Abstract

The process of eye migration in bilaterally symmetrical flatfish larvae starts with asymmetrical growth of the dorsomedial parts of the ethmoid plate together with the frontal bones, structures initially found in a symmetrical position between the eyes. The movement of these structures in the future ocular direction exerts a stretch on the fibroblasts in the connective tissue found between the moving structures and the eye that is to migrate. Secondarily, a dense cell population of fibroblasts ventral to the eye starts to proliferate, possibly cued by the pulling forces exerted by the eye. The increased growth ventral to the eye pushes the eye dorsally. Osteoblasts are deposited in the dense cell layer, forming the dermal part of the lateral ethmoid, and at full eye migration this will cover the area vacated by the migrated eye. When the migrating eye catches up with the previous migrated dermal bones, the frontals, these bones will be remodelled to accommodate the eye. Our findings suggest that a combination of extremely localized signals and more distant factors may impinge upon the outcome of the tissue remodelling. Early normal asymmetry of signalling factors may cascade on a series of events.

Keywords: biological asymmetry, bone remodelling, eye migration, flat fish, metamorphosis, osteoclastic activity

Introduction

The most spectacular post-embryonic tissue remodelling in the vertebrates is eye migration in flatfish. During their pelagic larval life, flatfish are symmetrical with one eye on each side of the head. To accommodate a benthic lifestyle, one eye relocates to the opposite side of the head during metamorphosis. Meckel (1822) was the first to recognize homologies of the cranial bones in cod and flatfish and the first to propose that the eye migration was ‘driven’ by a twisting process.

In Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus L.) larval development, the first structures to display differentiated growth are the dorsomedial parts of the ethmoid plate (Lamina precerebralis) (Sæle et al. in press), and they are therefore candidates for the driving force in the twisting process. The next structures to display asymmetric growth related to eye migration are the frontal processes (Sæle et al. in press), which are found superficially between the eyes and undergo a dramatic remodelling (Brewster, 1987; Wagemans et al. 1998; Okada et al. 2001, 2003b; Wagemans & Vandewalle, 2001; Sæle et al. 2003, in press). Given that some of these bone changes take place post-mineralization in Atlantic halibut (Sæle et al. 2003, in press), it is highly likely that osteoclastic reabsorption plays a role in eye migration.

Like most teleost species, Atlantic halibut have bones without osteocytes, termed acellular bone. In addition to the absence of osteocytes, acellular bone has smaller calcified crystals and a greater amount of organic substance, presumably collagen (Moss, 1961; Meunier & Huysseune, 1992). Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) and cathepsin K (CATK) are the main lytic enzymes that resolve minerals in bone. The osteoclast forms a sealed compartment between itself and the bone surface and the lytic enzymes are activated by the excretion of protons to the compartment. Both mono- and multinucleated osteoclasts in teleosts have been shown to function in this same way (Persson et al. 1995, 1998, 1999; Witten et al. 1999, 2000, 2001).

Remodelling of bone by osteoclastic activity is not only common in teleost fish but is also necessary for growth (Witten & Villwock, 1997a,b; Witten et al. 2000, 2001). Much attention has been given to the bones of the suspensorium, but little research has been done on the dermal neurocranial bones. We examined osteoclastic activity in the frontal processes of Atlantic halibut larvae from prior to eye migration to completion of eye migration, or stages 7 (Sæle et al. 2004) and later. Normal (n = 15) fish were compared with those exhibiting arrested eye migration (n = 9), a common affliction.

Materials and methods

Brood stock, eggs and larvae

The halibut broodstock originated from Fiskey ehf. Hjalteyri, 601 Akureyri (Iceland) (Bjornsson et al. 1998). Eggs were fertilized and incubated as described by Mangor-Jensen et al. (1998). At 73 degree-days (degrees Celcius multiplied by days) the eggs were transferred from the incubators to silos. During the yolk-sac stage the larvae were reared at 5.2 °C, as described by Harboe et al. (1994). Larvae were transferred to 3500-L, round, first-feeding tanks at 260 degree-days (50 days post-hatching) as described by Mangor-Jensen et al. (1998). The larvae were fed enriched Artemia (RH cysts, Artemia Systems, Ghent, Belgium). The temperature in the feeding tanks was kept at 10–11 °C and the fish were exposed to continuous light.

Sampling and analyses

Twenty-four fish larvae were analysed, representing stages 7, 8, 9 and juvenile fish (Sæle et al. 2004), and comprising five normal larvae at stages 7 and 8, five normal and four abnormal larvae at stage 9, and five normal and five abnormal juveniles (Sæle et al. 2004). Eye migration usually takes place during stages 8 and 9, but eye index is not synonymous with stage. Live larvae and a standard measure were individually photographed (Olympus Camedia C-5050 Zoom) and larvae anaesthetized (overdose of metacain, Argent Laboratories) prior to fixation in 10% paraformaldehyde in 50 mmol Tris, pH 7.2, for 15 min. Samples were rinsed for 60 min in tap water prior to 48 h decalcification in 10% EDTA in 100 mmol Tris buffer, pH 7.2. Samples were then dehydrated in a graded series of acetone (70, 80, 90 and 100%) before embedding in glycol-metacrylate (Technovit 8100). Procedures from fixation until embedding took place at 4 °C. Serial 5-µm-thick transverse sections were cut in the eye region, using a Leica RM 2065 microtome and sections mounted on slides (SuperFrost®Plus, Menzel-Glaser). Every fourth section was stained with borax-buffered toluidine blue and neighbouring sections stained for TRAP activity according to Witten & Villwock (1997a). TRAP-stained sections were pre-incubated for 30 min at room temperature in 0.1 m acetate buffer (pH 5.5) containing 50 mm di-sodium tartrate dehydrate. They were further incubated for 2 h at room temperature with the substrate napthol AS-TR phosphate (0.07 mg mL−1) and hexazotized pararosaniline (PRS, 0.444 mg mL−1) as an azo-coupling dye. Controls were either (i) incubated without substrate or (ii) heated at 90 °C for 15 min prior to incubation. Slides were counterstained with Gill's haematoxylin.

TRAP activity in the ocular and abocular frontal processes was measured as stained area (mm2), using computer-aided stereology (CAST 2 Olympus Denmark A/S 2000). The total number of sections examined varied from 40 in stage 8 larvae to 78 in the largest juvenile. The frontal processes were regionalized into equal thirds representing the anterior, midregion and posterior regions of the processes. No distinction was made between intra- and extracellular staining. Scores from each section were summed per individual. Double staining for cartilage and bone was done on larvae stages 7, 8, and 9. Staining procedures followed Potthoff (1984).

Immunocytochemistry

Paraffin sections, 9 µm thick, were deparaffinized in xylene (2× 10 min) and rehydrated in ethanol (2× absolute, 96, 80, 70 and 50%) for 5 min at each step. Sections were then heated 3× 5 min in 0.01 m citrate buffer, pH 6.0, at 650 W in a microwave oven and cooled to room temperature. The slides were subsequently incubated in 0.1 m phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, for 10 min followed by 30 min of incubation with 3% H2O2 to remove endogenous peroxidase activity and then rinsed 2× 5 min in PBS. The sections were then rinsed in PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100 (PBS-Tx) for 2× 10 min. Primary antibody [Monoclonal mouse Anti-Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (anti-PCNA), Dako, Glostrup, Denmark] was diluted 1 : 500 in PBS-Tx with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and incubated at room temperature overnight. Slides were rinsed 2× 10 min in PBS-Tx. Secondary antibody, rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Dako) diluted 1 : 50 in PBS-Tx-BSA was applied for 30 min, rinsed 2× 10 min each in PBS-Tx followed by incubation with mouse PAP complex (Dako) diluted 1 : 50 in PBS-Tx-BSA for 30 min and rinsed for 10 min in PBS-TX and 10 min in 0.05 m Tris/HCl, pH 7.6. The sections were then reacted in 0.05 m Tris/HCl, pH 7.6, with 0.05% 3.3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and 0.015% H2O2 for 15 min. After 2× 5-min washes in 0.05 m Tris/HCl, pH 7.6, sections were dehydrated to 80% ethanol, counterstained in eosin (0.25% eosin Y, 0.5% glacial acetic acid in 80% ethanol) and mounted in PDX (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland).

Angles

The UTHSCSA ImageTool (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX, USA) was used to measure the eye migration angle on a section of the midregion of the lens. The continuous measure of eye migration was expressed by the angle between the base of the neurocranium and the medial edge of the prospective migrating eye.

Statistical analyses

Potential differences were tested with anova or ancova. Newman–Keuls post-hoc test was used to test for significant differences between group means in an analysis of variance. Differences and effects were considered significant at P < 0.05 for all tests. anovas and post-hoc analyses were performed on Statistica 6.1 (StatSoft Inc.).

Results

The growth of frontal processes and lamina precerebralis during eye migration

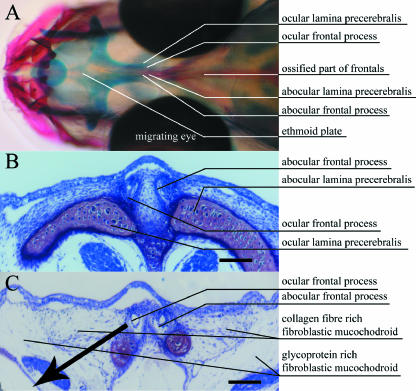

At stage 7 the frontals start to ossify in the region between the eyes (Fig. 1A). This process coincides with the primordia of the frontal processes reaching the dorso-medial parts of the ethmoid plate (lamina precerebralis), which at this point is a symmetrical structure (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Stage 7, symmetrical larvae. (A) Dorsal view of head double stained for bone (alizarin red) and cartilage (alcian blue). Calcified bone is red and cartilage is blue. (B) Cross-section anterior to eyes (hyaline ethmoid cartilage: pink). (C) Cross-section anterior region of eyes. B and C show sections 5 µm thick, stained with toluidine blue. Scale bar = 100 µm.

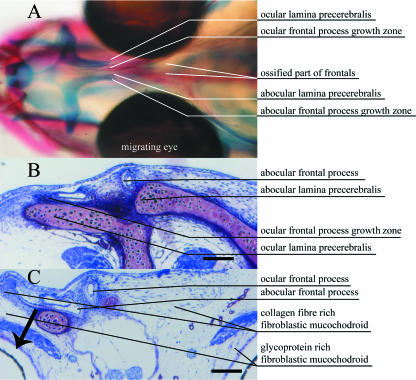

During normal asymmetric development, about stage 8, the lamina precerebralis starts to grow towards the future ocular side (usually the dextral side), expanding in parallel with its frontal process (Figs 2 and 3). On the future abocular side (usually sinistral), this frontal process is bordered laterally by the lamina precerebralis cartilage. The movement of the lamina precerebralis cartilage toward the dextral side follows the primordia of the frontal processes (Fig. 2), and later the ossified processes (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Stage 8, eye index 0. (A) Dorsal view of head double stained for bone (alizarin red) and cartilage (alcian blue). Calcified bone is red and cartilage is blue. (B) Cross-section anterior to eyes (hyaline ethmoid cartilage: pink). (C) Cross-section anterior region of eyes. B and C show sections 5 µm thick, stained with toluidine blue. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Fig. 3.

Early stage 9, eye index 2. (A) Dorsal view of head double stained for bone (alizarin red) and cartilage (alcian blue). Calcified bone is red and cartilage is blue. (B) Cross-section anterior to eyes (hyaline ethmoid cartilage: pink). (C) Cross-section anterior region of eyes. B and C show sections 5 µm thick, stained with toluidine blue. Scale bar = 100 µm.

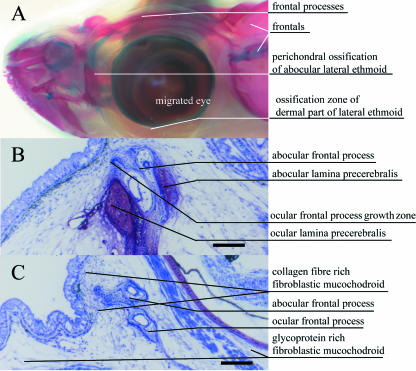

At stage 9 the frontal processes are situated on the dextral or ‘ocular’ side of the head (black arrow, Figs 1C–3C). During this migration the future ocular process has become larger than its counterpart (Figs 2 and 3), but at full eye migration they have the same size again (Fig. 4). At the end of stage 9 most of the cartilage has ossified (Fig. 4). The direction of cartilage growth is visualized by the distribution of cells staining for PCNA (black arrow in Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Late stage 9, eye index 4. (A) Dorsal view of head double stained for bone (alizarin red) and cartilage (alcian blue). Calcified bone is red and cartilage is blue. (B) Cross-section anterior to eyes (hyaline ethmoid cartilage: pink). (C) Cross-section anterior region of eyes. B and C show sections 5 µm thick, stained with toluidine blue. Scale bar = 100 µm.

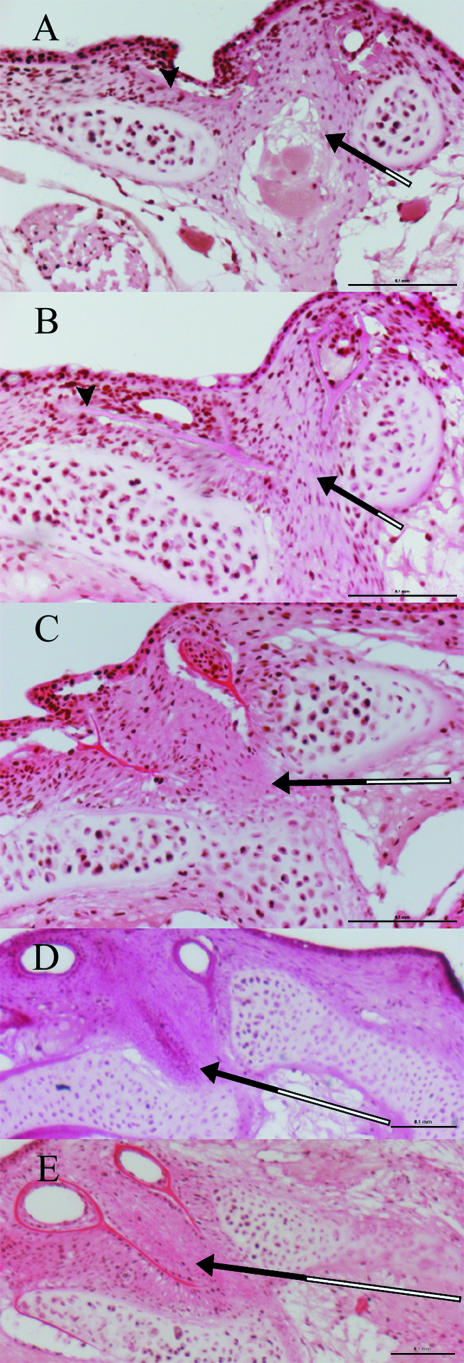

Fig. 5.

Cross-sections of the posterior border of the eyes. (A) Stage 7, eye index 0; (B) stage 7, eye index 0; (C) stage 8, eye index 1; (D) stage 9, eye index 2; (E) stage 9, eye index 3. Black arrows show the zone of proliferating cells on the abocular side of the dorsomedial part of the ethmoid cartilage. White part of arrow indicates inactive part of cartilage with no cell proliferation. Black arrowhead in A and B shows the ocular frontal process that grows parallel to the cartilage situated dorsally to it. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Changes in connective tissue and cell proliferation during eye migration

At stage 7, prior to asymmetric growth, a collagen fibre-rich fibroblastic mucochondroid (Benjamin, 1988) forms a triangle laterally on each side of the lamina precerebralis and frontal processes (Fig. 1). There is a distinct perimeter lateral to this tissue region, where the fibroblastic mucochondroid has few fibres and few fibroblasts and where most of the space is occupied by glycoproteins (Figs 1–4 and 6C).

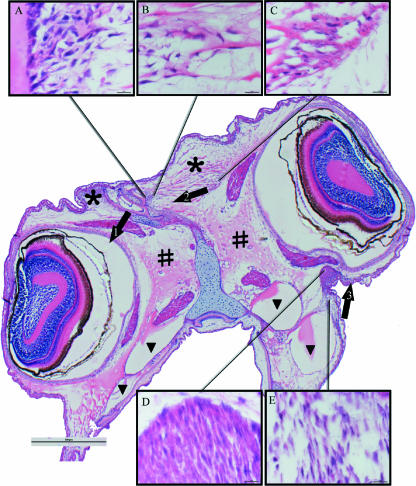

Fig. 6.

Cross-sections of the anterior region of the eyes. Stage 9 (myotome height 7.2 mm), eye index 2. Low-power micrograph: scale bar = 500 µm; higher-power micrographs A–E: scale bar = 1 µm. Growth of the dorsomedial part of the ethmoid cartilage moving towards the ocular-side eye (arrow 1). Eye moves closer to the retroorbital vesicle (black triangle), which has a laterally compressed shape. At the same time the collagen fibre-rich fibroblastic mucochondroid is stretched (arrow 2). The dense subdermal fibroblastic layer proliferates, and grows towards the dorsal margin (arrow 3). Asterisk, collagen fibre-rich fibroblastic mucochondroid; #, glycoprotein-rich fibroblastic mucochondroid.

When the lamina precerebralis and frontal processes migrate (late stage 7 to early stage 8), the fibre-rich fibroblastic mucochondroid on the sinistral or ‘abocular’ side is elongated or stretched (visualized by the orientation of the collagen fibres and the fibroblasts, see asterisk in Fig. 6) and the shape of the fibroblasts changes from denditric to elongate (Fig. 6A–C). The glycoprotein-dominated fibroblastic mucochondroid closer to the eye remains unchanged during the migration of the frontal process (Fig. 6). The fibre-rich fibroblastic mucochondroid on the dextral or ‘ocular’ side is compressed, as visualized by the dense gathering of fibroblasts lateral to the growth sectors of the dextral or ‘ocular’ frontal process (Figs 1–4 and 6). When the frontal processes have fully migrated, the retrorbital vesicles of the future ocular side are smaller in cross-section (Fig. 6) while their abocular-side counterparts are larger and almost round (Fig. 6).

The tissue ventral to the non-migrating eye contains a very low density of fibroblasts (Fig. 6). Migration of the frontal processes, illustrated in Figs 1–3, gives way to the migrating eye. The fibre-rich fibroblastic mucochondroid to where the eye will migrate does not have a high cell density (Figs 3 and 6). After eye migration has started, there is an increased subdermal and dermal cell condensation ventral to the eye (Fig. 3D,E). Fibroblasts in this cell condensation become elongated as eye migration proceeds (Fig. 3D,E).

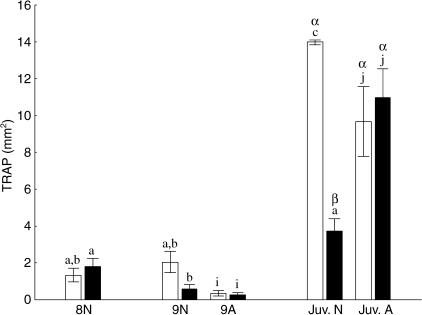

Total TRAP activity

In normal halibut there is a significant decrease in TRAP activity from stage 8 to stage 9 in the ocular frontal process, but not in the abocular frontal process (Fig. 7, P < 0.05 anova). Normally, there is an almost four-fold increase in TRAP activity in the abocular frontal process from stage 9 to the juvenile stage (Fig. 7, P < 0.005 anova). Osteoclastic activity in the ocular frontal process from stage 9 to the juvenile stage increases as well, but the increase is more modest than that of the abocular frontal process (Fig. 7, P < 0.05 anova).

Fig. 7.

Mean ± SE TRAP activity in stage 8 normal, stage 9 and juvenile (Juv.) normal (N) and abnormal (A) larvae. Black column = ocular frontal process, white column = abocular frontal process (n = 24). TRAP activity is expressed as stained area as measured by stereology. Different letters above columns denote significant differences (P < 0.05); lower-case letters indicate differences within normal (a–c) or abnormal (i–j) fish. Upper-case letters indicate differences between normal and abnormal juveniles.

Abnormal stage 9 larvae display lower TRAP activity in both frontal processes than do normal stage 8 larvae (Fig. 7, P < 0.05 anova). However, metamorphosing halibut larvae with arrested eye migration show a significant increase in TRAP activity from stage 9 to juvenile, and expression is not different between the sinistral and dextral frontal processes. Abnormal juvenile halibut have the same TRAP expression in both processes as that of the abocular frontal process in normal juveniles, but a higher expression than in the normal ocular frontal process (Fig. 7, P < 0.05 anova).

Normal fish exhibit a high correlation between eye migration and osteoclastic activity in the frontal processes, r2 = 0.81 for the abocular and r2 = 0.52 for the ocular frontal process. The abocular frontal process displays significantly higher TRAP activity than the ocular frontal process (P < 0.005 ancova). Abnormal fish that by definition lack eye migration show poor correlations: r2 = 0.34 for the abocular and r2 = 0.36 for the ocular frontal process. There is no difference between the two bone processes (P > 0.05 ancova).

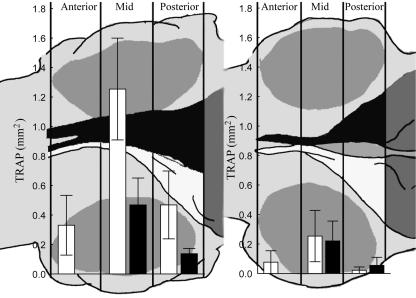

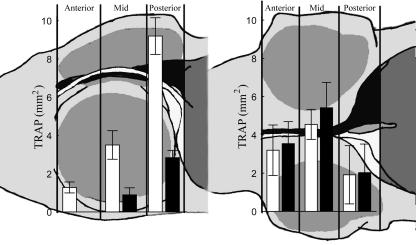

Regional TRAP activity

In normal halibut at stage 8, the TRAP expression is evenly expressed in the anterior, middle and posterior regions of the frontal processes. At stage 9 the abocular frontal process mid-region activity increases (Fig. 8, P < 0.05 anova). The abocular process of juvenile fish exhibits an anterior–posterior order of increased TRAP expression compared with earlier stages. TRAP expression in the ocular frontal process increases only in the posterior region (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Mean ± SE area of TRAP activity as measured by stereology in stage 9 normal (left) and abnormal larvae (right). Black column = ocular-side frontal process, white column = abocular-side frontal process (n = 9).

In arrested halibut lacking eye migration, TRAP expression is even and constant between the regions both in stage 9 and in the juvenile stage. There is a large increase in activity from stage 9 to the juvenile, but TRAP expression in the arrested juveniles is highly variable (Figs 8 and 9).

Fig. 9.

Mean ± SE area of TRAP activity as measured by stereology in juvenile normal (left) and abnormal fish (right). Black column = ocular-side frontal process, white column = abocular-side frontal process (n = 10).

At stage 9 in the anterior regions of the frontal processes, there is no difference in TRAP expression between arrested and normal fish. However, in normal stage 9 halibut, the mid-region of the abocular frontal process has significantly higher TRAP expression than in the ocular frontal process and than found in both frontal processes of arrested fish (Fig. 8, P < 0.05 anova). In the normal posterior region, there is no difference in TRAP activity between the abocular and ocular frontal processes, but in arrested halibut there is only activity in the ocular process (Fig. 8, P < 0.05 anova).

In normal juvenile halibut TRAP expression in the abocular frontal process increases significantly in the anterior–posterior direction (Fig. 9, P < 0.05 anova). The ocular frontal process expresses low TRAP activity in the mid- and posterior regions, and no TRAP activity could be detected in the anterior region. By contrast, arrested juvenile halibut displayed a stable TRAP expression in all three regions, and activity did not differ between either frontal process (Fig. 9, P > 0.05 anova).

Discussion

In determining the steps involved in developing cranial asymmetry in flatfish, it seems a combination of extremely localized signals and more distant factors may impinge upon the outcome of the tissue remodelling. Early normal asymmetry of signalling factors may cascade on a series of events.

Flatfish cranial bone remodelling

The asymmetric growth of the lamina precerebralis is one of the first morphological signs of halibut eye migration (Sæle et al. in press). Observations of larvae at initial eye migration bear witness to its driving role in the process: the abocular side lamina precerebralis pushes the partly calcified frontal processes in the future ocular direction. Parts of the frontal bones calcify prior to and during this remodelling, as is the case for turbot and Japanese flounder (Wagemans et al. 1998; Okada et al. 2001). The direction of growth of the cartilage is expressed by the presence of isogenous groups of chondrocytes, indicating cell division, as well as by immunohistochemical staining of PCNA.

Concurrent with the asymmetric growth of the lamina precerebralis, the ocular-side frontal process grows at its lateral margin, as indicated by high levels of osteoblastic cell proliferation. Schematic characterization by Wagemans et al. (1998) does not indicate a similar growth pattern of the ethmoid plate and lamina precerebralis in turbot, nor does there seem to be a connection between the frontal processes and the lamina precerebralis. Brewster (1987) proposes an ethmoid/frontal process connection at peak metamorphosis in common sole (Solea solea), but it is unclear when this occurs. According to Wagemans & Vandewalle (2001) the frontal primordia are present in the symmetric common sole larvae at 12 days post-hatching, but do not calcify until day 26 post-hatch, when the eyes are fully migrated. The frontal processes are not mentioned until post-metamorphosis when they are fully ossified and in contact with the lateral ethmoids in sole. Based on Brewster's (1987) schematic drawings and descriptions dab (Pleuronectes limanda) has a premetamorphic asymmetry of the ethmoid plate and an early connection with the frontal processes. In topknot (Zeugopterus punctatus) there is a premetamorphic connection between the lamina precerebralis and the frontal processes. Brewster (1987) also reports the Z. punctatus frontals to be partly ossified prior to complete metamorphosis as is the case for Eckstrom's topknot (Phrynorhhombus regius). Thus, most of the cranial element changes seem to be conserved across species during flatfish metamorphosis and as such may be vulnerable to the same cascade of early signals causing abnormalities.

Soft tissue remodelling

The displacement and growth of the frontal processes are likely to result in pressure in the ventral direction on the future ocular side eye (arrow 1 in Fig. 6). This movement of the eye is visualized by the compression of the retrorbital vesicles of the future ocular side (Fig. 6).

The fibre-rich fibroblastic mucochondroid is stretched between the abocular frontal process and the glycoprotein-rich fibroblastic mucochondroid close to the sinistral eye. The difference in fibre content and the well-defined shift between the tissue types imply a functional cause. Fibroblasts change shape in stretched tissue from a dendritic form to a more sheet-like form (Neidlinger-Wilke et al. 2002; Langevin et al. 2005), as seen first in the fibroblasts dorsomedial to the migrating eye and second in the subdermal layer ventral to the migrating eye, as described by Okada et al. (2001, 2003a) and Sæle et al. (in press). It has also been demonstrated that fibroblasts may increase production of collagen in response to stretch (Kim et al. 2002). It can therefore be suggested that the elastic fibres stretched out by the ‘lamina precerebralis–frontal process complex’ exert a force on the prospective migrating eye, and as such could represent the first migration signal on the eye. The secondary effect may be part of the signal increasing tissue volume ventral to the migrating eye. As this ventral cell condensation increase is in the dorsal direction it may be pushing the eye towards the dorsal margin (arrow 3 in Fig. 6).

Osteoclastic action

Resorption of bone is required for normal development in teleost fishes (Witten & Villwock, 1997a,b; Witten et al. 2000, 2001), but the pattern of osteoclastic activity is also essential for normal development. This paper shows osteoclastic remodelling of the frontal processes to accommodate the migrated eye at about stage 9, and therefore it indicates that this activity is a result of eye migration rather than a driving force, in contrast to previous proposals (Sæle et al. 2003).

The frontal processes are also remodelled in arrested juveniles, but in these fish the distribution pattern of TRAP activity is symmetrical (the same in the two frontal processes) and nearly homogeneous along the anterior–posterior axis. By contrast, bone resorption in normal fish is differentiated in the anterior–posterior direction with TRAP activity highest in the mid-region in stage 9 and in the posterior region of the frontals in juvenile halibut, and with lateral differences between the frontal processes.

Localized signals

Chondrocytes display highly flexible life cycles of proliferation, differentiation, maturation and apoptosis (Iwamoto et al. 1994, 2003; Hagiwara et al. 1996; Shum & Nuckolls, 2002; Yan et al. 2002, 2005; Pavlov et al. 2003; Kobayashi & Kronenberg, 2005; Perkins et al. 2005). One of the controlling factors of complete eye migration may coincide with the controlling factors of chondrocyte cycles. Sæle et al. (2003) demonstrate a nutritional effect on eye migration, possibly through control of chondrocytes, such as the action of vitamin A. Proliferation of chondrocytes is inhibited by retinoids through both RAR and RXR (Hagiwara et al. 1996). Inhibition of RAR signalling will initiate the expression of Sox9, the ‘master switch’ of differentiation of chondroblasts (Hoffman et al. 2003). Such a hypothesis entails a very localized mechanism of control of eye migration, but one that can have multiple consequences as subsequent tissue plasticity is affected.

Additional scenarios implicated in the cause of abnormal eye migration involve such factors as low general energy status acting on the thyroid axis, although the specific mechanisms of action of the thyroid axis on bone development are not clear. Nutritional status has rapid effects on thyroidal status in all vertebrates. T4 levels decrease rapidly (in hours) during starvation in fish but T3 decrease is delayed as a result of enzymatic control (VanderGeyten et al. 1998).

The abnormal symmetry of enzyme expression indicates that normally there is a differential expression of an osteoclastic controlling factor. The differentiated osteoclastic activity is not expressed until the ‘bending’ of the frontal processes by the lamina precerebralis of the ethmoid plate has taken place, after an asymmetric signal has affected chondrogenesis and osteoblastic activity. This suggests that asymmetric cartilage and bone growth is needed for differentiated bone absorption. A candidate pathway for this regulation is the OPG/RANKL/RANK system, where RANKL is the osteoclast differentiation factor expressed by osteoblastic/stromal cells (Khosla, 2001; Boyle et al. 2003) and cartilage (Komuro et al. 2001). According to Yamamoto et al. (2003) the presence of the optic vesicle controls the modelling of the orbital bones. When the optic vesicle is present, the edge of the orbital bones develop a well-defined perimeter around the prospective eye, whereas when the optic vesicle is not present, the orbital bones will continue to expand over the area where the eye should be. This may be a result of the OPG/RANKL/RANK signalling from the cartilage of the optic vesicle to osteoclasts remodelling the orbital bones. The same pathways may be in play when the migrating eye is ‘catching up’ with the migrated frontals, which coincides with a peak in osteoclastic activity in the posterior frontal region where the ossified bones are broadest and can otherwise obstruct the migrating eye. By contrast, in abnormal juveniles, the symmetric frontal processes are equidistant to both eyes and display equal osteoclastic activity.

Conclusion

We propose that flatfish eye migration starts with differentiated growth in the lamina precerebralis part of the ethmoid plate. Concurrently, the frontal processes are pushed and grow in the future ocular direction. Subsequently, a cell condensation of fibroblasts proliferates from the future abocular lateral part of the ethmoid plate and expands caudally, ventral to the eye (Okada et al. 2001, 2003a; Sæle et al. in press). This is followed by growth of the dense fibroblastic layer and the dermis in the dorsal direction, which together push the migrating eye towards the dorsal margin. When the migrating eye approaches the frontal process, the ossified elements are remodelled, possibly through the action of cell-to-cell signalling which initiates the final osteoclastic activity. Thus, all elements necessary for full eye migration in flatfish may be present in the anterior neurocranium, and subject to a cascade of events starting from early, normally asymmetric signalling.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Yoshiyuki Yamamoto for instructive and inspiring dialogue. Dr Anne Huysseune and Dr P. Eckhard Witten provided constructive discussions. This work was carried out with the financial support of the European Communities, Quality of Life and Management of Living Resources programme, project Q5RS-2002-01192 ‘Arrested Development: the molecular and endocrine basis of flatfish metamorphosis (ARRDE)’. This work does not represent the opinion of the European Community, which is thus not responsible for any use of the data presented.

References

- Benjamin M. Mucochondroid (mucous connective) tissues in the heads of teleosts. Anat Embryol. 1988;178:461–474. doi: 10.1007/BF00306053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornsson BT, Halldorsson O, Haux C, Norberg B, Brown CL. Photoperiod control of sexual maturation of the Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus): plasma thyroid hormone calcium levels. Aquaculture. 1998;166:117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003;423:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature01658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster B. Eye migration and cranial development during flatfish metamorphosis: a reappraisal (teleostei: Pleuronectiformes) J Fish Biol. 1987;31:805–833. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara H, Inoue A, Nakajo S, et al. Inhibition of proliferation of chondrocytes by specific receptors in response to retinoids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;222:220–224. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harboe T, Tuene S, Mangor Jensen A, Rabben H, Huse I. Design and operation of an incubator for yolk-sac larvae of Atlantic halibut. Progr Fish-Cult. 1994;56:188–193. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman UM, Weston AD, Underhill TM. Molecular mechanisms regulating chondroblast differentiation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85A:124–132. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300002-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto M, Yagami K, Shapiro IM, et al. Retinoic acid is a major regulator of chondrocyte maturation and matrix mineralization. Microsc Res Techniq. 1994;28:483–491. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070280604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto M, Kitagaki J, Tamamura Y, et al. Runx2 expression and action in chondrocytes are regulated by retinoid signaling and parathyroid hormone-related peptide (pthrp) Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2003;11:6–15. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla S. Minireview: The OPG/RANKL/RANK system. Endocrinology. 2001;142:5050–5055. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.12.8536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SG, Akaike T, Sasagawa T, Atomi K, Kurosawa H. Gene expression of type I and type III collagen by mechanical stretch in anterior cruciate ligament cells. Cell Struct Funct. 2002;27:139–144. doi: 10.1247/csf.27.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Kronenberg H. Minireview: Transcriptional regulation in development of bone. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1012–1017. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komuro H, Olee T, Kuhn K, et al. The osteoprotegerin/receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa b/receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa b ligand system in cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2768–2776. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2768::aid-art464>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langevin HM, Bouffard NA, Badger GJ, Iatridis JC, Howe AK. Dynamic fibroblast cytoskeletal response to subcutaneous tissue stretch ex vivo and in vivo. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C747–C756. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00420.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangor-Jensen A, Harboe T, Henno JS, Troland R. Design and operation of Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus L.) egg incubators. Aquacult Res. 1998;29:887–892. [Google Scholar]

- Meckel JF. Anatomisch-physiologische untersuchungen. Halle: 1822. [Google Scholar]

- Meunier FJ, Huysseune A. The concept of bone tissue in osteichthyes. Neth J Zool. 1992;42:445–458. [Google Scholar]

- Moss ML. Studies of the acellular bone of teleost fish. Acta Anat. 1961;46:343–462. doi: 10.1159/000141826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidlinger-Wilke C, Grood E, Claes L, Brand R. Fibroblast orientation to stretch begins within three hours. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:953–956. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada N, Takagi Y, Seikai T, Tanaka M, Tagawa M. Asymmetrical development of bones and soft tissues during eye migration of metamorphosing Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) Cell Tissue Res. 2001;304:59–66. doi: 10.1007/s004410100353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada N, Takagi Y, Tanaka M, Tagawa M. Fine structure of soft and hard tissues involved in eye migration in metamorphosing Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) Anat Rec Part A. 2003a;273A:663–668. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada N, Tanaka M, Tagawa M. Histological study of deformity in eye location in Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Fish Sci. 2003b;69:777–784. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov MI, Sautier JM, Oboeuf M, Asselin A, Berdal A. Chondrogenic differentiation during midfacial development in the mouse: in vivo and in vitro studies. Biol Cell. 2003;95:75–86. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(03)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins GL, Derfoul A, Ast A, Hall DJ. An inhibitor of the stretch-activated cation receptor exerts a potent effect on chondrocyte phenotype. Differentiation. 2005;73:199–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2005.00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson P, Takagi Y, Bjornsson BT. Tartrate-resistant acid-phosphatase as a masker for scale resorption in rainbow-trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss– effects of estradiol-17-beta treatment and refeeding. Fish Physiol Biochem. 1995;14:329–339. doi: 10.1007/BF00004071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson P, Sundell K, Bjornsson BT, Lundqvist H. Calcium metabolism and osmoregulation during sexual maturation of river running Atlantic salmon. J Fish Biol. 1998;52:334–349. [Google Scholar]

- Persson P, Bjornsson BT, Takagi Y. Characterization of morphology and physiological actions of scale osteoclasts in the rainbow trout. J Fish Biol. 1999;54:669–684. [Google Scholar]

- Potthoff T. Clearing and staining techniques. In: Moser HG, editor. Ontogeny and Systematics of Fishes. Lawrence: Allen Press; 1984. pp. 35–37. American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, Spec. Publ. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sæle Ø, Solbakken JS, Watanabe K, Hamre K, Pittman K. The effect of diet on ossification and eye migration in Atlantic halibut larvae (Hippoglossus hippoglossus L.) Aquaculture. 2003;220:683–696. [Google Scholar]

- Sæle Ø, Solbakken JS, Watanabe K, et al. Staging of Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus L.) from first feeding through metamorphosis, including cranial ossification independent of eye migration. Aquaculture. 2004;239:445–465. [Google Scholar]

- Sæle Ø, Smáradóttir H, Pittman K. The twisted story of eye migration in flatfish. J Morph. 2006;267:730–738. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shum L, Nuckolls G. The life cycle of chondrocytes in the developing skeleton. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2002;4:94–106. doi: 10.1186/ar396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderGeyten S, Mol KA, Pluymers W, Kuhn ER, Darras VM. Changes in plasma T-3 during fasting/refeeding in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) are mainly regulated through changes in hepatic type II iodothyronine deiodinase. Fish Physiol Biochem. 1998;19:135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wagemans F, Focant B, Vandewalle P. Early development of the cephalic skeleton in the turbot. J Fish Biol. 1998;52:166–204. [Google Scholar]

- Wagemans F, Vandewalle P. Development of the bony skull in common sole: brief survey of morpho-functional aspects of ossification sequence. J Fish Biol. 2001;59:1350–1369. [Google Scholar]

- Witten PE, Villwock W. Bone resorption by mononucleated cells during skeletal development in fish with acellular bone. J Bone Miner Res. 1997a;12(Supp. 1):F252–F252. [Google Scholar]

- Witten PE, Villwock W. Growth requires bone resorption at particular skeletal elements in a teleost fish with acellular bone (Oreochromis niloticus, teleostei: Cichlidae) J Appl Ichthyol. 1997b;13:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Witten PE, Holliday LS, Delling G, Hall BK. Immunohistochemical identification of a vacuolar proton pump (V-ATPase) in bone-resorbing cells of an advanced teleost species, Oreochromis niloticus. J Fish Biol. 1999;55:1258–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Witten PE, Villwock W, Peters N, Hall BK. Bone resorption and bone remodelling in juvenile carp, Cyprinus carpio L. J Appl Ichthyol. 2000;16:254–261. [Google Scholar]

- Witten PE, Hansen A, Hall BK. Features of mono- and multinucleated bone resorbing cells of the zebrafish Danio rerio and their contribution to skeletal development, remodeling, and growth. J Morph. 2001;250:197–207. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Espinasa L, Stock DW, Jeffery WR. Development and evolution of craniofacial patterning is mediated by eye-dependent and – independent processes in the cavefish Astyanax. Evol Dev. 2003;5:435–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2003.03050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan YL, Miller CT, Nissen R, et al. A zebrafish sox9 gene required for cartilage morphogenesis. Development. 2002;129:5065–5079. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.5065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan YL, Willoughby J, Liu D, et al. A pair of sox: distinct and overlapping functions of zebrafish sox9 co-orthologs in craniofacial and pectoral fin development. Development. 2005;132:1069–1083. doi: 10.1242/dev.01674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]