Case Presentation

A 61-year-old man was referred for evaluation because of iron-deficiency anemia.

Six months ago, he developed pain, swelling, and stiffness of both hands and the right knee. His symptoms did not improve with analgesics or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Three months ago, he was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. He began methotrexate and had dramatic improvement in joint symptoms. One month later, he was diagnosed with iron-deficiency anemia. He was begun on oral iron supplementation and recently was referred for gastrointestinal evaluation.

The review of systems was negative for fever, night sweats, or weight loss. There was no dysphagia, dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia. There was no alteration in frequency or consistency of bowel movements.

The patient works in a funeral home performing various tasks, including embalming. He does not smoke, use illegal drugs, or drink excessive amounts of alcohol. His father has hypertension, and his mother has rheumatoid arthritis.

There was no other history of serious medical illness, hospitalizations, or surgery. Medications included methotrexate 15 mg taken orally every week, famotidine 20 mg daily, and ferrous gluconate 300 mg twice daily. The famotidine had been prescribed by the referring physician for unclear reasons.

The physical examination showed normal vital signs. The patient weighed 201 lb; body mass index was 28. All systems were examined and found to be normal.

Important laboratory studies at the time of referral revealed the following: hemoglobin, 11.7 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume, 75; white blood cell count, 9,900 cells/mcL; and platelets, 248,000 cells/mcL. Electrolytes and routine serum chemistries were normal. Serum iron was 38 mcg/dL; total iron-binding capacity was 307 mcg/dL; ferritin was 8 mcg/dL; antinuclear antibody was negative; thyroid-stimulating hormone level was 0.6 mU/L; antithyroglobulin antibody was <20 IU/mL; and serum gastrin level was 399 pcg/mL. He was positive for anti-Helicobacter pylori antibodies and negative for antiparietal cell antibodies.

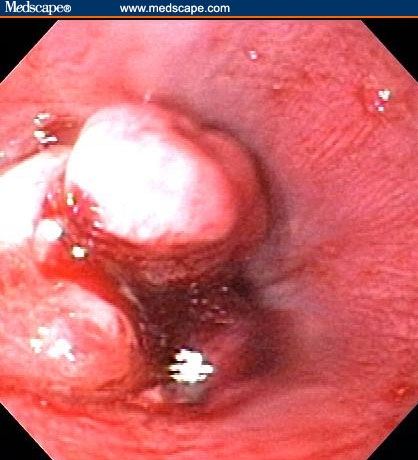

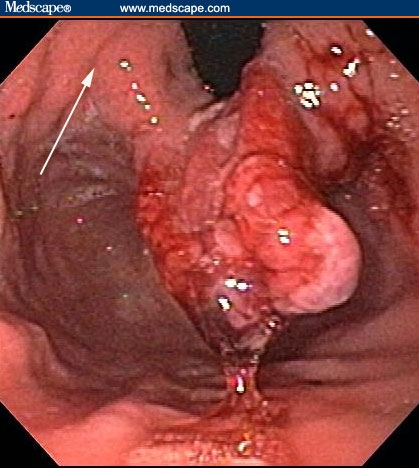

The patient had a normal colonoscopy. He also underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. The body of the esophagus was normal but a polypoid mass protruded up from the gastric cardia at the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 1). The retroflexed view from the stomach confirmed that the lesion originated from the gastric side of the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 2). The lesion was 3 cm long and was erythematous, nodular, friable, and oozing blood. Adjacent mucosa (arrow in Figure 2) appeared erythematous, nodular, and irregular. There were at least 6 other polypoid masses originating from the gastric mucosa in both the gastric corpus (Figures 3 to 5) and antrum (Figures 6 and 7). The masses varied in size from 0.5 cm to 3.0 cm, and all were covered with an abnormal mucosa that appeared erythematous and irregular. The gastric mucosa between the lesions did not have the usual smooth uniform texture – it was irregular in contour and inhomogeneous color (Figures 8 and 9). Some of the gastric folds in the corpus appeared thick (Figure 10).

Figure 1.

Mass in distal esophagus.

Figure 2.

The mass in Figure 1 actually originated from the gastric cardia. The arrow points to the adjacent mucosa, which is abnormal-appearing.

Figure 3.

Polyps in the body of the stomach.

Figure 5.

Polyps in the body of the stomach.

Figure 6.

Polyps in the antrum of the stomach.

Figure 7.

Polyps in the antrum of the stomach.

Figure 8.

The entire gastric mucosa was nodular and red.

Figure 9.

The entire gastric mucosa was nodular and red.

Figure 10.

Some of the folds in the body of the stomach were thick.

Diagnostic Question

-

1.

What is a reasonable differential diagnosis for the endoscopic findings shown in Figures 1 through 10?

Assuming that there is a single etiologic process, we should consider diseases that cause both diffuse gastritis or gastropathy and that are associated with focal raised, thickened, or polypoid mucosal lesions. Please click on Next Page for in-depth discussion

Differential Diagnosis

The poor correlation between the endoscopic appearance of gastric mucosa and histologic abnormalities seen on biopsy is readily acknowledged.[1] Gastric mucosa that appears “normal” on endoscopy is associated with impressive and diagnostic histologic abnormalities in approximately one third of cases.[1] Conversely, “abnormal”-appearing gastric mucosa (eg, red, nodular, irregular, thickened, raised) is a nonspecific finding. These endoscopic abnormalities are compatible with many different gastropathies or gastritides and can be associated with normal histology in approximately 25% of cases.[1] For these reasons, many experts advocate taking gastric biopsies in every patient undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.[2,3] In our patient, the focal polypoid lesions combined with the more subtle diffuse gastric mucosal abnormalities strongly suggest that a significant disease is present in the patient's stomach.

Again, assuming that a single disease process is responsible for the findings, we should consider diseases that cause both diffuse gastritis or gastropathy and that are associated with focal raised, thickened, or polypoid mucosal lesions. Several types of diffuse gastritis/gastropathy are worthy of consideration.

1. Chronic H pylori gastritis is the most common type of diffuse gastritis/gastropathy.[4] Although it begins as an antral-predominant gastritis, progression to the body, fundus, and cardia of the stomach over many decades is common and well-described.[5] Over the same time course, there is progression of the depth of the associated histologic abnormalities. In the early stages, the inflammatory process and histologic changes are superficial. The now “famous” H pylori lesion – active chronic gastritis – refers to the polymorphonuclear leukocytes (active) infiltrating the surface epithelial cell layer and the lymphocytes (chronic) infiltrating the lamina propria. These are the diagnostic histologic features of H pylori gastritis, often seen in conjunction with the H pylori organism. However, over time, the inflammation extends to the deep glands and intraglandular area, causing progressive loss of glandular mass (atrophy). Frequently, the surface epithelium undergoes intestinal metaplasia. When H pylori gastritis is associated with large and friable lesions, there is always concern about dysplastic change or frank carcinoma in the intestinal metaplasia. It is widely believed that this sequence of events – progression from active chronic H pylori gastritis to gastric atrophy to intestinal metaplasia to dysplasia to cancer – is the most common pathway of adenocarcinoma development in the stomach. This malignancy is one of the leading causes of cancer death worldwide. However, the presence of 5 or 6 polypoid lesions, some >2 cm, is not compatible with either the usually flat intestinal metaplasia or the usually focal adenocarcinoma.

The host response to H pylori gastritis varies greatly.[4,5] A small subset of infected persons develops a monoclonal proliferation of B lymphocytes in response to H pylori antigen. These patients develop marginal zone-B cell lymphoma in the setting of diffuse active chronic gastritis. Multifocal lesions (ulcerations and masses) are commonly observed in this condition. Although the polypoid lesions seen in this patient do not have the typical appearance of MALT (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) lymphoma, the possibility should at least be considered.

2. The second most common type of diffuse gastritis/gastropathy is reactive gastropathy.[4] There are many synonyms for this condition, including reflux gastritis (because of its universal presence in the gastric mucosa after a Billroth II gastrectomy), chemical gastritis (because of its strong association with NSAID use), and type C gastritis (because it is neither type A [autoimmune] nor type B [H pylori-positive]). Histologic evaluation of reactive gastropathy shows very few inflammatory cells (thus, gastropathy rather than gastritis). The most dramatic histologic change is a corkscrew appearance of the glands in the superficial mucosa; this is called foveolar hyperplasia. The epithelial cells themselves lose intracellular mucous and develop large dark nuclei. The lamina propria can show edema, smooth muscle proliferation, and vascular congestion. The gastric endoscopic findings in a postoperative stomach or in a patient taking NSAIDs often include marked color change, irregularity, and focal raised lesions. Such large polypoid lesions as those seen in our patient would be unusual in the setting of reactive gastropathy alone. However, both H pylori and NSAIDs in a unique host could produce hyperplastic polyps. (See the discussion of hyperplastic polyps below.)

3. All other causes of diffuse gastritis/gastropathy are much less common. Autoimmune gastritis should be suspected when there is chronic gastritis atrophy or intestinal metaplasia predominantly in the gastric body.[4] Autoimmune gastritis is often found in the evaluation of patients with pernicious anemia and in association with antibodies to intrinsic factor and parietal cells. In the past, autoimmune gastritis was considered distinct from H pylori gastritis – it was assumed that the former was purely immunologic and the latter was purely infectious. However, when some patients were found to have both typical autoimmune gastritis and H pylori infection, questions were raised regarding such a dichotomy.[6] There is convincing evidence that some patients have all the features of autoimmune gastritis as a consequence of H pylori infection.[7,8] The best evidence for this is the normalization of serum B12 and hemoglobin concentrations after treatment of H pylori infection.[9] Our patient is obviously prone to autoimmune disease, given his active rheumatoid arthritis and other autoantibodies. He also has hypergastrinemia, suggesting that he has hypochlorhydria. Thus, the diffuse gastric mucosal abnormalities could be due to autoimmune gastritis, regardless of the presence or absence of H pylori.

But what about our patient's focal polypoid lesions? Are they compatible with autoimmune gastritis, reactive gastropathy, or H pylori gastritis? Seventy-five percent of all gastric polyps are hyperplastic polyps.[10] Microscopic examination of these polyps shows variable features, including elongated and dilated surface glands with chronically inflamed lamina propria. Hyperplastic polyps can be associated with any form of longstanding gastric inflammation or injury, including H pylori gastritis, autoimmune gastritis, or reactive gastropathy. Regression of hyperplastic polyps has been associated with eradication of H pylori infection.[11] If any of these forms of gastritis/gastropathy are the gastric mucosal pathologic condition in our patient, the most likely diagnosis of the polypoid lesions would be hyperplastic polyps.

4. Lymphocytic gastritis is another form of diffuse gastritis; it is associated with both H pylori infection and celiac sprue.[12] This form of gastritis can be associated with a variety of endoscopic abnormalities,[4] including some of the abnormalities seen in our patient. In moderate disease, the endoscopic examination shows chronic erosions: raised lesions topped with a small break or depression in the mucosa.[13] This is termed “varioliform gastritis” and strongly resembles the lesion seen in Figure 7. The most severe forms of lymphocytic gastritis have large mucosal folds that resemble those seen in Ménétrièr's disease, both clinically and endoscopically. The large gastric folds are frequently due to foveolar hyperplasia, as in the case of reactive gastropathy or hyperplastic polyps. The diagnosis of lymphocytic gastritis depends on histologic demonstration of large numbers of normal-appearing lymphocytes infiltrating not only the lamina propria, but also the surface and glandular epithelial cells. In most cases, there is an intraepithelial lymphocyte for every 2 to 3 surface and glandular epithelial cells.[4]

5. Crohn's disease is rarely associated with endoscopic abnormalities in the stomach, but histologic abnormalities of the normal-appearing gastric mucosa may occur in approximately 50% of patients.[4,14,15] As in the intestine, Crohn's disease of the stomach is usually a focal or multifocal process. Patients with Crohn's disease in the small bowel or colon may have “focally enhanced gastritis” seen in one area of a low-power microscopic field and normal gastric mucosa in adjacent areas.[14,15] Granulomas are seen in about 10% of Crohn's disease patients with gastric involvement if numerous biopsies are taken.[14,15] Although hyperplastic and inflammatory polyps can occur whenever there is a chronic source of inflammation and injury to the gastric mucosa, the polypoid lesions seen in our patient have not been described in Crohn's disease of the stomach.

6. A last type of diffuse gastritis that should be considered in the differential diagnosis is eosinophilic gastritis. In this disease, an endoscopically abnormal gastric mucosa with erythema, irregularity, or frank ulceration is found on microscopic examination to have abundant eosinophils infiltrating the mucosa. Usually no specific cause is identified. Sometimes it is associated with a systemic autoimmune disease, such as scleroderma or polymyositis.[4] In addition, eosinophilic gastritis may rarely be seen in the setting of an acute illness due to Anisakis larva invading the gastric mucosa.[16] Eosinophilic gastritis may also be related to food allergy.[17] The idiopathic form is usually part of a localized or diffuse eosinophilic gastroenteritis, a steroid-responsive gastrointestinal disease that shares some clinical features with Crohn's disease.[4]

Gastric Histology

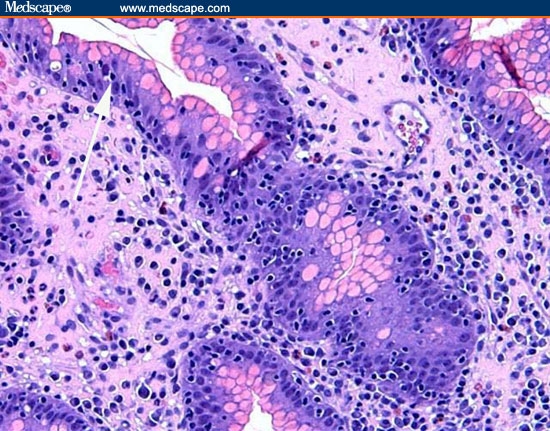

Biopsies were taken of gastric mucosa and the polypoid lesions. Figures 11 through 13 are representative of the gastric mucosa, and Figures 14 and 15 are representative of the polypoid lesions.

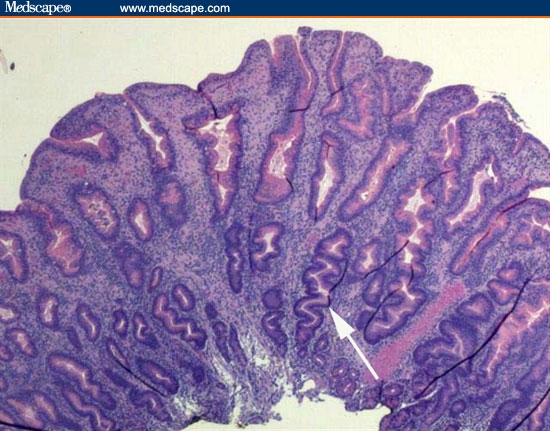

Figure 11.

A low-power view of the gastric body. There is profound separation of the deep gastric glands (atrophy).

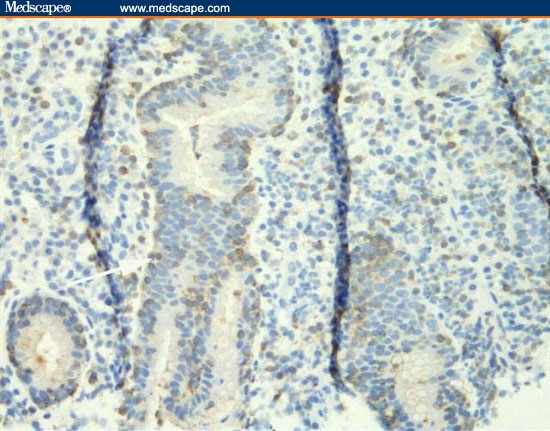

Figure 13.

The biopsy from the gastric body is stained with the T-cell stain CD3. The intraepithelial lymphocytes are staining positive because they are T cells.

Figure 14.

This biopsy is from one of the polyps. It shows foveolar hyperplasia.

Figure 15.

A higher-power view of the polypoid lesion shown in Figure 14 reveals numerous intraepithelial lymphocytes in the polypoid lesion.

Diagnostic Question

-

2.On the basis of the gastric histology seen in Figures 11 through 15 and the previous discussion regarding differential diagnosis, which of the following is your final diagnosis?

- H pylori superficial active chronic gastritis with lamina propria lymphocytes (chronic) and surface epithelium infiltrated with polymorphonuclear leukocytes (active).

- H pylori or autoimmune-induced multifocal atrophic gastritis (inflammation extending to the deep glands of the gastric corpus and intraglandular area, resulting in progressive loss of glandular mass), with intestinal metaplasia (the surface epithelium forms small intestinal villi with goblet cells).

- Reactive gastropathy, with very few inflammatory cells and a corkscrew appearance of the glands in the superficial mucosa (foveolar hyperplasia) in addition to lamina propria edema, smooth muscle proliferation, and vascular congestion.

- Lymphocytic gastritis, with large numbers of normal-appearing lymphocytes infiltrating not only the lamina propria but also the surface and glandular epithelial cells, such that there is a lymphocyte for every 2 to 3 epithelial cells.

- Crohn's disease gastritis, with “focally enhanced gastritis” seen in one area of a low-power microscopic field and normal gastric mucosa seen in adjacent areas as well as occasional granulomas.

-

Eosinophilic gastritis, with abundant eosinophils infiltrating the mucosa.The patient was diagnosed with lymphocytic gastritis. Please click on Next Page for in-depth discussion.

Diagnosis

The correct diagnosis is lymphocytic gastritis. Figure 11 is a low-power view of the gastric body. It shows infiltration of the mucosa with inflammatory cells and the profound separation of the deep gastric glands (atrophy; arrow). Figure 12 is a higher-power view of the same area, showing that the infiltrating cells are normal-appearing, small lymphocytes. The cells are not only present in the lamina propria between the glands, but are infiltrating the epithelial lining cells of the surface epithelium (arrow) and the deeper glands. The number of lymphocytes in the surface and foveolar epithelium per 100 epithelial cell nuclei is greater than 75. The lymphocytes are small and round with no nuclear atypia. The clear halo around the nuclei of some of the lymphocytes (arrow) is a common fixation artifact. Figure 13 shows a similar area of the stomach but is stained with the T-cell stain CD3. The intraepithelial lymphocytes are almost all T cells, as is seen in lymphocytic gastritis. This means that the patient does not have H pylori-related B-cell lymphoma. Figure 14 shows a representative biopsy from one of the polypoid lesions. There is marked corkscrewing of the deep gastric glands (foveolar hyperplasia; white arrow), as has been described in some cases of lymphocytic gastritis and Ménétrièr's disease. However, a higher-power view (Figure 15) shows the prominent lymphocytes typical of lymphocytic gastritis that are not seen in Ménétrièr's disease or reactive gastropathy.

Figure 12.

A higher-power view of the same area seen in Figure 11. Lymphocytes are present between the glands, and numerous lymphocytes are in the surface epithelium and epithelial cells of the deeper glands.

Clinical Course and Outcome

Small bowel biopsies were normal. No H pylori was seen on histology, although serology was positive. Repeated endoscopy (before the patient was started on H pylori therapy) showed improved endoscopic findings and decreased lymphocytic infiltration histologically. Anemia improved with iron supplementation, and the patient was treated for H pylori. The patient continues to have no gastrointestinal symptoms and has a stable hemoglobin level.

Discussion

Lymphocytic gastritis represents a small subset among the numerous gastridities.[4] Its reported frequency in routine practice is 1% to 9% among patients undergoing endoscopy for dyspepsia and 15% to 45% among patients with celiac disease (also known as celiac sprue).[3] Differentiation between lymphocytic gastritis and other chronic gastritides and normal mucosa requires documenting intraepithelial lymphocytes, with the intraepithelial lymphocytes numbering approximately 20 to 30 per 100 epithelial cells.

The cause of lymphocytic gastritis is unknown. The most common disease associations include celiac sprue and H pylori infection. Approximately one third of patients with lymphocytic gastritis have concomitant celiac sprue; approximately 10% to 30% of patients with celiac sprue have lymphocytic gastritis.[12,18,19] It has been suggested that lymphocytic gastritis represents a host response to an intraluminal antigen, either gluten or another.[2] Hayat and colleagues[20] have found similar HLA antigens in both celiac sprue and lymphocytic gastritis.

It is estimated that one third of patients with lymphocytic gastritis have H pylori infection; approximately 4% of H pylori-infected patients have lymphocytic gastritis.[12] Multiple studies have demonstrated that eradication of H pylori infection can reduce lymphocytic infiltration and corpus inflammation and resolve dyspeptic symptoms and anemia.[13,20] The role of H pylori in this setting has been controversial because serologic evidence of infection frequently occurs in the absence of demonstrable identification of the organism by stain or other means.[21] This has led to the speculation that lymphocytic gastritis is an abnormal immune response associated with bacterial clearance.[20,21]

Most cases of lymphocytic gastritis have been described in asymptomatic patients older than 50 years of age. Symptoms that can occur include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss.[13,22,23] Case reports have noted initial presentations of iron-deficiency anemia[13] and gastrointestinal bleeding.[22] Multiple reports have attributed a protein-losing gastroenteropathy to lymphocytic gastritis.[23] Polypoid lesions seen in our case have not previously been associated with any specific symptoms. Bleeding can occur from erosions and ulcerations in gastric mucosa without the dramatic polypoid lesions seen in our case.[22]

The natural history of patients with lymphocytic gastritis is also unclear. Healing after therapy with histamine-2 receptor blockers or proton-pump inhibitors, as well as without any therapy, has been described.[5] The effect of H pylori eradication on severity of histologic abnormalities is also controversial.[20,21]

Although longitudinal studies have not been performed, there may be an association between lymphocytic gastritis and gastric lymphoma and adenocarcinoma. There is an increased prevalence of lymphocytic gastritis in both primary gastric MALT lymphoma and gastric adenocarcinoma.[24] At this time, there are no specific surveillance recommendations for patients with lymphocytic gastritis.

In summary, lymphocytic gastritis is an uncommon form of gastritis that may be an incidental finding at endoscopy or be a cause of hypoalbuminemia, gastrointestinal bleeding, anorexia, or weight loss. The discovery of lymphocytic gastritis should prompt clinical consideration of celiac sprue. Serologic testing for H pylori should also be performed and treatment initiated if results are positive.

Figure 4.

Polyps in the body of the stomach.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: A Man With Rheumatoid Arthritis and Iron-Deficiency Anemia See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at chrisyeh@alumni.rice.edu or to Paul Blumenthal, MD, Deputy Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in MedGenMed via email: pblumen@stanford.edu

Contributor Information

Christine Yeh Hachem, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas Author's email: chrisyeh@alumni.rice.edu.

Hala El-Zimaity, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada.

Richard Goodgame, Department of Medicine, Gastroenterology Section, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas.

References

- 1.Khakoo SI, Lobo AJ, Shepherd NA, Wilkinson SP. Histological assessment of the Sydney classification of endoscopic gastritis. Gut. 1994;35:1172–1175. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.9.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpenter HA, Talley NJ. Gastroscopy is incomplete without biopsy: clinical relevance of distinguishing gastropathy from gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:917–924. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sipponen P, Stolte M. Clinical impact of routine biopsies of the gastric antrum and body. Endoscopy. 1997;29:671–678. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owen DA. Gastritis and carditis. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:324–341. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000062995.72390.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham DY, Genta RM, Dixon MF. Gastritis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varis O, Valle J, Siurala M. Is Helicobacter pylori involved in the pathogenesis of the gastritis characteristic of pernicious anemia? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:705–708. doi: 10.3109/00365529309098277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faller G, Steininger H, Kranziein J, et al. Antigastric autoantibodies in Helicobacter pylori infection: implications of histological and clinical parameters of gastritis. Gut. 1997;41:619–623. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.5.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stopeck A. Links between Helicobacter pylori infection, cobalamin deficiency and pernicious anemia. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1229–1230. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.9.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaptan K, Beyan C, Ural AU, et al. Helicobacter pylori - is it a novel causative agent of vitamin BI2 deficiency? Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1349–1353. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.9.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stolte M, Sticht T, Eidt S, et al. Frequency, location, age and sex distribution of various types of gastric polyps. Endoscopy. 1994;26:659–665. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1009061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohkusa T, Takashimizu I, Fujiki K, et al. Disappearance of hyperplastic polyps in the stomach after eradication of Helicobacter pylori: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:712. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-9-199811010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu TT, Hamilton SR. Lymphocytic gastritis: association with etiology and topology. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:153–158. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199902000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimoyama Y, Mukai M, Asato Y, Ochiai A. Clinical and endoscopic improvement of lymphocytic gastritis with eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:251–254. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.116457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oberhuber G, Puspok A, Oesterroicher C, et al. Focally enhanced gastritis - a frequent type of gastritis in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:698–706. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright CL, Riddell RH. Histology of the stomach and duodenum in Crohn's disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:383–390. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199804000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinkus GS, Coolidge C, Little MD. Intestinal anisakiasis. First case report from North America. Am J Med. 1975;59:114–120. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(75)90328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldman H, Projansky R. Allergic proctitis and gastroenteritis in children. Clinical and mucosal biopsy features in 53 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986;10:75–86. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198602000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feeley KM, Heneghan MA, Stevens FM, McCarthy CF. Lymphocytic gastritis and celiac disease: evidence of a positive association. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:207–210. doi: 10.1136/jcp.51.3.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayat M, Arora DS, Wyatt JI, O'Mahony S, Dixon MF. The pattern of involvement of the gastric mucosa in lymphocytic gastritis is predictive of the presence of duodenal pathology. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:815–819. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.11.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayat M, Arora DS, Dixon MF, Clark B, O'Mahony S. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the natural history of lymphocytic gastritis. Gut. 1999;45:495–498. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.4.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sundaram KK, Mendall MA. Lymphocytic gastritis and Helicobater pylori: reluctant mucosal partners? Helicobacter. 2000;5:248–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss A, Yoshida E, Poulin M, Gascoyne R, Owen D. Massive bleeding from multiple gastric ulcerations in a patient with lymphocytic gastritis and celiac sprue. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:354–357. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199707000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amenomori M, Umemoto T, Kushima R, Hattori T. Spontaneous remission of hypertrophic lymphocytic gastritis associated with hypoproteinemia. Int Med. 1998;37:1019–1022. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.37.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffiths AP, Wyatt J, Jack AS, Dixon MF. Lymphocytic gastritis, gastric adenocarcinoma, and primary gastric lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:1123–1124. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.12.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]