Abstract

Polyaromatic hydrocarbons are ubiquitous environmental pollutants that are potent mutagens and carcinogens. Researchers have taken advantage of these properties to investigate the mechanisms by which chemicals cause cancer of the skin and other organs. When applied to the skin of mice, several carcinogenic polyaromatic hydrocarbons have also been shown to interact with the immune system, stimulating immune responses and resulting in the development of antigen specific T-cell mediated immunity. Development of cell-mediated immunity is strain specific and is governed by Ah receptor genes and by genes located within the major histocompatibility complex. CD8+ T-cells are effector cells in the response, whereas CD4+ T-cells down-regulate immunity. Development of an immune response appears to have a protective effect since strains of mice that develop a cell-mediated immune response to carcinogenic polyaromatic hydrocarbons are less likely to develop tumors when subjected to a polyaromatic hydrocarbon skin carcinogenesis protocol than mice that fail to develop an immune response. With respect to innate immunity, TLR4 deficient C3H/HeJ mice are more susceptible to polyaromatic hydrogen skin tumorigenesis than C3H/HeN mice in which TLR4 is normal. These findings support the hypothesis that immune responses, through their interactions with chemical carcinogens, play an active role in the prevention of chemical skin carcinogenesis during the earliest stages. Efforts to augment immune responses to the chemicals that cause tumors may be a productive approach to the prevention of tumors caused by these agents.

Keywords: polyaromatic hydrocarbon, contact hypersensitivity, skin carcinogenesis, dimethylbenz(a)anthracene, benzo(a)pyrene, immunotoxicology

The polyaromatic hydrocarbons benzo(a)pyrene [B(a)P]1 and dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA) are potent mutagens and carcinogens when applied to the skin. These chemicals are often employed to investigate the mechanisms by which xenobiotics cause cancer. A single application of DMBA or B(a)P results in the formation of stable adducts with the DNA of target cells, leading to mutations in the H-ras oncogene. Repeated exposure of the carcinogen treated skin to tumor promoters such as 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate (TPA), benzoyl peroxide or mezerin produces epigenetic changes in the H-ras mutant cells that convert them into premalignant papillomas. Some of the papillomas then acquire additional mutations that result in their progression to invasive malignancies.

Skin tumors induced by carcinogenic polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) express tumor specific antigens that elicit a cell-mediated immune response. Immunotherapeutic approaches that target these tumor antigens have been effective at producing tumor regression in experimental animal systems, and clinical trials evaluating tumor vaccines in melanoma and other human malignancies have been effective at controlling the growth of these tumors (Morgan et al., 2006). While not to deny its importance, the immune response to antigens expressed by tumors is only one approach with which to limit tumor growth and development. Another strategy would be to target for immunological inactivation the chemicals that cause the tumors. This raises the intriguing possibility that immunological methods that reduce the number of mutant cells before they develop into tumors might be an effective form of immunoprevention. Carcinogenic PAHs have been used to immunize guinea pigs for delayed type hypersensitivity reactions (Old et al., 1963; Pomeranz, 1972; Pomeranz et al., 1980). The resistance of guinea pigs to the carcinogenic activity of these agents has not allowed for an evaluation of the role of the immune system in prevention of tumors by these agents.

Exposure to DMBA suppresses both humoral and cell mediated immunity and persistent immunosuppression caused by it provides an epigenetic mechanism for tumor growth or metastasis (Ward et al., 1986). DMBA produces more extensive B-cell suppression than B(a)P and also alters host resistance to tumors (Ward et al., 1984). Depletion of Langerhan cells during cutaneous carcinogenesis allows activation of suppressor cells capable of inhibiting cellular or humoral antitumor immune responses (Halliday and Muller, 1987). The innate immune system steers the adaptive immune system towards cellular or humoral immune responses. Suganuma et al. (2002) found discrete roles of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6 of innate immune system in tumor promotion and cell transformation. Moore et al. (1999) reported that proinflammatory cytokines were important for de novo carcinogenesis and mice deficient in TNF-α are resistant to skin carcinogenesis. However, constitutive expression of IL-1α in the epidermis of FVB mice rendered them completely resistant to skin carcinogenesis (Murphy et al., 2003).

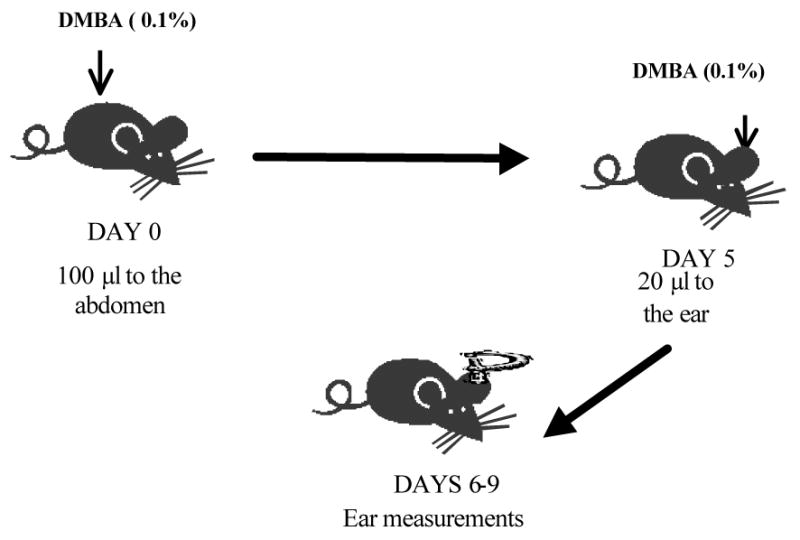

Studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that topical application of DMBA, B(a)P and 3-methylcholanthrene (3-MC) – three carcinogenic polyaromatic hydrocarbons – results in the induction of a contact hypersensitivity response, which is a T-cell-mediated immune response to topically applied haptens (Figure 1) (Klemme et al., 1987; Anderson et al., 1995). The response fulfills all of the requirements of an acquired immune response including antigen specificity and the ability to be adoptively transferred with cell suspensions from draining lymph nodes (Klemme et al., 1987). CD8+ T-cells are the effector cells, whereas CD4+ T-cells play a regulatory role in the response (Anderson et al., 1995; Elmets et al., 2005 (abstr.)).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the role of cell-mediated immunity in PAH-induced skin carcinogenesis.

Metabolic Requirements for Allergic Contact Hypersensitivity to PAHs

Polyaromatic hydrocarbons are hydrophobic substances that undergo enzymatic activation to highly reactive diol, epoxides for many of their biological activities (Conney, 1982) (DiGiovanni, 1995). The rate limiting enzyme in the metabolic pathway is aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase (Gonzalez, 1995). Studies were conducted to determine whether metabolism of topically applied polyaromatic hydrocarbons was required for the development of the cell-mediated immune response. In the first series of experiments, an inhibitor of aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase activity, alpha naphthoflavone, was given to epidermal cell suspensions prior to exposure to DMBA (Anderson et al., 1995). Alpha naphthoflavone inhibited the ability of the epidermal cells to initiate a cell-mediated immune response to DMBA. Alpha naphthoflavone-induced inhibition was not caused by non-specific toxicity because it had no effect on the induction of immune responses to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), a contact allergen that is not metabolized via aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Pretreatment of epidermal cells with alpha naphthoflavone inhibits their ability to initiate contact hypersensitivity responses to DMBA, which is metabolized, but has no effect on contact hypersensitivity to FITC, which is not metabolized.1

| Panel | Alpha Naphthoflavone Pretreatment | Contact Allergen | Change in ear swelling (× 10-3 mm ± SEM) | Percent of positive control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Control1 | − | DMBA | 32 ± 6 | 100 |

| Experimental | + | DMBA | 2 ± 4 | 6 |

| Negative Control | − | DMBA | 3 ± 4 | 9 |

| Positive Control | − | FITC | 43 ± 11 | 100 |

| Experimental | + | FITC | 53 ± 12 | 123 |

| Negative Control | − | FITC | 1 ± 8 | 2 |

C3H/HeN mice were immunized to DMBA by subcutaneously administering an epidermal cell suspension that had been conjugated to DMBA. To assess the necessity for DMBA metabolism for the development of contact hypersensitivity, the cell suspension was pretreated with alpha naphthoflavone prior to DMBA conjugation. To control for non-specific toxicity, separate panels of mice were pretreated with alpha naphthoflavone and then conjugated with FITC, which was not metabolized by aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase.

The initiation of cell-mediated immune responses to topically applied compounds requires that dendritic cells located within the skin present antigens to T-lymphocytes (Sullivan et al., 1986). The XS52 Langerhans cell-like dendritic cell line was therefore evaluated for its ability to metabolize carcinogenic polyaromatic hydrocarbons. The cell line was incubated with [3H]-benzo(a)pyrene [B(a)P]. Supernatants and cell extracts were found to display increased levels of diol, quinone and phenol metabolites, indicating that dendritic cells are capable of metabolizing polyaromatic hydrocarbons, providing strong evidence that metabolism is necessary for the development of cell-mediated immune responses to polyaromatic hydrocarbons.

Strain Variation to the Development of Cell-Mediated Immunity to PAHs

The Ah receptor locus encodes for an intracellular receptor that translocates to the nucleus when PAHs bind to that receptor. This step increases expression of enzymes that metabolize PAHs to diol, epoxides – the ultimate mutagens and carcinogens (Conney, 1982; Gonzalez, 1995). Studies in murine models have shown that the activity of aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase is controlled by two alleles at the Ah receptor locus (Conney, 1982; Gonzalez, 1995). Animals that are homozygous for the b allele metabolize PAHs well, and are much more likely to develop mutations and tumors in response to topical application of these agents than animal that express the d allele. (Conney, 1982).

Experiments were conducted to determine whether strains of mice differed in their capacity to develop contact hypersensitivity to DMBA. Strains of mice that were homozygous for the d allele (strains that are inefficient at metabolizing PAHs) uniformly failed to develop DMBA contact hypersensitivity (Anderson et al., 1995). Some strains that were homozygous for the b allele developed contact hypersensitivity to DMBA, but this was not universally the case, suggesting that other genetic factors were involved in the control of contact hypersensitivity to DMBA (Elmets et al., 1998). To further investigate the genetic component responsible for induction of cutaneous cell-mediated immune responses to PAH, strains of congenic mice that differed only at the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) were tested for their ability to develop this type of reaction. Those studies indicated that, in addition to the Ah receptor locus, proteins encoded by genes within the major histocompatibility locus also participated in the induction of this type of immune response (Elmets et al., 1998). Mice that possessed the H-2k and closely related H-2a loci had significantly greater contact hypersensitivity responses than mice with non-H-2k or non-H-2a loci. This was observed for mice with three different genetic backgrounds (A strain, C57BL/10 and C3H). In each case, cutaneous cell-mediated immunity to DMBA was significantly greater in mice with H-2k and H-2a than in other MHC genes.

To further test the hypothesis that cell-mediated immunity was controlled by polymorphisms in both MHC and Ah receptor loci, F1 hybrids from C57BL/6 (MHC permissive, Ah receptor resistant) and AKR (MHC resistant, Ah receptor permissive) were evaluated for their ability to mount a DMBA contact hypersensitivity response. As expected neither C57BL/6 nor AKR mice developed a significant cell-mediated immune response to DMBA, whereas C57BL/6 × AKR (MHC permissive, Ah receptor permissive) were able to do so (Table 2). Thus, polymorphisms in the Ah receptor locus and in the MHC loci determine the magnitude of the cutaneous cell-mediated immune response to PAHs.

Table 2.

DMBA Contact Hypersensitivity in AKR, C57BL/6 and F1 Hybrids1

| Strain | MHC Haplotype | Ah Receptor Haplotype | Net Increase in Ear Swelling (×10-2 mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AKR | H-2k (Permissive) | AhRb (Non-Permissive) | -0.4 |

| C57BL/6 | H-2b (Non-permissive) | AhRd (Permissive) | 0.1 |

| AKR × C57BL/6 | H-2k × H-2b (Permissive) | AhRb × AhRd (Permissive) | 5.6 |

AKR, C57BL/6 and AKR × C57BL/6 F1 hybrids were sensitized and ear challenged to DMBA employing the protocol described in Figure 1.

MHC influences on polyaromatic hydrocarbon skin tumorigenesis

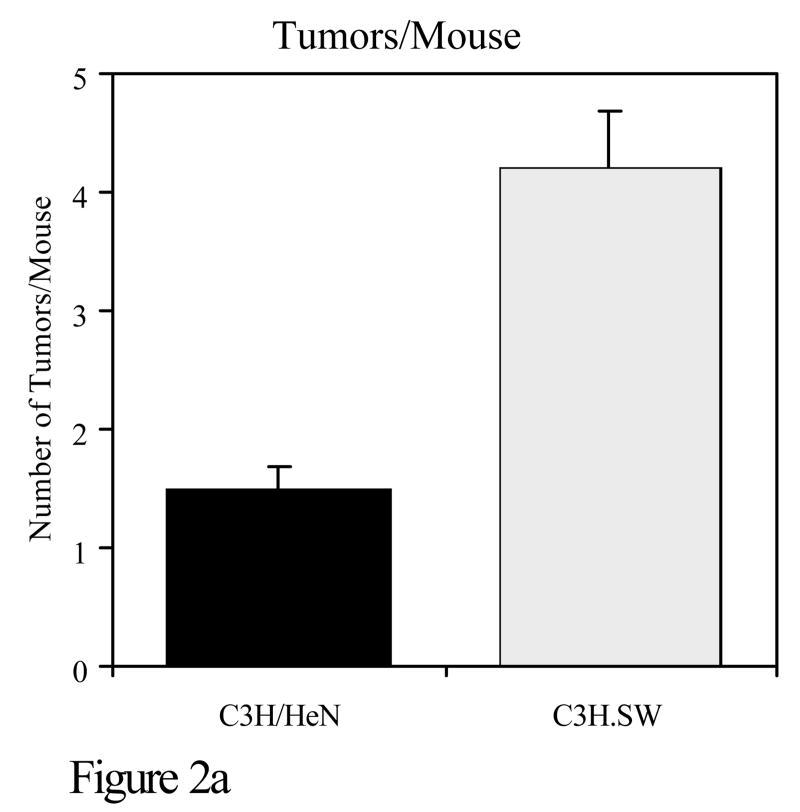

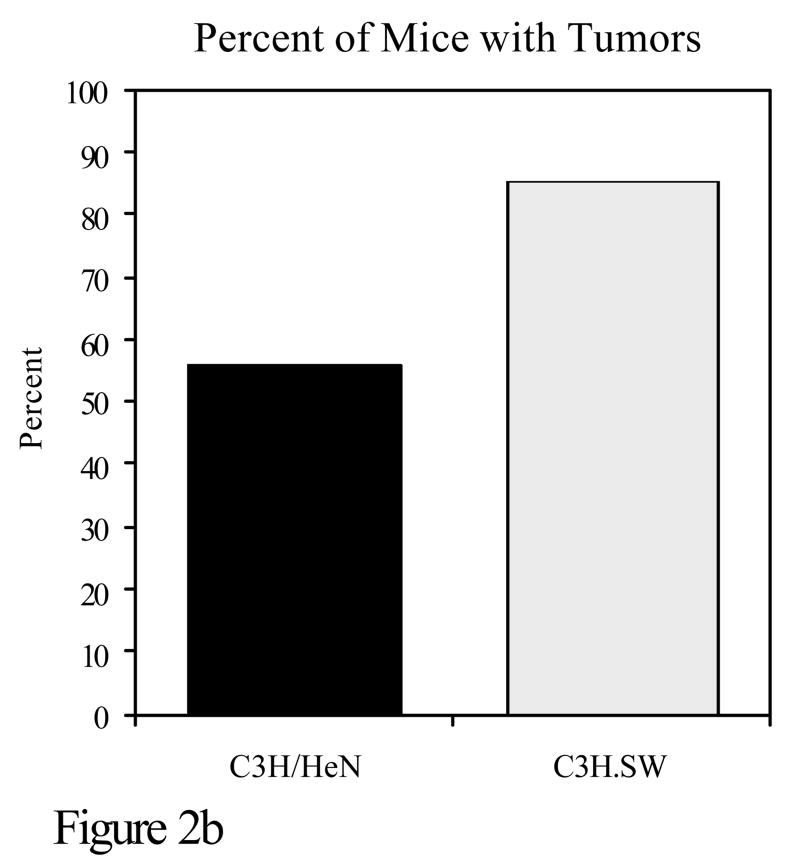

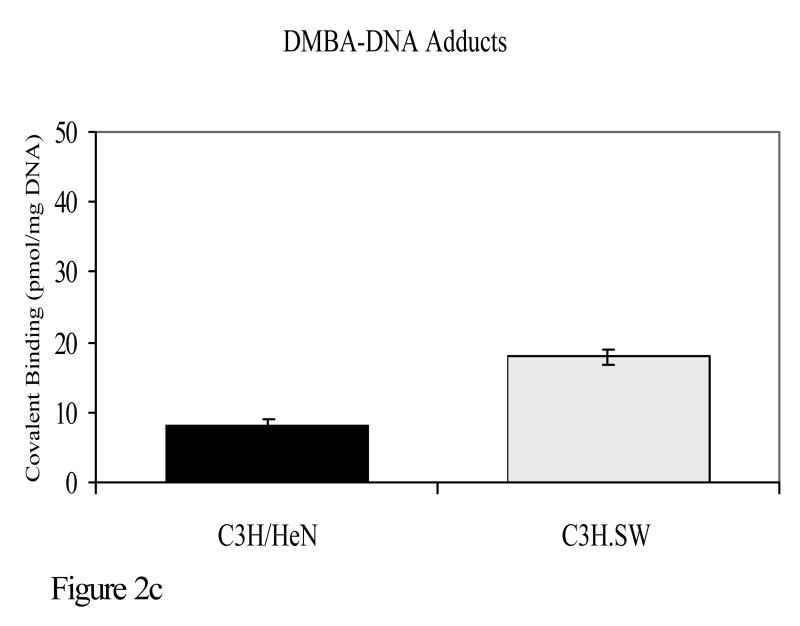

Experiments were also conducted to determine whether susceptibility to the development of tumors when polyaromatic hydrocarbons are applied to the skin coincides with polymorphisms in the major histocompatibility complex. C3H/HeN mice were compared with C3H.SW mice for PAH mutagenesis and tumorigenesis. The only known genetic difference between these two strains is at the murine major histocompatibility complex. C3H/HeN mice are H-2k whereas C3H.SW mice are H-2s at the murine MHC. C3H/HeN mice develop a strong cutaneous cell-mediated immune response to DMBA, whereas C3H.SW mice have a negligible response to that compound. Following topical application of DMBA, C3H/HeN mice had significantly fewer DMBA-DNA adducts than C3H.SW mice. It should be noted that there is a close correlation between adduct formation and mutations caused by PAHs. In experiments in which these same two strains were subjected to a DMBA initiation, TPA promotion skin tumorigenesis protocol, C3H.SW mice developed significantly more skin tumors than C3H/HeN mice (Figure 2)(Elmets et al., 1998).

Figure 2.

C3H/HeN or C3H.SW mice were subjected to a skin tumorigenesis protocol in which DMBA was the initiator. Two weeks later, animals were treated with TPA on the site that had been treated earlier with DMBA. Animals were then assessed weekly for skin tumor development. The results reflect the number of tumors/mouse (panel a) and the percent of mice with tumors (panel b) at 25 weeks. p<0.01 in both panels a and b. c. The skin of C3H/HeN or C3H.SW mice was painted with [H3]-DMBA. Ten days later, the skin was removed and the covalent binding of [H3]-DMBA to DNA was assessed. The results reflect the covalent binding of [H3]-DMBA to DNA (panel c). p< 0.01 in panel c.

TLR4 and polyaromatic hydrocarbon skin tumorigenesis

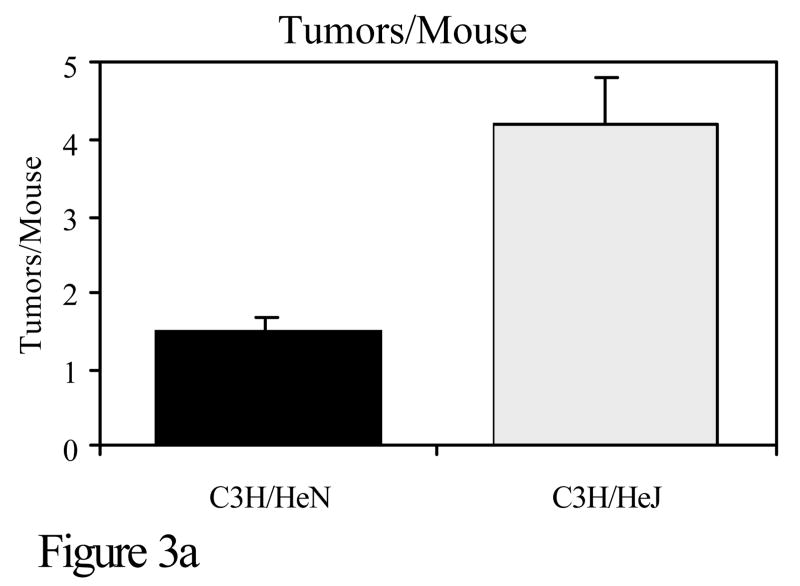

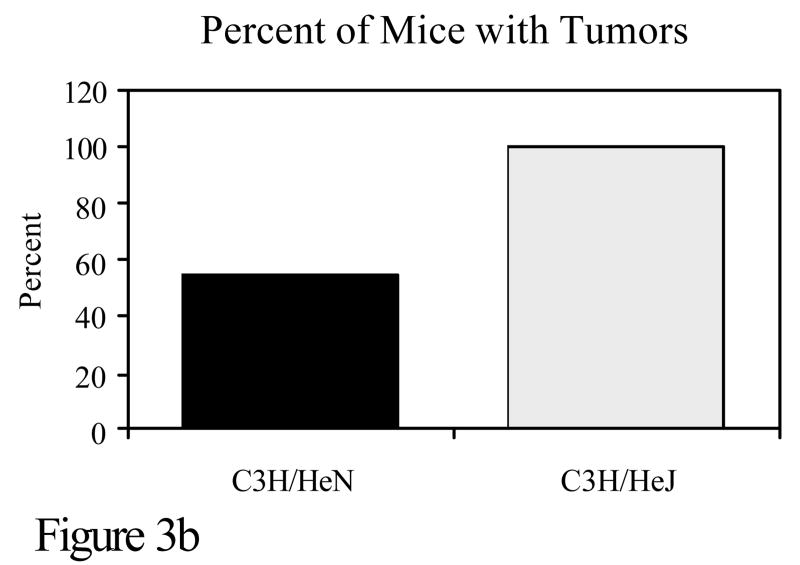

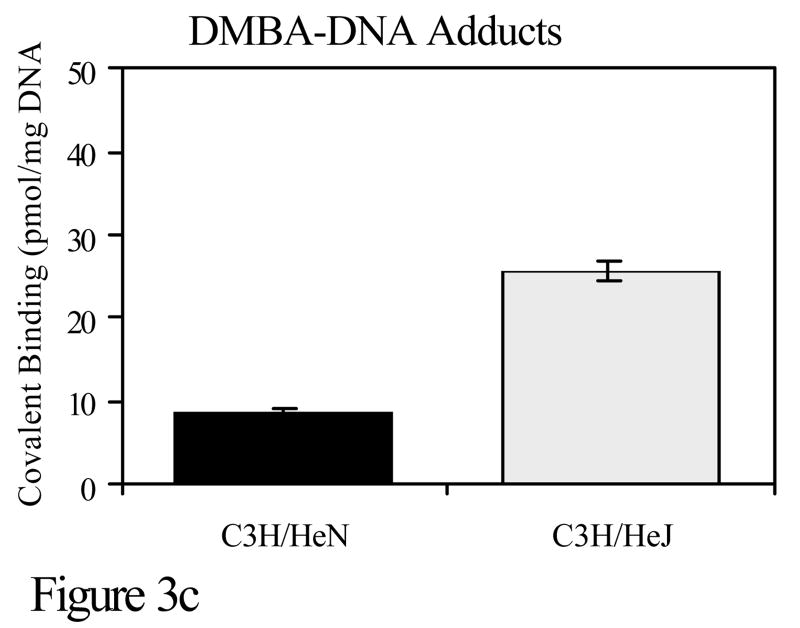

Toll like receptor 4 (TLR4) is a receptor on the surface of cells, which activates the innate immune response. It is through TLR4 that bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) initiates a signaling cascade that results in NF-κB and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation (Takeda et al., 2003). This results in increased transcription number of other genes including the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α. C3H/HeJ mice have a mutation in TLR4 which greatly reduces the function of the TLR4 receptor. The only known difference between C3H/HeN and C3H/HeJ mice is at that site. To investigate the role of TLR4 in DMBA cutaneous mutagenesis and carcinogenesis, C3H/HeN and C3H/HeJ mice were compared for mutations and tumor development. Although little difference was noted in the development of cell-mediated immunity to PAHs, there was a marked disparity in the number of DMBA-DNA adducts and in skin tumorigenesis when mice were subjected to a DMBA initiation, TPA promotion protocol. The skin of C3H/HeN mice contained significantly fewer DMBA-DNA adducts and developed significantly fewer skin tumors than C3H/HeJ mice (Figure 3). Thus, the TLR4 locus represents another immunogenetic locus that confers resistance to PAH-induced tumorigenesis (Elmets et al., 1992).

Figure 3.

C3H/HeN or C3H/HeJ mice were subjected to a skin tumorigenesis protocol in which DMBA was the initiator. Two weeks later, animals were treated with TPA on the site that had been treated earlier with DMBA. Animals were then assessed weekly for skin tumor development. The results reflect the number of tumors/mouse (panel a) and the percent of mice with tumors (panel b) at 25 weeks. p<0.01 in both panels a and b. c. The skin of C3H/HeN or C3H/HeJ mice was painted with [H3]-DMBA. Ten days later, the skin was removed and the covalent binding of [H3]-DMBA to DNA was assessed. The results reflect the covalent binding of [H3]-DMBA to DNA (panel c). p < 0.01 in panel c.

Conclusions

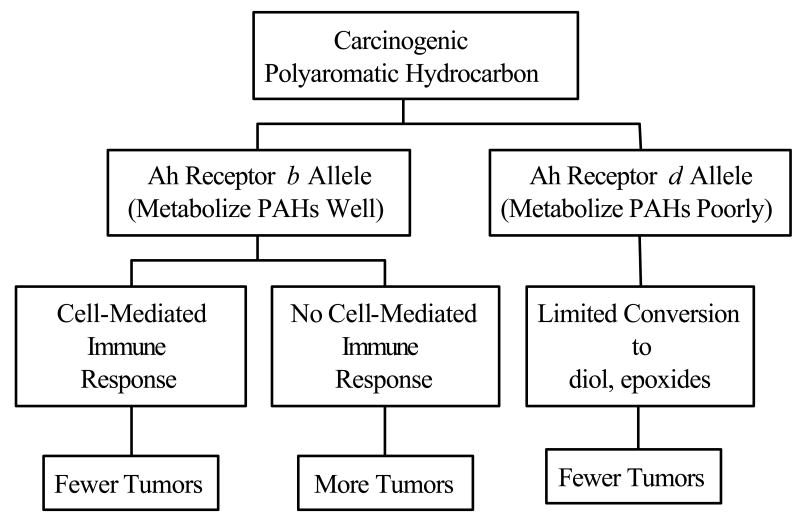

There is a wealth of information indicating that the immune system plays a very important role in suppressing the growth of PAH-induced tumors once they have already developed. These tumors express tumor antigens to which a T-cell-mediated immune response develops. Vaccination against these tumor antigens has been proven to protect animals against the growth of tumors which express these same antigens. There has been little information on the participation of the innate and acquired immune response at times prior to tumor development. Immune responses at this stage could have a significant impact on the ultimate mutagenicity and carcinogenicity of these compounds and could represent an excellent target for prevention. The observation that there is strain variation in the develop immune responses to the carcinogenic polyaromatic hydrocarbon DMBA when it is applied to the skin as well as the demonstration that strains of mice that develop an immune response are resistant to DMBA tumorigenesis is consistent with the hypothesis that PAHs activate antigen specific T-cells that confer a protective effect on individuals. The mechanism for this protective effect could be due to the ability of activated T-cells to identify keratinocytes containing DMBA-DNA adducts and eliminate them at a very early stage in the tumorigenesis pathway. The method in which these immunoprotective mechanisms might be operative is shown in Figure 4. The lack of an effective innate immune response through the TLR4 pathway could also render individuals more susceptible to tumor development.

Figure 4.

Proposed mechanism for the immunoprotective effect of antigen specific T-cell immunity to carcinogenic polyaromatic hydrocarbons.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants P30-AR050948, P30 CA013148, R01-AI50150, R01-AR46256 and VA Merit Award 18-103-02.

Footnotes

| Abbreviations: | |

| 3-MC | 3-methylcholanthrene |

| B(a)P | benzo(a)pyrene |

| DMBA | dimethylbenz(a)anthracene |

| FITC | fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| MHC | major histocompatibility complex |

| PAH(s) | polyaromatic hydrocarbon(s) |

| TLR4 | toll like receptor-4 |

| TPA | 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate |

Disclosures: All authors concur with the submission and have no financial conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson C, Hehr A, Robbins R, Hasan R, Athar M, Mukhtar H, Elmets CA. Metabolic requirements for induction of contact hypersensitivity to immunotoxic polyaromatic hydrocarbons. J Immunol. 1995;155:3530–3537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conney AH. Induction of microsomal enzymes by foreign chemicals and carcinogenesis by polyaromatic hydrocarbons. Cancer Res. 1982;42:4875–4917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiovanni J. Genetic factors controlling responsiveness to skin tumor promotion in mice. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1995;391:195–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmets C, Athar M, Tubesing K, Rothaupt D, Xu H, Mukhtar H. Susceptibility to the Biological Effects of Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons Is Influenced by Genes of the Major Histocompatibility Complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14915–14919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmets CA, Yusuf N, Katiyar SK, Xu H. Antagonistic roles of 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA)-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in DMBA cutaneous carcinogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:A22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3059. abstr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmets CA, Zaidi SI, Bickers DR, Mukhtar H. Immunogenetic influences on the initiation stage of the cutaneous chemical carcinogenesis pathway. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6106–6109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez F. Role of cytochrome P450 1A1 in skin cancer. In: Mukhtar H, editor. Skin Cancer: Mechanisms and Human Relevance. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1995. pp. 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday GM, Muller HK. Sensitization through carcinogen-induced Langerhan cell-deficient skin activates specific long lived suppressor cells for both cellular and humoral immunity. Cell Immunol. 1987;109:206–221. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(87)90305-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemme J, Mukhtar H, Elmets C. Induction of contact hypersensitivity to dimethylbenz[a]anthracene and benzo[a]pyrene in C3H/HeN mice. Cancer Res. 1987;47:6074–6078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RJ, Owens DM, Stamp G, Arnott C, Burke F, East N, Holdsworth H, Turner L, Rollins B, Pasparakis M, Kollias G, Balkwill F. Mice deficient in tumor necrosis factor-alpha are resistant to skin carcinogenesis. Nat Med. 1999;5:828–831. doi: 10.1038/10552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Hughes MS, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Royal RE, Topalian SL, Kammula US, Restifo NP, Zheng Z, Nahvi A, deVries CR, Rogers-Freezer LJ, Mavroukakis SA, Rosenberg SA. Cancer Regression in Patients After Transfer of Genetically Engineered Lymphocytes. Science. 2006;314:126–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1129003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JE, Morales RE, Scott J, Kupper TS. Il-1 alpha, innate immunity, and skin carcinogenesis: the effect of constitutive expression of IL-1 alpha in epidermis on chemical carcinogenesis. J Immunol. 2003;170:5697–5703. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Old L, Benacerraf B, Carswell E. Contact reactivity to carcinogenic polycyclic hydrocarbons. Nature. 1963;198:1215. doi: 10.1038/1981215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeranz J. Preliminary studies of tolerance to contact sensitization in carcinogen-fed guinea pigs. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1972;48:1513–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeranz J, Carney J, Alarif A. The induction of immunologic tolerance in guinea pigs infused with dimethylbenz[a]anthracene. J Invest Dermatol. 1980;75:488–490. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12524261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suganama M, Okabe S, Kurusu M, Iida N, Ohshima S, Saeki Y, Kishimoto T, Fujiki H. Discrete roles of cytokines, TNF-alpha, IL-1, IL-6 in tumor promotion and cell transformation. Int J Oncol. 2002;20:131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S, Bergstresser PR, Tigelaar RE, Streilein JW. Induction and regulation of contact hypersensitivity by resident bone marrow-derived, dendritic epidermal cells: Langerhans cells and Thy-1+ epidermal cells. J Immunol. 1986;137:2460–2467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annual Review of Immunology. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward EC, Murray MJ, Lauer LD, House RV, Irons R, Dean JH. Immunosuppression following 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene exposure in B6C3F1mice 1 Effects on humoral immunity and host resistance. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1984;75:299–308. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(84)90212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward EC, Murray MJ, Lauer LD, House RV, Dean JH. Persistent suppression of humoral and cell mediated immunity in mice mice following exposure to the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene. Int J Pharmacol. 1986;8:13–22. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(86)90068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]