Summary

Objective

Hormone-based contraceptives affect mood in healthy women or in women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. No study has yet examined their association with mood in women with major depressive disorder (MDD). The purpose of this study was to determine whether estrogen-progestin combination or progestin-only contraceptives are associated with depression severity, function and quality of life, or general medical or psychiatric comorbidity in women with MDD.

Methods

This analysis focused on a large population of female outpatients less than 40 years of age with non-psychotic MDD who were treated in 18 primary and 23 psychiatric care settings across the United States, using data from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. Baseline demographic and clinical information was gathered and compared between three groups based on hormonal use: combination (estrogen-progestin)(N=232), progestin-only (N=58), and no hormone treatment (N=948).

Results

Caucasians were significantly more likely to use combined hormone contraception. Women on progestin-only had significantly more general medical comorbidities; greater hypersomnia, weight gain and gastrointestinal symptoms; and worse physical functioning than women in either of the other groups. Those on combined hormone contraception were significantly less depressed than those with no hormone treatment by the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology - Self-Rated. The combined hormone group also demonstrated better physical functioning and less obsessive-compulsive disorder comorbidity than either of the other groups.

Conclusions

Synthetic estrogen and progestins may influence depressive and physical symptoms in depressed women.

Keywords: Estradiol, Progesterone, Major Depression, Mood symptoms, Oral contraceptives, Norplant

INTRODUCTION

The use of hormonal forms of contraception is common among women of reproductive age, the most common being a combination of synthetic estrogen (ethinyl estradiol) and synthetic progesterone (progestin). Studies that have examined the effects of these hormone treatments on mood have predominantly been conducted in populations of women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) or healthy women. Early studies using oral contraceptives with high progestin doses reported depression as a possible side effect in normal women in case series and small case-control studies (Nilson and Almgren, 1968; Herzberg et al, 1970; Worsley and Chang, 1978). A large epidemiological-based study found that among women with PMDD who were starting hormone-based contraceptives, most women showed no change in mood, with mood improving in some women and worsening in others (Joffee et al., 2003). This finding in a community-based study agrees with that of an earlier report that hormone-based contraceptives have no effect on mood in this population (Oinonen and Mazmanian, 2002). Studies of “normal women” given hormone-based contraceptives generally report little change in mood (Masse et al., 1998), or they report an altered pattern of mood changes across the menstrual cycle when women on hormone-based contraceptives were compared to those on non-hormone contraceptives (Abraham et al., 2003). A recent placebo controlled study of adolescents given oral contraceptives showed “improvement” in CES-D scores in both placebo treated and oral contraceptive treated adolescents (O’Connell et al, 2007).

In addition to hormone-based contraceptives that include both an estrogen and progestin component, alternative progestin-only forms of contraception are now in use (e.g., Depo-Provera and the Norplant surgical implant), and studies have examined their relationship to mood. In general, progestin-only forms of contraception are longer acting and thus require less compliance burden than daily oral contraceptive administration. In a large multi-site study, Westhoff et al. (1998a) reported that among women who chose Norplant (n = 910), those who dropped out of the study (n = 93) had higher depression scores than those who continued with Norplant. Among those who stayed in the study, depression scores were unchanged after six months. A similar pattern was observed in women who elected to use Depo-Provera (n = 495) (Westhoff et al., 1998b); the women who dropped out (n = 218) had higher depression scores than those who remained on Depo-Provera. The depression scores of women who remained on Depo-Provera showed minimal change over one year. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of the progestin-only contraceptive norethisterone enanthate in 180 postpartum women found significant increases in the Montgomery Asberg and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scales (Lawrie et al., 1998). Thus, there is some literature suggesting that progestin-only forms of contraceptive may worsen mood in women who are susceptible to depression.

Despite these findings of the effects of hormone-based contraceptives on mood, no studies have examined the effects of these hormonal treatments on the symptoms of major depression. Studies in non-human primates have found that the main estrogen in humans, estradiol, modulates brain serotonin systems at multiple sites including synthesis, reuptake and receptors (Shively et al., 2004). Therefore, synthetic estrogen plus progestin (combined) contraceptives that lead to changes in estrogens could influence brain serotonin systems. Some studies have examined the effects of estradiol on depressed mood in women with altered reproductive hormones such as post-partum depression or depression during the perimenopause and found mood improvements in randomized controlled trials (Gregoire et al, 1996; Schmidt et al, 2000; Soares et al, 2001). However, no beneficial effects of estradiol alone were observed in postmenopausal women with depression (Morrison et al, 2004). These studies utilized estradiol rather than ethinyl estradiol so it is unclear whether similar effects would be observed with combined hormone based contraceptives in normally cycling premenopausal women.

Despite suggestions that hormone-based contraceptives might affect mood, the use of these forms of contraception remain prevalent in reproductive aged women, those who are at the greatest risk for development of depression. The purpose of this study was to examine the association of hormone-based contraceptives with mood in a population of premenopausal women with non-psychotic major depressive disorder (MDD) to determine whether those that use combined hormone contraception, progestin-only contraception, or neither differ in terms of depression severity, function and quality of life, and general medical and psychiatric comorbidity.

METHODS

Overview

This report evaluates a broadly representative clinical sample of outpatients with nonpsychotic MDD enrolled in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial (www.star-d.org). The rationale and design of STAR*D have been detailed elsewhere (Fava et al., 2003; Rush et al., 2004).

Briefly, the aim of STAR*D was to define prospectively which of several treatments are most effective for outpatients with non-psychotic MDD who had an unsatisfactory clinical outcome to an initial and, if necessary, subsequent treatment(s). Eligible and consenting STAR*D enrollees were treated initially (Level 1) with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram. Those who reached remission (defined as a score ≤5 on the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology - Clinician-rated [QIDS-C16] [Rush et al., 2003; Trivedi et al., 2004; Rush et al., 2006]) or response (a >50% decrease from the baseline QIDS-C16 score) could enter a 12-month naturalistic follow-up phase, though non-remitters were advised to enter the subsequent randomized controlled trials which offered a total of four additional possible levels of treatment.

The STAR*D infrastructure included the National Coordinating Center in Dallas, the Data Coordinating Center in Pittsburgh, and 18 primary care and 23 specialty (psychiatric) care clinical settings. The institutional review boards at the National Coordinating Center, the Data Coordinating Center, Regional Centers and Clinical Sites, and the Data Safety Monitoring Board of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; Bethesda, MD) approved and monitored the study protocol.

Clinical Research Coordinators (CRCs) located at the clinical sites were trained and certified in implementing the treatment protocol and in data collection methods (screening, application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, collecting clinical data). Additionally they administered some of the clinician-rated instruments, ensured completion of the self-rated instruments and acted as liaison between the Clinical Sites and the Regional, National and Data Coordinating Centers.

Trained Research Outcomes Assessors (ROAs), who were masked to treatment and were not located at any clinical site, collected outcome data via telephone interviews with participants. Additionally, an automated telephone-based Interactive Voice Response (IVR) system obtained additional outcome data from participants (Kobak et al., 1999).

Study Population

From July 2001 through April 2004, STAR*D enrolled outpatients 18-75 years of age with a diagnosis of nonpsychotic MDD. The present study sample was identified from 4041 consecutive participants enrolled in STAR*D (Fava et al., 2003; Rush et al., 2004). All risks, benefits and adverse events associated with the STAR*D trial were explained to potential participants, who provided written informed consent prior to study participation.

Only self-declared outpatients seeking routine medical or psychiatric treatment were eligible for study participation; recruiting via advertisements was not permitted. Broad inclusion and minimal exclusion criteria were used to ensure a representative sample. Patients with a score ≥14 (moderate intensity) on the CRC-rated 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD17) (Hamilton, 1960; Hamilton, 1967) were eligible. Those with bipolar disorder or psychotic symptoms (lifetime) were excluded, as were those with a current primary diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive or eating disorders, substance abuse/dependence or suicide risk requiring inpatient care, non-response to an adequate treatment trial of any medication used in the first two treatment steps of the protocol during the present episode of MDD, or a seizure disorder or other general medical condition contraindicating medications used in the first two treatment steps. All other psychiatric and general medical comorbidities were allowed. Patients who were pregnant, breast-feeding or planning to conceive in the nine months subsequent to study entry were excluded.

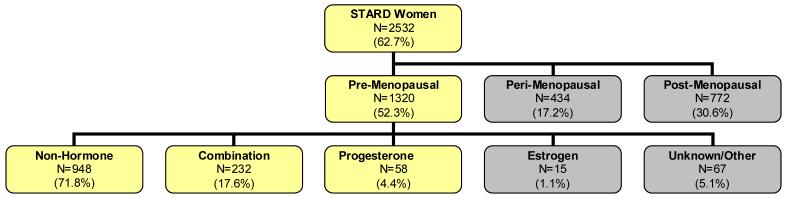

The population for this analysis was comprised of pre-menopausal women (defined as < 40 years of age) on combined hormone contraception (N=232), progestin- only (N=58) or no reproductive hormonal medication (N=948) (Figure 1) using the baseline (pre-treatment) assessments. A medication log was completed at each clinic visit. Study subjects recorded any medication they were taking since the past visit, including the start and end date and the indication. Using this log, medications were classified as to hormone content and type by 4 raters (EAY, SGK and ATH, JB). All 4 individuals had to agree on the classification of the medication or the subject was excluded from analysis.

Figure 1.

Diagram of Study Population demonstrating the distribution of subjects. The total sample of women entering STAR*D was 2532. Of these we excluded all women who were perimenopausal or postmenopausal for a sample size of 1320. Some subjects were excluded because of unclear data or use of other hormones such as androgens or androgen antagonists, which would affect reproductive hormones. The total sample size was 1238. The darkened nodes indicate groups not included in the sample

Assessments

The clinically established diagnosis of non-psychotic MDD was confirmed by a checklist using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th ed. (DSM-IV) criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). At baseline, the CRCs collected standard demographic information, self-reported psychiatric history (including an assessment of suicidality) and severity of depressive symptoms as assessed by the HRSD17 and the QIDS-C16. The CRC administered the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS), a 14-item interviewer-administered scale that gauges the severity/morbidity of general medical conditions (GMCs) relevant to different organ systems (Linn et al., 1968; Miller et al., 1992). The CIRS generates three scores: Categories Endorsed indicates the number of the 14 possible comorbid GMCs endorsed by the participant, Severity Index is the average severity score of the domains endorsed, and Total Severity is the number of categories endorsed multiplied by the average severity.

Additionally, each participant completed the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ) (Zimmerman and Mattia, 1999). This self-report instrument is used to determine the presence of comorbid psychiatric disorders. The total number of symptom items relevant to each disorder is calculated. Then, based on a 90% specificity threshold, the relevant Axis I disorder is declared to be present or absent (Rush et al. submitted).

The ROAs used a telephone interview to collect the HRSD17, as well as the 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS-C30) (Rush et al., 1996; Rush et al., 2000) which uses unconfounded items to measure both core criterion diagnostic symptoms and associated symptoms of depression. The IDS-C30 was used to determine the presence of the atypical (Novic et al, 2005) and melancholic (Kahn et al, 2006) features of depression, and the HRSD17 was used to define the presence of the anxious features of depression (Fava et al, 2004).

A briefer 16-item depression severity scale, the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology - Self-Report (QIDS-SR16) (Trivedi et al., 1992; Rush et al., 2003) was also completed. The QIDS-SR16 rates the nine criterion symptom domains (range 0-27) needed to diagnose a major depressive episode (MDE) by DSM-IV.

The IVR collected health perceptions by the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) (Ware et al., 1996; Sugar et al., 1998), quality of life by the Quality of Life Enjoyment & Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q) (Endicott et al., 1993) which assesses the degree of enjoyment and satisfaction experienced by participants in various areas of daily functioning, and the 5-item Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) (Mundt et al., 2002) which captures the participant’s report of daily function.

Statistical Methods

Comparisons of pre-menopausal women on combined hormone contraception, progesterone-only contraception and no reproductive hormonal contraception were conducted for demographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics, depressive symptoms, and psychiatric co-morbidities. Due to missing data, the sample size varied across comparisons.

Analyses are presented both unadjusted and adjusted for age and years of schooling. The association between discrete variables and hormonal status was first tested using the chi-square test and subsequently adjusted for age and years of schooling (or age, years of schooling, and severity of depression as measured by the IDS-C30 in the case of the depression symptoms) via logistic regression analysis for dichotomous variables and multinomial regression for discrete variables with three or more levels. The association between continuous variables and hormonal status was initially tested using the Kruskal-Wallis procedure, and subsequently adjusted for age and years of schooling by means of a generalized linear modeling procedure.

An association was considered statistically significant at p <0.05. Post-hoc testing was conducted for any association revealed to be significant in the adjusted analysis. A Bonferroni correction was applied to all post-hoc comparisons, with a p <0.0167 indicating a statistically significant pairwise comparison.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the demographic data and the results of comparisons made between the three groups: premenopausal women on combination estrogen and progestin based contraceptives (n=232), those on progestin-only based contraceptives (n=58) and those on no hormonal contraceptives (n=948). The combination hormone group had a significantly larger proportion of Caucasians than either of the other two groups. The combination group also was younger with more years of education. Subsequent analyses were adjusted for age and education due to differences in these factors between the combination group and the other groups.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics: Associations with Hormonal Status

| Demographic Characteristics | Contraception Used |

Unadjusted p-value | Adjusted OR Combo vs. Non-Hormone | Adjusted OR Progestin vs. Non-Hormone | Adjusted p-value* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combo (N=232) | Progestin (N=58) | Non-Hormone (N=948 | |||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | N | % | ||||||||

| Race-Caucasian** | 185 | 79.7 | 40 | 69.0 | 656 | 69.2 | 0.0060 | 1.62 | 0.97 | 0.0290 | |||

| Ethnicity-Hispanic | 28 | 12.1 | 7 | 12.0 | 148 | 15.6 | 0.3277 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 0.7291 | |||

| Employment Status - Employed | 168 | 72.4 | 34 | 58.6 | 589 | 62.3 | 0.0106 | 1.38 | 0.92 | 0.1458 | |||

| Marital Status-Married | 84 | 36.2 | 26 | 44.8 | 366 | 38.7 | 0.4712 | 1.15 | 1.47 | 0.2921 | |||

| Insurance | |||||||||||||

| Private | 144 | 63.7 | 23 | 41.1 | 459 | 50.4 | 0.0014 | 1.41 | 0.77 | 0.0851 | |||

| Public | 21 | 9.3 | 12 | 21.4 | 151 | 16.6 | 0.83 | 1.16 | |||||

| No Insurance | 61 | 27.0 | 21 | 37.5 | 301 | 33.0 | |||||||

| Setting - Primary Care | 74 | 31.9 | 26 | 44.8 | 326 | 34.4 | 0.1792 | 0.93 | 0.61 | 0.1924 | |||

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |||||

| Age | 232 | 26.5 | 5.5 | 58 | 27.4 | 4.9 | 948 | 29.4 | 5.88 | <.0001 | |||

| Education (Yrs of Schooling) | 231 | 14.4 | 2.9 | 58 | 12.7 | 3.1 | 946 | 13.3 | 3.00 | <.0001 | |||

Models were adjusted for age and years of schooling. Post-Hoc comparisons were performed on adjusted models where p < 0.05 (in bold above).

Post-hoc comparisons revealed that participants in the combination hormone group were 1.599 times as likely to be Caucasian relative to participants in the non-hormone group (p=0.0103).

Table 2 shows depression clinical characteristics and severity ratings and their association with contraceptive status, as well as post-hoc comparisons made between groups. The combination hormone group showed significantly less depression severity than the non-hormone group on the HRSD17, IDS-C30 and QIDS-SR16, though only the QIDS-SR16 result was significant after adjustment for age and education. The combination hormone group also demonstrated significantly better overall functioning compared to the non-hormone group on the Q-LES-Q, WSAS and SF12 physical, though only the SF-12 physical comparison remained significant compared to both of the other groups after adjustment. Women on progestin-only-based contraceptives showed higher medical comorbidity on the CIRS but a better mental functioning (SF-12 mental) than either the combination hormone group or the non-hormone group. No differences were seen in depression subtypes (i.e., atypical vs. melancholic vs. anxious) among the three groups.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics: Association with Hormonal Status

| Contraception Used |

Post-Hoc Comparisons** |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combo (N=232) | Progestin (N=58) | Non-Hormone (N=948) | Combo vs. Progesterone | Combo vs. Non-Hormone | Progestin vs. Non-Hormone | ||||||||

| Characteristics | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | p-value | |||

| Age at onset of 1st MDE | 232 | 17.22 | 6.92 | 57 | 18.65 | 7.02 | 933 | 18.96 | 7.94 | 0.0405 | |||

| Age at onset of 1st MDE, Adjusted | 18.10 | 19.36 | 18.68 | 0.4214 | |||||||||

| Number of MDE Episodes | 201 | 3.37 | 3.66 | 51 | 5.78 | 8.55 | 828 | 4.74 | 8.65 | 0.2575 | |||

| Number of MDE Episodes, Adjusted | 3.53 | 5.79 | 4.71 | 0.1013 | |||||||||

| Length of Episode (Months) | 231 | 14.64 | 29.10 | 58 | 18.54 | 38.63 | 937 | 19.74 | 40.40 | 0.2604 | |||

| Length of Episode (Months) , Adjusted | 17.71 | 18.62 | 19.01 | 0.9042 | |||||||||

| CIRS total score | 232 | 2.54 | 2.41 | 58 | 3.98 | 3.06 | 948 | 2.97 | 2.83 | 0.0021 | |||

| CIRS total score, Adjusted | 2.84 | 4.00 | 2.90 | 0.0099 | 0.0017 | 0.797 | 0.0036 | ||||||

| Length of Illness | 232 | 9.36 | 7.92 | 57 | 8.74 | 6.38 | 933 | 10.53 | 8.00 | 0.0469 | |||

| Length of Illness, Adjusted | 10.75 | 9.47 | 10.15 | 0.3957 | |||||||||

| HRSD17 | 217 | 19.51 | 5.90 | 50 | 19.54 | 5.99 | 864 | 20.62 | 6.49 | 0.0237 | |||

| HRSD17, Adjusted | 20.15 | 19.32 | 20.47 | 0.3929 | |||||||||

| IDS-C30 | 214 | 35.35 | 10.37 | 48 | 37.21 | 11.37 | 859 | 37.33 | 11.31 | 0.0479 | |||

| IDS-C30, Adjusted | 36.36 | 36.91 | 37.09 | 0.6978 | |||||||||

| QIDS-SR16 | 232 | 15.01 | 4.18 | 58 | 16.07 | 4.49 | 945 | 16.43 | 4.15 | <.0001 | |||

| QIDS-SR16, Adjusted | 15.11 | 15.98 | 16.40 | 0.0002 | 0.1647 | <.0001 | 0.4462 | ||||||

| SF-12 (Mental) | 218 | 23.91 | 7.66 | 53 | 27.33 | 9.23 | 850 | 24.65 | 8.17 | 0.0487 | |||

| SF-12 (Mental) , Adjusted | 24.13 | 27.27 | 24.61 | 0.0423 | 0.0047 | 0.4633 | 0.0285 | ||||||

| SF-12 (Physical) | 218 | 55.66 | 8.74 | 53 | 50.57 | 11.13 | 850 | 51.97 | 10.36 | <.0001 | |||

| SF-12 (Physical) , Adjusted | 54.45 | 50.86 | 52.25 | 0.0072 | 0.0044 | 0.0049 | 0.3539 | ||||||

| WSAS | 218 | 21.81 | 8.67 | 53 | 22.47 | 9.58 | 850 | 24.08 | 9.27 | 0.0014 | |||

| WSAS, Adjusted | 22.35 | 22.49 | 23.95 | 0.0560 | |||||||||

| QLESQ | 218 | 44.22 | 13.64 | 53 | 43.72 | 15.43 | 850 | 40.69 | 15.08 | 0.0081 | |||

| QLESQ, Adjusted | 43.11 | 43.72 | 40.96 | 0.0940 | |||||||||

| Combo (N=232) | Progestin (N=58) | Non-Hormone (N=948) | |||||||||||

| N | % | n | % | n | % | Unadjusted p-value | Adjusted OR Combo vs. Non Hormone | Adjusted OR Progestin vs. Non-Hormone | Adjusted p-value | ||||

| Family History of Depression | 148 | 64.3 | 31 | 53.5 | 544 | 58.0 | 0.1460 | 1.28 | 0.83 | 0.1920 | |||

| Attempted Suicide | 49 | 21.1 | 12 | 20.7 | 217 | 22.9 | 0.8008 | 0.99 | 0.80 | 0.8128 | |||

| Chronic Depression | 37 | 16.9 | 11 | 19.0 | 192 | 20.5 | 0.3057 | 0.88 | 0.95 | 0.8190 | |||

| Recurrent Depression | 158 | 73.5 | 663 | 75.1 | 41 | 75.9 | 0.8736 | 0.88 | 1.07 | 0.7275 | |||

| Age of Onset | 102 | 44.0 | 25 | 43.9 | 464 | 49.7 | 0.2277 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.7975 | |||

| Anxious Features | 90 | 41.3 | 21 | 40.4 | 420 | 48.3 | 0.1186 | 0.98 | 0.70 | 0.4896 | |||

| Atypical Features | 42 | 19.3 | 15 | 28.9 | 178 | 20.5 | |||||||

| Melancholic Features | 40 | 18.4 | 6 | 11.5 | 194 | 22.3 | 0.1049 | 0.84 | 0.45 | 0.1559 | |||

Model adjusted for age and years of schooling.

Post-Hoc comparisons were performed for adjusted models where p < 0.05.

MDE: Major Depressive Episode, CIRS: Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, HRSD17: 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, IDS-C30: 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, QIDSSR16: 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, SF-12: 12-item Short Form Health Survey, WSAS: Work and Social Adjustment Scale, Q-LES-Q: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire

The presence of depressive symptoms by contraceptive status and comparisons between groups are shown in Table 3. Women in both hormone groups were more likely to show hypersomnia compared to the non-hormone group. Women in the progestin-only group were significantly more likely to show increased appetite, weight gain and gastrointestinal symptoms than those in the non-hormone group. Adjustment did not affect the findings for weight gain or gastrointestinal symptoms though the significant findings for appetite increase were lost after adjustment. Comorbid psychiatric disorders, as measured by the PDSQ are shown in Table 4. Women in the combination group were less likely to show obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) comorbidities than women in the non-hormone group and were less likely to show panic disorder compared to the progestin-only group. After adjustment, only the OCD result remained significant, with the combination group less likely to show OCD than the non-hormone or progestin-only groups.

Table 3.

Baseline IDS-C30 (ROA): Hormonal Status

| Combo (N=232) | Progesterone (N=58) | Non-Hormone (N=948) | adj OR combo v. non-hormone | adj OR prog v. non-hormone | adj* p-value | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent | Present | Absent | Present | Absent | Present | ||||||||||||

| IDS-C30 (ROA) items | N | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | N | % | p-value | |||

| Sleep Onset Insomnia | 1140 | 71 | 32.6 | 147 | 67.4 | 18 | 34.6 | 34 | 65.4 | 251 | 28.9 | 619 | 71.1 | 0.4171 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.4192 |

| Mid-Nocturnal Insomnia | 1139 | 48 | 22.0 | 170 | 78.0 | 10 | 19.2 | 42 | 80.8 | 184 | 21.2 | 685 | 78.8 | 0.9018 | 1.30 | 1.33 | 0.3765 |

| Early Morning Insomnia | 1141 | 113 | 51.8 | 105 | 48.2 | 26 | 50.0 | 26 | 50.0 | 460 | 52.8 | 411 | 47.2 | 0.9034 | 1.44 | 1.13 | 0.1063 |

| Hypersomnia | 1139 | 133 | 61.3 | 84 | 38.7 | 31 | 60.8 | 20 | 39.2 | 646 | 74.2 | 225 | 25.8 | 0.0002 | 1.42 | 1.69 | 0.0387 |

| Mood-Sad | 1141 | 5 | 2.3 | 213 | 97.7 | 1 | 1.9 | 51 | 98.2 | 15 | 1.7 | 856 | 98.3 | 0.7072 | 0.51 | 1.61 | 0.5435 |

| Mood-Irritable | 1141 | 28 | 12.8 | 190 | 87.2 | 6 | 11.5 | 46 | 88.5 | 103 | 11.8 | 768 | 88.2 | 0.9128 | 1.13 | 0.88 | 0.8462 |

| Mood-Anxious | 1141 | 49 | 22.5 | 169 | 77.5 | 10 | 19.2 | 42 | 80.8 | 149 | 17.1 | 722 | 82.9 | 0.1818 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.2837 |

| Reactivity of Mood | 1140 | 52 | 23.9 | 166 | 76.1 | 15 | 28.9 | 37 | 71.2 | 223 | 25.6 | 647 | 74.4 | 0.7318 | 1.32 | 0.80 | 0.2831 |

| Mood Variation | 1140 | 165 | 76.0 | 52 | 24.0 | 37 | 71.1 | 15 | 28.9 | 664 | 76.2 | 207 | 23.8 | 0.7067 | 1.05 | 1.43 | 0.5455 |

| Quality of Mood | 1141 | 56 | 25.7 | 162 | 74.3 | 15 | 28.9 | 37 | 71.2 | 214 | 24.6 | 657 | 75.4 | 0.7590 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 0.7114 |

| Appetite-Decreased | 1138 | 116 | 53.2 | 102 | 46.8 | 32 | 61.5 | 20 | 38.5 | 417 | 48.0 | 451 | 52.0 | 0.0844 | 0.92 | 0.54 | 0.1377 |

| Appetite-Increased | 1138 | 166 | 76.1 | 52 | 23.9 | 32 | 61.5 | 20 | 38.5 | 666 | 76.7 | 202 | 23.3 | 0.0451 | 0.95 | 2.07 | 0.0568 |

| Weight-Decrease | 1140 | 157 | 72.0 | 61 | 28.0 | 36 | 70.6 | 15 | 29.4 | 583 | 66.9 | 288 | 33.1 | 0.3281 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.6086 |

| Weight-Increase | 1140 | 171 | 78.4 | 47 | 21.6 | 29 | 56.9 | 22 | 43.1 | 652 | 74.9 | 219 | 25.1 | 0.0060 | 0.84 | 2.44 | 0.0073 |

| Concentration/Decision Making | 1141 | 16 | 7.3 | 202 | 92.7 | 6 | 11.5 | 46 | 88.5 | 75 | 8.6 | 796 | 91.4 | 0.6040 | 1.23 | 0.70 | 0.6066 |

| Outlook-Self | 1139 | 29 | 13.3 | 189 | 86.7 | 8 | 15.4 | 44 | 84.6 | 114 | 13.1 | 755 | 86.9 | 0.8960 | 0.87 | 0.68 | 0.6204 |

| Outlook-Future | 1137 | 51 | 23.5 | 166 | 76.5 | 16 | 30.8 | 36 | 69.2 | 189 | 21.8 | 679 | 78.2 | 0.2974 | 0.92 | 0.56 | 0.2486 |

| Suicidal Ideation | 1141 | 126 | 57.8 | 92 | 42.2 | 33 | 63.5 | 19 | 36.5 | 466 | 53.5 | 405 | 46.5 | 0.2278 | 0.97 | 0.53 | 0.1818 |

| Involvement | 1141 | 34 | 15.6 | 184 | 84.4 | 9 | 17.3 | 43 | 82.7 | 91 | 10.5 | 780 | 89.5 | 0.0477 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.0403 |

| Energy/Fatigability | 1141 | 8 | 3.7 | 210 | 96.3 | 6 | 11.5 | 46 | 88.5 | 62 | 7.1 | 809 | 92.9 | 0.0665 | 2.52 | 0.93 | 0.0956 |

| Pleasure/Enjoyment | 1141 | 67 | 30.7 | 151 | 69.3 | 19 | 36.5 | 33 | 63.5 | 226 | 25.9 | 645 | 74.1 | 0.1148 | 0.94 | 0.49 | 0.1335 |

| Sexual Interest | 1141 | 68 | 31.2 | 150 | 68.8 | 12 | 23.1 | 40 | 76.9 | 287 | 32.9 | 584 | 67.1 | 0.3152 | 1.46 | 1.83 | 0.0491 |

| Psychomotor Slowing | 1141 | 90 | 41.3 | 128 | 58.7 | 21 | 40.4 | 31 | 59.6 | 330 | 37.9 | 541 | 62.1 | 0.6320 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.9325 |

| Psychomotor Agitation | 1140 | 87 | 39.9 | 131 | 60.1 | 22 | 42.3 | 30 | 57.7 | 313 | 36.0 | 557 | 64.0 | 0.4046 | 0.79 | 0.60 | 0.1437 |

| Somatic (pain) Complaints | 1141 | 52 | 23.9 | 166 | 76.1 | 11 | 21.2 | 41 | 78.9 | 183 | 21.0 | 688 | 79.0 | 0.6575 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 0.9558 |

| Sympathetic Arousal | 1140 | 86 | 39.5 | 132 | 60.5 | 19 | 36.5 | 33 | 63.5 | 298 | 34.3 | 572 | 65.7 | 0.3511 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.8706 |

| Panic/Phobic Symptoms | 1136 | 145 | 66.8 | 72 | 33.2 | 28 | 57.1 | 21 | 42.9 | 522 | 60.0 | 348 | 40.0 | 0.1531 | 0.80 | 1.09 | 0.4417 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1141 | 121 | 55.5 | 97 | 44.5 | 24 | 46.1 | 28 | 53.9 | 522 | 59.9 | 349 | 40.1 | 0.0906 | 1.61 | 2.09 | 0.0023 |

| Interpersonal Sensitivity | 1141 | 56 | 25.7 | 162 | 74.3 | 18 | 34.6 | 34 | 65.4 | 275 | 31.6 | 596 | 68.4 | 0.1959 | 1.26 | 0.89 | 0.4249 |

| Leaden Paralysis/Physical Energy | 1141 | 127 | 58.3 | 91 | 41.7 | 26 | 50.0 | 26 | 50.0 | 501 | 57.5 | 370 | 42.5 | 0.5403 | 1.18 | 1.63 | 0.2345 |

Models were adjusted for age, years of schooling and IDS total score at baseline. Post-Hoc comparisons were performed on adjusted models where p < 0.05 (in bold above).

Post-Hoc comparisons revealed that patients in the combination group were 0.34 times as likely to have weight increase relative to those in the progesterone group (p=0.0026), and patients in the progesterone group were 2.4 times as likely to have weight increase relative to those in the non-hormone group (p=0.0048). Regarding gastrointestinal symptoms, patients in the combination group were 1.6 times as likely to develop symptoms relative to the non-hormone group (p=0.0045).

Table 4.

Psychiatric Co-Morbidities (PDSQ): Associations with Contraception Status

| Psychiatric Comorbidities Present | Contraception Used | Unadjusted p-value | Adjusted OR Combo vs. Non-Hormone | Adjusted OR Progestin vs. Non-Hormone | Adjusted* p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combo (N=232) | Progestin (N=58) | Non-Hormone (N=948) | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

| OCD** | 17 | 7.4 | 8 | 14.0 | 155 | 16.5 | 0.0020 | 0.44 | 0.78 | 0.0111 |

| Panic | 25 | 10.8 | 14 | 24.6 | 138 | 14.7 | 0.0270 | 0.79 | 1.83 | 0.0875 |

| Social Phobia | 78 | 33.8 | 19 | 33.3 | 352 | 37.6 | 0.4876 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.2869 |

| PTSD | 30 | 13.0 | 10 | 17.5 | 202 | 21.5 | 0.0135 | 0.64 | 0.79 | 0.1071 |

| Agoraphobia | 17 | 7.4 | 6 | 10.5 | 113 | 12.1 | 0.1244 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.3849 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 16 | 6.9 | 7 | 12.3 | 88 | 9.4 | 0.3497 | 0.77 | 1.29 | 0.5260 |

| Drug abuse | 13 | 5.6 | 5 | 8.8 | 73 | 7.8 | 0.4956 | 0.69 | 0.97 | 0.4990 |

| Somatoform | 4 | 1.7 | 3 | 5.3 | 29 | 3.1 | 0.3108 | 0.75 | 1.73 | 0.5628 |

| Hypochondriasis | 5 | 2.2 | 2 | 3.5 | 48 | 5.1 | 0.1435 | 0.54 | 0.63 | 0.3805 |

| Bulimia | 38 | 16.5 | 9 | 15.8 | 181 | 19.2 | 0.5343 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.3436 |

| GAD | 45 | 19.5 | 14 | 24.6 | 261 | 27.8 | 0.0340 | 0.71 | 0.84 | 0.1759 |

Models were adjusted for age and years of schooling. Post-Hoc comparisons were performed on adjusted models where p < 0.05 (in bold above).

Post-Hoc comparisons revealed that participants in the combination hormone group were 0.441 times as likely to have OCD relative to participants in the non-hormone group (p-value=0.0027).

PDSQ: Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire, OCD: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, PTSD: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder GAD: General Anxiety Disorder

DISCUSSION

Hormone-based contraceptives are commonly used by women of reproductive age, the age in which recurrent depressive episodes are commonly seen. The large number of participants enrolled into STAR*D enabled us to examine whether there are any systematic differences among premenopausal depressed women using combination hormone-based contraceptives, those using progestin-only based contraceptives (primarily depot Provera or Norplant) and those not taking exogenous reproductive hormones. The data suggest several findings that were expected and one finding that was surprising. Overall, compared to the non-hormone group, women on combination hormone contraception showed less severity of depression, better physical functioning on the SF-12 and fewer comorbid anxiety disorders based on the PDSQ (Table 4), though only the OCD result remained significant after adjustment. However, women on combination hormone contraception showed lower mental function on the SF-12, which is hard to explain given the lesser severity of depression. The combination hormone group also demonstrated better physical functioning compared to the progestin-only group. These findings persisted after correction for age and educational level, which suggests that this may be related to a pharmacological effect of ethinyl estradiol. Basic studies in animals have found that estrogen is an important modulator of brain serotonin systems and that estrogen reduces anxiety in females in a number of anxiety-related tests (Young et al., 2002). Our data are consistent with the possibility that estrogen-containing contraceptives might have similar effects in depressed women. A greater incidence of hypersomnia was observed in the combined group, which could be related to the progestins which can induce drowsiness in some women (Rupprecht, 2003) in contrast to estrogen that has central nervous system activating effects (Devidze et al, 2006).

The progestin-only group showed more general medical comorbidity and worse physical functioning on the SF-12 than the combined and non-hormone groups. However, the progestin only group showed better mental functioning on the SF-12 compared to either no hormone group or the combined hormone group. The latter finding is hard to interpret based upon known effects of progestins. The progestin-only group also showed increased appetite (unadjusted result) and weight gain. Both Depot-Provera and Norplant list weight gain as a side effect. Consequently, it is not clear if the increased appetite and weight gain are symptoms of depression or secondary to progestin use but the data suggest that the weight gain is secondary to progestins rather than depression. It is also unclear if progestins unopposed by estrogen worsened some pre-existing medical comorbidities or if women with medical illnesses were more likely to be prescribed progestin-only-based contraceptives.

This study had a number of limitations. First, we do not know the relationship, if any, between use of these contraceptive agents and the depressive symptoms. Similar to other reports, it is likely that women who remained on these forms of contraception were those who tolerated them the best, but we collected no data to make this determination. Furthermore, we do not know the reason women were taking these medications. It is possible some women were prescribed these hormones for mood changes. Although we measured several demographic characteristics, other factors that were not measured including smoking history, history of migraine, religious belief, risks for deep venous thrombosis, past history of high blood pressure, or an abusive partner could impact on whether a woman requests and/or is prescribed ongoing oral contraception. These same variables also could impact on the outcome measures employed in this study. Second, we had a small sample size in the progestin-only group. Nonetheless, we examined this group as progestin has been reported to cause mood disturbances. Data on this group are clearly subject to type II errors due to small sample size. Third, a large number of demographic and symptom variables were analyzed, and no correction was made for multiple tests other than in the post-hoc comparison. Thus, the nature of the analyses was clearly exploratory. Despite the exploratory nature of the analysis, the findings fit with other data that have examined the effects of hormone-based contraceptive treatments in general samples of women (i.e., increased sleep and increased appetite). Finally, the findings of higher educational levels in women using combined hormone treatments, which parallels the findings in naturalistic hormone replacement studies, may still influence some of the observed differences. Other differences found among the groups like race and insurance status may have additionally contributed to the findings since this is a naturalistic study and other unmeasured variables may have influenced which women were or were not using hormone based contraceptives.

In summary, our data suggest that women receiving combination hormone-based contraceptives showed less severe depressive symptoms, better overall physical function and a decreased number of comorbid anxiety disorders, findings that may be linked to beneficial effects of ethinyl estradiol. Future prospective studies are needed to determine whether estrogens might improve some aspects of overall functioning in depressed women. Women with major depression who take progestin-only contraception may experience changes in GI symptoms such as overeating and weight gain that influence depressive symptom profiles. Finally, overall effects of hormone based contraception on mood were small and there is no evidence any of these hormone treatments worsened depressive symptoms.

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded with Federal funds from the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, under Contract N01MH90003 to UT Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas (P.I.: A.J. Rush).

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

We appreciate the support of Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, King Pharmaceuticals, Organon Inc., Pfizer Inc., and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories in providing medications at no cost for this trial.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth A Young, Department of Psychiatry and Molecular and Behavioral Neurosciences Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor MI 48109-0720.

Susan G Kornstein, Department of Psychiatry and Obstetrics and Gynecology, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, PO Box 980710, Richmond, VA 23298-0710.

Anne T Harvey, Via Christi Research, Inc. 1100 N. St. Francis, Suite 300 Wichita, KS 67214.

Stephen R. Wisniewski, Epidemiology Data Center, GSPH, University of Pittsburgh, 127 Parran Hall, 130 DeSoto Street, Pittsburgh PA,15261

Jennifer Barkin, Epidemiology Data Center, GSPH, University of Pittsburgh, 127 Parran Hall, 130 DeSoto Street, Pittsburgh PA,15261.

Maurizio Fava, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street-Bulfinch 351, Boston MA 02114.

Madhukar H Trivedi, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, 6363 Forest Park Road, Suite 13.354, Dallas TX 75235.

A John Rush, Departments of Clinical Sciences and Psychiatry, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard Dallas TX 75390-9066.

REFERENCES

- Abraham S, Luscombe G, Soo I. Oral contraception and cyclic changes in premenstrual and menstrual experiences. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2003;24:185–193. doi: 10.3109/01674820309039672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) American Psychiatric Association Press, Inc; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: A new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993:29321–29326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devidze N, Lee AW, Zhou J, Pfaff DW. CNS arousal mechanisms bearing on sex and other biologically regulated behaviors. Physiol Behav. 2006;88:283–93. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Alpert JE, Carmin CN, Wisniewski SR, Trivedi MH, Biggs MM, Shores-Wilson K, Morgan D, Schwartz T, Balasubrmanai GK, Rush AJ. Clinical correlates and symptom patterns of anxious depression among patients with major depressive disorder in STAR*D. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:1299–1308. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Sackeim HA, Quitkin FM, Wisniewski S, Lavori PW, Rosenbaum JF, Kupfer DJ. Background and rationale for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2003;26:457–494. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire AJ, Kumar R, Everitt B, Henderson AF, Studd JW. Transdermal oestrogen for treatment of severe postnatal depression. Lancet. 1996;347:930–933. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg BN, Johnson AL, Brown S. Depressive symptoms and oral contraceptives. Br Med J. 1970;4:142–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5728.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe H, Cohen LS, Harlow BL. Impact of oral contraceptive pill use on premenstrual mood: predictors of improvement and deterioration. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;189:1523–1528. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(03)00927-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AY, Carrithers J, Preskorn SH, Wisniewski SR, Lear R, Rush AJ, Stegman D, Kelley C, Kreiner K, Nierenberg AA, Fava M. Clinical and Demographic Factors Associated With DSM-IV Melancholic Depression. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;18:91–98. doi: 10.1080/10401230600614496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Mundt JC, Katzelnick DJ. Computerized assessment of depression and anxiety over the telephone using interactive voice response. MD Computing. 1999;16:64, 14–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie TA, Hofmeyr GJ, De Jager M, Berk M, Paiker J, Viljoen E. A double-blind randomised placebo controlled trial of postnatal norethisterone enanthate: the effect on postnatal depression and serum hormones. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1998;105:1082–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1968;16:622–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masse PG, Van den Berg H, Livingstone MM, Duguay C, Beaulieu G. Nutritional and psychological status of young women after a short-term use of a triphasic contraceptive steroid preparation. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 1998;68:203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Stack JA, Rifai AH, Mulsant B, Reynolds CF., III Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1992;41:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison MF, Kallan MJ, Ten Have T, Katz I, Tweedy K, Battistini M. Lack of efficacy of estradiol for depression in postmenopausal women: a randomized, controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:406–1. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt JC, Mareks IM, Shear K, Greist JH. The work and social adjustment scale (WSAS): a simple accurate measure of impairment in functioning. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180:461–464. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilson A, Almgren PE. Psychiatric symptoms during the post-partum period as related to oral contraceptives. Br Med J. 1968;2:453–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5603.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick JS, Stewart JW, Wisniewski SR, Cook IA, Manev R, Nierenberg A, Rosenbaum J, Shores-Wilson K, Balasubramani GK, Biggs MM, Sizook S, Rush AJ, STAR*D Investigators Clinical and Demographic Features of Atypical Depression in Outpatients with Major Depression: Preliminary Findings from STAR*D. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:1002–1011. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell K, Davis JR, Kerns J. Oral contraceptives: side effects and depression in adolescent girls. Contraception. 2007;75:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oinonen KA, Mazmanian D. To what extent do oral contraceptives influence mood and affect? J. Affect. Disord. 2002;70:229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupprecht R. Neuroactive steroids: mechanisms of action and neuropsychopharmacological properties. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:139–168. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Bernstein IH, Trivedi MH, Carmody TJ, Wisniewski S, Mundt JC, Shores-Wilson K, Biggs MM, Woo A, Nierenberg AA, Fava M. An evaluation of the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: a Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression trial report. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59:493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Carmody T, Reimitz PE. The inventory of depressive symptomatology (IDS): clinician (IDS-C) and self-report (IDS-SR) ratings of depressive symptoms. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2000;9:45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, Trivedi MH. The inventory of depressive symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychological Medicine. 1996;26:477–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, Markowitz JC, Ninan PT, Kornstein S, Manber R, Thase ME, Kocsis JH, Keller MB. The 16-item inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biologic Psychiatry. 2003;54:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Lavori PW, Trivedi M, Sackeim HA, Thase ME, Nierenberg AA, Quitkin KM, Kashner TM, Kupfer DJ, Rosenbaum JF, Alpert J, Stewart J, McGrath PJ, Big MM, Shores-Wilson K, O’Neal BL, Lebowitz RD, Ritz AL, Niederehe G, STAR*D Investigators Group Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D): Rationale and design. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2004;25:118–141. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt PJ, Nieman L, Danaceau MA, Tobin MB, Roca CA, Murphy JH, Rubinow DR. Estrogen replacement in perimenopause-related depression: a preliminary report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:414–420. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shively CA, Bethea CL. Cognition, mood disorders, and sex hormones. ILAR J. 2004;45:189–199. doi: 10.1093/ilar.45.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares CN, Almeida OP, Joffe H, Cohen LS. Efficacy of estradiol for the treatment of depressive disorders in perimenopausal women: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2001;58:529–534. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugar CA, Sturm R, Lee TT, et al. Empirically defined health states for depression from the SF-12. Health Serv. Res. 1998;33(4 Pt 1):911–928. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Biggs MM, Suppes T, Crismon ML, Shores-Wilson K, Toprac MG, Dennehy EB, Witte B, Kashner TM. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:73–82. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr, Kosinksi M, Keller S. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westhoff C, Truman C, Kalmuss D, Cushman L, Davidson A, Rulin M, Heartwell S. Depressive symptoms and Depo-Provera. Contraception. 1998b;57:237–240. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(98)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westhoff C, Truman C, Kalmuss D, Cushman L, Rulin M, Heartwell S, Davidson A. Depressive symptoms and Norplant contraceptive implants. Contraception. 1998a;57:241–245. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(98)00022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsley A, Change A. Oral Contraceptive and emotional states. J Psychosom Res. 1978;22:13–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(78)90085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EA, Korszun A, Altemus M. Sex differences in Neuroendocrine and Neurotransmitter Systems. In: Susan Kornstein, Anita Clayton., editors. Women’s Mental Health, A Comprehensive Textbook. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. The reliability and validity of a screening questionnaire for 13 DSM-IV Axis I disorders (the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire) in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;60:677–683. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]