Abstract

The advent of hybridoma technology has made it possible to study in depth individual antibody molecules. These studies have revealed a number of surprises that have and are continuing to change our view of the immune system. None of these was more surprising than the demonstration that many antibody molecules are polyreactive – that is they can bind to a variety of different and structurally unrelated self and non-self foreign antigens. These findings make it clear that self-reactivity is a common and not necessarily forbidden or pathogenic feature of the immune system and that the well known broad anti-bacterial activity of natural antibodies is largely due to polyreactive antibodies. In this brief review we will discuss these insights and their impact on basic and clinical immunology.

Keywords: Polyreactive antibody, Natural antibody, B cell, Autoantibody, Bacteria

1. Introduction

In the early 1980's, to see if viruses might be one of the triggers of autoimmunity we infected mice with reovirus. The infected animals developed a mild form of diabetes and their sera contained a number of antibodies that reacted with normal tissues [1]. Because the titer of these antibodies was very low and therefore difficult to characterize, we thought that the best way to study them was to obtain lymphocytes from the spleen and prepare hybridomas. We found that many of the hybridomas made monoclonal antibodies that reacted with perfectly normal tissues, but to our great surprise many of the monoclonal antibodies reacted not with a single organ or cell type, but with a number of different organs and cell types [2]. In depth studies revealed that these monoclonal antibodies were not reacting with the same antigen in different tissues or a single cross-reactive antigen, but instead with a number of different and unrelated antigens [3, 4]. We called these antibodies polyreactive antibodies.

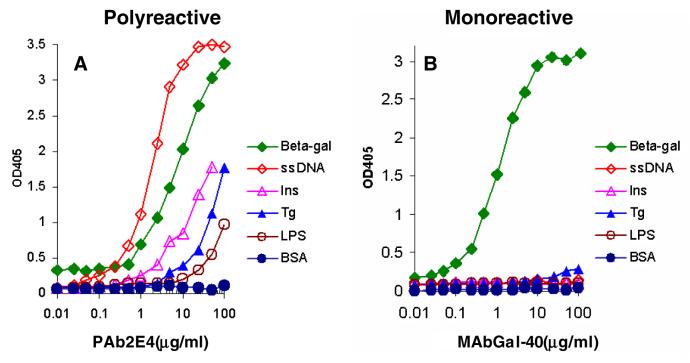

At first we thought that polyreactive antibodies were autoantibodies because we found them in the virus-infected mice. But then we made a number of hybridomas from normal uninfected mice and found essentially the same thing [4, 5]. That is, the hybridomas from perfectly normal mice made polyreactive antibodies that reacted with normal tissues (Figure 1). At about the same time, similar observations were being made independently by Stratis Avrameas at the Pasteur Institute [6-8].

Fig. 1.

Binding of a murine monoclonal polyreactive IgM antibody (PAb2E4) to different normal tissues.

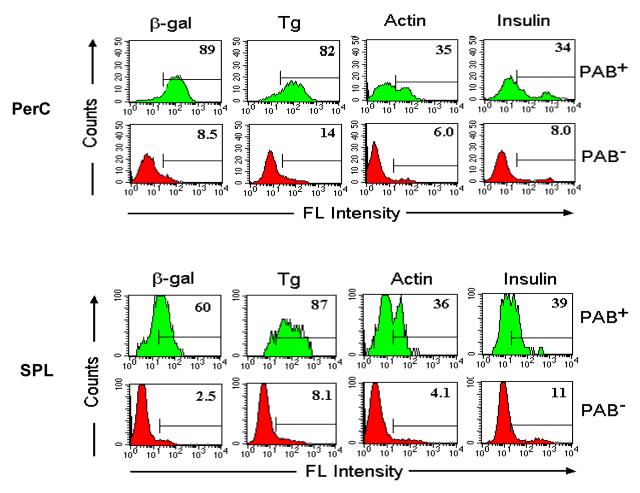

To study polyreactive antibodies more quantitatively we examined their reactivity with a panel of purified antigens (Figure 2). The panel on the left represents a typical monoclonal polyreactive antibody as evaluated by ELISA and shows that polyreactive antibodies react not only with self-antigens, but equally well with a variety of foreign antigens. Dozens of these polyreactive antibodies then were made and each was found to have a slightly different fine specificity pattern of reactivity with different antigens [5]. In contrast, the panel on the right shows the reactivity of a typical monoclonal monoreactive antibody that was obtained following immunization with a known antigen. This antibody reacted only with its cognate antigen and not with any of the other antigens recognized by the polyreactive antibody. This difference in binding pattern illustrates the fundamental difference between the classic type of monoclonal monoreactive antibody and monoclonal polyreactive antibody. Polyreactive antibodies now have been found in all jawed vertebrates examined from humans to the shark indicating that these antibodies are an ancient and highly conserved feature of the immune system [9, 10].

Fig. 2. Binding of antigens by monoclonal polyreactive (PAb2E4) and moclonal monoreactive (MAb GAL-40) antibodies.

(A) Polyreactive antibody PAb2E4 binds strongly to β-galactase (β-gal) and single-stranded DNA (ss-DNA) and moderately to insulin, thyroglobulin (Tg) and LPS, whereas (B) while monoreactive antibody MAbGal-40 only recognizes its cognate antigen, β-gal [23].

2. Properties of polyreactive antibodies

The major properties of polyreactive antibodies are summarized in Table 1 [5, 7, 11]. The majority of these antibodies are IgM, but some are IgA and IgG. The affinity of a polyreactive antibody for different antigens varies by as much as 1000 fold and in general is considerably lower (Kd, 10−4 to 10−7 mol l−1) then that of monoreactive antibody for its cognate antigen (Kd, 10−7 to 10−11 mol l−1). Sequence analysis has revealed that many of the polyreactive antibodies are germline or near germline although some show a small to moderate number of substitutions. Of particular interest is the rate at which polyreactive antibodies are cleared from the circulation [12]. The half-life of polyreactive IgM, IgA and IgG in the circulation of mice is 8, 8 and 10 hours, respectively. In contrast, the half-life of monoreactive IgM, IgA and IgG is 35, 26 and 280 hours, respectively. The rapid clearance of the polyreactive antibodies is thought to be due to the binding of these antibodies to endogenous host antigens. Similarly, in the circulation, the level of polyreactive antibodies is low because much of it is bound to proteins in the serum. If, however, the IgM in sera is first affinity-purified to dissociate bound antigens, the affinity-purified IgM shows substantial polyreactivity [13].

Table 1.

Properties of monoclonal polyreactive Abs as compared to monoclonal monoreactive Abs

| Polyreactive mAb | Monoreactive mAb | |

|---|---|---|

| Antigen | Structurally-diverse Ags (e.g., proteins, bacteria, DNA, haptens) |

Single cognate Ag |

| Affinity | Low (Kd: 10−4∼10−7) | High (Kd: 10−7∼10−11 ) |

| Sequence | Germline or Near Germline | Somatically mutated |

| Ig class | Mainly IgM, but also IgA and IgG | IgG, IgM, IgA |

| Half life | IgM: ∼8 hrs; IgA: ∼8 hrs; IgG: ∼10hrs |

IgM: ∼35 hrs; IgA: ∼26 hrs; IgG: ∼280hrs |

Precisely how a monoclonal polyreactive antibody molecule can bind totally unrelated antigens and whether these antigens actually interact with the antigen-binding pocket or other regions of the polyreactive antibody molecule has been the subject of considerable experimentation and speculation. The overall consensus is that the different antigens, in fact, do bind to the antigen-binding pocket of the polyreactive antibody. However, in contrast to the rigid structure of the antigen-binding pockets visualized by the “lock and key” hypothesis to explain the binding of antigens to high affinity monoreactive antibodies, the antigen-binding pockets of low affinity germline polyreactive antibodies are thought to be considerably more flexible thereby allowing conformational changes in the binding pockets that can accommodate different antigens [11].

3. Properties of the B cells that make polyreactive antibodies

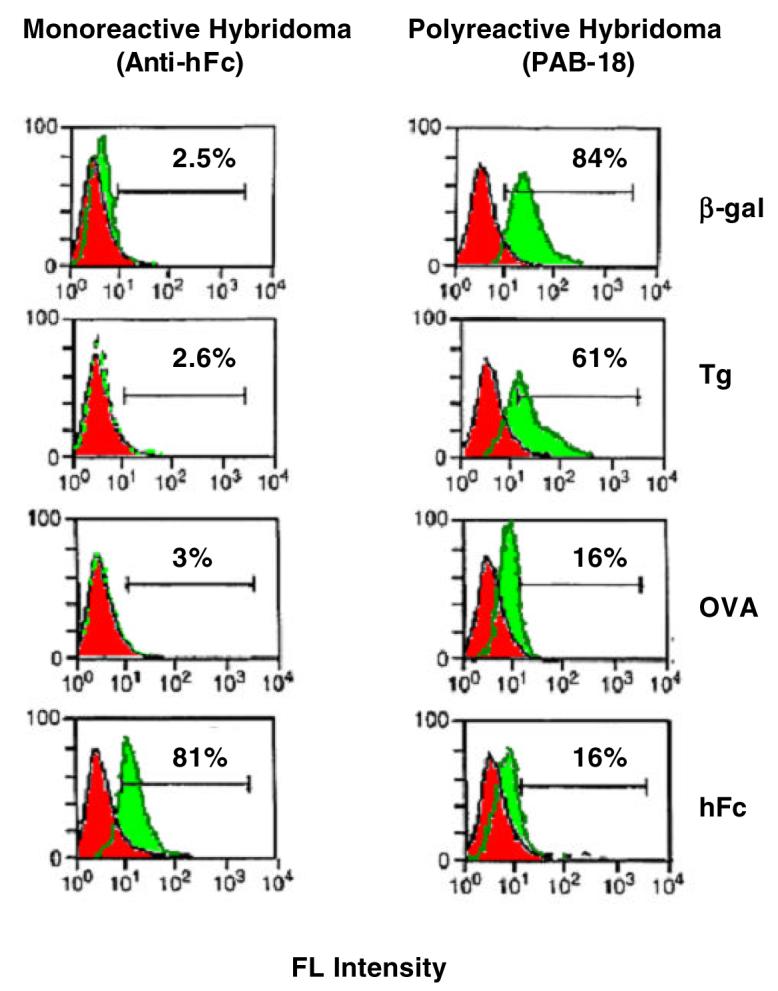

Based on the binding properties of polyreactive antibodies, we postulated that a variety of different antigens would bind to the immunoglobulin receptors on the surface of B cells that make polyreactive antibodies. To test this hypothesis, the binding of FITC-labeled antigens to hybridomas that made polyreactive (PAB-18 cells) and monoreactive (anti-hFc cells) antibodies were compared [14, 15]. As seen in Figure 3, 81% of the anti-hFc cells bound hFc, whereas less than 3% of the cells bound β-gal, Tg or OVA. In contract, 84%, 61%, 16% and 16% of the PAB-18 cells bound β-gal, Tg, OVA and hFc, respectively. We refer to these polyreactive antigen-binding B cells as PAB cells.

Fig. 3. Binding of FITC-labeled antigens to polyreactive (PAB-18) and monoreactive hybridomas (anti-hFc) cells.

Polyreactive hybridoma clone PAB-18 binds FITC-labeled β-galactase (β-gal), thyroglobulin (Tg), ovalbumin (OVA) and human IgG Fc (hFc). In contrast, the monoreactive hybridoma clone anti-hFc only binds its cognate antigen, hFc [15].

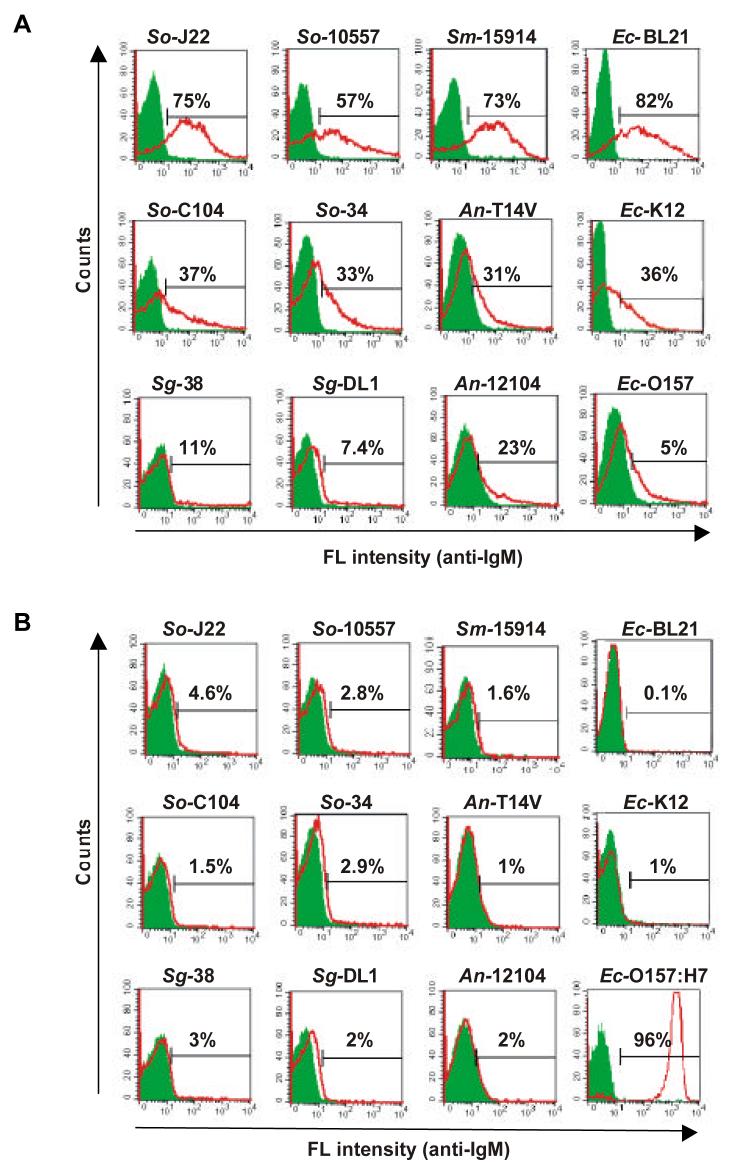

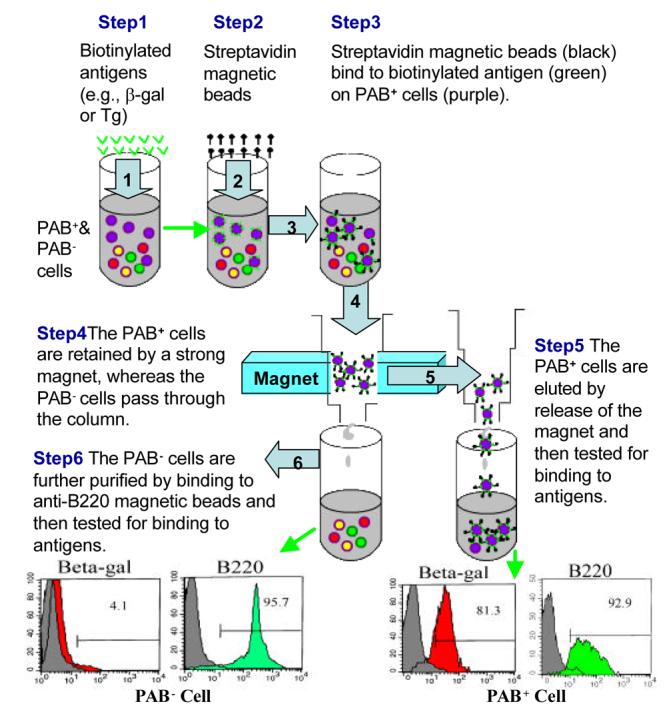

To identify and compare the antigen-binding capacity of different B cell subsets, PAB+ and PAB− cells from the peritoneal cavity and spleen were separated by use of magnetic beads coated with antigens (Figure 4). The PAB+ and PAB− cells then were tested for their ability to bind different FITC-labeled antigens [16]. As seen in Figure 5, close to 90% of the PAB+ cells from the peritoneal cavity bound β-gal, whereas less than 10% of the PAB− cells bound β-gal. Similarly, 4-6 times more of the PAB+ cells bound Tg, actin and insulin than the PAB− cells. PAB+ cells from the spleen also bound many times more antigens than PAB− cells (Figure 5). PAB+ cells also were found in Peyer's patches, lamina propria, marginal zone of the spleen and in the thymus [16]. In humans approximately 50% of the B cells in cord blood of new borns and 15% to 20% of the B cells in the peripheral circulation of adults are PAB+ cells [17].

Fig. 4.

Separation of PAB+ from PAB− cells by antigen-coated magnetic beads.

Fig. 5. Antigen-binding of PAB+ and PAB− cells from peritoneal cavity (PerC) and spleen (SPL).

PAB+ and PAB− cells from PerC and SPL of BALB/c mice were positively selected as described in Figure 4. The binding of Ags (β-gal, Tg, actin and insulin) was determined by FACS analysis. The percentage of positively stained cells is indicated [16].

To further characterize PAB+ and PAB− cells a variety of surface markers were analyzed [16], particularly those related to the B-1 phenotype (e.g., IgMhi, IgDlo, B220lo, Mac-1hi, CD23lo and CD5hi) [18, 19]. Our results showed that a high percentage of PAB+ cells express B-1+ surface markers, but many do not, and, in fact, are B-1−. For example, only 61% of the PAB+ cells in the peritoneal cavity were Mac-1hi and only 34% CD5hi (Table 2). Even a lower percentage of the PAB+ cells in the spleen were Mac-1hi (3.2%) and CD5hi (3.6%). Little, if any, difference was found between PAB+ and PAB− cells in terms of the expression of B220, sIgM or sIgD. From these and other studies we conclude that the B cell population consists of PAB+/B-1+, PAB+/B-1− , PAB−/B-1+ and PAB−/B-1− cells and that the binding of labeled antigens is the most reliable way to identify those cells that make polyreactive antibodies.

Table 2.

Surface markers expressed by PAB+ and PAB− cells

| Organ | Cell Type | Ctrl* | B220 | sIgM | sIgD | Mac-1 | CD5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PerC | PAB+ | 2.7% | 92% | 99% | 99% | 61% | 34% |

| PerC | PAB− | 3.8% | 95% | 99% | 97% | 19% | 9% |

| SPL | PAB+ | 3.7% | 93% | 89% | 97% | 3.2% | 3.6% |

| SPL | PAB− | 0.8% | 96% | 98% | 98% | 1.0% | 0.8% |

Negative control

4. Polyreactive antibodies as an explanation for the broad antibacterial activity of sera

Natural antibodies were first recognized almost 100 years ago and sera containing these antibodies have been shown to possess bactericidal activity [20-22]. To distinguish antigen-induced antibodies from natural antibodies, sera are usually diluted 10 to 50 fold before testing to reduce the background activity of the natural antibodies. These natural antibodies, however, have remained an enigma because they are found in sera in the apparent absence of antigenic stimulation and are present in sera of newborns and germ-free animals. Of particular interest is the observation made some years ago that absorption of sera with specific bacteria can result in loss of reactivity to unrelated bacteria [21]. The demonstration that monoclonal polyreactive antibodies can bind to a variety of different antigens has raised the possibility that the broad antibacterial activity of normal sera is due to polyreactive antibodies. However, because of their low titer and low binding affinity the biological importance of polyreactive antibodies has been questioned. Recently, we initiated a series of experiments showing that, in fact, in the presence of complement, polyreactive antibodies have antibacterial activity [23].

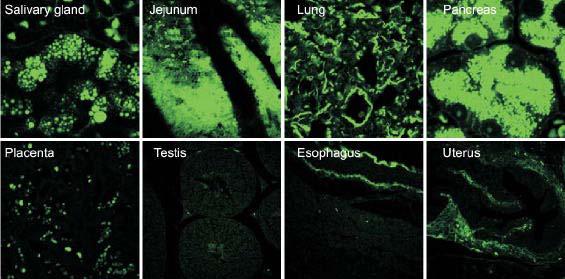

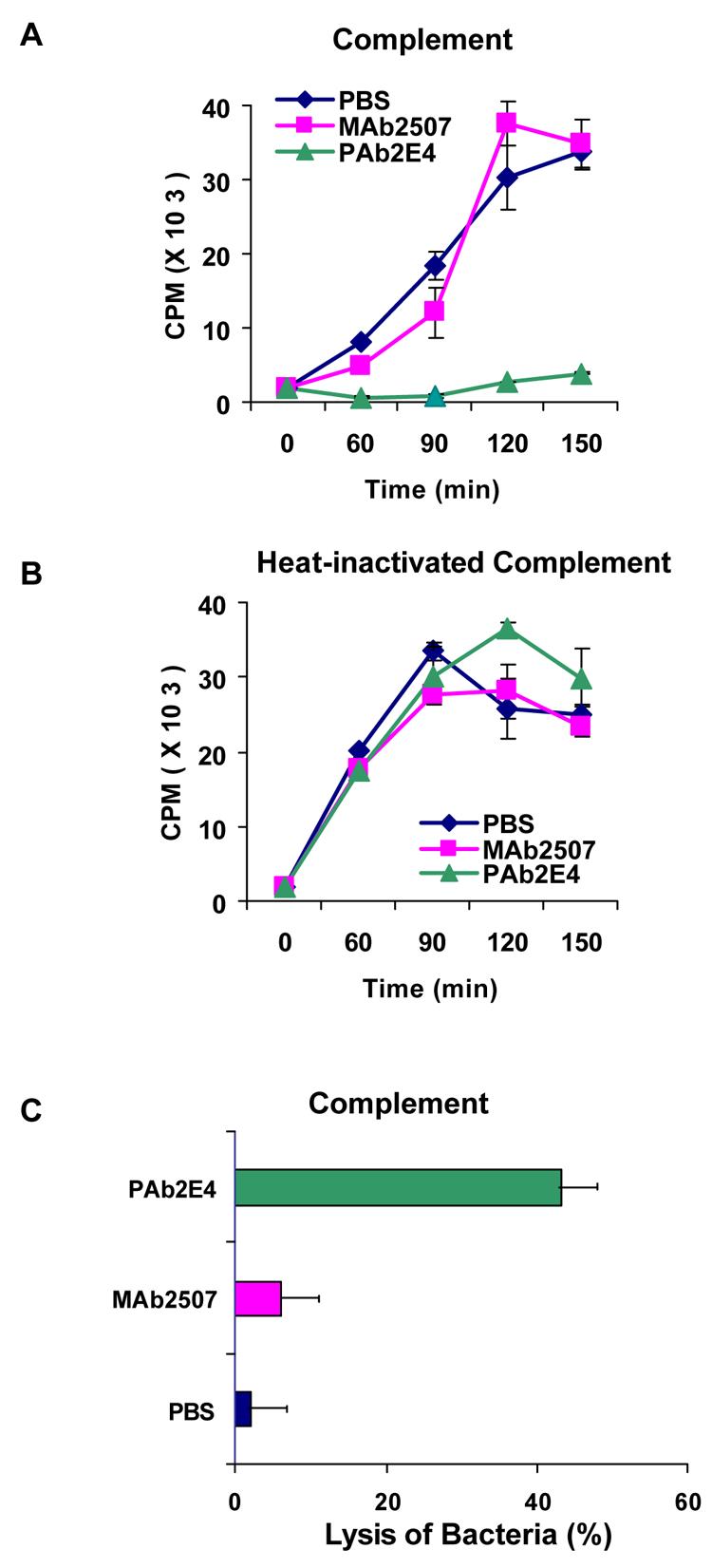

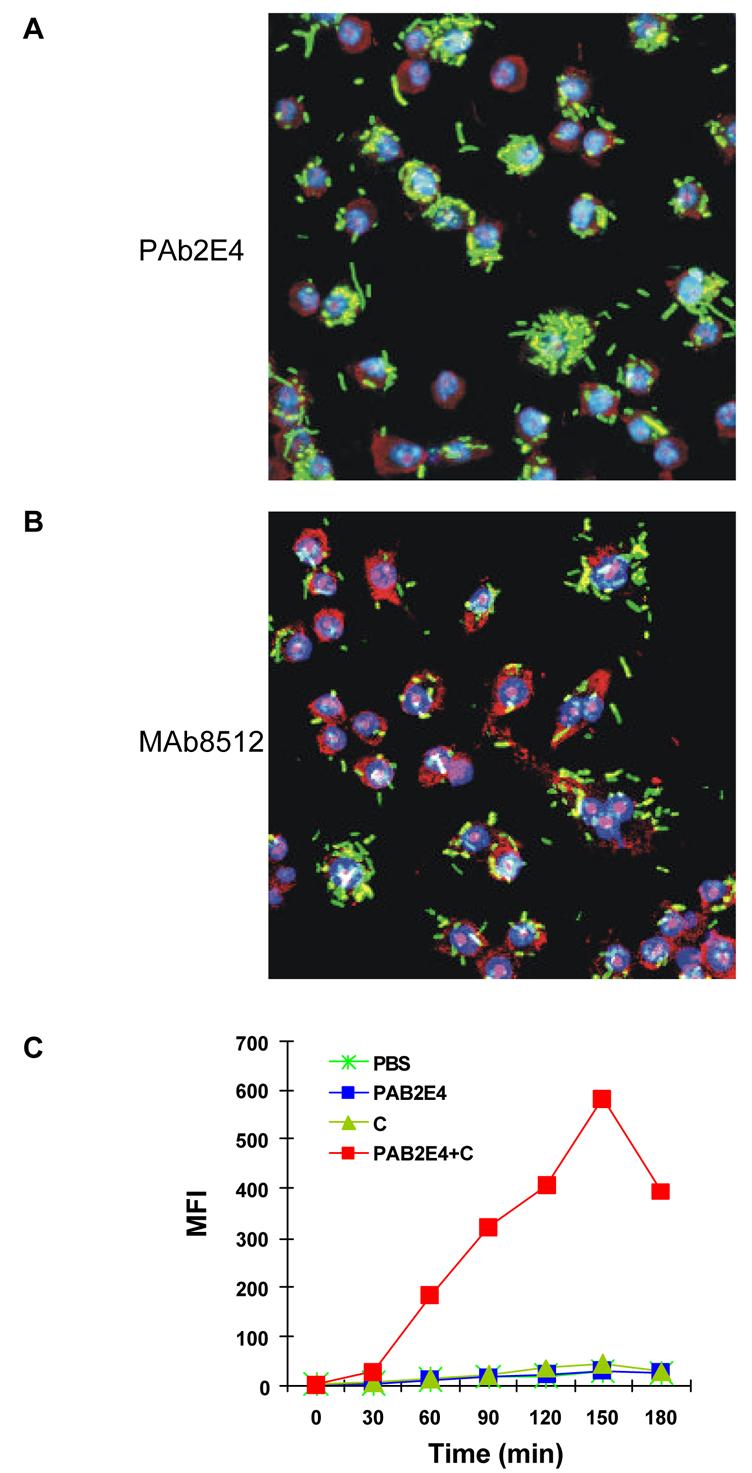

The ability of polyreactive antibody to bind to bacteria is shown in Figure 6. Monoclonal polyreactive antibody PAb2E4 binds strongly , moderately or weakly to different Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. In contrast, monoclonal monoreactive antibody MAb2507 binds only to its cognate antigen E. coli O157:H7. Further studies showed that PAb2E4 can fix complement and inhibit the growth of bacteria by lysis (Figure 7). In addition, PAb2E4, in the presence of complement, enhances bacterial phagocytosis by macrophages (Figure 8). In contrast to the bactericidal effect of PAb2E4 on Gram-negative bacteria, PAb2E4 binds to Gram-positive bacteria, but is not bactericidal. Instead, the binding results in the fixation of complement and the generation of the anaphylatoxin C5a, an important chemotaxis factor [23].

Fig. 6. Polyreactive antibody binds to various bacteria.

(A) Polyreactive antibody PAb2E4 binds strongly to some bacteria (Streptococcus oralis J22, Streptococcus oralis 10557, Streptococcus mitis 15914 and E. coli BL21), moderately to other bacteria (Streptococcus oralis C104, Streptococcus oralis 34, Actinomyces naeslundii T14V and E. coli K12) and weakly or not at all to still other bacteria (Streptococcus gordonii 38, Streptococcus gordonii DL1, Actinomyces naeslundii 12104 and E. coli O157: H7). In contrast, (B) monoclonal antibody MAb2507 binds only to its cognate antigen E. coli O157: H7. Antibody binding measured by fluorescence intensity with anti-IgM [23].

Fig. 7. Polyreactive antibody PAb2E4 inhibits bacterial growth through lysis of bacteria.

The effect of complement on the growth of bacteria treated with polyreactive antibody PAb2E4 was determined by measuring the incorporation of 3H-thymidine. (A)There was little if any incorporation of 3H-thymidine into bacteria treated with PAb2E4 as compared to bacteria that had been treated with PBS or with MAb2507. (B) In the presence of heat-inactivated complement there was no inhibition of growth. (C) Lysis of PAb2E4-treated bacteria as measured by the release of 3H-TdR in the presence of complement. Considerably more 3H-TdR was released from the cells treated with PAb2E4 than those treated with MAb2507 or PBS [23].

Fig. 8. Polyreactive antibody PAb2E4 enhances phagocytosis.

FITC-labeled bacteria (green) were treated with monoclonal antibodies and complement and then added to murine macrophages cultured in serum-free medium. The nuclei of the macrophages were prestained (blue) with Hoechst 33342. The cytoplasm of the macrophages was stained with ethidium bromide (red). (A) Substantial phagocytosis by macrophages of bacteria treated with PAb2E4 and complement. (B) Minimal phagocytosis of bacteria treated with MAb2507 and complement. (C) Phagocytosis of 2E4-treated bacteria in the presence of complement as determined by FACS analysis and expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) [23].

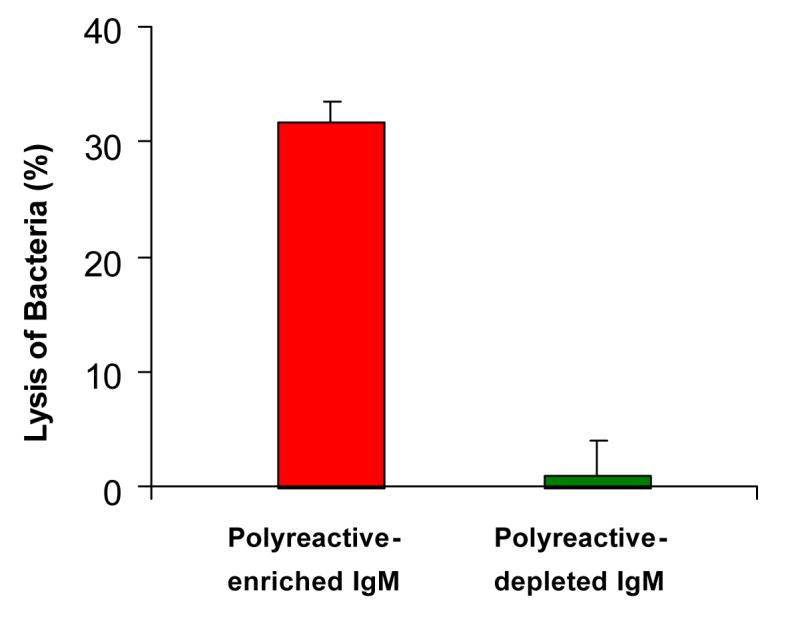

Finally, to determine whether polyreactive antibody in sera also has antibacterial activity, human sera were enriched for polyreactive antibodies by serial passage of affinity purified human IgM through three different antigen-affinity columns (i.e., ssDNA, β-gal, thyroglobulin). The polyreactive-enriched, as compared to the polyreactive-reduced, IgM bound to a variety of different antigens, fixed complement and lysed E. coli BL21 (Figure 9). We conclude from these experiments that the broad antibacterial activity of the natural antibody repertoire is largely due to polyreactive antibodies [23].

Fig. 9. Polyreactive-enriched IgM antibodies lyse bacteria.

Purified human IgM was sequentially passed through and eluted from ssDNA, β-gal and thyroglobulin affinity columns. The pass-through fractions were designated “polyreactive-depleted IgM” and the eluted fractions “polyreactive-enriched IgM”. Lysis of IgM-treated bacteria was measured by the release of 3H-TdR in the presence of complement.

5. Discussion

The studies on polyreactive antibodies have broadened our understanding of the immune system in several respects. First, upon their initial description, the very existence of polyreactive antibodies was difficult to accept because their properties seemed contrary to the generally accepted view derived from the clone selection theory, that most antibody molecules were highly specific or showed a very limited cross-reactivity. By hybridoma technology it became possible to make large numbers and quantities of monoclonal antibodies and clearly establish the widespread presence of polyreactive antibodies in jawed vertebrates from humans to sharks. Further studies showed that a major portion of the natural antibody repertoire consisted of polyreactive antibodies. Thus, polyreactivity expands even further the already enormous antigen-binding capacity of the antibody repertoire.

Second, much of modern immunology has focused on understanding how the host's immune system distinguishes between self and non-self and then eliminates or puts in a non-reactive state those lymphocytes that react with self. Paul Ehrlich's famous concept of “horror autotoxicus” often has been misinterpreted to mean that antibodies to self would be harmful and by necessity forbidden and have to be eliminated [24]. The demonstration that polyreactive antibodies can react with self and are present in all of us without causing harm shows that a distinction should be made between these naturally-occurring low affinity polyreactive antibodies and true disease-induced high affinity autoantibodies. Whereas polyreactive antibodies are primarily IgM, germline or near germline and low affinity, most disease-induced autoantibodies are IgG or IgA, somatically mutated and high affinity. Although some investigators believe that polyreactive antibodies may be precursors of high affinity pathogenic autoantibodies [25-27], until there is solid proof, polyreactive antibodies should be considered a normal self-reactive component of the immune system. In fact, it has been suggested that the B cells that make polyreactive antibodies may have a function independent of the antibodies they secrete. Since PAB cells are present in high number in the peripheral circulation of adults and are the predominant B cell type in cord blood, they are ideally resulted to bind and present endogenous host antigens to T cells. Under some circumstances this might occur without activating the costimulatory molecules B7-1 and B7-2 [14, 15, 28]. Thus PAB cells may play a role in inducing and/or maintaining immunological tolerance.

Third, it has been known for years that natural antibodies have broad antibacterial activity. It is now clear that much of the natural antibody repertoire consists of polyreactive antibodies. Although there has been much speculation about the actual function of polyreactive antibody, there is very little experimental data. Using monoclonal polyreactive antibodies our studies now have demonstrated that these antibodies have broad antibacterial activity. These findings help explain the enigma of the antibacterial activity in the sera of newborns and germ-free animals in the absence of known antigenic stimulation.

In conclusion, our studies showed that: 1) antibody molecules may be highly monoreactive or broadly polyreactive; 2) the reactivity of antibody molecules with self is not forbidden, but a common feature of the antibody repertoire; and 3) the broad antibacterial activity of the natural antibody repertoire, in large part, is due to polyreactive antibodies.

The present review, regarding the properties and function of polyreactive antibodies, was presented at a meeting on “Autoimmunity: Physiological and Pathophysiological Aspects” held in Athens, Greece on May 25-27, 2007. Other papers on the physiology and pathophysiology of autoimmunity appear elsewhere in this special issue (29-42).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Haspel MV, Onodera T, Prabhakar BS, Horita M, Suzuki H, Notkins AL. Virus-induced autoimmunity: monoclonal antibodies that react with endocrine tissues. Science. 1983;220:304–306. doi: 10.1126/science.6301002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haspel MV, Onodera T, Prabhakar BS, McClintock PR, Essani K, Ray UR, et al. Multiple organ-reactive monoclonal autoantibodies. Nature. 1983;304:73–76. doi: 10.1038/304073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satoh J, Prabhakar BS, Haspel MV, Ginsberg-Fellner F, Notkins AL. Human monoclonal autoantibodies that react with multiple endocrine organs. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:217–220. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198307283090405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prabhakar BS, Saegusa J, Onodera T, Notkins AL. Lymphocytes capable of making monoclonal autoantibodies that react with multiple organs are a common feature of the normal B cell repertoire. J Immunol. 1984;133:2815–2817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casali P, Notkins AL. Probing the human B-cell repertoire with EBV: polyreactive antibodies and CD5+ B lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:513–535. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dighiero G, Lymberi P, Mazie JC, Rouyre S, Butler-Browne GS, Whalen RG, et al. Murine hybridomas secreting natural monoclonal antibodies reacting with self antigens. J Immunol. 1983;131:2267–2272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avrameas S. Natural autoantibodies: from ‘horror autotoxicus’ to ‘gnothi seauton’. Immunol Today. 1991;12:154–159. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(05)80045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coutinho A, Kazatchkine MD, Avrameas S. Natural autoantibodies. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:812–818. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchalonis JJ, Hohman VS, Thomas C, Schluter SF. Antibody production in sharks and humans: a role for natural antibodies. Dev Comp Immunol. 1993;17:41–53. doi: 10.1016/0145-305x(93)90014-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marchalonis JJ, Adelman MK, Robey IF, Schluter SF, Edmundson AB. Exquisite specificity and peptide epitope recognition promiscuity, properties shared by antibodies from sharks to humans. J Mol Recognit. 2001;14:110–121. doi: 10.1002/jmr.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Notkins AL. Polyreactivity of antibody molecules. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sigounas G, Harindranath N, Donadel G, Notkins AL. Half-life of polyreactive antibodies. J Clin Immunol. 1994;14:134–140. doi: 10.1007/BF01541346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sigounas G, Kolaitis N, Monell-Torrens E, Notkins AL. Polyreactive IgM antibodies in the circulation are masked by antigen binding. J Clin Immunol. 1994;14:375–381. doi: 10.1007/BF01546322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen ZJ, Wheeler J, Notkins AL. Antigen-binding B cells and polyreactive antibodies. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:579–586. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Z, Chen ZJ, Wheeler J, Shen S, Notkins AL. Characterization of murine polyreactive antigen-binding B cells: presentation of antigens to T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1106–1114. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1106::aid-immu1106>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou ZH, Notkins AL. Polyreactive antigen-binding B (PAB-) cells are widely distributed and the PAB population consists of both B-1+ and B-1− phenotypes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;137:88–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen ZJ, Wheeler CJ, Shi W, Wu AJ, Yarboro CH, Gallagher M, et al. Polyreactive antigen-binding B cells are the predominant cell type in the newborn B cell repertoire. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:989–994. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199803)28:03<989::AID-IMMU989>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baumgarth N, Tung JW, Herzenberg LA. Inherent specificities in natural antibodies: a key to immune defense against pathogen invasion. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005;26:347–362. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy RR. B-1 B cells: development, selection, natural autoantibody and leukemia. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon J, Carter HS. The bactericidal power of normal serum. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1932;35:549–555. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michael JG, Whitby JL, Landy M. Studies on natural antibodies to gram-negative bacteria. J Exp Med. 1962;115:131–146. doi: 10.1084/jem.115.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tauber AI, Podolsky SH. The Generation of Diversity: Clonal Selection Theory and the Rise of Molecular Immunology. Harvard University Press; Cambridge Massachusets, USA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou ZH, Zhang Y, Hu YF, Wahl LM, Cisar JO, Notkins AL. The broad antibacterial activity of the natural antibody repertoire is due to polyreactive antibodies. Cell Host & Microbe. 2007;1:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silverstein AM. Autoimmunity versus horror autotoxicus: the struggle for recognition. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:279–281. doi: 10.1038/86280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ichiyoshi Y, Zhou M, Casali P. A human anti-insulin IgG autoantibody apparently arises through clonal selection from an insulin-specific “germ-line” natural antibody template. Analysis by V gene segment reassortment and site-directed mutagenesis. J Immunol. 1995;154:226–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wardemann H, Yurasov S, Schaefer A, Young JW, Meffre E, Nussenzweig MC. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 2003;301:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merbl Y, Zucker-Toledano M, Quintana FJ, Cohen IR. Newborn humans manifest autoantibodies to defined self molecules detected by antigen microarray informatics. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:712–718. doi: 10.1172/JCI29943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen ZJ, Shimizu F, Wheeler J, Notkins AL. Polyreactive antigen-binding B cells in the peripheral circulation are IgD+ and B7. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2916–2923. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruiz-Argüelles A, Brito GJ, Reyes-Izquierdo P, Pérez-Romano B, Sánchez-Sosa S. Apoptosis of melanocytes in vitiligo results from antibody penetration. J. Autoimmun. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.012. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zelenay S, Fontes MFM, Fesel C, Demengeot J, Coutinho A. Physiopathology of natural auto-antibodies: The case for regulation. J. Autoimmun. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.011. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papadimitraki E, Bertsias G, Boumpas DT. Toll like receptors and autoimmunity: A critical appraisal. J. Autoimmun. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.09.001. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lutz H. Homeostatic roles of naturally occurring antibodies. An overview. J. Autoimmun. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.007. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen I. Biomarkers, self-antigens and the immunological homunculus. J. Autoimmun. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.016. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasquali J-L, Soulas-Sprauel P, Korganow A-S, Martin T. Autoreactive B cells in transgenic mice. J. Autoimmun. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.006. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lang K, Burow A, Kurrer M, Lang P, Recher MJ. Balance of the innate immune response in autoimmune disease. J. Autoimmun. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.018. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peng Y, Martin DA, Kenkel J, Zhang K, Ogden CA, Elkon KB. Innate and adaptive immune response to apoptotic cells. J. Autoimmun. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.017. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vollmers H.a.B., S. Natural antibodies and cancer. J. Autoimmun. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.013. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rowley B, Tang L, Shinton S, Hayakawa K, Hardy RR. Autoreactive B-1 B cells: Constraints on natural autoantibody B cell antigen receptors. J. Autoimmun. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.020. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avrameas S, Ternynck T, Tsonis IA, Lymperi P. The immune system as emerges from studies on natural autoantibodies. J. Autoimmun. 2007 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milner J, Ward J, Keane-Myers A, Min B, Paul WE. Repertoire-dependent immunopathology. J. Autoimmun. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.019. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lan R, Mackay IR, Gershwin ME. Regulatory T cells in the prevention of mucosal inflammatory diseases: Patrolling the border. J. Autoimmun. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.021. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryan KR, Patel SD, Stephens LA, Anderton SM. Death, adaptation and regulation: the three pillars of immune tolerance restrict the risk of autoimmune disease caused by molecular mimicry. J Autoimmun. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.014. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]