Abstract

A 77-year-old white diabetic woman was brought to our emergency department (ED) after becoming lightheaded and hypotensive at home. Her routine tests including a chest radiograph were normal. Her electrocardiogram (ECG) showed significant ST segment elevation in leads V1 to V4. Serial cardiac enzymes and troponin were within normal limits. Her ECG met the criteria for type 1 Brugada syndrome. Brugada syndrome, which is more common in young Asian males, is an arrhythmogenic disease caused in part by mutations in the cardiac sodium channel gene SCN5A. To diagnose the Brugada syndrome, 1 ECG criterion and 1 clinical criterion should exist. Brugada syndrome can be associated with ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation; the only treatment proven to prevent sudden death is placement of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator, which is recommended in symptomatic patients or in those with ventricular tachycardia induced during electrophysiologic studies and a type 1 ECG pattern of Brugada syndrome. It is important to recognize the Brugada ECG pattern and to differentiate it from other etiologies of ST segment elevation on ECG.

Case Presentation

A 77-year-old white female patient was brought to the ED after becoming hypotensive and feeling lightheaded at home. The paramedics reported smelling natural gas at her home upon their arrival. Her blood pressure was 69/45 mm Hg and her oxygen saturation was 75% on room air. She was given 1 L of normal saline intravenously and 2 L/min O2 by nasal cannula, and her blood pressure and O2 saturation improved to 117/62 mm Hg and 95%, respectively. Her temperature was 97.1 °F, pulse rate 88 beats per minute, and her respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute. She did not have any chest pain or palpitation. Her list of medications included triamterene/hydrochlorothiazide, lisinopril, aspirin, metformin, gemfibrozil, and supplemental vitamins for treatment of her hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and a history of transient ischemic attack. Physical examination was unremarkable for any cardiopulmonary abnormality or any pertinent findings.

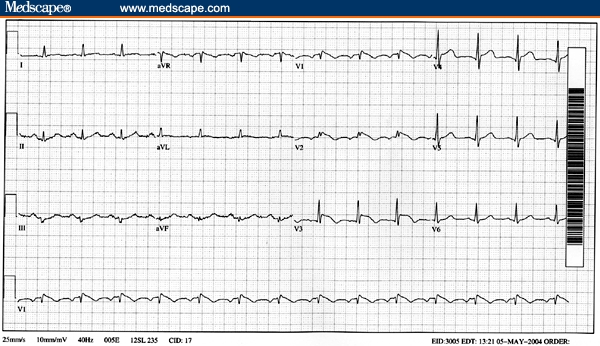

Her electrocardiogram (Fig. 1) showed significant ST segment elevation in leads V1 to V4. Serial cardiac enzymes and troponin were within normal limits. Cardiac catheterization did not show any significant coronary artery stenosis. Her initial ECG met the criteria of type 1 Brugada syndrome and her follow-up ECG became normal.

Figure 1.

The patient's electrocardiogram showed a J point elevation with a downsloping ST segment in V1 to V3, associated T wave inversion, absence of reciprocal ST depression, and pseudo-right bundle branch block pattern, which are typical features of type 1 Brugada pattern.

Brugada Syndrome

Brugada and Brugada first described the eponymous syndrome as a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic presentation with pseudo right bundle branch block (RBBB), ST segment elevation in the right precordial ECG leads and association with sudden cardiac death.[1] It later became clear that widening of the QRS and presence of RBBB are usual but not necessary features of the anomaly.[2] The prevalence and incidence of this syndrome in the United States is not known, but it is common in south Asia and Japan. Brugada syndrome usually presents with syncope and is frequently associated with arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation, supraventricular tachycardia, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT), and ventricular fibrillation (VF). It is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in patients with a structurally normal heart. It is more common in males than females and typically first presents in the third decade of life, although it has been reported in children and the elderly too.

Genetic Factors and Pathogenesis

In about 30% of patients with this syndrome a dominant loss-of-function mutation in the cardiac Na channel gene, SCN5A, has been detected.[3] A gain-of-function mutation in the same gene can lead to a congenital form of long QT syndrome.[4] The sodium channelopathy leaves the outward potassium current unopposed, resulting in losing of the action potential dome in the involved parts of right ventricular epicardium. This creates a voltage gradient between the involved and intact areas, which appears as J-waves and ST segment elevation on 12-lead surface ECG. In addition to this transmural dispersion, there is a voltage gradient between the involved and intact areas of the epicardium, which results in dispersion of the repolarization and can give rise to premature beats by a phase 2 reentry mechanism and may also induce VT and VF.[5] Amplification of the intrinsic electrical heterogeneities among the 3 principal ventricular cell types with sodium channel blockers (eg, procainamide), calcium channel blockers (eg, verapamil), K+ channel openers (eg, pinacidil), and metabolic and ischemic conditions may cause J point elevation through the same mechanism or may unmask the Brugada syndrome. The Brugada syndrome becomes unmasked in association with beta blockers, tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressant use, vagotonic agents, cocaine, and alcohol intoxication and in a febrile state.[5,6] There is no evidence in the literature that hypotension or hypoxemia (present in this patient) could unmask the Brugada ECG pattern.

Despite the autosomal transmission, the syndrome is 8 to 10 times more common in males than females, and this is attributed to intrinsic differences in the ventricular action potentials between the sexes.[7] Recent studies suggest that testosterone may have a role in this syndrome, and 2 cases have been reported that showed disappearance of Brugada-type ECG findings after surgical castration.[8]

Diagnostic Criteria

Up to 3 ECG variants of Brugada syndrome have been described, but the main one, type 1, is associated with ST segment elevation in right precordial leads. It usually is a J point elevation with a downsloping ST segment, and the ST elevation usually tapers off going toward leads V4 to V6. Additional features that can help to differentiate it from other causes of ST elevation are: associated T wave inversion, absence of reciprocal ST depression, pseudo RBBB pattern, and normal QTc. Type 2 has a saddleback appearance with a high take-off ST-segment elevation of ≥ 2 mm followed by a trough displaying ≥ 1 mm ST elevation followed by either a positive or a biphasic T-wave. Type 3 has either a saddleback or a coved appearance with an ST-segment elevation of < 1 mm and a positive T wave. The type 2 and type 3 Brugada patterns are not specific enough to be considered diagnostic.[3] The Brugada pattern is a dynamic ECG finding and it may not always appear on 12-lead ECG. Because the disorder is a sodium channelopathy, it usually is reproduced by sodium channel blockers. A procainamide challenge test is used to establish the diagnosis[5]; however this test is not required if the type 1 Brugada pattern exists on the 12-lead ECG.

Because Brugada syndrome is an inherited condition, it is important to obtain a thorough family history of syncope, VT or SCD. Genetic testing of both the patient and family members for SCNA5 mutations is recommended. To establish a diagnosis of Brugada syndrome the patient should present with a type 1 Brugada ECG pattern (with or without procainamide challenge) and at least 1 of the following criteria: family history of SCD or family history of type 1 Brugada ECG change; documented VT or VF; inducibility of VT in an electrophysiology study (EPS); syncope or nocturnal agonal respiration.[2]

Treatment

Although a pharmacologic approach, such as treatment with amiodarone, has been shown to be effective to some degree, the implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) is the mainstay of the therapy. ICD therapy is recommended for patients with a type 1 Brugada ECG pattern who are symptomatic. Other etiologies for symptoms such as syncope, and seizure should be ruled out before considering these symptoms as being secondary to Brugada syndrome. For asymptomatic patients, Antzelevitch and colleagues[5] suggest dividing them into 2 main categories: (1) those with a spontaneously occurring type 1 Brugada pattern, and (2) those showing a type 1 Brugada pattern after procainamide challenge. EPS is recommended for all patients in group 1 and for patients in group 2 who have a family history of SCD. If any VT is inducible in EPS, an ICD should be implanted to prevent SCD.[5] Although this approach is recommended by some experts, risk stratification in Brugada syndrome is controversial. For instance the results of a recent meta-analysis of 30 prospective studies of Brugada syndrome suggests that a history of syncope or SCD, the presence of a spontaneous type I Brugada ECG pattern, and male gender carry poorer prognosis with more frequent events while a family history of SCD, the presence of an SCN5A gene mutation, or inducible VT in EPS may not have a prognostic value.[9]

Conclusion

Emergency physicians should be aware of Brugada ECG pattern in differential diagnosis of ST segment elevation in anterior precordial leads of ECG and associated VT/VF and SCD. In majority of the cases and especially in young patients consultation with a cardiologist or electrophysiologist is required. This report also points out the possibility of late presentation of Brugada syndrome and how it may change the management.

Although our patient's ECG was typical for type 1 Brugada pattern, she did not have any clinical criteria of the syndrome. Therefore the article presents a case with a type 1 ECG pattern characteristic of Brugada syndrome and not a Brugada syndrome. Our patient had no family history of SCD, Brugada syndrome or any syncopal events. Since she was unusually old for the presentation of Brugada syndrome and had experienced no cardiac event in her 77 years, she did not undergo EPS or ICD implantation.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: ST Segment Elevation on Electrocardiogram: The Electrocardiographic Pattern of Brugada Syndrome See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at Arash_52@yahoo.com or to Paul Blumenthal, MD, Deputy Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in MedGenMed via email: pblumen@stanford.edu

Contributor Information

Ali A. Sovari, Department of Cardiology, University of California, Los Angeles, California Author's email: Arash_52@yahoo.com.

Marilyn A. Prasun, Graduate School of Nursing, Millikin University, Decatur, Illinois.

Abraham G. Kocheril, University of Illinois, Chicago, Illinois.

References

- 1.Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1391–1396. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90253-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilde AA, Antzelevitch C, Borggerefe M, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for the Brugada syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1648–1654. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2002.3382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altzelevitch C, Brugada P, Brugada J, Brugada R. Brugada Syndrome: From Bench to Bedside. Boston, Mass: Blackwell Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sovari AA, Kocheril AG, Assadi R, Zareba W, Rosero S. Long QT syndrome. eMed J. 2005;6(6) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Brugada J, Brugada R. Brugada syndrome: from cell to bedside. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2005;30:9–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sovari AA, Prasun MA, Kocheril AG, Brugada R. Brugada syndrome unmasked by pneumonia. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33:501–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu W. The Brugada syndrome – an update. Intern Med. 2005;44:1224–1231. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuo K, Akahoshi M, Seto S, et al. Disappearance of Brugada-type Electrocardiogram after surgical castration: a role for testosterone and an explanation for the male predominance. PACE. 2003;26:1551–1553. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.t01-1-00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gehi AK, Duong TD, Metz LD, Gomes JA, Mehta D. Risk stratification of individuals with the Brugada electrocardiogram: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:577–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]