Abstract

Adult craniofacial morphology results from complex interactions among genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors. Trisomy causes perturbations in the genetic programmes that control development and these are reflected in morphology that can either ameliorate or worsen with time and growth. Many of the specific changes that occur in Down syndrome can be studied in the Ts65Dn trisomic mouse, which shows direct parallels with specific aspects of adult craniofacial dysmorphology associated with trisomy 21. This study investigates patterns of craniofacial growth in Ts65Dn mice and their euploid littermates to assess how the adult dysmorphology develops. Three-dimensional coordinate data were collected from microcomputed tomography scans of the face, cranial base, palate and mandible of newborn (P0) and adult trisomic and euploid mice. Growth patterns were analysed using Euclidean distance matrix analysis. P0 trisomic mice show significant differences in craniofacial shape. Growth is reduced along the rostro-caudal axis of the Ts65Dn face and palate relative to euploid littermates and Ts65Dn mandibles demonstrate reduced growth local to the mandibular processes. Thus, the features of Down syndrome that are reflected in the mature Ts65Dn skull are established early in development and growth does not appear to ameliorate them. Differences in growth may in fact contribute to many of the morphological differences that are evident at birth in trisomic mice and humans.

Keywords: 3D microcomputed tomography, aneuploidy, craniofacial morphology, Down syndrome, growth, landmark analysis, mouse, Trisomy 21

Introduction

Down syndrome (DS) results from trisomy of human chromosome 21 (Hsa21). The hundreds of genes at dosage imbalance are presumed to affect a wide range of developmental pathways and their target tissues. Many traits are associated with DS, but most occur in only a subset of people with trisomy 21. However, the characteristic craniofacial appearance, which is due substantially to dysmorphology of the underlying craniofacial skeleton, is among the few traits consistently found in all individuals with DS (Reeves et al. 2001). Individuals with DS also demonstrate reduced postnatal growth of the craniofacial complex relative to unaffected individuals (Kisling, 1966; Rarick et al. 1975; Cronk & Reed, 1981; Fischer-Brandies, 1988; Myrelid et al. 2002; Bagic & Verzak, 2003). Adult craniofacial morphology is the result of complex interactions among genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors that occur during ontogeny (Atchley & Hall, 1991). Elucidation throughout development of the patterns of dysmorphogenesis that produce the final adult form can provide information to distinguish the influences of these various factors on adult craniofacial shape.

The Ts65Dn mouse is an established model for DS (Davisson et al. 1993; Reeves et al. 1995). These mice are trisomic for a 15.6-Mb segment of mouse chromosome 16 (Mmu16) containing approximately 108 of the 247 genes shared between Mmu16 and Hsa21 (Antonarakis et al. 2004). The trisomic genes in the Ts65Dn mouse correspond closely in order and identity to those on Hsa21 (Reeves et al. 1998, 2001). We and others have demonstrated that this mouse model expresses a number of features with direct parallels to DS, including changes in cerebellar size and cellular architecture (Baxter et al. 1998, 2000; Olson et al. 2004a), visiospatial learning impairments (Escorihuela et al. 1995; Reeves et al. 1995; Hyde et al. 2001), small stature/reduced weight gain during growth (Roper et al. 2006) and age-related degeneration of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (Holtzman et al. 1996; Cooper et al. 2001). Adult Ts65Dn mice also demonstrate precise anatomical changes affecting size and shape of the skull that are analogous to those in DS (Richtsmeier et al. 2000). These include significant reductions in the rostro-caudal dimensions of the cranial base and palate and brachycephaly. The comparable genetic basis and corresponding anatomical findings validate the use of Ts65Dn mice as a model for evaluation of the contribution of postnatal craniofacial growth to craniofacial phenotypes produced by trisomy.

Complex morphological structures are continually changing. An important element of these changes is the way in which component structures rearrange relative to one another with overall increase in size. Much of this rearrangement is reflected in growth pattern, defined as the composite of geometric changes in structure occurring through time (Richtsmeier & Lele, 1993). The growth pattern consists of the directions and magnitudes of changes in component parts of the organism. Characterization of growth in a way that allows comparison of growth patterns between organisms is a logical step in determining how developmental patterns contribute to the maintenance of given morphologies and to the production of morphological variation. Here we evaluate differences in postnatal growth patterns of the skull measured quantitatively in Ts65Dn mice and euploid littermates to provide further information pertaining to the production of DS craniofacial phenotypes. Quantitative data describing skull phenotypes for P0 and adult mice support analysis to reveal differences in growth. Since craniofacial anomalies in adult Ts65Dn mice parallel those that differentiate DS individuals from the unaffected population, analysis of the growth patterns in Ts65Dn mice can determine if changes in the patterns of postnatal growth are also conserved between mouse and human, and allows detailed description of those changes.

Materials and methods

Animal husbandry and image acquisition

Trisomic B6EiC3Sn a/A-T(16C3-4;17A2)65Dn/J (Ts65Dn mice) females acquired from Jackson Laboratory (Davisson et al. 1993) were crossed with (B6J × C3HeJ)F1 male mice to produce euploid and trisomic progeny as described (Baxter et al. 1998, 2000; Richtsmeier et al. 2000). Ploidy was determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of cultured peripheral lymphocytes (Moore et al. 1999). In this study we analyse 35 adult mice (21 euploid and 14 trisomic) and 19 P0 mice (nine euploid and ten trisomic). Both male and female mice were included in the analysis as we have previously demonstrated that this model does not show significant sexual dimorphism of cranial metrics (Richtsmeier et al. 2000). All animal husbandry procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Carcasses of adult mice 4–6 months of age were skinned, eviscerated and stripped of excess neural and muscular structures and placed in a Dermestid beetle colony for cleaning. Skeletonization of P0 skulls would result in loss of anatomical integrity through disarticulation as most cranial sutures emerge as wide gaps between bones at this age. Accordingly, microcomputed tomography (micro-CT) was used to obtain 3D morphological data from the P0 mice. Intact P0 carcasses were stored in a 25% glycerin solution in sealed glass vials. Micro-CT images of the heads of P0 mice were acquired at the Center for Quantitative Imaging at the Pennsylvania State University (http://www.cqi.psu.edu) using the HD-600 OMNI-X high-resolution X-ray computed tomography system (Bio-Imaging Research Inc, Lincolnshire, IL, USA). Serial cross-sectional scans were collected in the coronal plane with slice thicknesses ranging from 0.0177 to 0.0200 mm (z dimension) with an average pixel size of 0.033 mm (x and y dimension; range: 0.0328–0.0370 mm).

Landmark data collection and analysis

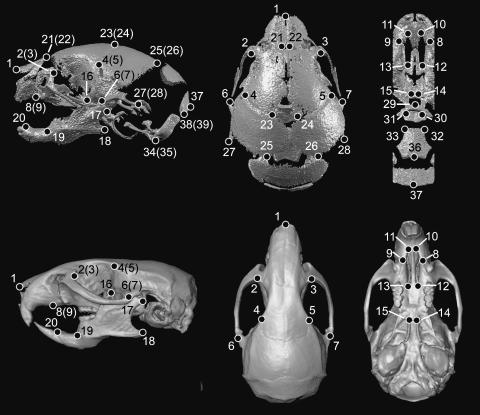

Three-dimensional coordinate locations of 20 biologically relevant landmarks located on the palate, face and mandible were recorded for P0 and adult mice (Fig. 1). Suture patency and limited ossification in the P0 neurocranium prevented the collection of certain landmarks (e.g. bregma). For growth analyses we were limited to those landmarks that could be identified with acceptable precision and accuracy on both adult and P0 skulls. An additional 19 landmarks were used in the investigation of shape of the P0 trisomic skull. A more complete list of landmarks and landmark definitions for each age group can be found on the Richtsmeier laboratory website (http://getahead.psu.edu).

Fig. 1.

Landmarks used in growth analysis and form analysis. Shown are 3D reconstruction of micro-CT scans of P0 (top) and adult (bottom) mouse crania showing lateral (left), superior (middle) and inferior (right) views. Landmarks used in analysis of growth difference were fully visible on both adult and P0 skulls. Growth analysis landmarks include: 1, nasale; 2(3), right (left) intersection of frontal process of maxilla with frontal and lacrimal bones; 4(5), most superior point on the squamous temporal at the intersection of the coronal suture; 6(7), intersection of zygomatic (jugal) bone with zygomatic process of temporal, superior aspect; 8(9), most inferior point on premaxilla–maxilla suture; 10(11), most anterior point of the palatine foramen; 12(13), most posterior point of the palatine foramen; 14(15), indentation lateral to posterior nasal spine; 16, coronoid process; 17, posterior-most of condyle; 18, angular process; 19, mandibular foramen; 20, superior-most point on the incisor alveolar ridge. Landmarks used to study form difference in P0 mice include those listed for growth analysis (above) and the addition of the following landmarks visible only on P0 mice: 21(22), posterior–medial point on nasal bone; 23(24), medial intersection of frontal and parietal bones at suture; 25(26), medial–posterior point of parietals; 27(28), most posterior point of squasmosal; 29, most anterior–medial point on the body of basisphenoid; 30(31), posterior tip of the medial pterygoid process; 32(33), antero lateral-most point on corner of the basioccipital; 34(35), lateral inferior process of the occipital condyle; 36, basion; 37, opisthion; 38(39), most infero-lateral point on the squamous occipital. Landmarks 21–39 were used exclusively in the form analysis between P0 trisomic and euploid mice.

Two different means of collecting 3D landmark coordinate data were used. Landmark data were collected from the skulls of adult mice using the Reflex microscope (http://www.reflexmeasurement.co.uk) as described in Richtsmeier et al. (2000). Landmark coordinate data were collected from 3D reconstructions of micro-CT images of P0 skulls using eTDIPS (http://www.cc.nih.gov/cip/software/etdips), a 3D reconstruction and visualization software for medical images. Within eTDIPS, landmarks are located on the 3D reconstruction and simultaneously on three orthogonal planar views of the specimen. Validation of 3D data collection systems is a standard protocol in our laboratory and we have shown that accurate and precise landmark coordinate data are collected using either method (Richtsmeier et al. 1995, 2000; Valeri et al. 1998). In this study, measurement error was less than 2% of the smallest linear distance calculated between landmarks. To minimize measurement error further, landmarks were collected twice from each specimen and the average of the two data collection trials was used in analysis.

Estimating difference in shape

Landmark coordinate data recorded from adults with the Reflex microscope and from micro-CT images of P0 mice using eTDIPS were analysed using various modules of Euclidean distance matrix analysis or EDMA (Lele & Richtsmeier, 2001). EDMA provides a coordinate system-free method for statistically evaluating differences in size, shape and growth between euploid and trisomic mice. Briefly, EDMA converts 3D landmark coordinate data to a matrix of all possible linear distances between unique pairs of landmarks. Given K landmarks measured on a skull, a matrix of [K(K − N)]/2 unique linear distances can be calculated. Sample-specific averages of these linear distances are calculated and differences in 3D form are statistically evaluated as a matrix of ratios of all like linear distances in the two samples under study. The expectation under the null hypothesis of similarity in shape is a matrix of 1's. A ratio of greater or less than 1.0 for any linear distance indicates that the samples are dissimilar for that measure.

Confidence intervals were used to statistically evaluate the similarity of individual linear distances between samples, thereby localizing form difference to particular linear distances and landmarks. In our specific application, the null hypothesis of similarity between samples for each linear distance was evaluated using 100 000 bootstrapped group assignments made randomly and with replacement from the euploid sample. The null hypothesis of similarity in shape is rejected if the 90% confidence interval produced did not include 1.0 (for details see Lele & Richtsmeier, 1995; Lele & Richtsmeier, 2001).

In addition, tests for differences in global shape of anatomical regions are evaluated by a test of the null hypothesis of similarity in shape using an alternative non-parametric bootstrapping procedure (Lele & Richtsmeier, 2001). Subsets of landmarks were identified that summarize the morphology of anatomical regions (Table 1). Use of these subsets in the evaluation of global shape differences ensures that the sample size exceeds the number of landmarks considered, a prerequisite for statistical testing. Analysing each subset separately, 100 000 bootstrapped group assignments are made randomly and with replacement using the original euploid and trisomic samples. The null hypothesis of similarity in global shape for an anatomical region is rejected when P ≤ 0.05. Global differences in shape between trisomic and euploid P0 mice were statistically evaluated for seven anatomical regions: palate including premaxilla, maxilla, and pterygoid bones (landmarks 8–15); anterior face including nasal, maxillary and premaxilla bones (landmarks 1–3, 8, 9, 21, 22); anterior neurocranium including maxillary and malar bones (landmarks 2–7, 23, 24), mandible (landmarks 16–20); posterior neurocranium including the frontal, parietal, temporal and zygomatic (jugal) bones (landmarks 23–28, 38, 39); anterior cranial base including the occipital, basisphenoid, pterygoid bones (landmarks 29–31); and posterior cranial base including the four unfused portions of the occipital bone (landmarks 32–37). Differences in trisomic and euploid adult skull morphologies have previously been described using similar methods (Richtsmeier et al. 2000). The reader should note that the global difference between trisomic and euploid mice for a specific region might not reach significance in a null hypothesis test, while particular linear distances within that region might reach statistical significance by confidence intervals.

Table 1.

Results (P-values) of null hypothesis testing for form difference between trisomic and euploid P0 mice. Subsets that yield significant results (P ≤ 0.05) are marked with an asterisk. Landmarks are shown on the P0 skull in Fig. 1

| Landmark subset | Landmarks included in subset | P |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior face* | 1 2 3 8 9 21 22 | 0.039 |

| Anterior neurocranium* | 2 3 4 5 6 7 23 24 | 0.002 |

| Posterior neurocranium* | 23 24 25 26 27 28 38 39 | 0.001 |

| Palate* | 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | 0.002 |

| Anterior cranial base | 29 30 31 | 0.139 |

| Posterior cranial base | 32 33 34 35 36 37 | 0.563 |

| Mandible* | 16 17 18 19 20 | 0.002 |

Estimating difference in growth

Analysis of differences in growth required the use of a reduced set of landmarks shared between P0 and adult mice (Fig. 1, Table 2). To compare patterns of skull growth between euploid and trisomic mice, we first directly compare P0 and adult mice within each group. Growth is estimated for each sample as the relative change in the lengths of linear distances between P0 and adult mice using methods similar to those described above. Difference in growth between samples is estimated as a ratio of the defined relative growth metrics for the two samples. Relative growth estimated for each linear distance in the trisomic sample was entered in the numerator while relative growth of the corresponding linear distance in the euploid sample was the denominator. For any interlandmark distances, the further the value of any ratio is from 1, the greater the difference in growth between euploid and trisomic mice. As in the study of shape differences, two non-parametric statistical tests were used to determine whether patterns of growth differ between euploid and trisomic mice (Richtsmeier & Lele, 1993; Lele & Richtsmeier, 2001). Differences in local growth were statistically evaluated using non-parametric confidence intervals (100 000 bootstrapped steps) for specific interlandmark distances (α = 0.10). Confidence intervals that do not include 1.0 indicate that growth for that linear distance differs significantly between the two samples.

Table 2.

Results (P-values) of null-hypothesis testing for differences in growth between Ts65Dn trisomic and euploid mice for specific anatomical regions. Subsets that yield significant results (P ≤ 0.05) are marked with an asterisk. Landmark locations are depicted on P0 and on adult skulls in Fig. 1

| Landmark subset | Landmarks included in subset | P |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior face | 1 2 3 8 9 | 0.179 |

| Anterior neurocranium | 2 3 4 5 6 7 | 0.082 |

| Palate* | 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | 0.006 |

| Mandible* | 16 17 18 19 20 | 0.001 |

Growth differences for anatomical regions were estimated for a designated subset of landmarks and tested statistically against a null hypothesis of similarity in growth patterns using 100 000 bootstrapped steps and a significance level of P = 0.05. Global differences in growth between trisomic and euploid mice were statistically evaluated for four anatomical regions of the craniofacial complex (see Table 2): palate including premaxilla, maxilla, and pterygoid bones (landmarks 8–15); anterior face including nasal, maxillary and premaxilla bones (landmarks 1–3, 8, 9); anterior neurocranium including maxillary and malar bones (landmarks 2–7), and the mandible (landmarks 16–20). Detailed explanations of this approach to the comparative study of growth patterns have been previously published (Lele & Richtsmeier, 2001; Richtsmeier & Lele, 1993). EDMA software can be downloaded free from http://getahead.psu.edu.

Results

Difference in shape of Ts65Dn and euploid skulls at P0

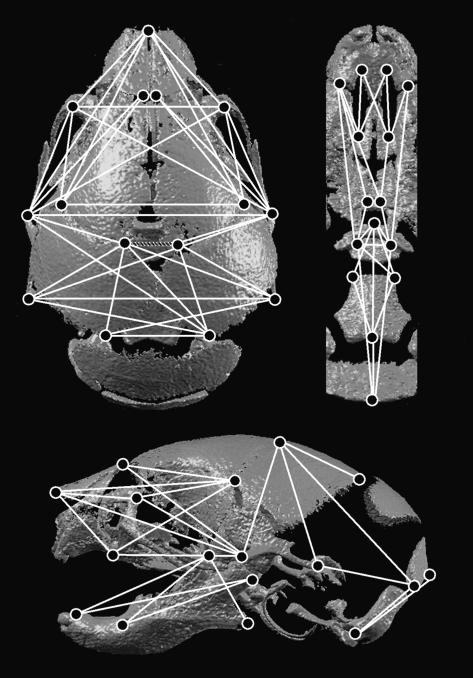

At P0, Ts65Dn trisomic mice demonstrate statistically significant differences in global shape in 5/7 anatomical subsets (Table 1). Global shape differences do not reach our chosen level of statistical significance for either the anterior or the posterior cranial base, although specific linear distances of the cranial base show significant reductions in Ts65Dn trisomic mice (Fig. 2). The patterns of shape difference between Ts65Dn and euploid mice at P0 are described by specific landmarks (lnd) and linear distances (ld) by naming the lnd that serve as endpoints of the linear distance (e.g. lnd 3 and 5 are the endpoints of ld 3-to-5). For symmetric distances on the right and left side, only one is given in the text.

Fig. 2.

Form difference analysis at P0. Linear distances among landmarks (1–39) that were shown to be significantly different between euploid and trisomic Ts65Dn mice at P0 shown on a superior (top left), inferior (top right) and lateral (bottom) view of a 3D reconstruction of an imaged P0 skull. Solid white lines indicate linear distances that are smaller in trisomic mice, while the single patterned line indicates the linear distance that is larger in trisomic mice compared with euploid littermates at P0.

Face

The anterior face is reduced in trisomic mice along the rostrocaudal (RC) axis but not along the mediolateral (ML) or dorsoventral (DV) axis. The palate is significantly reduced along the RC axis with no reductions along the ML axis. The combination of these two findings results in a shorter trisomic P0 rostrum that maintains the height and width of the normal rostrum. The P0 trisomic/euploid differences demonstrated here contrast with those found in the adult mouse in that no significant differences are found local to the posterior palate in adult Ts65Dn mice. This suggests that the palatal shelves of the palatine bones and alveolar portion of the maxillae are affected differently in trisomy than are the palatal portions of the premaxillae and maxillae.

Neurocranium

In large part, the anterior neurocranium subset reflects the shape of the frontal bones and their association with the zygomatic process of the squamosal bone. Linear distances in this subset show significant reductions along the ML and RC axes in trisomic mice but reduction along the SI axis is not indicated for the anterior neurocranium. The more anterior aspect of the neurocranium joins the face and, like the face, experiences reductions along the RC axis. The single linear distance that is larger in trisomic P0 neurocrania as compared with euploid mice measures the mediolateral diameter of a large fontanelle at the intersection of the coronal and sagittal sutures reflecting reduced ossification of the frontal and parietal bones at P0 in trisomy (ld 23-to-24).

The posterior neurocranium subset consists of landmarks located around the borders of the parietal and squasmosal bones. Whereas the posterior aspect of the neurocranium is reduced along the SI axis (lds 23-to-6, 23-to-27) and the RC axis (lds 23-to-25, 23-to-38) in P0 Ts65Dn mice, the adult Ts65Dn skull does not demonstrate significant reduction along the SI axis (Richtsmeier et al. 2000). Instead, we identify an adult trisomic posterior neurocranium that is reduced along the ML and RC axes (Richtsmeier et al. 2000). Although significant reduction in skull width is evident at P0 (lds 2-to-3, 4-to-5, 6-to-7, 27-to-28), fewer reductions along the ML axis are seen in trisomic adults which have a significantly shorter (RC) and minimally narrower (ML) neurocranium. Brachycephaly measured in adult Ts65Dn mice therefore results from an RC shortening of the neurocranium, rather than a substantial increase in width of the adult Ts65Dn skull.

Cranial base

Neither the anterior nor the posterior cranial base shows statistically significant differences in global shape between trisomic and euploid mice at P0 (Table 1), although many linear distances located within these anatomical regions show significant reductions in trisomic P0 mice (Fig. 2). Significant differences are orientated exclusively along the RC axis in the anterior cranial base, and along the RC (e.g. ld 36-to-37) and oblique DV axis (lds 34-to-37, 35-to-37) in the posterior cranial base. Differences between the P0 Ts65Dn and euploid cranial base show patterns similar to those seen in adult mice, with most differences occurring along the RC axis with little change along the ML axis.

Mandible

At P0 the trisomic mandible is reduced relative to euploid with differences affecting all landmarks. The significant differences connecting the coronoid and condylar processes (lnds 16 and 17) with landmarks situated on the body of the mandible (lnds 19 and 20) show reductions orientated along the RC axis matching the reduction in the anterior face and palate. In addition, the linear distance connecting the coronoid and angular processes (ld 16-to-18) reduces the mandible along an oblique DV axis. The condylar process is relatively less reduced in adult (Richtsmeier et al. 2000) as compared with P0 trisomic mice. While the angular process of adult trisomic mice showed many significant differences when compared with euploid littermates (Richtsmeier et al. 2000), this analysis does not reveal a comparable amount of dysmorphology local to the angular process in P0 trisomic mice.

Differences in the growth of Ts65Dn and euploid skulls

With the establishment of comparative morphology at P0, we were able to evaluate the growth in Ts65Dn mice relative to that in their euploid counterparts. Results of the test of the null hypothesis of similarity in growth for each anatomical region (Table 2) and the outcomes of the tests for localized differences in growth as established by confidence intervals are summarized here.

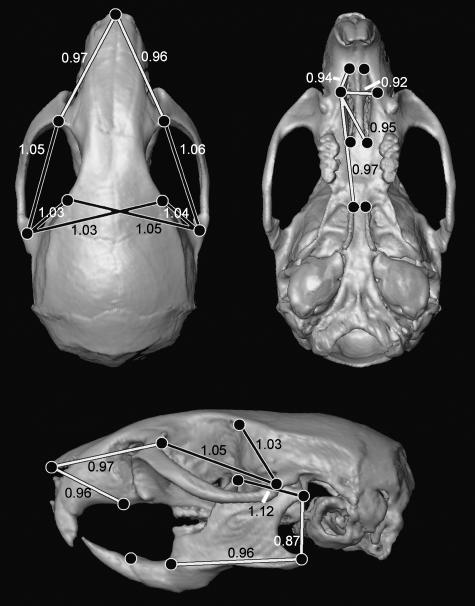

Anterior face

Global growth of the anterior snout was not significantly different between Ts65Dn and euploid mice (P = 0.179) at our chosen level of significance. However, confidence intervals (0.95 ≤ α ≤ 1.05) demonstrate significantly different growth for several individual linear distances within this subset (Fig. 3). Localized reduction in growth of the face of trisomic mice occurs along the RC axis from nasale to points on the zygomatic process of the maxilla (lds 1-to-2, 1-to-3). Linear distances representing the RC length of the premaxillae (lds 1-to-8, 1-to-9) also demonstrate significantly reduced growth in Ts65Dn mice compared with euploid littermates. Reduced magnitudes of growth coupled with premaxillae that are significantly reduced at P0 in Ts65Dn (Fig. 2) produces significantly smaller adult Ts65Dn premaxillae.

Fig. 3.

Growth difference analysis. Composite summary of growth comparisons for the face, palate and mandible of Ts65Dn and euploid mice (landmarks 1–20). Linear distances demonstrating statistically significant increased growth in the trisomic mice are indicated by black lines (outlined in white), while those linear distances in which trisomic mice demonstrated reduced growth compared with euploid littermates are indicated by white lines (outlined in black). Figures not to scale.

Anterior neurocranium

This region primarily reflects growth dynamics of the maxilla, frontal, zygomatic (jugal) and temporal bones. Global growth of this region is not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.082). However, confidence interval testing demonstrates significantly different growth between the two groups for several linear distances.

Ts65Dn mice grow significantly more than their euploid littermates along distances that reflect RC dimensions of the zygomatic arches and frontal bones (linear distances 2-to-6 and 3-to-7). The Ts65Dn mice also demonstrate a slight but significant increase in growth along distances spanning the width of the posterior portion of the frontal bones (lds 4-to-7, 5-to-6). These are the only ML vectors of growth that are statistically increased in trisomic mice as compared with euploid mice (Fig. 3) and contribute to the brachycephaly already demonstrated in adult Ts65Dn mice and DS individuals.

These localized increases in growth of the anterior portion of the neurocranium and decreases in growth of the trisomic face indicate the vectors of postnatal growth involved in the production of the statistically different morphology of Ts65Dn mice. In humans with DS, the greatest changes in growth velocity are localized to the maxillae, a finding mirrored in our analysis of Ts65Dn (e.g. Frostad et al. 1971; Fink et al. 1975). Changes in the ML growth patterns of the neurocranium contribute to brachycephaly in Ts65Dn, suggesting that a similar process may contribute to brachycephaly in individuals with DS.

Palate

The palate demonstrates statistically different global patterns of growth from P0 to adulthood in the two groups of mice (P = 0.006) as well as significantly reduced growth of specific linear distances along RC and ML dimensions of the palate (Fig. 3).

Reductions in growth along the RC axis of all bones of the murine palate (premaxillae, maxillae, palatine) contribute to the reduced dimensions of the trisomic snout (Fig. 3). One ML distance, representing the width of the maxilla (ld 8-to-9), demonstrates significantly reduced growth in width of the trisomic palate. The reduced growth of the palate contributes to an overall short snout in adult Ts65Dn mice and parallels the reduced growth of the maxilla and palate noted in DS individuals (Fischer-Brandies, 1988; Skrinjaric et al. 2004; Lauridsen et al. 2005).

Mandible

Global growth of the mandible is significantly different between Ts65Dn and euploid mice (P = 0.001) and confidence intervals indicate those individual linear distances whose growth is significantly affected in trisomy (Fig. 3). In Ts65Dn mice as in DS, the mandible is characterized by reductions in size of the bony processes: coronoid, condylar, angular (landmarks 16–18) (O’Riordan & Walker, 1978). In addition to abnormal P0 morphology, varying growth patterns contribute to the reductions in the size of the mandibular processes noted in adults. For example, the linear distance between coronoid and condylar processes (ld 16-to-17) demonstrates significantly increased growth (12%) in Ts65Dn mice, reflecting an RC expansion of the mandibular notch corresponding to a decrease in growth magnitude along those vectors that separate the tip of the coronoid process and the condyle in trisomic mice (Richtsmeier et al. 2000). Growth in RC length (ld 18-to-19) and DV height (ld 17-to-18) of the mandibular ramus indicates a reduction in size of the mandibular angle in Ts65Dn mice and contributes to the globally reduced size of the Ts65Dn mandible.

The role of size difference between groups

Comparisons of Ts65Dn mice at P0 show reduction in skull size of trisomic mice for all dimensions, but the magnitudes of the differences vary across the skull. Adult trisomic mice are smaller than euploid mice along some craniofacial dimensions but larger than euploid mice for others with differences of greatest magnitude on the face and on the cranial base (Richtsmeier et al. 2000; Leszl et al. 2006). The aneuploid mandible is consistently smaller relative to euploid in both age groups, although magnitudes of the differences are somewhat greater in adult mice. Although our results do not suggest a uniform scaling of the aneuploid mice relative to their euploid littermates, the observed size differences based on ploidy prompted an additional analysis.

We tested whether ploidy-related size differences account for the documented shape and growth differences between groups using standard methods of bivariate allometry and a principal components analysis (PCA). For the bivariate analyses, least squares regressions were conducted using the standard base-e logarithm allometry equation, ln y = a + b * ln(x), where y is a single linear dimension (we considered those that showed significant differences in growth between euploid and aneuploid mice) and x is a measure of size (we used overall cranial length measured from opisthion to nasale). Bivariate analyses substantiate what we found in our shape and growth analyses indicating strong positive ontogenetic allometry of the facial skeleton in both euploid and aneuploid mice with euploid mice tending towards larger sizes and aneuploid tending towards smaller sizes but with overlap between groups. Bivariate regressions of those measures that grow differently in euploid and aneuploid mice confirm the shape differences illustrated by EDMA. Shape differences between euploid and aneuploid are not consistently more or less prevalent at either age, indicating that shape differences are not a function of size difference. The PCA considered all linear distances (log10) calculated between facial landmarks as an overall measure of shape. When the principal component (PC) scores for the first PC are plotted against skull size (measured as log10 of cranial length), shape differences between groups identified by ploidy are not more prevalent in the older (larger) individuals. These results indicate that allometry is not a determinant of the observed shape differences between groups based on ploidy.

Discussion

Quantitative analysis of adult craniofacial phenotypes and the growth trajectories that produce them is an essential step in defining genetic influences on developmental pathways that are perturbed by genetic changes (Hallgrímsson et al. 2002, 2004; Wilkins, 2002). We have demonstrated that trisomy results in craniofacial dysmorphology at birth and in adults, and that the processes of postnatal development are affected such that craniofacial growth patterns differ between Ts65Dn and euploid mice. The features that are divergent between trisomic and euploid mice at P0 differ from those that are divergent in adults and thus differences in postnatal growth patterns of Ts65Dn mice contribute to the differences in adult craniofacial morphology just as they do in DS.

Differences in craniofacial growth patterns between trisomic and euploid mice parallel those identified in growth-related analyses of craniofacial morphology in individuals with DS. The correspondences are not absolute due in part to differences in methods of data collection and analytical procedures, but clear parallels exist. For example, relative increases in growth in trisomic mice along the ML aspect of the posterior portion of the frontal bone as well as maintenance of normal growth magnitudes in the more posterior portions of the neurocranium correspond to those involved in the production of brachycephaly, a consistent feature of DS. Landmark subsets for the face, palate and mandible indicate that growth is reduced along the RC dimension in trisomic mice, resulting in a relatively short snout. This relates to the findings of Fink et al. (1975) who found increased dysmorphology in facial length in DS with age. Palatal dimensions, reported here for the first time in a mouse model of DS, demonstrate reduced growth in several dimensions, leading to a relatively short and narrow palate. These changes correspond to alterations of the DS palate that shows deficiencies in growth along the AP axis, specifically along the maxillae (Pryor & Thelander, 1967; O’Riordan & Walker, 1978; Allanson et al. 1993). Whether narrowing of the Ts65Dn palate corresponds to the high arched palate documented in DS remains to be determined.

Factors underlying changes in growth patterns and phenotypic variation in DS include the genes at dosage imbalance, the interaction of genetic modifiers (reflecting allelic variation either on Hsa21 or on other chromosomes), variation in epigenetic conditions, and stochastic processes of development. A hypothesis that a gene or genes in a ‘critical region’ are sufficient to cause the craniofacial anomalies of DS is not supported by direct experimentation (Olson et al. 2004b). The genetic basis for the pathogenesis of most DS features remains to be elucidated and the potential genetic mechanisms are complex (Potier et al. 2006; Roper & Reeves, 2006). For example, Roper et al. (2006) used the Ts65Dn mouse to explore the role of significantly decreased numbers of granule and Purkinje cell neurons in the production of the DS phenotype of reduced cerebellar size. The authors demonstrated a substantially reduced mitogenic response to Hedgehog protein signalling in granule cell precursors in early postnatal development of Ts65Dn mice, providing an explanation for reduced cerebellar size. As sonic hedgehog is not present on Hsa21 or Mmu16, the effects are clearly secondary or tertiary to the initial effects of a trisomic gene or genes.

It has long been known that brain and skull development are tightly linked. An intimate skull–brain interaction was proposed some time ago based on functional requirements and biomechanical influences of tissue proximity (Klaauw, 1945, 1948–52; Moss, 1971), but additional potential bases for the relationships that underlie these tissues are now being offered (Hall & Miyake, 2000; Opperman, 2000; Carroll, 2001; Yu et al. 2001; Depew et al. 2002; Francis-West et al. 2003; Hall, 2003a,b; Mao et al. 2003; Ogle et al. 2004; Opperman & Rawlins, 2005; Opperman et al. 2006). A current appreciation of the link between neural and cranial tissues considers position-dependent gene expression, shared genetic pathways, interactions among cell products of various tissues, and the multiple effects of gene products and molecular signaling strategies throughout the course of development. Genes and their products must be considered as participants in developmental pathways within a framework that includes the complex dynamics of cranial construction. The role of ‘emergent’ (self-organizing) morphology is becoming increasingly evident in this system (Wilkins, 2002; Salazar-Ciudad et al. 2003; Weiss & Buchanan, 2004; Carroll, 2005; Weiss, 2005; Depew & Simpson, 2006). The spatial composition and physiological performance of cell aggregates of formative brain and skull through time embody complex developmental mechanisms.

The direct parallels of dysmorphology that we have documented between Ts65Dn skulls and the skulls of children with DS as well as parallels in aspects of brain dysmorphology are indicative of the evolutionary conservation of developmental programmes across vertebrates (Reeves et al. 2001). However, comparative analyses of craniofacial phenotypes in various mouse models for DS suggest that the genotype–phenotype relationship is more complex than originally thought. In a study of adult brain morphology in mouse models for DS, we have shown that the differences between Ts65Dn aneuploid and euploid mice differ from the euploid–trisomy differences observed in two additional DS mouse models that have fewer orthologues of human genes at dosage imbalance (Aldridge et al. 2006). Ts1Rhr mice are trisomic for genes corresponding to the so-called Down syndrome critical region (DSCR), which was purported to contain a dosage-sensitive gene or genes responsible for many craniofacial phenotypes of DS, while Ms1Rhr mice are monosomic for the same segment (Olson et al. 2004a). Ts1Rhr and Ms1Rhr mice show phenotypic effects on cerebellum, overall brain, and skull that are different from each other and from Ts65Dn (Olson et al. 2004a,b; Aldridge et al. 2006).

At conception trisomy sets a series of developmental events in motion. Potier et al. (2006) demonstrated that transcriptional signatures of gene expression patterns in cerebellum of DS mouse models are not constant but change through early postnatal development. This shifting nature of gene dysregulation in trisomy surely occurs throughout prenatal development as well. Moreover, the developmental patterns set in motion by trisomy result in immediate changes in morphology. Morphology emerges from communication between cell populations whose gene products influence the next morphogenetic step. The production of dysmorphic features feeds into changes in development in a very real way as properties of emergent phenotypes contribute to patterns and processes of development. The diverse DS mouse models enable comparative studies of the architecture of genotype–phenotype maps, providing effective tools for sorting through the phenotypic consequences of various trisomies and the interaction of gene expression patterns, gene networks, developmental pathways and developing morphologies at any point in development.

In this study, we have demonstrated parallels of growth between Ts65Dn mice and humans with DS. That correspondences in the behaviour of orthologous genes and their networks exist across species appears to be the rule rather than the exception. Rules that govern the interaction of emergent structure and the dynamics generated by the physics of changing morphologies may also be conserved within the parameters that differentiate vertebrate species (e.g. morphological and gene sequence divergence of human and mouse). Mouse models for DS provide the means by which we may understand how particular gene products and their networks affect the dynamics of the morphogenetic processes in which they participate and precisely how aneuploidy changes gene products, essentially altering emergent structure and its signalling capacity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Timothy Ryan for his excellent technical support in the acquisition of the microcomputed tomographic images, Jennifer Leszl for help with data collection and Katherine Willmore for her critical discussion. EDMA software can be downloaded free from http://getahead.psu.edu. This work was supported in part by PHS award HD038384 (R.H.R.).

References

- Aldridge K, Reeves R, Baxter LL, Olson LE, Richtsmeier JT. Differential effects of trisomy on brain shape and Volume in related aneuploid mouse models. Am J Med Genet. 2006;9999(Part A):1–11. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allanson J, O’Hara P, Farkas L, Nair R. Anthropometric craniofacial pattern profiles in Down syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1993;47:748–752. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320470530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonarakis SE, Lyle R, Dermitzakis ET, Reymond A, Deutsch S. Chromosome 21 and down syndrome: from genomics to pathophysiology. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:725–738. doi: 10.1038/nrg1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchley W, Hall B. A model for development and evolution of complex morphological structures. Biol Rev. 1991;66:101–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185x.1991.tb01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagic I, Verzak Z. Craniofacial anthropometric analysis in Down syndrome patients. Coll Antropol. 2003;27(Suppl. 2):23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter L, Abrams M, Richtsmeier J, Reiss A, Reeves R. Ts65Dn segmentally trisomic mice exhibit morphological changes in cerebellum similar to those in Down Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:A159. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter LL, Moran TH, Richtsmeier JT, Troncoso J, Reeves RH. Discovery and genetic localization of Down syndrome cerebellar phenotypes using the Ts65Dn mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:195–202. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll S. From DNA to Diversity: Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design. Oxford: Blackwell; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll SB. Evolution at two levels: on genes and form. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JD, Salehi A, Delcroix JD, et al. Failed retrograde transport of NGF in a mouse model of Down syndrome: reversal of cholinergic neurodegenerative phenotypes following NGF infusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10439–10444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181219298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronk C, Reed R. Canalization of growth in Down syndrome children three months to six years. Human Biol. 1981;53:383–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davisson M, Schmidt C, Reeves N, et al. Segmental trisomy as a mouse model for Down Syndrome. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1993;384:117–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depew MJ, Tucker AS, Sharpe PT. Craniofacial development. In: Rossant J, Tam PPL, editors. Mouse Development: Patterning, Morphogensis, and Organogenesis. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 421–498. [Google Scholar]

- Depew MJ, Simpson CA. 21st century neontology and the comparative development of the vertebrate skull. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1256–1291. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escorihuela R, Fernandez-Teruel A, Vallina I, et al. A behavioral assessment of Ts65Dn mice: a putative Down syndrome model. Neurosci Lett. 1995;199:143–146. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink G, Madaus W, Walker G. A quantitative study of the face in Down syndrome. Am J Orthod. 1975;67:540–553. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(75)90299-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Brandies H. Cephalometric comparison between children with and without Down syndrome. Eur J Orthod. 1988;10:255–263. doi: 10.1093/ejo/10.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis-West PH, Robson L, Evans DJR. Craniofacial Development: the Tissue and Molecular Interactions That Control Development of the Head. Berlin: Springer; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frostad W, Cleall J, Melosky L. Craniofacial complex in the Trisomy 21 syndrome (Down syndrome) Arch Oral Biol. 1971;16:707–722. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(71)90116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BK, Miyake T. All for one and one for all: condensations and the initiation of skeletal development. Bioessays. 2000;22:138–147. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200002)22:2<138::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall B. Unlocking the black box between genotype and phenotype: cell condensations as morphogenetic (modular) units. Biol Philosophy. 2003a;18:219–247. [Google Scholar]

- Hall BK. The emergence of form: The shape of things to come. Dev Dyn. 2003b;228:292–298. [Google Scholar]

- Hallgrímsson B, Willmore K, Hall BK. Canalization, developmental stability, and morphological integration in primate limbs. Yearb Phys Anthropol. 2002;45:131–158. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgrímsson B, Willmore K, Dorval C, Cooper DM. Craniofacial variability and modularity in macaques and mice. J Exp Zool Part B Mol Dev Evol. 2004;302:207–225. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman DM, Santucci D, Kilbridge J, et al. Developmental abnormalities and age-related neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13333–13338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde LA, Crnic LS, Pollock A, Bickford PC. Motor learning in Ts65Dn mice, a model for Down syndrome. Dev Psychobiol. 2001;38:33–45. doi: 10.1002/1098-2302(2001)38:1<33::aid-dev3>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisling E. Cranial Morphology in Down Syndrome: a Comparative Roentgencephalometric Study in Adult Males. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Klaauw CVD. Cerebral skull and facial skull. Arch Neerl Zool. 1945;7:16–37. [Google Scholar]

- Klaauw C. Size and position of the functional components of the skull. Arch Neerl Zool. 1948–52;7:16–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lauridsen H, Hansen BF, Reintoft I, Keeling JW, Skovgaard LT, Kjaer I. Short hard palate in prenatal trisomy 21. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2005;8:91–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2005.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lele S, Richtsmeier JT. Euclidean distance matrix analysis: confidence intervals for form and growth differences. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1995;98:73–86. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330980107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lele S, Richtsmeier J. An Invariant Approach to the Statistical Analysis of Shapes. London: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mao JJ, Wang X, Mooney MP, Kopher RA, Nudera JA. Strain induced osteogenesis of the craniofacial suture upon controlled delivery of low-frequency cyclic forces. Front Biosci. 2003;8:a10–7. doi: 10.2741/917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C, Lee J, Birren B, Stetten G, Baxter L, Reeves R. Integration of cytogenetic with recombinational and physical maps of mouse chormosome 16. Genomics. 1999;59:1–5. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss M. Functional Cranial Analysis and the Functional Matrix. Patterns of Orofacial Growth and Development. Ann Arbor: American Speech and Hearing Association Reports; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Myrelid A, Gustafsson J, Ollars B, Anneren G. Growth charts for Down syndrome from birth to 18 years of age. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87:97–103. doi: 10.1136/adc.87.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Riordan M, Walker G. Dimensional and proportional characteristics of the face in Down syndrome. J Dentistry Handicapped. 1978;4:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle RC, Tholpady SS, McGlynn KA, Ogle RA. Regulation of cranial suture morphogenesis. Cells Tissues Organs. 2004;176:54–66. doi: 10.1159/000075027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson L, Richtsmeier JT, Leszl J, Reeves R. A chromosome 21 critical region does not cause specific Down syndrome phenotypes. Science. 2004a;306:687–690. doi: 10.1126/science.1098992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson LE, Roper RJ, Baxter LL, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Reeves RH. Down syndrome mouse models Ts65Dn, Ts1Cje, and Ms1Cje/Ts65Dn exhibit variable severity of cerebellar phenotypes. Dev Dyn. 2004b;230:581–589. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperman LA. Cranial sutures as intramembranous bone growth sites. Dev Dyn. 2000;219:472–485. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1073>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperman LA, Rawlins JT. The extracellular matrix environment in suture morphogenesis and growth. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;181:127–135. doi: 10.1159/000091374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperman LA, Fernandez CR, So S, Rawlins JT. Erk1/2 signaling is required for Tgf-beta2-induced suture closure. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1292–1299. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potier MC, Rivals I, Mercier G, et al. Transcriptional disruptions in Down syndrome: a case study in the Ts1Cje mouse cerebellum during post-natal development. J Neurochem. 2006;97(Suppl. 1):104–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryor H, Thelander H. Growth deviations in handicapped children. Clin Pediatrics. 1967;6:501–512. doi: 10.1177/000992286700600819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rarick G, Wainer H, Thissen D, Seefeldt V. A double logistic comparison of growth patterns of normal children and children with Down syndrome. Ann Human Biol. 1975;2:339–346. doi: 10.1080/03014467500000951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves R, Irving N, Moran T, et al. A mouse model for Down syndrome exhibits learning and behavior deficits. Nat Genet. 1995;11:177–184. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves R, Rue E, Yu J, Kao F-T. Stch maps to mouse Chromosome 16 extending the conserved synteny with human Chromosome 21. Genomics. 1998;49:156–157. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves RH, Baxter LL, Richtsmeier JT. Too much of a good thing: mechanisms of gene action in Down syndrome. Trends Genet. 2001;17:83–88. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richtsmeier JT, Lele S. A coordinate-free approach to the analysis of growth patterns: models and theoretical considerations. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 1993;68:381–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185x.1993.tb00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richtsmeier JT, Paik CH, Elfert PC, Cole TM, Dahlman HR. Precision, repeatability, and validation of the localization of cranial landmarks using computed tomography scans. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1995;32:217–227. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1995_032_0217_pravot_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richtsmeier JT, Baxter LL, Reeves RH. Parallels of craniofacial maldevelopment in Down syndrome and Ts65Dn mice. Dev Dyn. 2000;217:137–145. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200002)217:2<137::AID-DVDY1>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper RJ, Reeves RH. Understanding the basis for Down syndrome phenotypes. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e50. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper RJ, St John HK, Philip J, Lawler A, Reeves RH. Perinatal loss of Ts65Dn Down syndrome mice. Genetics. 2006;172:437–443. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.050898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Ciudad I, Jernvall J, Newman SA. Mechanisms of pattern formation in development and evolution. Development. 2003;130:2027–2037. doi: 10.1242/dev.00425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrinjaric T, Glavina D, Jukic J. Palatal and dental arch morphology in Down syndrome. Coll Antropol. 2004;28:841–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valeri CJ, Cole TM, 3rd Lele S, Richtsmeier JT. Capturing data from three-dimensional surfaces using fuzzy landmarks. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1998;107:113–124. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199809)107:1<113::AID-AJPA9>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss K, Buchanan A. Genetics and the Logic of Evolution. New York: John Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss KM. The phenogenetic logic of life. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:36–45. doi: 10.1038/nrg1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins A. The Evolution of Developmental Pathways. Sunderland, MA: Sinaer Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yu JC, Lucas JH, Fryberg K, Borke JL. Extrinsic tension results in FGF-2 release, membrane permeability change, and intracellular Ca++ increase in immature cranial sutures. J Craniofac Surg. 2001;12:391–398. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200107000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]