Abstract

Ophiostoma species have diverse morphological features and are found in a large variety of ecological niches. Many different classification schemes have been applied to these fungi in the past based on teleomorph and anamorph features. More recently, studies based on DNA sequence comparisions have shown that Ophiostoma consists of different phylogenetic groups, but the data have not been sufficient to define clear monophyletic lineages represented by practical taxonomic units. We used DNA sequence data from combined partial nuclear LSU and β-tubulin genes to consider the phylogenetic relationships of 50 Ophiostoma species, representing all the major morphological groups in the genus. Our data showed three well-supported, monophyletic lineages in Ophiostoma. Species with Leptographium anamorphs grouped together and to accommodate these species the teleomorph-genus Grosmannia (type species G. penicillata), including 27 species and 24 new combinations, is re-instated. Another well-defined lineage includes species that are cycloheximide-sensitive with short perithecial necks, falcate ascospores and Hyalorhinocladiella anamorphs. For these species, the teleomorph-genus Ceratocystiopsis (type species O. minuta), including 11 species and three new combinations, is re-instated. A third group of species with either Sporothrix or Pesotum anamorphs includes species from various ecological niches such as Protea infructescences in South Africa. This group also includes O. piliferum, the type species of Ophiostoma, and these species are retained in that genus. Ophiostoma is redefined to reflect the changes resulting from new combinations in Grosmannia and Ceratocystiopsis. Our data have revealed additional lineages in Ophiostoma linked to morphological characters. However, these species are retained in Ophiostoma until further data for a larger number of species can be obtained to confirm monophyly of the apparent lineages.

Keywords: Ceratocystiopsis, Grosmannia, Ophiostoma, phylogenetics

INTRODUCTION

Considerable confusion has surrounded the taxonomy of the so-called ophiostomatoid fungi ever since the first descriptions of Ophiostoma Syd. & P. Syd. and Ceratocystis Ellis & Halst. (Table 1). The majority of these fungi are specifically adapted for dispersal by insects, they resemble each other morphologically and they typically share similar niches linked to their biological characteristics. During the course of the last decade, phylogenetic studies based on DNA sequence comparisons have been applied to these fungi and they confirmed suggestions (De Hoog 1974, Von Arx 1974, Weijman & De Hoog 1975, Harrington 1981, 1984) that the two keystone genera, Ophiostoma and Ceratocystis, have polyphyletic origins (Hausner et al. 1992, 1993b,c, Spatafora & Blackwell 1994). Species sensitive to the antibiotic cycloheximide, and with Thielaviopsis Went anamorphs and endoconidia arising from ring wall-building conidium development (Minter et al. 1983), clearly reside in Ceratocystis in the order Microascales Luttrell ex Benny & Kimbr. (Hausner et al. 1993b, Spatafora & Blackwell 1994, Paulin-Mahady et al. 2002). Species tolerant to cycloheximide, containing rhamnose and cellulose in their cell walls, and with anamorphs residing in Sporothrix Hektoen & C.F. Perkins, Hyalorhinocladiella H.P. Upadhyay & W.B. Kendr., Leptographium Lagerb. & Melin, or Pesotum J.L. Crane & Schokn. emend. G. Okada & Seifert, reside in Ophiostoma in the Ophiostomatales Benny & Kimbr. (Hausner et al. 1993c, Spatafora & Blackwell 1994). Application of this definition for Ophiostoma results in more than 140 species, exhibiting a large variety of distinct teleomorph and anamorph features.

Table 1.

Definition of genera of the ophiostomatoid fungi as applied by different authors.

Teleomorph characters applied in taxonomic studies of Ophiostoma include the shape and size of the ascomata and ascospores, and the presence or absence of sheaths surrounding the ascospores. The majority of Ophiostoma spp. have ascomata with long necks giving rise to masses of sticky ascospores adapted for dispersal by insects (Upadhyay 1981, Harrington 1987, Jacobs & Wingfield 2001). In 1957, Parker described the genus Europhium A.K. Parker for a species that exhibits all the characters of Ophiostoma, but with ascocarps cleistothecial, lacking necks and ostioles (Parker 1957). Subsequently three additional species were described in Europhium (Robinson-Jeffrey & Davidson 1968). All four of the species were eventually transferred to Ophiostoma (Harrington 1987) because the formation or length of necks, and the presence of an ostiole, might be affected by the environment and were considered `less reliable' taxonomic characters (Upadhyay 1981). A number of phylogenetic studies confirmed that these species are closely related to Ophiostoma spp. with Leptographium anamorphs (Hausner et al. 2000, Lim et al. 2004).

Ophiostoma spp. have ascospores with unusual shapes. Several studies have applied this characteristic to define groups within the genus, which at the time of these studies was treated as a synonym of Ceratocystis (Wright & Cain 1961, Griffin 1968, Olchowecki & Reid 1973, Upadhyay 1981). For species that have falcate ascospores with sheaths and short perithecial necks, Upadhyay & Kendrick (1975) established Ceratocystiopsis H.P. Upadhyay & W.B. Kendr. However, Wingfield (1993) argued that ascospore shape should not be the sole character to delineate genera, and that it was illogical to maintain Ceratocystiopsis as a separate genus because Ophiostoma contained many species with a variety of other, distinct ascospore forms. He thus suggested that Ceratocystiopsis should be treated as a synonym of Ophiostoma and that ascospore morphology should only be one of several characteristics on which to base further subdivisions in the genus. Hausner et al. (1993a) proceeded to formally reduce Ceratocystiopsis to synonymy with Ophiostoma, based on partial SSU and LSU rDNA sequences. These authors included 10 Ceratocystiopsis spp., but only one Ophiostoma (O. ips (Rumbold) Nannf.) and one Ceratocystis (C. fimbriata Ellis & Halst.) species in the phylogenetic analysis of the data. Phylogenetic studies involving other ascomycete genera confirmed that ascospore morphology should not be used as the only character for taxonomic grouping as similar ascospore shapes often originated more than once in a genus (Hausner et al. 1992, Wingfield et al. 1994).

The diversity of the anamorphs associated with Ophiostoma established anamorph morphology as a preferred characteristic to group species in the genus (Münch 1907, Melin & Nannfeldt 1934, Hunt 1956, Davidson 1958, Mathiesen-Käärik 1960). However, this approach is complicated by the fact that a significant number of Ophiostoma spp. produce not only one, but combinations of up to three of the four possible anamorph states associated with the genus (De Hoog 1974, Okada et al. 1998). Ophiostoma ips, for example, has a continuum of synanamorph states, which based on current definitions range from Hyalorhinocladiella-like and Leptographium-like to Pesotum (Seifert et al. 1993). The anamorphs of just this one species have previously been classified in Graphium (Leach et al. 1934), Scopularia Preuss (Goidánich 1936), Cephalosporium auct. non Corda (Moreau 1952), Leptographium (Moreau 1952), Hyalorhinocladiella (Upadhyay 1981), Graphilbum H.P. Upadhyay & W.B. Kendr. (Upadhyay 1981), Acremonium Link: Fr. (Hutchison & Reid 1988), and Pesotum (Okada et al. 1998).

The only case where a teleomorph-genus has specifically been erected to accommodate Ophiostoma spp. based on a common anamorph, was when Goidánich (1936) established Grosmannia Goid. for four species with Leptographium anamorphs. He first described Grosmania invalidly, without a Latin description (Goidánich 1935). Later Goidánich validated the genus and at the same time corrected the spelling to Grosmannia (Goidánich 1936). Siemaszko (1939) reduced Grosmannia to synonymy with Ophiostoma on the basis of teleomorph morphology. Grosmannia has been treated in all subsequent studies as synonym of either Ophiostoma (Mathiesen 1951, Von Arx 1952, De Hoog 1974, Von Arx 1974, Seifert et al. 1993, Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) or Ceratocystis (Bakshi 1951, Moreau 1952, Hunt 1956, Davidson 1958, Griffin 1968, Upadhyay 1981). Phylogenetic studies have placed three of the original four Grosmannia species, G. serpens Goid., G. penicillata (Grosmann) Goid. and G. ips (Rumbold) Goid., in Ophiostoma (Hausner et al. 2000, Jacobs et al. 2001, Zhou et al. 2004a, 2005). The fourth species, G. pini (Münch) Goid., has been treated as a synonym of O. minus (Hedgc.) Syd. & P. Syd. (Moreau 1952, Hunt 1956, Griffin 1968, Olchowecki & Reid 1973, Upadhyay 1981) which, based on phylogeny, also resides in Ophiostoma (Gorton et al. 2004).

Amongst the four anamorph-genera associated with Ophiostoma spp., Sporothrix appears to be the most common form, with conidia produced sympodially on denticles arising from undifferentiated hyphae (De Hoog 1974). This is also the form that occurs most often as a synanamorph of Pesotum spp. (Crane & Schoknecht 1973, De Hoog 1974, Okada et al. 1998, Harrington et al. 2001). The original description of Pesotum included mononematous conidiophores and conidiogenous cells with prominent denticles, thus the Sporothrix-like component of the anamorph (Crane & Schoknecht 1973). In a study showing that Graphium is phylogenetically distinct from the synnematal anamorphs of Ophiostoma spp., and where Pesotum was redefined to encompass all synnematous anamorphs of Ophiostoma, only the synnematous form was described (Okada et al. 1998). The Sporothrix form was thus treated as a distinct synanamorph of Pesotum (Okada et al. 1998). However, Harrington et al. (2001) accepted the original description of Pesotum, which included the Sporothrix-like forms, but restricted the genus to anamorphs with affinities to the O. piceae complex. Harrington et al. (2001) also stated that the synnemata of Ophiostoma spp. outside the O. piceae complex are loose aggregates of Leptographium conidiophores, without the fused stipe cells that are characteristic of the O. piceae complex. These synnematous species outside the O. piceae complex often lack a Sporothrix anamorph, although some species produce a mononematous form without prominent denticles, resembling Hyalorhinocladiella. Hyalorhinocladiella was described for the mononematous anamorphs of Ceratocystiopsis and Ophiostoma (Upadhyay & Kendrick 1975), where conidia are produced through sympodial proliferation, leaving flat, ring-like scars on the surface of conidiogenous cells, as opposed to the denticles visible in Sporothrix spp. (Mouton et al. 1994, Benade et al. 1996). Although these anamorph-genera can be defined broadly, the delimitation of species groups based on anamorph morphology remains problematic, especially because of intermediate and overlapping forms.

Phylogenetic studies have substantially improved the ability to delimit species within almost all the morphological groups (based on ascospores and anamorphs) of the genus Ophiostoma (Harrington et al. 2001, De Beer et al. 2003, Jacobs & Kirisits 2003, Kim et al. 2003, Gorton et al. 2004, Lim et al. 2004, Zhou et al. 2004b). In the more recent of these studies, multigene approaches employing ribosomal together with protein-coding genetic data have become the norm. The morphological divergence in Ophiostoma strongly suggests that some of the morphological traits must be represented by monophyletic lineages. However, phylogenetic studies that have all been based on partial ribosomal DNA data have failed to support the definition of monophyletic lineages in Ophiostoma (Hausner et al. 1993b, 2000, Jacobs et al. 2001, Hausner & Reid 2003). In this investigation we reconsider the view that Ophiostoma might be logically subdivided based on monophyly. This is achieved using DNA sequences from domains 1 and 2 of the 5' end of the nuclear LSU gene, together with partial sequences for the β-tubulin gene region. Fifty species of Ophiostoma representing all the ascospore forms and anamorph shapes associated with the genus are included in the study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates

Isolates used in this study (Table 2) are maintained at the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS), Utrecht, The Netherlands, as well as in the culture collection (CMW) of the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI) at the University of Pretoria, South Africa. Cultures were grown on malt extract agar (MEA, 2 % malt extract [Biolab, Merck] and 2 % agar [Biolab, Merck]) at 21–24 °C for DNA extraction.

Table 2.

Species and origin of strains included in this study.

| Species | CBS noa | CMW nob | Substrate/Host | Origin | Collector | Anamorph | Ascospore shape | Sheath |

GenBank no

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSU | β-tubulin | |||||||||

| Leptographium lundbergii | CBS 352.29 | 217 | Pinus sp. | Europe | M. Lagerberg | Leptographium (Hedgcock 1906) | no teleomorph (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | - | DQ294388 | DQ296108 |

| L. truncatum | CBS 118584 | 29 | Pinus taeda | South Africa | M.J. Wingfield | Leptographium (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | no teleomorph (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | - | DQ294390 | DQ296110 |

| L. wageneri var. wageneri | CBS 119492 | 1827 | Pinus monophylla | U.S.A. | T. Harrington | Leptographium (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | bean-shaped (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | n | DQ294397 | DQ296117 |

| Ophiostoma aenigmaticumc | CBS 501.96 | 2199 | Picea jezoensis | Japan | Y. Yamaoka | Leptographium (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | cucullate, hat-shaped (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | y | DQ294391 | DQ296111 |

| O. africanum | CBS 116571 | 823 | Protea gaguedi | South Africa | M.J. Wingfield | Sporothrix (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | lunate (Marais & Wingfield 2001) | n | AF221015d | DQ296073 |

| O. ainoae | CBS 118672 | 1903 | Picea abies | Norway | O. Olsen | Pesotum (Marais & Wingfield 2001) | cylindrical (Solheim 1986) | y | DQ294368 | DQ296088 |

| O. aureum | CBS 438.69e | 667 | Pinus contorta var. latifolia | Canada | R.W. Davidson | Leptographium (Solheim 1986) | cucullate, hat-shaped (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | y | DQ294389 | DQ296109 |

| O. araucariae | CBS 114.68e | 671 | Araucaria sp. | Chile | H. Butin | Pesotum (Robinson-Jeffrey & Davidson 1968) | ovoid to cylindrical (Okada et al. 1998) | n | DQ294373 | DQ296093 |

| O. canum | CBS 118668 | 5023 | Tomicus minor | Austria | T. Kirisits | Pesotum (Butin 1968) | orange section (Harrington et al. 2001) | n | DQ294372 | DQ296092 |

| O. carpenteri | CBS 118670 | 13793 | Trypodendron lineatum | U.S.A. | S.E. Carpenter | Sporothrix-like (Mathiesen 1951) | narrowly clavate, straight or curved (Hausner et al. 2003) | n | DQ294363 | DQ296083 |

| O. crassivaginatum | CBS 119144 | 134 | unknown | unknown | T. Hinds | Leptographium (Hausner et al. 2003) | fusiform (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | y | DQ294386 | DQ296106 |

| O. distortum | CBS 397.77 | 467 | ambrosia beetle gallery in Picea engelmannii | U.S.A. | R.W. Davidson | Sporothrix (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | orange section (Seifert et al. 1993) | n | DQ294369 | DQ296089 |

| O. flexuosum | CBS 208.83e | 907 | Picea abies | Norway | H. Solheim | Sporothrix (Davidson 1971) | cylindrical to ossiform (Solheim 1986) | y | DQ294370 | DQ296090 |

| O. floccosum | 1713 | Pinus ponderosa | U.S.A. | C. Bertagnole | Pesotum (Solheim 1986) | kidney-shaped (Harrington et al. 2001) | n | DQ294367 | DQ296087 | |

| O. francke-grosmanniae | CBS 118671 | 2975 | Larix sp. | U.S.A. | M.J. Wingfield | Leptographium (Mathiesen 1951) | hat-shaped, cucullate (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | y | DQ294395 | DQ296115 |

| O. fusiforme | CBS 112912e | 9968 | Populus nigra | Azerbaijan | D.N. Aghayeva | Sporothrix (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | allantoid (Aghayeva et al. 2004) | n | DQ294354 | AY28461d |

| O. galeiforme | CBS 115711 | 5290 | Pinus sylvestris | Scotland | T. Kirisits | Leptographium (Aghayeva et al. 2004) | hat-shaped, bean-shaped (Zhou et al. 2004b) | y | DQ294383 | DQ296103 |

| O. grandifoliae | CBS 119679 | 703 | Fagus grandifolia | U.S.A. | R.W. Davidson | Leptographium (Zhou et al. 2004b) | allantoid (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | y | DQ294399 | DQ296119 |

| O. huntii | CBS 153.65e | 2808 | Pinus contorta | Canada | R.C. Robinson-Jeffrey | Leptographium (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | curved (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | y | DQ294387 | DQ296107 |

| O. ips | CBS 137.36e | 7075 | Ips integer | U.S.A. | C.T. Rumbold | Pesotuml Leptographiuml Hyalorhinocladiella (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | pillow-shaped (Seifert et al. 1993) | y | DQ294381 | DQ296101 |

| O. laricis | 1913 | Larix sp. | Japan | Y. Yamaoka | Leptographium (Rumbold 1936) | curved (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | y | DQ294393 | DQ296113 | |

| O. leptographioides | CBS 144.59 | 481 | unknown | U.S.A. | R.W. Davidson | Leptographium (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | hat-shaped, reniforn (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | y | DQ294382 | DQ296102 |

| O. lunatum | CBS 112928 | 10564 | Larix decidua | Austria | T. Kirisits | Sporothrix (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | allantoid (Aghayeva et al. 2004) | n | DQ294355 | AY280467d |

| O. manitobensef | CBS 118838 | 13792 | bark of Pinus resinosa | Canada | J. Reid | Hyalorhinocladiellag (Aghayeva et al. 2004) | falcate (Hausner et al. 2003) | y | DQ294358 | DQ296078 |

| O. minimum | CBS 182.86 | 162 | Pinus banksiana | U.S.A. | M.J. Wingfield | Hyalorhinocladiella (Hausner et al. 2003) | falcate (Upadhyay 1981) | y | DQ294361 | DQ296081 |

| O. minutum | CBS 119682 | 4586 | Ips cembrae | Scotland | T. Kirisits | Hyalorhinocladiella (Upadhyay 1981) | falcate (Upadhyay 1981) | y | DQ294360 | DQ296080 |

| O. minutum-bicolor | CBS 393.77 | 1018 | Ips gallery in Pinus | U.S.A. | R.W. Davidson | Hyalorhinocladiella (Siemaszko 1939) | falcate (Upadhyay & Kendrick 1975) | y | DQ294359 | DQ296079 |

| O. montium | CBS 151.78 | 13221 | Dendroctonus ponderosae gallery in P. ponderosa | U.S.A. | R.W. Davidson | Pesotum (= Graphilbum) / Hyalorhinocladiella (Olchowecki & Reid 1973) | pillow-shaped (Upadhyay 1981) | y | DQ294379 | DQ296099 |

| O. multiannulatum | CBS 357.77 | 2567 | Pinus sp. | U.S.A. | unknown | Sporothrix (Rumbold 1941) | reniform (De Hoog 1974) | n | DQ294366 | DQ296086 |

| O. nigrocarpum | CBS 638.66e | 651 | Pseudotsuga menziesii | U.S.A. | R.W. Davidson | Sporothrix (Davidson 1935) | crescent-shaped (De Hoog 1974) | n | DQ294356 | AY280480d |

| O. novo-ulmi | CBS 119476 | 10573 | Picea abies | Austria | Neumuller | Pesotum (Davidson 1966) | orange section (Harrington et al. 2001) | n | DQ294375 | DQ296095 |

| O. penicillatum | CBS 140.36e | 470 | Picea abies | Germany | H. Grosmann | Leptographium (Brasier 1991) | allantoid (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | y | DQ294385 | DQ296105 |

| O. penicillatum | CBS 116008 | 2644 | wood from Picea abies | Norway | H. Solheim | Leptographium (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | allantoid (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | y | DQ294384 | DQ296104 |

| O. piceae | CBS 119678 | 8093 | Tetropium sp. | Canada | K. Harrison | Pesotum (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | lunate (Harrington et al. 2001) | n | DQ294371 | DQ296091 |

| O. piceiperdum | CBS 366.75 | 660 | Picea abies | Finland | A.M. Hallakselä | Leptographium | cucullate | y | DQ294392 | DQ296112 |

| O. piliferum | CBS 129.32 | 7879 | Pinus sylvestris | unknown | H. Diddens | Sporothrix (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | orange section (De Hoog 1974) | n | DQ294377 | DQ296097 |

| O. piliferum | CBS 118835 | 7877 | unknown | unknown | unknown | Sporothrix (Upadhyay 1981) | orange section (De Hoog 1974) | n | DQ294378 | DQ296098 |

| O. pluriannulatum | CBS 118684 | 75 | unknown | unknown | R.W. Davidson | Sporothrix (Upadhyay 1981) | reniform (Seifert et al. 1993) | n | DQ294365 | DQ296085 |

| O. protearum | CBS 116568 | 1102 | Protea caffra | South Africa | M.J. Wingfield | Sporothrix (Hedgcock 1906) | lunate (Marais & Wingfield 1997) | n | AF221014d | DQ296072 |

| O. pulvinisporum | CBS 118673e | 9022 | Pinus pseudostrobus | Mexico | X. Zhou | Hyalorhinocladiella / Leptographium / Pesotum (Marais & Wingfield 1997) | pillow-shaped (Zhou et al. 2004a) | y | DQ294380 | DQ296100 |

| O. quercus | CBS 118713 | 3110 | Juglans cinerea | U.S.A. | M.J. Wingfield | Pesotum (Zhou et al. 2004a) | reniform (Harrington et al. 2001) | n | DQ294376 | DQ296096 |

| O. ranaculosum | CBS 119683 | 13940 | Pinus echinata | U.S.A. | F. Hains | Sporothrix (Georgévitch 1926) | falcate (Bridges & Perry 1987) | y | DQ294357 | DQ296077 |

| O. robustum | CBS 119480 | 2805 | unknown | unknown | T. Hinds | Leptographium (Bridges & Perry 1987) | hat-shaped, reniform (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | y | DQ294398 | DQ296118 |

| O. rollhansenianum | CBS 118669 | 13791 | beetle galleries in Pinus sylvestris | Norway | J. Reid | Hyalorhinocladiellag (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | falcate (Hausner et al. 2003) | y | DQ294362 | DQ296082 |

| O. serpens | CBS 641.76 | 290 | Pinus pinea | Italy | Gambogi | Leptographium (Hausner et al. 2003) | ellipsoid (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | y | DQ294394 | DQ296114 |

| O. splendens | CBS 116569 | 872 | Protea repens | South Africa | M.J. Wingfield | Sporothrix (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | lunate (Marais & Wingfield 1994) | n | AF221013d | DQ296071 |

| O. stenoceras | CBS 237.32e | 3202 | pine pulp | Norway | H. Robak | Sporothrix (Marais & Wingfield 1994) | orange section (De Hoog 1974) | n | DQ294350 | DQ296074 |

| O. subannulatum | CBS 118667 | 518 | Pinus ponderosa | unknown | W. Livingston | Sporothrix (Robak 1932) | allantoid to broadly lunate (Livingston & Davidson 1987) | n | DQ294364 | DQ296084 |

| O. ulmi | CBS 119479 | 1462 | Ulmus procera | U.S.A. | C. Brasier | Pesotum (Livingston & Davidson 1987) | elongate orange section (Harrington et al. 2001) | n | DQ294374 | DQ296094 |

| O. wageneri | CBS 118845 | 491 | Pinus jeffreyi | unknown | T. Harrington | Leptographium (Buisman 1932) | bean-shaped (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | n | DQ294396 | DQ296116 |

| Sporothrix inflata | CBS 239.68e | 12527 | soil | Germany | W. Gams | Sporothrix (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001) | no teleomorph | - | DQ294351 | DQ296075 |

| S. schenckii | CBS 117842 | 7614 | human sporotrichosis | South Africa | H. Vismer | Sporothrix (De Hoog 1974) | no teleomorph | - | DQ294352 | AY280477d |

| CBS 119145 | 17137 | horse | South Africa | J.A. Picard | Sporothrix (De Hoog 1974) | no teleomorph | - | DQ294353 | DQ296076 | |

CBS = Culture Collection of the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

CMW = Culture Collection of the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

Species names in bold type are species transferred to Grosmannia in this study.

DNA sequence was obtained from GenBank.

Ex-type cultures.

Underlined species names are species transferred to Ceratocystiopsis in this study.

No anamorph-genus mentioned in the original description. We assign a genus here based on our interpretation of the original species description.

A large variety of potential outgroups were initially tested for suitability in the phylogenetic analysis used in this study. From these tests three species of Cryphonectria were selected as being the most appropriate and these include: Cry. cubensis (CBS 101281; LSU = AF408338; β-tubulin = DQ246580), Cry. havanensis (CBS 505.63; LSU = AF408339; β-tubulin = AY063478), and Cry. nitschkei (CBS 109776; LSU = AF408341; β-tubulin = DQ120768). The names used here are those published by Castlebury et al. (2002) in GenBank although we recognize that Gryzenhout et al. (2005) have shown that Cry. havanensis (CBS 505.63) is incorrectly identified and also represents Cry. cubensis.

DNA extraction and PCR

DNA was extracted from mycelium grown on 2 % MEA using the DNA extraction method described by Aghayeva et al. (2004). Two genes were amplified for sequencing and phylogenetic analysis. The 5' end of the nuclear large subunit rDNA was amplified using the primers LR0R (5' ACCCGCTGAACTTAAGC 3') and LR5 (5' TCCTGAGGGAAACTTCG 3') (http://www.biology.duke.edu/fungi/mycolab/primers.htm). Part of the β-tubulin gene was amplified with primers T10 (5' ACGATAGGTTCACCTCCAGAGAC 3') (O'Donnell & Cigelnik 1997) or Bt2a (5' GGTAACCAAATCGGTGC GCTTTC 3') in combination with Bt2b (5' GGTAACCAAATCGGTGCTGCTTTC 3') (Glass & Donaldson 1995). Reaction volumes for the PCR amplification were 50 μL and contained 5 μL 10 × PCR reaction buffer (Super-Therm, JMR Holdings, U.S.A.), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dNTP, 10 μM of each primer, 2 μL DNA and 2.5 U Super-Therm Taq polymerase (JMR Holdings, U.S.A.). The PCR conditions for the amplification of both the LSU and β-tubulin genes included denaturing for 3 min at 94 °C, annealing at 47–52 °C for 1 min, and elongation at 72 °C for 1 min. This was repeated for 35 cycles ending with a final elongation step at 72 °C for 5 min. Success of the PCR amplification was confirmed on a 1 % (w/v) agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. DNA was visualized under UV light. The PCR fragments were purified with QIAquick® PCR purification kit (Quiagen®) eluting the DNA in water.

DNA sequencing

Sequencing of the purified PCR fragments was performed using the primers noted above and the Big Dye™ Terminator v. 3.0 cycle sequencing premix kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.). The fragments were analyzed on an ABI PRISIM™ 377 or ABI PRISIM™ 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). DNA Sequence data were edited using Sequence Navigator (Applied Biosystems) and aligned in CLUSTAL-X (Thompson et al. 1997) and then in T-Coffee (Notredame et al. 2000) using multiple alignment algorithms. T-Coffee was used to combine the alignment results of Clustal X with the local and global pairwise alignments obtained in T-Coffee, to produce a multiple sequence alignment with the best agreement of these methods. The default parameters in T-Coffee were used for the analysis. Manual adjustments of the dataset were performed in PAUP v. 4.0b8 (Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony) (Swofford 2001) as follows: for the analysis of the partial LSU gene, sequences were trimmed at the 5' and 3' ends to align with DNA sequences from GenBank used for the outgroups. For the partial β-tubulin gene the sequences were trimmed on the 5' end to correspond with the beginning of exon 4 of the β-tubulin gene. Analyses were carried out using parsimony, neighbour-joining and maximum likelihood (Swofford 2001) and Bayesian inference (MrBayes 3.0b4) (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist 2001).

Phylogenetic analysis

Maximum parsimony: For parsimony analysis, ambiguous and missing nucleotides were eliminated and the remaining characters were weighted according to the consistency index (CI). A heuristic search was performed with tree-bisection-reconnection (TBR) branch swapping. The resulting trees were used to obtain a majority rule consensus tree. Confidence values were estimated using Bootstrap analysis (1000 replicates) with the full consensus option.

Bayesian inference: Data were analysed using a Bayesian approach based on a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis. A general time reversal (GTR+I+G) model as determined by AIC criteria of Modeltest (Posada & Crandall 1998) was used for the analysis. The proportion of sites was assumed to be invariable, while the rate of the remaining sites was drawn from a gamma distribution with six categories. All parameters were inferred from the data. Four Markov chains were initiated at random and the program was allowed to run for 2000000 generations with a sample frequency of 100. The analysis was repeated six times and consensus trees obtained from the six independent analyses were examined for consistency. One of the six analyses was used to calculate a consensus tree with mean branch lengths. The likelihood convergence was determined and these sampled trees were discarded as burn in. The following trees with their branch lengths were used to generate a consensus tree based on 50 % majority rule with mean branch lengths and posterior probabilities for the nodes using PAUP (Swofford 2001).

Neighbour-joining: A distance tree was calculated using Neighbour-joining analysis based on the evolutionary model that was determined as GTR+I+G based on AIC criteria using the Modeltest 3.06 (Posada & Crandall 1998). Distance settings were adjusted according to the Akaike information criteria (AIC) model: proportion invariable sites were assumed to be 0.4369 and the rates for variable sites were assumed to follow a gamma distribution with shape parameter of 0.5593. Confidence was determined by 1000 bootstrap replicates. The starting tree was obtained from the Neighbour-joining tree, the branch swap algorithm set to TBR (tree bisection reconnection).

Maximum likelihood: Likelihood settings were set according to GTR+I+G model as determined by AIC criteria in Modeltest 3.06 (Posada & Crandall 1998). Assumed proportion invariable sites were set to 0.4369. The variable sites were assumed to have a gamma distribution with a 0.5593 shape parameter. The search was performed heuristically with random stepwise addition and TBR branch swapping. Confidence values were estimated using bootstrap analysis (1000 replicates) determined by heuristic search and TBR branch swapping.

RESULTS

DNA sequence comparisons

The 5' region of the LSU gene resulted in amplicons in the range of 697–702 nucleotides. This amplicon included the D1 and D2 region of the LSU gene. Amplicons in the range of 218–334 nucleotides in length were obtained from the partial β-tubulin gene. This region included exon 4, exon 5 and the 5' end of exon 6, as well as intron 4 situated between exons 4 and 5, and intron 5 between exons 5 and 6. DNA sequences of the three exons were of equal length for all taxa studied. However introns 4 and 5 were highly variable in both nucleotide length and DNA sequence. Some taxa lacked either intron 4 or intron 5 or both introns. The high level of variability of the DNA sequence observed in the introns, and the presence or absence of the introns (Fig. 1), accounted for the large difference in β-tubulin sequence lengths.

Fig. 1.

Cladogram based on 50 % majority rule consensus tree (tree length = 383 steps; CI = 0.656; RI = 0.860) obtained from four trees produced by maximum parsimony analysis with the TBR algorithm, using a heuristic search on the combined data set of partial nuclear LSU and β-tubulin DNA sequence. Data was weighted according to consistency index. Bootstrap support values (1000 replicates) above 50 % are indicated at the branches. The tree was rooted to the outgroup consisting of three Cryphonectria spp. The following information is indicated in columns next to the taxa: β-tubulin introns (4 = intron 4 present; 5 = intron 5 present). Ascospore shapes are described, and the presence or absence of sheaths indicated. Anamorphs associated with each taxon (H = Hyalorhinocladiella; L = Leptographium; P = Pesotum, S = Sporothrix).

DNA sequence alignments resulted in 714 characters for the partial LSU gene and 402 characters for the partial β-tubulin gene. However, due to the high level of variability of the introns found in the β-tubulin region, the intron sequences were excluded from further analysis, resulting in 220 characters of the β-tubulin gene used in the analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis

Preliminary cladistic analysis based on parsimony showed that trees generated for both LSU (data not shown) and combined LSU/β-tubulin gene regions had similar topologies. Furthermore, the combined data set resulted in higher confidence values for the obtained groupings. Combined LSU and β-tubulin data sets (excluding β-tubulin introns), which consisted of a total of 934 characters, were thus used. Congruence of the LSU and β-tubulin datasets was not supported by the partition homogeneity test (PHT). This was most probably due to the highly conserved nature of the β-tubulin gene resulting in poor resolution of the terminal branches. The similar node topology of the trees obtained from the LSU and LSU/β-tubulin genes, and the increased bootstrap support for the groups obtained using the combined data set, justified that the data of these two genes should be considered together, irrespective of the incongruence of the loci.

Maximum parsimony: For the cladistic analysis of the combined data set, 39 missing and ambiguous characters were excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining 895 characters, 608 characters were constant, 48 variable characters were parsimony-uninformative and 239 characters were parsimony-informative. Characters were re-weighted according to the maximum consistency index. This resulted in 751 characters with a weight of 1, and 144 characters with a weight other than 1. Four trees with similar topologies were obtained using maximum parsimony analysis with the tree bisection reconnection (TBR) branch swapping algorithm. The deeper nodes were consistent in all four trees, with slight variations in the topology of the terminal nodes. From the four trees a 50 % majority rule consensus tree was compiled with the TBR algorithm. The tree length was 383 steps, CI = 0.656, and the retention index (RI) = 0.860. A consensus cladogram was obtained (Fig. 1).

The cladogram (Fig. 1) showed that the taxa are grouped in distinct, well-supported clades. Clade A (91 % bootstrap) included only taxa that have Leptographuim anamorph states. All the species in this group had intron 4 and lacked intron 5 in the β-tubulin gene (Fig. 1). Clade B (82 % bootstrap) consisted of several distinct groups. Within Clade B, Clade C (100 % bootstrap) formed a monophyletic group including the recently described species O. rollhansenianum J. Reid, Eyjólfsd. & Hausner and O. manitobense J. Reid & Hausner, as well as taxa previously residing in the genus Ceratocystiopsis. These taxa all have short perithecial necks and falcate ascospores, and are sensitive to cycloheximide. Two anamorph states are associated with taxa in this group. They are Sporothrix, the anamorph of O. ranaculosum (J.R. Bridges & T.J. Perry) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen, and Hyalorhinocladiella, associated with O. minuta-bicolor (R.W. Davidson) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen, O. minutum Siemaszko, O. minimum (Olchowecki & J. Reid) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen, O. rollhansenianum and O. manitobense.

Clade D (Fig. 1) had a relatively low bootstrap support of 66 %. The taxa in this clade were subdivided in numerous smaller clades with various levels of confidence support. Clade E (100 % bootstrap) included four taxa with Sporothrix anamorphs producing secondary conidia. Ophiostoma pluriannulatum (Hedgc.) Syd. & P. Syd., O. subannulatum Livingston & R.W. Davidson, and O. multiannulatum (Hedgc. & R.W. Davidson) Hendr. have naked (no sheath) reniform ascospores, and O. carpenteri J. Reid & Hausner has naked, narrowly clavate ascospores. Clade F had poor bootstrap support (60 %) and consists of two subclades (G and H). Within Clade G, O. ips, O. pulvinisporum X.D. Zhou & M.J. Wingf., and O. montium (Rumbold) Arx, formed one well-supported group (Clade J, 98 % bootstrap support). These species have pillow-shaped ascospores protected by a sheath and a continuum of anamorphs including Hyalorhinocladiella and Pesotum. The second subclade (I, with bootstrap 76 %) was less well defined and consisted of members of the O. piceae complex with Pesotum anamorphs and O. piliferum (Fr.) Syd. & P. Syd. Other species in this clade were O. ainoae H. Solheim and O. araucariae (Butin) de Hoog & R.J. Scheff. with Pesotum-like anamorphs, and O. distortum (Davidson) de Hoog & R.J. Scheff., O. flexuosum H. Solheim, and O. piliferum with Sporothrix anamorphs. All species in this clade had intron 4 and lacked intron 5 in the β-tubulin gene (Fig. 1).

Clade H (76 % bootstrap) consisted only of taxa with Sporothrix anamorphs and ascospores varying from orange section to allantoid in shape. The species in this clade all lacked intron 4 and had intron 5 in the β-tubulin gene (Fig. 1). In this clade, O. nigrocarpum (R.W. Davidson) de Hoog grouped separately from the other taxa that formed a clade with 98 % bootstrap support. Species in this clade include Sporothrix schenckii Hektoen & C.F. Perkins, the type species for the anamorph-genus Sporothrix, O. stenoceras (Robak) Nannf., S. inflata de Hoog, O. fusiforme D.N. Aghayeva & M.J. Wingf. and O. lunatum D.N. Aghayeva & M.J. Wingf. The three species of Ophiostoma found within infructescences of Protea spp. in South Africa, O. splendens G.J. Marias & M.J. Wingf., O. protearum G.J. Marias & M.J. Wingf., and O. africanum G.J. Marias & M.J. Wingf., constituted a well-defined, smaller clade with strong bootstrap support within Clade H.

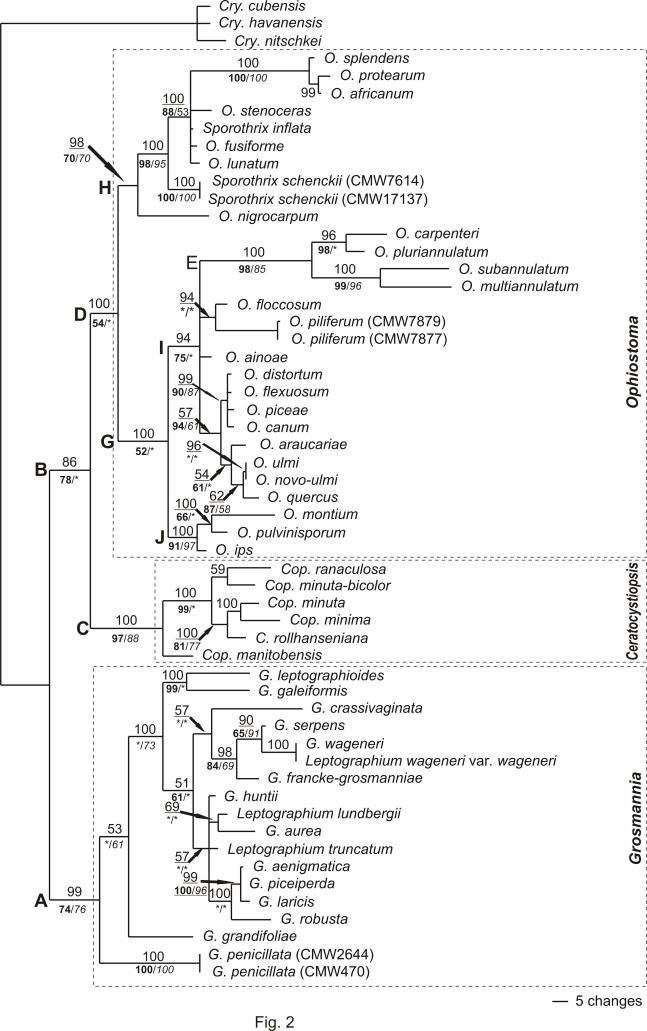

Bayesian inference: Consistent results were obtained in the six runs of the Bayesian phylogenetic analysis (Model GTR+I+G). The topologies of the obtained trees differed only slightly in the terminal nodes where low confidence values were obtained. No variations were observed in the deeper nodes supported by high confidence values. The stationary phase of the Markov chains was observed after 33000 generations. The first 2000 trees (representing 200000 generations) were thus discarded and 18000 trees were included to calculate the 50 % rule consensus tree for each run. One of the phylogenetic trees obtained is presented in Fig. 2. The calculated confidence values (posterior probabilities) are indicated above the relevant nodes where support exceeded 50 %.

Fig. 2.

Phylogram resulting from a Bayesian Monte Carlo Markov chain (MCMC) analyses of 934 nucleotides of partial LSU and β-tubulin sequences. The 50 % Majority rule consensus tree was obtained from 18000 trees. The numbers above each node indicate posterior probabilities obtained from Bayesian analyses. Bootstrap values (1000 replicates) obtained for Neighbour-joining and Maximum likelihood analyses are indicated below each node in bold and italic, respectively. A support less than 50 % is represented by *. In Neighbour-joining analysis group E is situated basal to groups I and J, and not part of group I. In Maximum likelihood analysis groups D and G are not supported, and group E forms a separate clade not linked to any other clade.

The deeper nodes obtained from the Bayesian analysis (MB) were identical to those obtained with maximum parsimony (MP). Support for the groups was, however, higher for Bayesian inference in the deeper branches than the Bootstrap support obtained for MP: group A (MB = 99 %; MP = 91 %), group B (MB = 86 %; MP = 82 %), group C (MB = 100 %; MP = 100 %), group D (MB = 100 %; MP = 66 %). Group D consisted of several subgroups. Groups E (MB = 100 %; MP = 100 %), H (MB = 98 %; MP = 76 %), and J (MB = 100 %; MP = 98 %) remain clustered together with high statistical support. However, the topology of the groups found within group D, obtained from Bayesian inference, differ in structure from the topology obtained in MP analysis. One major difference in topology is that group E forms as a separate group basal to group H and G in the MP analysis, while Bayesian inference resulted in group E forming part of group G. However, group E remained a separate entity with high posterior probability support.

Neighbour-joining: Phylogenetic distance was determined by Neighbour-joining (NJ) analyses based on the general time reversal model. Statistical support for the nodes was calculated using 1000 NJ bootstrap repeats. NJ support values for nodes obtained are indicated bold (Fig. 2). The topology obtained from NJ is similar to that obtained from Bayesian inference. With the exception of group E, clustering basal to group J and I closest to group G and not basal to groupings G and H or within group F as observed on MP and Bayesian analysis respectively.

Maximum likelihood: For the phylogenetic relationship estimated using maximum likelihood (ML), the GTR+I+G evolutionary model determined by Model Test based on Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) was applied. Estimated proportion invariable sites (I) was set to 0.4369 and the shape parameter for gamma distribution (G) was set to 0.5595 and no molecular clock was enforced on the data set. Bootstrap values for the groupings were determined by 1000 bootstrap repeats. ML support (50 % or higher) for groups obtained are indicated in italics (Fig. 2) on the phylogenetic tree obtained by Bayesian inference. Groups A–C, E, and H–J were supported by ML. However the deeper node resolution of these groups differs significantly from MP and Bayesian inference. Groupings D and G were not supported and group B had poor ML statistical support.

For consistency in the discussion we refer to the clades obtained in parsimony analysis, and the groups obtained in Bayesian, NJ and ML analysis, as groups.

TAXONOMY

Analyses of phylogenetic data obtained in this study provided strong support for the hypothesis that the genus Ophiostoma includes at least three monophyletic lineages. Two of these lineages correspond clearly with a combination of both anamorph and teleomorph characters. These characters have also previously been recognised as taxonomically informative and have been employed to define the two genera, Grosmannia and Ceratocystiopsis. Based on robust phylogenetic support as well as clearly defined morphological characters, we re-instate these genera with emended descriptions and establish the necessary new combinations. The description of the genus Ophiostoma is emended to reflect these taxonomic changes.

Ophiostoma Syd. & P. Syd., Ann. Mycol. 17: 43. 1919. emend. Z.W. de Beer, Zipfel & M.J. Wingf.

= Linostoma Höhn., Ann. Mycol. 16: 91. 1918. (non Wallich, Cat. East Indies Comp., London. 1828).

= Ophiostoma Syd. & P. Syd. section Brevirostrata Nannf., Svenska SkogsvFör. Tidskr. 32: 407. 1934.

= Ophiostoma Syd. & P. Syd. section Longirostrata Nannf. pro parte, Svenska SkogsvFör. Tidskr. 32: 407. 1934.

Ascocarps subhyaline to dark brown to black, bases globose; necks straight or flexuous, cylindrical, brown to black; ostiole often surrounded by ostiolar hyphae. Asci 8-spored, evanescent, globose to broadly clavate. Ascospores hyaline, aseptate, cylindrical, lunate, allantoid, reniform, orange section- or pillow-shaped, sometimes with a hyaline, gelatinous sheath. Anamorphs most commonly Sporothrix and/or Pesotum, occasionaly Hyalorhinocladiella-like, rarely Leptographium-like. Phylogenetically classified in the Ophiostomatales.

Type species: Ophiostoma piliferum Fr.: Fr. Syd. & P. Syd., Ann. Mycol. 17: 43. 1919.

Basionym: Sphaeria pilifera Fr., Syst Mycol. 2: 472. 1822.

≡ Ceratostoma piliferum (Fr.) Fuckel, Symb. Mycol. p. 128. 1869.

≡ Ceratostomella pilifera (Fr.) G. Winter, Rabenh. Kryptogamen-Flora 1: 252. 1887.

≡ Linostoma piliferum (Fr.) Höhn., Ann. Mycol. 16: 91. 1918.

≡ Ceratocystis pilifera (Fr.) C. Moreau, Rev. Mycol. (Paris), Suppl. Colon. 17: 22. 1952.

Anamorph: Sporothrix (De Hoog 1974).

Ceratocystiopsis H.P. Upadhyay & W.B. Kendr., Mycologia 67: 799. 1975. emend. Z.W. de Beer, Zipfel & M.J. Wingf.

Ascocarps subhyaline to dark brown to black, bases globose to subglobose; necks relatively short, mostly tapered toward the apex, sometimes surrounded by a collar-like structure; ostiolar hyphae convergent or lacking. Asci 8-spored, evanescent, fusiform, clavate or ellipsoidal, hyaline. Ascospores hyaline, aseptate, elongate, falcate, or slender with obtuse ends, sometimes with bulbous swelling, most often with a hyaline sheath. Sensitive to cycloheximide. Anamorphs Hyalorhinocladiella or Sporothrix-like. Phylogenetically classified in the Ophiostomatales within a monopyletic lineage including Ceratocystiopsis minuta.

-

Type species: Ceratocystiopsis minuta (Siemaszko) H.P. Upadhyay & W.B. Kendr., Mycologia 67: 800. 1975.

Basionym: Ophiostoma minutum Siemaszko, Planta Pol. 7: 23. 1939.

- ≡ Ceratostomella minuta (Siemaszko) R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 34: 655. 1942.

- ≡ Ceratocystis minuta (Siemaszko) J. Hunt, Lloydia 19: 49. 1956.

- = Ceratocystis dolominuta H.D. Griffin, Canad. J. Bot. 46: 702. 1968.

Anamorph: Hyalorhinocladiella (Upadhyay 1981).

Note: Synonymy of C. dolominuta and Cop. minuta suggested by Upadhyay (1981).

-

Ceratocystiopsis brevicomi Hsiau & T.C. Harr., Mycologia 89: 661. 1997.

Anamorph: not assigned to a genus (Hsiau & Harrington 1997).

Phylogenetic information: Ceratocystiopsis brevicomi is distinct from, but close to Cop. ranaculosa and Cop. collifera (Hsiau & Harrington 1997, Six & Paine 1999).

-

Ceratocystiopsis collifera Marm. & Butin, Sydowia 42: 197. 1990.

Basionym: Ophiostoma colliferum (Marm. & Butin) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen, Mycol. Res. 97: 631. 1993.

Anamorph: Sporothrix (Marmolejo & Butin 1990).

Phylogenetic information: Ceratocystiopsis collifera is closely related to Cop. minima and Cop. parva (Hausner et al. 1993a).

-

Ceratocystiopsis concentrica (Olchow. & J. Reid) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 121. 1981.

Basionym: Ceratocystis concentrica Olchow. & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 52: 1679. 1974.

- ≡ Ophiostoma concentricum (Olchow. & J. Reid) Hausner & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 81: 874. 2003.

Anamorph: Hyalorhinocladiella (De Hoog 1993).

Phylogenetic information: Ceratocystiopsis concentrica is part of the Minuta complex sensu Hausner & Reid (2003).

-

Ceratocystiopsis manitobensis (J. Reid & Hausner) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500805.

Basionym: Ophiostoma manitobense J. Reid & Hausner, Canad. J. Bot. 81: 46. 2003.

Anamorph: Not assigned to a genus (Hausner et al. 2003), but morphologically similar to Hyalorhinocladiella.

-

Ceratocystiopsis minima (Olchow. & J. Reid) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 129. 1981.

Basionym: Ceratocystis minima Olchow. & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 52: 1684. 1974.

- ≡ Ophiostoma minimum (Olchow. & J. Reid) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen, Mycol. Res. 97: 631. 1993.

Anamorph: Hyalorhinocladiella (Upadhyay 1981).

-

Ceratocystiopsis minuta-bicolor (R.W. Davidson) H.P. Upadhyay & W.B. Kendr., Mycologia 67: 800. 1975.

Basionym: Ceratocystis minuta-bicolor R.W. Davidson, Mycopath. Mycologia Appl. 28: 280. 1966.

- ≡ Ophiostoma minutum-bicolor (R.W. Davidson) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen, Mycol. Res. 97: 631. 1993.

- = Ceratocystis pallida H.D. Griffin, Canad. J. Bot. 46: 708. 1968.

Anamorph: Hyalorhinocladiella minuta-bicolor H.P. Upadhyay & W.B. Kendr., Mycologia 67: 800. 1975.

Note: Synonymy of C. pallida with Cop. minuta-bicolor suggested by Upadhyay (1981).

-

Ceratocystiopsis pallidobrunnea (Olchow. & J. Reid) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 133. 1981.

Basionym: Ceratocystis pallidobrunnea Olchow. & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 52: 1685. 1974.

- ≡ Ophiostoma pallidobrunneum (Olchow. & J. Reid) Hausner & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 81: 875. 2003.

Anamorph: Hyalorhinocladiella (De Hoog 1993).

Phylogenetic information: Part of the Minuta complex sensu Hausner & Reid (2003).

-

Ceratocystiopsis parva (Olchow. & J. Reid) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500806.

Basionym: Ceratocystis parva Olchow. & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 52. 1686. 1974.

- ≡ Ophiostoma parvum (Olchow. & J. Reid) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen, Mycol. Res. 97: 631. 1993.

Anamorph: not assigned to an anamorph-genus (Olchowecki & Reid 1973), but similar to Hyalorhinocladiella.

Phylogenetic information: Upadhyay treated this species as synonym of Cop. minima, but Hausner, Reid & Klassen (1993a) showed that Cop. parva is closely related to, but distinct from Cop. minima and Cop. minuta.

-

Ceratocystiopsis ranaculosa J.R. Bridges & T.J. Perry, Mycologia 79: 631. 1987.

- ≡ Ophiostoma ranaculosum (J.R. Bridges & T.J. Perry) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen, Mycol. Res. 97: 631. 1993.

Anamorph: Sporothrix (Bridges & Perry 1987).

-

Ceratocystiopsis rollhanseniana (J. Reid, Eyjólfsd. & Hausner) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500807.

Basionym: Ophiostoma rollhansenianum J. Reid, Eyjólfsd. & Hausner, Canad. J. Bot. 81: 44. 2003.

Anamorph: not assigned to a genus (Hausner et al. 2003), but morphologically similar to Hyalorhinocladiella.

Status of other species linked to Ceratocystiopsis

-

Ceratocystiopsis alba (DeVay, R.W. Davidson & W.J. Moller) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 120. 1981.

Basionym: Ceratocystis alba DeVay, R.W. Davidson & W.J. Moller, Mycologia 60: 636. 1968.

Anamorph: Hyalorhinocladiella (Upadhyay 1981).

Phylogenetic information: Ceratocystiopsis alba is phylogenetically unrelated to any of the genera in the Ophiostomatales (Hausner et al. 1993a).

-

Ophiostoma carpenteri J. Reid & Hausner, Canad. J. Bot. 81: 42. 2003.

Anamorph: not assigned to a genus (Hausner et al. 2003), but morphologically similar to Hyalorhinocladiella.

Phylogenetic information: Outside the Minuta complex, appears to be related to O. retusum (Hausner et al. 1993a, Hausner & Reid 2003).

-

Ceratocystiopsis conicicollis (Olchow. & J. Reid) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 122. 1981.

Basionym: Ceratocystis conicicollis Olchow. & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 52: 1680. 1974.

Anamorph: Hyalorhinocladiella (Upadhyay 1981).

Phylogenetic information: none – status uncertain.

Grosmannia crassivaginata (H.D. Griffin) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf. (see under Grosmannia, this study).

-

Ophiostoma crenulatum (Olchow. & J. Reid) Hausner & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 81: 875. 2003.

Basionym: Ceratocystis crenulata Olchow. & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 52: 1681. 1974.

- ≡ Ceratocystiopsis crenulata (Olchow. & J. Reid) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 124. 1981.

Anamorph: Hyalorhinocladiella (Upadhyay 1981).

Phylogenetic information: Outside the Minuta complex, appears to be related to O. fasciatum (Hausner & Reid 2003).

-

Cornuvesica falcata (E.F. Wright & Cain) C.D. Viljoen, M.J. Wingf. & K. Jacobs, Mycol. Res. 104: 366.

Basionym: Ceratocystis falcata E.F. Wright & Cain, Canad. J. Bot. 39: 1226. 1961.

- ≡ Ceratocystiopsis falcata (E.F. Wright & Cain) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 125. 1981.

Anamorph: Chalara-like (Viljoen et al. 2000).

Phylogenetic information: Cornuvesica falcata is phylogenetically unrelated to the Ophiostomatales (Hausner et al. 2000).

-

Ophiostoma fasciatum (Olchow. & J. Reid) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen, Mycol. Res. 97: 631. 1993.

Basionym: Ceratocystis fasciata Olchow. & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 52: 1682. 1974.

- = Ceratocystis spinifera Olchow. & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 52: 1686. 1974.

Anamorph: Hyalorhinocladiella (Upadhyay 1981).

Phylogenetic information: Ophiostoma fasciatum is not part of the Minuta complex, and related to O. crenulatum and O. ips (Hausner et al. 1993a, Hausner & Reid 2003).

-

Ophiostoma longisporum (Olchow. & J. Reid) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen, Mycol. Res. 97: 631. 1993.

Basionym: Ceratocystis longispora Olchow. & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 52: 1683. 1974.

- ≡ Ceratocystiopsis longispora (Olchow. & J. Reid) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 128. 1981.

Anamorph: Sporothrix (Upadhyay 1981).

Phylogenetic information: Ophiostoma longisporum is not part of the Minuta complex, and falls basal to O. ips within Ophiostoma (Hausner et al. 1993a, Hausner & Reid 2003).

-

Ceratocystiopsis ochracea (H.D. Griffin) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 132. 1981.

Basionym: Ceratocystis ochracea H.D. Griffin, Canad. J. Bot. 46: 706. 1968.

Anamorph: no anamorph on type material and no description of anamorph in Griffin (1968).

Phylogenetic information: none – status uncertain.

-

Gondwanamyces proteae (M.J. Wingf., P.S. van Wyk & Marasas) G.J. Marais & M.J. Wingf., Mycologia 90: 139. 1998.

Basionym: Ceratocystiopsis proteae M.J. Wingf., P.S. van Wyk & Marasas, Mycologia 80: 24. 1988.

Anamorph: Knoxdaviesia proteae M.J. Wingf., P.S. van Wyk & Marasas, Mycologia 80: 26. 1988.

Phylogenetic information: Gondwanamyces proteae has been placed in the order Microascales, and is unrelated to the Ophiostomatales (Viljoen et al. 1999).

-

Ophiostoma retusum (R.W. Davidson & T.E. Hinds) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen, Mycol. Res. 97: 631. 1993.

Basionym: Ceratocystis retusi R.W. Davidson & T. E. Hinds, Mycologia 64: 407. 1972.

- ≡ Ceratocystiopsis retusi (R.W. Davidson & T.E. Hinds) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 135. 1981.

Anamorph: Sporothrix (Seifert et al. 1993, Benade et al. 1998).

Phylogenetic information: Ophiostoma retusum is not part of the Minuta complex, but closer to O. ips and O. carpenteri (Hausner et al. 1993a, Hausner & Reid 2003).

-

Ceratocystiopsis spinulosa (H.D. Griffin) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 136. 1981.

Basionym: Ceratocystis spinulosa H.D. Griffin, Canad. J. Bot 46: 713. 1968.

Anamorph: Hyalorhinocladiella (De Hoog 1993).

Phylogenetic information: none – status uncertain.

Grosmannia Goid., Boll. Staz. Patol. Veg. 16: 27. 1936. emend. Z.W. de Beer, Zipfel & M.J. Wingf.

= Europhium A.K. Parker, Canad. J. Bot. 35: 175. 1957.

Ascomata black, bases globose, seldom ornamented; necks absent or present, pigmented, tapered toward apex; ostiolar hyphae mostly absent, when present, convergent or divergent. Asci 8-spored, evanescent. Ascospores hyaline, aseptate, reniform, curved, allantoid, fusiform, orange section- or hat-shaped, often invested in a sheath. Anamorph Leptographium, or with synnemata appearing as a loose aggregation of Leptographium conidiophores. Phylogenetically classified in the Ophiostomatales within a monophyletic group containing Grosmannia penicillata. β-tubulin gene contains intron 4 and lacks intron 5.

-

Type species: Grosmannia penicillata (Grosmann) Goid., Boll. Staz. Patol. Veg. 16: 27. 1936.

Basionym: Ceratostomella penicillata Grosmann, Hedwigia 72: 190. 1932.

- ≡ Ophiostoma penicillatum (Grosmann) Siemaszko, Planta Pol. 7: 24. 1939.

- ≡ Ceratocystis penicillata (Grosmann) C. Moreau, Rev. Mycol. (Paris), Suppl. Colon. 17: 22. 1952.

Anamorph: Leptographium penicillatum Grosmann, Z. Parasitenk. 3: 94. 1931.

- ≡ Scopularia penicillata (Grosmann) Goid., Boll. Staz. Patol. Veg. 16: 39. 1936.

- ≡ Verticicladiella penicillata (Grosmann) W.B. Kendr., Canad. J. Bot. 40: 776. 1962.

-

Grosmannia abiocarpa (R.W. Davidson) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500808.

Basionym: Ceratocystis abiocarpa R.W. Davidson, Mycopathol. Mycol. Appl. 28: 273. 1966.

- ≡ Ophiostoma abiocarpum (R.W. Davidson) T.C. Harr., Mycotaxon 28: 41. 1987.

Anamorph: Leptographium (Upadhyay 1981).

Phylogenetic information: Grosmannia abiocarpa is closely related to G. penicillata and G. huntii (Jacobs et al. 2001).

-

Grosmannia aenigmatica (K. Jacobs, M.J. Wingf. & Yamaoka) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500809.

Basionym: Ophiostoma aenigmaticum K. Jacobs, M.J. Wingf. & Yamaoka, Mycol. Res. 102: 291. 1998.

Anamorph: Leptographium aenigmaticum M.J. Wingf. & Yamaoka, Mycol. Res. 102: 291. 1998.

-

Grosmannia americana (K. Jacobs & M.J. Wingf.) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500810.

Basionym: Ophiostoma americanum K. Jacobs & M.J. Wingf., Canad. J. Bot. 75: 1318. 1997.

Anamorph: Leptographium americanum K. Jacobs & M.J. Wingf., Canad. J. Bot. 75: 1318. 1997.

Phylogenetic information: Grosmannia americana is closely related to G. penicillata (Jacobs et al. 2001) and G. huntii (Jacobs et al. 2001, Kim et al. 2004).

-

Grosmannia aurea (R.C. Rob.-Jeffr. & R.W. Davidson) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500811.

Basionym: Europhium aureum R.C. Rob. & R.W. Davidson, Canad. J. Bot. 46: 1525. 1968.

- ≡ Ceratocystis aurea (R.C. Rob.-Jeffr. & R.W. Davidson) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 37. 1981.

- ≡ Ophiostoma aureum (R.C. Rob.-Jeffr. & R.W. Davidson) T.C. Harr., Mycotaxon 28: 41. 1987.

Anamorph: Leptographium aureum M.J. Wingf., Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 85: 92. 1985.

-

Grosmannia cainii (Olchow. & J. Reid) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500812.

Basionym: Ceratocystis cainii Olchow. & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 52: 1697. 1974.

- ≡ Ophiostoma cainii (Olchow. & J. Reid) T.C. Harr., Mycotaxon 28: 41. 1987.

Anamorph: Pesotum (Okada et al. 1998, Kim et al. 2005).

Phylogenetic information: Grosmannia cainii is closely related to G. leptographioides (Kim et al. 2005).

-

Grosmannia clavigera (R.C. Rob.-Jeffr. & R.W. Davidson) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500813.

Basionym: Europhium clavigerum R.C. Rob.-Jeffr. & R.W. Davidson, Canad. J. Bot. 46: 1523. 1968.

- ≡ Ceratocystis clavigera (R.C. Rob.-Jeffr. & R.W. Davidson) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 40. 1981.

- ≡ Ophiostoma clavigerum (R.C. Rob.-Jeffr. & R.W. Davidson) T.C. Harr., Mycotaxon 28: 41. 1987.

Anamorph: Leptographium clavigerum (H.P. Upadhyay) T.C. Harr., Six & McNew, Mycologia 95: 791. 2003.

- ≡ Graphiocladiella clavigera H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 40. 1981.

- ≡ Pesotum clavigerum (H.P. Upadhyay) G. Okada & Seifert, Canad. J. Bot. 76: 1503. 1998.

Phylogenetic information: Grosmannia clavigera is closely related to G. robusta and G. aurea (Kim et al. 2004, Lim et al. 2004, Kim et al. 2005).

-

Grosmannia crassivaginata (H.D. Griffin) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500814.

Basionym: Ceratocystis crassivaginata H.D. Griffin, Canad. J. Bot. 46: 701. 1968.

- ≡ Ceratocystiopsis crassivaginata (H.D. Griffin) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 123. 1981.

- ≡ Ophiostoma crassivaginatum (H.D. Griffin) T.C. Harr., Mycotaxon 28: 41. 1987.

Anamorph: Leptographium crassivaginatum M.J. Wingf., Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 85: 92. 1985.

-

Grosmannia cucullata (H. Solheim) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500815.

Basionym: Ophiostoma cucullatum H. Solheim, Nordic J. Bot. 6: 202–203. 1986.

Anamorph: Pesotum (Okada et al. 1998).

Phylogenetic information: Grosmannia cucullata groups with several other Leptographium spp. (Hausner et al. 2000).

-

Grosmannia davidsonii (Olchow. & J. Reid) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500816.

Basionym: Ceratocystis davidsonii Olchow. & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 52: 1698. 1974.

- ≡ Ophiostoma davidsonii (Olchow. & J. Reid) H. Solheim, Nordic J. Bot. 6: 203. 1986.

Anamorph: Pesotum (Okada et al. 1998).

Phylogenetic information: Grosmannia davidsonii groups within the Leptographium clade (Hausner et al. 2000).

-

Grosmannia dryocoetidis (W.B. Kendr. & Molnar) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov.

MycoBank MB500817.

Basionym: Ceratocystis dryocoetidis W.B. Kendr. & Molnar, Canad. J. Bot. 43: 39. 1965.

- ≡ Ophiostoma dryocoetidis (W.B. Kendr. & Molnar) de Hoog & R.J. Scheff., Mycologia 76: 297. 1984.

Anamorph: Leptographium dryocoetidis M.J. Wingf., Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 85: 92. 1985.

- ≡ Verticicladiella dryocoetidis W.B. Kendr. & Molnar, Canad. J. Bot. 43: 39. 1965.

Phylogenetic information: Grosmannia dryocoetidis is related to G. huntii, G. francke-grosmanniae and G. penicillata among other species with Leptographium anamorphs (Jacobs et al. 2001, Kim et al. 2005).

-

Grosmannia europhioides (E.F. Wright & Cain) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500818.

Basionym: Ceratocystis europhioides E.F. Wright & Cain, Canad. J. Bot. 39: 1222. 1961.

- ≡ Ophiostoma europhioides (E.F. Wright & Cain) H. Solheim, Nordic J. Bot. 6: 203. 1986.

Anamorph: Leptographium (Solheim 1986).

Phylogenetic information: Upadhyay (1981) treated G. europhioides as synonym of G. piceiperda, but Solheim (1986), Harrington (1988), Yamaoka (1997) and Jacobs et al. (1998) treated the two species as distinct. However, Harrington (1988) considered G. pseudoeurophioides a synonym of G. europhioides. Jacobs & Wingfield (2001) treated these species as synonyms of G. piceiperda. Phylogenetic data of Hausner et al. (1993b, 2000) suggest that these represent three distinct species.

-

Grosmannia francke-grosmanniae (R.W. Davidson) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500819.

Basionym: Ceratocystis francke-grosmanniae R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 63: 6. 1971.

- ≡ Ophiostoma francke-grosmanniae (R.W. Davidson) de Hoog & R.J. Scheff., Mycologia 76: 297. 1984.

Anamorph: Leptographium francke-grosmanniae K. Jacobs & M.J. Wingf., In Jacobs & Wingfield, Leptographium species: 99. 2001.

-

Grosmannia galeiformis (B.K. Bakshi) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500820.

Basionym: Ceratocystis galeiformis Bakshi, Mycol. Pap. 35: 13. 1951.

- ≡ Ophiostoma galeiforme (B.K. Bakshi) Math.-Käärik, Medd. Skogsforskninginst. 43: 47. 1953.

Anamorph: Leptographium (Harrington et al. 2001, Zhou et al. 2004b).

Note: The anamorph of G. galeiformis exhibits predominantly synnematous structures in culture (Zhou et al. 2004b). However, these might be viewed as a loose aggregation of mononematous conidiophores, and the anamorph of G. galeiformis was attributed to Leptographium based on phylogenetic association by Zhou et al. (2004b).

-

Grosmannia grandifoliae (R.W. Davidson) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500821.

Basionym: Ceratocystis grandifoliae R.W. Davidson, Mem. N.Y. Bot. Gard. 28: 45. 1976.

- ≡ Ophiostoma grandifoliae (R.W. Davidson) T.C. Harr., Mycotaxon 28: 41. 1987.

Anamorph: Leptographium grandifoliae M.J. Wingf., Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 85: 92. 1985.

-

Grosmannia huntii (R.C. Rob.-Jeffr.) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500822.

Basionym: Ceratocystis huntii R.C. Rob.-Jeffr., Canad. J. Bot. 42: 528. 1964.

- ≡ Ophiostoma huntii (R.C. Rob.-Jeffr.) de Hoog & R.J. Scheff., Mycologia 76: 297. 1984.

Anamorph: Leptographium huntii M.J. Wingf., Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 85: 92. 1985.

-

Grosmannia laricis (K. van der Westh., Yamaoka & M.J. Wingf.) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500823.

Basionym: Ophiostoma laricis K. van der Westh., Yamaoka & M.J. Wingf., Mycol. Res. 99: 1336. 1995.

Anamorph: Leptographium laricis K. van der Westh., Yamaoka & M.J. Wingf., Mycol. Res. 99: 1336. 1995.

-

Grosmannia leptographioides(R.W. Davidson) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500824.

Basionym: Ceratostomella leptographioides R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 34: 657. 1942.

- ≡ Ophiostoma leptographioides (R.W. Davidson) Arx, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 18: 211. 1952.

- ≡ Ceratocystis leptographioides (R.W. Davidson) J. Hunt, Lloydia 19: 28. 1956.

Anamorph: Leptographium leptographioides K. Jacobs & M.J. Wingf., In Jacobs & Wingfield, Leptographium species: 118. 2001.

-

Grosmannia olivacea (Mathiesen) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500825.

Basionym: Ophiostoma olivaceum Mathiesen, Svensk. Bot. Tidskr. 45: 212. 1951.

- ≡ Ceratocystis olivacea (Mathiesen) J. Hunt, Lloydia 19: 29. 1956.

Anamorph: Pesotum (Okada et al. 1998).

Phylogenetic information: Grosmannia olivacea groups within the Leptographium group (Kim et al. 2005).

-

Grosmannia piceiperda (Rumbold) Goid., Boll. Staz. Patol. Veg. 16: 255. 1936.

Basionym: Ceratostomella piceiperda Rumbold, J. Agric. Res. 52: 436. 1936. [as `piceaperda']

- ≡ Ophiostoma piceiperdum (Rumbold) Arx, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 18: 211. 1952.

- ≡ Ceratocystis piceiperdum (Rumbold) C. Moreau, Rev. Mycol. (Paris), Suppl. Colon. 17: 22. 1952.

Anamorph: Leptographium piceiperdum K. Jacobs, M.J. Wingf. & Crous, Mycol. Res. 104: 240. 2000. [as `piceaperdum']

-

Grosmannia pseudoeurophioides (Olchow. & J. Reid) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500826.

Basionym: Ceratocystis pseudoeurophioides Olchow. & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 52: 1700. 1974.

- ≡ Ophiostoma pseudoeurophioides (Olchow. & J. Reid) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen, Canad. J. Bot. 71: 1264. 1993.

Anamorph: Leptographium (Hausner et al. 1993b). Phylogenetic information: This species was considered a synonym of G. penicillata (Upadhyay 1981), of G. europhioides (Harrington 1988) and of G. piceiperda (Jacobs et al. 1998, Jacobs & Wingfield 2001). However, phylogenetic data of Hausner et al. (1993b, 2000), showed that G. pseudoeurophioides is distinct from all three of the above-mentioned species.

-

Grosmannia radiaticola (J.-J. Kim, Seifert, & G.-H. Kim) Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500827.

Basionym: Ophiostoma radiaticola J.-J. Kim, Seifert, & G.-H. Kim, Mycotaxon 91: 486. 2005.

Anamorph: Pesotum pini (L.J. Hutchison & J. Reid) G. Okada & Seifert, Canad. J. Bot. 76: 1504. 1998.

- ≡ Hyalopesotum pini L.J. Hutchison & J. Reid, N.Z. J. Bot. 26: 90. 1988.

Phylogenetic information: This fungus is closely related to G. galeiformis (Kim et al. 2005).

-

Grosmannia robusta (R.C. Rob.-Jeffr. & R.W. Davidson) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500828.

Basionym: Europhium robustum R.C. Rob.-Jeffr. & R.W. Davidson, Canad. J. Bot. 46: 1525. 1968.

- ≡ Ceratocystis robusta (R.C. Rob.-Jeffr. & R.W. Davidson) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 58. 1981.

- ≡ Ophiostoma robustum (R.C. Rob.-Jeffr. & R.W. Davidson) T.C. Harr., Mycotaxon 28: 42. 1987.

Anamorph: Leptographium robustum M.J. Wingf., Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 85: 92. 1985.

-

Grosmannia sagmatospora (E.F. Wright & Cain) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500829.

Basionym: Ceratocystis sagmatospora E.F. Wright & Cain, Canad. J. Bot. 39: 1226. 1961.

- ≡ Ophiostoma sagmatosporum (E.F. Wright & Cain) H. Solheim, Nordic J. Bot. 6: 203. 1986.

Anamorph: Pesotum sagmatosporum (H.P. Upadhyay & W.B. Kendr.) G. Okada & Seifert, Canad. J. Bot. 76: 1504.

- ≡ Phialographium sagmatosporae H.P. Upadhyay & W.B. Kendr., Mycologia 66: 183. 1974.

- ≡ Graphium sagmatosporae (H.P. Upadhyay & W.B. Kendr.) M.J. Wingf. & W.B. Kendr., Mycol. Res. 95: 1332. 1991.

Phylogenetic information: Grosmannia sagmatospora falls within the Leptographium group (Kim et al. 2005).

-

Grosmannia serpens Goid., Goidánich, Boll. Staz. Patol. Veg. 16: 27. 1936.

- ≡ Ophiostoma serpens (Goid.) Arx, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 18: 211. 1952.

- ≡ Ceratocystis serpens (Goid.) C. Moreau, Rev. Mycol. (Paris), Suppl. Colon. 17: 22. 1952.

Anamorph: Leptographium serpens (Goid.) M.J. Wingf., Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 85: 92. 1985.

- ≡ Scopularia serpens Goid., Boll. Staz. Patol. Veg. 16: 42. 1936.

- ≡ Verticicladiella serpens (Goid.) W.B. Kendr., Canad. J. Bot. 40: 781. 1962.

-

= Verticicladiella alacris M.J. Wingf. & Marasas, Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 75: 22. 1980.

- ≡ Leptographium alacre (M.J. Wingf. & Marasas) M. Morelet, Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Archéol. Toulon Var 40: 44. 1988.

- = Leptographium gallaeciae F. Magan (nom. inval.).

-

Grosmannia vesca (R.W. Davidson) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500830.

Basionym: Ceratocystis vesca R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 50: 666. 1958.

- ≡ Ophiostoma vescum (R.W. Davidson) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen. Can J. Bot. 71: 1264. 1993.

Anamorph: Pesotum (Okada et al. 1998).

Phylogenetic information: Grosmannia vesca was treated as a synonym of G. olivacea (Griffin 1968, Olchowecki & Reid 1973, Upadhyay 1981). However, G. vesca groups close to but distinct from G. olivacea, G. crassivaginata, G. francke-grosmanniae and G. cucullata (Hausner et al. 1993b, 2000).

-

Grosmannia wageneri (Goheen & F.W. Cobb) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB500831.

Basionym: Ceratocystis wageneri Goheen & F.W. Cobb, Phytopathology 68: 1193. 1978.

- ≡ Ophiostoma wageneri (Goheen & F.W. Cobb) T.C. Harr., Mycotaxon 28: 42. 1987.

Anamorph: Leptographium wageneri var. ponderosae (T.C. Harr. & F.W. Cobb) T.C. Harr. & F.W. Cobb, Mycotaxon 30: 505. 1987.

- ≡ Verticicladiella wageneri var. ponderosae T.C. Harr. & F.W. Cobb, Mycol. 78: 568. 1986.

Note: Teleomorph structures for G. wageneri have been observed only once and these were associated with Leptographium wageneri var. ponderosae (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001), of which an isolate was included in the present study. Teleomorphs have never been observed for L. wageneri var. wageneri (also included in this study) and L. wageneri var. pseudotsugae (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001).

Status of other species linked to Leptographium

-

Ophiostoma brevicolle (R.W. Davidson) de Hoog & R.J. Scheff., Mycologia 76: 297. 1984.

Basionym: Ceratocystis brevicollis R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 50: 667. 1958.

Anamorph: Leptographium brevicolle K. Jacobs & M.J. Wingf., In Jacobs & Wingfield, Leptographium species: 72. 2001.

Phylogenetic information: Sequence data for O. brevicolle from previous studies are contradictory. According to Hausner et al. (2000) O. brevicolle (CBS 150.78 = CMW 474) is closely related to G. francke-grosmanniae. However, Jacobs et al. (2001) showed that O. brevicolle (CBS 795.73 = CMW 447) groups with O. trinacriforme (CBS 210.58 = CMW 670). The GenBank sequences of the two O. brevicolle isolates differ significantly from each other. We have thus chosen to treat O. brevicolle as a species of Ophiostoma until the confusion regarding the species has been resolved.

-

Ceratostomella imperfecta V. V. Mill. & Tcherntz., State For. Tech. Publ. Off. Moscow. p. 123. 1934.

- ≡ Ceratocystis imperfecta (V. V. Miller & Tcherntz.) C. Moreau, Rev. Mycol. (Paris), Suppl. Colon. 17: 22. 1952.

Anamorph: Leptographium (Hunt 1956).

Phylogenetic information: none.

Note: Hunt (1956) suggested, based only on the original description, that this species could be a synonym of G. penicillata. Upadhyay (1981) also lists C. imperfecta as synonym of G. penicillata, apparently based only on the suggestion of Hunt (1956).

-

Ophiostoma obscurum (R.W. Davidson) Hendr., Ann. Gembloux 43: 99. 1937.

Basionym: Ceratostomella obscura R.W. Davidson, J. Agric. Res. 50: 798. 1935.

- ≡ Ophiostoma obscurum (R.W. Davidson) Arx, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 18: 211. 1952. (superfluous combination).

- ≡ Ceratocystis obscura (R.W. Davidson) J. Hunt, Lloydia 19: 30. 1956.

Anamorph: `transitional form between Leptographium and Graphium' (Hunt 1956).

Phylogenetic information: none.

Note: Hunt (1956) treated O. obscurum as a valid species. However, Upadhyay (1981) did not find the teleomorph on the type specimen and treated it as a doubtful species. Its status remains uncertain.

-

Ophiostoma pini (Münch) Syd. & P. Syd., Ann. Mycol. 17: 43. 1917.

Basionym: Ceratostomella pini Münch, Naturwiss. Z. Forst-Landw. 5: 541. 1907.

- ≡ Grosmannia pini (Münch) Goid., Boll. Staz. Patol. Veg. 16: 27. 1936.

- ≡ Ceratocystis pini (Münch) C. Moreau, Rev. Mycol. (Paris), Suppl. Colon. 17: 22. 1952.

Anamorph: Leptographium (Moreau 1952).

Phylogenetic information: none.

Note: Ophiostoma pini has been treated as synonym of O. minus (Hedgcock) H. & P. Sydow by Hunt (1956), Griffin (1968), Olchowecki & Reid (1973), and Upadhyay (1981). Goidánich (1936) placed O. pini in Grosmannia. We have chosen to consider O. pini a synonym of O. minus until phylogenetic data are available to resolve its status more clearly.

-

Ophiostoma rostrocylindricum (R.W. Davidson) Arx, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 18: 212. 1952.

Basionym: Ceratostomella rostrocylindrica R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 34: 658. 1942.

- ≡ Ceratocystis rostrocylindrica (R.W. Davidson) J. Hunt, Lloydia 19: 26. 1956.

Anamorph: Leptographium (Hunt 1956).

Phylogenetic information: none.

Note: Hunt (1956) and Upadhyay (1981) considered this a distinct species, but Jacobs & Wingfield (2001) treated it as doubtful because no type material was designated for it.

-

Ophiostoma trinacriforme (A.K. Parker) T.C. Harr., Mycotaxon 28: 42. 1987.

Basionym: Europhium trinacriforme A.K. Parker, Canad. J. Bot. 35: 175. 1957.

- ≡ Ceratocystis trinacriformis (A.K. Parker) H.P. Upadhyay, In Upadhyay, Monograph of Ceratocystis and Ceratocystiopsis: 63. 1981.

Anamorph: Leptographium trinacriforme K. Jacobs & M.J. Wingf., In Jacobs & Wingfield, Leptographium species: 167. 2001

Phylogenetic information: Hausner et al. (2000) showed that O. trinacriforme (CFB 527) grouped close to O. ips and O. longirostellatum. In the study by Jacobs et al. (2001), O. trinacriforme (CBS 210.58 = CMW 670) grouped close to O. brevicolle, in a clade separate from the two main clades accommodating Leptographium spp. The GenBank sequences for these two O. trinacriforme isolates differ significantly. We have thus chosen to treat it as a species of Ophiostoma until its taxonomic status has been resolved.

-

Ophiostoma truncicolor R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 47: 63. 1955.

- ≡ Ceratocystis truncicola (R.W. Davidson) H.D. Griffin, Canad. J. Bot. 46: 710. 1968.

Anamorph: Graphium-like (Davidson 1955).

Phylogenetic information: none.

Note: Upadhyay (1981) and Seifert et al. (1993) listed O. truncicolor as a synonym of O. penicillatum. The species was not included in the monograph of Leptographium (Jacobs & Wingfield 2001).

-

Ophiostoma valdivianum (Butin) Rulamort, Bull. Soc. Bot. Centre-Ouest, N.S. 17: 192. 1986.

Basionym: Ceratocystis valdiviana Butin, Phytopathol. Z. 109: 86. 1984.

- ≡ Ophiostoma valdivianum (Butin) T.C. Harr., Mycotaxon 28: 42. 1987 (superfluous combination).

Anamorph: Sporothrix and Leptographium (Butin & Aquilar 1984, Seifert et al. 1993).

Phylogenetic information: none.

Note: Jacobs & Wingfield (2001) treated this as a dubious species since no type material or cultures were available for study.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have produced robust phylogenetic data showing that the genus Ophiostoma consists of at least three groups representing separate genera. Based on this phylogenetic evidence and clear morphological characteristics, we have re-instated the teleomorph-genera Ceratocystiopsis and Grosmannia. The former genus now incorporates 11 species including three new combinations, and the latter 27 species including 24 new combinations. The remaining taxa are retained in Ophiostoma even though some monophyletic groups are evident in the larger genus. Because data derived in this study did not provide consistent evidence to support these subgroups amongst the species retained in Ophiostoma, we have chosen not to subdivide the genus further at the present time.

The genus Ceratocystiopsis has been re-instated to accommodate taxa that have short ascomatal necks, produce falcate ascospores with sheaths and have Hyalorhinocladiella (occasionally Sporothrix-like) anamorphs. Upadhyay & Kendrick (1975) established Ceratocystiopsis to separate taxa having these distinct characteristics from taxa residing in the aggregate genus Ceratocystis. Our data revealed a strongly supported, monophyletic lineage with Cop. minuta central to it, and with morphological characters consistent with the original description of Ceratocystiopsis. All species in this group have β-tubulin intron 4 and lack intron 5. This monophyletic group was previously recognised and described as the Minuta complex by Hausner et al. (2003), and the nine species in the complex were characterised by sensitivity to cycloheximide. Amalgamating the data from this study and other published phylogenetic data, Ceratocystiopsis accommodates 11 species.

Hausner et al. (2003) retained their earlier view (Hausner et al. 1993a) that the group treated as Ceratocystiopsis in this study, could not constitute a genus because some species with falcate ascospores did not form part of this lineage. The view here would be that falcate ascospores evolved more than once in the Ophiostomatales. Amongst the species not monophyletic with Cop. minuta, two (Cop. alba, Cornuvesica falcata) are completely unrelated to the Ophiostomatales, no phylogenetic data exist for three species (Cop. conicicollis, Cop. ochracea, Cop. spinulosa), and one has a Leptographium anamorph and resides in Grosmannia (G. crassivaginata). The remaining five species (O. carpenteri, O. crenulatum, O. fasciatum, O. longisporum, O. retusum) are all more closely related to Ophiostoma spp. than to Cop. minuta, and we treat these as species of Ophiostoma. Results of the present study have shown that there is substantial, consistent phylogenetic evidence to support a distinct generic taxon for Ceratocystiopsis.

Grosmannia has been reinstated to accommodate teleomorph taxa that form a monophyletic group including both G. penicillata (type species of Grosmannia) and Leptographium lundbergii (type species of Leptographium). Species in this genus are also characterized by the presence of intron 4 and absence of intron 5 in the β-tubulin gene. Goidánich (1936) established Grosmannia for four species with Scopularia (= Leptographium) anamorphs. However, the genus was not widely recognised and most teleomorph species with Leptographium anamorphs were treated as Ceratostomella, Ceratocystis, Europhium, and more recently, Ophiostoma (Table 1).