Abstract

Background

Epithelial lining fluid plays a critical role in protecting the lung from oxidative stress, in which the oxidised status may change by ageing, smoking history, and pulmonary emphysema.

Methods

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed on 109 young and older subjects with various smoking histories. The protein carbonyls, total and oxidised glutathione were examined in BAL fluid.

Results

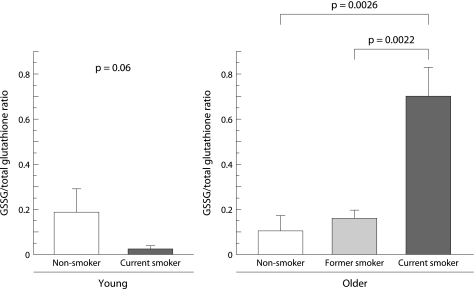

By Western blot analysis, the major carbonylated protein in the BAL fluid was sized at 68 kDa, corresponding to albumin. The amount of carbonylated albumin per mg total albumin in BAL fluid was four times higher in older current smokers and three times higher in older former smokers than in age matched non‐smokers (p<0.0001, p = 0.0003, respectively), but not in young smokers. Total glutathione in BAL fluid was significantly increased both in young (p = 0.006) and older current smokers (p = 0.0003) compared with age matched non‐smokers. In contrast, the ratio of oxidised to total glutathione was significantly raised (72%) only in older current smokers compared with the other groups. There was no significant difference in these parameters between older smokers with and without mild emphysema.

Conclusions

Oxidised glutathione associated with excessive protein carbonylation accumulates in the lung of older smokers with long term smoking histories even in the absence of lung diseases, but they are not significantly enhanced in smokers with mild emphysema.

Keywords: bronchoalveolar lavage, protein carbonyls, antioxidant, glutathione, smoking, ageing

The lung is an organ constantly exposed to exogenous oxidants such as cigarette smoke and air pollutants. Epithelial lining fluid (ELF) acts as an interface between the airspace epithelium and the external environment and therefore affords protection against epithelial cell injury.1 Because the constituents of ELF form the primary targets of inhaled oxidant pollutants and also inflammatory reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated within the alveolar space, the oxidative modifications of certain extracellular targets and their functional consequences have received considerable attention.2 It is known that protein carbonylation reflects the oxidation of Lys, Arg, or Pro residues in proteins. The content of protein carbonyls is therefore by far the most commonly used marker for protein oxidation.3

On the other hand, there are various kinds of extracellular antioxidants in the lungs such as mucin, uric acid, ascorbic acid, α‐tocopherol, glutathione, antioxidant enzymes and proteins that are capable of binding metals. Glutathione is a sulfhydryl‐containing tripeptide (l‐gamma‐glutamyl‐l‐cysteinyl‐glycine) that is present in high concentrations in all cells and protects against intracellular oxidants and xenobiotics.4 Extracellular glutathione can be augmented by cellular sources from respiratory tract epithelial cells and inflammatory cells such as macrophages. The levels of glutathione in ELF are 100‐fold higher than in plasma, which may indicate its relative importance among the various antioxidants.4,5

The elderly are particularly vulnerable to smoking associated respiratory diseases. Worldwide, the ratio of smokers is still high among the middle aged or elderly population, and they usually have long term smoking histories. Cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for the development of emphysema, and it normally affects patients in the fifth to sixth decade of life. Although an oxidant/antioxidant imbalance has been implicated in the development of emphysema,6 there is still a large gap in our understanding of the link between the cumulative effects of ageing and decades of continuous smoking on the oxidative stress and antioxidant mechanisms in the lung. Total glutathione is known to be raised in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of recent young smokers, and the majority (>95%) of the total glutathione is maintained in the reduced state.5 However, there is a lack of information on the levels and redox state of glutathione in the BAL fluid of older smokers with or without pulmonary emphysema.

We therefore investigated whether chronic smoking induced changes in protein carbonylation and glutathione redox status in BAL fluid differ by age, duration of smoking, or the presence of emphysema. BAL was performed to obtain ELF from lifelong non‐smokers as well as young and older smokers with various smoking histories.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 109 community based asymptomatic volunteers were recruited from the patients in our smoking cessation and non‐pulmonary clinics and from the employees and students in our medical school. Most of the subjects had taken part in previous studies in our laboratory.7,8 The young group (age 20–29 years, n = 39) consisted of 16 lifelong non‐smokers and 23 current smokers who had smoked for less than 3 years. The older group (age 37–77 years, n = 70) included seven lifelong non‐smokers, 17 former smokers, and 46 current smokers with smoking histories of more than 20 years. Former smokers were arbitrarily defined as people who had quit smoking for at least 1 year. None of the subjects was on regular medication or had a history of asthma or other allergic disorders. All subjects had been free of clinically apparent respiratory infections for the preceding 2 months and had been evaluated by physical examination, chest radiography, and a blood test. After elimination of non‐eligible subjects, all older former and current smokers were screened for emphysematous changes by high resolution computed tomographic (HRCT) scanning as previously described.9 Pulmonary function tests were performed in accordance with the standard techniques of the American Thoracic Society. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) from the flow‐volume curve was expressed as a percentage of the predicted value according to the equations of Berglund et al.10

All of the subjects provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the ethics committee of Hokkaido University School of Medicine.

Sequential BAL

Sequential BAL was performed through a wedged flexible fibreoptic bronchoscope (Olympus BF‐B3R, Tokyo, Japan) as described previously.9 The fluid returned from the first 50 ml aliquot was not used in the study. The remaining lavage fluid was pooled and used as the BAL fluid. Differential cell counts were performed as previously described.9 The level of total protein in the BAL fluid was determined using a Micro BCA Protein Assay Reagent kit (Pierce Biotech, IL, USA). The level of albumin was quantified by laser nephelometry as described previously.9 The level of transferrin was measured using the human transferrin enzyme linked immunosorbent assay quantification kit (Bethyl Laboratories Inc, TX, USA).

Assessment of protein carbonyls in BAL fluid

Oxidation of individual BAL fluid proteins was measured by analysis of Western blots according to the method of Shacter et al.11 BAL fluid was derivatised with dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNP) using the OxyBlot Protein Oxidation Detection kit (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA) with slight modification. Briefly, 16 μl of unconcentrated BAL fluid were denatured by adding 3 μl of 20% sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS)‐polyacrylamide, derivatised by adding 1 μl 10X DNPH solution, and neutralised by adding 7.5 μl neutralization solution and 1.5 μl 2‐mercaptoethanol. Samples were separated by electrophoresis on 10% SDS‐polyacrylamide electrophoresis gels. Blots were performed using the anti‐DNP antibody and scanned with a GT‐9500 scanner (Epson, Nagano, Japan); the intensity of the bands was calculated using NIH Image software (version 1.62). On each blot the recorded total DNP intensity of all bands detected for each lane was divided by that of a standard sample from a representative young non‐smoker. The total carbonyl content in the BAL fluid was referred as total DNP units/ml BAL fluid. The assay for the total carbonyl content had an intrabatch coefficient of variation of 12% (n = 7) and an interbatch coefficient of variation of 16% (n = 5).

The molecular masses of albumin and transferrin were determined by Western blotting on the same membrane used for the Oxyblot. Specifically, after the Western blot for carbonyl proteins, the anti‐DNP antibody was removed, then incubated with 1:1000 peroxidase conjugated anti‐human albumin antibody (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) or 1:1000 rabbit anti‐human transferrin (Dakocytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) followed by 1:15 000 horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti‐rabbit antibody (DAKO). Sites of antibody binding were visualised using the ECLPlus Western blotting detection system (Amersham, Aylesbury, UK).

Measurement of total glutathione and glutathione disulfide in BAL fluid

Total glutathione and glutathione disulfide (GSSG), oxidised glutathione, were measured in all samples using a glutathione assay kit (Cayman Chemical Co, MI, USA) as described by Tietze and co‐workers.12 The assays for total glutathione and GSSG had intrabatch coefficients of variation of 3% (n = 12) and 3% (n = 10), respectively, and interbatch coefficients of variation of 6% (n = 10) and 13% (n = 8), respectively.

Statistical analyses

Differences between the two means were performed with a two tailed unpaired Student's t test using Statview Software (SAS Institute Inc, NC, USA). More than two means were compared by analysis of variance followed by the Games‐Howell method using SAS software Version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc). A value of p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The results are reported as standard error of the mean (SE).

Results

Characteristics of subjects

Clinical characteristics and pulmonary function data for the subjects are summarised in table 1. Emphysema, as detected on CT scans, was less than 25% of the total lung area in most subjects categorised in the emphysema groups. There was no difference in the number of cigarettes smoked per day between young and older current smokers.

Table 1 Characteristics of subjects.

| Young | Older | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non‐ smokers | Current smokers | Non‐ smokers | Former smokers | Current smokers | |||

| No emphysema | Emphysema | No emphysema | Emphysema | ||||

| No of subjects | 16 | 23 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 21 | 25 |

| Age (years) | 23 (1) | 23 (0) | 63 (3) | 65 (2) | 59 (3) | 57 (2) | 61 (2) |

| Cigarettes/day | 0 | 20 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 (5) | 25 (4) |

| Pack‐years | 0 | 5 (1) | 0 | 35 (10) | 41 (7) | 55 (5) | 45 (4) |

| VC (% pred) | 97 (3) | 96 (3) | 122 (8) | 125 (3) | 110 (3)† | 110 (4) | 110 (4) |

| FEV1 (% pred) | 83 (3) | 88 (3) | 124 (8) | 129 (5) | 97 (5)† | 101 (5) | 92 (4)‡ |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 91 (2) | 88 (2) | 84 (2) | 80 (2) | 73 (3)* | 79 (2) | 70 (2)*‡ |

VC, vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Data are expressed as mean (SE).

*Significantly different from older non‐smokers (p<0.05).

†Significantly different from older former smokers without emphysema (p<0.05).

‡Significantly different from older current smokers without emphysema (p<0.05).

BAL findings

BAL findings are shown in table 2. The total protein, albumin, and transferrin levels in BAL fluid from young smokers were significantly lower than those from young non‐smokers. There were no differences in the levels of total protein, albumin, and transferrin in BAL fluid among older groups. The numbers of total cells and macrophages in BAL fluid were significantly increased in current smokers compared with non‐smokers, both in young and older groups. The percentage of macrophages and neutrophils in BAL fluid did not differ between young and older current smokers.

Table 2 BAL fluid findings.

| Young | Older | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non‐ smokers | Current smokers | Non‐ smokers | Former smokers | Current smokers | |||

| No emphysema | Emphysema | No emphysema | Emphysema | ||||

| Recovery rate (%) | 74 (4) | 64 (3)* | 71 (4) | 54 (5) | 33 (5)† ‡ | 50 (4)† | 33 (5)†§ |

| Albumin (mg/l) | 47 (7) | 33 (3)* | 55 (9) | 57 (11) | 59 (11) | 32 (2) | 50 (10) |

| Total protein (mg/l) | 116 (14) | 92 (7)* | 160 (22) | 128 (28) | 210 (44) | 111 (10) | 142 (13) |

| Transferrin (mg/l) | 3.8 (0.4) | 2.9 (0.2)* | 7.4 (2.0) | 4.3 (1.2) | 4.5 (1.1) | 3.9 (0.4) | 3.6 (0.3) |

| Total cells (×10−4/ml) | 8.1 (0.9) | 20.1 (2.2)* | 13.4 (1.3) | 9.6 (2.4) | 10.5 (3.4) | 27.3 (4.3)† | 36 (8.2)† |

| Macrophages (×10−4/ml) | 6.9 (0.9) | 19.5 (2.1)* | 10.8 (1.3) | 8.0 (1.9) | 8.4 (2.4) | 25.9 (4.1)† | 32.9 (8.0)† |

| Neutrophils (×10−4/ml) | 0.20 (0.05) | 0.24 (0.08) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.06 (0.02) | 0.62 (0.45) | 0.59 (0.25) |

Data are expressed as mean (SE).

*Significantly different from young non‐smokers (p<0.05).

†Significantly different from older non‐smokers (p<0.05).

‡Significantly different from older former smokers without emphysema (p<0.05).

§Significantly different from older smokers without emphysema (p<0.05).

Total protein carbonyls in BAL fluid

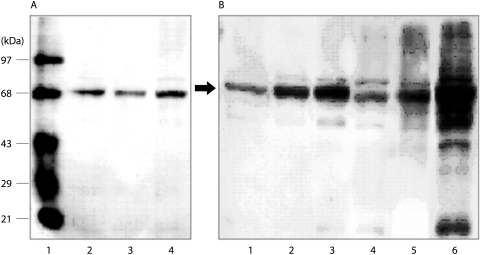

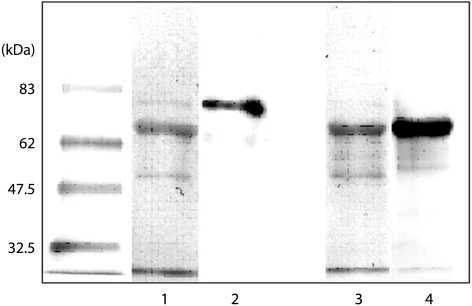

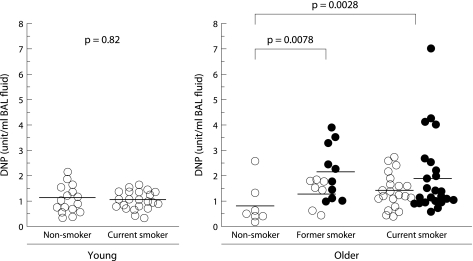

The immunoblot analysis demonstrated a major carbonyl protein band for all of the subjects with a molecular weight of 68 kDa (fig 1A and B) and a faint band of 80 kDa for most of the subjects. These bands were speculated to be albumin and transferrin, respectively, based on removal of the anti‐DNP antibody followed by Western blotting with antibodies against human albumin or human transferrin (fig 2). As shown in fig 3, the total DNP in units/ml BAL fluid from older current and former smokers was significantly higher than in lifelong non‐smokers of the same age (1.72 (0.18) and 1.81 (0.24) v 0.7 (0.29) unit/ml; p = 0.0028 and p = 0.0078, respectively). In contrast, no difference was found in the total DNP units/ml BAL fluid between non‐smokers and current smokers among the young subjects (1.05 (0.14) v 1.0 (0.09) units/ml, p = 0.82). There was also no difference between former smokers with and without emphysema (2.16 (0.34) v 1.32 (0.22) units/ml, p = 0.08) or between current smokers with and without emphysema (2.00 (0.31) v 1.44 (0.14) units/ml, p = 0.15).

Figure 1 Representative Western blots of oxidised protein in BAL fluid. (A) Representative Western blots from young subjects. Lane 1, molecular weight protein standards in which the second band from the top (68 kDa) is bovine serum albumin; lane 2, a young non‐smoker; lane 3, a young current smoker; lane 4, a young non‐smoker which was used as a standard for each blot. (B) Representative blots from older subjects. Lane 1, standard BAL sample also shown in lane 4 of (A); lanes 2 and 3, older current smokers without emphysema; lane 4, older non‐smoker; lanes 5 and 6, older current smokers with emphysema.

Figure 2 Immunoblots for transferrin and albumin in BAL fluid. After removal of the anti‐DNP antibody, Western blotting was carried out on the same membrane. Lanes 1 and 3, anti‐DNP antibody; lane 2, anti‐human transferrin antibody; lane 4, anti‐human albumin antibody. The positions of the molecular weight standards are shown on the left.

Figure 3 Total DNP units/ml in BAL fluid. Horizontal lines represent mean values of each group. Open circles represent subjects without emphysema; closed circles represent subjects with emphysema. DNP, dinitrophenylhydrazine.

Albumin carbonylation in BAL fluid

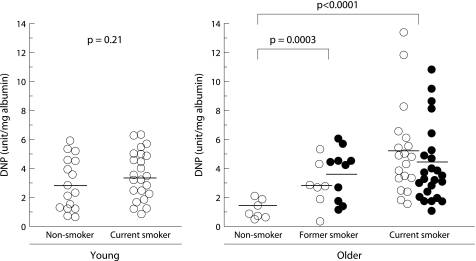

To focus on the carbonylation of albumin, DNP units of the 68‐kDa band (corresponding to albumin) were quantified. The value was normalised according to the concentration of albumin in the BAL fluid (fig 4). The ratio of carbonylated albumin per mg total albumin was four times higher in older current smokers and three times higher in older former smokers than in age matched lifelong non‐smokers (fig 4). In contrast, there was no difference in the ratio of albumin carbonylation in BAL fluid between young smokers and non‐smokers (p = 0.21). In both current and former smokers there was no difference in the ratio of albumin carbonylation between the subjects with and without emphysema.

Figure 4 Carbonylated albumin/mg total albumin in BAL fluid. The horizontal lines represent mean values of each group. Open circles represent subjects without emphysema; closed circles represent subjects with emphysema. DNP, dinitrophenylhydrazine.

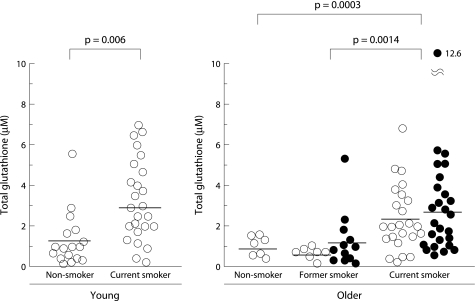

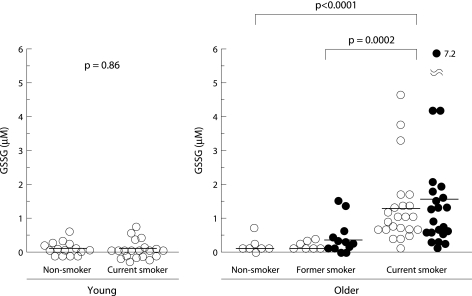

Total glutathione and GSSG in BAL fluid

Total glutathione was detected in unconcentrated BAL fluid for all subjects (fig 5). The concentration of total glutathione in BAL fluid was significantly increased in smokers compared with non‐smokers, even in young subjects (3.11 (0.4) v 1.17 (0.33) μg/ml, p = 0.006). It was also significantly increased in older current smokers compared with age matched non‐smokers and former smokers (2.64 (0.34) v 0.89 (0.19) and 0.88 (0.29) μg/ml, p = 0.0003 and p = 0.0014, respectively). In contrast, the level of GSSG was markedly raised only in older current smokers (1.38 (0.2) μg/ml) and was mostly under the detection limit in the other groups (fig 6). No significant difference was observed between former or current smokers with and without emphysema either in the level of total glutathione in BAL fluid (former smokers: 1.15 (0.47) v 0.49 (0.12) μg/ml, p = 0.23; current smokers: 2.78 (0.55) v 2.46 (0.38) μg/ml, p = 0.64) or in the level of GSSG in BAL fluid (former smokers: 0.28 (0.13) v 0.09 (0.05) μg/ml, p = 0.27; current smokers: 1.48 (0.38) v 1.28 (0.26) μg/ml, p = 0.67, respectively). The ratio of GSSG per total glutathione in older current smokers was as high as 0.72 and was significantly higher than in the other groups (fig 7).

Figure 5 Levels of total glutathione in BAL fluid. The horizontal lines represent mean values of each group. Open circles represent subjects without emphysema; closed circles represent subjects with emphysema.

Figure 6 Levels of glutathione disulfide (GSSG) in BAL fluid. The horizontal lines represent mean values of each group. Open circles represent subjects without emphysema; closed circles represent subjects with emphysema.

Figure 7 Glutathione disulfide (GSSG)/total glutathione ratio in BAL fluid. Data are mean (SE) values for each group.

Discussion

In this study we have shown that older smokers with a long term history of smoking have excessive protein carbonyls and accumulate GSSG in BAL fluid, indicating that endogenous antioxidant defences are overwhelmed. Based on the number of cigarettes smoked per day, the amount of exogenous ROS from cigarette smoke was similar for all current smokers regardless of their age; however, the young and older current smokers undoubtedly developed different levels of oxidative stress in the lungs. On the other hand, ageing alone did not affect the level of protein carbonyls, total glutathione, or GSSG in BAL fluid.

The reaction of ROS with proteins results in the formation of carbonyl groups on amino acid residues. Oxidative stress overwhelming the antioxidant defence of the lung may lead to lung injury through a variety of mechanisms including lipid peroxidation of epithelial cell membranes.13,14 Total protein carbonyls are reportedly increased in the BAL fluid from patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome,15 idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, sarcoidosis, asbestosis,16 and cystic fibrosis.17 Notably, we found in this study that the level of total protein carbonyls in BAL fluid was raised not only in older current smokers but also in older former smokers despite not smoking for at least a year, indicating that the mechanisms responsible for increased protein carbonyls associated with smoking persist after cessation.

To clarify how protein oxidation participates in pathogenic processes, it will be important to identify the organ and/or disease specific proteins that are most susceptible to oxidative modification and the functional effects of their oxidation. Albumin and transferrin in the serum of mice and albumin and α1‐macroglobulin in the serum of rats accrue significant levels of carbonylation.18 In the plasma of humans, albumin, fibrinogen, and both fibrinogen γ‐chain and α1‐antitrypsin precursors are major targets for carbonylation in uraemia,19 lung cancer,20 and Alzheimer's disease,21 respectively. We report here for the first time that the oxidation of albumin—the most abundant protein in BAL fluid—mostly accounts for excessive total protein carbonylation in older smokers. It is plausible that albumin in BAL fluid from older current smokers may lose its functional efficiency as a consequence of carbonylation because oxidative modifications of albumin reportedly attenuate its antioxidative capacity.22

Glutathione also functions as an extracellular antioxidant of the lungs by preventing the oxidation of functional surfactants and antioxidant enzymes only in its reduced form (GSH).5,23 GSH inhibits protein carbonyl formation in plasma following exposure to cigarette smoke.24 Although the concentration of total glutathione in BAL fluid is known to vary between lung diseases, the presence of its oxidised form in BAL fluid has only been studied in asthma,25 cystic fibrosis,26 and acute respiratory distress syndrome.27 In the BAL fluid of acute respiratory distress syndrome patients, a significant portion of the total glutathione is in the oxidised form (GSSG), which is likely to be due to the rapid extracellular oxidation of glutathione.27

Although the regulation of glutathione in BAL fluid is poorly understood, we speculate that GSSG accumulates in BAL fluid in older smokers by the following mechanisms. Firstly, the extracellular conversion of GSH into GSSG is accelerated as a result of excessive hydrogen peroxide generated in the ELF by extracellular glutathione peroxidase. Secondly, the efflux of GSSG from the lung cells is increased because of intracellular oxidative stress. Lung cells have many redox regulating enzymes and thiol containing proteins such as thioredoxins or peroxiredoxins that affect the intracellular GSSG/GSH balance.28,29,30 When the level of intracellular GSSG increases, the export might be accelerated by adenosine triphosphate binding cassette transporters such as multidrug resistant associated protein I (MRP I).31 Thirdly, extracellular GSSG catabolism might be impaired due to the attenuation of membrane bound γ‐glutamyl transpeptidase activity.32 Fourthly, protein reactive thiols, which react with GSSG to release GSH, might be reduced in ELF leading to protein mixed disulfide synthesis.33 Taken together, it is likely that excessive oxidative stress in the lung is causally related to the high level of GSSG in BAL fluid.

Sampling of the ELF by BAL is a common means of studying proteins and investigating their changes in lung diseases. Because of the lack of an appropriate marker for the dilution of lavage fluids (to correct for variable recovery of epithelial lining fluid34), we decided not to normalise the data to albumin or urea. Instead, the data were expressed as the concentrations in the lavaged fluid as in our previous studies.7,8 Despite the difference in the recovery rate of lavage fluid, the level of albumin in the BAL fluid did not differ between the groups (table 2). However, whether the variable rate of recovery may affect the results of comparisons between the groups cannot be determined.

The method and period of storage are also important for evaluating the oxidative status. We used frozen/preserved BAL fluid samples for the assays. Small aliquots of cell free supernatant of BAL fluid were made upon harvest and stored at −70°C to avoid repeated freezing and thawing. It is difficult to directly validate the stability of BAL fluid stored for long periods, but we did not find a significant correlation between storage periods (1–11 years) and the values for each assay for older current smokers (for carbonylated albumin, n = 40, p = 0.73; for GSSG, n = 40, p = 0.65). These results imply that markers of oxidative status such as GSSG and carbonylated albumin in BAL fluid are not directly affected by long term storage at −70°C.

This study clearly shows that the effects of smoking on the extracellular redox system differ with age between recent and long term smokers. It should be noted that older smokers are exposed to cigarette smoke over the years while concurrently ageing. Following smoking, the content of glutathione and the ratio of GSH to total glutathione in the whole lung are significantly lower in senescence accelerated mice than in senescence resistant mice.35 In humans, long term smoking leads to age related decreases in antioxidant activity in alveolar macrophages.36 We also recently reported a decrease with age in surfactant proteins A and D in the BAL fluid of long term smokers compared with age matched non‐smokers, whereas such differences were not observed among young subjects.7 Increases in several markers of oxidative stress have been reportedly linked to pulmonary diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.14,37,38,39 It is still not clear whether oxidative stress plays a direct role in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or whether there is more oxidative stress as a result of ageing with long term chronic smoking. To address this issue, we first evaluated oxidative stress and glutathione redox status in BAL fluids collected from more than 100 subjects classified by age, smoking status, and the presence of mild emphysema in this study.

Although we did not observe a significant enhancement associated with the presence of emphysema according to CT scans, it should be noted that the severity of emphysema was classified as low and that the distribution was heterogeneous even in the older smokers classified as having emphysema. We cannot therefore rule out the possibility that the protein carbonyls and/or GSSG might be higher in BAL fluid from individuals with more advanced stages of emphysema. Although smoking related diseases are often found in older individuals, it is important to keep in mind that the extracellular antioxidant systems in the lungs of older people have an impaired ability to resist damage from cigarette smoke. Further studies will investigate the functions of GSSG and oxidised proteins in BAL fluid and the potential benefits of antioxidant supplementation for middle aged or elderly smokers.

Abbreviations

BAL - bronchoalveolar lavage

DNP - dinitrophenylhydrazine

ELF - epithelial lining fluid

FEV1 - forced expiratory volume in 1 second

GSH - reduced glutathione

GSSG - glutathione disulfide

Footnotes

This research was supported by the Respiratory Failure Research Group of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan and scientific research grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports of Japan (13470125 to MN and 14570532 to TB).

Competing interests: none declared.

References

- 1.Mudway I S, Kelly F J. Modeling the interactions of ozone with pulmonary epithelial lining fluid antioxidants. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 199814891–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies K J. Protein damage and degradation by oxygen radicals. I. General aspects. J Biol Chem 19872629895–9901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalle‐Donne I, Giustarini D, Colombo R.et al Protein carbonylation in human diseases. Trends Mol Med 20039169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahman I, MacNee W. Lung glutathione and oxidative stress: implications in cigarette smoke‐induced airway disease. Am J Physiol 1999277L1067–L1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantin A M, North S L, Hubbard R C.et al Normal alveolar epithelial lining fluid contains high levels of glutathione. J Appl Physiol 198763152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacNee W, Rahman I. Is oxidative stress central to the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Trends Mol Med 2001755–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betsuyaku T, Kuroki Y, Nagai K.et al Effects of ageing and smoking on SP‐A and SP‐D levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Eur Respir J 200424964–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagai K, Betsuyaku T, Ito Y.et al Decrease of vascular endothelial growth factor in macrophages from long‐term smokers. Eur Respir J 200525626–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshioka A, Betsuyaku T, Nishimura M.et al Excessive neutrophil elastase in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in subclinical emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 19951522127–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berglund E, Birath G, Bjure J.et al Spirometric studies in normal subjects. I. Forced expirograms in subjects between 7 and 70 years of age. Acta Med Scand 1963173185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shacter E, Williams J A, Lim M.et al Differential susceptibility of plasma proteins to oxidative modification: examination by western blot immunoassay. Free Radic Biol Med 199417429–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tietze F. Enzymic method for quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total and oxidized glutathione: applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Anal Biochem 196927502–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altuntas I, Dane S, Gumustekin K. Effects of cigarette smoking on lipid peroxidation. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 20021369–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahman I, van Schadewijk A A, Crowther A J.et al 4‐Hydroxy‐2‐nonenal, a specific lipid peroxidation product, is elevated in lungs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002166490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenz A G, Jorens P G, Meyer B.et al Oxidatively modified proteins in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with ARDS and patients at‐risk for ARDS. Eur Respir J 199913169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenz A G, Costabel U, Maier K L. Oxidized BAL fluid proteins in patients with interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J 19969307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kettle A J, Chan T, Osberg I.et al Myeloperoxidase and protein oxidation in the airways of young children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20041701317–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jana C K, Das N, Sohal R S. Specificity of age‐related carbonylation of plasma proteins in the mouse and rat. Arch Biochem Biophys 2002397433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Himmelfarb J, McMonagle E. Albumin is the major plasma protein target of oxidant stress in uremia. Kidney Int 200160358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pignatelli B, Li C Q, Boffetta P.et al Nitrated and oxidized plasma proteins in smokers and lung cancer patients. Cancer Res 200161778–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi J, Malakowsky C A, Talent J M.et al Identification of oxidized plasma proteins in Alzheimer's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 20022931566–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourdon E, Loreau N, Blache D. Glucose and free radicals impair the antioxidant properties of serum albumin. FASEB J 199913233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain A, Martensson J, Mehta T.et al Ascorbic acid prevents oxidative stress in glutathione‐deficient mice: effects on lung type 2 cell lamellar bodies, lung surfactant, and skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992895093–5097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cross C E, O'Neill C A, Reznick A Z.et al Cigarette smoke oxidation of human plasma constituents. Ann NY Acad Sci 199368672–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly F J, Mudway I, Blomberg A.et al Altered lung antioxidant status in patients with mild asthma. Lancet 1999354482–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dauletbaev N, Viel K, Buhl R.et al Glutathione and glutathione peroxidase in sputum samples of adult patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 20043119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bunnell E, Pacht E R. Oxidized glutathione is increased in the alveolar fluid of patients with the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis 19931481174–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dickinson D A, Forman H J. Cellular glutathione and thiols metabolism. Biochem Pharmacol 2002641019–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmgren A. Antioxidant function of thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. Antioxid Redox Signal 20002811–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kinnula V L. Focus on antioxidant enzymes and antioxidant strategies in smoking related airway diseases. Thorax 200560693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Deen M, de Vries E G, Timens W.et al ATP‐binding cassette (ABC) transporters in normal and pathological lung. Respir Res 2005659–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paolicchi A, Lorenzini E, Perego P.et al Extracellular thiol metabolism in clones of human metastatic melanoma with different gamma‐glutamyl transpeptidase expression: implications for cell response to platinum‐based drugs. Int J Cancer 200297740–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas J A, Poland B, Honzatko R. Protein sulfhydryls and their role in the antioxidant function of protein S‐thiolation. Arch Biochem Biophys 19953191–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcy T W, Merrill W W, Rankin J A.et al Limitations of using urea to quantify epithelial lining fluid recovered by bronchoalveolar lavage. Am Rev Respir Dis 19871351276–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uejima Y, Fukuchi Y, Nagase T.et al Influences of inhaled tobacco smoke on the senescence accelerated mouse (SAM). Eur Respir J 199031029–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kondo T, Tagami S, Yoshioka A.et al Current smoking of elderly men reduces antioxidants in alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994149178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pratico D, Basili S, Vieri M.et al Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with an increase in urinary levels of isoprostane F2alpha‐III, an index of oxidant stress. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 19981581709–1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paredi P, Kharitonov S A, Leak D.et al Exhaled ethane, a marker of lipid peroxidation, is elevated in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000162369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drost E M, Skwarski K M, Sauleda J.et al Oxidative stress and airway inflammation in severe exacerbations of COPD. Thorax 200560293–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]