Abstract

This study was performed on 50 human embryos and fetuses between 7 and 17 weeks of development. Reichert's cartilage is formed in the second pharyngeal arch in two segments. The longer cranial or styloid segment is continuous with the otic capsule; its inferior end is angulated and is situated very close to the oropharynx. The smaller caudal segment is in contact with the body and greater horn of the hyoid cartilaginous structure. No cartilage forms between these segments. The persistent angulation of the inferior end of the cranial or styloid segment of Reichert's cartilage and its important neurovascular relationships may help explain the symptomatology of Eagle's syndrome.

Keywords: Eagle's syndrome, human embryology, pharyngeal arches, Reichert's cartilage

Introduction

Reichert's cartilage has been described as a continuous cartilaginous formation in the second pharyngeal arch and is the origin of several structures such as the styloid process of the temporal bone, the stylohyoid ligament and the lesser horns of the hyoid bone. The styloid process of the temporal bone is formed by the ossification of Reichert's cartilage; the portion of this cartilage between the styloid process and the lesser horn of the hyoid bone forms the stylohyoid ligament (Hamilton & Mossman, 1975; Corliss, 1979; Sperber, 1989; O’Rahilly & Müller, 1996; Sadler, 1996; Abramovich, 1997; Moore & Persaud, 1999; Avery, 2002; Larsen, 2003; Carlson, 2005) and corresponds to the cartilaginous segment called the ceratohyal segment (Stafne & Hollinshead, 1962; Frommer, 1974; Balbuena et al. 1997).

The styloid process and the stylohyoid ligament have been linked to Eagle's syndrome, which has a symptomatology characterized by the sensation of having a foreign body in the pharynx, causing difficult and painful swallowing and earache (Eagle, 1937, 1948, 1949, 1958). It has also been referred to as: styloid syndrome or stylohyoid syndrome (Steinman, 1968; Ettinger & Hanson, 1975; Messer & Abramson, 1975; Gossman & Tarsitano, 1977), stylalgia (Patni et al. 1986), stylohyoid disorder (Schroeder, 1991), neuralgia of the styloid process (Langland et al. 1982), symptomatic mineralization of the stylohyoid–stylomandibular complex (MSSLC) (Correll et al. 1979) and cervicopharyngeal pain syndrome (Camarda et al. 1989a,b; Kay et al. 2001). In addition to the aforementioned symptomatology, it can also cause a lateral sore throat, vertigo, carotidynia, tinnitus, dysphonia (Correl & Wescott, 1982; Camarda et al. 1989a,b), pain on turning the head (Babad, 1995), reduced mandibular opening (Diamond et al. 2001), changes in voice, pain on extending the tongue, hypersalivation sensation (Strauss et al. 1985; Baugh & Stocks, 1993) and even alterations in taste (Baddour et al. 1978; Kay et al. 2001). Studies on the aetiology of this syndrome have consistently reported an elongated styloid process (Dwight, 1907; Balasubramanian, 1964; Lavine et al. 1968; Porrath, 1969; Goodman, 1981; Solfanelli et al. 1981; O’Carroll, 1984; Patni et al. 1986; Camarda et al. 1989a,b; Carroll, 1993; Blomgren et al. 1999; Satyapal & Kalideen, 2000; Kay et al. 2001). A long styloid process is found in 1–4% of the population (Eagle, 1958; Kaufman et al. 1970; Handa, 1971), although 7.8% (Correll et al. 1979) or 10.3% (Kaufman et al. 1970) present symptomatology. The length of the adult styloid process is variable, and according to Frommer (1974), the mean length is 3.17 cm; Yetiser et al. (1997) describe a normal length of 1.5–2.5 cm; and Ferrario et al. (1990), reported from X-ray measurements that the normal adult styloid process has a mean length between 2.5 and 3.2 cm.

A longer styloid process has been interpreted as being due to calcification or ossification of the stylohyoid ligament (Dwight, 1907; Graf, 1959; Balasubramanian, 1964; Lavine et al. 1968; Porrath, 1969; Kaufman et al. 1970; Goldstein & Scopp, 1973; Frommer, 1974; Boedts, 1978; Correl et al. 1979; McGinnis, 1981; Goodman, 1981; Solfanelli et al. 1981; O’Carroll, 1984; Monsour & Young, 1986; Patni et al. 1986; Ruprecht et al. 1988; Camarda et al. 1989a,b; Ferrario et al. 1990; Baugh & Stocks, 1993; Carroll, 1993; Fanibunda & Lovelock, 1997; Ommell et al. 1998; Blomgren et al. 1999; Bafaqeeh, 2000; Satyapal & Kalideen, 2000; Kay et al. 2001). Several theories have been proposed to explain calcification of the stylohyoid ligament. These include degenerative changes undergone by the fibres of the stylohyoid ligament (Shenoi, 1972), metaplasic alterations due to a traumatic stimulus that induces ossification of the stylohyoid ligament (Steinman, 1970), either due to an anatomical variation in which the stylohyoid ligament is ossified in early stages (Steinman, 1970) or even to what Montalbetti et al. (1995) referred to as ‘regressive ontogenetic development’, where the stylohyoid ligament contains cartilaginous remains that are later ossified. These opinions still are considered controversial among authors who do not believe that there is enough objective evidence to support them.

The main objective of our study was to examine the morphology and relationships of Reichert's cartilage. This analysis is important as it may help to explain the symptomatology of Eagle's syndrome.

Materials and methods

Fifteen embryos and 35 human fetuses from the collection of the Embryology Institute of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid were studied. In the embryos, crown–rump length (CRL) ranged from 18.5 to 31 mm (O’Rahilly stages 20–23) (Table 1). In the fetuses, CRL ranged from 38 to 150 mm (weeks 9–17 of development) (Table 2). The parameters used to determine gestational age were CRL, weight and cranial perimeter (O’Rahilly & Müller, 1996). All specimens were obtained from ectopic pregnancies or spontaneous abortions, and no part of the material gave indications of possible malformation. Approval for the study was granted by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University Complutense of Madrid.

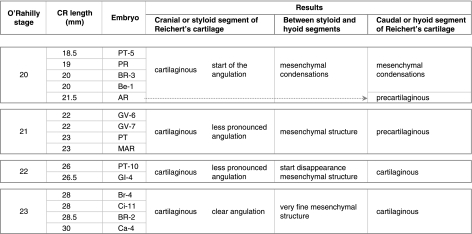

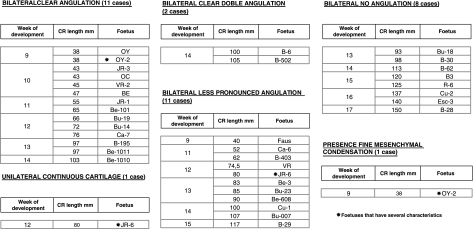

Table 1.

Details of the embryonic period

Table 2.

Details of the fetal period

All specimens were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin for processing. Sections were 7–25 µm thick, depending on specimen size. Sections were stained with haematoxylin–eosin, azan, azocarmine, and Bielschowsky and Masson's trichromic dye (McManus & Mowry, 1968). The study was carried out using a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope and a Nikon DXM 1200 digital camera coupled to a Pentium IV PC.

The nomenclature used corresponds to the English version of the Terminologica Anatomica of the Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology (FCAT, 2001).

Results

Embryonic period

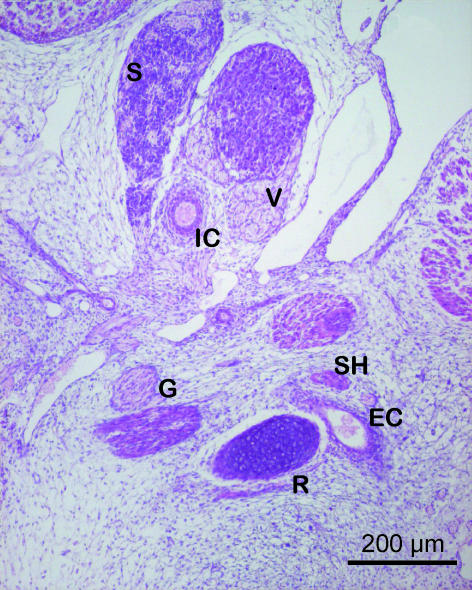

According to our observations, a well-defined cartilaginous structure has developed in the superior segment of the second pharyngeal arch in human embryos of O’Rahilly's stage 20 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Human embryo GV-6 (22 mm CRL). Frontal section. Haematoxylin–eosin staining. Cranial segment of Reichert's cartilage (R), connected with the external carotid artery (EC), lying between Reichert's cartilage and the stylohyoid muscle (SH). The vasculonervous elements of the retrostyloid space are dorsal to Reichert's cartilage: glossopharyngeal nerve (G), vagus nerve (V), internal carotid artery (IC), superior cervical ganglion (S).

This adopts an elongated morphology and crosses the pharyngeal arch in a caudoventromedial direction. The cranial end of this cartilaginous structure is curved in a hook shape, is joined to the side of the otic capsule and resembles a prolongation from it (Fig. 2A).

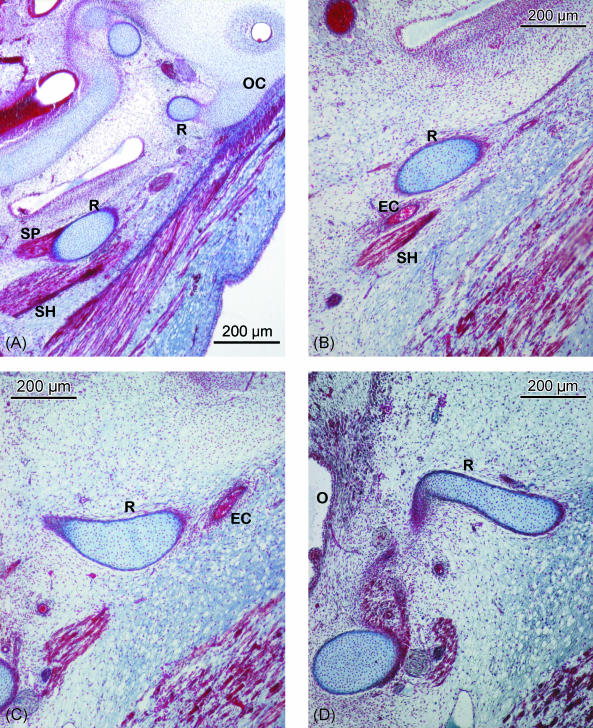

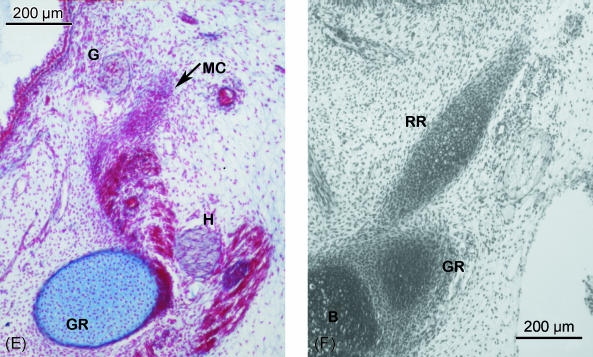

Fig. 2.

(A–E) Human embryo BR-4 (28 mm CRL). Frontal sections. Azocarmine staining. (A) Hooked superior end of Reichert's cartilage (R) showing its continuity with the otic capsule (OC); due to the caudoventromedial direction of the cartilage, this is also sectioned caudally at the origin of the stylopharyngeal (SP) and stylohyoideal (SH) muscles. (B) The external carotid artery (EC) passing between Reichert's cartilage (R) and the stylohyoid muscle (SH). (C) The start of the angulation of the inferior end of the cranial segment of Reichert's cartilage (R). External carotid artery (EC). (D) Change in direction of the lower end of the cranial segment of Reichert's cartilage (R) orientated towards the oropharynx (O). (E) Mesenchymal condensation (MC), which continues caudally to the cranial segment of Reichert's cartilage clearly distinguished from the cartilage of the third pharyngeal arch (greater horn of the hyoid cartilaginous structure) (GR). Glossopharyngeal nerve (G). Hypoglossal nerve (H). (F) Human embryo BR-2 (28.5 mm CRL). Frontal section. Haematoxylin–eosin staining. Caudal or hyoid segment of Reichert's cartilage (RR) in contact with the body (B) and the greater horn (GR) of the hyoid cartilaginous structure.

In the area where the external carotid artery passes through the space between Reichert's cartilage and the tendon where the stylohyoid muscle originates, Reichert's cartilage changes direction and becomes angulated with its end pointing towards the midline (Fig. 2B–D).

Caudal to this area, Reichert's cartilage is continuous with a mesenchymal cellular condensation where the cartilage has not formed. This mesenchymal structure, which forms an extension of Reichert's cartilage, is separated from the angle of the mandible by the styloglossus muscle and can be clearly distinguished from the cartilage of the third pharyngeal arch (Fig. 2E). The mesenchymal condensation extends from Reichert's cartilage to the hyoid cartilaginous structure, finishing at the area where the body joins the greater horn.

At the end of the embryonic period, the small portion of the mesenchymal structure that terminates in the hyoid cartilaginous formation has been changed into cartilage (Fig. 2F). At the end of the embryonic period, the cartilage of the second pharyngeal arch adopts the following arrangement:

Cranial or styloid segment, longer and larger. This cartilaginous segment has two ends: the superior end, joined to the otic capsule, and the inferior end, which is angulated. This clear angulation occurs where the cartilage is in close proximity with the external carotid artery (Fig. 2A–D).

Caudal or hyoid segment. This short cartilaginous segment terminates caudally in the hyoid cartilaginous structure between the body and the greater horn (Fig. 2F).

We found that between each segment no cartilage had formed. There is a mesenchymal condensation that joins the cranial segment with the caudal segment (Fig. 2E). Table 1 summarizes the most important results found for the embryonic period.

Fetal period

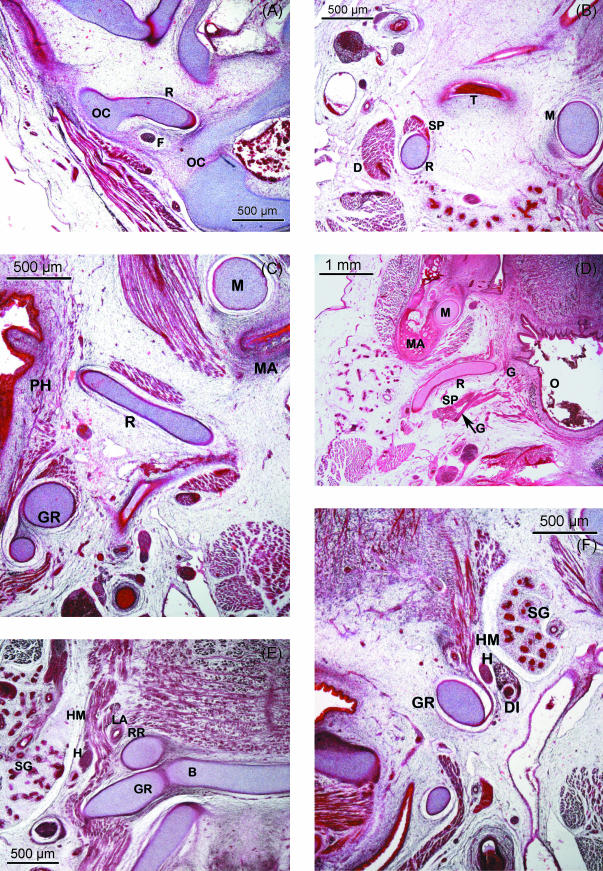

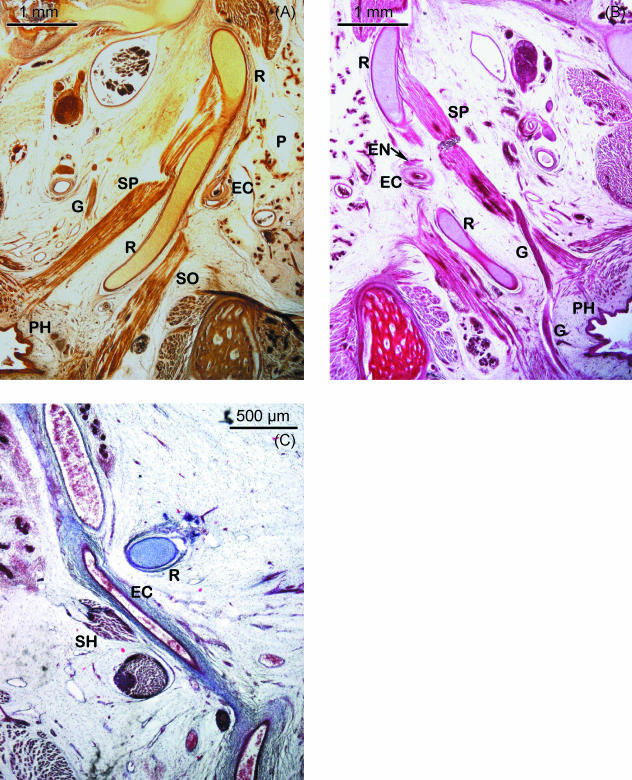

During the fetal period, the superior end of the hook-shaped cranial or styloid segment of Reichert's cartilage is still continuous with the inferior extension of the otic capsule. Both structures contribute to form the vertical portion of the facial nerve canal (Fig. 3A). Caudally, this segment of Reichert's cartilage is related to the tympanic bone (Fig. 3B) and its first segment is orientated in a caudoventromedial direction (Fig. 3B). This is followed by another segment that forms an angulation with the previous one that adopted a horizontal position (Fig. 3C). This angulation, previously observed in the embryonic period, is located dorsally to the mandibular angle with its end pointing towards the oropharynx (Fig. 3D). Its most important relationship in this region is with the glossopharyngeal nerve. After crossing the inferior surface of the stylopharyngeal muscle, this nerve lies medial to the angulated end of Reichert's cartilage, running between this structure and the pharyngeal wall (Figs 3D and 4B).

Fig. 3.

(A–C) Human fetus JR-1 (55 mm CRL). Transverse sections. Azocarmine staining. (A) Superior end of the cranial segment of Reichert's cartilage (R), joined to the otic capsule (OC) and forming with this the vertical portion of the facial canal. Facial nerve (F). (B) Reichert's cartilage (R) is related to the tympanic part of the temporal bone (T) that separates it from Meckel's cartilage (M). The stylopharyngeal muscle (SP) originates in Reichert's cartilage; dorsally is the posterior belly of the digastric muscle (D). (C) Angulated inferior portion of the cranial segment of Reichert's cartilage (R), situated dorsal to the mandibular angle (MA). The angulated end touches the pharyngeal wall (PH). Greater horn of the hyoid cartilaginous structure (GR). Meckel's cartilage (M). (D) Human fetus Bu-14 (72 mm CRL). Transverse section. Haematoxylin–eosin staining. Inferior portion of the cranial segment of Reichert's cartilage (R). This presents a clear angulation dorsomedial to the mandibular angle (MA). The glossopharyngeal nerve (G) close to the stylopharyngeal muscle (SP) and with the angulated end of Reichert's cartilage (R). Meckel's cartilage (M). Oropharynx (O). (E) Human fetus Be-101 (65 mm CRL). Frontal section. Azocarmine staining. Caudal segment of Reichert's cartilage (RR) that will form the lesser horn of the hyoid cartilaginous formation, situated between the body (B) and the greater horn (GR). Hypoglossal nerve (H). Hyoglossus muscle (HM). Lingual artery (LA). Submandibular gland (SG). (F) Human fetus JR-1 (55 mm CRL). Azocarmine staining. Transverse section at the lateral suprahyoid region where Reichert's cartilage does not form. The hyoglossus muscle (HM) originates in the greater horn (GR) of the hyoid cartilaginous formation. The hypoglossus nerve (H) and the intermediate tendon of the digastric muscle (DI) run laterally to the hyoglossus muscle. The submandibular gland (SG) lies laterally to these structures.

Fig. 4.

(A,B) Human fetus Be-608 (90 mm CRL). Transverse section. Bielschowsky staining. (A) Cranial segment of Reichert's cartilage (R) that presents a less pronounced angulation. Lateral to the cartilage, the external carotid artery (EC), the parotid gland (P) and the styloglossus muscle (SO) can be observed. The stylopharyngeal muscle (SP) and the glossopharyngeal nerve (G) are medial to the cartilage. Pharynx (PH). (B) Haematoxylin–eosin staining. Relationships between the cranial segment of Reichert's cartilage (R) and the external carotid artery (EC) and the external carotid nerves (EN) that surround it and with the glossopharyngeal nerve (G) situated between the end of the cartilage and the pharynx (PH). Stylopharyngeal muscle (SP). (C) Human fetus JR-6 (80 mm CRL). Frontal section. Azocarmine staining. The external carotid artery (EC) can be observed in the space formed between Reichert's cartilage (R) and the stylohyoid muscle (SH) situated laterally.

At a post-conception age of 13 weeks, the angulation of the inferior end of the cranial or styloid segment may vary, giving rise to different degrees of angulation ranging from barely visible to extreme (Table 2; Figs 3C,D and 4A,B). The lengths of this segment are also variable, giving rise to cranial segments that are closer to or further from the mandibular angle. The caudal segments of Reichert's cartilage are found on both sides of the cartilaginous hyoid body with which they are in contact, constituting the lesser horns (Fig. 3E).

Between the cranial segment of Reichert's cartilage, which will form the styloid process, and the segment that will constitute the lesser horn, no cartilage was found to have formed in the second arch, except in one case which presented a unilateral continuous cartilage on the left side (Table 2). The mesenchymal condensation, which was present in the embryonic period, was observed at the start of the fetal period, but it then disappears and leaves no trace during the rest of the fetal period (Fig. 3F).

During the fetal period studied, Reichert's cartilage was found to have three noteworthy relationships:

With the pharynx, when angulation of the inferior end of the cranial or styloid segment persisted. Depending on the degree of angulation, the end of the cartilage may be very close to the pharyngeal wall (Figs 3C,D and 4B).

With the glossopharyngeal nerve. This nerve crosses medial to the inferior end of the cranial segment. The more angulated this segment the closer the nerve crosses to its end (Figs 3D and 4B).

With the external carotid artery. The artery surrounded by the external carotid nerves passes through the hiatus or space defined by Reichert's cartilage and the stylohyoid muscle. This takes place where Reichert's cartilage changes direction and begins to angulate (Fig. 4A–C).

During the fetal period studied we did not find any differences in the morphological arrangement of the cartilage from each side in the same specimen. We observed only one case with a unilateral continuous cartilage. Table 2 summarizes the most important results found for the fetal period.

Discussion

At the end of the embryonic period the cartilage of the second pharyngeal arch or Reichert's cartilage was found to have formed only in the superior and inferior segments of the arch. The longer cranial or styloid segment was continuous with the otic capsule. The shorter caudal segment was in contact with the hyoid cartilaginous formation. No cartilage had formed between these two segments, but a mesenchymal tissue was faintly seen to join the two cartilaginous segments. This morphological arrangement has not been described previously. We therefore consider that Reichert's cartilage does not constitute a continuous element, in contrast to the cartilage of the first pharyngeal arch or Meckel's cartilage (Rodríguez-Vázquez et al. 1992, 1997).

From our observations, in the central part of the second pharyngeal arch, Reichert's cartilage does not degenerate to fibrous tissue, because in the cases studied (with one exception) it can be deduced that in general Reichert's cartilage does not develop here. In human development therefore there is no formation of a cartilaginous segment termed the ceratohyal (Lesoine, 1966; Stafne & Hollinshead, 1968; Arnould et al. 1969; Ommell et al. 1998) that, when it degenerates, leaves behind its fibrous sheath producing the stylohyoid ligament (Dwight, 1907; Stafne & Hollinshead, 1962; Hollinshead, 1969; Frommer, 1974; Hamilton & Mossman, 1975; Corliss, 1979; Sperber, 1989; Montalbetti et al. 1995; O’Rahilly & Müller, 1996; Sadler, 1996; Abramovich, 1997; Moore & Persaud, 1999). The embryological theory that the perichondrium of Reichert's cartilage forms the stylohyoid ligament, or serves as a guide for its formation (Hamilton & Mossman, 1975; Corliss, 1979; Sperber, 1989; O’Rahilly & Müller, 1996; Sadler, 1996; Abramovich, 1997; Moore & Persaud, 1999; Avery, 2002; Larsen, 2003; Carlson, 2005), should be studied again in light of our data.

In the fetal period, the morphology of Reichert's cartilage is clearly defined, presenting two areas or segments: one longer cranial segment that is joined to the otic capsule and the other shorter segment in contact with the hyoid cartilaginous structure. No cartilage forms between these two segments. We consider the existence of a unilateral continuous cartilage in one specimen to be exceptional and therefore to correspond to a variation. This could explain observations of isolated cases of complete stylohyoid chains (Satyapal & Kalideen, 2000; Gözil et al. 2001; Kay et al. 2001).

The suggestion made by Revilla & Stuyt (1989) that after the third intra-uterine month Reichert's cartilage is divided into five segments is totally at odds with our observations. In human development we have not observed the segmentation described to date of the stylohyoid apparatus: timpanohyal, stylohyal, ceratohyal and hypohyal (Lesoine, 1966; Stafne & Hollinshead, 1968; Arnould et al. 1969; Ommell et al. 1998). We observed only the cranial segment of Reichert's cartilage that would correspond to the stylohyal segment and that corresponding to the lesser horn or the hypohyal segment.

The morphology of the cranial or styloid segment of Reichert's cartilage is of interest. As described, its inferior end presents variable degrees of angulation. When this angulation was pronounced, the tip of the angulated part reached the oropharyngeal wall. These observations made in relation to the morphology of Reichert's cartilage have not been previously reported.

In our opinion, the variability in form and length of the cranial segment of Reichert's cartilage gives rise to a styloid process of variable length that can be inclined as observed by Loeser & Cardwell (1942), Frommer (1974), Baddour et al. (1978), Ghosh & Dubey (1999) and Thot et al. (2000). This is in accordance with research carried out by Lengele & Dhem (1989), which shows that both long and short styloid processes present the same characteristics of calcified cartilage. The relationships of the angulated inferior end of the cranial or styloid segment of Reichert's cartilage may explain the most frequent symptomatology associated with Eagle's syndrome. We consider that dysphagia and the sensation of a foreign body in the throat could be caused by the fact that the tip of the angulated end is sometimes very close to the pharyngeal wall. This is why Frommer (1974) observed that the direction and curvature of the styloid process were more important than its length.

The sore throat and pain around the area of distribution of the glossopharyngeal nerve (Loeser & Cardwell, 1942; Eagle, 1948; Shenoi, 1972; Frommer, 1974), and even the possible alterations in taste (Baddour et al. 1978; Kay et al. 2001), would be explained by the close association we have demonstrated between the nerve and Reichert's cartilage. According to Graf (1959), while swallowing, the glossopharyngeal nerve could be pushed against the osseous spicule and be stimulated, producing a paroxysmal pain.

Carotid artery syndrome (Eagle, 1948), a piercing pulsating pain in the side of the neck, which could be triggered on moving the neck (Koebke, 1976), would be explained by the relationship between Reichert's cartilage and the external carotid artery and the external carotid nerves that surround it.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to Mrs Montserrat Juanilla for her technical assistance in the preparation of this paper.

References

- Abramovich A. Embriología de la región maxilofacial. Buenos Aires: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Arnould G, Tridon P, Laxenaire M, Picard L, Weber M, Masingue M. Appareil stylo-hyoïdien et malformations de la charnière occipito-vertébrale. A propos de cinq observations. Rev Otoneuroophtalmol. 1969;41:190–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery JK. Oral Development and Histology. 3. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Babad MS. Eagle's syndrome caused by traumatic fracture of a mineralized stylohyoid ligament. Literature review and a case report. Cranio. 1995;13:188–192. doi: 10.1080/08869634.1995.11678067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddour HM, McAnear JT, Tilson HB. Eagle's syndrome. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978;46:486–494. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(78)90378-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bafaqeeh SAF. Eagle syndrome: classic and carotid artery types. J Otolaryngol. 2000;29:88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian S. The ossification of the stylohyoid ligament and its relation to facial pain. Br Dent J. 1964;116:108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Balbuena L, Hayes D, Ramirez SG, Johnson R. Eagle's syndrome (elongated styloid process) South Med J. 1997;90:331–334. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199703000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh RF, Stocks RM. Eagle's syndrome: a reappraisal. ENT J. 1993;72:341–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomgren K, Qvarnberg Y, Valtonen H. Spontaneous fracture of an ossified stylohyoid ligament. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:854–855. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100145402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boedts D. Styloid process syndrome or stylohyoid syndrome? Acta Otorhino-Lar Bel. 1978;32:277–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarda AJ, Deschamps C, Forest D. I. Stylohyoid chain ossification: a discussion of etiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989a;67:508–514. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarda AJ, Deschamps C, Forest D. II. Stylohyoid chain ossification: a discussion of etiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989b;67:515–520. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BM. Embriología humana y biología del desarrollo. Madrid: Elsevier España S.A; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JJ. Osteoarthrosis, the temporomandibular joint and Eagle's syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;75:273–275. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90133-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comité Federal sobre Terminología Anatómica (FCAT) Terminología Anatómica. Madrid: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Corliss CE. Embriología humana de PattenFundamentos del desarrollo clínico. Buenos Aires: El Ateneo; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Correll RW, Jensen JL, Taylor JB, Rhyne RR. Mineralization of the stylohyoid–stylomandibular ligament complex: a radiographic incidence study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1979;48:286–291. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(79)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correl RW, Wescott WB. Eagle's syndrome diagonosed after history of headache, dysphagia, otalgia, and limited neck movement. J Am Dent Assoc. 1982;104:491–492. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1982.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond L, Cottrell D, Hunter M, Papageorge M. Eagle's syndrome: a report of 4 patients treated using a modified extraoral approach. J Oral Maxilofac Surg. 2001;59:1420–1426. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.28276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwight T. Stylo-hyoid ossification. Ann Surg. 1907;46:721–735. doi: 10.1097/00000658-190711000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle WW. Elongated styloid process. Arch Otolaryngol. 1937;25:584–587. [Google Scholar]

- Eagle WW. Elongated styloid process. Arch Otolaryngol. 1948;47:630–640. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1948.00690030654006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle WW. Symptomatic elongated styloid process. Arch Otolaryngol. 1949;49:490–503. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1949.03760110046003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle WW. Elongated styloid process. Arch Otolaryngol. 1958;67:172–176. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1958.00730010178007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger RL, Hanson JG. The styloid or Eagle syndrome: an unexpected consequence. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975;40:336–339. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(75)90416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanibunda K, Lovelock DJ. Calcified stylohyoid ligament: unusual pressure symptoms. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1997;26:249–251. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario VF, Sigurtá D, Daddona A, et al. Calcification of the stylohyoid ligament: incidence and morphoquantitative evaluations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:524–529. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90390-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frommer J. Anatomic variations in stylohyoid chain and their possible clinical significance. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1974;38:659–667. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(74)90382-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh L, Dubey S. The syndrome of elongated styloid process. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1999;26:169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(98)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein GR, Scopp IW. Radiographic interpretation of calcified stylomandibular and stylohyoid ligaments. J Prosthet Dent. 1973;30:330–334. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(73)90192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RS. Fracture of an ossified stylohyoid ligament. Arch Otolaryngol. 1981;107:129–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossman JR, Jr, Tarsitano JJ. The styloid–stylohyoid syndrome. J Oral Surg. 1977;35:555–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gözil R, Yener N, Çalguner E, Araç M, Tunç E, Bahcelioglû M. Morphological characteristics of styloid process evaluated by computerized axial tomography. Ann Anat. 2001;183:527–535. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(01)80060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf CJ. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia and ossification of the stylohyoid ligament. J Neurosurg. 1959;16:448–453. doi: 10.3171/jns.1959.16.4.0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton WI, Mossman HW. Embriología Humana. 4. Buenos Aires: Intermédica; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Handa PS. Elongated styloid process (a case report) Ind J Otolaryng. 1971;23:36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hollinshead WH. Textbook of Anatomy. New York: Harper & Row; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman SM, Elzay RP, Irish EF. Styloid process variation: radiologic and clinical study. Arch Otolaryngol. 1970;91:460–463. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1970.00770040654013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay DJ, Har-El G, Lucente FE. A complete stylohyoid bone with a stylohyoid joint. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22:358–361. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2001.26497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koebke J. Kompression der A. Carotis externa. Ein anatomischer Befund zum Eagleschen Syndrom. Laryng Rhinol. 1976;55:913–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langland OE, Langlais RP, Morris CR. Principle and Practice of Panoramic Radiology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen JW. Embriología Humana. Madrid: Elsevier España S.A.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lavine MH, Stoopack JC, Jerrold TL. Calcification of the stylohyoid ligament. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968;25:55–58. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(68)90197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengele B, Dhem A. Microradiographic and histological study of the styloid process of the temporal bone. Acta Anat. 1989;135:193–199. doi: 10.1159/000146753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesoine W. Anomalien der Zungenbeinkette. HNO. 1966;14:70–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeser LH, Cardwell EP. Elongated styloid process. A cause of glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Arch Otolaryngol. 1942;36:198–202. [Google Scholar]

- McGuinnis JM., Jr Fracture of an ossified stylohyoid bone. Arch Otolaryngol. 1981;107:460. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1981.00790430062022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus JFA, Mowry RW. Técnica Histológica. Madrid: Atika S.A.; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Messer EJM, Abramson AM. The styloid syndrome. J Oral Surg. 1975;33:664–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsour PA, Young WG. Variability of the styloid process and stylohyoid ligament in panoramic radiographs. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61:522–526. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalbetti L, Ferrandi D, Pergani P, Savoldi F. Elongated styloid process and Eagle's syndrome. Cephalalgia. 1995;15:80–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1995.015002080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KL, Persaud TVN. Embriología Clínica. 6. México: McGraw-Hill Interamericana; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- O'Carroll MK. Calcification in the stylohyoid ligament. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:617–621. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ommell KAH, Gandhi C, Ommell ML. Ossification of the human styloid ligament. A longitudinal study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol End. 1998;85:226–232. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90431-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rahilly R, Müller F. Human Embryology and Teratology. 2. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Patni VM, Gadewar DR, Pillai KG. Ossification of stylohyoid ligament with pseudojoint formation. A case report. J Indian Dent Assoc. 1986;58:227–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrath S. Roentgenologic considerations of the hyoid apparatus. Acta Radiol. 1969;105:63–73. doi: 10.2214/ajr.105.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revilla C, Stuyt MT. El síndrome estiloides. A propósito de tres casos. An Otorrinolaringol Ibero Am. 1989;16:659–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Vázquez JF, Mérida-Velasco JR, Jiménez-Collado J. Development of the human sphenomandibular ligament. Anat Rec. 1992;233:453–460. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092330312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Vázquez JF, Mérida-Velasco JR, Mérida-Velasco JA, Sánchez-Montesinos I, Espín-Ferra J, Jiménez-Collado J. Development of Meckel's cartilage in the symphyseal region in man. Anat Rec. 1997;249:249–254. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199710)249:2<249::AID-AR12>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruprecht A, Sastry KARH, Gerard P, Mohammad AR. Variation in the ossification of the stylohyoid process and ligament. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1988;17:61–66. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.1988.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler TW. Langman Embriología Médica. 7. Buenos Aires: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Satyapal KS, Kalideen JM. Bilateral styloid chain ossification: case report. Surg Radiol Anat. 2000;22:211–212. doi: 10.1007/s00276-000-0211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder WA. Traumatic Eagle's syndrome. Otolaryngology. 1991;104:371–374. doi: 10.1177/019459989110400314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoi PM. Stylohyoid syndrome. J Laryngol. 1972;86:1203–1211. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100076428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solfanelli SX, Braun TH, Soteranos GC. Surgical management of a symptomatic fractured, ossified stylohyoid ligament. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1981;52:569–573. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(81)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber GH. Craniofacial Embryology. 4. Cambridge: Wright; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stafne EC, Hollinshead WH. Roentgenographic observations on the styloid chain. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1962;15:1195–1200. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(62)90154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafne EC, Hollinshead WH. Roentgenographic observations on the stylohyoid ligament. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968;25:55–58. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(62)90154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman EP. Styloid syndrome in absence of an elongated process. Acta Otolaryngol. 1968;66:347–356. doi: 10.3109/00016486809126301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman EP. A new light on the pathogenesis of the styloid syndrome. Arch Otolaryngol. 1970;91:74–75. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1970.00770040241013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss M, Zohar Y, Laurian N. Elongated styloid process syndrome: intraoral versus external approach for styloid surgery. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:976–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thot B, Revel S, Mohandas R, Rao AU, Kumar A. Eagle syndrome: classics and carotid artery types. J Otolaryngol. 2000;29:88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yetiser S, Gerek M, Ozkaptan Y. Elongated styloid process: diagnostic problems related to symptomatology. Cranio. 1997;15:236–241. doi: 10.1080/08869634.1997.11746017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]