Abstract

Exacerbations of asthma during pregnancy represent a significant clinical problem and may be related to poor pregnancy outcomes. A systematic review of the literature was conducted for publications related to exacerbations during pregnancy. Four studies with a control group (no asthma) and two groups of women with asthma (exacerbation, no exacerbation) were included in meta‐analyses using fixed effects models. During pregnancy, exacerbations of asthma which require medical intervention occur in about 20% of women, with approximately 6% of women being admitted to hospital. Exacerbations during pregnancy occur primarily in the late second trimester; the major triggers are viral infection and non‐adherence to inhaled corticosteroid medication. Women who have a severe exacerbation during pregnancy are at a significantly increased risk of having a low birth weight baby compared with women without asthma. No significant associations between exacerbations during pregnancy and preterm delivery or pre‐eclampsia were identified. Inhaled corticosteroid use may reduce the risk of exacerbations during pregnancy. Pregnant women may be less likely to receive oral steroids for the emergency management of asthma. The effective management and prevention of asthma exacerbations during pregnancy is important for the health of both the mother and fetus.

Keywords: pregnancy, exacerbation, loss of asthma control, inhaled corticosteroids, fetus

Asthma affects between 3% and 12%1 of pregnant women worldwide and the prevalence among pregnant women is rising. While it is well recognised that women with asthma are at increased risk of poor pregnancy outcomes,2 the role of asthma exacerbations in contributing to these outcomes is less well established. More research is needed to understand the mechanisms which lead to asthma exacerbations in pregnancy, since improvements in treatment options and management strategies for pregnant women have the potential to lead to significant health benefits for both mother and baby.

This review examines the incidence of asthma exacerbations during pregnancy, explores the evidence for a relationship between asthma exacerbations and adverse perinatal outcomes using meta‐analyses, and reviews the treatment and management of exacerbations of asthma during pregnancy. Studies were identified by the authors through searching the Pubmed database for English language publications with the search term “asthma and pregnancy”. There were 1212 publications from 1950 to 2005. A search of the EMBASE database with the search term “asthma and pregnancy” gave 1250 results covering articles from 1966 to 2005. After screening the titles and/or abstracts, 96 original articles (not literature reviews or single case reports) specifically related to maternal asthma during human pregnancy were identified and retrieved. The reference lists of these articles were hand searched for additional publications about exacerbations during pregnancy. Non‐English language publications were not retrieved. A total of 30 relevant publications are included in this review.

Incidence and causes of asthma exacerbations during pregnancy

Over many decades there have been studies describing the incidence of asthma exacerbations during pregnancy (table 1).

Table 1 Summary of studies investigating the incidence of asthma exacerbations during pregnancy.

| Study | Country | Year | Study design | Asthma (n) | % hospitalised | % ED visits | ICS use | Suspected causes of exacerbation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Williams3 | UK | 1955–65 | Case series | n = 23 | 100% | Nil | Nasorespiratory infection | |

| Gluck and Gluck4 | USA | Case series | n = 47 | 28% | Nil | |||

| Melville et al5 | Jamaica and Trinidad | Case series | Unknown | n = 8 | Unknown | |||

| Stenius‐Aarniala et al6 | Finland | 1972–82 | Prospective cohort | n = 198 | 17% | Some used ICS (up to a maximum dose of 400 μg/day) | ||

| Schatz et al7 | USA | 1978–84 | Prospective cohort | n = 330 | 1.8% | 10.9% | 10% used beclomethasone | |

| Apter et al8 | USA | 1978–88 | Case series | n = 28 | 64% | 43% | 29% used ICS | Discontinuation of medication |

| Viral infection | ||||||||

| Mabie et al9 | USA | 1986–9 | Case series | n = 200 | 42.5% | 13% | Nil | |

| Perlow et al10 | USA | 1985–90 | Historical cohort | n = 81 | 46% | Unknown | ||

| Jana et al11 | India | 1983–92 | Prospective cohort | n = 182 | 8.2% | Some used beclomethasone | ||

| Schatz et al12 | USA | 1978–89 | Prospective cohort | n = 486 | 11.1% received nebulised bronchodilators in clinic or ED | 8% used beclomethasone | ||

| Stenius‐Aarniala et al13 | Finland | 1982–92 | Prospective and retrospective cohort | n = 504 | 6.5% | 3% | ICS used by 34% of those who had an exacerbation and 62% of those who did not have an exacerbation | Lack of ICS use |

| Dombrowski et al14 | USA | 1992–5 | Historical cohort | n = 54 | 43% | 26% used beclomethasone | ||

| 28% used triamcinolone acetonide | ||||||||

| Kurinczuk et al1 | Australia | 1995–7 | Cross sectional survey | n = 79 | 62% had an “asthma attack or wheezing” during pregnancy | Unknown | ||

| Henderson et al15 | USA | 1960–5 | Prospective cohort | n = 1574 | 2.2% | Nil | ||

| Hartert et al16 | USA | 1985–93 | Historical cohort | n = 2461 | 6%(during influenza season) | Unknown | Influenza | |

| Schatz et al17 | USA | 1994–9 | Prospective cohort | n = 1739 overall | 5.1% overall | |||

| n = 873 mild | 2.3% mild | No ICS (mild) | ||||||

| n = 814 moderaten = 52 severe | 6.8% moderate26.9% severe | Some ICS use (moderate and severe) | ||||||

| Namazy et al18 | USA | 1996–2002 | Case series | n = 451 | 7.6% had an “acute attack” | 100% ICS use | ||

| Martel et al19 | Canada | 1990–2000 | Nested case‐control study | n = 3315 | 13% ED or admission | 46% used ICS | ||

| Carroll et al20 | USA | 1995–2001 | Historical cohort | n = 4315 | 6.3% | 11.1% | 16% | |

| Bakhireva et al21 | North America | 1998–2003 | Prospective cohort | n = 654 | 2.5% | 67% used ICS without OCS | ||

| Otsuka et al22 | Japan | 1987–2003 | Historical cohort | n = 592 | 1.38% had “asthma attacks” during labour and delivery | 55.3% | ||

| Schatz and Liebman23 | USA | 2000–1 | Historical cohort | n = 633 | 0.2% | 3.8% | 16% before pregnancy, 10% during pregnancy | Not using ICS before pregnancy |

| Murphy et al24 | Australia | 1997–2003 | Prospective cohort | n = 146 | 8.2% | 2.7% | 64% used ICS | Viral infection |

| Non‐adherence to ICS |

ED, emergency department; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OCS, oral corticosteroid.

Study design

The study designs used have varied from case series to historical cohorts to prospective studies, with a wide variation in the reporting of the incidence of asthma exacerbations during pregnancy. Many of the earlier studies on asthma during pregnancy were case series3,4,8,9 which tend to report a higher incidence of severe exacerbations (28–100% hospitalised) than cohort studies (0.2%–46% hospitalised). These case series are limited by the lack of a control group3 and many focused on women at greater risk of exacerbations or worse perinatal outcomes due to confounding factors such as severe asthma3 or adolescence.8 Longitudinal studies have the advantage of being able to assess exacerbations during the pregnancy in more detail than retrospective studies which rely on hospital records or databases.

Definition of exacerbations

The studies differ in their definition of exacerbations of asthma; however, many report the proportion of women who were hospitalised or treated in the emergency department for asthma. In the eight prospective cohort studies reviewed, the median percentage of women hospitalised for asthma during pregnancy was 5.8%(2.4–8.2% interquartile range). This was similar to that reported by five historical cohort studies (median 6.3%, 6–43%), but much lower than the results from four case series (median 53.3%, 38.9–73%). Most studies focused on severe exacerbations which resulted in medical interventions such as hospitalisation, unscheduled visits to a doctor, or the use of emergency treatment. In the multicentre study by Schatz et al17 as many as 20% of women had exacerbations of asthma requiring medical intervention, even among a group of women with actively managed asthma. There are currently no studies which have examined less severe exacerbations or compared exacerbations of different severities.

It has been suggested that one third of women experience a worsening of asthma during pregnancy, one third have no change, and one third have an improvement in asthma during pregnancy.1,7 Schatz et al7 found that, among women who felt their asthma improved, 8% had an emergency department presentation for an acute asthma attack while, among women who felt their asthma was unchanged, 2% were hospitalised and 17% visited the emergency department.7 These data suggest that even women who report improvements in asthma may require medical intervention for asthma during pregnancy. The concept that only one third of women experience worsening asthma may underestimate the risk of having an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy.

Risk factors for exacerbations

Severe asthma appears to be the biggest risk factor for exacerbations during pregnancy.3 Several studies have shown that the exacerbation rate increases with increasing asthma severity.4,17,24 Few studies have systematically assessed the risk factors of exacerbations during pregnancy, although some have noted that respiratory viral infections3,8,16,24 may have been involved. Pregnant women may be more susceptible to viral infection because of changes in cell mediated immunity during pregnancy which may lead to exacerbations of asthma.4 One study showed that pregnant women with asthma were more likely to have an upper respiratory tract or urinary tract infection during pregnancy (35%) than pregnant women without asthma (5%), and that severe asthma was associated with significantly more infections than mild asthma.25 Viral infection is likely to be an important trigger for asthma exacerbations during pregnancy, although no studies have identified the viruses responsible.

Atopy does not appear to be a risk factor for exacerbations during pregnancy, with one study reporting a higher exacerbation rate among women with non‐atopic asthma.6 Carroll et al20 examined racial differences in the incidence of asthma exacerbations during pregnancy in a low income population in USA and found that the proportion of hospital admissions, emergency department presentations, and use of rescue oral steroids for asthma during pregnancy was significantly higher among blacks than whites, possibly due to inadequate prenatal care.

A major contributor to exacerbations during pregnancy is the lack of appropriate treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).8,13,23,24 Many early studies reporting high rates of exacerbation were conducted before the introduction of ICS medication.3,4,9 In 1996 Stenius‐Aarniala et al13 found that the risk of having an exacerbation was reduced by over 75% among women who were using ICS regularly. This was supported by data from a recent study which found an increase in asthma related emergency department and physician visits during pregnancy among women who did not use ICS before pregnancy.23 Improvements in asthma management which address these issues and reduce the exacerbation rate are needed.

Timing of exacerbations during pregnancy

Exacerbations can occur at any time during gestation, but tend to cluster around the late second trimester.4,8,24 Gluck and Gluck found that the onset of exacerbations was normally distributed around 6 months gestation, with no exacerbations occurring before the fourth month.4 A prospective cohort study of 504 pregnant women with asthma found that the gestational age of onset of exacerbations was normally distributed, with the majority occurring between 17 and 24 weeks gestation (mean 20.8 weeks).13 Similar results were reported by Murphy et al, with exacerbations normally distributed from 9 to 39 weeks gestation around a mean of 25 weeks.24

Acute attacks of asthma during labour are rare. This is consistent with studies showing that asthma is more likely to improve during the third trimester.7 Stenius‐Aarniala et al6 found that 14% of patients with atopic asthma and 22% of patients with non‐atopic asthma experienced asthma symptoms during labour, which were mild and well controlled by inhaled β2 agonists. Similar data have been reported by other groups.7,9,11,22 Jana et al11 noted that none of their patients commenced labour during an acute asthma attack. A recent multicentre study found that 18% of women had asthma symptoms during labour while, of those with severe asthma, 46% experienced symptoms during labour.17

Confounders

A large proportion of pregnant women with asthma smoke and it is unclear whether this increases the risk for exacerbations during pregnancy. One study reported a higher rate of smoking among women who had an exacerbation of asthma (19%v 11% of women who did not have an exacerbation), although the difference was not statistically significant.13 Murphy et al24 found a similar rate of smoking among women who had a severe exacerbation and those without an exacerbation during pregnancy (25%). Some studies have been conducted in populations of low socioeconomic status or in women with additional medical complications including chronic hypertension, diabetes and obesity,9 while other studies have been conducted in women with actively managed asthma who may be less likely to experience exacerbations during pregnancy.17 Few studies have adequately controlled for confounding factors.

Association between asthma exacerbations and adverse perinatal outcomes

There have been conflicting data on the association between asthma exacerbations and adverse pregnancy or fetal outcomes (table 2).

Table 2 Summary of studies investigating the association between asthma exacerbations and perinatal outcomes.

| Study | Country | Year | Study design | Control (n) | Asthma (n) | Exacerbations (n) | Adverse perinatal outcomes associated with exacerbations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gordon et al26 | USA | Historical cohort | n = 30861 (all) | n = 277 | n = 16 (recurrent attacks or status asthmaticus) | Fetal death | |

| Greenberger and Patterson27 | USA | 1981–7 | Case series | n = 80 | n = 25 (emergency treatment or status asthmaticus) | Reduced birth weight (status asthmaticus v no status asthmaticus) | |

| Stenius‐Aarniala et al6 | Finland | 1978–82 | Prospective cohort | n = 198 | n = 198 | n = 90 (acute worsening requiring medical attention)n = 34 (hospitalisation) | Mild pre‐eclampsia (hospitalisation group v women with mild asthma without exacerbations during pregnancy) |

| Schatz et al28 | USA | 1978–84 | Prospective cohort | n = 360 | Number unknown (acute episodes of asthma requiring emergency treatment or hospitalisation) | Lower mean birth weight by 273 g (not statistically significant). | |

| Schatz et al12 | USA | 1978–89 | Prospective cohort | n = 486 | n = 486 | n = 54 (emergency treatment) | None significant (pre‐eclampsia, low birth weight, preterm delivery) |

| Jana et al11 | India | 1983–92 | Prospective cohort | n = 364 | n = 182 | n = 15 (hospitalisation) | Low birth weight (women who were hospitalised compared with asthmatics who were not hospitalised) |

| Stenius‐Aarniala et al13 | Finland | 1982–92 | Prospective and retrospective cohort | n = 237 | n = 504 | n = 47 (asthma not controlled by usual rescue medications and treated as emergency) | None significant (pre‐eclampsia, premature rupture of membranes, gestational diabetes, preterm delivery, perinatal death, emergency caesarean section) |

| Sobande et al29 | Saudi Arabia | 1997–2000 | Prospective cohort | n = 106 | n = 88 | n = 62 (ED presentation) | Reduced birth weightReduced placental weight |

| Pre‐eclampsia (entire asthma group compared to the control group) | |||||||

| Martel et al19 | Canada | 1990–2000 | Case control | n = 4593 pregnancies in 3505 women | n = 1553 (used oral steroids) | Oral steroid use significantly associated with PIH | |

| n = 430 (admission or ED visit for asthma) | Admissions or ED visits during pregnancy not associated with PIH or pre‐eclampsia | ||||||

| Bakhireva et al21 | North America | 1998–2003 | Prospective cohort | n = 303 | n = 654 | n = 16 (hospitalisation), n = 62 unscheduled clinic visits (first trimester), n = 48 unscheduled clinic visits (third trimester) | Among users of oral steroids, hospital admissions, or unscheduled clinic visits were not associated with birth weight |

| Murphy et al24 | Australia | 1997–2003 | Prospective cohort | n = 146 | n = 53 (hospitalisation or ED presentation or unscheduled doctor visit or course of oral steroids) | Reduced birth weight among male neonates (compared to women with no exacerbation) |

ED, emergency department, PIH, pregnancy induced hypertension.

Several studies have found that exacerbations of asthma during pregnancy are associated with low birth weight, pre‐eclampsia, and perinatal mortality. However, other well designed prospective cohort studies have found no significant relationships between asthma exacerbations during pregnancy and poor perinatal outcomes, including preterm delivery, pre‐eclampsia and low birth weight, in women with actively managed asthma.12,13,28

Low birth weight

A study from Saudi Arabia found a lower mean birth weight and placental weight among a group of women with asthma, of whom 70% had an emergency department presentation, compared with a non‐asthmatic control group.29 These women were living at high altitude which may have amplified the effect of asthma exacerbations on fetal hypoxia.

In a series of 80 pregnancies complicated by severe asthma, mean birth weight was 434 g lower in women with at least one episode of status asthmaticus requiring emergency treatment than in women who did not require emergency treatment during pregnancy.27 The authors concluded that, even when oral steroids were used, prevention of status asthmaticus may prevent a reduction in fetal growth, suggesting that the asthma exacerbation itself—rather than the medication used to treat it—may play an important role in this mechanism.

Jana et al11 studied 182 pregnancies in Indian women with asthma and found that 15 had severe asthma during pregnancy which required hospitalisation. Approximately half of these women had a low birth weight neonate and mean birth weight was significantly reduced by 369 g compared with the women who were not hospitalised, where birth weights were similar to the non‐asthmatic control group.11 A recent prospective cohort study from Australia found that women who had a severe exacerbation during pregnancy requiring medical intervention were at increased risk of reduced male birth weight.24

Preterm delivery

The effect of asthma exacerbations on reduced fetal growth is independent of any changes in gestational age at delivery. Several studies which reported reduced birth weight among mothers with exacerbations during pregnancy did not find any increase in the rate of preterm delivery in these women.11,27 However, other studies found an association between oral steroid use and preterm delivery. An historical cohort study of 81 women who all required medication use for asthma found that oral steroid dependent asthmatics were much more likely to have an admission for asthma (71%) than non‐steroid dependent asthmatics (30%), and were at greater risk of preterm labour and delivery (54%) and preterm premature rupture of membranes.10 The risk of preterm delivery may have been associated with the use of oral steroids, as described in more recent studies,30,31 or may have been due to the exacerbation itself.

Pre‐eclampsia and pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH)

Stenius‐Aarniala et al6 found that mild pre‐eclampsia was three times higher in pregnant women who were hospitalised for asthma than in women with asthma who did not experience an exacerbation during pregnancy. This finding may have been confounded by the fact that women who were hospitalised had blood pressure recorded more often than other women and therefore may have been more likely to receive a diagnosis. A larger study from this group found no effect of exacerbations on pregnancy outcomes including pre‐eclampsia, gestational diabetes, premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, perinatal death, and birth weight.13

In a case‐control study Martel et al19 found that exacerbations during pregnancy had no significant effect on the risk of PIH or pre‐eclampsia. However, women who had admissions or emergency department visits for asthma before the pregnancy were at significantly increased risk of both PIH and pre‐eclampsia, suggesting that the underlying severity of asthma may be important.

Perinatal mortality

In 1970 Gordon et al26 studied 277 patients with actively treated asthma, of which 16 had severe asthma characterised by regular acute attacks or status asthmaticus during pregnancy. Six of the 16 women who had exacerbations of asthma had either a spontaneous abortion, fetal death, or neonatal death. This study was conducted before the introduction of ICS medication.

In an historical cohort study, Hartert et al16 examined acute cardiopulmonary hospitalisations during the influenza season among pregnant women in the USA. Of the 297 women who were hospitalised, approximately half had asthma. Although the effect of hospitalisation on perinatal outcomes was not specifically examined in women with asthma, it was noted that there were three stillbirths among the women who were hospitalised, all from mothers with asthma.

Meta‐analyses

Meta‐analyses were conducted to test the hypothesis that asthma exacerbations are associated with the adverse pregnancy outcomes low birth weight, preterm delivery and pre‐eclampsia. The meta‐analyses conformed to standard methodological guidelines.32 Studies were identified by searching Pubmed and EMBASE databases for English language publications with the search term “asthma and pregnancy” as described in the introduction. Studies were hand searched and included if data were available from a control group without asthma and where two groups of women with asthma were described (exacerbation, no exacerbation). Studies also had to describe either the number of low birth weight infants (<2500 g), or the number of preterm deliveries (<37 completed weeks gestation), or the number of women with pre‐eclampsia in each study group. Pre‐eclampsia was defined as an increase in blood pressure noted after the 20th week of gestation (systolic blood pressure >140 and/or diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg) in the presence of proteinuria (>0.3 g/l).

The relative risk of the adverse outcome was examined in each subgroup of women with asthma compared with the control group using Review Manager (Version 4.2.7, Wintertree Software Inc). A fixed effects model was used since there was no significant heterogeneity between studies (χ2 test for heterogeneity, p>0.05). The difference between relative risks for the exacerbation and no exacerbation subgroups was determined using the method of Altman and Bland.33

Overall, four studies met the criteria for inclusion. The quality of the included studies was assessed using an adaptation of the checklist outlined by Duckitt and Harrington.34 Points were scored for participant selection (1 point if the cohort was representative of the general pregnant population, 0 points if cohort was a selected group, or selection not described), comparability of groups (2 points if there were no differences between the groups, particularly in age, parity and smoking status or if differences were adjusted for, 1 point if differences were not recorded and 0 points if groups differed), outcome definition (1 point for acceptable definitions of low birth weight, preterm delivery and pre‐eclampsia, 0 points for unacceptable definitions), outcome diagnosis (2 points for review of notes or prospective assignment, 1 point for use of database coding, 0 points if process not described), sample size (2 points for >100 participants per group, 1 point for <100 participants per group), and cohort design (2 points for prospective, 1 point for retrospective). The study quality assessments are outlined in table 3. Two studies were of high quality (score of 8 out of a maximum of 10),11,12 one was of medium quality (score of 6),13 while one was of low quality (score of 3).26 Study quality did not exert significant bias on the outcomes as the study with the lowest quality had a similar effect size and variation for each pregnancy outcome as the other studies of higher quality.

Table 3 Quality assessment of non‐randomised studies included in meta‐analyses.

All studies had less than 100 participants in the smallest group and all were selected on the basis of acceptable outcome definitions. In the retrospective cohort study by Gordon et al,26 women in the exacerbation group were classified as having severe asthma due to recurrent attacks or status asthmaticus during pregnancy. The selected cohort was not representative of the general obstetric population and the asthma group contained more women of Puerto Rican ethnicity, more older women, and more multiparous women than the overall study population. Jana et al11 used a prospective cohort study design and defined an exacerbation as hospitalisation for severe asthma during pregnancy. Women with asthma were referred to the study by chest physicians and women with additional lung diseases including bronchitis or emphysema were excluded. The study by Schatz et al12 was a prospective cohort study of women who were members of the Kaiser‐Permanente Health Care Program. Cases and controls were matched for age, ethnicity, parity and smoking. An exacerbation was an acute episode with respiratory distress which required the use of nebulised bronchodilators in the emergency department or clinic. The study by Stenius‐Aarniala et al13 was a cohort study which defined exacerbations as acute attacks which were treated as emergencies and were not controlled by the patient's usual rescue medication. The asthmatic population was selected consecutively from both pulmonary medicine and maternity outpatient clinics, with controls (matched for age and parity) selected retrospectively from the hospital labour records.13 The conclusions drawn from the meta‐analyses were not significantly altered by the inclusion or exclusion of particular studies (sensitivity analysis not shown).

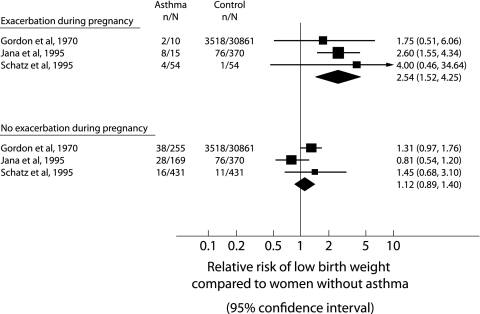

Exacerbations of asthma during pregnancy and the risk of low birth weight

Using data from three studies,11,12,26 there was a significantly increased risk for low birth weight in women who had an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy (relative risk (RR) 2.54, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.52 to 4.25) compared with women without asthma (fig 1). There was no increased risk for low birth weight in asthmatic women who did not have an exacerbation during pregnancy (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.40) compared with women without asthma. The difference between the relative risks of the exacerbation and no exacerbation subgroups was also significant (ratio of relative risk (RRR) 2.27, 95% CI 1.29 to 3.97).33

Figure 1 Meta‐analysis examining the risk of low birth weight infants from asthmatic and non‐asthmatic (control) pregnancies. Studies are grouped based on whether women had an exacerbation during pregnancy or no exacerbation of asthma during pregnancy. The relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals are given.

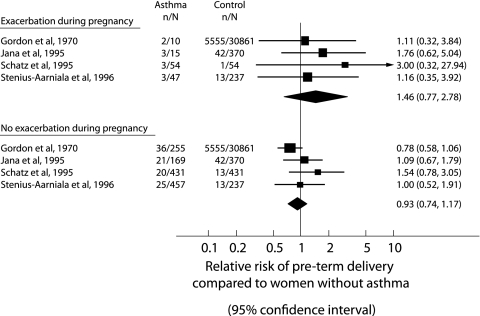

Exacerbations of asthma during pregnancy and the risk of preterm delivery

Using data from four studies,11,12,13,26 there was no significantly increased risk of preterm delivery in women who had an exacerbation of asthma during pregnancy (RR 1.46, 95% CI 0.77 to 2.78) or in women who did not have an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.17) compared with women without asthma (fig 2). There was no difference between the relative risks for the subgroups with or without exacerbations (RRR 1.57, 95% CI 0.80 to 3.1).33

Figure 2 Meta‐analysis examining the risk of preterm delivery from asthmatic and non‐asthmatic (control) pregnancies. Studies are grouped according to whether women had or did not have an exacerbation of asthma during pregnancy. The relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals are given.

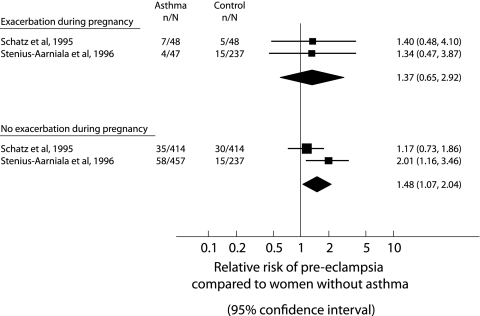

Exacerbations of asthma during pregnancy and the risk of pre‐eclampsia

Using data from two studies (fig 3),12,13 there was no increased risk of pre‐eclampsia among women who had an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy (RR 1.37, 95% CI 0.65 to 2.92); rather, there was a significantly increased risk of pre‐eclampsia in asthmatic women who did not have a severe exacerbation during pregnancy compared with women without asthma (RR 1.48, 95% CI 1.07 to 2.04). However, the difference between the relative risks was not significant (RRR 0.91, 95% CI 0.40 to 2.09).

Figure 3 Meta‐analysis examining the risk of pre‐eclampsia from asthmatic and non‐asthmatic (control) pregnancies. Studies are grouped based on whether women had or did not have an exacerbation during pregnancy. The relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals are given.

In summary, having an exacerbation of asthma during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for low birth weight, but not preterm delivery or pre‐eclampsia. This relationship had a similar effect size to that of maternal smoking during pregnancy, which doubles the risk of low birth weight.35 The mechanisms for the effect of exacerbations on low birth weight are unknown, but may include a direct effect of fetal hypoxia on growth, or changes in fetal growth via reduced uteroplacental blood flow or other alterations in placental function.36 Future studies will need to consider the issue of maternal smoking more carefully, as only one study included in the meta‐analysis considered possible confounding by smoking, with control and asthmatic subjects matched for smoking status.12 A recent report found a doubling of the risk of low birth weight, a significant but smaller increase in the risk of preterm delivery, and a significantly reduced risk of pre‐eclampsia among smokers.35

We speculate that the lack of association between exacerbations and preterm delivery may be due to confounding by treatment with oral steroids which has previously been associated with preterm delivery in several large prospective cohort studies.30,31 While the number of studies investigating pre‐eclampsia as an outcome is small, there appears to be some evidence that the underlying inflammatory disease of asthma may be involved, since women without exacerbation were more at risk of pre‐eclampsia, and a recent large case‐control study identified that asthma severity and control before pregnancy may be associated with an increased risk.19 Other pathogenetic factors may also be playing a role. For example, changes in vascular hyperreactivtiy with asthma may contribute to alterations in uteroplacental blood flow21 with consequences for the development of pre‐eclampsia. Studies of the placenta from asthmatic pregnancies have indicated that there are changes in in vitro vascular responses to both dilator and constrictor agents in women with moderate and severe asthma in the absence of changes in fetal growth.36 The responses observed in the perfused placenta from moderate and severe asthmatics were similar to those previously observed in women with pre‐eclampsia.37

Treatment of exacerbations during pregnancy

A study from the United States found that pregnant women presenting to the emergency department with an asthma exacerbation were significantly less likely to be given oral steroids either in the emergency department or on discharge from hospital than non‐pregnant women.38 The pregnant women were also three times more likely than non‐pregnant women to report an ongoing asthma exacerbation following discharge.38 It is important that treatment should be maximised during any asthma exacerbation which occurs during pregnancy. A severe asthma attack presents more of a risk to the fetus than the use of asthma medications due to the potential reduction in the oxygen supply to the fetus.39 In the event of an asthma emergency, women should receive close monitoring of lung function, oxygen saturation should be maintained above 95%, and fetal monitoring should be considered.39 In cases of severe asthma close cooperation between the respiratory specialist and obstetrician is essential.39

There have been two randomised controlled trials of asthma treatment during pregnancy. Wendel et al40 studied 84 women who had 105 exacerbations during pregnancy. At the time of admission all women who were hospitalised were randomised to receive intravenous aminophylline and methylprednisolone (n = 33) or methylprednisolone alone (n = 32). There was no difference in the length of hospital stay between treatments, but more side effects were reported in women given aminophylline.40 The women were further randomised on discharge to receive inhaled β2 agonist with either oral steroid taper alone (40 mg reduced by 8 mg daily, n = 31) or ICS (beclomethasone) plus oral steroid taper (n = 34). One third of the women required readmission for subsequent exacerbations; however, the inclusion of ICS on discharge reduced the readmission rate by 55%.40

A double blind, double placebo controlled randomised trial from 1995 to 2000 compared the use of inhaled beclomethasone and oral theophylline for the prevention of asthma exacerbations requiring medical intervention (hospitalisation, unscheduled visit to doctor or emergency department, or oral steroid use) in pregnant women with moderate asthma.41 Patients were randomised to the treatments up to 26 weeks gestation, which may have included some patients who were at reduced risk of an exacerbation due to their gestational age. In fact, subjects were excluded if they had severe or unstable asthma which had resulted in a hospital admission for an exacerbation since conception or they had used oral steroids during the previous 4 weeks. Exacerbation rates were similar in the two groups (18% in women receiving beclomethasone v 20% in women receiving theophylline). Significantly more women using theophylline stopped taking the medication due to side effects, and more women on theophylline had an FEV1<80% predicted. Obstetric outcomes such as pre‐eclampsia, preterm delivery, caesarean delivery, and birth weight did not differ between the two treatment groups.41 The results of this trial indicated that inhaled beclomethasone was a suitable alternative to theophylline for the treatment of asthma during pregnancy. There are no randomised trials examining newer ICS medications such as fluticasone or combination therapy with long acting β2 agonists for asthma during pregnancy.

An historical cohort study compared inhaled beclomethasone, oral theophylline, and inhaled triamcinolone acetonide use for asthma during pregnancy and determined the number of subjects admitted to hospital with an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy in each group.14 There were significantly more hospital admissions among women using beclomethasone (79%) than in those using triamcinolone (33%) or theophylline (28%), and a significantly higher proportion of beclomethasone users required oral steroids during pregnancy. However, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution as the numbers of patients in each of the treatment groups was small (15 triamcinolone, 14 beclomethasone, and 25 theophylline). In addition, 50% of the subjects in the beclomethasone group and 27% of the subjects in the triamcinolone group also used theophylline during pregnancy.14

A prospective cohort study found that the risk of exacerbations of asthma during pregnancy was reduced by the use of ICS medication.13 Only 34% of women used ICS prior to an acute asthma attack while 62% of women who did not have an acute attack were using ICS during pregnancy. Following the exacerbation, 94% of women used ICS and 74% were treated with oral corticosteroids.13 Similar data have been reported recently by Schatz and Liebman,23 suggesting the importance of women using appropriate preventer medication for asthma control during pregnancy.

There are few randomised controlled trials of treatments for asthma during pregnancy. However, pregnant women should receive vigorous treatment of an exacerbation during pregnancy to reduce the risk of readmission and to improve outcomes for the fetus. Recent US guidelines for the management of asthma during pregnancy recommend a stepwise approach to treatment with the goal of maintaining control of maternal asthma, as the risks of asthma exacerbations are greater than the risks associated with the use of asthma medications during pregnancy.39

Conclusions

Exacerbations occur in approximately 20% of all pregnant women with asthma and this rate is greatly increased in women with severe asthma. The mechanisms which lead to asthma exacerbations during pregnancy are poorly understood; however, viral infections and discontinuation of anti‐inflammatory medications may play a role. Asthma exacerbations require appropriate treatment in order to protect the fetus as far as possible from adverse outcomes. In particular, the fetus is at risk of being born of low birth weight, which may predispose to diseases in later life. Advancements in the pharmacotherapy and management of asthma during pregnancy have the potential to improve health outcomes for both mother and baby.

Footnotes

Dr Vanessa Murphy was the recipient of a Hunter Medical Research Institute/Port Waratah Coal Services Postdoctoral Fellowship. Conjoint Professor Peter Gibson is an NHMRC Practitioner Fellow. Dr Vicki Clifton was the recipient of the Arthur Wilson Memorial Scholarship from the Royal Australian College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and NHMRC Career Development grant (ID 300786).

The authors have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Kurinczuk J J, Parsons D E, Dawes V.et al The relationship between asthma and smoking during pregnancy. Women Health 19992931–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy V E, Gibson P G, Smith R.et al Asthma during pregnancy: mechanisms and treatment implications. Eur Respir J 200525731–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams D A. Asthma and pregnancy. Acta Allergol 196722311–323. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gluck J C, Gluck P A. The effects of pregnancy on asthma: a prospective study. Ann Allergy 197637164–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melville G N, Kumar M, Wray S R.et al Maternal respiratory function during pregnancy. West Indian Med J 198130207–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stenius‐Aarniala B, Piirila P, Teramo K. Asthma and pregnancy: a prospective study of 198 pregnancies. Thorax 19884312–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schatz M, Harden K, Forsythe A.et al The course of asthma during pregnancy, post partum, and with successive pregnancies: a prospective analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 198881509–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apter A J, Greenberger P A, Patterson R. Outcomes of pregnancy in adolescents with severe asthma. Arch Intern Med 19891492571–2575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mabie W C, Barton J R, Wasserstrum N.et al Clinical observations on asthma and pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Med 1992145–50. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perlow J H, Montgomery D, Morgan M A.et al Severity of asthma and perinatal outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992167963–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jana N, Vasishta K, Saha S C.et al Effect of bronchial asthma on the course of pregnancy, labour and perinatal outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol 199521227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schatz M, Zeiger R S, Hoffman C P.et al Perinatal outcomes in the pregnancies of asthmatic women: a prospective controlled analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 19951511170–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stenius‐Aarniala B S, Hedman J, Teramo K A. Acute asthma during pregnancy. Thorax 199651411–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dombrowski M P, Brown C L, Berry S M. Preliminary experience with triamcinolone acetonide during pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Med 19965310–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henderson C E, Ownby D R, Trumble A.et al Predicting asthma severity from allergic sensitivity to cockroaches in pregnant inner city women. J Reprod Med 200045341–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartert T V, Neuzil K M, Shintani A K.et al Maternal morbidity and perinatal outcomes among pregnant women with respiratory hospitalizations during influenza season. Am J Obstet Gynecol 20031891705–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schatz M, Dombrowski M P, Wise R.et al Asthma morbidity during pregnancy can be predicted by severity classification. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003112283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Namazy J, Schatz M, Long L.et al Use of inhaled steroids by pregnant asthmatic women does not reduce intrauterine growth. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004113427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martel M J, Rey E, Beauchesne M F.et al Use of inhaled corticosteroids during pregnancy and risk of pregnancy induced hypertension: nested case‐control study. BMJ 2005330230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carroll K N, Griffin M R, Gebretsadik T.et al Racial differences in asthma morbidity during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 200510666–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakhireva L N, Jones K L, Schatz M.et al Asthma medication use in pregnancy and fetal growth. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005116503–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otsuka H, Narushima M, Suzuki H. Assessment of inhaled corticosteroid therapy for asthma treatment during pregnancy. Allergol Int 200554381–386. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schatz M, Leibman C. Inhaled corticosteroid use and outcomes in pregnancy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 200595234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy V E, Gibson P, Talbot P I.et al Severe asthma exacerbations during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 20051061046–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minerbi‐Codish I, Fraser D, Avnun L.et al Influence of asthma in pregnancy on labor and the newborn. Respiration 199865130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon M, Niswander K R, Berendes H.et al Fetal morbidity following potentially anoxigenic obstetric conditions. VII. Bronchial asthma. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1970106421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenberger P A, Patterson R. The outcome of pregnancy complicated by severe asthma. Allergy Proc 19889539–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schatz M, Zeiger R S, Hoffman C P. Intrauterine growth is related to gestational pulmonary function in pregnant asthmatic women. Kaiser‐Permanente Asthma and Pregnancy Study Group. Chest 199098389–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sobande A A, Archibong E I, Akinola S E. Pregnancy outcome in asthmatic patients from high altitudes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 200277117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bracken M B, Triche E W, Belanger K.et al Asthma symptoms, severity, and drug therapy: a prospective study of effects on 2205 pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 2003102739–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schatz M, Dombrowski M P, Wise R.et al The relationship of asthma medication use to perinatal outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 20041131040–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stroup D F, Berlin J A, Morton S C.et al Meta‐analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta‐analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 20002832008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altman D G, Bland J M. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ 2003326219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duckitt K, Harrington D. Risk factors for pre‐eclampsia at antenatal booking: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ 2005330565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammoud A O, Bujold E, Sorokin Y.et al Smoking in pregnancy revisited: findings from a large population‐based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 20051921856–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clifton V L, Giles W B, Smith R.et al Alterations of placental vascular function in asthmatic pregnancies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001164546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Read M A, Leitch I M, Giles W B.et al U46619‐mediated vasoconstriction of the fetal placental vasculature in vitro in normal and hypertensive pregnancies. J Hypertens 199917389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cydulka R K, Emerman C L, Schreiber D.et al Acute asthma among pregnant women presenting to the emergency department. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999160887–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.NAEPP expert panel report Managing asthma during pregnancy: recommendations for pharmacologic treatment‐2004 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol 200511534–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wendel P J, Ramin S M, Barnett‐Hamm C.et al Asthma treatment in pregnancy: a randomized controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996175150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dombrowski M P, Schatz M, Wise R.et al Randomized trial of inhaled beclomethasone dipropionate versus theophylline for moderate asthma during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004190737–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]