Abstract

Statins reduce cholesterol levels by inhibiting 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG‐CoA) reductase and have an established role in the treatment of atherosclerotic disease. Recent research has identified anti‐inflammatory properties of statins. Statins appear to reduce the stability of lipid raft formation with subsequent effects on immune activation and regulation, and also prevent the prenylation of signalling molecules with subsequent downregulation of gene expression. Both these effects result in reduced cytokine, chemokine, and adhesion molecule expression, with effects on cell apoptosis or proliferation. This review considers the evidence for the anti‐inflammatory properties of statins in the lung, and how these effects are being applied to research into the role of statins as a novel treatment of respiratory diseases.

Keywords: asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, statins

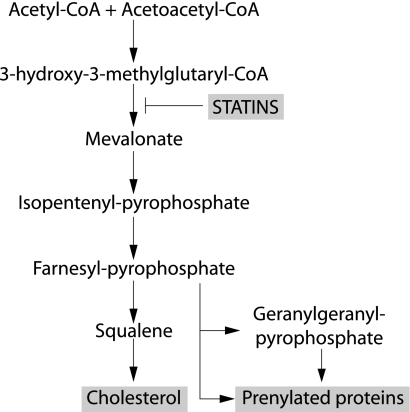

Statins are a class of cholesterol lowering drugs that decrease mortality from cardiovascular disease1,2,3 and stroke.4,5 The beneficial effects of statins have been attributed to reduced cholesterol biosynthesis through competitive inhibition of the enzyme 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG‐CoA) reductase (fig 1). These studies also showed that treatment with statins provided greater protection than predicted from cholesterol reduction.6 Evidence has accumulated that statins lower C‐reactive protein (CRP),7,8,9,10 a key indicator of inflammation, which itself is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular mortality and morbidity.11,12 This reduction in CRP is probably a consequence of the ability of statins to reduce the production of interleukin (IL)‐6,13,14 the cytokine which activates the acute phase CRP response.15 Based on these observations, it has been proposed that the clinical effectiveness of statins might be due to a combination of functions including cholesterol reduction, anti‐inflammatory, antithrombotic and immunomodulatory effects.

Figure 1 Cholesterol biosynthesis pathway showing potential effects of inhibition of 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG‐CoA) reductase by statins, causing a decrease in prenylation of signalling molecules as well as derivatives from mevalonate and cholesterol.

The purpose of this review is to outline the evidence for the anti‐inflammatory properties of statins using observations from ex vivo and in vitro cell function, from experimental disease models, and clinical trials, and to suggest how these may be applicable to therapeutic advances for inflammatory lung disease.

Mechanism of action

Statins have several possible mechanisms of action that may be interrelated which result in the reduction of inflammation. These include (1) modulating the cholesterol content and thus reducing the stability of lipid raft formation and subsequent effects on the activation and regulation of immune cells, and (2) preventing the prenylation of signalling molecules and subsequent downregulation of gene expression, both resulting in reduced expression of cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules with effects on cell apoptosis or proliferation.

Other less well known anti‐inflammatory properties of statins have been described, including antioxidant effects of some statins related to their ability to scavenge oxygen derived free radicals.16

Lipid rafts formation

Lipid rafts are small cell membrane structures or microdomains, rich in cholesterol and glycosphingolipid, which house intracellular enzymes, mainly kinases. These lipid rafts can be translocated by the actin cytoskeleton which controls their specific redistribution, clustering, and stabilisation within the cell membrane. When these rafts are assembled they form critical sites for processes such as cell movement, intracellular transport, or signal transduction. Lipid rafts act as platforms, bringing together molecules essential for the activation of immune cells, but also separating such molecules when the conditions for activation are not appropriate. Several strands of evidence suggest that the inhibition of cholesterol synthesis by statins disrupts these lipid rafts and thereby influences the function of lymphocytes.17 A central component of the interaction between lymphocytes and antigen presenting cells, which results in T cell activation, is interferon γ (IFN‐γ) induced upregulation and assembly of the major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC‐II). Statins reduce IFN‐γ production by Th1 cells18 and thus act as repressors of MHC‐II mediated T cell activation.19,20

Prenylation and regulation of cytokine synthesis

Altered cytokine synthesis observed with statin therapy may be a consequence of altered lipid raft formation. However, there is an alternative or additional pathway of cytokine synthesis that may be affected by statins. The mevalonate synthetic pathway mediated by HMG‐CoA reductase is crucial for the biosynthesis of isoprenoids (fig 1), which are essential for normal cellular proliferation and activity. Farnesyl pyrophosphate is a later intermediate on this pathway and serves as a precursor for the synthesis of various isoprenoids—for example, geranylgeranyl or farnesyl groups—which prenylate proteins through covalent links. These can anchor these proteins to lipid rafts. Many prenylated proteins play important roles in the regulation of cell growth, cell secretion, and signal transduction. Thus, by inhibiting prenylation, statins affect many cell processes involved in inflammation.

Anti‐inflammatory effects of statins on non‐respiratory cells and diseases

These two complementary mechanisms of prenylation and lipid raft stability allow statins to affect the function of many different cells and to attenuate inflammation in experimental models of disease.

Cell adhesion molecules

Statins interfere with cell binding by reducing leucocyte–endothelial cell adhesion.21,22 This occurs because statins attenuate the upregulation of P‐selectin normally seen on activated endothelial cells,23 and they also interfere with monocyte24 and lymphocyte attachment to endothelium by suppressing intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM‐1) and lymphocyte function associated antigen 1 (LFA‐1) interactions.25 Statins have been shown to decrease the expression of the receptor for chemoattractant chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) expression on endothelial cells in rats26 and on monocytes from pigs,27 and thereby reduce monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelium.

Cytokine and mediator release

Statins alter protein expression, seen in altered cytokine release. In vitro experiments looking at spontaneous and lipopolysaccharide induced secretion of IL‐6 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α in human cell lines showed reduced output due to statins in both cases.13,28 Fluvastatin and simvastatin (but not pravastatin) reduce production of IL‐6 and IL‐1β in human umbilical vein endothelial cells.29 Atorvastatin has also been shown to inhibit production of TNF‐α.30 Lovastatin induces Th2 production of IL‐4, IL‐5, and IL‐10 in vitro.18 Increased prostacyclin31 and decreased endothelin32 production are seen in human endothelial cells after statin treatment.

Cellular apoptosis or proliferation

Statins increase apoptosis, as shown in human vascular endothelial cells33 and in plasma cell lines from patients with multiple myeloma.34 Proliferation of T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes is inhibited by statins,35,36 and statins can alter the ratio of Th1 to Th2 lymphocytes; cerivastatin, simvastatin, lovastatin, and atorvastatin can promote Th2 polarisation through suppression of Th1 lymphocyte development and augmentation of Th2 lymphocyte development from naive CD4+ T cells when primed in vitro.37 Statins also reduce the proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts in rat and rabbit models.38

Antioxidant effects

Metabolites of atorvastatin have been shown to possess potent antioxidative properties,39,40 and to protect very low density lipoprotein (VLDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), and high density lipoprotein (HDL) from oxidation.41 Simvastatin acts as an antioxidant in rat liver microsomes,42 vascular smooth muscle,43 and human lipoprotein particles,44 which may contribute to its anti‐atherogenic effect.

Experimental models of disease

Statins have diverse effects on many chronic animal models of autoimmune disease. In models of systemic lupus erythematosus the administration of atorvastatin resulted in a significant reduction in serum IgG anti‐dsDNA antibodies and decreased proteinuria, reduced glomerular immunoglobulin deposition, and glomerular injury. Disease improvement was paralleled by decreased expression of MHC‐II on monocytes and B lymphocytes. T cell proliferation was impaired by atorvastatin in vitro and in vivo and a significant decrease in glomerular MHC‐II expression was also observed.45 Cerivastatin and simvastatin have also been shown to inhibit the human neutrophil response to ANCA in vitro.46

In experiments with collagen induced arthritis in mice, simvastatin was given intraperitoneally either before (prophylactically) or after (therapeutically) induction of arthritis and a marked reduction in serum IL‐6 and IFN‐γ was seen, with a significant histological improvement.47

In a mouse model of autoimmune retinal disease, treatment with 20 mg/kg/day intraperitoneal lovastatin over 7 days suppressed clinical ocular pathology, retinal vascular leakage, and leucocytic infiltration into the retina.48 The effect was reversed by co‐administration of mevalonolactone, the downstream product of HMG‐CoA reductase.

Clinical studies

A double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial examined the efficacy of atorvastatin 40 mg daily for 6 months in rheumatoid arthritis. At the end of that period, patients who had received statin were found to have decreased plasma levels of lipids, fibrinogen and viscosity. The disease activity score improved significantly on atorvastatin treatment compared with placebo. CRP levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate reduced by 50% and 28%, respectively, relative to placebo.49

Different statins may have different anti‐inflammatory properties

It has recently become apparent that the different families of statins may have different biochemical functions. Kiener and colleagues50 showed that lipophilic statins such as atorvastatin and simvastatin have a much greater effect on inflammatory responses in human and mouse models than the hydrophilic pravastatin. Similarly, when looking at sensitisation of human smooth muscle cells to apoptotic agents, lovastatin and simvastatin had a powerful sensitising effect, atorvastatin had less of an effect, and pravastatin had no activity.51 There is also a dose‐response effect—for example, cerivastatin is much more potent than fluvastatin in blocking NF‐κB activation in human blood monocytes.52 Some statins have differing effects on protein expression—for example, in monocytes stimulated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), pravastatin and fluvastatin may induce production of TNF‐α, IFN‐γ, and IL‐1853,54 whereas atorvastatin and simvastatin inhibit production of TNFα.13,14,30,55

It is therefore important to recognise that all statins may not have the same therapeutic potential. For example, a clinical study in 27 healthy volunteers found significant differences between the ex vivo immunological responses after atorvastatin and simvastatin treatment. Atorvastatin led to a significant downregulation in the expression of human leucocyte antigen (HLA)‐DR and of the CD38 activation marker on peripheral T cells, whereas simvastatin upregulated both these molecules. In contrast, superantigen mediated T cell activation was inhibited by simvastatin and enhanced by atorvastatin.56

Potential therapeutic role for statins in respiratory disease

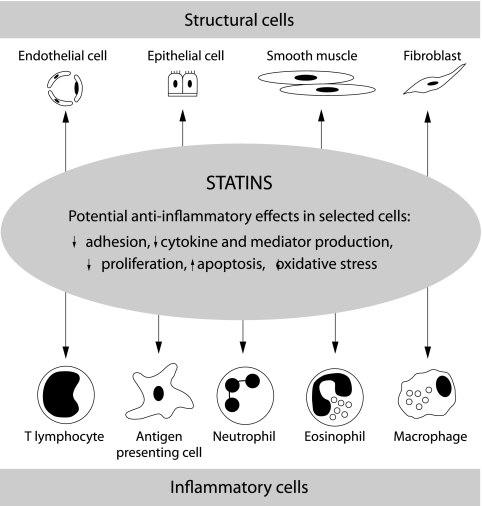

The therapeutic effect of statins on cardiovascular and autoimmune disease seems to be broadly anti‐inflammatory, which is also likely to apply to lung diseases in which there is an inflammatory component (fig 2).

Figure 2 Potential anti‐inflammatory effects of statins on different structural and inflammatory cells within the lungs.

Cellular inflammatory processes in the lung

There are several inflammatory processes in the lung that may be susceptible to the effects of statins.

Statins could affect the chemokine and adhesion molecule directed migration of inflammatory cells from blood into the airways.53,57,58,59 Since both eosinophils and macrophages express the adhesion molecule LFA‐1, this offers a potential target for modification of airway inflammation. Treatments other than statins targeted at reducing the expression of LFA‐1 have been effective in decreasing airway eosinophilia in a mouse model of allergic asthma,60 and have reduced sputum eosinophilia after allergen challenge in asthmatic patients.61 Since statins can inhibit LFA‐1/ICAM‐1 interaction, as seen in HIV,25 there is potential for statins to have an equivalent effect in asthma in which the pathophysiology is associated with eosinophil accumulation. Lovastatin has recently been shown to inhibit human alveolar epithelial production of IL‐8,62 which might also contribute a beneficial effect of statins in the treatment of neutrophil associated inflammatory diseases of the lungs.

The observation that statins increase eosinophil apoptosis in humans63 suggests a further therapeutic role. The mechanism of this is probably due to the rapid reduction of cellular expression of CD40 after statin administration and this strongly inhibits eosinophil survival.64 Similarly, the neutrophilia associated with a mouse model of acute lung injury is markedly reduced with lovastatin treatment,65 and this modulation of neutrophil apoptosis may prove beneficial in other inflammatory lung diseases, such as smokers with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) where neutrophils are present and where corticosteroid treatment may be of limited benefit. In addition to induction of apoptosis, statins (in this case lovastatin) also enhance the clearance of apoptotic cells by human and mouse macrophages, a statin‐specific effect reversible with mevalonate.66

Statins could affect the activation and proliferation of a variety of cells associated with lung inflammation. For example, statins suppress Th1 cell activation and IFN‐γ production, as seen in a recent trial in rheumatoid arthritis49 and, by analogy, this treatment could decrease the IFN‐γ dependent pathology of chronic asthma and pulmonary tuberculosis. Similarly, statins decrease natural killer (NK) cell activity in treated transplant patients,67 and this might be relevant to the pathogenesis of asthma in which NK cells may have a pathogenic role.68,69 The decrease in expression of MHC‐II induced by statins has been observed on monocytes, macrophages, and on B lymphocytes in mice,45 which implies a widespread downregulatory effect on presentation and immune response to inhaled or lung associated antigens.

Statins may also have a role in attenuating the tissue repair and remodelling consequences of chronic aberrant immune activation and inflammation. For example, statins inhibit the proliferation of human airway smooth muscle70 and lower the expression of the profibrogenic cytokine transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β1.71 Statins also reduce the tissue damage and cellular changes associated with cigarette smoking. The mechanism of this appears to be related to the reduction by statins of the production of matrix metalloprotease (MMP)‐9 and airway remodelling in smoking rats72 and rabbits,73 and in human macrophages74 and monocytes30 from smokers. Other MMPs may also be reduced.73,75,76,77 By targeting this key aspect of remodelling, this indicates a potential therapeutic role for statins in fibrotic lung diseases.

Finally, it is worth bearing in mind the different pharmacological properties between statins. For example, lovastatin seems to increase lymphocyte secretion of IL‐4 and IL‐5 in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis18 and therefore this particular statin may be of limited use in asthma where these cytokines are directly implicated in the pathogenesis.

Statin treatment of human and experimental respiratory diseases

Asthma

Atopic asthma is a chronic inflammatory condition of the airways characterised by airway hyperresponsiveness, inflammatory infiltrates in the bronchial walls containing lymphocytes and eosinophils, and elevated serum IgE levels. Th2 lymphocytes are thought to play a key role in the initiation and perpetuation of this airway inflammation,78,79,80 mediated by the functions of their signal cytokines such as IL‐3, IL‐4, IL‐5, and IL‐6. There is now evidence that Th1 cells may also contribute to disease,81,82 and IFN‐γ secretion may exacerbate airway inflammation in chronic asthma.83

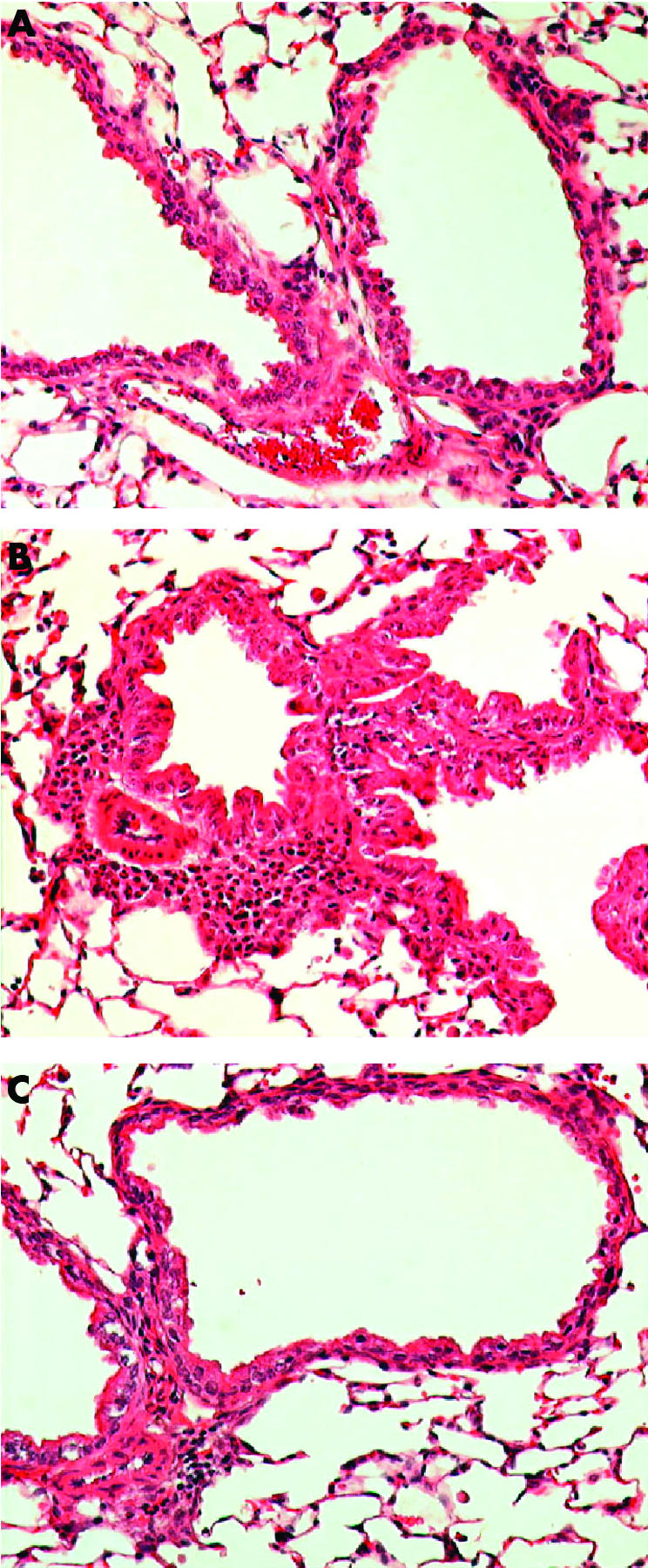

The potential benefits of statin therapy on inflammatory airway disease were demonstrated in a mouse model of allergic airways disease.84 In this model, airway eosinophilia was elicited using ovalbumin (OVA) as the allergen. Simvastatin given before each OVA challenge caused a reduction in inflammatory cell infiltrate and eosinophilia in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and a decrease in the OVA‐specific production of IFN‐γ, IL‐4 and IL‐5 by thoracic node lymphocytes in vitro (fig 3). The same anti‐inflammatory effects of pravastatin have been reported in a similar experimental model of allergic airway inflammation.85 The anti‐inflammatory properties of statins observed in animal models of allergic asthma84 and in smoking induced lung disease86 suggest that statin treatment could improve asthma control in smokers with asthma who are insensitive to treatment with corticosteroids.87

Figure 3 Histological evidence of decreased lung inflammation in mice treated with simvastatin. (A) Naive mouse given saline challenge. (B) Ovalbumin antigen challenged mouse showing peribronchial and perivascular inflammatory infiltrates with eosinophils and mucosal hyperplasia. (C) Ovalbumin challenged mouse treated with simvastatin showing a reduction in inflammatory infiltrates compared with (B). Stain: haematoxylin and eosin; magnification ×200. Reproduced with permission from McKay et al.84 © The American Association of Immunologists Inc, 2004.

COPD

In a rat model of smoking induced emphysema, Lee and co‐workers72 found that simvastatin inhibited lung parenchymal destruction and peribronchial and perivascular inflammatory cell infiltration. Induction of MMP‐9, a major inflammatory mediator, was reduced in the same model when the experiment was repeated using human lung microvascular endothelial cells in vitro. Pulmonary vascular remodelling was prevented and the decrease in endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression induced by smoking was inhibited.72 In a mouse model of emphysema, simvastatin reduced mRNA expression of IFN‐γ, TNF‐α and MMP‐12 in the whole lung and reduced the numbers of neutrophils and lymphocytes and the concentration of TNF‐α in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid,88 indicating reduced inflammation and remodelling.

Pulmonary hypertension

Experiments with rat pulmonary arterial fibroblasts indicate that statins decrease the normal proliferation in response to hypoxia.89 Statins also induce apoptosis of pulmonary vascular cells, mediated by inhibiting the prenylation of the small GTP‐binding proteins.90 This—in addition to an improvement in pulmonary artery pressure, ventricular and blood vessel remodelling, and polycythaemia seen in a rat model of pulmonary hypertension91—confers a significant survival advantage following treatment with simvastatin.72,92 An open label clinical case series of patients with pulmonary hypertension showed that simvastatin delays disease progression and may improve survival.93

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is an aggressive interstitial lung disease commonly affecting adults from middle age onwards. The prognosis is invariably poor, with a median survival of 3–5 years from diagnosis and no currently available efficacious treatment. Features of the pathogenesis of IPF are cell proliferation, collagen deposition, angiogenesis, and fibroblast differentiation into the profibrogenic myofibroblast phenotype.94 This is mediated through connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), an autocrine growth factor which is induced by TGF‐β1. Early experimental data suggest that simvastatin could modify critical determinants of the profibrogenic machinery responsible for the aggressive clinical profile of IPF, and could potentially prevent adverse lung parenchymal remodelling associated with persistent myofibroblast formation by inhibiting CTGF gene and protein expression and overriding the induction by TGF‐β1.95 This hypothesis has recently been tested in a clinical trial of lovastatin and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in IPF, but preliminary data showed no improvement in survival.96

Acute lung injury

In a model of acute lung injury, mice treated with simvastatin showed decreased lung permeability and a significant reduction in NF‐κB mediated gene transcription, suggesting a potential role for statins in the management of this disease.97 In this model the mice were exposed to aerosolised bacterial LPS followed by intratracheal keratinocyte derived chemokine, inducing an airspace neutrophil influx which was reduced by simvastatin. Reduced parenchymal myeloperoxidase and microvascular permeability, indicators of inflammation, were also seen with lovastatin, as well as reduced concentrations of pro‐inflammatory cytokines in airway fluid and serum.97

Ex vivo studies of neutrophils isolated from lovastatin treated mice confirmed that the inhibitory effects were statin dependent, affecting Rac activation, actin polymerisation, chemotaxis and bacterial killing. This anti‐inflammatory effect, which is beneficial to acute lung injury, may have detrimental effects on the normal antibacterial clearance mechanisms of the lung. For example, the innate pulmonary clearance of Klebsiella pneumoniae was inhibited by lovastatin and the blood dissemination of this organism was enhanced.97 In other words, lovastatin appears to decrease pulmonary inflammation but there may be an immunological cost in inhibiting host defence and promoting infection.65

Community acquired pneumonia

The concern for the possible adverse effect of statins in reducing resistance to lung infection was partly addressed in a retrospective cohort study of patients with community acquired pneumonia which showed that statins were associated with a 22% decrease in overall 30 day mortality (from 28% to 6%). This remained significant even after adjustment for potential confounders such as previous co‐morbidity which would normally be expected to increase mortality.98 However, there is still a need to monitor prospectively the effects of statin treatment on the immune response.

Lung transplantation

The outcomes in lung transplantation were compared between 39 patients taking statins for hyperlipidaemia (mainly atorvastatin and pravastatin) and 161 untreated controls. Acute rejection was less frequent, bronchoalveolar lavage showed lower total cellularity as well as lower proportions of neutrophils and lymphocytes, and survival was 91% compared with 54% in controls.99 This raises intriguing possibilities of an immunosuppressive role for statins, which suggests we are only beginning to explore the many applications for these drugs.

Conclusions

New drugs for the treatment of respiratory diseases are needed. The anti‐inflammatory properties of statins are numerous and complex and, although incompletely understood, there is tantalising evidence that they might prove to be of clinical benefit in the treatment of a range of inflammatory lung diseases. What is needed now is to extend the evidence of efficacy of statins in different inflammatory lung diseases, initially in the form of small scale proof‐of‐concept clinical trials. The choice of outcome measures used to assess efficacy will need to be carefully considered for each disease, since statins may influence biomarkers of inflammation to a greater extent than more conventional clinical end points. If the results of these clinical trials are encouraging, larger studies will be required to establish the effectiveness and adverse side effect profile of statin treatment in individual diseases.

Abbreviations

CCL2 - chemoattractant chemokine ligand 2

COPD - chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CRP - C‐reactive protein

CTGF - connective tissue growth factor

HMG‐CoA - 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme A

IFN‐γ - interferon γ

ICAM‐1 - intercellular adhesion molecule 1

IL - interleukin

IPF - idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

LFA‐1 - lymphocyte function associated antigen 1

LPS - lipopolysaccharide

MHC‐II - major histocompatibility complex class II

MMP - metalloprotease

NF‐κB - nuclear factor κB

NK - natural killer

TGF‐β - transforming growth factor β

TNF‐α - tumour necrosis factor α

Footnotes

This study was funded by Asthma UK.

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Pedersen T R. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 19943441383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaRosa J C, He J, Vupputuri S. Effect of statins on risk of coronary disease. A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 19992822340–2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepherd J, Cobbe S M, Ford I.et al Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolaemia. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Group. N Engl J Med 19953331301–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briel M, Studer M, Glass T R.et al Effects of statins on stroke prevention in patients with and without coronary heart disease: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Med 2004117596–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amarenco P, Labreuche J, Lavallee P.et al Statins in stroke prevention and carotid atherosclerosis: systematic review and up‐to‐date meta‐analysis. Stroke 2004352902–2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaughan C J, Murphy M B, Buckley B M. Statins do more than just lower cholesterol. Lancet 19963481079–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ridker P M, Rifai N, Pfeffer M A.et al Inflammation, pravastatin, and the risk of coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events (CARE) Investigators. Circulation 199898839–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albert M A, Danielson E, Rifai N.et al PRINCE Investigators. Effect of statin therapy on C‐reactive protein levels: the pravastatin inflammation/CRP evaluation, JAMA 200128664–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nissen S E, Tuzcu E M, Schoenhagen P.et al Statin therapy, LDL cholesterol, C‐reactive protein, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 200535229–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ridker P M, Cannon C P, Morrow D.et al C‐reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med 200535220–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danesh J, Collins R, Appleby P.et al Association of fibrinogen, C‐reactive protein, albumin, or leukocyte count with coronary heart disease: meta‐analyses of prospective studies. JAMA 19982791477–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jialal I, Devaraj S. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: the value of the high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein assay as a risk marker. Am J Clin Pathol 2001116S108–S115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeda U, Shimada K. Statins and monocytes. Lancet 19993532070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferro D, Parrotto S, Basili S.et al Simvastatin inhibits the monocyte expression of proinflammatory cytokinesin patients with hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 200036427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinrich P C, Castell J V, Andus T. Interleukin‐6 and the acute phase response. Biochem J 1990265621–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner A H, Kohler T, Ruckschloss U.et al Improvement of nitric oxide‐dependent vasodilatation by HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitors through attenuation of endothelial superoxide anion formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20002061–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehrenstein M R, Jury E C, Mauri C. Statins for atherosclerosis – as good as it gets? N Engl J Med 200535273–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nath N, Giri S, Prasad R.et al Potential targets of 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitor for multiple sclerosis therapy. J Immunol 20041721273–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwak B, Mulhaupt F, Myit S.et al Statins as a newly recognized type of immunomodulator. Nat Med 200061399–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mach F. Statins as novel immunomodulators: from cell to potential clinical benefit. Thromb Haemost 200390607–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura M, Kurose I, Russel J.et al Effects of fluvastatin on leucocyte‐endothelial cell adhesion in hypercholesterolemic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 199717e1521–e1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scalia R, Gooszen M E, Jones S P.et al Simvastatin exerts both anti‐inflammatory and cardioprotective effects on apolipoprotein E‐deficient mice. Circulation 20011032598–2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pruefer D, Scalia R, Lefer A M. Simvastatin inhibits leucocyte‐endothelial cell interactions and protects agains inflammatory processes in normocholesterolemic rats. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999192894–2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rice J B, Stoll L L, Li W G.et al Low‐level endotoxin induces potent inflammatory activation of human blood vessels: Inhibition by statins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2003231576–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giguere J F, Tremblay M J. Statin compounds reduce human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by preventing the interaction between virion‐associated host intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and its natural cell surface ligand LFA‐1. J Virol 20047812062–12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ni W, Egashira K, Kataoka C.et al Antiinflammatory and antiarteriosclerotic actions of HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitors in a rat model of chronic inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis. Circ Res 200189415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez‐Gonzalez J, Alfon J, Boerrozpe M.et al HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitors reduce vascular monocyte chemotactic protein‐1 expression in early lesions from hypercholesterolemic swine independently of their effect on plasma cholesterol levels. Atherosclerosis 200115927–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ikeda U, Shimada K. Statins and C‐reactive protein. Lancet 19993531274–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inoue I, Gotto S, Mizotani K.et al Lipophilic HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitor has an anti‐inflammatory effect: reduction of mRNA levels for interleukin‐1β, interleukin‐6, cyclooxygenase‐2, and p22phox by regulation of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor α (PPARα) in primary endothelial cells. Life Sci 200067863–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grip O, Janciauskiene S, Lindgren S. Atorvastatin activates PPAR‐γ and attenuates the inflammatory response in human monocytes. Inflamm Res 20025158–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seeger H, Mueck A O, Lippert T H. Fluvastatin increases prostacyclin and decreases endothelin production by human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 200038270–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernandez‐Perera O, Perez‐Sala D, Navarro‐Antolin J.et al Effects of the 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, atorvastatin and simvastatin, on the expression of endothelin‐1 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular endothelial cells. J Clin Invest 19981012711–2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newton C J, Ran G, Xie Y X.et al Statin‐induced apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells is blocked by dexamethasone. J Endocrinol 20021747–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van de Donk N W C J, Kamphuis M M J, van Kessel B.et al Inhibition of protein geranylgeranylation induces apoptosis in myeloma plasma cells by reducing Mcl‐1 protein levels. Blood 20031023354–3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudich S M, Mongini P K A, Perez R V.et al HMG‐CoA reducatse inhibitors pravastatin and simvastatin inhibit human B‐lymphocyte activation. Transplant Proc 199830992–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chakrabarti R, Engleman E G. Interrelationships between mevalonate metabolism and the mitogenic signaling pathway in T lymphocyte proliferation. J Biol Chem 199126612216–12222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hakamada‐Taguchi R, Uehara Y, Kuribayashi K.et al Inhibition of hydroxymethylglutaryl‐coenzyme a reductase reduces Th1 development and promotes Th2 development. Circ Res 200393948–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown R D, Ambler S K, Mitchell M D.et al The cardiac fibroblast: therapeutic target in myocardial remodeling and failure. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 200545657–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shishehbor M H, Brennan M L, Aviles R J.et al Statins promote potent systemic antioxidant effects through specific inflammatory pathways. Circulation 2003108426–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rikitake Y, Kawashima S, Takeshita S.et al Anti‐oxidative properties of fluvastatin, an HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitor, contribute to prevention of atherosclerosis in cholesterol‐fed rabbits. Atherosclerosis 200115487–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aviram M, Rosenblat M, Bisgaier C L.et al Atorvastatin and gemfibrozil metabolites, but not the parent drugs, are potent antioxidants against lipoprotein oxidation. Atherosclerosis 1998138271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamamoto A, Hoshi K, Ichihara K. Fluvastatin, an inhibitor of 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl conenzyme A reductase, scavenges free radicals and inhibits lipid peroxidation in rat liver microsomes. Eur J Pharmacol 1998361143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wassmann S, Laufs U, Muller K.et al Cellular antioxidant effects of atorvastatin in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 200222300–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Girona J, La Ville A E, Sola R.et al Simvastatin decreases aldehyde production derived from lipoprotein oxidation. Am J Cardiol 199983846–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lawman S, Mauri C, Jury E C.et al Atorvastatin inhibits autoreactive B cell activation and delays lupus development in New Zealand black/white F1 mice. J Immunol 20041737641–7646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi M, Rolle S, Rane M.et al Extracellular signal‐regulated kinase inhibition by statins inhibits neutrophil activation by ANCA. Kidney Int 20036396–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leung B P, Sattar N, Crilly A.et al A novel anti‐inflammatory role for simvastatin in inflammatory arthritis. J Immunol 20031701524–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gegg M E, Harry R, Hankey D.et al Suppression of autoimmune retinal disease by lovastatin does not require Th2 cytokine induction. J Immunol 20051742327–2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCarey D W, McInnes I B, Madhok R.et al Trial of atorvastatin in rheumatoid arthritis (TARA): double‐blind, randomised placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet 20043632015–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kiener P A, Davis P M, Murray J L.et al Stimulation of inflammatory responses in vitro and in vivo by lipophilic HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitors. Int Immunopharmacol 20011105–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knapp A C, Huang J, Starling G.et al Inhibitors of HMG‐CoA reductase sensitize human smooth muscle cells to Fas‐ligand and cytokine‐induced cell death. Atherosclerosis 2000152217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hilgendorff A, Muth H, Parviz B.et al Statins differ in their ability to block NFκB activation in human blood monocytes. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 200341397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takahashi H K, Mori S, Iwagaki H.et al Differential effect of LFA703, pravastatin, and fluvastatin on production of IL‐18 and expression of ICAM‐1 and CD40 in human monocytes. J Leukoc Biol 200577400–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenson R S, Tangney C C, Casey L C. Inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine production by pravastatin. Lancet 1999353983–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wagner A H, Schwabe O, Hecker M. Atorvastatin inhibition of cytokine‐inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in native endothelial cells in situ. Br J Pharmacol 2002136143–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fehr T, Kahlert C, Fierz W.et al Statin‐induced immunomodulatory effects on human T cells in vivo. Atherosclerosis 200417583–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nishibori M, Takahashi H K, Mori S. The regulation of ICAM‐1 and LFA‐1 interaction by autacoids and statins: a novel strategy for controlling inflammation and immune responses. J Pharmacol Sci 2003927–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watkins A D, Hatfield C A, Fidler S F.et al Phenotypic analysis of airway eosinophils and lymphocytes in a Th‐2‐driven murine model of pulmonary inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 19961520–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watanabe T, Fan J. Atherosclerosis and inflammation mononuclear cell recruitment and adhesion molecules with reference to the implication of ICAM‐1/LFA‐1 pathway in atherogenesis. Int J Cardiol 199866S45–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Winn M, Reilly E B, Liu G.et al Discovery of novel p‐arylthio cinnamides as antagonists of leucocyte function‐associated antigen‐1/intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 interaction. 4. Structure‐activity relationship of substituents on the benzene ring of the cinnamide. J Med Chem 2001444393–4403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gauvreau G M, Becker A B, Boulet L P.et al The effects of an anti‐CD11a mAb, efalizumab, on allergen‐induced airway and airway inflammation in subjects with atopic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003112331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hayden J M, Swartfiguer J, Szelinger S.et al Lysophosphatidylcholine stimulation of alveolar epithelial cell interleukin‐8 production and neutrophil chemotaxis is inhibited by statin treatment. Proc Am Thor Soc 20052A72 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Luo F. Simvastatin induces eosinophil apoptosis in vitro. Chest 2004126721S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bureau F, Seumois G, Jaspar F.et al CD40 engagements enhances eosinophil survival through induction of cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 2 expression: possible involvement in allergic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002110443–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fessler M B, Young S K, Jeyaseelan S.et al A role for hydroxy‐methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase in pulmonary inflammation and host defense. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005171606–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morimoto K, Janssen W J, Fessler M B.et al HMG Co‐A reductase inhibitors (statins) enhance clearance of apoptotic cells in vitro and in vivo. Proc Am Thor Soc 20052A902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Katznelson S, Wang X M, Chia D.et al The inhibitory effects of pravastatin on natural killer cell activity in vivo and on cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity in vitro. J Heart Lung Transplant 199817335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wei H, Zhang J, Xiao W.et al Involvement of human natural killer cells in asthma pathogenesis: natural killer 2 cells in type 2 cytokine predominance. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005115841–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kronenberg M, Rudensky A. Regulation of immunity by self‐reactive T cells. Nature 2005435598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Takeda N, Kume H, Ito S.et al Rho is involved in the inhibitory effects of simvastatin on proliferation of human airway smooth muscle cells (abstract). Eur Respir J . 2005;26 (Suppl 49)223s

- 71.Qin J, Zhang Z, Liu J.et al Effects of the combination of an angiotensin II antagonist with an HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitor in experimental diabetes. Kidney Int 200364565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee J ‐ H, Lee D ‐ S, Kim E ‐ K.et al Simvastatin inhibits cigarette smoking‐induced emphysema and pulmonary hypertension in rat lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005172987–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fukumoto Y, Libby P, Rabkin E.et al Statins alter smooth muscle cell accumulation and collagen content in established atheroma of Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbits. Circulation 2001103993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bellosta S, Via D, Canavesi P.et al HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitors reduce MMP‐9 secretion by macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1998181671–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ikeda U, Shimpo M, Ohki R.et al Fluvastatin inhibits matrix metalloproteinase‐1 expression in human vascular endothelial cells. Hypertension 200036325–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aikawa M, Rabkin E, Sugiyama S.et al An HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitor, cerivastatin, suppresses growth of macrophages expressing matrix metalloproteinases and tissue factor in vivo and in vitro. Circulation 2001103276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lazzerini P E, Capecchi P L, Nerucci F.et al Simvastatin reduces MMP‐3 level in interleukin‐1β stimulated human chondrocyte culture. Ann Rheum Dis 200463867–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Holt P G, McCaubus C, Stumbles P A.et al The role of allergy in the development of asthma. Nature 1999402B12–B17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Robinson D S, Hamid Q, Ying S.et al Predominant Th2‐like bronchoalveolar T‐lymphocyte population in atopic asthma. N Engl J Med 1992326298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barnes P J, Chung K F, Page C P. Inflammatory mediators of asthma. Pharmacol Rev 199850515–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hansen G, Berry G, DeKruyff R H.et al Allergen‐specific Th1 cells fail to counterbalance Th2 cell‐induced airway hyperreactivity but cause severe airway inflammation. J Clin Invest 1999103175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Randolph D A, Carruthers C J, Szabo S J.et al Modulation of airway inflammation by passive transfer of allergen‐specific Th1 and Th2 cells in a mouse model of asthma. J Immunol 19991622375–2383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cohn L, Homer R J, Niu N.et al T helper 1 cells and interferonχ regulate allergic airway inflammation and mucus production. J Exp Med 19991901309–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McKay A, Leung B P, McInnes I B.et al A novel anti‐inflammatory role of simvastatin in a murine model of allergic asthma. J Immunol 20041722903–2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yeh Y F, Huang S L. Enhancing effect of dietary cholesterol and inhibitory effect of pravastatin on allergic pulmonary inflammation. J Biomed Sci 200411599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lee J ‐ H, Lee D ‐ S, Kim E ‐ K.et al Simvastatin inhibits cigarette smoking‐induced emphysema and pulmonary hypertension in rat lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005172987–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thomson N C, Chaudhuri R, Livingston E. Asthma and cigarette smoking. Eur Respir J 200424822–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Takahashi S, Nakamura H, Furuuchi M.et al Simvastatin suppresses the development of elastase‐induced emphysema in mice (abstract). Proc Am Thor Soc 20052A135 [Google Scholar]

- 89.Carlin C M, Peacock A J, Welsh D J. Statins inhibit hypoxic proliferation of pulmonary artery fibroblasts: potential for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension (abstract). Thorax 200560(Suppl II)ii4 [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stark W W J, Blaskovich M A, Johnson B A.et al Inhibiting geranylgeranylation blocks growth and promotes apoptosis in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol 1998275L55–L63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Girgis R E, Li D, Zhan X.et al Attenuation of chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension by simvastatin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003285H938–H945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nishimura T, Vaszar L T, Faul J L.et al Simvastatin rescues rats from fatal pulmonary hypertension by inducing apoptosis of neointimal smooth muscle cells. Circulation 20031081640–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kao P N. Simvastatin treatment of pulmonary hypertension: an observational case series. Chest 20051271446–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Khalil N, Bereznay O, Sporn M.et al Macrophage production of transforming growth factor beta and fibroblast collagen synthesis in chronic pulmonary inflammation. J Exp Med 1989170727–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Watts K L, Sampson E M, Schultz G S.et al Simvastatin inhibits growth factor expression and modulates profibrogenic markers in lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 200532290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nadrous H F, Ryu J H, Douglas W W.et al Impact of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors and statins on survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2004126438–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jacobson J R, Barnard J W, Grigiryev D N.et al Simvastatin attenuates vascular leak and inflammation in murine inflammatory lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005288L1026–L1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mortensen E M, Restrepo M I, Anzueto A.et al The effect of prior statin use on 30‐day mortality for patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia. Respir Res 2005682–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Johnson B A, Iacono A T, Zeevi A.et al Statin use is associated with improved function and survival of lung allografts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20031671271–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]