respondents’ socioeconomic and health status characteristics—including health care coverage—was obtained. Respondents were aged 65+, and an estimated 97% of this population is covered by Medicare.25 Nevertheless, some respondents may have been underinsured or uninsured.

Variation in preventive services use by coverage type—including among the Medicare population—has been documented.6,26 The 2004 NAIS was conducted by telephone, and a response rate of 51.4% obtained. Although this response rate is comparable to that of other large telephone surveys27–29 and a nonresponse adjustment was used in the analysis, nonrespondents may have differed from respondents along characteristics that could not be measured. Finally, respondents’ self-reports of preventive services use may have been inaccurate. Some studies have shown patient reports of influenza and pneumonia vaccination and CRC screening tests to be reasonably accurate, though.30–34

Rates of influenza and pneumonia vaccination and CRC screening among older Americans are suboptimal. This is especially apparent when examining the combined use of these services. Although patient and provider activation and the new “Welcome to Medicare” benefit are among the strategies that may improve use of these services, broader policy efforts may be necessary to substantially improve preventive services delivery.18 Such efforts could include support for a national health information infrastructure, pay-for-performance initiatives, and medical education. Ongoing monitoring and further research are required to determine the most effective approaches.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tim McNeel of Information Management Services, Inc., Silver Spring, MD, for expert programming assistance. The data upon which this article is based were collected under an inter-agency agreement (#Y1-PC-4037) between the National Cancer Institute and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

No financial conflict of interest was reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice, American Academy of Family Physicians. General recommendations on immunization. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51 (RR2):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:129–131. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh JM, Terdiman JP. Colorectal cancer screening: scientific review. JAMA. 2003;289:1288–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon CR, Lapin PJ. A government perspective: if there is so much proof, why is Medicare not rapidly adopting health promotion and disease prevention programs? Am J Health Promot. 2001;15:383–387. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-15.5.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maciosek MV, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, Flottemesch TJ, Goodman MJ, Solberg LI. Priorities among effective clinical preventive services: results of a systematic review and analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fielding JE, Long PV. A Better Medicare for Healthier Seniors—Recommendations to Modernize Medicare’s Prevention Policies. Washington, DC: Partnership for Prevention; 2003. Increasing use of clinical preventive services among Medicare beneficiaries. Available at: www.prevent.org/publications/medicare.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meissner HI, Breen N, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:389–394. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lees KA, Wortley PM, Coughlin SS. Comparison of racial/ethnic disparities in adult immunization and cancer screening. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shenson D, Bolen J, Adams M, et al. Are older adults up-to-date with cancer screening and vaccinations? Prev Chronic Dis. 2005 Jul; [serial online] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2005/jul/05_0021.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Singleton JA, Santibanez TA, Wortley PM. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination of adults aged > 65: racial/ethnic differences. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hebert PL, Frick KD, Kane RL, McBean AM. The causes of racial and ethnic differences in influenza vaccination rates among elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:517–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00370.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen JY, Diamant A, Pourat N, Kagawa-Singer M. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of preventive services among the elderly. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith PJ, Battaglia MP, Huggins VJ, et al. Overview of the sampling design and statistical methods used in the National Immunization Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20 (4S):17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu PJ, Singleton JA, Rangel MC, Wortley PM, Bridges CB. Influenza vaccination trends among adults 65 years or older in the United States, 1989–2002. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1849–1856. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.16.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Blumenthal D. Changes in career satisfaction among primary care and specialist physicians, 1997–2001. JAMA. 2003;289:442–449. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis MM, McMahon SR, Santoli JM, Schwartz B, Clark SJ. A national survey of physician practices regarding influenza vaccine. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:670–676. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manhattan Research. Taking the Pulse v5.0: Physicians and Emerging Information Technologies. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salinsky E. National Health Policy Forum Issue Brief No. 806. Aug 24, 2005. Clinical preventive services: when is the juice worth the squeeze? [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notice to readers: facilitating influenza and pneumococcal vaccination through standing orders programs. MMWR Weekly. 2003;52:68–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarfaty M. National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable. 2005. What You Should Know About Screening for Colorectal Cancer: A Primary Care Clinician’s Evidence-Based Toolbox and Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeWilde LF, Russell C. The “Welcome to Medicare” physical: a great opportunity for our seniors. [Accessed on March 13, 2006];CA Cancer J Clin. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.6.292. Available at: http://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/content/full/54/6/292. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Shenson D, Cassarino L, DiMartino D, et al. Improving access to mammograms through community-based influenza clinics: a quasi-experimental study. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:97–102. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shenson D, Quinley J, DiMartino D, Stumpf P, Caldwell M, Lee T. Pneumococcal immunizations at flu clinics: the impact of community-wide outreach. J Community Health. 2001;26:191–201. doi: 10.1023/a:1010321128990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaza S, Briss PA, Harris KW. The Guide to Community Preventive Services: What Works to Promote Health? New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(supplement):IV-3–IV-18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potosky AL, Breen N, Graubard BI, Parsons PE. The association between health care coverage and the use of cancer screening tests: results from the 1992 National Health Interview Survey. Med Care. 1998;36:257–270. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199803000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hepner KA, Brown JA, Hays RD. Comparison of mail and telephone in assessing patient experiences in receiving care from medical group practices. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:377–389. doi: 10.1177/0163278705281074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson DE, Powell-Griner E, Town M, Kovar MG. A comparison of national estimates from the National Health Interview Survey and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1335–1341. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keeter S, Miller C, Kohut A, Groves RM, Presser S. Consequences of reducing nonresponse in a national telephone survey. Public Opin Q. 2002;64:125–148. doi: 10.1086/317759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shenson D, DiMartino D, Bolen J, Campbell M, Lu PJ, Singleton JA. Validation of self-reported pneumococcal vaccination in behavioral risk factor surveillance surveys: experience from the sickness prevention achieved through regional collaboration (SPARC) program. Vaccine. 2005;23:1015–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacDonald R, Baken L, Nelson A, Nichol KL. Validation of self-report of influenza and penumococcal vaccination status in elderly outpatients. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16:173–177. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon NP, Hiatt RA, Lampert DI. Concordance of self-reported data and medical record audit for six cancer screening procedures. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:566–570. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.7.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hiatt RA, Perez-Stable EJ, Quesenberry C, Sabogal F, Otero-Sabogal R, McPhee SJ. Agreement between self-reported early cancer detection practices and medical audits among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white health plan members in northern California. Prev Med. 1995;24:278–285. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandelson MT, LaCroix AZ, Anderson LA, Nadel MR, Lee NC. Comparison of self-reported fecal occult blood testing with automated laboratory records among older women in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:617–621. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]