Abstract

Background

Research has not established (1) if breast cancer screening varies by county-level-proportion of uninsured or (2) whether county-level-proportion of uninsured correlates with county-level early-stage and late-stage breast cancer incidence.

Methods

A multilevel study was conducted to determine if individual-level self-reported breast cancer screening data from the 2000 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) was associated with county-level-proportion–uninsured data from the 1999–2001 BRFSS. An ecologic study was conducted to determine if county-level proportion of uninsured correlated with incidence of early-stage and late-stage breast cancer using the 1999–2001 BRFSS data from the overlapping counties in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Data were analyzed in 2005.

Results

Women were less likely to be screened (prevalence odds ratio: 0.95; 95% confidence interval=0.93–0.97) with every 5% increasing county-level proportion of uninsured. African-American and Hispanic women who resided in counties with a proportion of uninsured of 9%–19% had higher screening utilization than white non-Hispanic women. The county-level-proportion of uninsured had little effect on screening use among women with household incomes less than $25,000 or greater than $75,000. Screening prevalence decreased with increasing county-level proportion of uninsured among women with intermediate income. The rate of T1 (<2 cm diameter) tumors decreased with increasing county-level proportion of uninsured while controlling for poverty rate; Spearman correlation −0.294.

Conclusions

High county-level proportions of uninsured may lead to lower early-stage breast-cancer incidence through lower screening use among women living in these less-well-insured counties.

Introduction

Lack of health insurance coverage is a significant barrier to obtaining adequate health care and can lead to negative health outcomes. People without health insurance have poorer health outcomes after illness and have higher overall mortality rates.1,2 Compared with insured people, those without insurance are less likely to have a usual source of care and are less likely to seek care when they feel they need it. When hospitalized, uninsured people receive fewer services, are more likely to receive substandard care, and are at greater risk of dying during a hospital stay or soon after discharge than insured patients.3,4

Over the past 25 years, the number of Americans without health insurance has increased steadily. An estimated 42 million Americans under age 65 lacked healthcare coverage in 2004.5 Lack of insurance has especially affected minority populations. In 2004, 32.5% of Hispanics lacked health insurance, a far greater proportion than that of the non-Hispanic African-American (16.1%) and non-Hispanic white (10.4%) populations.5

While uninsured people clearly face significant barriers to health care, the health of all residents in communities with a high proportion of uninsured people may be compromised, as suggested by the Institute of Medicine (IOM).6 High community percentage of uninsured may hamper the opportunities for insured as well as uninsured residents to obtain health care, due to cutbacks or the removal of available services and longer waiting times to receive services. These barriers to access may reduce the health of all members of the community, but the impact may be greater among vulnerable populations (e.g., low income, uninsured, racial minorities) who live in communities with higher percentages of uninsured,6–9 although few studies have examined this.

Because primary and preventive services are often considered elective by patients, the use of these services is expected to fall off more quickly when patients lack the financial means to pay for medical care. Several studies have shown that the uninsured and people with low incomes are less likely to receive preventive and screening services, including screening for cancer, compared to people with health insurance or higher incomes.10–12 As a result, people without insurance and with low incomes are more likely to be diagnosed with cancers at a more advanced stage.13,14 However, it is unclear if the use of preventive services, such as cancer screening services, is correlated with the level of insurance coverage in a particular geographic area6 and not just insurance coverage at the level of the individual. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to determine if screening for breast cancer varied by community- (i.e., county-) proportion of uninsured specifically among vulnerable populations, who might be disproportionately affected. In addition, the correlations between county-level proportion of uninsured and county early-stage and late-stage breast cancer incidence were calculated.

Methods

The current study consisted of two related parts. First, a multilevel study was conducted using the public-use Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data to determine if individual-level self-reported screening in the 2000 BRFSS data was associated with county-level proportion of uninsured from 1999–2001 BRFSS data. Second, an ecologic study was performed with county as the unit of analysis to determine if the county-level proportion of uninsured from the 1999–2001 BRFSS data was correlated with incidence of early-stage and late-stage breast cancer using the 1999–2001 public-use data from the overlapping counties in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Data were analyzed in 2005.

Data from BRFSS

During 1999–2001, all states included a question in the BRFSS interview about survey participants' county of residence. For confidentiality purposes, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) did not release the county of residence for counties with fewer than 50 participants. Therefore, the analyses were based on data for counties with a minimum of 50 respondents aged 18 or older. There were 43,529 women aged 40 years or older from 658 counties available for analysis using the 2000 BRFSS. This represented 20.4 % of all counties and 63.8 % of all women aged 40 years or older participating in the entire United States 2000 BRFSS.

Screening Assessment

The use of mammography and clinical breast examination (CBE) was assessed by questions in the 2000 BRFSS inquiring about ever having had a mammogram/CBE and about the time since the last mammogram/CBE. Women aged 40 years or older who had both a mammogram and a CBE within 1 year before their telephone interview were compared to all other women aged 40 or older.

Women's Characteristics

Andersen's behavioral and access to care model15 was used to identify women's characteristics to determine if the effect of county-level proportion of uninsured could be explained by characteristics of women previously identified as being associated with screening use, including insurance coverage, household income, educational attainment, race/Hispanic ethnicity, self-perceived health, age, cost as a barrier to medical care, and smoking status. These characteristics were obtained from the 2000 BRFSS data.

County-Level Proportion of Uninsured

The 1999–2001 BRFSS data for all respondents aged 18–64 years irrespective of gender were used to determine the percentage of uninsured people in each county, since Medicare coverage is nearly universal among persons aged 65 or older. Three years of data were used to increase the stability of the proportion uninsured for each county, with an average of 391 respondents aged 18–64 per county (range: 50 to 6089). County-level proportion of uninsured was used as a continuous variable in the statistical models.

Breast Cancer Clinical Outcomes

The ecologic study used 1999–2001 SEER data. Indicators of breast cancer screening from the SEER data that have been shown to be precursors to reductions in mortality include higher incidence of in-situ breast cancer, T1 tumors, lower incidence of stage II–IV tumors, and locally advanced (T3 and T4) breast cancer.16 In-situ breast cancer was identified from the fifth digit of the histology-behavior code, which is based on the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. T1 tumors were those less than 2 cm in maximum diameter. Stage II–IV cancers were based on the American Joint Commission on Cancer classification (excluding those with unknown stage). The fourth group were tumors classified as T3 (tumors more than 5.0 cm in greatest diameter) or T4 (any size tumor with direct extension to the chest wall or skin, and inflammatory carcinoma).17 Denominator information for the calculation of rates per 100,000 population was based on 1999–2001 census data. Women who were aged 40 years or older and diagnosed with primary breast cancer were included. A total of 86 counties were contained in both the SEER and available BRFSS data.

Statistical Analysis

The multilevel models were all three-level models in which individuals (Level 1) were nested within counties (Level 2), which were nested within states (Level 3). The multilevel logistic model involved second-order Taylor series.18 Restricted Iterative Generalized Least Squares (RIGLS) estimation was used for model fitting.19 The multilevel analysis was performed using MLwiN 2.0.20 Parameters in the fixed part were tested with the Wald test.21 Parameters in the random part were tested using the Wald test and Likelihood ratio test.21 Prevalence odds ratios (POR) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. The POR is the ratio of the odds of adhering to breast cancer screening guidelines in the group of interest compared with the reference group. Three interactions were tested after all individual-level variables were added to the model using the Wald statistic: (1) county-level proportion of uninsured and respondent race, (2) county-level proportion of uninsured and household income, and (3) county-level proportion of uninsured and individual-level insurance status. The Akaike Information Criterion was used as an indicator of model fit. A lower value indicated better fit.

All multilevel analyses involved weighted estimation of model parameters. Individual-level weights were those provided by BRFSS, adjusted for probability of inclusion in the sample, and representative of the sample by gender, age, and racial/ethnic stratum. County-level weights were based on 2000 census county population. State level weights were based on the sum of county populations of included counties.

For the ecologic study, partial Spearman rank-order correlation coefficients determined the associations between county-level proportion of uninsured and the incidence rates of each of the four clinical outcomes from the SEER data at the county level while controlling for the county poverty rate. County poverty rate was found to be one of the key indicators of the socioeconomic status of counties.22, 23 Since for some counties, the number of breast cancers was very low (thereby making the incidence rates unstable), the analyses were limited to counties with at least ten cases of each of the four indicators.

Results

Multilevel Study

Figure 1 displays the location of counties that were included in the analysis and county-level proportion of uninsured. Included counties tended to (1) have a lower percentage of its residents living below the federal poverty level, (2) have more residents per square mile, (3) be more likely to be part of a metropolitan area, and (4) have a higher percentage of African Americans than counties that were not included in the analysis (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Map of counties included in the multilevel analysis by county-level proportion uninsured.

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics of counties included and not included in the multilevel analysis

| Counties included in analysis (n=658) | Counties not included in analysis (n=2561) | All counties in the U.S. (n=3219) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (minimum–maximum) | Median (minimum–maximum) | p value | Median (minimum–maximum) | |

| Percent of families below federal poverty line | 8.2% (1.6–45.1) | 10.1% (0.0–64.1) | 0.163 | 9.7% (0.0–64.1) |

| Population density (residents per square mile) | 146.8 (1.7–45,519.3) | 35.1 (0.0–5646.7) | <0.001 | 42.0 (0.0–45,519.3) |

| In metropolitan area | 61.3% | 19.4% | <0.001 | 28.0% |

| Percent African American | 3.1% (0.0–67.1) | 1.5% (0.0–86.1) | 0.010 | 1.8% (0.0–86.1) |

The county-level proportion of uninsured ranged from 3% to 54 %, although only six counties had a county-level proportion of uninsured of 30 % or more (Table 2). The percentage of white non-Hispanic women decreased with increasing county-level proportion of uninsured. The percentage of women with household incomes of less than $25,000, without healthcare coverage, and who reported cost to be a barrier to receiving medical care all increased with increasing county-level proportion of uninsured (Table 2).

Table 2.

Population characteristics by grouped county-level proportion uninsured

| County-level proportion uninsured (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.0–9.9 | 10.0–19.9 | 20.0–29.9 | 30.0+ | |

| Number of counties | 186 | 369 | 97 | 6 |

| Number of women age 40 or older Age (years)a | 14,980 | 25,074 | 4815 | 171 |

| 40-49 | 35.2 | 33.8 | 34.5 | 38.6 |

| 50-59 | 26.2 | 25.6 | 26.1 | 23.0 |

| 60-69 | 18.0 | 18.7 | 18.9 | 16.3 |

| 70 and older | 20.4 | 21.9 | 20.4 | 22.2 |

| Race/Hispanic ethnicitya | ||||

| White, nonHispanic | 86.3 | 74.3 | 50.7 | 28.6 |

| African American, nonHispanic | 7.4 | 13.3 | 18.1 | 1.5 |

| Other nonHispanic | 2.5 | 3.7 | 6.7 | 2.3 |

| Hispanic | 3.7 | 8.8 | 24.6 | 67.6 |

| Household incomea | ||||

| < $25,000 | 19.5 | 27.0 | 35.7 | 39.5 |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 25.8 | 27.7 | 24.0 | 27.2 |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 16.1 | 13.6 | 11.3 | 5.3 |

| ≥$75,000 | 20.4 | 14.1 | 13.3 | 8.3 |

| Unknown | 18.2 | 17.6 | 15.8 | 19.7 |

| Health insurance coveragea | ||||

| Yes | 95.7 | 91.6 | 86.0 | 70.7 |

| No | 4.3 | 8.4 | 14.0 | 29.3 |

| Cost as barrier to medical carea | ||||

| Yes | 5.6 | 9.5 | 12.2 | 29.8 |

| No | 94.4 | 90.5 | 87.8 | 70.2 |

p<0.001

During 2000, 62.1% of women 40 and older reported that they had a mammogram and a CBE during the past year. Women were 0.91 as likely to be screened (95% CI: 0.88–0.93) with every 5% increase in county-level-proportion of uninsured. After adding the individual-level characteristics, including health insurance coverage, to this model, women remained less likely to be screened (POR=0.95; 95% CI=0.93–0.97) with increasing county-level proportion of uninsured over and above the women's characteristics, including health insurance coverage (Table 3). Of the total variance, 0.4 % (p<0.05) remained at the state level, but no county-level variance was present after adding all variables (p>0.05).

Table 3.

Results of the multilevel logistic regression models, the second model adjusted for interactions

| Variable | Model 1 Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Model 2 Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| County-level proportion uninsured (per 5%) | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) |

| Race/Hispanic ethnicity | ||

| African American, nonHispanic | 1.32 (1.24–1.42) | 1.06 (0.73–1.55) |

| Other, nonHispanic | 0.43 (0.39–0.47) | 1.00 (0.62–1.61) |

| Hispanic | 1.29 (1.20–1.38) | 1.59 (0.74–3.40) |

| White, nonHispanic | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Household income | ||

| <$25,000 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 1.26 (1.19–1.33) | 1.50 (1.13–1.99) |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 1.43 (1.33–1.54) | 2.21 (1.66–2.96) |

| ≥$75,000 | 1.93 (1.79–2.08) | 1.95 (1.57–3.98) |

| Unknown | 1.42 (1.33–1.51) | 1.27 (0.85–1.88) |

| Health insurance coverage | ||

| No | 0.42 (0.39–0.46) | 0.42 (0.33–0.53) |

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Education | ||

| 8th grade or less | 0.64 (0.58–0.70) | 0.63 (0.51–0.78) |

| 9th–11th grade | 0.75 (0.69–0.81) | 0.72 (0.61–0.85) |

| At least 12th grade | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 40-49 | 0.66 (0.69–0.62) | 0.65 (0.61–0.69) |

| 50-59 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 60-69 | 0.94 (0.88–1.01) | 0.93 (0.85–1.01) |

| 70 and older | 0.72 (0.67–0.76) | 0.70 (0.58–0.86) |

| Cost as barrier to medical care | ||

| Yes | 0.65 (0.61–0.70) | 0.65 (0.54–0.79) |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Daily or occasional smoker | ||

| Yes | 0.75 (0.71–0.79) | 0.75 (0.63–0.89) |

| Never smoked | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| County-level proportion of uninsured (per 5%)—race interaction | ||

| African American, nonHispanic | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) | |

| Other, nonHispanic | 0.79 (0.76–0.81) | |

| Hispanic | 0.94 (0.89–0.98) | |

| White, nonHispanic | 1.00 | |

| County-level proportion of uninsured (per 5%)—household income interaction | ||

| <$25,000 | 1.00 | |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 0.94 (0.93–0.96 | |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 0.87 (0.86–0.89) | |

| ≥$75,000 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | |

| Akaike Information Criterion | 56881 | 56814 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

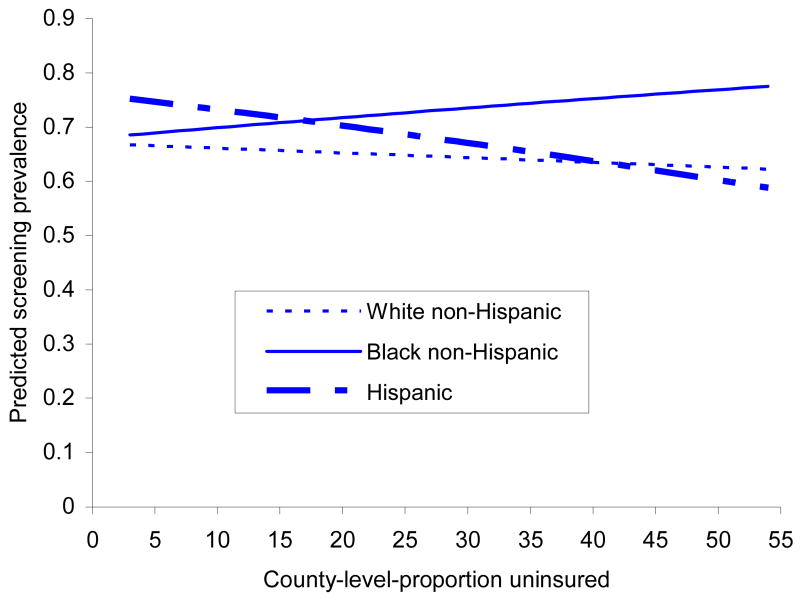

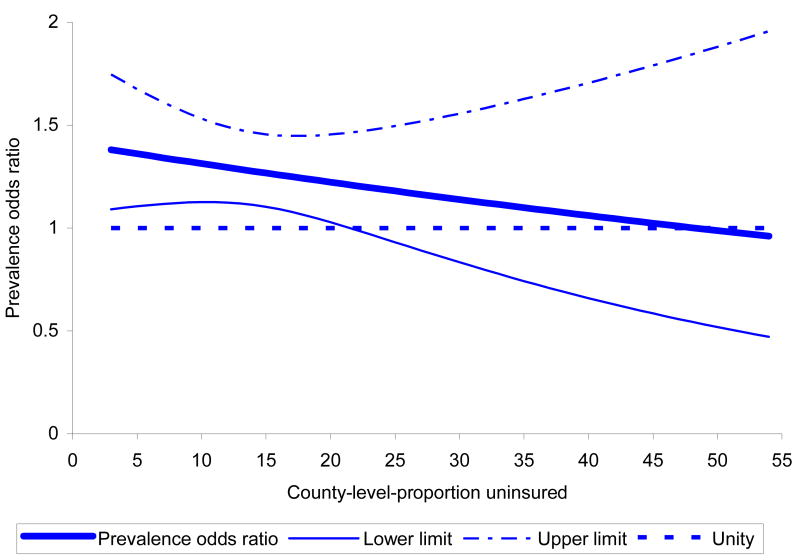

The effect of county-level proportion of uninsured was dependent on race/Hispanic ethnicity and household income (both p<0.001), but not by a woman's insurance coverage (p=0.280).Predicted screening prevalence was relatively similar among the three racial/ethnic groups when county-level proportion of uninsured was low (Figure 2), but was unaffected by county-level proportion uninsured for white non-Hispanic women. For African-American non-Hispanic women, predicted screening prevalence increased slightly, while among Hispanic women, prevalence declined with increasing county-level-proportion uninsured. African-American non-Hispanic women who resided in counties with proportion uninsured of 9%–19 % had slightly higher screening utilization than white non-Hispanic women in these counties based on the exclusion of the value of one from the 95% CI. While the likelihood of screening among Hispanic women declined with increasing county-level proportion of uninsured, in counties with county-level proportion of uninsured between 9% and 18 %, Hispanic women had higher screening utilization relative to white non-Hispanic women.

Figure 2.

Predicted breast cancer screening prevalence for three racial/ethnic groups by county-level proportion uninsured, controlling for individual-level variables.

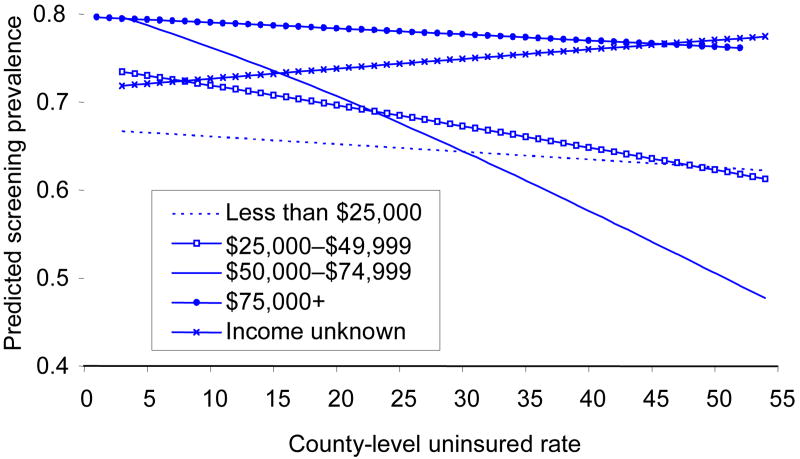

At low county-level proportion of uninsured, predicted screening prevalence for women with annual household incomes of less than $25,000 was lower relative to those with higher incomes (Figure 3). For women with incomes less than $25,000 and incomes $75,000 or more, screening prevalence declined slightly with increasing county-level proportion of uninsured. Among the two middle-income groups, there was a steeper decline in screening prevalence with increasing county-level proportion of uninsured. Screening prevalence declined more steeply with higher county-level proportion of uninsured among women with household incomes of $50,000–$74,999 than among other women. Among women with incomes of $25,000–$49,999, screening prevalence was higher relative to women with household incomes of less than $25,000 at low county-level proportion of uninsured, but was similar at higher county-level proportion of uninsured. These findings remained in adjusted analysis. Supplemental material can be found in the online appendix (www.ajpm-online.net).

Figure 3.

Predicted breast cancer screening prevalence for five income groups by county-uninsured rate, controlling for individual-level variables.

Ecologic Study

There were 9596 in-situ breast cancers, 25,275 T1 tumors, 2874 T3 and T4 tumors, and 19,487 stage II–IV cancers among all women from the counties that were represented in both the SEER and BRFSS data. Table 4 shows that the rate of T1 tumors decreased with increasing county-level proportion of uninsured while controlling for poverty rate (partial correlation=−0.294). The partial correlations between county-level proportion of uninsured and the rates of in-situ, T3/T4, or stage II–IV tumors were not statistically significant.

Table 4.

Partial Spearman correlations (p values) between 1999–2001 county-level proportion uninsured and 1999–2001 incidence of four clinical indicators of breast cancer screening among women age 40 or older, controlling for poverty ratea

| In-situ | T1 tumor | T3 & T4 tumor | Stage II–IV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # counties | 59 | 80 | 43 | 78 |

| Mean # cases per county (min–max) | 152 (10–956) | 300 (10–2110) | 63 (10–344) | 238 (10–1794) |

| County rate (min–max) | 17.9–68.7 | 45.2–182.2 | 10.1–28.9 | 53.8–135.5 |

| Partial correlation (p value) | –0.248 (0.060) | –0.294 (0.0086) | –0.142 (0.3490) | –0.177 (0.1229) |

Number of cancers per county in each category ≥10.

Discussion

County-level proportion of uninsured was independently associated with breast cancer screening. Thus, county-level proportion of uninsured not only affects access to specialty care and hospital-based care6 but also affects behaviors, such as breast cancer screening. Although the POR was only slightly below unity, the importance of this finding is reflected in the large number of women who are affected. Thus, some contextual effect of county-level proportion of uninsured appeared to be present and was not mediated by the available individual-level variables. Other individual-level variables not available in the BRFSS might explain the association.

The association between county-level proportion of uninsured and breast cancer screening depended on the race/ethnicity and household income of women. African-American non-Hispanic women and Hispanic women had higher screening utilization when residing in counties with a proportion of uninsured of 9%–19 % relative to white non-Hispanic women. Although this appears to be a narrow range of the proportion of uninsured, this range accounted for 70.0% of the sample included (data not shown).

Recent data have shown a higher prevalence of mammography use among African-American relative to white women.24 This study extends these recent results and suggests that this increased use may be limited to counties with a proportion of uninsured of 9%–19%.

The association between screening and county-level proportion of uninsured also varied by household income. For women with the highest and lowest household incomes, the predicted screening prevalence did not vary by county-level-proportion of uninsured. In contrast, while screening use among women with the household incomes in the $50,000–$74,999 range was two times higher at the lowest county-level proportion of uninsured (3%) compared with women with the lowest incomes, the prevalence of screening did not differ significantly between these two income groups when residing in counties with a county-level proportion of uninsured of 22 % or more. Similar findings were observed for women with incomes of $25,000–$49,999 and for women with incomes of $50,000–$74,999, although predicted screening prevalence was lower for residents of counties with a low proportion of uninsured people.

The association between county-level proportion of uninsured and screening among women with the highest and lowest household incomes was likely the result of two different mechanisms. Women with the lowest incomes may rely disproportionately on so-called safety-net providers in counties with a high proportion of uninsured people. Particularly for low-income residents and members of other medically underserved groups, clinics and health centers play a special role in primary healthcare services delivery. The results for low-income women could partly be explained by their participation in the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP),25 although only about 13% of eligible women participated nationally.26 Others have hypothesized that differences in access may reflect the economic makeup of the uninsured person's community.6 Community wealth may significantly affect service delivery in areas with a higher proportion of uninsured. Providers in wealthier areas may be better able or inclined to deliver free or reduced-price care.9

For women with the highest household incomes, the county-level proportion of uninsured was not associated with screening. These women likely had the economic means to obtain screening regardless of where they resided, having the means to seek medical care outside their county if it had a high proportion of uninsured persons and limited availability of services.

Breast cancer screening among women with incomes of $25,000–$74,999 was most affected by high county-level proportion of uninsured. Predicted screening prevalence among women with incomes of $50,000–$74,999 declined dramatically even for small increases in county-level proportion of uninsured. This may be the result of difficulty of obtaining health care due to cutbacks or removal of available services and longer waiting times.6 Unlike low-income women, women with incomes of $50,000–$74,999 are unlikely to be eligible for services typically provided through public-sponsored safety-net providers, such as the NBCCEDP.

The multilevel results were confirmed in the ecologic study. While controlling for county-level poverty rates, counties with a higher proportion of uninsured people showed lower early-stage breast cancer incidence rates (significantly lower for T1 tumors). Due to the small number of women with in-situ tumors living in counties with higher proportion of uninsured persons, this association only approached significance (Table 4). The lack of an association with late-stage breast cancer can be expected since screening does not affect these types of cancers until several years after affecting early-stage cancers.27

There were several limitations to this study. First, generalizability was limited to only 658 of the 3219 U.S. counties that were included in the BRFSS data analysis. Counties that were included in the analysis were typically located in metropolitan areas, had higher population density, a higher percentage of African Americans, and a lower poverty rate. Second, income was unknown for 17.6% of women included in the analysis. However, differences in individual-level characteristics between women for whom income was known and unknown were quite small and not meaningful.

Third, county-level proportion of uninsured data were obtained from the 1999–2001 BRFSS, whereas the individual-level characteristics were obtained from the 2000 BRFSS. If persons over- or under-estimated their insurance also over- or under-estimated their screening use, then bias might be differential and away from the null.28 By using 1999–2001 BRFSS data about county-level proportion of uninsured from both genders and all U.S. up to age 65 and only 2000 data for individual-level insurance status, overlap between the number of people who reported on screening and insurance was relatively small (11.7%). Therefore, any bias away from the null is expected to be small.

Fourth, since the BRFSS interviews were conducted by telephone, county-level proportion of uninsured was constructed from the responses of people who had telephones. Because people without telephones are more likely to have lower incomes, and therefore more likely to be uninsured, the observed association between self-reported county-level proportion of uninsured and breast cancer screening is likely underestimated.

Conclusions

Women residing in counties with a high proportion of uninsured persons had lower breast cancer screening utilization, which was especially pronounced among women with incomes between $25,000 and $75,000 and among Hispanic women. High county-level proportion of uninsured in association with lower early-stage breast cancer incidence could lead to poorer breast health outcomes for all women living in these less-well-insured counties.

Future research should examine further the mechanisms by which county-level proportion uninsured affects breast cancer screening particularly among women with household incomes of $25,000–$75,000 and racial/ethnic minority women beyond factors included in the models. Policymakers need to continue to propose methods for making health insurance more available to all members of U.S. communities. Studies should then evaluate the effect of expanding insurance coverage on access to care as well as population health.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri, for the use of the services of the Health Behavior and Outreach Core, especially for data management and statistical services provided by Mr. Jim Struthers.

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA91842, CA91734, CA98594, CA10712, P30 CA91842) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HS 14095-01).

Appendix

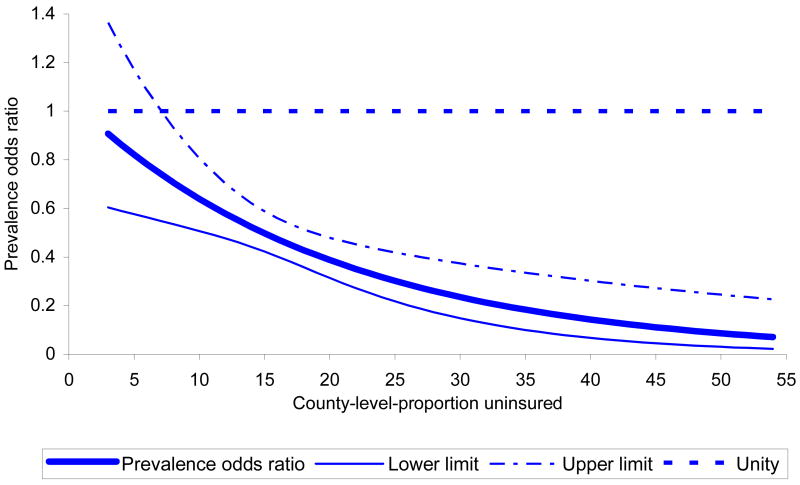

Figure A-1.

Adjusted prevalence odds ratios (95% CI) of breast cancer screening of African-American non-Hispanic versus white non-Hispanic women by county-level-proportion of uninsured.

Figure A-2.

Adjusted prevalence odds ratios (95% CI) of breast cancer screening of other non-Hispanic versus white non-Hispanic women by county-level-proportion of uninsured.

Figure A-3.

Adjusted prevalence odds ratio (95% CI) of breast cancer screening of Hispanic versus white non-Hispanic women by county-level-proportion of uninsured.

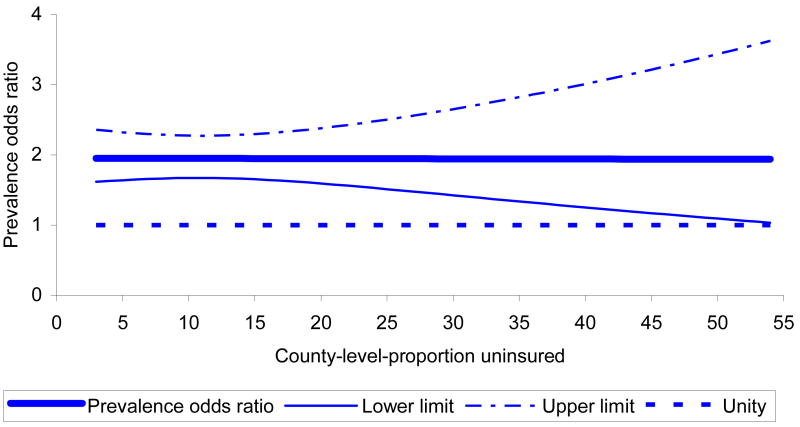

Figure A-4.

Adjusted prevalence odds ratio (95% CI) of breast cancer screening for women with household incomes of ≥$75,000 versus those with incomes of <$25,000 by county-level-proportion of uninsured.

Figure A-5.

Adjusted prevalence odds ratio (95% CI) of breast cancer screening for women with household incomes of $50,000–$74,999 versus those with incomes of <$25,000 by county-level-proportion of uninsured.

Figure A-6.

Adjusted prevalence odds ratio (95% CI) of breast cancer screening for women with household incomes of $25,000–$49,999 versus those with incomes of <$25,000 by county-level-proportion of uninsured.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ayanian JZ, Kohler BA, Abe T, Epstein AM. The relation between health insurance coverage and clinical outcomes among women with breast cancer. New Engl J Med. 1993;329:326–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307293290507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canto JG, Rogers WJ, French WJ, Gore JM, Chandra NC, Barron HV. Payer status and the utilization of hospital resources in acute myocardial infarction: a report from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2. Arch Intl Med. 2000;160:817–23. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burstin HR, Lipsitz SR, Brennan TA. Socioeconomic status and risk for substandard medical care. JAMA. 1992;268:2383–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas JS, Goldman L. Acutely injured patients with trauma in Massachusetts: differences in care and mortality, by insurance status. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1605–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.10.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Center for Health Statistics. With chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville MD: GPO; 2005. Health, United States, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine. A shared destiny. Community effects of uninsurance. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham PJ, Kemper P. Ability to obtain medical care for the uninsured. How much does it vary across communities? JAMA. 1998;280:921–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown E, Wyn R, Teleki S. Disparities in health insurance and access to care of residents across U S cities. Los Angeles CA: Regents of the University of California; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen RM, Yu H, Wyn R, Davidson PL, Brown ER, Teleki S. Access to medical care for low-income persons: How do communities make a difference? Med Care Res Rev. 2002;59:384–411. doi: 10.1177/107755802237808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iezzoni LI, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Siebens H. Mobility impairments and use of screening and preventive services. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:955–61. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.6.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schootman M, Fuortes LJ. Breast and cervical carcinoma: The correlation of activity limitations and rurality with screening, disease incidence, and mortality. Cancer. 1999;86:1087–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michielutte R, Dignan MB, Smith BL. Psychosocial factors associated with the use of breast cancer screening by women age 60 years or over. Health Educ Behav. 1999;26:625–47. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Ginsburg JA, Zaslavsky AM. Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA. 2000;284:2061–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roetzheim RG, Pal N, Tennant C, et al. Effects of health insurance and race on early detection of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1409–15. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.16.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Social Behavior. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Day NE, Williams DRR, Khaw KT. Breast cancer screening programmes: the development of a monitoring and evaluation system. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:954–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. 5th. Philadelphia PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldstein H, et al. Multilevel statistical models. 2d. London: Edward Arnold Publishers; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldstein H. Restricted unbiased iterative generalized least-squares estimation. Biometrika. 1989;76:622–3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasbash J, Browne W, Healy M, Cameron B, Charlton C, et al. MLwiN Beta Version 2.0. London: Multilevel Models Project, Institute of Education, University of London; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hox JJ. Multilevel analysis of grouped and longitudinal data. In: Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J, editors. Modeling longitudinal and multilevel data. Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh G, Miller B, Hankey B, Edwards B. Area socioeconomic variations in U S cancer incidence, mortality, stage, treatment, and survival, 1975–1999. Bethesda MD: National Cancer Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV. Race/ethnicity, gender, and monitoring socioeconomic gradients in health: a comparison of area-based socioeconomic measures--the public health disparities geocoding project. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1655–71. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones AR, Caplan LS, Davis MK. Racial/ethnic differences in the self-reported use of screening mammography. J Community Health. 2003;28:303–16. doi: 10.1023/a:1025451412007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eheman E, Benard V, Blackman D, et al. Breast cancer screening among low-income or uninsured women: Results from the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Pogram, July 1995 to March 2002 (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:29–38. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-4558-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tangka F, Dalaker J, Chattopadhyay S, et al. Meeting the mammography screening needs of underserved women: the performance of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program in 2002–2003 (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:1145–54. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0058-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schootman M, Jeffe DB, Reschke AH, Aft R. The full potential of breast cancer screening to reduce mortality has not yet been realized in the United States. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;85:219–22. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000025410.41220.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lask TL, Fink AK. Neighborhood environment and loss of physical function in older adults: Evidence from the Alameda County study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:472–3. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]