Introduction

Primary pancreatic lymphoma is a rare nonepithelial tumor of the pancreas that can mimic pancreatic adenocarcinoma clinically and radiographically. Differentiating between the 2 malignancies is important because pancreatic lymphoma has a high cure rate. We report a case of primary pancreatic lymphoma presenting as a pancreatic mass.

Case Report

A 55-year-old man with a medical history significant for coronary artery disease and obstructive sleep apnea presented to the hospital with a 3-month history of abdominal pain and recent onset of bright red blood per rectum. Approximately 3 months before admission, the patient reported the onset of waxing and waning abdominal pain of increasing severity, which migrated from the right lower to right upper quadrant. Occasionally the pain occurred in the epigastrium and radiated to the back. He reported poor appetite, early satiety, and a 20-pound weight loss over the previous 2 months. He had had nausea, dry heaves, night sweats, and fatigue.

One day before admission, the patient noted 2 loose bowel movements that turned the toilet water brownish-red. He has not had any bowel movements since this time. He denied prior hematochezia or melena, but had had small amounts of bright red blood on the toilet paper thought to be related to hemorrhoids. On physical examination, the patient had normal blood pressure and pulse rate; his abdomen was obese, soft, and nondistended. He had mild tenderness in the epigastric region with no peritoneal signs. His stool was guaiac positive. Laboratory analysis revealed a hematocrit drop from 42 % to 27 % over the past 3 months. The white blood cell count was within normal limits and lactate dehydrogenase was elevated to 2 times the normal level. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a 7 × 5-cm well-defined mass encasing the celiac axis and involving the head of the pancreas. Multiple enlarged lymph nodes were present adjacent to the mass (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The CT scan demonstrates a lobulated 7 x 5-cm mass centered in the region of the pancreatic head and celiac axis.

Upper endoscopy revealed an ulcerated friable mass in the second portion of the duodenum with no active bleeding (Figures 2, 3). Endoscopic ultrasound examination revealed an approximately 4-cm well-defined hypoechoic homogeneous mass in the head of the pancreas (Figures 4, 5); with adjacent 2-cm well-defined hypoechoic lymph nodes (Figure 6).

Figure 2.

Endoscopic view of an ulcerated mass in the second portion of the duodenum.

Figure 3.

Another view of the ulcerated mass in the second portion of the duodenum.

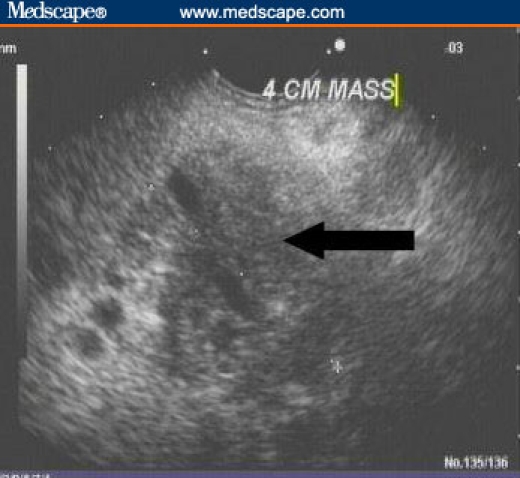

Figure 4.

Endoscopic ultrasound image of a 4 x 5-cm hypoechoic homogeneous mass (solid arrow) in the head of the pancreas.

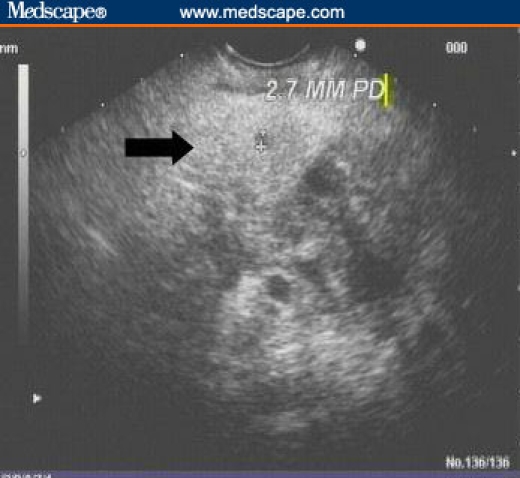

Figure 5.

Endoscopic ultrasound image demonstrating normal pancreatic parenchyma (solid arrow) adjacent to the hypoechoic mass. The pancreatic duct is 2.7 mm in diameter.

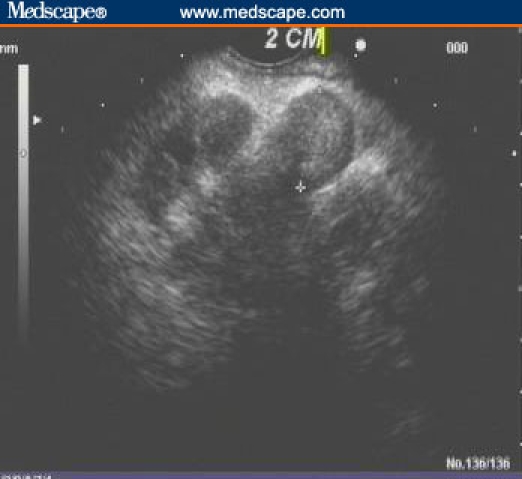

Figure 6.

Endoscopic ultrasound image of a 2-cm well-defined hypoechoic lymph node adjacent to the pancreas.

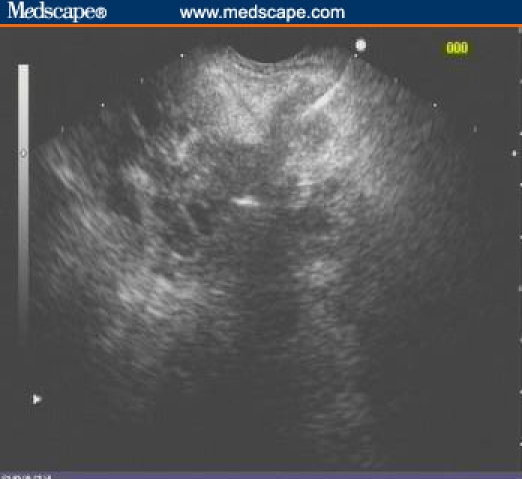

Fine-needle aspiration of the mass and the lymph node (Figure 7) was performed. Pathology demonstrated the presence of malignant lymphoma dominated by large cells; flow cytometry confirmed the presence of large B-cell lymphoma. The patient was treated with 4 cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) with complete resolution of the pancreatic mass.

Figure 7.

Endoscopic ultrasound image demonstrating fine-needle aspiration of a hypoechoic lymph node.

Discussion

Pancreatic lymphoma is categorized as a nonepithelial tumor of the pancreas. Although rare, these tumors need to be considered in the differential diagnosis of a pancreatic mass. As described by Behrns and colleagues[1] in 1994, certain criteria must be met to suggest that the lymphoma is of pancreatic origin and not a nodal lymphoma extending to the pancreas. According to these criteria, a lymphoma localized to the pancreas is defined as a pancreatic mass with involvement of peripancreatic lymph nodes without distal lymph node involvement, no hepatic or splenic metastases, and a normal white blood cell count.[1]

Pancreatic lymphoma represents less than 1% to 2% of all pancreatic malignancies, and less than 1% of all extranodal nonHodgkin's lymphomas.[2,3] The symptoms may be nonspecific, but can include abdominal pain, weight loss, night sweats, and small bowel obstruction. The hallmark laboratory finding is an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level. An elevated carbohydrate antigen 19-9 level may be misleading for the diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma because it has also been shown to be increased in patients with pancreatic lymphoma. Cross-sectional imaging may be helpful in differentiating between the 2 conditions; however, it is not specific. Histologic analysis is crucial for differentiating between adenocarcinoma and lymphoma of the pancreas. As in our case, endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration has replaced more invasive approaches to obtain tissue for histology and flow cytometry.[4,5] In some cases, laparotomy may be required for definitive diagnosis.[6] Treatment options include surgical resection, chemotherapy alone, or combined radiation and chemotherapy.[7] Response rates to chemotherapy alone are very good, with approximately 72% of patients showing no evidence of disease at 34 months.[8]

Footnotes

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at dforcione@partners.org or to Paul Blumenthal, MD, Deputy Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication via email: pblumen@stanford.edu

Contributor Information

Michael Piesman, Brigham & Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

David G. Forcione, Gastroenterology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital; Instructor in Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts Author's email: dforcione@partners.org.

David L. Carr-Locke, The Endoscopy Institute, Brigham & Women's Hospital; Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

References

- 1.Behrns KE, Sarr MG, Strickler JG. Pancreatic lymphoma: is it a surgical disease. Pancreas. 1994;9:662–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ. Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer. 1972;29:252–260. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197201)29:1<252::aid-cncr2820290138>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nayer H, Weir EG, Sheth S, Ali SZ. Primary pancreatic lymphomas: a cytopathologic analysis of a rare malignancy. Cancer. 2004;102:315–321. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jhala NC, Jhala D, Eltoum I, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy: a powerful tool to obtain samples from small lesions. Cancer. 2004;102:239–246. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arcidiacono PG, Carrara S. Endoscopic ultrasonography: impact in diagnosis, staging and management of pancreatic tumors. An overview. JOP. 2004;5:247–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koniaris LG, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, et al. Is there a role for surgical resection in the treatment of early-stage pancreatic lymphoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:319–330. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grimison PS, Chin MT, Harrison ML, Goldstein D. Primary pancreatic lymphoma–pancreatic tumours that are potentially curable without resection, a retrospective review of four cases. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller TP, et al. Chemotherapy alone compared with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy for localized intermediate- and high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:21–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807023390104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]