Abstract

Background

Surgery is considered the treatment of choice for patients with resectable stage I and II (and some patients with stage IIIA) non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), but there have been no previously published systematic reviews.

Methods

A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials was conducted to determine whether surgical resection improves disease specific mortality in patients with stages I–IIIA NSCLC compared with non‐surgical treatment, and to compare the efficacy of different surgical approaches.

Results

Eleven trials were included. No studies had untreated control groups. In a pooled analysis of three trials, 4 year survival was superior in patients undergoing resection with stage I–IIIA NSCLC who had complete mediastinal lymph node dissection compared with lymph node sampling (hazard ratio estimated at 0.78 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.93)). Another trial reported an increased rate of local recurrence in patients with stage I NSCLC treated with limited resection compared with lobectomy. One small study reported a survival advantage among patients with stage IIIA NSCLC treated with chemotherapy followed by surgery compared with chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy. No other trials reported significant improvements in survival after surgery compared with non‐surgical treatment.

Conclusion

It is difficult to draw conclusions about the efficacy of surgery for locoregional NSCLC because of the small number of participants studied and methodological weaknesses of the trials. However, current evidence suggests that complete mediastinal lymph node dissection is associated with improved survival compared with node sampling in patients with stage I–IIIA NSCLC undergoing resection.

Keywords: lung cancer, surgery, meta‐analysis

Complete surgical resection is considered the treatment of choice for individuals with stage I–II non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and has a role in the multi‐modality treatment of resectable stage III A disease.1,2,3 Much of the evidence supporting surgical treatment is observational.4,5 Lederle and Niewoehner6 have argued that these studies cannot be relied on because of the biases inherent in observational data. They also suggest that the negative results of previous lung cancer screening trials have provided indirect evidence against a benefit from surgery. To our knowledge, there have been no previous systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of surgery for NSCLC.1,3,6,7 The purpose of this review is to determine the efficacy of surgery for local and locoregional NSCLC. RCTs comparing surgical resection for early stage lung cancer with no intervention, radiotherapy or chemotherapy were considered. Trials comparing different surgical approaches were also considered. These trials might provide indirect evidence about the efficacy of surgery. The review does not address the efficacy of neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy.

Methods

Searching

A search of electronic databases including MEDLINE (1966 to December 2003), EMBASE (1974 to December 2003), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library Plus, Issue 4, 2003) was undertaken. Full details of the search strategy are outlined elsewhere.8 The journal Lung Cancer was hand searched from 1995 to March 2004, as were abstracts from the annual scientific meetings of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery for 2002 and European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery for 1999 to 2003. Bibliographies were also searched and authors of primary studies and experts in the field were contacted.

Selection

RCTs comparing surgical resection with no treatment or non‐surgical treatment in patients with stage I–IIIA NSCLC were assessed. Studies comparing different types of surgery—for example, lobectomy versus limited resection—were also assessed. Trials were considered eligible if they included individuals with histopathologically or cytologically proven stages I–IIIA NSCLC and reported overall or disease specific survival at 2, 3, 4 or 5 years. Trials comparing surgery alone with surgery plus chemotherapy or radiotherapy were excluded.

Two reviewers (RM and DH) independently assessed titles and abstracts from electronic searches and relevant articles were selected for full text review. Studies were selected for inclusion in the review after the full text articles had been assessed by two reviewers (RM and GW). When assessing the eligibility and quality of studies, the reviewers were aware of the authorship and source of publication of the studies.

Validity assessment

Two reviewers (RM and GW) evaluated the quality of the studies independently with disagreements resolved by consensus. Using the Cochrane approach to allocation concealment, trials were described as having adequate, unclear, or inadequate concealment.9 The adequacy of the method of randomisation was also assessed as described by Jadad et al.10 The reviewers assessed whether there was blinding of outcome assessment and adequate description of withdrawals.10 Finally, an assessment was made as to whether the trial results used intention to treat analysis.11,12 The authors of included studies were asked to verify assessments of study methodology where possible.

Data extraction

Data extracted by one of the reviewers (RM) was entered in the Cochrane Collaboration software (Review Manager Version 4.2 for Windows, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK, 2002). Authors of included studies were asked to confirm the data extracted where possible. A second reviewer (GW) extracted data from graphs, where necessary, for main study outcomes.

Outcome measures

The main outcomes were overall or disease specific survival at 2, 3, 4 or 5 years. Secondary outcomes included progression free survival or recurrence rates (local, distant or both), postoperative mortality or treatment related death, and tests of respiratory function.

Quantitative data synthesis

Outcomes were pooled using the Review Manager and a pooled relative risk was calculated with 95% confidence intervals. Homogeneity of effect sizes among pooled studies was tested using the χ2 statistic for homogeneity with p<0.1 as the level for significance. In the absence of significant statistical heterogeneity, a fixed effects model was used for the pooled analysis.

Because of the broad inclusion criteria it was inappropriate to pool results for all studies. A pooled analysis was conducted on three trials comparing complete mediastinal lymph node dissection (CMLND) with systematic sampling (SS) of nodes.13,14,15 A separate pooled analysis was planned on trials comparing chemotherapy plus surgery with sequential chemotherapy plus radiotherapy in patients with stage IIIA NSCLC.16,17 For the meta‐analysis of survival data, the pooled log hazard ratio was calculated as a weighted average of the individual trial log hazard ratios, with weights inversely proportional to the variance of the log hazard ratio of each trial using the Review Manager software.18,19 None of these studies reported a hazard ratio and variance that would be suitable for meta‐analysis. The methods described by Parmar et al were used to estimate the hazard ratios and variance indirectly from confidence intervals or p values for the log rank test.18 For one study the hazard ratio was extracted from the survival curves using the methods of Parmar et al.14,18 Briefly, in this case the time axis of the survival curve was split into equal non‐overlapping time periods and the log hazard ratio was estimated for each equal time period and then combined in a stratified way across intervals to obtain an overall log hazard ratio. For a further study the authors16 provided original data enabling hazard ratio and variance calculation using the Cox proportional hazards model (Stata Version 6.0 for Windows, Stata Corporation, Texas, 1999).

For the meta‐analysis of studies comparing complete mediastinal lymph node dissection with systematic sampling of mediastinal lymph nodes, follow up for two of the trials was restricted to 4 years so that the time periods of follow up would be comparable between pooled studies.14,15 For the remaining studies a hazard ratio was calculated where possible; otherwise, survival at 2, 3, 4 or 5 years (depending on the data reported for the primary studies) was assessed by entering the number of participants surviving in Review Manager, but a pooled analysis was not conducted.13 Where possible, the statistical analysis was conducted in accordance with intention to treat principles. The level of agreement between reviewers evaluating studies for inclusion was assessed using simple kappa statistics.

Results

Search for trials

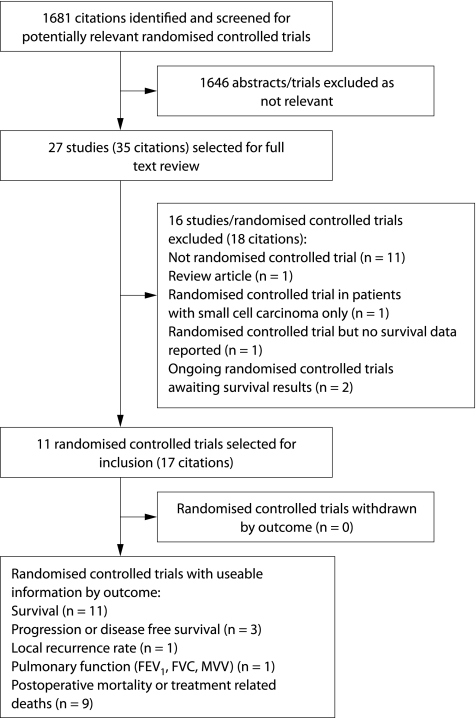

1181 citations were identified by the MEDLINE search, 70 by searching the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and approximately 430 citations were identified by the EMBASE search. After review of abstracts selected from the search of electronic databases, bibliographies and hand searches, 27 papers were selected for full text review. Eleven trials (some with multiple citations) were selected for inclusion in the review.13,14,15,16,17,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 One of these controlled trials was not described as randomised in the report but the primary author confirmed that the study was randomised.16 No trials were identified that included an untreated control group. Ongoing trials were also identified but results are not yet available.29,30,31 Two reviewers (RM and GW) agreed on the studies to be included in all but one case (kappa statistic 0.93). The results of the search are outlined in fig 1. No additional studies were identified by contacting the authors of primary studies or experts.

Figure 1 Results of search for trials and reasons for excluding trials.

Study characteristics

Trials comparing surgery (± other treatment) with non‐surgical treatment arm

Several trials with diverse study designs were included in this category (table 1). Two trials compared chemotherapy followed by surgery with chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy in patients with stage IIIA NSCLC. In one study the inclusion criteria included the demonstration of pathological N2 disease17 but the TNM status of participants was not well described in the other study.16

Table 1 Trials comparing surgery (± other treatment) with non‐surgical treatment arm.

| Study (year) | Subjects | Intervention | Control | Number randomised | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRC, UK (1954–8)25 | Histologically confirmed, clinically locoregional lung cancer* | Thoracotomy and radical resection of tumour with hilar and mediastinal nodes | Radiotherapy (45 Gy to primary and mediastinum) | 58 | Overall 4 year survival |

| NCI, USA (1963–6)27 | Histologically confirmed inoperable locally advanced lung cancer,* potentially operable after radiotherapy | Radiotherapy (40 Gy to primary and mediastinum) followed by surgery | Radiotherapy only (40 Gy to primary and mediastinum) | 425 inoperable patients given radiotherapy, 152 randomised | Overall and disease free 5 year survival |

| National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (before 1997)26‡ | Stage IIIA NSCLC (pN2) fit for surgery, ECOG ⩽2† | Induction chemotherapy followed by surgical resection | Radiotherapy (60 Gy total, 50 Gy to primary tumour and mediastinum, plus 10 Gy to reduced target volume) | 31 | Overall 2 year survival |

| RTOG§ 89–01 trial, USA (1990–4)17‡ | T1–T3 pN2M0 NSCLC | Induction cisplatin based chemotherapy followed by surgical resection | Induction cisplatin based chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy (64 Gy) | 73 given induction chemotherapy, 61 randomised | Overall 4 year survival |

| University of Athens, Greece, (1998–91)16‡ | Stage IIIA NSCLC (exact TNM not stated) Karnofsky performance status 70–90 | 4 cycles cisplatin based chemotherapy followed by surgical resection | 6 cycles of cisplatin based chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy (50 Gy) | 40 | Overall 5 year survival |

| North American Intergroup trial 0139 (RTOG 93–09), (1994–2001)20 | T1–3 pN2M0 NSCLC, surgical resection technically feasible at randomisation | Concurrent cisplatin and etoposide and radiotherapy (45 Gy) followed by surgical resection | Concurrent cisplatin and etoposide and radiotherapy (61 Gy) | 429 | Progression free and overall 3 year survival |

*Includes some cases of small cell lung cancer.

†ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (0 = asymptomatic, 1 = capable of light work, 2 = less then half daylight hours in bed).

‡Trial closed prematurely.

§RTOG, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group.

Studies comparing different surgical approaches for lung cancer

Mediastinal lymphadenectomy (n = 3 studies)

Three studies compared CMLND with SS in patients with resectable NSCLC.13,14,15 Two of these were conducted in patients with resectable stages I–IIIA.13,15 One was limited to patients with peripheral NSCLC less than 2 cm in diameter and without evidence of metastasis.14 For this review the terminology recommended by Keller has been used.30 SS refers to the routine biopsy of lymph nodes at the levels specified by the authors and CMLND refers to the routine removal of all ipsilateral lymph node bearing tissue. Further details are shown in table 2. One reviewer (GW) determined that SS was performed in similar fashion in the three studies, and CMLND was performed according to the techniques of Naruke et al and Martini et al.32,33 In these studies patients with involvement of N2 nodes were offered adjuvant radiotherapy to the mediastinum postoperatively; however, in one study patient uptake in those with N2 disease in both arms was only about 30% according to the author.15

Table 2 Trials comparing different surgical approaches for lung cancer.

| Study and year | Subjects | Intervention | Control | Number randomised | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yamaguchi University, Japan (1993–4)24 | Clinical stage IA NSCLC, no mediastinoscopy | Video‐assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy | Thoracotomy and conventional lobectomy | 100 | Overall 5 year survival |

| Lung Cancer Study Group Trial, North America (1982–8)22 | T1N0M0 peripheral NSCLC fit for lobectomy | Limited resection (wedge resection or segmentectomy, i.e. less than lobectomy) | Conventional lobectomy | 276 | Overall 5 year survival, local recurrence rate, death with cancer rate, pulmonary function |

| University of Munich and Central Hospital, Gauting, Germany (1989–91)13 | Resectable NSCLC (stages I–IIIA) | Thoracotomy, surgical resection, complete mediastinal lymph node dissection | Thoracotomy, surgical resection, systematic sampling of mediastinal lymph nodes | 201 | Overall and progression free survival (median follow up 47 months) |

| Yamaguchi University, Japan (1985–92)14 | Peripheral NSCLC <2 cm diameter, mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes <1 cm on CT (no mediastinoscopy) | Thoracotomy, surgical resection, complete mediastinal lymph node dissection | Thoracotomy, surgical resection, systematic sampling of mediastinal lymph nodes | 115 | Overall 5 year survival |

| Sun Yat‐Sen University of Medical Sciences, Guangzhou, China (1989–95)15 | Pathologically confirmed NSCLC, clinical stages I–IIIA, age <71 years | Thoracotomy, surgical resection, complete mediastinal lymph node dissection | Thoracotomy, surgical resection, systematic sampling of mediastinal lymph nodes | 532 | Overall 5 year survival |

Limited resection (wedge excision or segmentectomy) versus lobectomy

In a multi‐institutional North American study, individuals with proven or suspected T1N0 peripheral NSCLC were randomised to either limited resection (thoracotomy with wedge resection or segmentectomy) or lobectomy.22 All patients were able to tolerate a lobectomy as assessed by cardiopulmonary function. Sublobar resections of up to three segments or wedge resections encompassing the tumour and 2 cm of lung were allowed, at the surgeon's discretion. Pathological stage was confirmed before randomisation at the time of surgery by frozen section. After resection the completeness of resection was assessed by frozen section and clinically and, if the resection was incomplete or the tumour was found to be of a higher stage, the surgeon was required to complete the lobectomy. 276 were randomised at the time of surgery but there were 29 exclusions after randomisation.22

Video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) lobectomy versus conventional lobectomy

One study compared 5 year survival in patients randomised to VATS lobectomy versus conventional lobectomy in patients with clinical stage IA NSCLC.24

Quality of included trials

In the three studies of CMLND versus SS allocation concealment and method of randomisation were found to be adequate (in some cases after contact with the authors).13,14,15 Further quality details of the trials are shown in table 3. None of the included studies contained a clear statement that they had conducted an intention to treat analysis. However, this information was inferred from information provided about analysis and results for some of the trials. For two trials there were no crossovers after randomisation but there were a number of exclusions after randomisation, not strictly adhering to intention to treat analysis.11,13,15

Table 3 Methodological quality of included trials.

| Study | Allocation concealment | Method of randomisation | Blinded assessment of outcome | Description of withdrawals | Intention to treat analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRC, UK25 | Adequate | Not reported | None described | No description | Yes* |

| NCI, USA27 | Adequate | Not reported | None described | Yes | Yes |

| National Cancer Institute of Canada trial, North America26 | Adequate† | Adequate† | No | No losses† | Yes† |

| RTOG‡ 89–0117 | Not reported | Not reported | None described | Incomplete description | No |

| University of Athens, Greece16 | Not reported | Not reported | None described | No description | No |

| Intergroup 0139 trial (RTOG‡ 93–09), North America20 | Not reported | Not reported | None described | Incomplete description | No |

| Yamaguchi University (VATS v open)24 | Inadequate | Inadequate | None described | No losses† | No |

| Lung Cancer Study Group trial, North America22 | Adequate | Not reported | None described | Yes (N.B. 18% loss in each group) | Unclear |

| University of Munich13 | Adequate† | Adequate | Yes§ | Yes | No |

| Yamaguchi University14 | Adequate† | Adequate | None described | Yes | Yes |

| Sun Yat‐Sen University of Medical Sciences, Guangzhou15 | Adequate† | Adequate† | None described | Yes | No |

*Unclear if losses to follow up.

†Confirmed by contacting authors.

‡RTOG, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group.

§Investigators undertaking follow up blinded from treatment group.

Data synthesis

Trials comparing surgery (± other treatment) with non‐surgical treatment arm

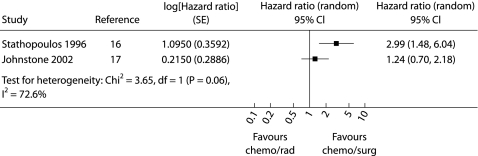

The results of four trials included in this category are shown in table 4.20,25,26,27 These trials were diverse in terms of the interventions and populations and therefore not suitable for pooled analysis. In none of the studies was the surgical treatment arm found to be significantly superior to the non‐surgical group in terms of overall survival. The authors intended to conduct a pooled analysis of the two studies comparing chemotherapy followed by surgery with chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy but there was significant statistical heterogeneity between these studies (χ2 statistic for homogeneity 3.65, p = 0.06) so a pooled analysis was not performed. The results of these individual studies are shown in fig 2. In one study there were two treatment related deaths in the chemotherapy/surgery group and one in the chemotherapy/radiotherapy group (relative risk (RR) 2.21 (95% CI 0.21 to 23.08), p = 0.51).17 Treatment related deaths were not described in the other trial.16

Table 4 Overall survival and progression free survival for trials comparing surgery (± other treatment) with non‐surgical treatment.

| Study | Arm 1 | Arm 2 | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRC, UK25 | Surgery | Radiotherapy | |

| 4 year OS 23% | 4 year OS 7% | 3.27 (0.74 to 14.42), p = 0.12 | |

| Squamous cell subgroup analysis 30% | Squamous cell subgroup analysis 6% | 5.10 (0.68 to 38.29), p = 0.11 | |

| NCI, USA27 | Initially inoperable, radiotherapy | Initially inoperable, radiotherapy | |

| Surgery | No surgery | ||

| 5 year OS 8% | 5 year OS 6% | 1.42 (0.42 to 4.81), p = 0.57 | |

| 5 year PFS 6% | 5 year PFS 4% | 1.58 (0.39 to 6.38), p = 0.52 | |

| National Cancer Institute of Canada, North America26 | Chemotherapy then surgery | Radiotherapy | |

| 2 year OS 44% | 2 year OS 40% | 1.09 (0.48 to 2.51) | |

| Intergroup 0139 trial (RTOG 93–09), North America20 | Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy then surgery | Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy | 1.53 |

| Treatment deaths 14 | Treatment deaths 3 | 4.43 (1.29 to 15.19), p = 0.02 | |

| 3 year PFS 29% | 3 year PFS 19% | (1.06 to 2.21), p = 0.02 | |

| 3 year OS 38% | 3 year OS 33% | 1.16 (0.89 to 1.52), p = 0.27 |

OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival; RTOG, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2 Hazard ratio (4 year survival) for studies comparing chemotherapy plus radiotherapy with chemotherapy plus surgery in patients with respectable stage IIIA NSCLC. The squares represent the hazard ratios for the individual trials and the line represents the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. © Cochrane Library (reproduced with permission).

Studies comparing different surgical approaches for lung cancer

Mediastinal lymphadenectomy

A pooled analysis (fixed effects model) was conducted comparing hazards (or mortality rate) over the first 4 years after randomisation for the three studies included in this category. There was a significant reduction in the risk of death in the group undergoing CMLND (fig 3) with a pooled hazard ratio estimated at 0.78 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.93; p = 0.005). There was no significant statistical heterogeneity between studies being pooled (χ2 statistic = 0.13; p = 0.94). A subgroup analysis by stage was not conducted due to the possibility of stage migration in the CMLND group (Will Rogers phenomenon).34 In one trial there was a non‐significant trend to improved disease free survival in the CMLND group with a median follow up of 47.5 months; the hazard ratio was reported to be 0.82 (95% CI 0.54 to 1.27).13 The remaining trials did not report time to event data for disease recurrence so meta‐analysis was not possible.

Figure 3 Hazard ratio (4 year survival) for studies comparing complete mediastinal lymph node dissection with mediastinal node sampling. For the individual trials the squares represent the hazard ratios and the line represents the 95% confidence intervals. The diamond represents the results of the pooled analysis using the fixed effect model. © Cochrane Library (reproduced with permission).

None of the trials individually found a significant difference between the groups in terms of 30 day operative mortality. In the pooled analysis the relative risk was 0.86 (95% CI 0.19 to 3.77, p = 0.84) without significant statistical heterogeneity between studies being pooled (p = 0.39).

Limited resection versus lobectomy

In the study comparing limited resection with lobectomy in patients with peripheral stage I NSCLC, limited resection was associated with an increased risk of locoregional recurrence (RR 2.84 (95% CI 1.32 to 6.1), p = 0.007).22,23 There was also a trend to improved overall survival with 5 year survival of 74% in the lobectomy group and 55% in the limited resection group.24 The hazard ratio was 0.67 (95% CI 0.44 to 1.02, p = 0.062). There was a trend to an increased mortality rate from cancer in the limited resection group compared with the lobectomy group (RR 1.46 (95% CI 0.87 to 2.45), p = 0.15). It is not clear if the results presented above were based on an intention to treat analysis; however, the investigators involved in the Lung Cancer Study Group trial also conducted an analysis that included all patients randomised but actual results were not provided in the published report.22,23 There was less reduction (from the preoperative level) in forced expiratory volume in 1 second at 12–18 months (mean % difference) in the limited resection group than in the lobectomy group. The mean difference between groups was 5.91 (95% CI 0.29 to 11.53, p = 0.04). However, this difference is of doubtful clinical significance and, furthermore, less than 67% of participants had lung function results available at 12–18 months. There were two postoperative deaths in the lobectomy group and one in the limited resection group, but these figures were for all 276 individuals randomised and it was not clear from the report22 what the denominator was for each group.

VATS lobectomy versus conventional lobectomy

In the one study in this category the 5 year survival rate was 85% in the open group and 90% in the VATS group (RR 1.09 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.23, p = 0.46).24

Discussion

Eleven trials with a total of 1910 patients were included in this review. No studies were identified comparing surgery alone with a no treatment arm. Only one study included patients with local and locoregional NSCLC and compared surgery alone with radiotherapy alone.25 However, although there was a trend to improved survival in the subgroup with squamous cell carcinoma in this study, this did not reach statistical significance in our analysis.26 The review also shows that the role of surgery in combined modality treatment for stage IIIA NSCLC is unclear. One study comparing chemotherapy followed by surgery with sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy was inconclusive because of small numbers.17 A similar study found in favour of chemotherapy plus surgery compared with sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy in stage IIIA disease. However, the results were not based on intention to treat analysis and it is possible that an imbalance between unknown prognostic factors could have occurred in this small study.16

Although the Lung Cancer Study Group trial showed that there was a significant increase in local recurrence in the limited resection group, the trend to a reduction in the rate of death with cancer and death from all causes in the lobectomy group did not reach statistical significance at the conventional 5% level.22 The study was designed to show equivalence between the two groups and therefore a more conservative p value of p>0.1 was used as acceptable evidence of equivalence. However, the 95% confidence intervals for the hazard ratio for 5 year overall survival are wide (0.44 to 1.02) and encompass equivalence. Likewise, they do not exclude a clinically important difference between the two groups.

The results of studies comparing CMLND with SS are of particular interest with respect to the efficacy of surgery in general and future surgical practice. In the pooled analysis of the three studies there was a significant reduction in death from all causes in the group undergoing CMLND. These results suggest that the risk of dying on any given day (given survival to that point) is 78% (95% CI 65 to 93) for the CMLND group compared with the SS group.

The quality of the primary studies should be taken into account when interpreting the results of this review. Several studies in this review have some methodological weaknesses that represent serious threats to the validity of the findings.22,24 In particular, the Lung Cancer Study Group trial reported high rates of losses to follow up in both groups and did not clearly state whether patients were analysed according to treatment received or treatment assigned.22 In addition, blinded assessment of outcome was not undertaken in this study and the high local recurrence rate in the limited resection group could, to some extent, reflect a detection bias. Furthermore, several trials excluded participants after randomisation in a manner that would not strictly fulfil the criteria for an intention to treat analysis.12,13,15 It is difficult to draw any conclusions about the role of VATS versus conventional lobectomy because the only study included in this review was small and the analysis was not by intention to treat.24

Few trials included in this review have described the experience of the surgeons involved in performing surgery. The efficacy of the intervention may be influenced by the experience of the surgeons.35 This information is required when making judgements about the generalisability of any findings.

In summary, the current evidence from RCTs neither supports nor discounts the survival benefit of surgery for NSCLC. However, as more extensive (complete) surgery appears superior to less, by inference some surgery might be better than no surgery. In particular, compared with limited resection, lobectomy was shown to reduce the rate of local recurrence in individuals with stage I NSCLC in one study. CMLND appears to improve survival compared with SS in individuals with resected NSCLC. The results of the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z30 trial will be important to further clarify this issue.30 Similarly, the results of ongoing trials should help to clarify the role of surgery following induction chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy for patients with stage IIIA (N2) NSCLC.20,29 Further details of ongoing trials identified by this review are outlined elsewhere.8 If ongoing trials show that surgery does not significantly improve survival after induction chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy in patients with stage IIIA (N2) NSCLC, then it may be reasonable to conduct further RCTs comparing surgery with radiotherapy or chemoradiation in selected groups of patients with earlier stage NSCLC—for example, in older patients in whom the perioperative mortality of surgery is on average 6% for patients aged 70–79 years and 8% for those aged 80 years and older,36 or in patients with reduced respiratory reserve.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Iberoamerican Cochrane Center for assistance with database searches and Dr Sera Tort, Dr Marta Roque and Dr Elinor Thompson (coordinators of the Cochrane Lung Cancer Group) for assistance with protocol development and editing of the review. They also acknowledge the help provided by authors of primary studies who have responded to correspondence and provided additional information. Some of the narrative in the text, tables 1, 2 and 3, and figures 2 and 3 of the present article also appear in the Cochrane Review (© Cochrane Library, reproduced with permission).

Abbreviations

CMLND - complete mediastinal lymph node dissection

NSCLC - non‐small cell lung cancer

RCT - randomised controlled trial

SS - systematic sampling

VATS - video assisted thorascopic surgery

Footnotes

Dr Manser is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council postgraduate scholarship (scholarship number 201713).

Competing interests: none.

References

- 1.Reif M, Socinski M A, Rivera M P. Evidence‐based medicine in the treatment of non‐small cell lung cancer. Clin Chest Med 200021107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott W, Howington J, Movsas B. Treatment of stage II non‐small cell lung cancer. Chest 2003123(Suppl 1)188–201S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smythe W. Treatment of stage I non‐small cell lung carcinoma. Chest 2003123(Suppl 1)181–7S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flehinger B J, Kimmel M, Melamed M R. The effect of surgical treatment on survival from early lung cancer. Implications for screening. Chest 19921011013–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobue T, Suzuki T, Matsuda M.et al Survival for clinical stage I lung cancer not surgically treated: comparison between screen‐detected and symptom‐detected cases. Cancer 199269685–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lederle F, Niewoehner D E. Lung cancer surgery: a critical review of the evidence. Arch Intern Med 19941542397–2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones D, Detterbeck F C. Surgery for stage I non‐small cell lung cancer. In: Detterbeck F, Rivera MP, Socinski MA, Rosenman JG, eds. Diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer‐ an evidence based guide. Philadelphia: W B Saunders, 2001177–190.

- 8.Manser R, Wright G, Hart D.et al Surgery for early stage non‐small cell lung cancer (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Clarke M, Oxman A D. eds. Cochrane reviewers' handbook 4.1. Oxford, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000

- 10.Jadad A, Moore R A, Carroll D.et al Assessing the quality of reports of randomised clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996171–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montori V, Guyatt G H. Intention‐to‐treat principle. Can Med Assoc J 20011651339–1341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fergusson D, Aaron S D, Guyatt G.et al Post‐randomisation exclusions: the intention to treat principle and excluding patients from analysis. BMJ 2002325652–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Izbicki J, Passlick B, Pantel K.et al Effectiveness of radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy in patients with resectable non‐small cell lung cancer: results of a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg 1998227138–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugi K, Nawata K, Fujita N.et al Systematic Lymph node dissection for clinically diagnosed peripheral non‐small cell lung cancer less than 2 cm in diameter. World J Surg 199822290–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Y‐l, Huang Z‐F, Wang S‐Y.et al A randomised trial of systematic nodal dissection in resectable non‐small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2002361–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stathopoulos G, Papakostas P, Malamos N A.et al Chemo‐radiotherapy versus chemo‐surgery in stage IIIA non‐small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep 19963673–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnstone D, Byhardt R W, Ettinger D.et al Phase III study comparing chemotherapy and radiotherapy with preoperative chemotherapy and surgical resection in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer with spread to mediastinal lymph nodes (N2). Final report of RTOG 89‐01. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 200254365–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parmar M, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta‐analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med 1998172815–2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitehead A, Whitehead J. A general parametric approach to the meta‐analysis of randomised clinical trials. Stat Med 1991101665–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albain K, Scott C B, Rusch V R.et al Phase III study of concurrent chemotherapy and full course radiotherapy (CT/RT) versus CT/RT induction followed by resection for stage IIIA (pN2) NSCLC. Lung Cancer 200341(Suppl 2)S4 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izbicki J, Passlick B, Karg O.et al Impact of radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy on tumour staging in lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 199559209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ginsberg R, Rubinstein L V, for the Lung Cancer Study Group Randomised trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1N0 non‐small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 199560615–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubinstein L, Ginsberg R J. Lobectomy versus limited resection in T1N0 lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 1996621249–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugi K, Kaneda Y, Esato K. Video‐assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy achieves a satisfactory long term prognosis in patients with clinical stage 1A lung cancer. World J Surg 20002427–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrison R, Deeley T J, Cleland W P. The treatment of carcinoma of the bronchus: a clinical trial to compare surgery and supervoltage radiotherapy. Lancet 19631683–684. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shepherd F, Johnston M R, Payne D.et al Randomised study of chemotherapy and surgery versus radiotherapy for stage IIIA non‐small‐cell lung cancer: a National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study. Br J Cancer 199878683–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warram J, on behalf of collaborating investigators Preoperative irradiation of cancer of the lung: final report of a therapeutic trial (a collaborative study). Cancer 197536914–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warram J, on behalf of collaborating investigators Preoperative irradiation of cancer of the lung: preliminary report of a therapeutic trial (a collaborative study). Cancer 196923419–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Splinter T, van Schil P E, Kramer G W P M.et al Randomised trial of surgery versus radiotherapy in patients with stage IIIA (N2) non‐small cell lung cancer after response to induction chemotherapy (EORTC 08941). Clin Lung Cancer 2000269–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keller S. Complete mediastinal lymph node dissection – does it make a difference? Lung Cancer 2002367–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen M, for the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (Thoracic Organ Site Committee) Randomised trial of mediastinal lymph node sampling versus complete lymphadenectomy during pulmonary resection in patients with N0 or N1 (less than hilar) non‐small cell lung cancer. Available at http://www.acosog.org/studies/synopses/Z0030_Synopsis.pdf (accessed October 2004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Naruke T, Suemasu K, Ishikawa S. Surgical treatment for lung cancer with metastasis to mediastinal lymph nodes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 197671279–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martini N, Flehinger B J. The role of surgery in N2 lung cancer. Surg Clin North Am 1987671037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feinstein A, Sosin D M, Wells C K. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med 19853121604–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bach P, Cramer L D, Schrag D.et al The influence of hospital volume on survival after resection for lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2001345181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiser A, Detterbeck F C. General aspects of surgical treatment. In: Detterbeck F, Rivera MP, Socinski MA, Rosenman JG, eds. Diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer: an evidence based guide. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001133–147.