Case Presentation

A 13-year-old boy is referred to Johns Hopkins Hospital Pediatric Emergency Room (ER) with episodes of “legs giving out” for 1 week.

Immediate History

The patient is a 13-year-old boy with history of occipital headache who, while practicing relaxation techniques for his pain, developed an episode of generalized weakness. At its onset, he reported a generalized painful sensation and within a few seconds became weak and unable to move his arms or legs. The entire episode lasted a few minutes. He experienced no loss of consciousness and was speaking coherently. During the event, he felt anxious and his breathing appeared to be labored, with shortness of breath, although he was not hyperventilating. His heart felt like it was racing, but his family noted no change in skin color, and the patient felt no dizziness, tingling, nausea, or vomiting; he had no incontinence. After a few minutes, the tachycardia resolved and the patient began to move his limbs.

He was taken immediately to a local ER where his exam was unremarkable. A basic metabolic panel and creatine kinase (CK) were normal, and he was discharged home with follow-up to his primary care physician.

Over the ensuing week he continued to experience frequent brief episodes of generalized weakness and he was referred to the Johns Hopkins Hospital Pediatric ER.

Headache History

The patient's occipital headaches began following minor head trauma; he hit the back of his head after crouching down to pick up an object under his desk at school. He experienced no loss of consciousness, ecchymosis, edema, or headache at the time. Two days later he woke with a dull, throbbing, occipital headache that he rated 7 out of 10 on the pain scale. He had no associated nausea, vomiting, photophobia, or phonophobia, but he described allodynia triggered by brushing his hair and flexing his neck. The headache did not worsen with standing or sitting. Because of his persistent pain, he was evaluated at an outside ER where a basic metabolic panel, complete blood cell count, and head CT were normal. Subsequent MRI of the cervical spine and Lyme antibody titers were negative, and he was referred to a pain clinic.

Other History

Past medical history

Normal birth. Hospitalized for a femur fracture as a toddler.

Family history

Mother reports a history of ocular migraines. She also has a history of Graves disease for which she underwent iodine ablation, medical treatment, and partial thyroidectomy. A maternal aunt takes medication for migraines. The patient's younger sister also has headaches thought to be migraines.

Social history

The patient is in the seventh grade earning “B's and C's.” Parents are separated.

Medications

During the weeks before his evaluation at Johns Hopkins Hospital, he received ibuprofen, acetaminophen with codeine, methylprednisolone 1-week pack, and diclofenac with little change in his headache pain.

Pediatric ER Exam and Clinical Course

In the Pediatric ER, his exam was notable for orthostatic hypotension (lying down pulse 60, blood pressure 113/68; sitting pulse 73, blood pressure 125/79; standing pulse 95, blood pressure 99/70) and a moderate occipital headache with allodynia.

His funduscopic exam and motor testing (including reflexes) were normal. Previous imaging was reviewed and felt to be within normal limits. He was encouraged to increase fluid intake and was sent home with a trial of amitriptyline and sumatriptan with telephone follow-up. Medications did not bring relief and episodes of weakness increased to several times a day.

At this time, the differential diagnosis by possible anatomic location for this patient's episodes of headache and generalized weakness is as follows.

Brain: migraine variant possible but no acute exacerbation in headache pain associated with events; Arnold-Chiari malformation (not seen on sagittal MRI); spontaneous intracranial hypotension (headache not postural); tumor; pituitary adenoma; seizures

Spine: high cervical-spine lesion may account for occipital headache and weakness (C-spine MRI normal); weakness episodes with full recovery not typical for vascular compromise such as a spinal arteriovenous malformation (AVM); other less likely entities include Guillain-Barré syndrome; transverse myelitis; mass lesion

Peripheral nerve/neuromuscular junction: periodic paralysis; myasthenia gravis (no bulbar symptoms; recovers too quickly from weakness)

Metabolic: anemia, orthostatic hypotension

Psychogenic: conversion disorder, malingering

Clinical Course

Two days later, the patient returned to the Johns Hopkins Pediatric ER in a wheelchair during his longest episode of weakness, having lasted more than 2 hours upon presentation.

The previous evening for dinner he ate a plate of pasta. On the day of presentation, he awoke normally but experienced 1–2 brief episodes of weakness while still in bed. He then arose from bed without difficulty and ate a granola bar. After sitting on the couch to play with his PlayStation, he felt dizzy and crumpled to the floor, unable to move his extremities but able to move his head. He was conscious throughout the episode and denied palpitations, diaphoresis, vertigo, or change in sensation.

On arrival in the ER approximately 2 hours after onset, vital signs revealed a pulse of 113 beats per minute and BP 129/86. Motor examination confirmed that the patient was indeed unable to move his limbs to painful stimulation. Sensory examination showed intact light touch, cold, pinprick, vibration, and proprioception. His reflexes were present but diminished.

-

1.What is the leading diagnosis on the differential?

-

Recalling the previous differential diagnoses and normal imaging studies, a spinal cord lesion or brain pathology is unlikely in light of the patient's normal mental status and sensory exam with nonlateralizing motor findings. The clinical history of recurrent bouts of weakness with this episode of prolonged paralysis is strongly suggestive of periodic paralysis.

-

Recalling the previous differential diagnoses and normal imaging studies, a spinal cord lesion or brain pathology is unlikely in light of the patient's normal mental status and sensory exam with nonlateralizing motor findings. The clinical history of recurrent bouts of weakness with this episode of prolonged paralysis is strongly suggestive of periodic paralysis.

-

Recalling the previous differential diagnoses and normal imaging studies, a spinal cord lesion or brain pathology is unlikely in light of the patient's normal mental status and sensory exam with nonlateralizing motor findings. The clinical history of recurrent bouts of weakness with this episode of prolonged paralysis is strongly suggestive of periodic paralysis.

-

Recalling the previous differential diagnoses and normal imaging studies, a spinal cord lesion or brain pathology is unlikely in light of the patient's normal mental status and sensory exam with nonlateralizing motor findings. The clinical history of recurrent bouts of weakness with this episode of prolonged paralysis is strongly suggestive of periodic paralysis.

-

Pertinent History Relating to Diagnosis

The patient and his family are unaware of any history of hemiplegic migraine, periodic paralysis, or seizures. Further questions can be asked based on an understanding of the etiologies of periodic paralysis, which can be categorized into familial and acquired forms (Table).

Table.

Etiology of Periodic Paralysis

| Inherited Periodic Paralysis | Acquired Periodic Paralysis |

|---|---|

Chloride channel disorders

|

Secondary hyperkalemic periodic paralysis may be seen in association with:

|

Sodium channel disorders

|

Secondary hypokalemic periodic paralysis may be seen in association with:

|

| Andersen syndrome | |

| Schwartz-Jampel syndrome | |

| Hypokalemic periodic paralysis, types 1 and 2 |

The patient has no known channelopathies, unusual syndromes, or comorbid medical conditions to support your suspicion of periodic paralysis.

-

2.Which of the following studies should you order?

-

Thyroid function tests, stat potassium, CK, and EKG should be ordered.

-

Thyroid function tests, stat potassium, CK, and EKG should be ordered.

-

Thyroid function tests, stat potassium, CK, and EKG should be ordered.

-

Thyroid function tests, stat potassium, CK, and EKG should be ordered.

-

Thyroid function tests, stat potassium, CK, and EKG should be ordered.

-

Thyroid function tests, stat potassium, CK, and EKG should be ordered.

-

Thyroid function tests, stat potassium, CK, and EKG should be ordered.

-

Lab Results

The patient's potassium level, drawn approximately 2 hours after onset of paralysis, is 3.4 (lower limit of normal is 3.5). A 12-lead EKG is normal. CK is 162, within normal limits.

After roughly 4 hours of paralysis, the patient began moving his limbs and was discharged home from the ER after full recovery to baseline. Amitriptyline was discontinued because it was thought to possibly worsen orthostasis, and divalproex sodium was started for persistent headache pain.

The next day, thyroid studies drawn the previous day in the ER showed: Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH): < 0.02 (normal 0.5–4.5)<br/>Free T4: 1.3 (normal 0.7–1.6)

Consultation with an endocrinologist resulted in scheduling a clinic visit for the patient. However, when we contacted the patient, his mother reported that he was having frequent episodes of weakness. Because of a concern about his worsening symptoms and rare reports of arrhythmias with hypokalemic periodic paralysis, we admitted the patient for expedient work-up and monitoring.

-

3.What are some clues in the ER that can be used to distinguish sporadic periodic paralysis from thyrotoxic periodic paralysis?

-

Increased heart rate and elevated blood pressure were found to be significantly different in a case series defining thyrotoxic periodic paralysis and sporadic periodic paralysis (patients with normal thyroid functions).[1] These investigators suggested that other lab values, such as potassium, phosphate, CK, and liver function tests, were not helpful in distinguishing sporadic from thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. This patient had an elevated heart rate of 113 beats per minute during his prolonged episode.

-

Increased heart rate and elevated blood pressure were found to be significantly different in a case series defining thyrotoxic periodic paralysis and sporadic periodic paralysis (patients with normal thyroid functions).[1] These investigators suggested that other lab values, such as potassium, phosphate, CK, and liver function tests, were not helpful in distinguishing sporadic from thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. This patient had an elevated heart rate of 113 beats per minute during his prolonged episode.

-

Increased heart rate and elevated blood pressure were found to be significantly different in a case series defining thyrotoxic periodic paralysis and sporadic periodic paralysis (patients with normal thyroid functions).[1] These investigators suggested that other lab values, such as potassium, phosphate, CK, and liver function tests, were not helpful in distinguishing sporadic from thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. This patient had an elevated heart rate of 113 beats per minute during his prolonged episode.

-

Increased heart rate and elevated blood pressure were found to be significantly different in a case series defining thyrotoxic periodic paralysis and sporadic periodic paralysis (patients with normal thyroid functions).[1] These investigators suggested that other lab values, such as potassium, phosphate, CK, and liver function tests, were not helpful in distinguishing sporadic from thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. This patient had an elevated heart rate of 113 beats per minute during his prolonged episode.

-

Hospital Course and Evaluations

After admission to the hospital, the patient experienced no further episodes of paralysis and he had returned to baseline with good muscle strength. We detected no arrhythmias and the monitor was discontinued. According to his mother, this was the longest symptom-free period encompassing the preceding week; she noted, however, that he was not eating as well while he was hospitalized.

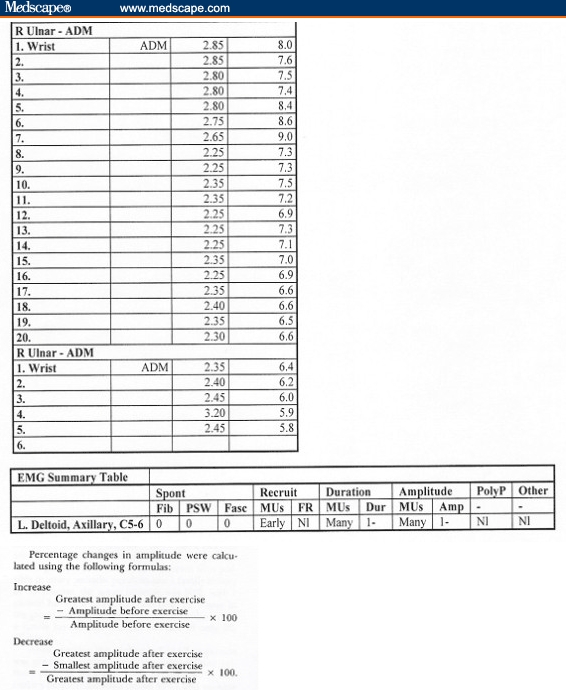

To substantiate the diagnosis of periodic paralysis, we ordered electrodiagnostic testing (EMG) with nerve conduction studies (NCS), including measurements post exercise (the McManis test), which confirmed the diagnosis.

We included post-exercise testing as part of the EMG/NCS because of its ability to differentiate definite periodic paralysis, based on a study by McManis and colleagues.[2] In this study, a series of patients with clinically definite and possible periodic paralysis underwent EMG recording. Patients with definite primary periodic paralysis had a mean increase in compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitude of 35% immediately post exercise and a mean decline of 40% measured over 20+ minutes post exercise. In the control group, the mean increase was only 11% with only 15% decrease after exercise.

A reduction in CMAP of greater than 40% with slow return to baseline was seen only in primary and secondary periodic paralysis and paramyotonia congenita, making it a useful test for confirming suspicion of these disorders, but not one that could distinguish the mechanism or type of periodic paralysis.

Our patient's EMG (Figure) includes calculations showing the post-exercise decrement. Only 20 minutes of exercise was performed but results clearly suggested an abnormal gradual decrement in the amplitudes.

Figure.

EMG demonstrates abnormal decrement in amplitudes.

Additional thyroid tests showed:

Repeat TSH: <0.02

Free T3: 522 (335–480); Free T4: 1.6 (0.7–1.6)

T3: 1.72 (0.8–2.0); T4: 8.8 (4.5–11.5)

Thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins 142 (< 125)

Anti-thyroglobin Ab negative

Anti-microsomal Ab negative

Final Diagnosis

The final diagnosis for this patient was hyperthyroid periodic paralysis.

This diagnosis is typically associated with hypokalemia in the acute phase. Our patient had borderline low serum potassium of 3.4 obtained 2 hours after onset of paralysis. We assume that it was lower in the acute phase. Fortunately, cardiac monitoring uncovered no abnormalities and his potassium did not require replacement. Because the patient experienced no episodes during his admission when potassium levels could be measured, electrodiagnostic testing and thyroid function studies confirmed the diagnosis.

We discharged the patient with a prescription for propranolol 60 mg daily. We advised him to avoid high-carbohydrate meals and excessive exercise because they may precipitate episodes.

The patient later underwent a 24-hour iodine-123 uptake thyroid scan which showed an uptake of 46.1% (normal 12%–35%). Radioactive iodine (I-131) thyroid ablation was performed and he has been symptom-free with no further episodes of weakness or headache.

Discussion

Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis is observed about 10 times more commonly in adult Asian men than in whites. Our patient is unusual not only because he is not Asian but because his age makes him perhaps the youngest patient in the literature with thyroid-related periodic paralysis.

The pathophysiology of periodic paralysis remains somewhat controversial. There is evidence that an abnormal hyperinsulinemic response to carbohydrate loading may be responsible for triggering a cascade of events that results in increased stimulation of the Na-K-ATPase pump.[3] This then leads to an intracellular shift of potassium causing hypokalemia, refractory hyperpolarization, and ultimately paralysis.[4] Furthermore, catecholamines have also been shown to increase the activity of the Na-K-ATPase pump, which may explain why nonspecific beta-blockers such as propranolol can help abort attacks.

Treatment of a prolonged episode with potassium is controversial because of the risk for rebound hyperkalemia. Intravenous propranolol 3–4 mg/kg has been used to abort prolonged episodes.[4] There is some risk for arrhythmia with hypokalemia. Recommendations for laboratory studies during an acute paralysis attack include a emergent measurements of potassium, phosphate, CK, urine potassium, urine creatinine, and consideration of cardiac monitoring.

The etiology of our patient's headache could be related to his diagnosis. At least 3 theoretical connections between headache and thyrotoxic periodic paralysis are possible. First, some studies suggest an association between hyperthyroidism and headache. A case series of 30 patients with chronic headaches who underwent thyroid function tests showed that 6 of the 30 were hyperthyroid.[5] Also of interest, treatment for thyrotoxic periodic paralysis is propranolol, which is used in migraine prophylaxis. Second, both disorders share some type of channelopathy as a genetic mutation.[4] Third, the purported role of a hyperinsulinemic response in periodic paralysis invokes the possibility of an autoimmune role similar to what is seen in thyroid disease.

Footnotes

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at asakonj1@jhmi.edu or to Paul Blumenthal, MD, Deputy Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication via email: pblumen@stanford.edu

Contributor Information

Ai Sakonju, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland Author's email: asakonj1@jhmi.edu.

Jennifer Huffman, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

Harvey Singer, Department of Pediatric Neurology, the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

References

- 1.Lin YF, Wu CC, Pei D, Chu SJ, Lin SH. Diagnosing thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:339–342. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(03)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McManis PG, Lambert EH, Daube JR. The exercise test in periodic paralysis. Muscle Nerve. 1986;9:704–710. doi: 10.1002/mus.880090805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shishiba Y, Shimizu T, Saito T, Shizume K. Elevated immunoreactive insulin concentration during spontaneous attacks in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. Metabolism. 1972;21:285–290. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(72)90071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kung A. Clinical review: Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis: a diagnostic challenge. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2490–2495. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwasaki Y, Kinoshita M, Ikeda K, Takamiya K, Shiojima T. Thyroid function in patients with chronic headache. Int J Neurosci. 1991;57:263–267. doi: 10.3109/00207459109150700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]