Abstract

Objective

This study examined the level, changes and predictors of alcohol consumption and binge drinking over a seven year period among young adults (18-25 years) who met criteria for problem drinking.

Method

Interviews with 270 18- to 25-years old problem and dependent drinkers from representative public and private substance use treatment programs and the general population, were conducted after 1, 3, 5, and 7 years. Measures included demographic characteristics, severity measures, and both formal and informal influences on drinking.

Results

Overall alcohol consumption declined over time but leveled off around 24 years of age. Being male, not attending AA over time, as well as more baseline dependence symptoms and greater ASI alcohol and legal severity were associated with greater consumption and binge drinking. In addition greater levels of binge drinking were associated with less education, earlier age of first use, and a larger social network of heavy drinkers.

In conclusion, more attention should be paid to heavy drinking among young adults and to the factors that influence their drinking patterns.

Keywords: Alcohol, emerging adulthood, problem drinking, longitudinal data

1. Introduction

Alcohol consumption among young people, including binge drinking, is a serious public health concern, and the prevalence of heavy drinking among 18 to 24 year olds has increased over the last decade (Chen et al., 2004). Drinking in young adults is influenced by several contributing factors, including genetic influences, ethnicity, family alcoholism, “role transition” such as marriage, health-related problems, suicide risk, and neurocognitive effects up to eight years later (e.g., (Brown & Tapert, 2004; Chassin et al., 2004; Hopfer et al., 2005; Paschall et al., 2005; Pletcher et al., 2005). Young adults, however, are more likely to have trajectories of improvement (e.g., (Fillmore, 1987).

Less well-studied are those emerging adults who already have a drinking problem. In this work we modeled both volume of alcohol and binge drinking which, while related, may provide a different perspective on behavior (Rehm, 1998). This study has three goals: (1) To describe the amount and time course of alcohol consumption and binge drinking in this sample of heavy drinking emerging adults; (2) To estimate and test a predictive model of consumption over seven years; and, (3) To compare that model of alcohol consumption to a parallel model of the frequency of binge drinking.

2. Methods

We selected all participants 18 to 25 years of age (n=265) from a larger study. The full sample was produced from two sampling procedures; details can be found in Weisner and Matzger (2002) and Weisner, Matzger, Schmidt, & Tam (2002). In-person interviews were conducted with individuals entering a county’s public and private chemical dependency programs (the treatment sample) and with problem and dependent drinkers from the general county population (general population sample) who had not received treatment in the prior year. The treatment sample (n = 926 full sample, n = 88 age 25 or younger) included consecutive admissions in the ten public and private programs in the county. The general population sample of dependent and problem drinkers not entering treatment (n = 672 full sample, n = 177 age 25 or younger) was collected using random digit dialing methods in the same county. The behaviors modeled were the base-10 log total number of drinks taken in the year prior to each assessment—the total volume of alcohol consumed—and the frequency of binge drinking, defined by the number of days in the past year when the respondent consumed three or more drinks if they were a woman and five or more if a man. Variables used are displayed as part of Table 2. Four latent variable mixed-effects growth models were estimated and tested. Two models used log-alcohol volume as the dependent variable; one without interaction terms and one with. The other two models were parallel to the first two but used frequency of binge drinking as the outcome. Rates of follow-up for this sub-sample were 86%, 83%, 81%, and 78% in Years 1, 3, 5 and 7 respectively.

Table 2.

Estimates of effects, standard errors and p-values for log-volume alcohol consumed without interaction terms and p-values for model with interaction terms.

| Effect | Volume Measure | With Interactions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Standard Error | p-value | p-value | |

|

|

||||

| Intercept | 1.660 | 0.3083 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Time – linear | −0.111 | 0.0451 | 0.014 | 0.006 |

| Time-quadratic | 0.0104 | 0.0053 | 0.049 | 0.079 |

| Demographics | ||||

| Female | −0.228 | 0.0607 | < 0.001 | 0.051 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Black v. White | −0.189 | 0.1051 | 0.073 | 0.068 |

| Hispanic v. White | −0.160 | 0.0844 | 0.060 | 0.044 |

| Other v. White | −0.13 | 0.0930 | 0.149 | 0.121 |

| Age | 0.013 | 0.0153 | 0.396 | 0.449 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Formerly Married v. Never | −0.088 | 0.1081 | 0.414 | 0.404 |

| Married v. Never | −0.097 | 0.0483 | 0.044 | 0.054 |

| Years of School | −0.028 | 0.0207 | 0.176 | 0.169 |

| Income | 0.007 | 0.0057 | 0.220 | 0.234 |

| General Pop. Sample | 0.522 | 0.0756 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| DSM-IV Dependent | 0.243 | 0.0725 | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

| No Family Alcohol Prob. | −0.079 | 0.0685 | 0.251 | 0.313 |

| Age of First Use | −0.023 | 0.0110 | 0.038 | 0.011 |

| Severity | ||||

| N Dependence Symptoms | 0.178 | 0.0125 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| N Alcohol-Related Events | 0.079 | 0.0303 | 0.009 | 0.825 |

| ASI Alcohol Severity | 1.572 | 0.1847 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| ASI Psychiatric Severity | −0.027 | 0.1431 | 0.850 | 0.829 |

| ASI Medical Severity | −0.031 | 0.0911 | 0.736 | 0.988 |

| ASI Drug Severity | 0.434 | 0.3946 | 0.271 | 0.286 |

| ASI Social Severity | −0.056 | 0.1343 | 0.675 | 0.719 |

| ASI Legal Severity | 0.4704 | 0.1501 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| ASI Employment Severity | −0.100 | 0.0658 | 0.129 | 0.130 |

| Formal Influences | ||||

| Treatment prior year | −0.193 | 0.0731 | 0.009 | 0.002 |

| Formal Contacts | −0.049 | 0.0292 | 0.097 | 0.085 |

| Informal Influences | ||||

| No AA meetings | 0.3526 | 0.0627 | < 0.001 | 0.117 |

| Size of Drinking/Drug Using Social Network | 0.003 | 0.0028 | 0.258 | 0.198 |

| Suggestions to Get Help | −0.069 | 0.0568 | 0.231 | 0.199 |

|

|

||||

| Time by Gender | 0.351 | |||

| Time by Sample | 0.066 | |||

| Time by Age of First Use | 0.141 | |||

| Time by N Consequences | 0.029 | |||

| Time by AA Attendance | 0.009 | |||

|

|

||||

| BIC | 2130.4 | 2144.5 | ||

BIC - Bayesian Information Criterion

P-values < 0.05 in bold font

3. Results

Baseline descriptors of the young adults in the sample are shown in Table 1, broken down by their alcohol dependence status, a potentially confounding variable.

Table 1.

Percentages, means, and standard deviations of baseline demographic and alcohol-related measures of the young adult respondents by dependence status.

| Problem Drinkers (N=196) | Alcohol Dependent (n=69) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |||||

| Ethnicity (%) | |||||

| White | 70.9 | 51.5 | 0.017 | ||

| Black | 7.6 | 14.7 | |||

| Hispanic | 13.3 | 16.2 | |||

| Other | 8.2 | 17.6 | |||

| Education (%) | |||||

| < High School | 17.4 | 30.4 | 0.126 | ||

| High School | 57.1 | 53.6 | |||

| Graduate | |||||

| > High School | 25.5 | 16.0 | |||

| Income <$25,000(%) | 50.5 | 50.0 | 0.940 | ||

| Male (%) | 59.7 | 65.2 | 0.418 | ||

| Never Married (%) | 81.1 | 79.7 | 0.798 | ||

| Went to AA (%) | 29.6 | 50.7 | 0.002 | ||

| No suggestions tx (%) | 92.9 | 78.6 | 0.001 | ||

|

| |||||

| Problem Drinkers (N=196) | Alcohol Dependent (n=69) | p-value | |||

|

| |||||

| Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | ||

|

|

|||||

| Age of respondent | 21.08 | 2.26 | 21.27 | 2.58 | 0.563 |

| N drinks, yearly | 897.34 | 1168.83 | 2180.37 | 1827.44 | < 0.001 |

| Log(10) of N drinks, yearly | 2.53 | 0.72 | 3.09 | 0.57 | < 0.001 |

| Per year 5-12+ drinks | 4.80 | 2.28 | 3.06 | 2.11 | <0.001 |

| Per year 5+(men) 3+ women | 90.30 | 131.03 | 214.94 | 182.52 | <0.001 |

| Age of regular use | 18.74 | 3.10 | 17.20 | 3.45 | 0.001 |

| Problematic drinking measure | 2.35 | 1.72 | 5.07 | 2.28 | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol Severity | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.23 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Related Events | 0.36 | 0.81 | 1.23 | 1.24 | < 0.001 |

| Social Severity, etc. | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.27 | <0.001 |

| Number of using people | 4.40 | 5.91 | 6.12 | 10.51 | 0.097 |

| ASI-Psychiatric | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.38 | 0.23 | < 0.001 |

| ASI-medical | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.621 |

| ASI-all Drug | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.001 |

| ASI-legal | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.20 | < 0.001 |

| ASI-employment | 0.58 | 0.34 | 0.64 | 0.33 | 0.037 |

Consumption

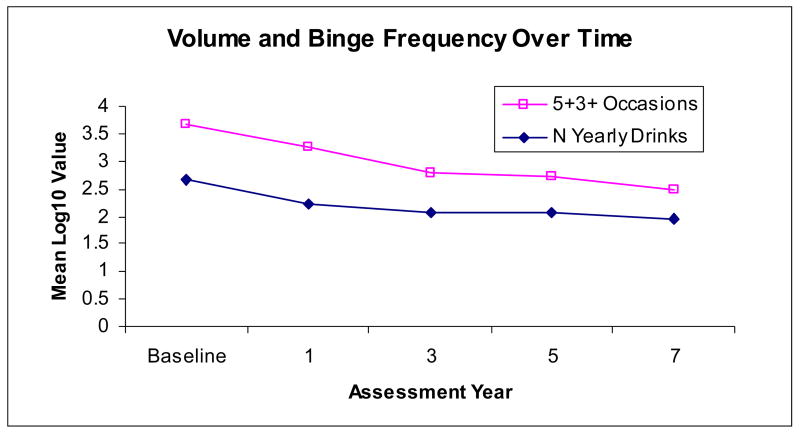

Over the seven years, mean consumption declined significantly (p = .014). While the frequency of binge drinking also declined, the change did not reach statistical significance (p = .109). The log-transformed means of the two measures of drinking are graphed in Figure 1. The median (raw scale) number of drinks per year was 564, 290, 190, 173, and 139 over the five assessments. Similarly, the median number of binge occasions dropped over time; 48, 29, 18, 16, and 11. Given the decline in drinking, it was not unexpected to find the number of participants experiencing alcohol-related problems declining over time from 93 (35%) reporting having had an event in the prior year down to only 24 (11%) experiencing a negative alcohol-related event in Year 7. Not all study participants drank alcohol in all years. Out of the 265 respondents, 121 (45.7%) reported not drinking in at least one of the years prior to an assessment while 73 (27.5%) did not drink alcohol in the year leading up to an assessment which followed one wherein they reported no consumption in the prior year. Table 2 displays the estimates, the standard errors and associated p-values for the statistical model of log-transformed alcohol volume consumed. Several measures were significantly predictive over the seven years. As noted and reflected in Figure 1, drinking declined over time but leveled off around Year 3 when the mean age was 24 (i.e., significant time and quadratic-time effects).

Figure 1.

Mean yearly volume of alcohol consumed (n drinks) and frequency of drinking 3+ (women) or 5+ (men) drinks on a single occasion—both on the base-10 log scale.

Note: Scales for two measures are not the same; 5+3+ Occasions is in log-day and N Yearly drinks is in log-drinks.

Binge Drinking

When the same model was re-estimated with the measure of binge drinking as the dependent variable, the estimates were all in the same direction, with one exception, and largely similar in value. Table 3 displays the estimates, the standard errors and associated p-values for this model which did not fit the data as well as the model for log-volume (BIC volume = 2130.4 vs. 3315.2). Change in bingeing over time, however, was no longer significant (p = .109). The time-varying index of having had alcohol treatment in the prior year was not significant in this model with a noticeable change in the p-value from p = .009 in modeling volume to p = .944 here. Also, the contrast between married and never married respondents was no longer significant (p = .184). Years of schooling, however, was significant in this model (p = .002) with a negative sign indicating more education was related to less binge drinking. The exception to the direction of effects was found for gender. The estimate (.322, p = .101) indicates that, when statistically controlling for all of the other measures, women binge more than men. The means at each assessment are greater for the men, and attempts to pinpoint a single or small set of covariates responsible for this reversal failed, suggesting a complex relationship. Examination of the distributions of the binge measure did not vary markedly between genders; the distributions of the residuals were reasonable and the proportions indicating they did not binge at all did not differ between genders (not shown).

Table 3.

Estimates of effects, standard errors and p-values for binge drinking without interaction terms and p-values for model with interaction terms.

| Effect | Binge Measure | With Interactions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Standard Error | p-value | p-value | |

|

|

||||

| Intercept | 1.909 | 0.6348 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| Time – linear | −0.160 | 0.1001 | 0.109 | 0.025 |

| Time-quadratic | 0.0111 | 0.0119 | 0.351 | 0.319 |

| Demographics | ||||

| Female | 0.322 | 0.1237 | 0.010 | 0.007 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Black v. White | −0.389 | 0.2258 | 0.086 | 0.086 |

| Hispanic v. White | −0.304 | 0.1700 | 0.076 | 0.070 |

| Other v. White | −0.121 | 0.1921 | 0.528 | 0.486 |

| Age | 0.053 | 0.0314 | 0.093 | 0.099 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Formerly Married v. Never | −0.153 | 0.2439 | 0.530 | 0.507 |

| Married v. Never | −0.142 | 0.1068 | 0.184 | 0.265 |

| Years of School | −0.129 | 0.0415 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Income | 0.0125 | 0.0122 | 0.309 | 0.334 |

| General Pop. Sample | 0.769 | 0.1618 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| DSM-IV Dependent | 0.435 | 0.1484 | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| No Family Alcohol Prob. | −0.099 | 0.1385 | 0.477 | 0.558 |

| Age of First Use | −0.084 | 0.0226 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Severity | ||||

| N Dependence Symptoms | 0.337 | 0.0269 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| N Alcohol-Related Events | 0.175 | 0.0649 | 0.007 | 0.867 |

| ASI Alcohol Severity | 3.193 | 0.3985 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| ASI Psychiatric Severity | −0.208 | 0.3113 | 0.503 | 0.553 |

| ASI Medical Severity | 0.011 | 0.2008 | 0.954 | 0.722 |

| ASI Drug Severity | 1.102 | 0.8683 | 0.205 | 0.238 |

| ASI Social Severity | −0.388 | 0.2953 | 0.189 | 0.194 |

| ASI Legal Severity | 0.750 | 0.3249 | 0.021 | 0.019 |

| ASI Employment Severity | −0.243 | 0.1500 | 0.106 | 0.133 |

| Formal Influences | ||||

| Treatment prior year | 0.011 | 0.1613 | 0.944 | 0.513 |

| Formal Contacts | −0.088 | 0.0642 | 0.168 | 0.155 |

| Informal Influences | ||||

| No AA meetings | 0.411 | 0.1365 | 0.003 | 0.231 |

| Size of Drinking/Drug Using Social Network | 0.013 | 0.0060 | 0.034 | 0.025 |

| Suggestions to Get Help | 0.079 | 0.12600 | 0.532 | 0.681 |

| Time by Gender | 0.217 | |||

| Time by Sample | 0.056 | |||

| Time by Age of First Use | 0.045 | |||

| Time by N Consequences | 0.015 | |||

| Time by AA Attendance | 0.331 | |||

|

|

||||

| BIC | 3315.2 | 3329.6 | ||

BIC - Bayesian Information Criterion

P-values < 0.05 in bold font

Change Over Time

To test for differences in the change over time, the models for both alcohol volume and binge drinking were re-estimated with the addition of interaction terms between the year of assessment (i.e., time) and five significant predictors; gender, treatment or general population sample, age of first use, number of alcohol-related consequences, and whether they attended AA. The p-values for these terms are tabled in the last column of Tables 2 and 3. For both dependent variables the estimates and p-values were generally very similar between models with and without the interaction terms. The one notable exception was that the number of negative alcohol-related events was no longer significant (p = .825), but the interaction term including that measure was (p = .029). In the binge model, similar to the model of volume, the addition of the interaction terms produced a loss of significance for the number of alcohol-related events, from p = .007 to p = .867. Change in binge drinking over time was now significant for this model and the positive sign on gender remained. As with volume, the relationship between the number of events and consumption increased over time. The interaction with age of first use was also significant, with the level of the negative correlation (lower age of first use relating to increased binge drinking) declining over time to near zero.

4. Discussion

As they aged, this sample of young adults demonstrated an overall decline in alcohol consumption. This is consistent with the findings of Brown and colleagues (Brown et al., 2001) and the findings summarized by Chung (Chung et al., 2003), and our findings extend those results to binge drinking as well. It should also be noted however that, in general, many continued to consume alcohol and only a small proportion maintained abstinence—a finding also seen by Jackson, et al. (Jackson et al., 2001). While the overall averages for both volume and binge drinking declined, they appeared to level off at an average age of about 24 years, which is about the end of this emergent adulthood period. This is consistent with recent findings (Casswell et al., 2002; Poelen et al., 2005). Being male, being dependent, age of first use, higher severity and no AA attendance were significant predictors of both greater drinking volume and binge drinking. In addition, receiving treatment in the year prior to assessment was related to decreased volume but not bingeing, while, conversely, a larger drug and heavy alcohol using social network was predictive of binge drinking but not of volume.

The most unexpected finding was the unpredicted greater level of binge drinking among women once the other measures were included in the statistical model. This suggests that if one were to find two heavy drinking samples of young adults who were identical on everything except their sex, the women would tend to binge more over time than men. More recent studies from college studies have documented increased binge drinking among young women – as a badge of honor to be able to drink “like a guy” as well as to receive positive attention from male peers (Young et al., 2005). In our case, this finding may also be a function of this particular sample—women in the stage of emerging adulthood who already are problem drinkers. Unlike findings reported by Grella and Abrantes but in concert with the results of Chung, we found no evidence of gender differences in changes in consumption (Chung et al., 2003). Also, in the models with interaction terms the genders did not change differentially over time on either of the behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by RO1AA09750, PO50-AA05595, and P50DA09253. Portions of this work were presented at the 28th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, June 30, 2005.

The authors wish to thank Lee Kaskutas, Ph.D. for a careful reading of an early draft and several helpful suggestions, Lyndsay Ammon for data management, and Priya Kamat for editorial help.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Brown SA, D’Amico EJ, McCarthy DM, Tapert SF. Four-year outcomes from adolescent alcohol and drug treatment. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 2001;62(3):381–388. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Tapert SF. Adolescent brain development: Vulnerabilities and opportunities. Vol. 1021. 2004. Adolescence and the trajectory of alcohol use: Basic to clinical studies; pp. 234–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casswell S, Pledger M, Pratap S. Trajectories of drinking from 18 to 26 years: Identification and prediction. Addiction. 2002;97(11):1427–1437. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Flora DB, King KM. Trajectories of alcohol and drug use and dependence from adolescence to adulthood: The effects of familial alcoholism and personality. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(4):483–498. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CM, Dufour MC, Yi HY. Alcohol consumption among young adults ages 18–24 in the united states: Results from the 2001–2002 nesarc. Alcohol Research & Health. 2004;28(4):269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Martin CS, Grella CE, Winters KC, Abrantes AM, Brown SA. Course of alcohol problems in treated adolescents. Alcoholism-Clinical And Experimental Research. 2003;27(2):253–261. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000053009.66472.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore KM. Prevalence, incidence and chronicity of drinking patterns and problems among men as a function of age - a longitudinal and cohort analysis. British Journal Of Addiction. 1987;82(1):77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfer CJ, Timberlake D, Haberstick B, Lessem JM, Ehringer MA, Smolen A, et al. Genetic influences on quantity of alcohol consumed by adolescents and young adults. Drug And Alcohol Dependence. 2005;78(2):187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Gotham HJ, Wood PK. Transitioning into and out of large-effect drinking in young adulthood. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110(3):378–391. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Bersamin M, Flewelling RL. Racial/ethnic differences in the association between college attendance and heavy alcohol use: A national study. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 2005;66(2):266–274. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletcher MJ, Varosy P, Kiefe CI, Lewis CE, Sidney S, Hulley SB. Alcohol consumption, binge drinking, and early coronary calcification: Findings from the coronary artery risk development in young adults (cardia) study. American Journal Of Epidemiology. 2005;161(5):423–433. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poelen EAP, Scholte RHJ, Engels R, Boomsma DI, Willemsen G. Prevalence and trends of alcohol use and misuse among adolescents and young adults in the Netherlands from 1993 to 2000. Drug And Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79(3):413–421. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J. Measuring quantity, frequency, and volume of drinking. Alcoholism-Clinical And Experimental Research. 1998;22(2):4S–14S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-199802001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Matzger H. A prospective study of the factors influencing entry to alcohol and drug treatment. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2002;29(2):126–137. doi: 10.1007/BF02287699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Matzger H, Tam T, Schmidt L. Who goes to alcohol and drug treatment? - understanding utilization within the context of insurance. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(6):673–682. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Morales M, McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, D’Arcy H. Drinking like a guy: Frequent binge drinking among undergraduate women. Substance Use & Misuse. 2005;40(2):241–267. doi: 10.1081/ja-200048464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]