Abstract

We have studied mechanisms by which leptin overexpression, which reduces body weight via anorexic and thermogenic actions, induces triglyceride depletion in adipocytes and nonadipocytes. Here we show that leptin alters in pancreatic islets the mRNA of the genes encoding enzymes of free fatty acid metabolism and uncoupling protein-2 (UCP-2). In animals infused with a recombinant adenovirus containing the leptin cDNA, the levels of mRNAs encoding enzymes of mitochondrial and peroxisomal oxidation rose 2- to 3-fold, whereas mRNA encoding an enzyme of esterification declined in islets from hyperleptinemic rats. Islet UCP-2 mRNA rose 6-fold. All in vivo changes occurred in vitro in normal islets cultured with recombinant leptin, indicating direct extraneural effects. Leptin overexpression increased UCP-2 mRNA by more than 10-fold in epididymal, retroperitoneal, and subcutaneous fat tissue of normal, but not of leptin–receptor-defective obese rats. By directly regulating the expression of enzymes of free fatty acid metabolism and of UCP-2, leptin controls intracellular triglyceride content of certain nonadipocytes, as well as adipocytes.

Overexpression of leptin, the adipocyte hormone that regulates body composition through its effects on food intake and energy metabolism (1–5), causes the rapid disappearance of all grossly visible body fat, usually within 1 week (6). In addition, the triglyceride (TG) content of nonadipocyte tissues such as the pancreatic islets is profoundly reduced (7). Because these changes in body fat are unaccompanied by an increase in plasma levels of free fatty acids (FFA) and β-hydroxybutyrate or by ketonuria, we have concluded that the TG must have undergone internal hydrolysis and oxidation within the individual cells (8). This conclusion is supported by in vitro studies showing that leptin lowers the TG content of isolated islets by reducing esterification and by increasing oxidation of FFA (8). It is also consistent with a report that leptin decreases the mRNA and activity of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) (9), which would increase mitochondrial oxidation of FFA by lowering its product, malonyl-CoA (10).

In this study we examine possible mechanisms by which leptin overexpression reduces the TG content of nonadipocytes and adipocytes to unmeasurable levels. Islets are known to express leptin receptor isoforms (7, 11, 12). We therefore compared in pancreatic islets isolated from hyperleptinemic rats and from appropriate euleptinemic controls the mRNA levels of enzymes involved in esterification or oxidation of FFA. In addition, to explain the thermogenic effect of leptin, we examined in both islets and white adipose tissue the mRNA of uncoupling proteins (UCP)-1 and -2, proteins believed to play an important role in regulating thermogenesis (13). White adipocytes are also known to express leptin receptors (14).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Lean wild-type (+/+) male Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats and obese homozygous (fa/fa) male ZDF rats were bred in our laboratory from [ZDF/Drt-fa(F10)] rats purchased from R. Peterson (University of Indiana School of Medicine, Indianapolis). Their genotype was confirmed using the method of Phillips et al. (15). Some of the rats were made hyperleptinemic by the previously described method of leptin gene transfer (6), in which a recombinant adenovirus containing the rat leptin cDNA under control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (AdCMV–leptin) or virus containing the bacterial β-galactosidase gene (AdCMV–β-gal) was administered. Two milliliters of AdCMV-leptin or AdCMV–β-gal containing a total of 1 × 1012 plaque-forming units were infused into lean male homozygous ZDF (+/+) rats over a 30-min period. A third group of rats was infused with only saline. A fourth group of rats was pairfed to the hyperleptinemic rats. Animals were studied in individual metabolic cages, and food intake and body weight were measured daily. On the fourth post-infusion day they were sacrificed. At that time, food intake and body weight in AdCMV–leptin infused rats were significantly below AdCMV–β-gal and saline-infused controls, but body fat had not yet disappeared.

Extraction of Total RNA and Reverse Transcriptase (RT)-PCR Quantitation.

Fat tissue was obtained from epididymal, retroperitoneal, and subcutaneous sites. Pancreatic islets were isolated according to the method of Naber et al. (16). Total RNA was extracted by the TRIzol isolation method (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) from about 100 isolated islets of individual rats. RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase (Promega), and first-strand cDNA was generated from 1 μg of RNA in a 20 μl volume using the oligo(dT) primer in the 1st-strand cDNA synthesis kit (CLONTECH). One microliter of the reverse transcription reaction mix was amplified with primers specific for rat acyl-CoA oxidase (ACO), carnitine palmitoyltransferase (CPT-I), ACC, glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (GPAT), and UCP-2 in a total of 50 μl. All sequences were from the GenBank. Accession numbers and primer and probe sequences are shown in Table 1. Linearity of the PCR reaction was tested by amplification of 200 ng of total RNA per reaction from 15–50 cycles. The linear range was found to be between 15 and 40 cycles. In no case did the amount of RNA used for PCR reaction exceed 200 ng per reaction. The samples were amplified for 25–28 cycles using the following parameters: 92°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. β-actin primers were used as a control. Levels of mRNA were expressed as the ratio of signal intensity for the target genes relative to that for β-actin. The PCR products were electrophoresed on an agarose gel and Southern blotting on a nylon membrane was carried out. Radiolabeled probes (Table 1) specific for each molecule were hybridized to the membrane and quantitated by a molecular imager (Bio-Rad).

Table 1.

Sequences of PCR primers

| Gene | Sense primer (5′–3′) | Antisense primer (5′–3′) | Internal primers (5′–3′, 30-mers) | Size of cDNA, bp | Nucleotide no. | GeneBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | TTGTAACCAACTGGGACGATATGG | GATCTTGATCTTCATGGTGCTAGG | GGTCAGGATCTTCATGAGGTAGTCTGTCAG | 764 | 1552–2991 | J00691J00691 |

| CPT-I | TATGTGAGGATGCTGCTTCC | CTCGGAGAGCTAAGCTTGTC | ACTCTGGTTGGAATCTGACTGGGTGGGATT | 629 | 3094–3722 | L07736L07736 |

| ACO | GCCCTCAGCTATGGTATTAC | AGGAACTGCTCTCACAATGC | GCCTGCACTTTCTTCAGCCATCTTCAACGA | 634 | 2891–3524 | J02752J02752 |

| ACC | ACTCCAGGACAGCACAGATC | TCTGCCAGTCCAATTCTAGC | ATGACATCTCGGCCATCTGGATATTCAGGG | 535 | 4646–5180 | J03808J03808 |

| GPAT | TGATCAGCCAGGAGCAGCTG | AGACAGTATGTGGCACTCTC | CCAAGGAGCACCAGCAATTCATCACCTTTC | 504 | 1827–2330 | M77003M77003 |

| UCP-2 | AACAGTTCTACACCAAGGGC | AGCATGGTAAGGGCACAGTG | GTCATCTGTCATGAGGTTGGCTTTCAGGAG | 471 | 311–782 | U69135U69135 |

Plasma Measurements.

To verify the induction of hyperleptinemia, blood samples were collected from the tail vein in capillary tubes coated with EDTA on the fourth day after adenovirus infusion. Plasma was stored at −20°C until the time of assay. Plasma leptin was assayed using the Linco leptin assay kit (Linco Research Immunoassay, St. Charles, MO). All animals employed in the study exhibited hyperleptinemia in excess of 20 ng/ml. The biological activity of the circulating immunoreactive leptin in AdCMV–leptin-treated animals was reflected on the fourth day by a 45% reduction in food intake and a 15% reduction in body weight compared with AdCMV–β-gal-infused controls.

Islet Culture.

Freshly isolated islets from 7-week-old male lean wild-type ZDF (+/+) rats were cultured in 60-mm Petri dishes at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air as described (17). The culture medium consisted of RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 8.0 mM glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (200 units/ml), streptomycin (0.2 mg/ml), and 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA, fraction V; Miles), either with or without 20 ng/ml of recombinant leptin (kindly provided by Todd Kirchgessner, Bristol–Myers Squibb).

Palmitate Oxidation and Esterification.

Palmitate oxidation was measured by adding 9,10-[3H]palmitate to the culture medium containing the isolated islets, as described previously (18, 19). Total palmitate concentration in the medium was 0.1 mM and the concentration of BSA was 2.0%. After 24 hr in culture, islets were collected and palmitate oxidation assessed by measuring 3H2O in the medium. Excess [3H]palmitate in the medium was removed by precipitating twice with an equal volume of 10% trichloroacetic acid with 2% BSA. Supernatants were transferred to a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube placed in a scintillation vial containing 0.5 ml of unlabeled water and incubated at 50°C for 18 hr. To determine the equilibrium coefficient, 10 μl of 3H2O was added to 490 μl of unlabeled water in 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes in parallel with the experimental samples. Tritiated water was measured as described for usage of [3H]glucose (19).

Palmitate esterification was measured as described (18, 19), except that only 0.1 mM palmitate was employed and the incubation time was shortened to 24 hr.

Statistical Analyses.

All results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA, followed by Scheffe’s multiple comparison test.

RESULTS

FFA Metabolism in Hyperleptinemic Islets.

Recombinant leptin has been shown to reduce the TG content of islets by increasing oxidation and reducing esterification of radiolabeled palmitate in vitro (8). While chronic hyperleptinemia has been demonstrated to reduce the TG content of islets to unmeasurable values in vivo (7, 8), effects on long-chain fatty acid metabolism in islets had not been studied in this model. Consequently, islets were isolated from hyperleptinemic rats and their euleptinemic control groups and cultured in 0.1 mM [3H]palmitate for 24 hr. The esterification rate per 24 hr in islets of hyperleptinemic rats was 33% below pairfed controls, while the rate of oxidation was 92% higher (Table 2). These metabolic changes resemble those induced in cultured islets by recombinant leptin (8), and may account for the marked depletion of fat in the islets of the hyperleptinemic rats. Moreover, they suggested that leptin might deplete TG by up-regulating enzymes of FFA oxidation, and increase thermogenesis by uncoupling oxidation from energy-consuming processes.

Table 2.

Rates of oxidation and esterification of 9,10-[3H]palmitate in islets isolated from AdCMV–β-gal and AdCMV–leptin-infused rats and pairfed controls

| AdCMV–β-gal | AdCMV–leptin | Pairfed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidation (3H2O nmol/hr per islet) | 0.050 ± 0.008 | 0.114 ± 0.025*† | 0.060 ± 0.008 |

| Esterification ([3H]palmitate nmol/hr per islet) | 0.500 ± 0.034 | 0.383 ± 0.038† | 0.568 ± 0.036 |

| Oxidation/esterification, % | 10.4 ± 2.4 | 31.5 ± 9.0*† | 10.4 ± 0.9 |

Values are the mean ± SEM of three experiments.

P < 0.05 vs. AdCMV–β-gal.

P < 0.05 vs. pairfed. Unlabeled palmitate are 0.1 mM in the media.

mRNA Levels of Enzymes Involved in FFA Oxidation and Esterification.

To determine if the metabolic effects of hyperleptinemia were associated with appropriate changes in the expression of the enzymes of long-chain fatty acid metabolism, the ratio of the mRNA encoding each enzyme of interest to that of β-actin mRNA was determined in all groups of rats. The enzymes of interest included two enzymes of FFA oxidation, CPT-I and ACO, and ACC, the product of which, malonyl-CoA, inhibits CPT-I (10), and GPAT, which catalyzes the first step in FFA esterification to TG. In freshly isolated islets from leptin-overexpressing rats CPT-I and ACO mRNA ratios were, respectively, 2.4 and 3.3 times above those of free-feeding AdCMV–β-gal-infused controls and 2.9 and 2.6 times above those of pairfed controls (Fig. 1A). The ACC mRNA ratio of hyperleptinemic islets was reduced to 20% of free-feeding control groups, but a similar reduction was also observed in pairfed ACC controls. The foregoing changes in CPT-I and ACO would be consistent with leptin-mediated up-regulation of enzymes required for mitochondrial and peroxisomal oxidation of FFA independently of the leptin-mediated reduction in intake. However, the reduction of ACC mRNA was observed in rats that were pairfed to hyperleptinemic rats, as well as in hyperleptinemic rats; this suggests that it was, at least in part, the result of the restricted caloric intake.

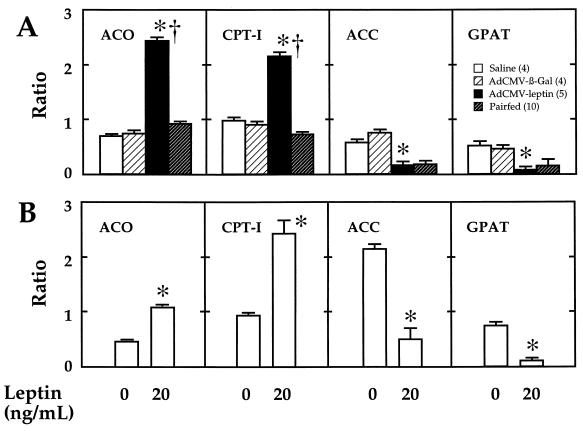

Figure 1.

(A) Ratios of mRNA of ACO, CPT-I, ACC, and GPAT to mRNA of β-actin in islets isolated from hyperleptinemic rats infused with AdCMV–leptin, pairfed controls, free-feeding AdCMV–β-gal controls, and saline-infused controls. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of rats studied. *, P < 0.001 vs. AdCMV–β-gal-infused rats. †, P < 0.001 vs. pairfed rats. (B) Ratios of mRNA of ACO, CPT-I, ACC, and GPAT to mRNA of β-actin in normal rat islets cultured for 48 hr in either 0 or 20 ng/ml of recombinant leptin. *, P < 0.001 vs. 0 leptin. Values are the mean ± SEM of three individual experiments.

The GPAT/β-actin mRNA ratio of leptin-overexpressing rats was reduced to 16% of free-feeding β-gal controls, but it also was reduced in pairfed rats to 29% of the level in saline-infused controls. This is consistent with dual control by food intake and also by a mechanism independent of food intake.

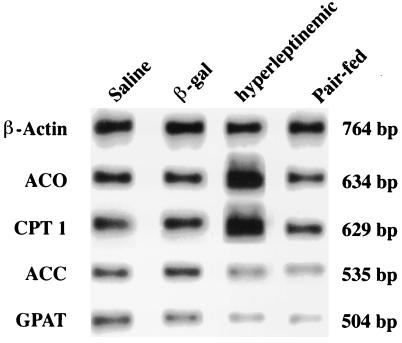

Representative Southern blots of RT-PCR products appear in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Representative Southern blot of RT-PCR products for enzymes of fatty acid metabolism, ACO, CPT-I, ACC, and GPAT in islets isolated from rats made hyperleptinemic by AdCMV–leptin infusion and pairfed controls and AdCMV–β-gal and saline-infused free-feeding controls.

In Vitro Effects of Leptin on Enzymes of FFA Oxidation and Esterification in Pancreatic Islets.

To determine if the foregoing changes that occurred in vivo were, at least in part, independent of the hypothalamic pathway of leptin action, we cultured islets with or without recombinant leptin in the medium. The 20 ng/ml leptin concentration employed was similar to the plasma level in hyperleptinemic rats, which averaged 20 ng/ml. Qualitatively identical results were observed in normal islets cultured for 2 days in the presence or absence of 20 ng/ml of recombinant leptin (Fig. 1B). The mRNA ratio for ACO and CPT-I were both significantly increased (P < 0.001), whereas those for ACC and GPAT were significantly reduced (P < 0.001).

mRNA Levels of UCP-2 in Hyperleptinemia.

There was no evidence that energy generated in the hyperleptinemic rats by the increased oxidation of fat was being channeled into energy-requiring processes (6, 8). This suggested that the leptin-stimulated increase in FFA oxidation was uncoupled. Since we found no evidence for ectopic expression of the UCP-1 of brown adipose tissue in islets or other tissues (data not shown), we searched for increased levels of uncoupling protein-2 (UCP-2), the recently discovered and widely expressed protein with a 59% amino acid homology to UCP-1 (13). It has been presumed that UCP-2, like UCP-1, forms a pathway for proton flux from cytosol to mitochondrial matrix.

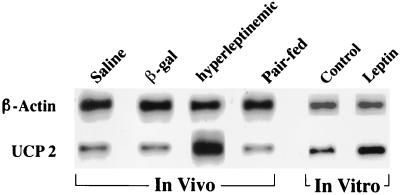

UCP-2 mRNA in islets of hyperleptinemic rats was over 10 times greater than in islets of pairfed controls and over 6 times that of free-feeding AdCMV–β-gal controls (Fig. 3; Table 3). Islets cultured for 48 hr in 20 ng/ml of leptin exhibited a 3.6-fold increase in UCP-2 mRNA (1.25 vs. 0.34). Representative Southern blots of products of RT-PCR for UCP-2 are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Representative Southern blot of RT-PCR products for UCP-2 in islets isolated from leptin-overexpressing rats, pairfed controls, and AdCMV–β-gal- and saline-infused free-feeding controls. In vitro effects of 20 ng/ml leptin on UCP-2 mRNA in cultured islets are also shown.

Table 3.

Comparison of UCP-2 mRNA expression in pancreatic islets isolated from saline, AdCMV–β-gal, and AdCMV–leptin infused rats and pairfed controls

| Saline | AdCMV–β-gal | AdCMV–leptin | Pairfed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lean +/+ ZDF | 0.3 ± 0.7 (3) | 0.3 ± 0.04 (3) | 1.9 ± 0.2 (5)*† | 0.2 ± 0.02 (3) |

Values are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Number of experiments are in parentheses.

*P < 0.001 vs. AdCMV–β-gal.

P < 0.001 vs. pairfed.

Effect of Leptin on UCP-2 mRNA of White Adipocytes in Vivo.

Because of the interest in the diabetogenic effects of obesity (20–22), we have focused on the pancreatic islets as a target tissue for direct leptin action. But since the most dramatic component of the hyperleptinemic phenotype is the disappearance of all identifiable fat tissue within 7 days of the infusion of the AdCMV–leptin (6), we also collected epididymal, retroperitoneal, and subcutaneous white fat tissue on the fourth day while it was still identifiable, and measured UCP-2 mRNA.

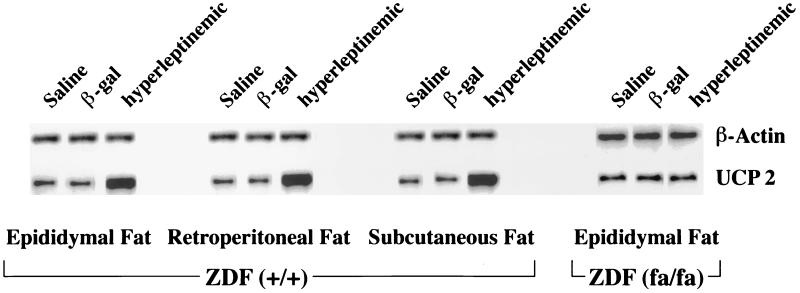

The epididymal, retroperitoneal, and subcutaneous white adipose tissue of leptin-overexpressing rats all exhibited a 4.6-fold increase in the mRNA ratio of UCP-2 to β-actin, compared with free-feeding control rats (Table 4). However, in epididymal fat from obese leptin-resistant ZDF rats homozygous (fa/fa) for the mutation in the leptin receptor (14, 15). AdCMV–leptin-induced hyperleptinemia failed to increase UCP-2 mRNA above that of AdCMV–β-gal-infused controls (Table 4). Representative Southern blots of RT-PCR products are shown in Fig. 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of UCP-2 mRNA expression in fat tissues isolated from saline, AdCMV–β-gal, and AdCMV–leptin infused rats

| Tissue | Saline | AdCMV–β-gal | AdCMV–leptin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lean +/+ ZDF | |||

| Epidydimal | 0.6 ± 0.15 (3) | 0.5 ± 0.06 (3) | 2.6 ± 0.3 (3)* |

| Retroperitoneal | 0.5 ± 0.06 (3) | 0.5 ± 0.1 (3) | 2.5 ± 0.4 (3)* |

| Subcutaneous | 0.5 ± 0.11 (3) | 0.5 ± 0.06 (3) | 2.5 ± 0.2 (3)* |

| Obese fa/fa ZDF | |||

| Epidydimal | 0.498 (2) | 0.377 (1) | 0.407 ± 0.065 (3) |

Values are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Number of experiments are in parentheses.

*P < 0.001 vs. AdCMV–β-gal.

Figure 4.

Representative Southern blot of the UCP-2 RT-PCR products in white adipose tissue from subcutaneous, retroperitoneal, and epididymal fat depots of hyperleptinemic rats and pairfed controls and free-feeding AdCMV–β-gal- and saline-infused controls.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies (6, 8) suggest that nonadipocytes normally contain a small quantity of TG. This TG supply may be a vestige of a period in phylogenesis before the evolution of adipocytes when each cell carried its own TG reservoir. While the evolution of adipocytes may have rendered superfluous the energy storage function of the TG reservoir of nonadipocytes, there is evidence that the intracellular fat store may provide an internal source of FFA for various intracellular signaling functions. For example, normal islets contain approximately 24 ng of TG per islet and when they are depleted of fat by hyperleptinemia, the insulin response to glucose and other fuels is completely abolished (7). It is promptly restored by FFA. The size of the TG reservoir appears to be under the control of leptin. Islets of obese, leptin-resistant ZDF rats contain 990 ng of TG per islet (20); in rats with hyperleptinemia islet TG is zero (7, 8).

The rapid disappearance of body fat without a rise in plasma FFA, β-hydroxybutyrate or urine ketones in hyperleptinemia (8), is in contrast to the rise in FFA and ketones that accompanies fat loss caused by starvation or insulin deficiency (10). This difference pointed to leptin-regulated internal control of the intracellular fat pool in adipocytes and nonadipocytes alike. If this is correct, tissues of hyperleptinemic rats should exhibit an increased rate of FFA oxidation and a low rate of esterification, as had been reported when normal islets were cultured in the presence of leptin (8). Such changes were in fact found in islets from hyperleptinemic rats. Since they did not occur in islets of pairfed rats, the changes in FFA metabolism were independent of the reduction in caloric intake.

We therefore searched for leptin-induced changes in the expression of genes encoding the enzymes involved in oxidation and esterification of FFA and of a gene suspected to be involved in thermogenesis. mRNA for enzymes of FFA oxidation was significantly increased; ACO mRNA was more than 3 times as high in islets of hyperleptinemic rats as in free-feeding AdCMV–β-gal-infused controls and 2.6 times the level in pairfed controls, and CPT-I mRNA was almost 3 times as high. Induction by leptin of these two key enzymes of FFA oxidation was clearly independent of the reduction in caloric intake.

By contrast, the mRNA of ACC, an enzyme that, by generating malonyl-CoA inhibits CPT-I activity (10), was profoundly reduced to 21% of free-feeding AdCMV–β-gal-infused controls. However, it was also reduced in islets of pairfed rats to 23% of controls. This indicates that dietary restriction reduces ACC expression. Nevertheless, the in vitro studies demonstrate a direct down-regulation of ACC by leptin that may have been concealed in vivo by dietary down-regulation of ACC mRNA to undetectable levels.

mRNA of GPAT, an enzyme of FFA esterification, was reduced in the islets of hyperleptinemic rats to 16% of free-feeding β-gal controls. However, it was also reduced in pairfed rats to 33% of the control levels, despite a 50% decline in plasma leptin levels (6). Thus, it appears that both reduction in food intake and a direct effect of leptin participate in the down-regulation of GPAT in hyperleptinemic rats.

Until recently the thermogenic effects of leptin were thought to be confined to brown adipose tissue, the major site of UCP-1 expression. However, the recent discovery of UCP-2 (13), a far more ubiquitously expressed protein, raised the possibility that hyperleptinemia might up-regulate UCP-2 in tissues that express the leptin receptor OB-R. UCP-2 mRNA was identified in islets of normal and hyperleptinemic rats and was expressed in the latter at over 10 times the level of pairfed controls; in the latter group, UCP-2 mRNA declined below the levels in free-feeding saline-infused controls (0.17 ± 0.2 vs. 0.33 ± 0.07). Thus, up-regulation of UCP-2, like the up-regulation of ACO and CPT-I, was independent of the anorexic action of leptin. Qualitatively identical induction of UCP-2 by leptin was observed in vitro in cultured islets from normal rats. This suggests that, at least in this unphysiologic model of leptin overexpression, the effects of leptin observed in vivo may in large part represent direct actions not mediated via the hypothalamus. Finally, UCP-2 mRNA was increased in the subcutaneous retroperitoneal and epididymal fat tissue of hyperleptinemic lean rats, but not of leptin-resistant obese ZDF (fa/fa) rats. These findings obtained by RT-PCR were confirmed by RNA blot hybridization (data not shown).

Still to be elucidated are the mechanisms by which leptin induces these changes. Because FFA may serve as a ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, one must entertain the possibility that leptin first activates an unidentified intracellular lipase that increases intracellular FFA and exerts its effects on gene expression via these nuclear receptors. This idea is supported by the fact that troglitazone, reported to be a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ ligand (23–25), also increases UCP-2 mRNA in islets (M.S., Y.-T.Z., and R.H.U., unpublished data).

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Kay McCorkle for outstanding technical support. Sharryn Harris provided excellent secretarial support. We thank Michael S. Brown for critical examination of the manuscript. We also thank J. Denis McGarry for his stimulating leadership in the field of lipid metabolism. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 5-RO1-DK02700-38, Department of Veterans Affairs Institutional Research Support Grant SMI 821-109, and a National Institutes of Health/Juvenile Diabetes Foundation Diabetes Interdisciplinary Research Program Grant.

ABBREVIATIONS

- TG

triglyceride

- FFA

free fatty acid(s)

- ACC

acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- CPT-I

carnitine palmitoyltransferase

- ACO

acyl-CoA oxidase

- GPAT

glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase

- UCP-1 and -2

uncoupling proteins 1 and 2

- ZDF

Zucker diabetic fatty

- β-gal

β-galactosidase

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

References

- 1.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman J. Nature (London) 1994;372:425–432. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pellymounter M A, Cullen M J, Baker M B, Hecht R, Winters D, Boone T, Collins F. Science. 1995;269:540–543. doi: 10.1126/science.7624776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campfield L, Smith F, Guisez Y, Devos R, Burn P. Science. 1995;269:546–548. doi: 10.1126/science.7624778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maffei M, Halaas J, Ravussin E, Pratley R E, Lee G H, Zhang Y, Fei H, Kim S, Lallone R, Ranganathan S, Kerm P S, Friedman J M. Nat Med. 1995;1:1155–1161. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halaas J, Gajiwala K, Maffei M, Cohen S, Chait B, Rabinowitz D, Lallone R, Burley S. Science. 1995;269:543–546. doi: 10.1126/science.7624777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen G, Koyama K, Yuan X, Lee Y, Zhou Y T, O’Doherty R, Newgard C B, Unger R H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14795–14799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koyama, K., Chen, G., Wang, M.-Y., Lee, Y., Shimabukuro, M., Newgard, C. B. & Unger, R. H. (1997) Diabetes, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Shimabukuro M, Koyama K, Chen G, Wang M-Y, Trieu F, Lee Y, Newgard C B, Unger R H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4637–4641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bai Y, Zhang S, Kim K-S, Lee J-K, Kim K-H. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13939–13942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.13939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGarry J D, Foster D W. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:395–420. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.002143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tartaglia L A, Dembski M, Weng X, Deng N, Culpepper J, Devos R, Richards G J, Campfield L A, Clark F T, Deeds J, Muir C, Sanker S, Moriarty A, Moore K J, Smutko J S, Mays G G, Woolfe E A, Monroe C A, Tepper R I. Cell. 1995;65:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kieffer T J, Heller R S, Habener J F. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224:522–527. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleury C, Neverova M, Collins S, Raimbault S, Champigny O, Levi-Meyrueis C, Bouillard F, Seldin M, Surwit R S, Ricquier D, Warden C. Nat Genet. 1997;15:269–272. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iida M, Murakami T, Ishida K, Mizuno A, Kuwajima M, Shima K. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224:597–604. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips M S, Liu Q Y, Hammond H A, Dugan V, Hey P J, Caskey C T, Hess J F. Nat Genet. 1996;13:18–19. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naber S P, McDonald J M, Jarett L, McDaniel M L, Ludvigsen C W, Lacy P E. Diabetologia. 1980;19:439–444. doi: 10.1007/BF00281823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milburn J L, Hirose H, Lee Y, Nagasawa Y, Ogawa A, Ohneda M, Beltrandel-Rio H, Newgard C, Johnson J H, Unger R H. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1295–1299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen S, Ogawa A, Ohneda M, Unger R H, Foster D W, McGarry J D. Diabetes. 1994;43:878–883. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.7.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee Y, Hirose H, Zhou Y-T, Esser V, McGarry J D, Unger R H. Diabetes. 1997;46:408–413. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee Y, Hirose H, Ohneda M, Johnson J H, McGarry J D, Unger R H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10878–10882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unger R H. Diabetes. 1995;44:863–870. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.8.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirose H, Lee Y, Inman L R, Nagasawa Y, Johnson J H, Unger R H. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5633–5637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tontonoz P, Hu E, Graves D A, Budauon A L, Spiegelman B M. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1224–1234. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.10.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehmann J M, Moore L B, Smith-Oliver T A, Wilkison W O, Willson T M, Kliewer S A. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12953–12956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spiegelman B M, Flier J S. Cell. 1996;87:377–389. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81359-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]