Abstract

Lung surfactant secretion in alveolar type II cells occurs following lamellar body fusion with plasma membrane. Annexin A7 is a Ca2+-dependent membrane-binding protein that is postulated to promote membrane fusion during exocytosis in some cell types including type II cells. Since annexin A7 preferably binds to lamellar body membranes, we postulated that specific lipids could modify the mode of annexin A7 interaction with membranes and its membrane fusion activity. Initial studies with phospholipid vesicles containing phosphatidylserine and other lipids showed that certain lipids affected protein interaction with vesicle membranes as determined by change in protein tryptophan fluorescence, protein interaction with trans membranes, and by protein sensitivity to limited proteolysis. The presence of signaling lipids, diacylglycerol or phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate, as minor components also modified the lipid vesicle effect on these characteristics and membrane fusion activity of annexin A7. In vitro incubation of lamellar bodies with diacylglycerol or phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate caused their enrichment with either lipid, and increased the annexin A7 and Ca2+-mediated fusion of lamellar bodies. Treatment of isolated lung lamellar bodies with phosphatidylinositol- or phosphatidylcholine phospholipase C to increase diacylglycerol, without or with preincubation with phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate, augmented the fusion activity of annexin A7. Thus, increased diacylglycerol in lamellar bodies following cell stimulation with secretagogues may enhance membrane fusion activity of annexin A7.

Keywords: Membrane Fusion, surfactant secretion, protein fluorescence, proteolysis, membrane insertion, membrane binding, signaling lipids

Lung surfactant is essential for normal lung function in air-breathing mammals because it is required for lowering surface tension at the air-liquid interface during end-expiration (reviewed in [1, 2]). This lipoprotein-like complex of phospholipid and proteins is synthesized and secreted by the alveolar type II cells (reviewed in [3]). The phospholipid and some of the protein components are stored in lamellar bodies, the secretion organelles unique to type II cells. Surfactant secretion occurs through fusion pores that are formed following lamellar body fusion with plasma membrane (reviewed in [4, 5]). Several studies have demonstrated that several agents increase surfactant secretion in isolated perfused lung and in isolated type II cells by increasing cell Ca2+, cAMP, and protein kinase C (PKC) activity [4, 5]. Some of these agents also increase the number of surface fusion pores suggesting that the membrane fusion activity is increased to allow elevated secretion of surfactant [6, 7].

Previous studies have suggested a role for annexin proteins in membrane fusion during surfactant secretion [8–10]. Annexin A7 is postulated to promote membrane fusion during exocytic secretion in some cell types [8, 11]. We have previously demonstrated that annexin A7 could promote membrane fusion between isolated lamellar bodies and lung plasma membrane fractions [9], or increase surfactant secretion in semi-intact type II cells [8]. Annexin A7 binding to lamellar bodies is higher than to the plasma membrane or the cytosol fraction [12] suggesting that the lamellar body membrane characteristics could contribute to the higher binding. Although annexin A7 binding protein was detected in both the lamellar bodies and the plasma membrane fractions [12], the lipids in the lamellar body membrane could also contribute to annexin A7 binding. This study also showed that the protein binding to lamellar bodies and plasma membrane can be further enhanced followed cell treatment with calcium ionophore or phorbol myristate acetate (a direct activator of PKC). Since intracellular membranes show differences in lipid composition [13–16], it is also likely that these differences contribute to specificity and membrane binding and fusion activities of annexin A7.

Annexin A7, like other annexin proteins, binds to phospholipid membranes in a Ca2+-dependent manner through the highly homologous COOH- (core) domain (reviewed in [17–19]). The unique NH2- (tail) terminus is short for most annexin proteins except for annexin A7 and A11 that have long tails. The unique nature of the NH2-terminus is postulated to contribute to specificity of annexin function [20]. Several previous studies employing annexin A5 as a model annexin protein have demonstrated high affinity binding to acidic phospholipid like phosphatidylserine (PS) or phosphatidic acid (reviewed in [17]). This is also supported by the presence of postulated PS binding sequences in the annexin molecule [21]. Even though PS binding sites are present in the core domain, our studies with recombinant wild type and deletion mutant annexin A7 proteins suggest that the NH2-terminus could modify the core domain and its Ca2+-dependent interaction with phospholipid vesicle (PLV) membranes [22]. Although annexin proteins bind poorly to major membrane phospholipids like phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) [17], a comparison of the Ca2+-dependent binding of annexin A7 and its mutants to PC:PS (3:1) and PE:PS (3:1) PLV indicated that change in major lipid could influence annexin A7 interaction with membranes [23]. Further, annexin A7 preferably binds to specific biological membranes [12, 24–26] alluding to the possibility that the membrane lipid composition could have a role in affecting protein interaction with these membranes. Others have demonstrated [27–29] preferred binding of annexin A2 to specific cellular membranes like plasma membrane or to phospholipid vesicles (PLV) enriched with phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). This important phospholipid is also implicated in the action of synaptotagmin, a Ca2+-binding synaptic vesicle protein, which showed preference for PIP2-containing domains in membranes [30]. These observations suggest that other phospholipid species (besides PS) could also control protein interaction with membranes. Such regulation of protein binding by specific lipid could contribute to site-specific physiological regulation of protein function [14, 16], since significant differences in phospholipid composition of intracellular membranes have been reported [13–16]. Another possible implication of observations with annexin A2 and synaptotagmin lies in the involvement of PIP2 in the signal transduction pathways (reviewed in [31–33]), since its hydrolysis by phospholipase C (PLC) would generate inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) that increase cell Ca2+and protein kinase C (PKC) activity, respectively. In alveolar type II cells, as in most other cell types, Ca2+ and PKC are implicated in stimulation of secretion by exocytosis [34–37]. Thus, modulation of annexin A7 properties by DAG or PIP2 would suggest that stimulation of cells with appropriate secretagogues would regulate annexin A7 function for augmented secretion.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that the PIP2 and DAG levels would significantly modulate the properties of annexin A7, since increased membrane fusion activity would be needed in type II cells stimulated with surfactant secretagogues [34–37]. We utilized PLV prepared from various lipid mixtures to show that lipid composition, PIP2 and DAG in particular, affected the molecular characteristics (protein fluorescence and protease sensitivity) and the membrane fusion function of annexin A7. In parallel, altering the PIP2 or DAG content in isolated lung lamellar bodies modulated the membrane binding and membrane fusion activities of annexin A7. We propose that these signaling lipids in biological membranes could contribute to the specificity of annexin A7 action and regulation of membrane fusion during surfactant secretion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

L-α-phosphatidylcholine (brain), L-α-phosphatidylserine (Brain, bovine), L-α-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (brain, Porcine), 1,2,dioleoylglycerol, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine-N-(5-dimethylamino-1-naphthalenesulfonyl) (dansylPE, DPE), and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) and were used without further purification. Recombinant trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) was used to cleave recombinant fusion protein for the release of free annexin A7. Chymotrypsin, PC-PLC, PI-PLC, cholesterol and other fine chemicals were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Polyclonal antibodies to PIP2 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). All standard chemicals and glassware were from VWR Scientific (Rochester, NY) unless indicated otherwise. Silica gel G coated thin layer chromatography plates were by Whatman Inc and obtained from Fisher Scientific (Philadelphia, PA). Recombinant annexin A7 protein was expressed in E. coli as described [22]. The purified protein was stored in small aliquots at −70° C in 50mM Tris-Acetate-1mM EGTA (TAE) buffer (pH 8.3).

Preparation of Phospholipid Vesicles

Lipid mixtures of indicated composition in chlroform:methanol (20:1, v/v) were evaporated to dryness under a stream of N2. The dried lipids were suspended by vortexing in TAE buffer and passed through a membrane extruder (LIPEX, Northern Lipids, Inc., Vancouver, Canada) fitted with a 100 nm filter to prepare lipid vesicles. Lipid suspensions were passed (x4) through a 200 nm filter and then (x4) through the 100 nm filter. The passage of lipid suspension through the filter causes formation of lipid vesicles of approximately 100 nm in diameter. The vesicle suspension was stored at 4° C and brought to experimental temperature before use. If any small unilamellar vesicles (<30 nm) were present, they would spontaneously fuse to form larger vesicles during storage at 4° C, which may be below the phase transition temperature of vesicle lipid mixtures.

Isolation of lamellar bodies

Lungs of anesthetized (Nembutal, 50mg/Kg, ip) and exsanguinated male Sprague-Dawley rats (~200g) were ventilated and cleared of residual blood by perfusion through the pulmonary artery with phosphate buffered saline containing 10 mM glucose. The visibly cleared lungs were instilled with sucrose (1M, unbuffered), harvested, and homogenized in 1M sucrose. Lamellar bodies from lung homogenate (10%) were isolated by upward flotation on a discontinuous sucrose density gradient, as described previously [38]. We routinely recover approximately 80–100 μg protein from one rat. We have previously shown in several studies that thus isolated lamellar bodies from lungs or type II cells show good homogeneity and purity as determined by electron microscopy and biochemical characterization [12, 25, 38, 39]. The isolated lamellar bodies were used for the binding and membrane fusion studies.

Lamellar body enrichment with PIP2 and DAG

Isolated lamellar bodies were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with either suspension of 100% PIP2 or DAG, or PLV containing PC:PE:PS:Cholesterol and PIP2 or DAG (42.5:17.5:25:10:5) and 10μM Ca2+ in 0.2 M sucrose in 50mM TAE buffer (pH 7.4). Following incubation, the lamellar bodies were separated by centrifugation for 10 min at 14,000rpm, washed twice with TAE-sucrose containing 10 μM Ca2+, and evaluated for the membrane fusion activity. Aliquots of thus incubated lamellar bodies were analyzed for PIP2 by dot blot analysis using a polyclonal PIP2 antibody (1:1000 dilution). The lipid of lamellar bodies were extracted [40] and analyzed for DAG by thin layer chromatography on silica gel G plates. The lipids were identified after exposure to I2 vapors and by co-migration with authentic lipids.

Tryptophan Fluorescence Studies

Protein tryptophan fluorescence of Annexin A7 was measured as described previously [22]. Triplicate fluorescence spectra of about 1 μM protein in TAE buffer (pH 8.3) were obtained in the absence or presence of 20 μM PLV. Fluorescence was measured first in the absence of Ca2+ and then in the presence of indicated concentrations of Ca2+ by sequential addition of 100 mM CaCl2 to provide the calculated free Ca2+ [41]. Calcium electrode was used to verify 5 μM or higher (up to 100 μM) Ca2+. All fluorescence results were corrected for dilutions, and emission due to buffer or other additions.

Proteolysis Studies

Trypsin or chymotrypsin proteolysis was performed for 1 or 4 h at 37° C. The reaction mixture (30 μl) contained 265.6 μg/ml annexin A7, and 6.56 μg/ml trypsin (15 units/μg protein) or 0.66 μg/ml chymotrypsin (81 units/mg protein), and indicated concentrations of PLV without or with 1mM Ca2+ in TAE buffer (pH 8.3). The protease reaction was stopped with the addition of appropriate amounts of loading buffer for SDS-PAGE. The proteins were resolved by electrophoresis, and quantified by photo imaging of Coomassie blue-stained gels using co-run recombinant annexin A7 as standard. In some experiments, proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes, stained with Coomassie blue and relevant protein bands were excised for N-terminal sequence analysis, which was performed by Edman degradation (Procise Protein Sequencer, Applied Biosystems, Inc.) at the Iowa State University Protein Sequence facility.

Lamellar Body Binding of Annexin A7

All binding studies were conducted by co-sedimentation assay as described previously [22]. Briefly, the lamellar bodies (7 μg protein) without or with incubation for enrichment with DAG or PIP2 (see above) were washed and incubated for 10 min at room temperature with 10 μg annexin A7 and 10 μM Ca2+ in TAE buffer in 200 μl total volume. The binding reaction was stopped by centrifugation (10 min at 14,000 rpm), the lamellar body pellet was washed (x2, each with 200 μl followed by centrifugation as described above) with the incubation buffer containing appropriate amounts of Ca2+, and the bound annexin A7 quantified after separation on SDS-PAGE and photo imaging of the Coomassie blue-stained gels. Protein binding to PLV containing DAG or PIP2 was assayed by similar protocol in which 45 μM PLV was used in place of lamellar bodies.

Membrane Fusion

Change in transfer efficiency of resonance energy due to lipid mixing was used as a measure of fusion between PLV or lamellar bodies with labeled PLV containing NBD-PE and Rh-PE, the donor and acceptor molecules for resonance energy, as described previously [25]. The reaction mixture (1.5 ml) contained 2 μM labeled PLV (PC:PE:PS:NBD-PE:Rh-PE, 65:10:25:0.75:0.75) and unlabeled 40 μM PLV of indicated composition, or 30 μg lamellar body protein. Changes in fluorescence of the reaction mixture were measured as a function of time after each addition. The fusion reaction was initiated with the addition of 10 μM Ca2+ and fluorescence monitored for 10 min. The reaction was terminated by adding 1% Triton X-100 to obtain maximum dilution of the probe. The fluorescence change during 10 min was expressed as percent of maximum (after addition of Triton X-100).

Other analyses

Proteins were quantified by the protein-dye binding assay according to Bradford [42] using bovine-γ-globulin as standard.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison between experimental and control groups were performed by Student’s t test for paired or unpaired observations, as appropriate. ANOVA was performed for comparison within multiple groups, which was followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test for comparison between two groups. P value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Tryptophan Fluorescence Studies

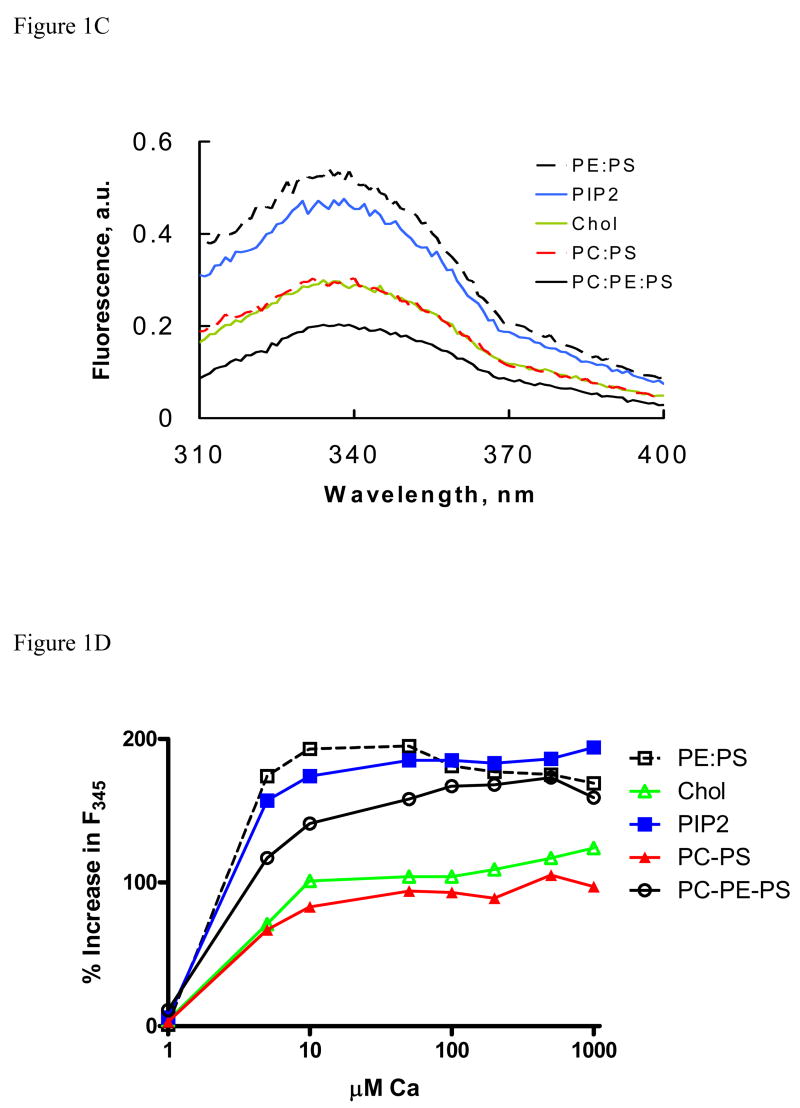

Our initial studies were aimed to determine if membrane lipid composition would affect molecular organization of annexin A7. Our previous studies with annexin A7 and its deletion mutants showed that the presence of PLV significantly modified the Ca2+-dependent increase in protein fluorescence, which occurs possibly due to molecular reorganization and the position of its tryptophan residue relative to other residues that can quench fluorescence [22, 23]. In the present study, we evaluated if PLV composition would affect Ca2+-dependent changes in protein fluorescence. The protein and phospholipid concentrations were kept low to ensure negligible inner filter effect on fluorescence. None of the PLV affected the protein fluorescence without calcium. The addition of 0.1mM Ca2+ without PLV caused a slight increase in fluorescence (not shown; [22]). However, in the presence of 20 μM PLV (PC:PS, 3:1), Ca2+ caused a large increase in protein fluorescence (Fig. 1A). The emission due to PLV was unaffected with Ca2+. Substitution of PC with PE in these PLV caused greater increase in fluorescence suggesting that the two lipids differentially influenced molecular organization and the tryptophan residue in annexin A7. Figure 1B shows fluorescence changes upon addition of 0.1 mM Ca2+ in presence of different PLVs and figure 1C shows dependence of fluorescence change on Ca2+ concentrations achieved with sequential additions of 100 mM Ca2+. The increase in fluorescence with PC:PE:PS (2:1:1) PLV, which was tested since biological membranes contain PC and PE in about 2:1 ratio, was intermediate between those seen with PC:PS (3:1) and PE:PS (3:1) (Fig. 1B and C). In this experiment, the protein concentration was half (20μg/ml, ~0.5 μM) of that used with other PLV. The fluorescence increases with Cholesterol-PLV (PC:PE:PS:cholesterol, 45:20:25:10) and PC:PS (3:1) were similar. Interestingly, the presence of 5% PIP2 in cholesterol-PLV caused a large increase that was equivalent to that seen with PE:PS (3:1). Similar change in fluorescence was observed with cholesterol-PLV containing 5% DAG (not shown). In order to facilitate comparison amongst different PLV, the increase is expressed as percent of fluorescence without Ca2+ (Fig. 1D). The increase was maximum with PE:PS (3:1) and minimum with PC:PS (3:1) PLV. Thus, these studies clearly suggested that the lipid composition of membranes affected the molecular organization of the protein and that minor components like PIP2 or DAG can significantly affect protein interaction with membranes.

Figure 1.

PLV composition affects annexin A7 protein fluorescence. A. Emission spectra for indicated PLV (20 μM) without (solid line) or with (broken line) 0.1 mM Ca2+. B. Fluorescence spectra are shown for ~ 1 μM annexin A7 with indicated additions. The spectra were obtained before and after addition of 20 μM PLV and then after addition of 0.1 mM Ca2+. The Ca2+–dependent increase in protein fluorescence was greater with PE:PS (◇) in comparison to that with PC:PS (▲). C. Fluorescence spectra of annexin A7 (40 μg/ml) in presence of indicated PLV (20 μM) and 0.1 mM Ca2+ are shown. The spectra were unaffected by PLV without Ca2+. In experiment with PC:PE:PS, the annexin A7 concentration was ~0.5 μM. D. The change in annexin A7 fluorescence at 345 nm (F345) with 20 μM vesicles and various concentrations of Ca2+ is expressed as percent of F345 without Ca2+. For all studies, the PLV composition was PC:PS, 3:1; PE:PS, 3:1; PC:PE:PS, 2:1:1;PC:PE:PS:Cholesterol, 45:20:25:10; and PC:PE:PS:Cholesterol:PIP2, 42.5:17.5:25:10:5. These experiments were replicated at least once with similar results. All results were corrected for emission changes due to buffer, PLV, or dilutions.

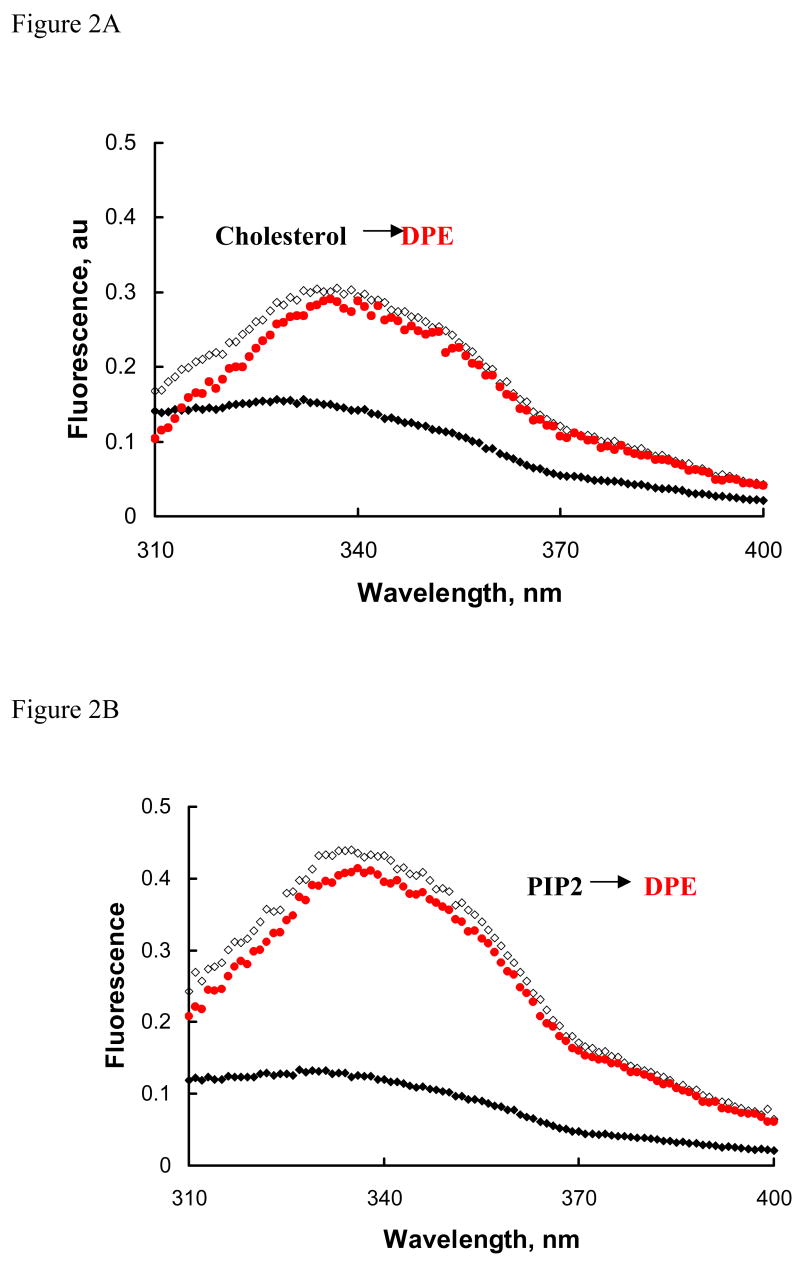

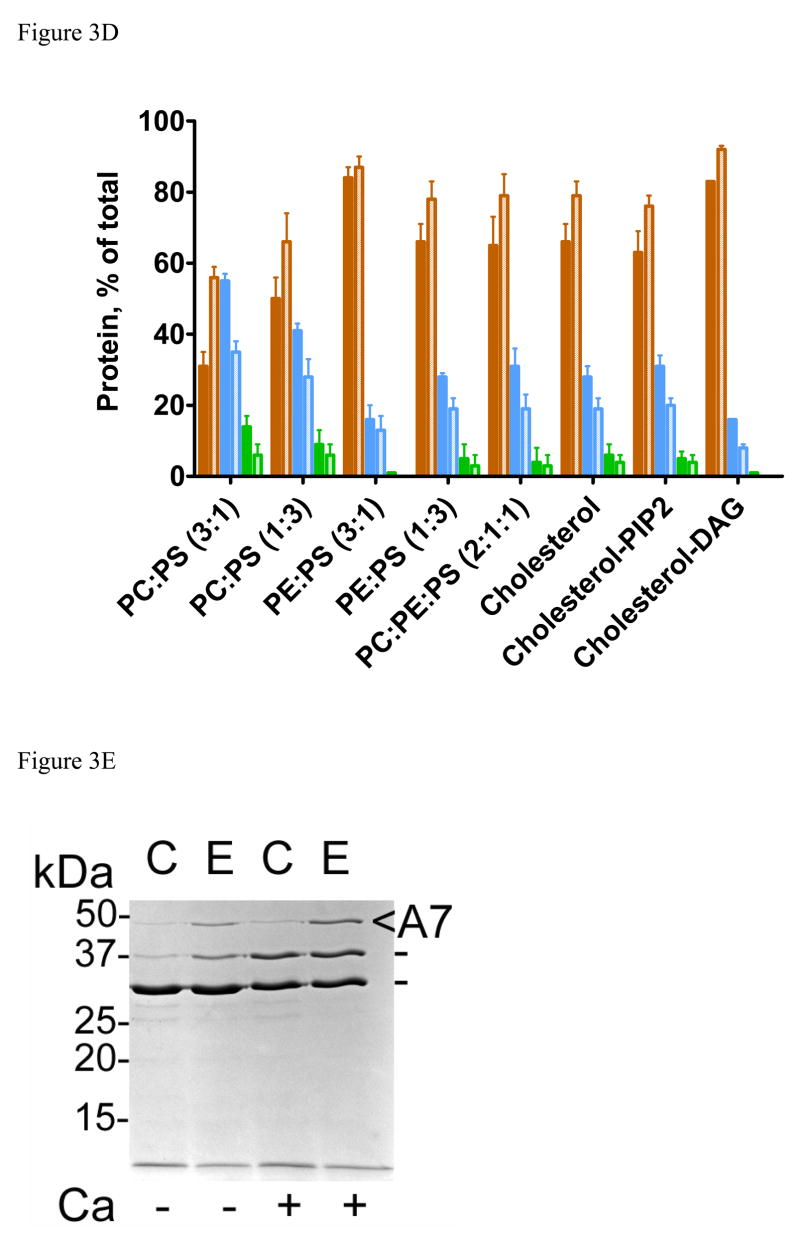

Membrane domains enriched with PIP2 are postulated as sites for interaction and membrane insertion for some proteins [27–30]. Modified lipids, like dansylPE (DPE), that act as acceptors of energy transfer and quench the fluorescence of reporter (tryptophan) residue in close vicinity have been used to demonstrate membrane insertion of the reporter into vesicle membranes [30]. Next, we exploited the protein fluorescence quenching with DPE as an indicator of change in molecular organization. In these studies, the Ca2+-dependent change in protein fluorescence was measured in the presence of one PLV (20 μM) and then after addition of similar concentration of second PLV. The cholesterol-PLV composition for these studies was PC:PE:PS:Cholesterol (45:20:25:10). The composition of PLV containing 5% lipid X (PIP2, DAG, or DPE) was PC:PE:PS:Cholesterol:X (42.5:17.5:25:10:5). In presence of cholesterol-PLV, Ca2+ (0.1mM) increased the protein fluorescence by 97% (Fig. 2A), which was reduced by only 3% with DPE-PLV. Similar experiments with PIP2-PLV (Fig. 2B) and DAG-PLV (Fig. 2C) showed respective increases of 272% and 140% with Ca2+ that were decreased by 7% and 13%, respectively, after addition of DPE-PLV. In comparison, Ca2+ increased the fluorescence only by 39% with DPE-PLV, which was further increased to 64% with PIP2-PLV (Fig. 2D). These observations suggest that 1) annexin A7 could form bridge between trans membranes of different lipid compositions, and 2) the protein could insert into membranes of specific lipid composition. The presence of DAG in membranes could facilitate such membrane insertion of the protein.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence quenching studies with dansyl phosphatidylethanolamine (DPE) demonstrate annexin A7 interaction with trans membranes. Corrected fluorescence spectra for annexin A7 (~1 μM) are shown before (filled symbol) and after the addition of 0.1 mM Ca2+ (open symbols) in the presence of 0.02 mM PLV of indicated composition (black). The second spectrum (red) was acquired after addition of the second PLV in the same fluorescence cuvette. The basic composition for all PLV was PC:PE:PS:Cholesterol (45:20:25:10) indicated as Chol. The other PLV contained PC:PE:PS:Cholesterol:X (42.5:17.5:20:10:5), where X was PIP2, DAG, or DPE. All experiments were repeated at least once with similar results. A. Cholesterol-PLV followed by DPE-PLV, B. PIP2-PLV followed by DPE-PLV, C. DAG-PLV followed by DPE-PLV, and D. DPE-PLV followed by PIP2-PLV.

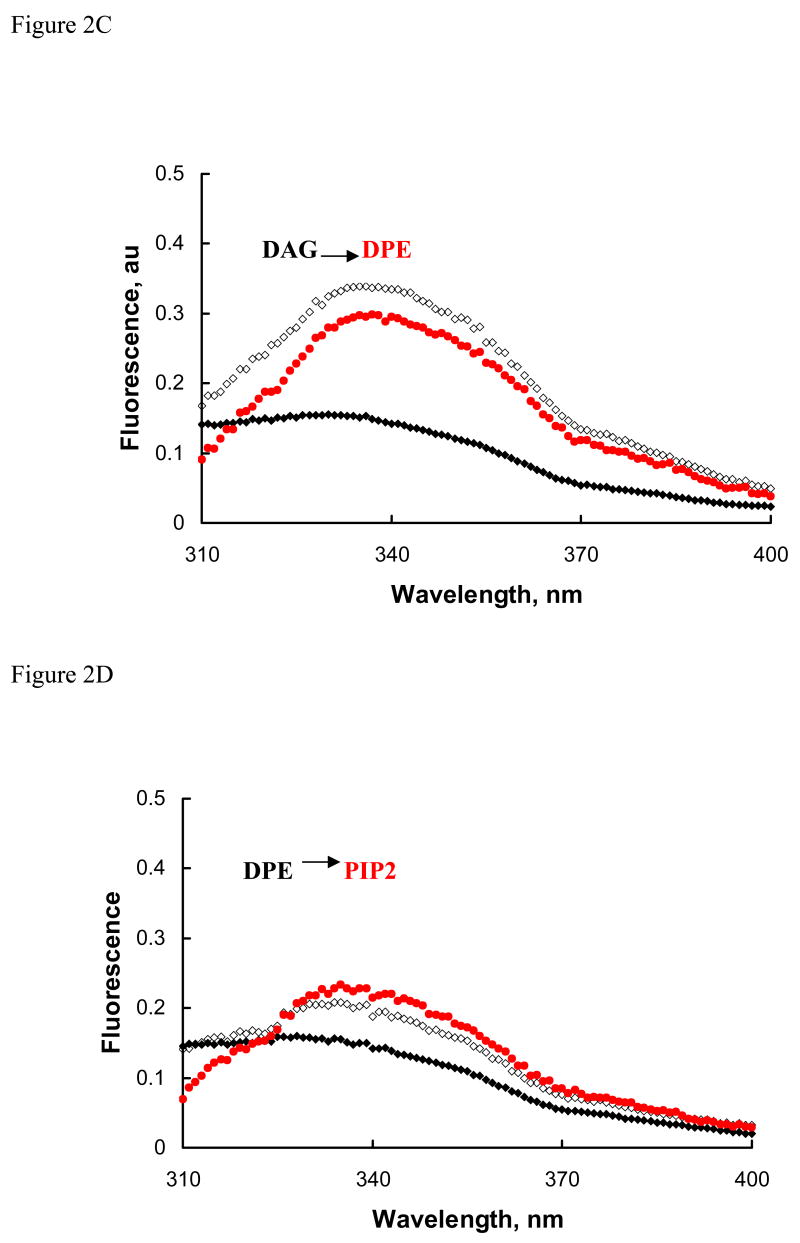

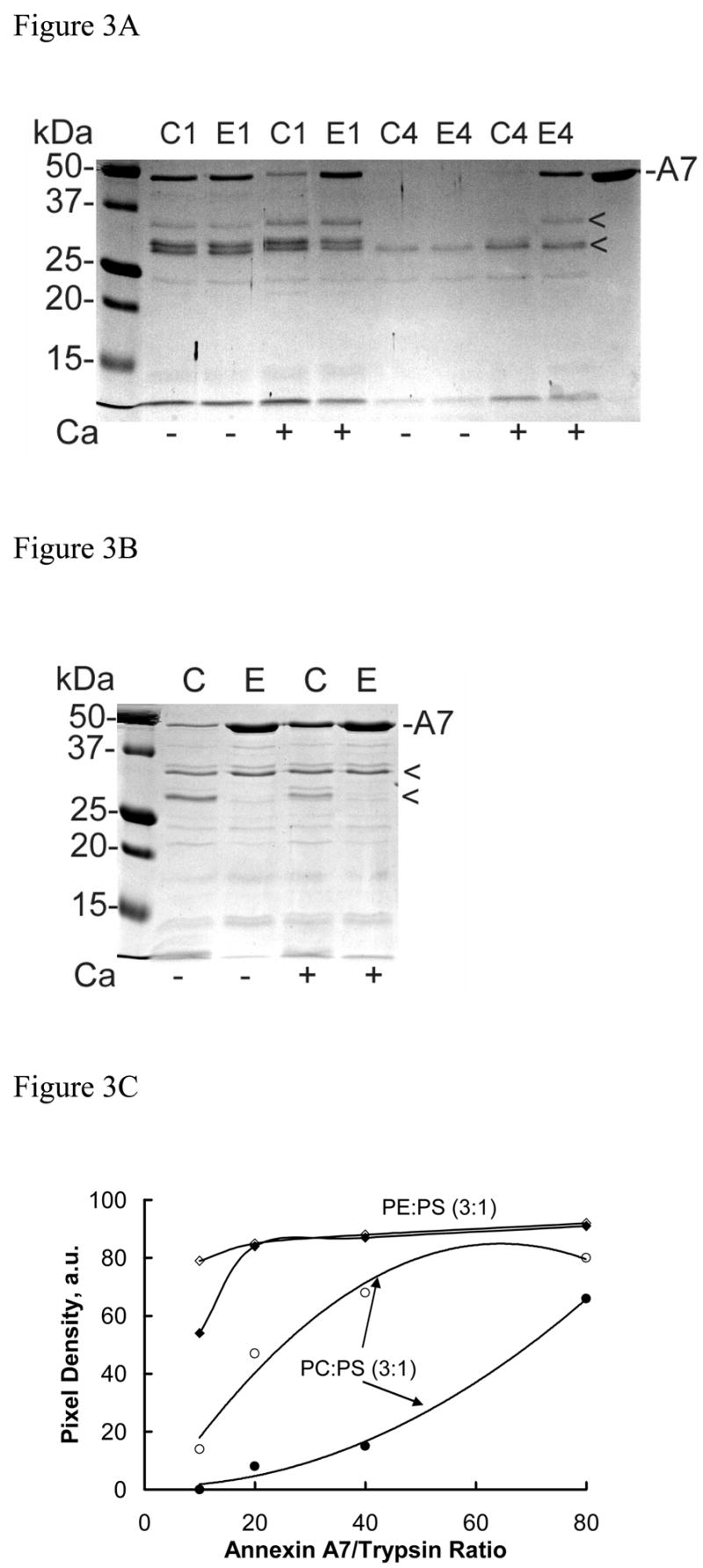

Proteolysis of Annexin A7 – Protease-specific Protection by Phospholipid

Annexin A7 contains several potential sites for trypsin and chymotrypsin enzymes. We have previously shown that the presence of PLV protects against trypsin proteolysis possibly by restricting access to the enzyme sites by masking them or by modifying the protein molecular organization [22]. Here we evaluated if the lipid composition of PLV affected the protection against trypsin and chymotrypsin. In the presence of PC:PS (3:1), the presence of 1mM Ca2+ increased trypsin proteolysis of annexin A7 during 1h incubation at 20 μM PLV (Fig 3A). At higher concentrations of PLV and during both 1 and 4h incubations, trypsin proteolysis was lower in presence of Ca2+ (not shown). During the 4h proteolysis in presence of 0.2 mM PC:PS (3:1), two major products at 28, and 33kDa were detected in the absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 3B, arrowheads). In comparison, trypsin proteolysis was lower with 0.2 mM PE:PS (3:1) and showed greatly diminished formation of 28kDa peptide. While Ca2+ did not provide additional protection with PE:PS (3:1), except at high trypsin concentration, its additional protective effect was apparent with PC:PS (3:1) at all annexin A7 to trypsin ratios and was near maximum at a ratio of 40 (Fig. 3C). Subsequent studies were undertaken at annexin A7 to trypsin ratio of 40 and at 0.2 mM PLV with varying compositions (Fig. 3D). Trypsin proteolysis in the presence of DAG-PLV was lower than that with cholesterol-PLV or PIP2-PLV and was similar to that with PE:PS (3:1). In all cases, the Ca2+-dependent protection against trypsin was reflected in decreased appearance of the 33kDa and 28kDa peptides (Fig. 3D) suggesting that the effect was due to lipid interaction with the parent protein and not with its degradation product. Examination of the proteolysis pattern did not reveal any new major peptide, suggesting that all types of PLV protected against the same site. The only notable difference was in the amounts of 28kDa peptide since its relative proportion was much lower when proteolysis was performed in presence of DAG-PLV or PE:PS (3:1). Thus, cell stimulation and degradation of PIP2 to generate IP3 (for increased Ca2+) and DAG would cause decreased accessibility of trypsin sites suggesting further modification of the annexin A7 molecule. These results suggest that protein interaction with specific phospholipid domains in biological membranes would modify annexin A7 conformation and possibly regulate protein function.

Figure 3.

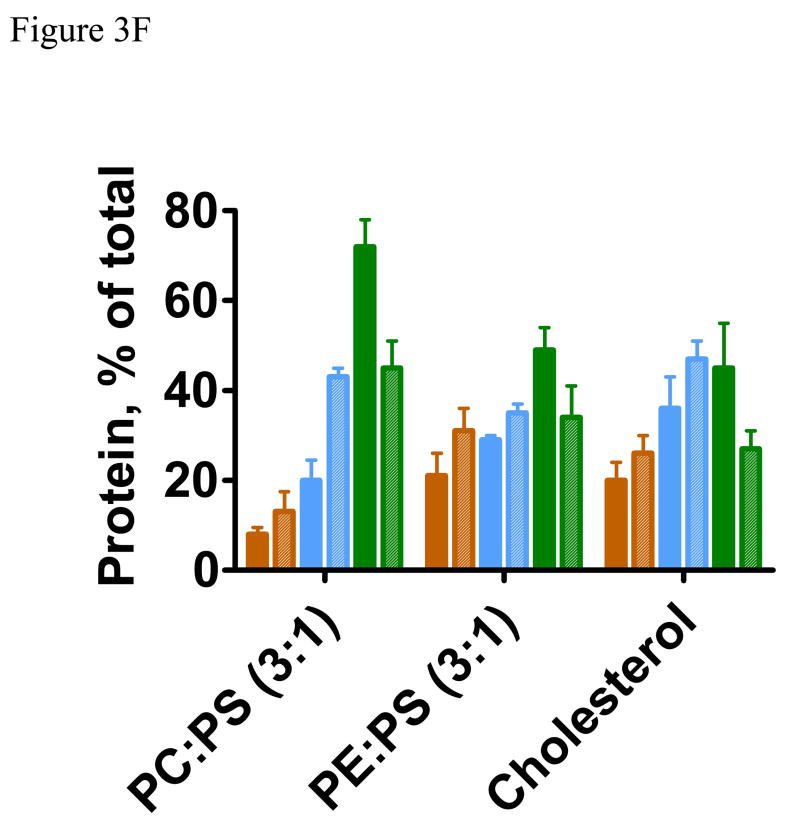

Membrane lipid composition modifies limited proteolysis of annexin A7. A. Trypsin proteolysis of annexin A7 in the absence or presence of 1 mM Ca2+ and in the presence of 20 μM PLV with either C (PC:PS, 3:1) or E (PE:PS, 3:1) composition. Incubations were conducted for 1 (C1 and E1) or 4 h (C4 or E4) at 37° C. B. Ca2+-dependence of annexin A7 proteolysis with trypsin (4 h, 37° C) in presence of 200 μM PLV of C (PC:PS, 3:1) or E (PE:PS, 3:1) composition without or with 1 mM Ca2+ and at annexin A7/trypsin ratio of 40 showed higher levels of annexin A7 in comparison to that in presence of 20 μM PLV (see A above). C. Ca2+ effect on annexin A7 remaining after trypsin proteolysis for 4h in the presence of 200μM PLV and without (●, ◆) or with (○, ◇) 1mM Ca2+. The reaction was conducted using equal amounts of annexin A7 but variable amounts of trypsin. Note that the Ca2+ effect in presence of PC:PS (3:1) PLV was observed at all concentrations of trypsin. D. Limited proteolysis of annexin A7 with trypsin was performed for 4 h in the presence of 0.2 mM PLV of indicated composition and without (filled bar) or with 1 mM Ca2+ (hatched bar). The proteins were quantified after SDS-PAGE and photo imaging against annexin A7 standard. Cholesterol-PLV (PC:PE:PS:cholesterol, 45:20:25:10) contained zero or 5% PIP2 (Cholesterol-PIP2) or DAG (Cholesterol-DAG) with concomitant reduction in PC and PE to 42.5 and 17.5%, respectively. Note that annexin A7 protection against trypsin was mostly by blocking formation of 33 kDa peptide. The presence of DAG, but not PIP2, provides further protection against tryspin. Annexin A7, 47 kDa (

); Peptide 33kDa (

); Peptide 33kDa (

): Peptide 28kDa (

): Peptide 28kDa (

). Results are mean ± SE of 3–5 experiments. E. Limited proteolysis of annexin A7 with chymotrypsin (4 h, 37° C) in presence of 0.2 mM PLV with compositions described in A above and in the absence or presence of 1 mM Ca2+. Major proteolysis products at 37 and 33 kDa are indicated by – in the right margin relative to the position of annexin A7 (47 kDa): F. Comparison of PLV with different compositions showed smaller effects of Ca2+ with no preference for any of the three compositions evaluated. Annexin A7 (

). Results are mean ± SE of 3–5 experiments. E. Limited proteolysis of annexin A7 with chymotrypsin (4 h, 37° C) in presence of 0.2 mM PLV with compositions described in A above and in the absence or presence of 1 mM Ca2+. Major proteolysis products at 37 and 33 kDa are indicated by – in the right margin relative to the position of annexin A7 (47 kDa): F. Comparison of PLV with different compositions showed smaller effects of Ca2+ with no preference for any of the three compositions evaluated. Annexin A7 (

), Peptide 37 kDa (

), Peptide 37 kDa (

) and Peptide 33 kDa (

) and Peptide 33 kDa (

). The proteolysis was performed without (filled bars) or with 1 mM Ca2+ (hatched bars). Results are mean ± SE of three experiments.

). The proteolysis was performed without (filled bars) or with 1 mM Ca2+ (hatched bars). Results are mean ± SE of three experiments.

The chymotrypsin proteolysis generated two major peptides of 37 and 30 kDa in presence of PC:PS (3:1) or PE:PS (3:1) PLV. At 20 μM PLV, the proteolysis in presence of Ca2+ was greater (not shown). At higher PLV concentrations, however, the degradation in presence of Ca2+ was lower (Fig. 3E). Better protection was observed in presence of PE:PS (3:1) in comparison to the PC:PS (3:1) PLV. The degradation was similar in presence of 0.2 mM of either PLV and in the absence or presence of Ca2+ at varying ratios of annexin A7/enzyme (not shown). None of the three different PLVs that were evaluated for these studies showed significant differences in the proteolysis products (Fig. 3F). The major effect of PLV was on degradation of the 30 kDa peptide, which was found to increase in presence of Ca2+. To determine the possible trypsin and chymotrypsin sites, we obtained the N-terminal sequence for the major peptides at 33 and 28 kDa from trypsin and 37 and 30 kDa from chymotrypsin proteolysis (Table 1). Since the N-terminal sequence for trypsin generated peptides matched the N-terminal sequence of recombinant annexin A7, we conclude that the two potential trypsin sites are present in the COOH-terminus. The sequences of chymotrypsin generated peptides were compared with the potential site sequences according to the PeptideCutter program (ExPASY Proteomics Server, Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Geneva, Switzerland). Such comparison indicated that the potential sites were at Y110 and F160 for the 37 kDa and the 33 kDa peptides, respectively, both of which are in the NH2-terminus of annexin A7 [22].

Table 1.

N-terminal sequence of major peptides obtained after limited proteolysis of annexin A7 with trypsin or chymotrypsin.

| Trypsin | Chymotrypsin | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | N-terminal Sequence | Site | N-terminal Sequence | |||

| Peptide 1 | U | G S ? Y P | (33 kDa) | Y110 | – G – P A | (37 kDa) |

| Peptide 2 | U | G S ? Y P | (28 kDa) | F160 | D A – R D | (33 kDa) |

The proteolysis products were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes and stained with Coomassie blue. The relevant bands were excised and processed for N-terminal sequencing. The N-terminal sequence of recombinant annexin A7 was verified to be GSSYP. The potential sequences were GSSYP for both trypsin generated and GGGPA and DAMRD for the chymotrypsin generated 37 and 33 kDa peptides, respectively. U – unknown, but possibly in the COOH-terminus. The undetermined sequence is indicated by ? and – indicates a non-matching residue.

Membrane Binding and Fusion Studies with Lamellar bodies

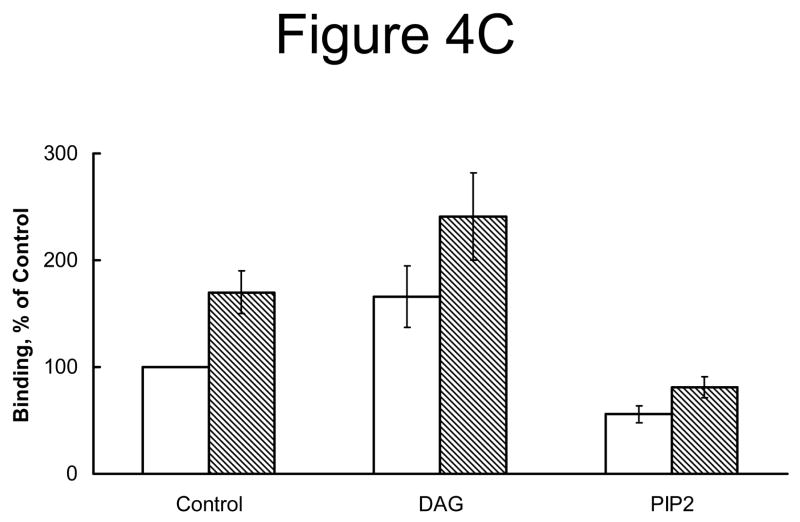

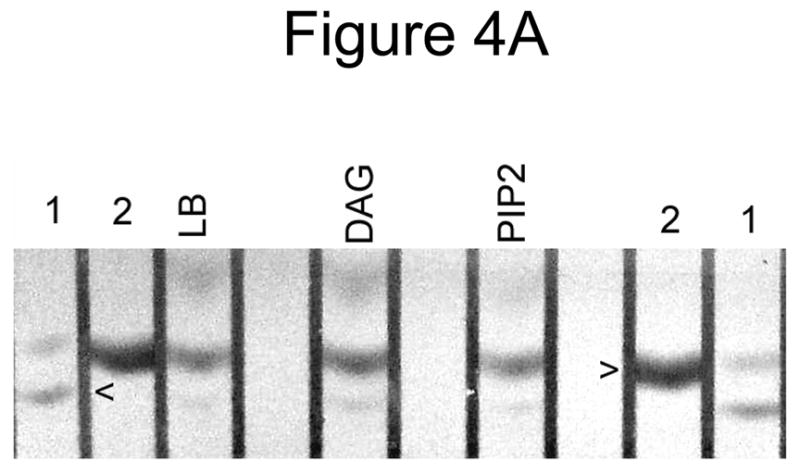

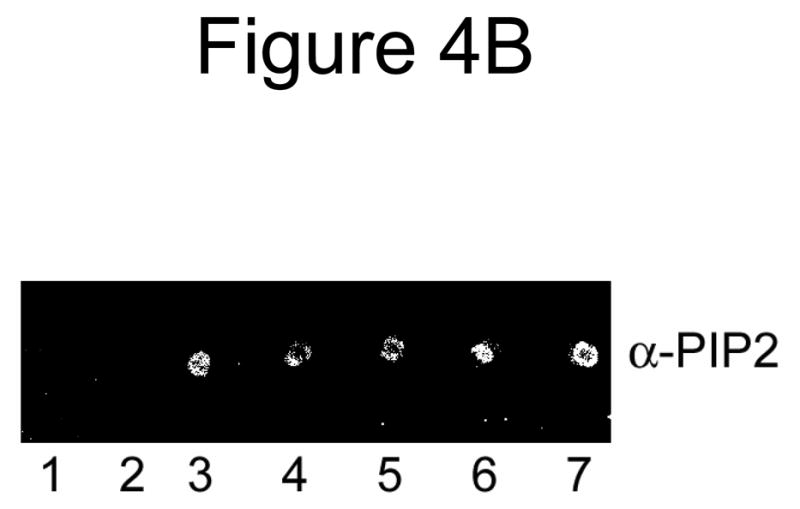

Because the presence of PIP2 or DAG in PLV affected protein fluorescence of annexin A7, we investigated if lamellar body enrichment with PIP2 or DAG would affect binding and membrane fusion activities of annexin A7. In initial studies, we investigated membrane binding activity using PIP2 or DAG containing PLV. Co-sedimentation analysis showed that the Ca2+-independent protein binding was higher for DAG-PLV in comparison to that for PIP2-PLV (not shown). The Ca2+-dependent membrane association of protein was similar for Cholesterol-PLV without or with DAG, but lower for PIP2-PLV. Next, we evaluated protein binding to lamellar bodies that were pre-incubated without or with DAG or PIP2. Such treatment caused lamellar body enrichment with either lipid as confirmed by TLC analysis for DAG and visualization after exposure to I2, or by dot blot analysis for PIP2 with a commercially available antibody (Fig. 4A and B). Annexin A7 binding was higher for lamellar bodies that were incubated with DAG, but not for those incubated with PIP2 (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Annexin A7 binding to lamellar bodies is augmented with increased diacylglycerol content. Incubation of lamellar bodies with DAG or PIP2 increased the respective lipid content of lamellar bodies. A. Lamellar bodies (LB) were incubated at room temperature for 30 min with 60 μM DAG or PIP2 and 10 μM Ca2+. The LB were separated by centrifugation, washed, and their lipids analyzed for DAG by TLC. Authentic standards (arrowheads) for DAG (1) and cholesterol (2) were co-chromatographed. B. Dot blot analysis of lamellar bodies incubated with DAG or PIP2. Lamellar bodies were incubated without (3) or with 1mM PLV containing 5% DAG (4) or PIP2 (5), or with 0.2 mM suspension of DAG (6) or PIP2 (7). Equal aliquots were spotted for dot blot analysis. Controls with buffer (1) or BSA (2) did not show any reactivity. PLV composition was PC:PE:PS:Cholesterol (42.5,17.5:25:10 and 5% DAG or PIP2). C. Annexin A7 binding to DAG and PIP2-enriched lamellar bodies. Isolated lung lamellar bodies were incubated for 10 min without or with 60 μM DAG or PIP2, separated by centrifugation, washed, and evaluated for binding of annexin A7 in the absence (open bar) or presence (hatched bar) of 10 μM Ca2+. Results are expressed relative to binding in the absence of Ca2+ and are mean ± SE of 3–5 experiments. The presence of Ca2+ increased protein binding in all cases. In comparison to others, the DAG-enriched lamellar bodies showed higher annexin A7 binding without or with Ca2+.

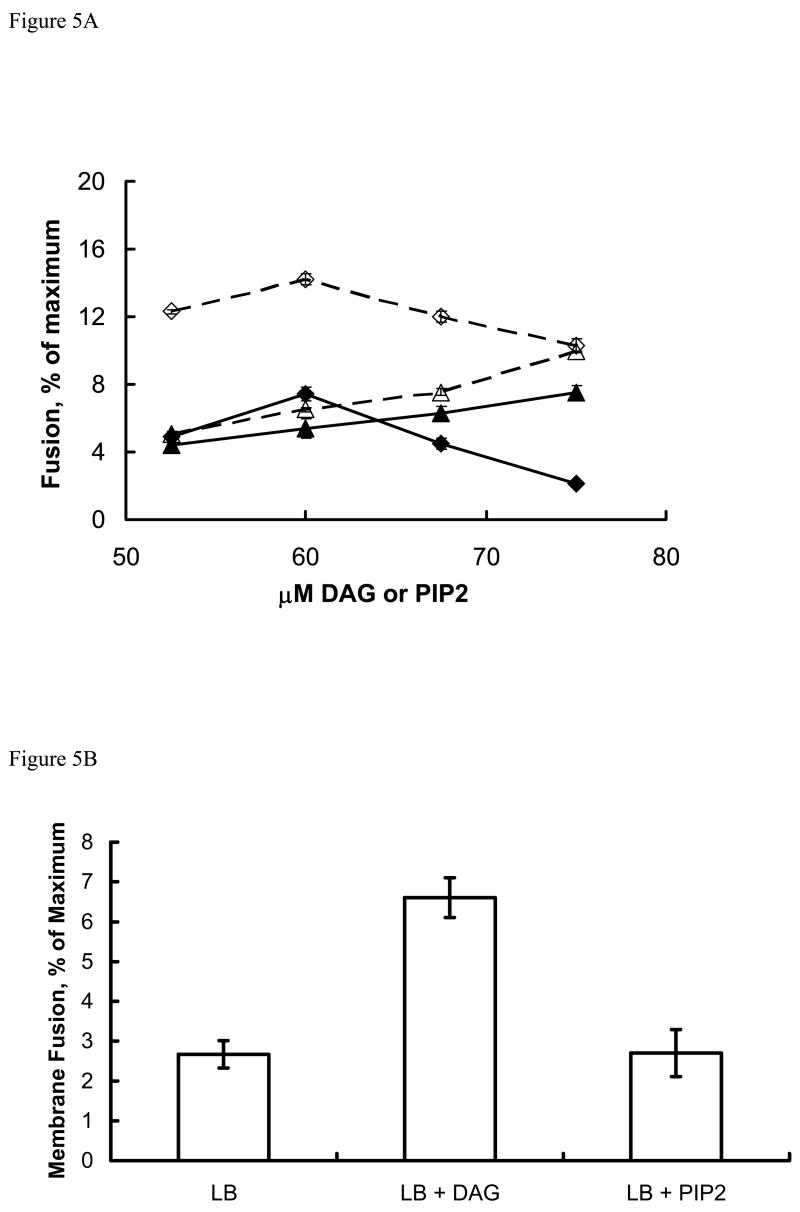

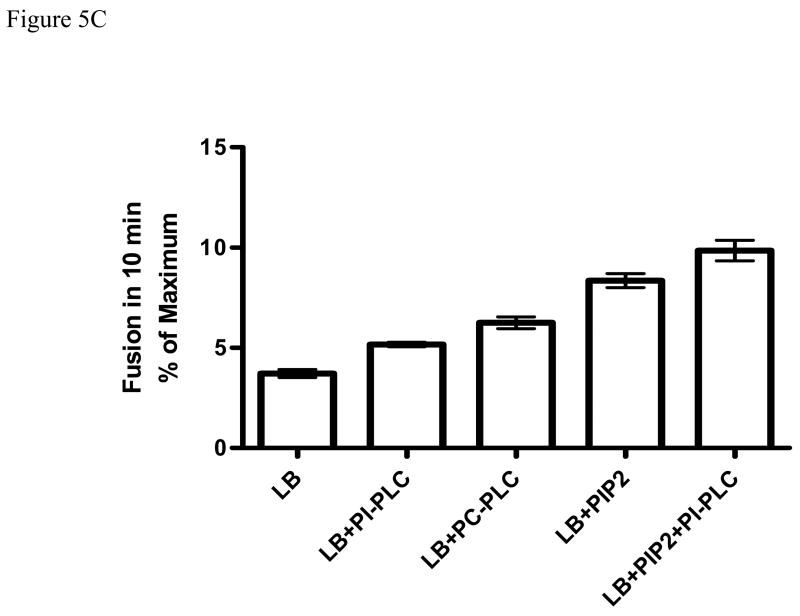

Initial studies with PLV containing various amounts of DAG or PIP2 and 2 μM labeled PLV (the fluorescence probe) showed that the membrane fusion activity of annexin A7 increased with increasing DAG concentration reaching a maximum at 60 μM DAG and then declined at higher concentrations (Fig. 5A). In comparison, the membrane fusion activity of annexin A7 increased with increasing concentration of PIP2. In some experiments, lamellar bodies were added along with DAG (or PIP2) and the Ca2+-dependent fusion activity was assayed. In this mixed assay system, the fusion activity of annexin A7 was higher in the presence than in the absence of lamellar bodies. Increased fusion in presence of lamellar bodies and DAG is likely because of rapid incorporation of DAG in lamellar bodies. In some experiments, as discussed above for the protein binding studies, the lamellar bodies were incubated with PIP2 or DAG and separated by centrifugation before evaluation for the membrane fusion activity of annexin A7. The Ca2+-dependent membrane fusion activity was also higher with DAG-enriched lamellar bodies in comparison to those not enriched (control) or enriched with PIP2 (Fig. 5B). However, the membrane fusion activity of annexin A7 was augmented if the lamellar bodies were pre-incubated with high concentration of PIP2 (0.2 mM). In another series of experiments, we incubated lamellar bodies without or with 0.2 mM PIP2 and treated them with PC-PLC or PI-PLC before evaluation for annexin A7-mediated membrane fusion. The commercial preparations of these enzymes were first evaluated for the formation of DAG in PLV containing zero or 5% PIP2 without or with 10 μM Ca2+. The PI-PLC formed DAG with PIP2-PLV but not with Cholesterol-PLV suggesting that it was specific for PIP2. We did not observe any additional effect of Ca2+ on DAG formation. Treatment of lamellar bodies with either PLC increased the membrane fusion activity of annexin A7 (Fig. 5C). Although the membrane fusion activity was higher with PIP2- enriched lamellar bodies, their treatment with PI-PLC further increased the fusion activity of annexin A7. Thus, several protocols for increasing DAG content of lamellar bodies increased the membrane fusion activity of annexin A7.

Figure 5.

Annexin A7 mediated membrane fusion was measured by lipid mixing technique by measuring change in the transfer efficiency of resonance energy. All assay mixtures contained 10 μg/ml annexin A7 and 2 μM of labeled PLV containing NBD-PE and Rh-PEand suspension of indicated concentrations of DAG, PIP2, or lamellar bodies (20 μg/ml). The fusion reaction was initiated with 10 μM Ca2+. Fusion is expressed as fluorescence increase during 10 min as percent of maximum increase with 1% Triton X-100. A. Concentration-dependent effects of DAG (◆ , ◇) or PIP2 (▲ , Δ) in the absence (closed symbols) or presence (open symbols) of lamellar bodies. The assay mixture contained a fixed concentration of labeled PLV. The presence of lamellar bodies caused consistently greater fusion at each concentration of DAG suggesting rapid incorporation of DAG into lamellar bodies, which enhanced the membrane fusion activity. Mean ± SE of 3–4 reactions. In case of 75 μM PIP2 + lamellar bodies, the fusion was measured only once. B. Lamellar body fusion with PLV following incubation with DAG or PIP2 (60 μM). The membrane fusion was enhanced with lamellar bodies preincubated with DAG. Mean ± SE of 3–4 experiments in each case. C. Lamellar bodies were pre-incubated for 30 min without or with 0.2 mM PIP2 and 10 μM Ca2+, pelleted by centrifugation, washed twice with buffer containing 10 μM Ca2+ and treated for 10 min without or with 1 unit/ml of PI-PLC or PC-PLC. Thus treated lamellar bodies were washed twice and evaluated for membrane fusion with annexin A7 and 10 μM Ca2+. Results are mean ± SE of three separate observations. PLC pretreatment increased membrane fusion in each case.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have presented evidence for a novel role for DAG in annexin A7-mediated fusion of lamellar bodies that is postulated to occur during surfactant secretion. Although a role for DAG and other lipids in signal transduction has long been recognized [31, 33], it is only during the last decade that a role for phosphoinositides in membrane-associated functions of proteins has been investigated (reviewed in [43]). Some protein motifs show high affinity and specificity towards inositol lipids [44, 45]. Several investigators over the last few years have postulated that specific regions of membranes containing cholesterol [46] or phosphoinositide molecules [28, 30] could be preferred sites for interactions with certain proteins that facilitate or participate in the membrane fusion process. Annexin A2 [27–29] and synaptotagmin [47] show affinity towards membranes containing PIP2, which forms microdomains in syntaxin clusters in the membranes [48]. Since phosphoinositide turnover is rapid and involves phosphorylation of inositol phosphatides and degradation through phospholipase and phosphohydrolase enzymes [43], it raises the question of a role for DAG in membrane binding and membrane-associated functions of a protein. In many cell types including type II cells, DAG levels increase following cell stimulation with agents that stimulate PI-PLC and cause hydrolysis of PIP2 [31]. Our current study shows that DAG in membranes increases annexin A7 binding and activity and supports the concept of membrane lipids modifying protein (annexin A7) interaction and function. Such interaction between DAG and protein could alter the molecular organization of the protein with important consequence for the protein function. In type II cells, purinergic and other agents increase cell DAG levels and surfactant secretion. Thus, the DAG regulation of annexin A7 function could have physiological relevance during fusion of lamellar bodies (with plasma membrane) for increasing surfactant secretion.

The Ca2+-dependent membrane binding characteristics have led to several postulated functions for annexin proteins [20]. These proteins demonstrate selectivity in binding to membranes [25, 26, 46, 49, 50], suggesting that the differences in lipid composition of intracellular membranes could contribute to the site-specific actions of these proteins. Since the tryptophan residue (W239) in annexin A7 is present in the second homologous repeat in the core domain of the molecule, changes in protein tryptophan fluorescence [51, 52] would be indicative of molecular reorganization involving this repeat and the various amino acid residues in close vicinity of the tryptophan residue (embedded or surface-exposed). A large change in protein fluorescence with substitution of PC with PE (Fig. 1B), as major phospholipid, suggests change in protein conformation and in the mode of annexin A7 interaction with membranes. In our studies, the increase in protein fluorescence in presence of Cholesterol-PLV (with lipid composition closer to biological membranes) was similar to that seen with PC:PS (3:1). However, inclusion of low levels of signaling lipids, PIP2 or DAG, caused large increases in protein fluorescence (Fig. 1C and 2B and C) suggesting that these lipids could have a role in regulating the protein function by affecting the annexin A7 molecule. Previously, interaction between annexin and Ca2+ was postulated to alter the conformation of the protein core domain in order to explain annexin interactions with membranes [53]. We now propose that interaction with specific membrane lipids would cause further change in the protein molecule and accessibility of specific protein domains for relevant protein functions. Since Ca2+ is required to affect these changes, such reorganization of annexin A7 molecule probably occurs upon cell stimulation.

Given the large variety of physiological functions assigned to annexin proteins and the Ca2+-dependence of protein binding to membranes, several studies employing atomic force microscopy and electron microscopy techniques have showed that, at least in the binary lipid mixture containing PLV, annexin A2 and A5, assemble as 2-dimensional structures along the membrane without penetrating the membranes [54–57]. Our studies demonstrating DPE quenching of tryptophan fluorescence, however, suggest that tryptophan-containing domain of annexin A7 can penetrate into membranes of appropriate lipid composition. Similar conclusion can be drawn from smaller increase in protein fluorescence with DPE-PLV (39%, Fig. 2D) in comparison to that with cholesterol-PLV (97%, Fig. 2A). Although our protocol differed from that used for synaptotagmin [30], annexin A7 appears to interact with trans membranes and penetrate DPE-containing membranes provided the cis membranes contained DAG. Thus, activation of PLC-mediated hydrolysis of PIP2 and formation of DAG would cause further reorganization of annexin A7 bound or in close vicinity of membrane and its penetration into the membrane. Possibly such change in molecular organization facilitates the membrane binding and fusion activity of annexin A7 in vivo.

The proteolysis studies also suggest that lipid composition of membranes could affect protein molecule and, consequently, the accessibility of protease sites. Previous studies have suggested that stable or transient interaction with Ca2+ could expose unique protein domains for the protein function [53, 58, 59]. Annexin proteins show high affinity binding to PS (reviewed in [17]) and have specific PS binding sequences in their core domains [21]. One previous study investigated PS interaction with annexin A4 and A6 by measuring protein effects on the surface pressure of PS monolayer and by evaluating PS protection against proteolysis [60]. The authors suggested that electrostatic interaction between PS and Ca2+-annexin complex could alter the conformation of annexin core domain. However, protein immobilization at surface could also contribute to the inhibition of proteolysis. Thus, additional factors could modify the protein conformation, although partial membrane penetration of protein(s) could still be one underlying cause of protection against proteolysis. Our study demonstrates that other lipids, in addition to PS, also modulate molecular characteristics of protein, which in some cases, results in partial membrane penetration, possibly to facilitate annexin A7 function. However, we cannot exclude that these effects of other lipids (including DAG) require PS, which was present in all PLV, in light of several studies suggesting that annexin proteins do not exhibit significant binding to lipids like PE or PC (reviewed in [17]). Further, since the DAG effect on proteolysis was distinct from PIP2, we postulate that additional molecular organization of annexin A7 occurs following PIP2 hydrolysis to DAG.

Molecular changes during Ca2+-bridging [58] and membrane interactions could promote stable protein binding to membranes as observed with DAG containing membranes including lamellar bodies (Fig. 4C). However, in contrast to higher binding of annexin A2 [28], the binding of annexin A7 to PIP2 containing membranes was lower (Fig. 5) suggesting different modes of membrane interaction of these two annexin proteins that are postulated to promote membrane fusion during lamellar body exocytosis. Certain proteins can bind to PIP2 through well-defined motifs like the plextrin homology domain [43], while other proteins like annexin A2 and actin binding proteins (gelsolin, vilin and MARCKS proteins) could bind through a motif containing cationic residues [28]. Given the high degree of homology in the core domain of annexin proteins, it is likely that the unique NH2-termini of these proteins contribute to this difference in binding to PIP2-membranes. Although PIP2 increases membrane-protein interactions as suggested by a large increase in fluorescence (Figs. 1 and 2), it decreased annexin A7 binding to membranes (Fig. 4C). The underlying cause for the decreased binding is unclear, but we speculate that PIP2 enrichment causes a change in the mode of protein binding to membranes, membrane insertion or electrostatic binding, as previously suggested for annexin A5 [61] and annexin A2 [62] to explain pH effect on protein-membrane interaction. Nevertheless, lamellar bodies appear to bind more annexin A7 than required for membrane fusion, since decreased binding (Fig. 4C) did not reflect in decreased membrane fusion (Fig. 5B). Thus, only a part of the bound annexin A7 may be involved in membrane fusion. The membrane fusion activity of annexin A7 was higher for DAG-enriched PLV or lamellar bodies suggesting that annexin A7 activity may be primarily regulated by DAG. The biphasic effects of DAG concentration, increased fusion at low and decreased fusion at high concentrations, are possibly due to membrane destabilization with high concentrations of DAG [63] or due to alterations in membrane characteristics necessary for supporting fusion. On the other hand, membrane fusion increased with PIP2 concentration and also in lamellar bodies that were preincubated with 0.2 mM PIP2, which possibly increases the PIP2 content of lamellar bodies to sufficiently high levels.

In intact cells, the facilitating effects of DAG on annexin A7-mediated membrane fusion are possibly mediated through multiple mechanisms because of DAG activation of PKC, which causes increased secretion of lung surfactant [34, 35, 37, 64]. Annexin A7 binding to lamellar bodies or plasma membrane from calcium ionophore- or PMA-treated type II cells – both agents activate PKC – is increased [12]. Annexin A7 can also be phosphorylated with PKC, which is associated with increased membrane fusion activity, and the level of phosphorylated annexin A7 correlates well with increased secretion in chromaffin cells [11]. Because of the new evidence supporting a membrane fusion modifying role for DAG, we speculate that by forming annexin A7-binding domains within fusing membranes and modifying the conformation of the bound protein, which may be amenable to PKC-mediated phosphorylation, DAG contributes to promoting annexin A7-mediated membrane fusion during secretion in some cell types.

In conclusion, our studies demonstrate that the annexin A7 interactions with membranes are regulated by lipids other than PS, notably PIP2 and DAG that undergo changes upon cell stimulation. The regulation of annexin A7 activity is a novel function for DAG that occurs at the level of the protein-membrane interaction and affects the binding and membrane fusion activities of this protein. The postulated role for DAG fits well in the overall scheme of surfactant secretion in alveolar type II cells, which upon stimulation with several agents show increased DAG formation (concomitant with PIP2 and PC hydrolysis) and increased secretion.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by grant HL 49959 from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DPE

dansyl phosphatidylethanolamine

- F345

fluorescence at 345 nm

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate

- PI

phosphatidylinositol

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- PKC

protein kinase C

- TAE

Tris-acetate-EGTA

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rooney S, Young SL, Mendelson CR. Molecular and cellular processing of lung surfactant. FASEB Journal. 1993;8:957–967. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.12.8088461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.VanGolde L, Batenburg JJ, Robertson B. The pulmonary surfactant system: biochemical aspects and functional significance. Physiological Reviews. 1988;68:374–455. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1988.68.2.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mason RJ. Biology of alveolar type II cells. Respirology (Carlton, Vic) 2006;11(Suppl):S12–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chander A, Fisher AB. Regulation of lung surfactant secretion. The American journal of physiology. 1990;258:L241–253. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1990.258.6.L241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dietl P, Haller T. Exocytosis of lung surfactant: from the secretory vesicle to the air-liquid interface. Annual review of physiology. 2005;67:595–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.102553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kliewer M, Fram EK, Brody AR, Young SL. Secretion of surfactant by rat alveolar type II cells: morphometric analysis and three-dimensional reconstruction. Experimental lung research. 1985;9:351–361. doi: 10.3109/01902148509057533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mair N, Haller T, Dietl P. Exocytosis in alveolar type II cells revealed by cell capacitance and fluorescence measurements. The American journal of physiology. 1999;276:L376–382. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.2.L376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chander A, Sen N, Spitzer AR. Synexin and GTP increase surfactant secretion in permeabilized alveolar type II cells. American journal of physiology. 2001;280:L991–998. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.5.L991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chander A, Wu RD. In vitro fusion of lung lamellar bodies and plasma membrane is augmented by lung synexin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1086:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(91)90003-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu L, Wang M, Fisher AB, Zimmerman UJ. Involvement of annexin II in exocytosis of lamellar bodies from alveolar epithelial type II cells. The American journal of physiology. 1996;270:L668–676. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.4.L668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caohuy H, Pollard HB. Activation of annexin 7 by protein kinase C in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12813–12821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chander A, Sen N, Naidu DG, Spitzer AR. Calcium ionophore and phorbol ester increase membrane binding of annexin a7 in alveolar type II cells. Cell calcium. 2003;33:11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(02)00177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stahelin RV, Rafter JD, Das S, Cho W. The molecular basis of differential subcellular localization of C2 domains of protein kinase C-alpha and group IVa cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12452–12460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi T, Beuchat MH, Lindsay M, Frias S, Palmiter RD, Sakuraba H, Parton RG, Gruenberg J. Late endosomal membranes rich in lysobisphosphatidic acid regulate cholesterol transport. Nature cell biology. 1999;1:113–118. doi: 10.1038/10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi T, Stang E, Fang KS, de Moerloose P, Parton RG, Gruenberg J. A lipid associated with the antiphospholipid syndrome regulates endosome structure and function. Nature. 1998;392:193–197. doi: 10.1038/32440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmid SL, Cullis PR. Membrane sorting. Endosome marker is fat not fiction. Nature. 1998;392:135–136. doi: 10.1038/32309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raynal P, Pollard HB. Annexins: the problem of assessing the biological role for a gene family of multifunctional calcium- and phospholipid-binding proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1197:63–93. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(94)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerke V, Moss SE. Annexins: from structure to function. Physiological reviews. 2002;82:331–371. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerke V, Creutz CE, Moss SE. Annexins: linking Ca2+ signalling to membrane dynamics. Nature reviews. 2005;6:449–461. doi: 10.1038/nrm1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Creutz CE. The annexins and exocytosis. Science (New York, NY) 1992;258:924–931. doi: 10.1126/science.1439804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montaville P, Neumann JM, Russo-Marie F, Ochsenbein F, Sanson A. A new consensus sequence for phosphatidylserine recognition by annexins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24684–24693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109595200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naidu DG, Raha A, Chen XL, Spitzer AR, Chander A. Partial truncation of the NH2-terminus affects physical characteristics and membrane binding, aggregation, and fusion properties of annexin A7. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1734:152–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chander A, Naidu DG, Chen XL. A ten-residue domain (Y11-A20) in the NH2-terminus modulates membrane association of annexin A7. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:775–784. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clemen CS, Herr C, Lie AA, Noegel AA, Schroder R. Annexin VII: an astroglial protein exhibiting a Ca2+-dependent subcellular distribution. Neuroreport. 2001;12:1139–1144. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200105080-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sen N, Spitzer AR, Chander A. Calcium-dependence of synexin binding may determine aggregation and fusion of lamellar bodies. The Biochemical journal. 1997;322(Pt 1):103–109. doi: 10.1042/bj3220103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creutz CE, Pazoles CJ, Pollard HB. Self-association of synexin in the presence of calcium. Correlation with synexin-induced membrane fusion and examination of the structure of synexin aggregates. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:553–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rescher U, Ruhe D, Ludwig C, Zobiack N, Gerke V. Annexin 2 is a phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate binding protein recruited to actin assembly sites at cellular membranes. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3473–3480. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gokhale NA, Abraham A, Digman MA, Gratton E, Cho W. Phosphoinositide specificity of and mechanism of lipid domain formation by annexin A2-p11 heterotetramer. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42831–42840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508129200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayes MJ, Merrifield CJ, Shao D, Ayala-Sanmartin J, Schorey CD, Levine TP, Proust J, Curran J, Bailly M, Moss SE. Annexin 2 binding to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate on endocytic vesicles is regulated by the stress response pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14157–14164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313025200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bai J, Earles CA, Lewis JL, Chapman ER. Membrane-embedded synaptotagmin penetrates cis or trans target membranes and clusters via a novel mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25427–25435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M906729199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol as second messengers. The Biochemical journal. 1984;220:345–360. doi: 10.1042/bj2200345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balla T. Phosphoinositide-derived messengers in endocrine signaling. The Journal of endocrinology. 2006;188:135–153. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Billah MM, Anthes JC. The regulation and cellular functions of phosphatidylcholine hydrolysis. The Biochemical journal. 1990;269:281–291. doi: 10.1042/bj2690281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griese M, Gobran LI, Rooney SA. ATP-stimulated inositol phospholipid metabolism and surfactant secretion in rat type II pneumocytes. The American journal of physiology. 1991;260:L586–593. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1991.260.6.L586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sen N, Chander A. Alkalosis- and ATP-induced increases in the diacyglycerol pool in alveolar type II cells are derived from phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylinositol. The Biochemical journal. 1994;298(Pt 3):681–687. doi: 10.1042/bj2980681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sen N, Grunstein MM, Chander A. Stimulation of lung surfactant secretion by endothelin-1 from rat alveolar type II cells. The American journal of physiology. 1994;266:L255–262. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.3.L255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warburton D, Buckley S, Cosico L. P1 and P2 purinergic receptor signal transduction in rat type II pneumocytes. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66:901–905. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.2.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chander A, Dodia CR, Gil J, Fisher AB. Isolation of lamellar bodies from rat granular pneumocytes in primary culture. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;753:119–129. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(83)90105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chander A, Johnson RG, Reicherter J, Fisher AB. Lung lamellar bodies maintain an acidic internal pH. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:6126–6131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Canadian journal of biochemistry and physiology. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bers DM. A simple method for the accurate determination of free [Ca] in Ca-EGTA solutions. The American journal of physiology. 1982;242:C404–408. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1982.242.5.C404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical biochemistry. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balla T. Inositol-lipid binding motifs: signal integrators through protein-lipid and protein-protein interactions. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2093–2104. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DiNitto JP, Cronin TC, Lambright DG. Membrane recognition and targeting by lipid-binding domains. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:re16. doi: 10.1126/stke.2132003re16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lemmon MA. Phosphoinositide recognition domains. Traffic (Copenhagen, Denmark) 2003;4:201–213. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2004.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lang T, Bruns D, Wenzel D, Riedel D, Holroyd P, Thiele C, Jahn R. SNAREs are concentrated in cholesterol-dependent clusters that define docking and fusion sites for exocytosis. Embo J. 2001;20:2202–2213. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bai J, Tucker WC, Chapman ER. PIP2 increases the speed of response of synaptotagmin and steers its membrane-penetration activity toward the plasma membrane. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:36–44. doi: 10.1038/nsmb709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aoyagi K, Sugaya T, Umeda M, Yamamoto S, Terakawa S, Takahashi M. The activation of exocytotic sites by the formation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate microdomains at syntaxin clusters. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17346–17352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jost M, Zeuschner D, Seemann J, Weber K, Gerke V. Identification and characterization of a novel type of annexin-membrane interaction: Ca2+ is not required for the association of annexin II with early endosomes. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 2):221–228. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Konig J, Gerke V. Modes of annexin-membrane interactions analyzed by employing chimeric annexin proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1498:174–180. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ladokhin AS, Jayasinghe S, White SH. How to measure and analyze tryptophan fluorescence in membranes properly, and why bother? Analytical biochemistry. 2000;285:235–245. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ladokhin AS. Fluorescence Spectroscopy in Peptide and Protein Analysis. In: Meyers RA, editor. Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; Chichester: 2000. pp. 5762–5779. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sobota A, Bandorowicz J, Jezierski A, Sikorski AF. The effect of annexin IV and VI on the fluidity of phosphatidylserine/phosphatidylcholine bilayers studied with the use of 5-deoxylstearate spin label. FEBS Lett. 1993;315:178–182. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81158-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Menke M, Ross M, Gerke V, Steinem C. The molecular arrangement of membrane-bound annexin A2-S100A10 tetramer as revealed by scanning force microscopy. Chembiochem. 2004;5:1003–1006. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oling F, Santos JS, Govorukhina N, Mazeres-Dubut C, Bergsma-Schutter W, Oostergetel G, Keegstra W, Lambert O, Lewit-Bentley A, Brisson A. Structure of membrane-bound annexin A5 trimers: a hybrid cryo-EM - X-ray crystallography study. J Mol Biol. 2000;304:561–573. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reviakine II, Bergsma-Schutter W, Brisson A. Growth of Protein 2-D Crystals on Supported Planar Lipid Bilayers Imaged in Situ by AFM. J Struct Biol. 1998;121:356–361. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.4003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voges D, Berendes R, Burger A, Demange P, Baumeister W, Huber R. Three-dimensional structure of membrane-bound annexin V. A correlative electron microscopy-X-ray crystallography study. J Mol Biol. 1994;238:199–213. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swairjo MA, Concha NO, Kaetzel MA, Dedman JR, Seaton BA. Ca(2+)-bridging mechanism and phospholipid head group recognition in the membrane-binding protein annexin V. Nature structural biology. 1995;2:968–974. doi: 10.1038/nsb1195-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liemann S, Lewit-Bentley A. Annexins: a novel family of calcium- and membrane-binding proteins in search of a function. Structure. 1995;3:233–237. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bandorowicz–Pikula J, Sikorski AF, Bialkowska K, Sobota A. Interaction of annexins IV and VI with phosphatidylserine in the presence of Ca2+: monolayer and proteolytic study. Mol Membr Biol. 1996;13:241–250. doi: 10.3109/09687689609160602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Isas JM, Cartailler JP, Sokolov Y, Patel DR, Langen R, Luecke H, Hall JE, Haigler HT. Annexins V and XII insert into bilayers at mildly acidic pH and form ion channels. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3015–3022. doi: 10.1021/bi9922401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lambert O, Cavusoglu N, Gallay J, Vincent M, Rigaud JL, Henry JP, Ayala-Sanmartin J. Novel organization and properties of annexin 2-membrane complexes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10872–10882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313657200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barona T, Byrne RD, Pettitt TR, Wakelam MJ, Larijani B, Poccia DL. Diacylglycerol induces fusion of nuclear envelope membrane precursor vesicles. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41171–41177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412863200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chander A, Sen N, Wu AM, Spitzer AR. Protein kinase C in ATP regulation of lung surfactant secretion in type II cells. The American journal of physiology. 1995;268:L108–116. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.1.L108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]