Abstract

Many G protein α subunits are dually acylated with myristate and palmitate or are palmitoylated on more than one cysteine residue near their N termini. The Gα protein that activates adenylyl cyclase, αs, is not myristoylated but can be reversibly palmitoylated. It appears that αs contains another, as-yet-unidentified covalent modification that decreases its apparent dissociation constant for adenylyl cyclase from 50 nM to <0.5 nM. This modification is at or near the N terminus of the protein and is hydrophobic. Palmitoylation of native αs does not account for its high affinity for adenylyl cyclase.

Heterotrimeric G proteins play a pivotal role in cellular signaling, functioning as molecular switches that couple a diverse array of extracellularly oriented receptors to a variety of intracellular effectors or signal generators. The guanine nucleotide-binding α subunits of G proteins are covalently modified with lipid at or near their N termini (1–3). Thus, members of the αi subfamily contain amide-linked myristate on N-terminal glycine residues, and all α subunits (except αt) contain palmitate in thioester linkage on one or more nearby cysteine residues. Crystal structures of G protein oligomers demonstrate that the N terminus of α is in close proximity to the C terminus of the γ subunit, which is prenylated (4, 5). Thus, the hydrophobic modifications of G protein subunits are gathered together at a point that is assumed to represent one site of interaction of the oligomer with the inner face of the plasma membrane.

Myristoylation is a stable protein modification with substantial functional consequences. Prevention of myristoylation by mutation of Gly2 to Ala in αi proteins causes accumulation in the cytosol of protein expressed in vivo (6, 7). Biochemical characterization of αi1 and/or αo synthesized in bacteria in the presence or absence of myristoyl CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase demonstrates that myristoylated αi proteins have a higher affinity for both the G protein βγ subunit complex and at least one effector, adenylyl cyclase, compared with their nonmyristoylated counterparts (8, 9).

Palmitoylation is a dynamic protein modification. In the case of αs (palmitoylated on Cys3; not myristoylated), activation of cognate receptors (e.g., β-adrenergic receptors) facilitates incorporation of [3H]palmitate into the protein, apparently by stimulating depalmitoylation and thus turnover of the lipid (10, 11). Similar regulation of palmitoylation of other G protein α subunits is often assumed but has not yet been reported. The functional consequences of palmitoylation of α subunits are unclear, and there are inconsistencies in the literature. We (10) and Degtyarev et al. (12) failed to find αs in cytosolic cellular fractions after expression of the Cys3 → Ala mutant of the protein or following activation of the native protein by means of the β-adrenergic receptor. By contrast, others have noted both substantial distribution of Ala3-αs to the cytosol and appearance of the wild-type protein in soluble fractions after activation of receptors (13–15). Although the reasons for these discrepancies have been sought, they have not been found. We and others found that expression of the Cys3 → Ala mutant of αo caused the partial appearance of the protein in the cytosol (10, 16, 17), while modification of both palmitoylated cysteine residues of αq had no effect on cellular distribution (18). Patterns are difficult to perceive.

Comparison of the functional properties of recombinant αs synthesized in bacteria with those of the protein purified from liver or brain has revealed major differences (19). In particular, the apparent affinity of recombinant αs for its effector, adenylyl cyclase, is substantially lower. We have attempted to evaluate the role of palmitoylation or another, unknown, modification of αs in this phenomenon.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Plasmids.

A cDNA encoding bovine αs-short was used to generate hexahistidine-modified (C terminus) αs (αs-CH6), using GCGCTTAAGCTTTTTAGTGATGGTGGTGGTGATGTCCTCCGAGCAGCTCATAC as the mutagenic oligonucleotide. A cDNA encoding an αs-long subunit that has the alternatively spliced sequence contained in exon 3 partially replaced by a hexahistidine tag (αs-H6) was kindly provided by Maurine Linder (Washington University).

Protein Purification.

Wild-type and His6-tagged αs were purified as described after expression in Escherichia coli (20). His6-tagged αs proteins were also expressed in Sf9 cells by infection with recombinant baculoviruses for 40–48 hr. After extraction of Sf9 cell membranes with buffer A [20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0/1 mM GDP/10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol/0.5% polyoxyethylene 10-lauryl ether (C12E10) containing protease inhibitors (21)], NaCl was added (200 mM) and the solution was applied to a column containing Ni2+-NTA (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA; NTA is nitrilotriacetate). The column was washed sequentially with buffer A containing 500 mM NaCl and buffer A containing 200 mM NaCl prior to elution with buffer A containing 150 mM imidazole. The eluate was concentrated, diluted 10-fold, and applied to βγ-agarose (22). Bound protein was eluted with a solution of 20 mM NaHepes (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaCl, 3 mM dithiothreitol, 30 μM AlCl3, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaF, and 0.5% sodium cholate (at room temperature). Protein was concentrated and buffer was exchanged into 20 mM NaHepes, pH 8.0/1 mM EDTA/3 mM dithiothreitol/0.3% sodium cholate. Wild-type αs expressed in Sf9 cells was purified on a β2-His6γ2-Ni2+-NTA column as described (23), except that the membranes were extracted with 0.5% C12E10 and 30% (vol/vol) ethylene glycol was added to the extract. The eluate was further purified on βγ-agarose as described above; binding was achieved by chelation of Mg2+. Native αs was purified from rabbit liver as described (24). The G protein β1γ2 subunit complex was purified after expression in Sf9 cells (23).

Purified αs was activated with guanosine 5′-[γ-thio]triphosphate (GTP[γS]) (19, 25), followed by gel filtration into 50 mM NaHepes, pH 8.0/1 mM EDTA/2 mM MgCl2/100 mM NaCl. The concentration of activated αs was determined by inclusion of radiolabeled GTP[γS] during activation.

Adenylyl Cyclase and GTPase Activities.

Membranes were prepared from Sf9 cells infected with baculovirus encoding type V adenylyl cyclase (26). These membranes (5 μg) were incubated for 3 min at 30°C with activated αs prior to assay of adenylyl cyclase activity for 10 min at 30°C (27). Steady-state GTPase activities of αs proteins were measured as described (28).

Mass Spectrometry.

Molecular masses of certain proteins of interest were determined by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry after protein purification by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography. We are grateful to Clive Slaughter (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) for these determinations.

Miscellaneous Procedures.

Metabolic radiolabeling with [3H]palmitate, immunoblotting, and fluorography were performed as described previously (10).

RESULTS

Activation of Adenylyl Cyclase.

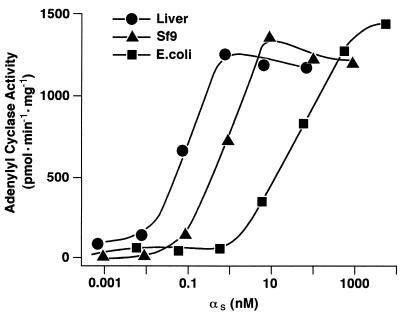

When expressed in E. coli and purified, αs (native sequence, untagged) is capable of activating membrane-bound type V adenylyl cyclase dramatically, but with an apparent affinity (EC50) of only 50 nM (Fig. 1 and ref. 19). By contrast, the protein purified from rabbit liver activates adenylyl cyclase to the same maximal extent but with an EC50 of roughly 0.1 nM (Fig. 1 and ref. 19). A similar discrepancy was observed with detergent-solubilized adenylyl cyclase (19). This suggests the existence of a covalent modification of native αs that facilitates interaction of the protein with the membrane (or detergent micelles) or that enhances the affinity of the requisite interaction between αs and adenylyl cyclase. It is also possible that the conformation of recombinant αs differs from that of the native molecule.

Figure 1.

Activation of adenylyl cyclase. αs was purified from rabbit liver membranes (•) or after expression in Sf9 cells (▴) or E. coli (▪). The proteins were activated with GTP[γS] and reconstituted with membranes (5 μg) from Sf9 cells expressing type V adenylyl cyclase. Adenylyl cyclase activity was assayed as described. Values shown are the average of triplicate determinations and are representative of at least two experiments.

We have attempted to express αs in other heterologous systems that would permit the putative covalent modification, analysis by mutagenesis, and procurement of quantities of protein sufficient for more extensive characterization. To facilitate purification, hexahistidine tags were inserted in one of three locations: the N terminus (H6-αs), the site in exon 3 where splice variants of αs are produced (αs-H6), or the C terminus (αs-CH6). The latter protein was expressed in E. coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Sf9 cells (αs-CH6Sf9) and purified by a combination of Ni2+-NTA and βγ subunit-affinity chromatography. The EC50 values for activation of adenylyl cyclase by these three proteins were approximately 50 nM, 3 nM, and 3 nM, while the yields for the yeast and Sf9 cell preparations were both low—1 μg and 50 μg per liter of culture, respectively. Wild-type αs purified from Sf9 cells was modestly more potent than the corresponding preparation of αs-CH6Sf9 (EC50 ≈ 1 nM; Fig. 1), but the yield was poor because of less efficient purification (5 μg/liter).

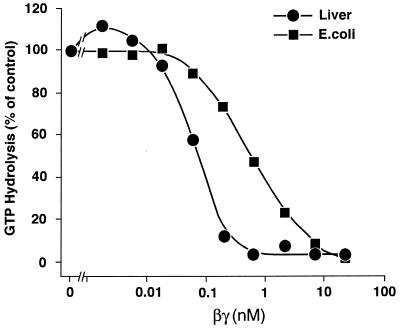

Interaction with βγ.

The affinity of G protein α subunits for the βγ subunit complex can be estimated by virtue of the capacity of βγ to slow dissociation of GDP from α and thus inhibit its steady-state GTPase activity. Such measurements are shown in Fig. 2. To be accurate, the assay must be performed at concentrations of αs below the Kd for its interaction with βγ. However, GTPase activity cannot be assessed reliably at αs concentrations much below 0.4 nM, limiting the range of the measurement. Addition of βγ to native αs resulted in a steep inhibition curve with complete suppression of GTPase activity at roughly equimolar concentrations of αs and βγ. The experiment is thus a titration, and the half-maximally effective concentration of βγ, ≈0.1 nM, is an overestimate of the Kd for the interaction between αs and βγ. By contrast, the EC50 for inhibition of the GTPase activity of E. coli-derived αs by βγ was 0.5 nM, reflecting a substantially reduced affinity of βγ for the recombinant protein.

Figure 2.

Inhibitory effect of β1γ2 on steady-state GTP hydrolysis by αs. Purified αs from rabbit liver (•, 0.39 nM) or recombinant αs synthesized in E. coli (▪, 0.5 nM) was mixed with the indicated concentrations of β1γ2 and then assayed for GTPase activity (20 min, 30°C). Rates of GTP hydrolysis in the absence of β1γ2 were 0.12 and 0.25 pmol/pmol of αs per min for the rabbit liver and recombinant protein, respectively.

Location of the Putative Modification.

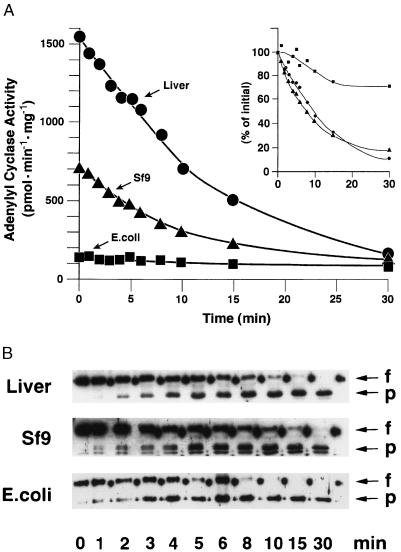

Limited tryptic proteolysis of GTP[γS]-bound α subunits removes a roughly 3-kDa peptide from the N terminus, leaving the rest of the protein largely intact. However, immunoblotting with an antibody that recognizes the C terminus of αs indicated that a few amino acid residues are also removed at this site. Exclusive N-terminal cleavage was achieved with the endoprotease LysC. We have shown previously that such limited proteolysis of E. coli-derived αs alters neither its capacity to activate adenylyl cyclase nor its apparent affinity for the enzyme (26) (Fig. 3A). However, proteolysis of native αs and αs-CH6Sf9 dramatically impaired, but did not eliminate, their stimulatory effect on adenylyl cyclase when tested at a fixed, submaximal concentration, presumably reflecting a decrease in the affinity of N-terminally truncated αs for adenylyl cyclase (Fig. 3A). (Limited quantities of material were available, particularly of the native enzyme, precluding testing over a broad range of concentrations.) The loss of activity of the native and Sf9-derived αs paralleled the loss of the N terminus (Fig. 3B). When full-length protein was no longer detectable (30 min), the three preparations of αs (E. coli- and Sf9 cell-derived and the native enzyme) stimulated adenylyl cyclase to similar extents.

Figure 3.

Activation of adenylyl cyclase by N-terminally cleaved αs. αs was purified from rabbit liver (•) or after expression in Sf9 cells (▴) or E. coli (▪), activated with GTP[γS], and digested with 0.01 μg of LysC in 150 μl of 20 mM NaHepes, pH 8.0/1 mM EDTA/2 mM MgCl2/1 mM dithiothreitol/0.05% C12E10 containing 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin at 30°C. Aliquots were withdrawn at the indicated times, Nα-(p-tosyl)lysine chloromethyl ketone (TLCK; 0.8 mg/ml) and aprotinin (0.4 mg/ml) were added, and protein was diluted and mixed with membranes from Sf9 cells expressing type V adenylyl cyclase (A). The proteins in duplicate aliquots were resolved electrophoretically, blotted on nitrocellulose, and visualized using an antibody specific for αs (B). (A) Adenylyl cyclase activities of the reconstituted mixtures. The final concentrations of αs during the assay were 8 nM for the rabbit liver protein and 56 nM and 67 nM for the proteins expressed in Sf9 cells and E. coli, respectively. The data shown are the average of duplicates and are representative of at least two such experiments. In the Inset, activity is expressed as a percentage of the value observed prior to exposure of αs to LysC. (B) The immunoblot was probed with antiserum 584 (29). Arrows show the position of migration of full-length αs protein (f) or the N-terminally cleaved product that accumulates during the incubation with LysC (p). Nondigested αs protein was loaded onto the gel in every other slot (appears as dots).

Hydrophobic Nature of the Modification.

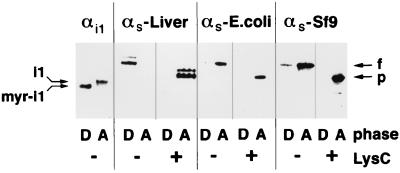

Solutions of the nonionic detergent Triton X-114 are homogeneous at 0°C but separate into aqueous and detergent-rich phases above 20°C. Proteins that are solubilized in the cold solution partition into these two phases according to their hydrophobicity (30). The technique is sensitive, in that myristoylated and nonmyristoylated αi1 are completely resolved (Fig. 4). Native αs from rabbit liver (containing both short and long splice variants) partitioned exclusively into the detergent-rich phase, αs-CH6Sf9 was found predominantly in the aqueous phase, and E. coli-derived αs was found only in the aqueous phase. After treatment with LysC, all three preparations of αs partitioned into the aqueous phase exclusively. Since proteolytic removal of the N terminus of native αs also altered its interactions with adenylyl cyclase, it seems likely that a hydrophobic modification near or at the N terminus of αs is responsible for the different behaviors of the native and recombinant proteins.

Figure 4.

Phase partitioning of Gα proteins in Triton X-114. The proteins utilized were a mixture of myristoylated and nonmyristoylated αi1 and αs purified from liver or synthesized (untagged) in E. coli or Sf9 cells. Note that myristoylated and nonmyristoylated αi1 can be resolved by sodium dodecylsulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Approximately 1 μg of purified protein in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl was activated with GTP[γS], and a portion of each sample was then digested with 0.1 μg of LysC for 15 min at room temperature where indicated. Samples were diluted to 100 μl with 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl and supplemented with 25 μl of 10% Triton X-114. The mixtures were then separated into detergent-rich (D) and aqueous (A) phases by incubation for 1 min at 30°C, followed by centrifugation at room temperature for 0.5 min at 13,000 × g. The separated phases were extracted two more times each with 10% Triton X-114 or buffer, adjusted to contain equal total volumes, and analyzed by sodium dodecylsulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting, using αs- or αi-specific antisera. The positions of full-length αs (f), the proteolyzed αs fragment (p), nonmyristoylated αi1 (i1), and myristoylated αi1 (myr-i1) are marked.

Mutagenesis of Potential Sites of Modification.

Mutation of Gly2 to Ala or of Cys3 to Ser in Sf9 cell-derived αs resulted in production of proteins that could not be distinguished from E. coli-derived αs, whereas mutation of Leu4 or Asn6 to Ala did not change the interaction of αs-CH6Sf9 with adenylyl cyclase (data not shown). The same mutations had no effect on the behavior of the proteins after synthesis in E. coli (data not shown).

Cellular Localization.

Sf9 cells were infected with recombinant baculoviruses encoding αs, αs carrying hexahistidine tags at the N or C terminus or at the site of alternative splicing in exon 3, or αs bearing Gly2 → Ala or Cys3 → Ser mutations. Immunoblotting was used to determine if the αs proteins were soluble or membrane bound. Only the detergent-soluble (1% sodium cholate) membrane-bound fraction was examined. When the proteins were expressed by themselves, 20–40% of each protein was particulate. When the proteins were coexpressed with βγ, the fraction of each protein that was membrane bound increased, such that the range of values was 50–80%. There was no clear capacity of any of the tags or mutations tested to cause predominant distribution of αs to the cytosol (data not shown).

Effect of Palmitoylation.

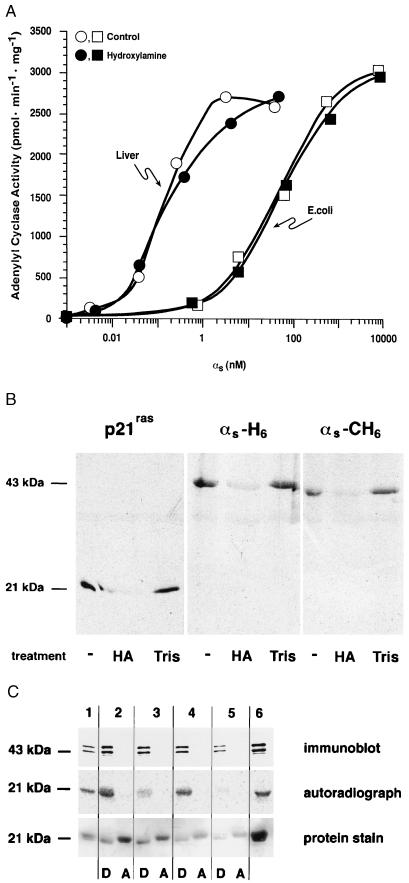

It is difficult to assess the stoichiometry of palmitoylation in vivo, and it is possible that most covalently bound palmitate is lost during purification, either enzymatically or by reaction with dithiothreitol, if present. We tested the capacity of a purified palmitoyl-protein thioesterase (31) to remove radiolabeled palmitate from αs in vitro, with variable results. As an alternative, we treated native and recombinant αs with 1 M hydroxylamine at pH 7.0. Such treatment did not affect the capacity of αs to activate adenylyl cyclase, nor did it alter the apparent affinity of either liver or E. coli-derived αs for adenylyl cyclase (Fig. 5A). This treatment was effective, however, in removing radiolabel from p21ras, αs-H6Sf9, or αs-CH6Sf9 that had been synthesized in vivo in the presence of [3H]palmitate (Fig. 5B) (whereas treatment with 1 M Tris⋅HCl at the same pH was without effect). Of interest, treatment of rabbit liver αs with hydroxylamine did not alter the protein’s behavior in Triton X-114 partitioning experiments; the treated protein was still found exclusively in the detergent-rich phase (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Treatment of native and recombinant αs with hydroxylamine. (A) αs was purified from rabbit liver (○, •) or after expression in E. coli (□, ▪). Proteins were activated with GTP[γS] and then incubated with 1 M hydroxylamine at pH 7.0 (•, ▪) or 1 M Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.0 (○, □), for 30 min at room temperature. Proteins were gel filtered prior to reconstitution at the indicated concentrations with membranes (10 μg) from Sf9 cells expressing type V adenylyl cyclase and assay of αs-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity. (B) His6-tagged (N terminus) p21ras, αs-H6, and αs-CH6 were synthesized in Sf9 cells and labeled in vivo with [3H]palmitic acid. Proteins were enriched by Ni2+-NTA chromatography and treated with 1 M hydroxylamine (HA) or 1 M Tris⋅HCl (Tris) as described for A. Samples were then subjected to sodium dodecylsulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and fluorography. An untreated sample is shown in the first lane for each protein. (C) Purified rabbit liver αs was mixed in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.0/150 mM NaCl with p21ras that had been metabolically labeled with [3H]palmitic acid; this starting material is shown in lanes 1, 2, and 6. Aliquots of this mixture were treated with palmitoyl-protein thioesterase (lane 3), 1 M Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.0 (lane 4), or 1 M hydroxylamine, pH 7.0 (lane 5) and then subjected to Triton X-114 phase partitioning as described in the legend of Fig. 4. Proteins were resolved by electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, and detected by immunoblotting (with an αs-specific antibody), autoradiography, or protein staining (with Ponceau S).

Mass Spectroscopy.

Attempts were made to determine the molecular masses of various α subunits by electrospray mass spectroscopy after removal of detergent by reverse-phase chromatography. Ions with correct masses were observed for E. coli-derived αi1 and E. coli-derived αi1 bearing an internal hexahistidine tag (data not shown). When the latter protein was myristoylated in bacteria by coexpression with N-myristoyltransferase, the increment in mass observed was consistent with myristoylation. When this tagged protein was synthesized in Sf9 cells, a similar larger species was observed. Problematic, however, was our failure to obtain data with native αi1 from Sf9 cells, E. coli-derived myristoylated αi1 with or without palmitate incorporated in vitro (32), or native αi or αo purified from brain. Failures appear ascribable to the presence of lipid modifications, the absence of the internal hexahistidine tag, and/or the possibility of additional covalent modifications that might occur in some cellular settings. We detected the anticipated signals with E. coli-derived αs and with various mutant and tagged mutant constructs of αs. However, no consistent differences were detected between E. coli- and Sf9 cell-derived αs; interpretable data were not obtained with native αs.

DISCUSSION

The findings presented herein are provocative to us but are incomplete because of technical limitations. The evidence indicates that αs, when synthesized in mammalian cells, is covalently modified in a manner that increases its apparent affinity for adenylyl cyclase by roughly 100-fold. Further, the putative modification probably resides near the N terminus, since cleavage of approximately 30 amino acid residues at this site causes the mammalian protein to resemble its bacterially synthesized counterpart. The modification is likely hydrophobic, since it imparts to αs the capacity to distribute into the detergent-rich phase in Triton X-114 partitioning experiments. Finally, palmitoylation of αs does not account for the phenomena described (although αs can be palmitoylated at Cys3), since removal of palmitate with hydroxylamine does not lower the apparent affinity of native αs for adenylyl cyclase or alter its distribution in Triton X-114 partitioning experiments. Conventional purification of oligomeric Gs from rabbit liver or other sources takes several days, and the protein is dissolved in solutions containing dithiothreitol. We doubt that the stoichiometry of palmitoylation of αs would remain high for the duration of such procedures.

Attempts to complete this project by identification of the putative modification have been frustrating. Expression of αs in heterologous systems capable of production of large amounts of the modified protein has not been achieved. Synthesis in yeast is inefficient and, further, the protein resembles that produced in bacteria. The yield of αs from baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells is also disappointing. Furthermore, these cells also appear to modify αs inefficiently (or incorrectly). The apparent affinity of Sf9 cell-derived αs for adenylyl cyclase was notably variable from one preparation to another, but was never as high as that for the rabbit liver protein. Of interest, the variable affinity of Sf9 cell-derived αs for adenylyl cyclase appeared to correlate with the proportion of the protein that distributed into the detergent-rich phase in Triton X-114 partitioning experiments. In most experiments, the bulk of the Sf9 cell-derived αs was found in the aqueous phase, and a relatively low stoichiometry of modification would account for the observed intermediate apparent affinities of this protein for adenylyl cyclase.

E. coli-derived αs also differs from the native protein in having a lower affinity for the G protein βγ subunit complex. Iiri et al. (33) have ascribed this difference to S-acylation of Cys3 of αs with palmitate. We do not refute this observation but note that it was made with αs synthesized in Sf9 cells, and thus with a protein that we presume to be largely lacking the covalent modification hypothesized herein. Either or both the unknown adduct and/or palmitate could influence the affinity of αs for βγ, particularly since both are located near the N terminus—an important site of interaction between α and βγ.

There is little basis for more detailed speculation on the nature and site of the modification of αs, except to note the poor affinities of mutant αs proteins (Gly2 or Cys3) synthesized in Sf9 cells. The cysteine residues that can be palmitoylated in αq are important themselves for interaction of this protein with its effector, phospholipase C-β1 (18). However, mutation at this site of E. coli-derived αs had no effect. The effect of mutation at Gly2 is particularly interesting in view of myristoylation of members of the αi subfamily at this site. If this is a site of modification of αs, it would by necessity occur on the α-amino group of the protein and would likely be metabolically and chemically stable, capable of surviving long-term purification procedures. Unambiguous identification of the modification may require improvements in sample preparation for mass spectrometry and/or development of an expression system for synthesis of larger quantities of protein that more closely resembles native αs. Perhaps almost all Gα proteins are dually modified with lipids at their N termini: most αi family members with myristate and palmitate, αs with X and palmitate, αq and α12 family members with multiple palmitates. The exception is transducin, an α subunit unique in its facile elution from photoreceptor disk membranes by GTP; it is modified only with C14 (and C12) fatty acids at Gly2 (34, 35).

Acknowledgments

We thank Pamela Sternweis for superb technical assistance. This work was supported by a fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to C.K.) and National Institutes of Health Grant GM34497 and the Raymond and Ellen Willie Distinguished Chair in Molecular Neuropharmacology (to A.G.G.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- G proteins

heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory proteins

- C12E10

polyoxyethylene 10-lauryl ether

- NTA

nitrilotriacetate

- GTP[γS]

guanosine 5′-[γ-thio]triphosphate

References

- 1.Casey P J. Science. 1995;268:221–225. doi: 10.1126/science.7716512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wedegaertner P B, Wilson P T, Bourne H R. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:503–506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mumby S M. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:148–154. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wall M A, Coleman D E, Lee E, Iñiguez-Lluhi J A, Posner B A, Gilman A G, Sprang S R. Cell. 1995;83:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambright D G, Sondek J, Bohm A, Skiba N P, Hamm H E, Sigler P B. Nature (London) 1996;379:311–319. doi: 10.1038/379311a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mumby S M, Heuckeroth R O, Gordon J I, Gilman A G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:728–732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones T L Z, Simonds W F, Merendino J J, Jr, Brann M R, Spiegel A M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:568–572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linder M E, Pang I-H, Duronio R J, Gordon J I, Sternweis P C, Gilman A G. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4654–4659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taussig R, Iñiguez-Lluhi J, Gilman A G. Science. 1993;261:218–221. doi: 10.1126/science.8327893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mumby S M, Kleuss C, Gilman A G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2800–2804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wedegaertner P B, Bourne H R. Cell. 1994;77:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90445-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Degtyarev M Y, Spiegel A M, Jones T L Z. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23769–23772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ransnas L A, Insel P A. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17239–17242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wedegaertner P B, Chu D H, Wilson P T, Levis M J, Bourne H R. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25001–25008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wedegaertner P B, Bourne H R, von Zastrow M. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1225–1233. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.8.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parenti M, Vigano M A, Newman C M H, Milligan G, Magee A I. Biochem J. 1993;291:349–353. doi: 10.1042/bj2910349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grassie M A, Mccallum J F, Guzzi F, Magee A I, Milligan G, Parenti M. Biochem J. 1994;302:913–920. doi: 10.1042/bj3020913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hepler J R, Biddlecome G H, Kleuss C, Camp L A, Hofmann S L, Ross E M, Gilman A G. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:496–504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graziano M P, Freissmuth M, Gilman A G. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:409–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee E, Linder M E, Gilman A G. Methods Enzymol. 1994;237:146–164. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)37059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iñiguez-Lluhi J A, Simon M I, Robishaw J D, Gilman A G. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23409–23417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pang I-H, Sternweis P C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7814–7818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kozasa T, Gilman A G. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1734–1741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sternweis P C, Northup J K, Smigel M D, Gilman A G. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:11517–11526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linder M E, Gilman A G. Methods Enzymol. 1991;195:202–215. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)95167-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taussig R, Tang W-J, Hepler J R, Gilman A G. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6093–6100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smigel M D. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:1976–1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higashijima T, Ferguson K M, Smigel M D, Gilman A G. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:757–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mumby S M, Gilman A G. Methods Enzymol. 1991;195:215–233. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)95168-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bordier C. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:1604–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Camp L A, Hofmann S L. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22566–22574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duncan J A, Gilman A G. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23594–23600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iiri T, Backlund P S, Jr, Jones T L Z, Wedegaertner P B, Bourne H R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14592–14597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neubert T A, Johnson R S, Hurley J B, Walsh K A. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18274–18277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kokame K, Fukada Y, Yoshizawa T, Takao T, Shimonishi Y. Nature (London) 1992;359:749–752. doi: 10.1038/359749a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]