Abstract

An array of highly structured domains that function as metabolite-responsive genetic switches has been found to reside within noncoding regions of certain bacterial mRNAs. In response to intracellular fluctuations of their target metabolite ligands, these RNA elements exert control over transcription termination or translation initiation. However, for a particular RNA class within the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the glmS gene, binding of glucosamine-6-phosphate stimulates autocatalytic site-specific cleavage near the 5′ of the transcript in vitro, resulting in products with 2′–3′ cyclic phosphate and 5′ hydroxyl termini. The sequence corresponding to this unique natural ribozyme has been subjected to biochemical and structural scrutiny; however, the mechanism by which self-cleavage imparts control over gene expression has yet to be examined. We demonstrate herein that metabolite-induced self-cleavage specifically targets the downstream transcript for intracellular degradation. This degradation pathway relies on action of RNase J1, a widespread ribonuclease that has been proposed to be a functional homolog to the well-studied Escherichia coli RNase E protein. Whereas RNase E only poorly degrades RNA transcripts containing a 5′ hydroxyl group, RNase J1 specifically degrades such transcripts in vivo. These findings elucidate key features of the mechanism for genetic control by a natural ribozyme and suggest that there may be fundamental biochemical differences in RNA degradation machinery between E. coli and other bacteria.

[Keywords: Riboswitch, ribozyme, RNase J1, Bacillus subtilis, glucosamine-6-phosphate, RNA sensor, mRNA stability]

Microbes use a diverse assortment of cis-acting regulatory RNA elements, which are almost exclusively located within the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the gene(s) that they regulate. They have been demonstrated to function as sensors for RNA-binding proteins, unrelated RNAs, small molecule metabolites, or specific metal ions (for review, see Winkler 2005; Cromie et al. 2006; Dann et al. 2007). Cis-acting regulatory RNAs that directly respond to intracellular metabolites in order to control expression of downstream genes are commonly referred to as riboswitches (Winkler and Breaker 2005; Gilbert and Batey 2006; Schwalbe et al. 2007). For these RNAs, binding of the correct ligand stabilizes conformational changes within the UTR that in turn dictate the availability of nucleotides required for regulation of downstream gene expression. As a reflection of their overall importance to microbial genetic circuitry, a minimum of 4.1% of the Bacillus subtilis genome is predicted to be controlled by cis-acting regulatory RNAs (Irnov et al. 2006).

Riboswitches are typically comprised of two portions: a ligand-binding region referred to as the aptamer domain, and a downstream portion that includes nucleotides directly involved in genetic control. Although most metabolite-sensing RNAs inhibit downstream gene expression once the aptamer domain adopts a ligand-bound conformation, some exhibit ligand-induced gene activation (Mandal and Breaker 2004). Binding of the appropriate ligand is typically harnessed for regulating formation of a transcription terminator helix or structural elements near the ribosome-binding site (RBS) that affect translation initiation. There is considerable precedence for control of transcription terminator formation (transcription attenuation) by regulatory RNAs (Landick and Yanofsky 1987). Additionally, there are numerous examples of bacterial RNA elements that regulate translation initiation. However, the discovery of a unique RNA element located within the 5′ leader region of the B. subtilis glmS gene (Fig. 1A), which encodes for glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P) synthase, led to the proposal of an entirely different mechanistic strategy (Barrick et al. 2004; Winkler et al. 2004).

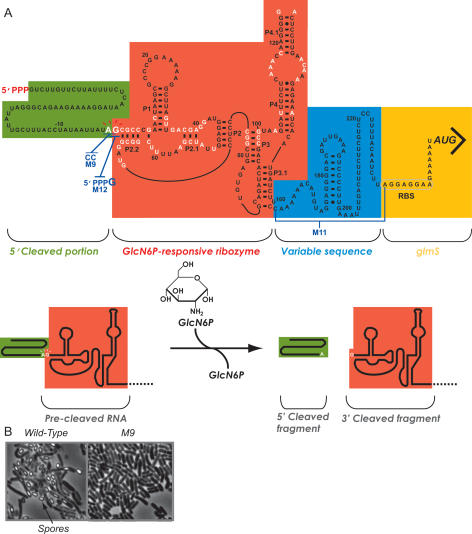

Figure 1.

The B. subtilis 5′ UTR contains a GlcN6P-sensing ribozyme. (A) The sequence of the B. subtilis glmS 5′ UTR is shown. Positions that exhibit >90% conservation are indicated in white (Griffiths-Jones et al. 2005; data not shown). This RNA element has been demonstrated previously to site-specifically cleave in vitro in response to GlcN6P (Winkler et al. 2004). Nucleotides are numbered relative to the site of self-cleavage, with the first nucleotide of the downstream cleavage product corresponding to +1. The green-shaded region denotes the portion of the sequence that is released upon self-cleavage by the ribozyme. The red-shaded region denotes the region corresponding to the GlcN6P-sensing ribozyme (Winkler et al. 2004). The GlcN6P-induced self-cleavage reaction is depicted in the bottom cartoon. The blue-shaded region denotes the nucleotide stretch located between the ribozyme and the downstream coding segment, which is variable between UTRs that contain the glmS ribozyme. Yellow shading denotes the downstream glmS RBS leading into the coding region. (B) A strain containing the M9 mutation (shown in A) (Winkler et al. 2004) within the endogenous glmS 5′ UTR was assayed for its ability to form spores, a developmental program that is likely to require proper coordination of amino sugar pools. B. subtilis strains were induced into sporulation by the resuspension method as described elsewhere (Sterlini and Mandelstam 1969; Nicholson and Setlow 1990). Wild-type B. subtilis cells were capable of sporulation in contrast to M9, which exhibited a loss in spore formation.

The glmS regulatory RNA was discovered through a bioinformatics-based search for sequence conservation within bacterial intergenic regions, an experimental approach that has also led to the discovery of several different proven metabolite-sensing riboswitches (Barrick et al. 2004; Mandal et al. 2004; Corbino et al. 2005; Dann et al. 2007; Roth et al. 2007; Weinberg et al. 2007). Many of the candidate cis-acting regulatory RNAs that emerged from these studies contained sequence elements required for transcription attenuation or control of translation initiation. The glmS RNA appeared to lack these features; therefore, it was not immediately obvious how it would offer control over gene expression. However, in vitro characterization of the glmS UTR revealed that GlcN6P directly associated with the RNA, adding it to the list of known metabolite-sensing riboswitches (Winkler et al. 2004). Surprisingly, GlcN6P binding was found to stimulate site-specific self-cleavage near the 5′ end of the transcript, demonstrating that the RNA is a metabolite-responsive ribozyme (Fig. 1A). Subsequent structural analyses have revealed the three-dimensional architecture of the glmS ribozyme in metabolite-bound and unbound conformations and suggested structural features that are likely to participate in promoting self-cleavage (Klein and Ferre-D’Amare 2006; Cochrane et al. 2007; Klein et al. 2007). These and other biochemical analyses (Hampel and Tinsley 2006; Roth et al. 2006; Tinsley et al. 2007) have revealed that ligand-induced cleavage does not correlate with dramatic structural rearrangements and therefore the glmS ribozyme is preorganized for ligand binding. The latter observations agree well with growing biochemical evidence suggesting that GlcN6P functions as a cofactor for the phosphodiester cleavage reaction (McCarthy et al. 2005; Cochrane et al. 2007).

Other autolytic ribozymes are required for processing of viral or viroid RNA genomes; the glmS ribozyme is therefore unique for its catalytic dependency on GlcN6P and for its presumed role in microbial gene control. Despite rapid improvements in understanding the mechanism of GlcN6P-induced self-cleavage in vitro, the correlation between cleavage and genetic control has not been studied. Furthermore, this relationship is not intuitively obvious. There are no candidate transcription terminators within the glmS 5′ UTR, and the RBS is 235 nucleotides (nt) downstream from the site of self-cleavage. Adding further intrigue, GlcN6P-stimulated cleavage of the glmS 5′ UTR has been shown to produce RNA products with a 2′–3′ cyclic phosphate and a 5′ hydroxyl (Winkler et al. 2004; Klein et al. 2007), similar to other small self-cleaving ribozymes (Fedor and Williamson 2005). Studies of mRNA turnover in Escherichia coli suggest that transcripts containing a 5′ hydroxyl are actually poor substrates for degradation by the RNase E-dependent degradosome complex (Carpousis 2002; Celesnik et al. 2007). Specifically, RNase E, which fulfills a global role in E. coli mRNA turnover, has been demonstrated to be a 5′-end-dependent endoribonuclease that exhibits greatest affinity for transcripts containing a 5′ monophosphate and decreasing affinity for transcripts containing diphosphate, triphosphate, or hydroxyl groups at the 5′ terminus (Mackie 1998; Jiang and Belasco 2004; Celesnik et al. 2007). Based on these observations, one would predict that self-cleavage by the glmS ribozyme would lead to stabilization rather than destabilization of the overall transcript, in contrast with the GlcN6P-responsive feedback repression model that has been proposed for the glmS ribozyme (Winkler et al. 2004). For all of these reasons, we chose to investigate the relationship between ribozyme self-cleavage and glmS expression and to directly test whether molecular identity at the 5′ terminus is an important feature of this mechanism.

Results

The glmS UTR responds to fluctuations in intracellular GlcN6P

As a preliminary test of the importance of the glmS ribozyme in maintaining cell wall homeostasis, the glmS ribozyme was mutated such that it was incapable of self-cleavage (“M9”) (Fig. 1A). This site-directed mutation was not accompanied by any other genomic alterations. In contrast to a wild-type strain, the M9 mutant strain was incapable of sporulation, demonstrating that disruption of glmS ribozyme function is itself deleterious and that glucosamine pools are likely to be strictly maintained during B. subtilis development (Fig. 1B). This strain also exhibited a defect in biofilm production (data not shown), most likely due to imbalances in glucosamine precursors simultaneously required for synthesis of peptidoglycan and extracellular biofilm polysaccharides.

In order to study the glmS regulatory mechanism in greater detail. B. subtilis strains were engineered to exhibit controllable production of GlcN6P (Fig. 2A). Specifically, the glmS coding region was replaced through allelic exchange with a gene encoding for erythromycin resistance (erm). The upstream ribozyme was not deleted and was therefore transcriptionally fused to erm upon creation of this strain. The glmS coding sequence was instead positioned under control of an isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter on a self-replicating plasmid (pDG148). For some strains, an additional copy of the glmS 5′ UTR was fused to a lacZ reporter gene and ectopically integrated into the genome. These strains were all dependent on addition of IPTG for continued growth, confirming that glmS is an essential gene (Fig. 2B; Kobayashi et al. 2003). Cellular growth ceased ∼2 h after withdrawal of IPTG. This observation corresponded with a significant change in morphology from rod-shaped bacilli to round-shaped entities of variable size, likely to be protoplasts (Fig. 2B). Measurements of glmS transcripts by reverse transcription/quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) demonstrated an approximately sevenfold increase in abundance as extracellular IPTG was raised from 1 μM to 5 mM (data not shown). These data together confirm that the B. subtilis glmS gene is indeed essential for peptidoglycan biosynthesis and that intracellular GlcN6P pools can be manipulated through control of the GlmS enzyme. Furthermore, these data together argue that the glmS regulatory ribozyme is likely to fulfill a critically important role in maintaining cell wall homeostasis.

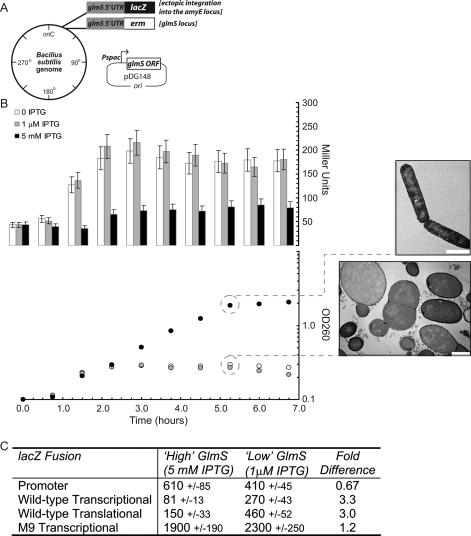

Figure 2.

GlcN6P-responsive regulation in vivo by the B. subtilis glmS ribozyme. (A) B. subtilis strains (all derived from strain BR151; BGSC) containing inducible control of glmS were constructed in the following manner: The glmS coding sequence was placed under an IPTG-inducible promoter on a low-copy plasmid (pDG148; BGSC). The chromosomal glmS coding region was exchanged for an erm cassette, thus creating a transcriptional fusion of erm to the glmS 5′ UTR. Finally, the glmS 5′ UTR was fused to a lacZ reporter (pDG1661; BGSC), and the resulting sequences were integrated into the amyE gene. (B) These cells were cultured in glucose minimal medium, and IPTG was either supplied in excess or was depleted at OD600 = 0.1. The growth of the strains was monitored by measurements of OD600, and samples were withdrawn for analysis by electron microscopy. Samples were withdrawn every 45 min for measurements of β-galactosidase activity. (C) A variety of different glmS 5′ UTR–lacZ fusions were assayed for β-galactosidase activity in strains exhibiting inducible control of GlmS. For these experiments, which were conducted identical to experimentation described in B, cells were harvested for β-galactosidase activity measurements 5 h after OD600 = 0.1.

Post-transcriptional regulation of B. subtilis glmS

In response to a decrease in GlcN6P, B. subtilis strains containing a ribozyme–lacZ fusion exhibited a modest (approximately threefold) but reproducible increase in reporter expression (Fig. 2B; cf. data from cells cultured with 1 μM to those with 5 mM IPTG). This responsiveness of the glmS ribozyme to fluctuations in intracellular GlcN6P agrees well with prior biochemical results that indicated the ribozyme binds directly and selectively to GlcN6P (Winkler et al. 2004; Klein and Ferre- D’Amare 2006; Cochrane et al. 2007). Therefore, these data support the hypothesis that the glmS ribozyme responds to in vivo GlcN6P levels for regulation of downstream gene expression. To delineate whether this regulatory influence is wielded over translation or transcript abundance, different ribozyme–lacZ constructs were examined during conditions of high and low GlcN6P (Fig. 2C). A fusion of lacZ to the glmS promoter region, which was identified through primer-extension mapping of the 5′ terminus (data not shown), exhibited increased expression overall relative to a wild-type ribozyme sequence, suggesting that the ribozyme limits downstream expression. However, the promoter–lacZ fusion lacked GlcN6P responsiveness, indicating that GlcN6P-responsive regulation occurs post-transcription initiation (Fig. 2C). A translational reporter fusion was constructed through in-frame fusion of the glmS N terminus with lacZ. This construct demonstrated approximately threefold responsiveness to GlcN6P, identical to the transcriptional ribozyme–lacZ fusion. That additional GlcN6P-responsive regulation was not observed for the translational fusion relative to the transcriptional fusion argues against metabolite-responsive control over translation initiation. Site-directed mutagenesis of the ribozyme self-cleavage site from 5′-AG-3′ to 5′-CC-3′, referred to as the M9 mutant, has been demonstrated previously to eliminate self-cleavage activity in vitro (Winkler et al. 2004). Structural analyses of glmS ribozymes have revealed that these nucleotides participate in direct hydrogen-bonding interactions to the GlcN6P ligand (Klein and Ferre-D’Amare 2006; Cochrane et al. 2007; Klein et al. 2007), suggesting that mutagenesis of these resides is likely to eliminate the ability of GlcN6P to bind to the ribozyme. Given that the M9 ribozyme is inactive for self-cleavage in vitro, expression of the M9–lacZ fusion would be expected to correspond to the upper expression limit for the dynamic range exhibited by the regulatory ribozyme in vivo. Analysis of the M9–lacZ fusion during low and high GlcN6P demonstrated that, indeed, expression was significantly increased and unresponsive to fluctuations in GlcN6P (Fig. 2C). However, M9–lacZ expression was still approximately eightfold higher than that of the wild-type sequence during conditions of GlcN6P deprivation, conditions when wild-type expression would be expected to be maximally engaged. This observation suggests that either intracellular glucosamine pools are not thoroughly depleted under our experimental conditions or that ribozyme self-cleavage is in part stimulated even in the absence of GlcN6P in vivo. It is also possible that other metabolites bearing structural resemblances to portions of GlcN6P could stimulate ribozyme self-cleavage in vivo.

The glmS ribozyme controls mRNA stability in response to intracellular GlcN6P pools

Ribozyme-containing transcripts were monitored by qPCR in order to directly measure the impact of GlcN6P variations on transcript abundance (Fig. 3A). Ribozyme-containing transcripts increased ∼37-fold in response to GlcN6P depletion, whereas the M9 mutant exhibited almost no change. Similar to the analysis of ribozyme–lacZ reporters, M9 transcripts were found to be substantially higher (∼13-fold) than that of wild-type transcripts during conditions of high GlcN6P (data not shown). It is not immediately clear why measurements of transcript abundance by qPCR revealed a greater fold change upon GlcN6P depletion than with measurements of LacZ expression (e.g., 37-fold vs. threefold, respectively). The amplicons chosen for qPCR analyses consisted of ∼100-nt portions of the overall transcript(s), whereas LacZ expression could only result from full-length, translation-competent mRNAs. One potential explanation therefore is that there are mRNA degradation intermediates that are detected by qPCR analysis but that are not functional lacZ templates. Ribozyme-containing transcripts were further examined by Northern blot analyses via an antisense RNA probe to the glmS UTR (Fig. 3B). These tests revealed that ribozyme-erm transcripts were undetectable during conditions of high GlcN6P. However, GlcN6P depletion led to significant transcript accumulation. In contrast, M9-erm transcripts were highly expressed regardless of GlcN6P levels. To ensure that these results were general for all ribozyme-containing transcripts, we monitored levels of ribozyme–lacZ transcripts, which were also found to be detectable only during low GlcN6P conditions.

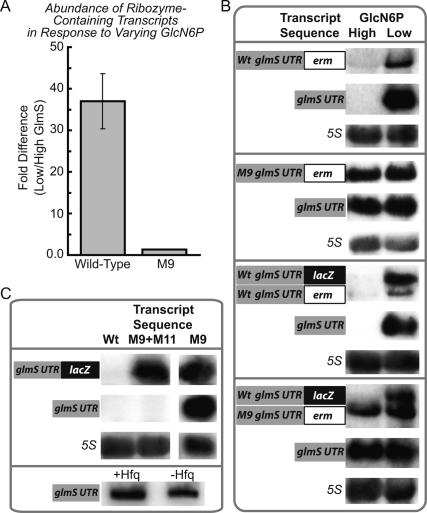

Figure 3.

GlcN6P-induced ribozyme self-cleavage controls intracellular abundance of ribozyme-containing transcripts. (A) qPCR analyses of glmS 5′ UTR regions during conditions of high or low GlmS reveal significant differences in abundances of wild-type transcripts in response to GlmS reduction; however, virtually no change for M9 transcripts occurs under these conditions. The bacterial strains and growth conditions for this experiment, which was performed in triplicate, were identical to those described in Figure 2 (and further described in the Materials and Methods). Specifically, cells were harvested for qPCR measurements 5 h after OD600 = 0.1. (B) Transcripts containing either wild-type or M9 glmS 5′ UTRs were assayed by Northern blot analyses during conditions of high and low GlmS. Antisense RNA probes, which constituted the reverse complementary sequence of the glmS 5′ UTR, were used for detection of ribozyme-containing transcripts. The latter transcripts, which were resolved by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis (see Materials and Methods for further details), were found to accumulate during conditions of GlmS deprivation. An RNA species, roughly the size of the glmS 5′ UTR and resolved by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis (see Materials and Methods), was also found to accumulate during conditions of GlmS deprivation. A representative Northern blot showing simultaneous resolution of these different RNA species within the same gel is shown in the Supplemental Material. (C) Deletion of the 74-nt intervening region between the 3′ end of the ribozyme and the downstream glmS RBS (M11) resulted in the absence of the smaller glmS 5′ UTR species, suggesting that an RNase enzyme endonucleolytically cleaves within this region. The M9 construct was also assayed by Northern blot analyses in a wild-type background strain as well as a strain deleted for Hfq, an RNA-binding protein commonly observed to stabilize small noncoding RNAs. Loss of Hfq appeared to have minimal influence on M9 stability.

Interestingly, in addition to observing correctly sized full-length transcripts, we also noted a smaller RNA species that hybridized well with an antisense probe to the glmS UTR (Fig. 3B,C; Supplemental Material). The length of this RNA species was found to be ∼250 nt, roughly the size of the glmS ribozyme, as estimated by comparing migration distances during electrophoresis against RNA size standards (data not shown). Similar to full-length ribozyme-containing mRNAs, the presence of the isolated glmS UTR RNA was inversely proportional to GlcN6P levels, remaining undetectable during high GlcN6P but becoming abundant during GlcN6P depletion. These observations together suggest that the 5′ UTR becomes physically separated from glmS transcripts for a subpopulation of the ribozyme-containing mRNAs. Furthermore, stability of the ribozyme-containing UTR is controlled identical to the full-length transcripts, in agreement with the hypothesis that regulatory control emanates entirely from the metabolite-sensing ribozyme. We tested whether the well-studied RNA-binding protein Hfq was required for stabilization of the isolated glmS 5′ UTR under conditions that favored the precleaved state (Fig. 3C). Deletion of Hfq, which is required for stabilization of many small trans-acting regulatory RNAs in other bacteria (Storz et al. 2005; Gottesman et al. 2006; Vogel and Papenfort 2006), did not noticeably affect abundance of the glmS UTR species, suggesting that other factors are likely to be required for stabilization of precleaved glmS transcripts.

As highlighted in Figure 1A, there are three distinct regions of the glmS UTR. The most 5′ portion is a short 62mer region predicted to be released upon ribozyme self-cleavage. This is followed by the catalytic ribozyme domain and a highly variable region between the ribozyme and downstream glmS coding sequence (Barrick et al. 2004; Griffiths-Jones et al. 2005; data not shown). To test whether the UTR was released from full-length transcripts as a result of RNase-mediated cleavage within this variable region, a mutant (“M11”) was constructed that was deleted for this portion (Fig. 1A). Indeed, when the M9 ribozyme-inactivating mutation was combined with the M11 deletion mutant, full-length transcripts were observed by Northern blotting, but not the ∼250-nt glmS UTR fragment (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that an unidentified RNase enzyme cleaves within the region between the ribozyme and downstream coding portion for a subpopulation of glmS transcripts. However, the fact that full-length transcripts are still stabilized by the M9 mutation, even in the context of the M11 deletion, suggests that the RNase-mediated release of the UTR is not likely to be a required feature of glmS genetic mechanism.

The widespread ribonuclease, RNase J1, is required for selective degradation of self-cleaved transcripts

Our data demonstrate that self-cleaved glmS transcripts are destabilized relative to their precleaved counterparts. This may be a consequence of active stabilization of precleaved mRNAs by protein factors, active destabilization of the 3′ cleavage product by RNase enzymes, or a combination of both mechanisms. Degradation of bacterial mRNAs has been best studied in E. coli (Kushner 2004; Deutscher 2006; Condon 2007), wherein the endoribonuclease enzyme, RNase E, performs a global role in initiating mRNA decay. It is still unclear what features of mRNA degradation paradigm established for E. coli will be generally upheld by other bacteria given that RNase E does not appear to be present in many species (Condon and Putzer 2002; Even et al. 2005). In organisms that lack RNase E, a counterpart for RNase E activity has not been conclusively identified.

Akin to many Gram-positive bacteria, the B. subtilis genome lacks an RNase E homolog. However, recent data have suggested that an essential ribonuclease, RNase J1, may fulfill the functional requirements of this enzyme (Even et al. 2005). RNase J1 has been reported to be an endoribonuclease that cleaves within the UTRs of tRNA-sensing B. subtilis regulatory RNAs (Even et al. 2005). More recently, it has also been reported to exhibit 5′-to-3′ exoribonuclease activity, an activity previously unobserved for bacteria (Mathy et al. 2007). Other reports have suggested that RNase J1 is required for processing of 16S rRNA and the signal recognition particle RNA component (Britton et al. 2007; Yao et al. 2007). The sum of these reports hints at a broad role for RNase J1 activity in B. subtilis and other microbes.

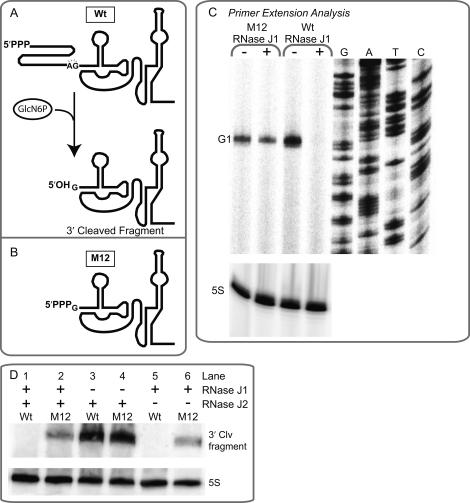

To investigate a role for RNase J1 in glmS regulation, ribozyme-containing transcripts were analyzed in the presence of RNase J1 or after its withdrawal (Fig. 4A). Depletion of RNase J1 led to accumulation of ribozyme-containing transcripts, demonstrating that the enzyme is required for glmS degradation. In agreement with these data, expression of a ribozyme–lacZ fusion increased significantly upon removal of RNase J1 (Fig. 4B). Denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of M9 transcripts revealed the presence of precleaved transcripts during the presence and absence of RNase J1 (Fig. 4C). However, wild-type sequences, which were undetectable in the presence of RNase J1, accumulated in response to RNase J1 depletion, indicating that RNase J1 is specifically required for degradation of the 3′ cleavage product. Notably, the size of these transcripts diminished by ∼60 nt, roughly the same size as the 5′ cleavage fragment that was predicted to be released upon ribozyme self-cleavage (Fig. 1A). These data therefore offer direct evidence for intracellular self-cleavage by the glmS ribozyme and suggest that the 3′ cleavage product is specifically targeted for degradation by RNase J1. Indeed, wild-type transcripts that accumulated during RNase J1 depletion were found to exhibit a 5′ terminus exactly at the site of ribozyme self-cleavage, as ascertained by 5′ primer extension analyses (“G1”) (Fig. 4D). In total, these data indicate that RNase J1 is specifically required for degradation of glmS transcripts in response to ribozyme self-cleavage.

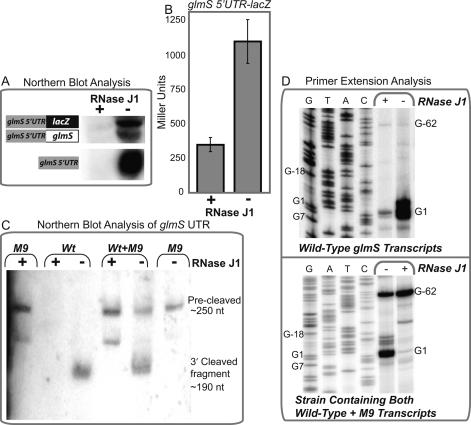

Figure 4.

Degradation of self-cleaved transcripts is dependent on action by RNase J1. (A) Ribozyme-containing transcripts were analyzed by Northern blot analyses using an antisense radiolabeled probe that could hybridize to the glmS 5′ UTR. RNA was extracted from strain GP41 (Jörg Stülke, University of Göttingen, Germany), which exhibits xylose-inducible control of RNase J1. For these experiments, cells were cultured in rich media (2XYT) in the presence or absence of 1.5% xylose to mid-exponential phase, at which point they were harvested for OD600 and experimental assays (β-galactosidase activity assays, RNA extraction). (B) The observation that depletion of RNase J1 led to accumulation of ribozyme-containing transcripts was further supported by measurements of activity for lacZ fusions to the glmS 5′ UTR, which exhibited an increase in expression in response to RNase J1 depletion. (C) Northern blotting of the glmS 5′ UTR when resolved by denaturing 6% PAGE revealed that wild-type transcripts accumulated during RNase J1-deprived conditions. Furthermore, the size of these RNAs was ∼60 nt smaller than that of M9 transcripts, consistent with ribozyme self-cleavage in vivo. (D) Direct support of the latter was obtained through primer extension analyses of transcripts containing the glmS ribozyme. Wild-type transcripts were again found to accumulate in response to withdrawal of RNase J1. However, the site of self-cleavage was found to constitute the 5′ terminus for these transcripts.

Molecular identity at the 5′ terminus is a signal for RNase J1-mediated mRNA degradation

Analyses of RNase E-mediated mRNA decay in E. coli have demonstrated that transcripts containing a 5′ hydroxyl are poorly degraded while those containing a 5′ monophosphate are subjected to rapid turnover (Mackie 1998; Jiang et al. 2000; Tock et al. 2000; Jiang and Belasco 2004; Celesnik et al. 2007). Our data on the mechanism of glmS regulation therefore stand in contrast to features of the E. coli mRNA decay paradigm. We sought to directly investigate whether molecular identity at the 5′ terminus is important for RNase J1-mediated mRNA degradation. To validate that the 3′ cleavage product retains a 5′ hydroxyl group in vivo, we extracted total RNA and found that the 3′ cleavage product could only ligate to an upstream DNA oligonucleotide if the total RNA sample was first phosphorylated by T4 polynucleotide kinase (Supplemental Material). An altered glmS (“M12”) was then constructed such that transcription initiated at the +1 G residue (Figs. 1, 5A,B), which for wild-type ribozyme sequence is rendered the 5′ terminus upon self-cleavage. Therefore, the M12 transcript is identical in sequence to the wild-type 3′ cleavage product. However, the transcripts differ in that M12 RNAs contain a triphosphate at their 5′ terminus, while wild-type transcripts exhibit a 5′ hydroxyl group upon self-cleavage. Strikingly, M12 RNAs accumulated in the presence and absence of RNase J1, in contrast to the specific accumulation of self-cleaved wild-type transcripts upon RNase J1 depletion (Fig. 5A–C). These data suggest that transcripts containing a 5′ hydroxyl can be targeted for degradation by B. subtilis RNase J1.

Figure 5.

Molecular identity at the 5′ terminus of self-cleaved transcripts is important for RNase J1-mediated degradation. (A) A schematic highlighting molecular identity at the 5′ terminus upon ribozyme self-cleavage. Wild-type sequences contain a hydroxyl group at the 5′ terminus after self-cleavage. (B) In contrast, the M12 mutant was created such that transcription initiated at G + 1 (the site of self-cleavage) and therefore contained a triphosphate group at the 5′ terminus (see Materials and Methods for further description). (C) Primer extension analyses of total RNA samples during conditions of replete or depleted RNase J1 revealed that M12 transcripts accumulated regardless of RNase J1 status, whereas wild-type, hydroxyl-terminated transcripts were degraded in an RNase J1-dependent manner. For these experiments, cells were cultured as described in Figure 4 and in Materials and Methods. (D) Depletion of RNase J1 but not RNase J2 led to accumulation of wild-type transcripts. Similarly, M12 transcripts accumulated regardless of the presence or absence of RNase J1 and RNase J2.

In addition to RNase J1, the B. subtilis genome also contains a separate ribonuclease exhibiting high sequence identity (49%) to the RNase J1 protein, which has been renamed RNase J2 (Even et al. 2005). RNase J1 and RNase J2 have been demonstrated to cleave tRNA-sensing RNA elements in vitro at similar locations (Even et al. 2005). The role of RNase J2 in B. subtilis mRNA degradation is unclear, although unlike RNase J1, it is not an essential gene. To investigate the potential role for RNase J2 in glmS regulation, wild-type and M12 transcripts were monitored during the presence and absence of both enzymes (Fig. 5D). M12 transcripts accumulated regardless of the presence or absence of RNase J1 and RNase J2 (Fig. 5D, cf. lanes 2,4,6). However, depletion of only RNase J1 resulted in accumulation of the 3′-cleavage product for wild-type transcripts (Fig. 5D, cf. lanes 1,3,5). These experiments were conducted with strains expressing either wild-type glmS–lacZ or M12–lacZ fusions, but that still also retained the wild-type ribozyme sequence within the endogenous glmS locus. Therefore, the apparent increase in signal intensity for M12 transcripts upon RNase J1 depletion (as shown in Fig. 5D) can be explained by the additive effects of M12 RNAs and accumulation of wild-type self-cleaved ribozymes. In total, these data argue that RNase J2 is not required for regulation of glmS stability by the GlcN6P-sensing ribozyme.

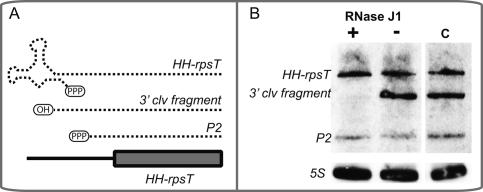

These data together predict that the addition of RNase J1 to E. coli would result in degradation of transcripts containing a 5′ hydroxyl. To test this hypothesis, the hammerhead ribozyme, which also generates products containing 2′,3′ cyclic phosphate and 5′ hydroxyl termini, was fused upstream of the rpsT transcript (Fig. 6A). This construct, which was used previously to demonstrate the longevity of transcripts containing a 5′ hydroxyl in E. coli (Celesnik et al. 2007), also retains a second promoter (P2) upstream of rpsT but downstream from the hammerhead ribozyme. Northern blots reveal the presence of the precleaved transcript, the 3′ cleavage product, and the P2 transcript (Fig. 6B). However, only the 3′ cleavage product is specifically destabilized upon concurrent expression of RNase J1 in E. coli. These data further establish RNase J1 in the molecular recognition and degradation of 5′ hydroxyl-containing transcripts, including those that are unrelated to the glmS ribozyme.

Figure 6.

Degradation of 5′ hydroxyl-containing transcripts in E. coli is dependent on RNase J1. (A) A schematic is shown of the hammerhead-rpsT construct (HH-rpsT) used to generate transcripts with 5′ hydroxyl groups in vivo. Different transcripts produced by this transcriptional unit are shown in dotted lines with the corresponding 5′ phosphorylation state. The full-length mRNA containing a hammerhead ribozyme fused to rpsT (denoted as HH-rpsT; see Materials and Methods) is shown at the top. The 3′ product of the ribozyme self-cleavage in vivo (denoted as 3′ clv fragment) exhibits identical sequence to the endogenous, triphosphorylated rpsT P1 mRNA, except for the presence of a 5′ hydroxyl. P2 denotes the second rpsT mRNA, which is identical to the native rpsT P2 transcripts. The plasmid-encoded rpsT transcripts contain a 19-nt sequence tag within the 3′ UTR of the mRNA, used for hybridization of a radiolabeled probe during Northern blotting (see Materials and Methods). (B) rpsT transcripts were resolved by 6% PAGE and assayed by Northern blot analyses. For these experiments, RNA was extracted from E. coli strain DH5α containing arabinose-inducible RNase J1 and the hammerhead-rpsT construct. These cells were cultured to mid-exponential phase in the presence or absence of 0.2% arabinose. “C” denotes a control experiment with RNA extracted from E. coli strain DH5α containing only the HH-rpsT construct. The 3′ clv fragment is diminished in the presence of RNase J1, while triphosphorylated transcripts (HH-rpsT and P2) remain unaffected.

Discussion

The intracellular stability of mRNAs is intimately linked to gene expression through restriction of the amount of protein produced from individual mRNA templates. Therefore, in addition to genetic strategies that control transcription initiation or translation initiation, mechanisms that determine mRNA stability are essential in establishing intracellular expression levels. There are many factors that can potentially influence mRNA stability (Grunberg-Manago 1999; Condon 2003). For example, the overall degree of translation can affect mRNA stability, presumably through ribosome-mediated protection from RNase enzymes for mRNA transcripts that are heavily translated (Arnold et al. 1998; Braun et al. 1998; Deana and Belasco 2005). The phosphorylation state at the 5′ terminus also significantly influences RNA half-lives (Jiang et al. 2000; Tock et al. 2000; Celesnik et al. 2007). Furthermore, polyadenylation of mRNA 3′ termini can have a significant impact on intracellular stability for a subset of the total mRNA population (Xu and Cohen 1995; Li et al. 1998; Dreyfus and Regnier 2002; Kushner 2004; Joanny et al. 2007). Structural elements proximal to the 5′ or 3′ termini, such as 5′ stem–loops or 3′ intrinsic transcription terminators, can also significantly influence mRNA stability (Belasco et al. 1985; McLaren et al. 1991; Emory et al. 1992; McDowall et al. 1995; Hambraeus et al. 2000; Sharp and Bechhofer 2005). Finally, regulatory protein factors or ribosomal initiation complexes may act to specifically stabilize or destabilize mRNAs (Liu et al. 1995; Glatz et al. 1996; Folichon et al. 2003; Sharp and Bechhofer 2003). It is likely that the sum of many such features, acquired as the result of evolutionary selective pressure, are needed to establish appropriate expression levels. Therefore, mechanisms that alter these parameters can have profound effects on gene expression.

A plethora of bacterial cis-acting regulatory RNAs have been discovered in the past several decades. The majority of these RNA elements exert their regulatory influence over the processes of transcription elongation or translation initiation. Specifically, these RNAs typically offer sensitive control over a transcription terminator helix within the 5′ UTR or structured regions near to or encompassing the RBS. Bioinformatics searches for bacterial regulatory RNAs have uncovered numerous examples where these regulatory elements are either absent or simply difficult to identify. This and other observations suggest that regulatory mechanisms other than transcription attenuation and RBS sequestration may still await detection.

In imagining the potential regulatory strategies used by these heretofore unidentified RNAs, the potential control of mRNA stability via action of cis-acting regulatory RNAs would be predicted to provide an efficient means for affecting gene expression for the reasons outlined in the preceding paragraphs. Indeed, there are established examples of cis-acting regulatory RNAs that specifically interact with RNase enzymes in order to establish expression levels of downstream genes (e.g., Diwa et al. 2000). Also, a variety of trans-acting regulatory RNAs have been identified that are required for specific destabilization of target mRNAs (Storz et al. 2005; Gottesman et al. 2006; Vogel and Papenfort 2006). An accruement of scientific literature in the past few decades has demonstrated that RNAs are capable of the structural sophistication required for performing autocatalytic reactions, such as self-cleavage, an activity that could be conceivably coupled to control of RNA stability. Several classes of self-cleaving RNAs have been intensively studied, including the hammerhead, hepatitis delta virus (HDV), hairpin, and Varkud satellite (VS) ribozymes (Doudna and Cech 2002; Fedor and Williamson 2005). None of these RNAs are used for control of gene expression or respond to metabolic changes through alterations in their catalytic behavior. However, a wide variety of chemical-responsive, self-cleaving ribozymes have been designed through molecular engineering approaches (Breaker 2004), demonstrating proof-in-principle that signal-responsive RNA cleavage should also be considered as a legitimate genetic strategy for biological RNAs. As detailed herein, the latter prediction was confirmed with the discovery of the glmS ribozyme in B. subtilis and other Gram-positive bacteria, which was demonstrated to site-specifically self-cleave in vitro in response to association with the glmS metabolic product, GlcN6P (Winkler et al. 2004). This observation established the seemingly simple hypothesis that signal-induced self-cleavage might be coupled to intracellular stability of the glmS transcript. A challenge for this mechanistic model lies in the extensive data regarding mRNA degradation pathways in E. coli, the primary organism used for study of bacterial mRNA decay (Grunberg-Manago 1999; Coburn and Mackie 1999; Carpousis 2002; Condon 2003; Kushner 2004; Deutscher 2006). In this microbe, the RNase E endoribonuclease associates with the 5′ terminus of mRNAs and cleaves internally at AU-rich regions, resulting in RNA products with 3′ hydroxyl and 5′ monophosphate termini. Since RNase E exhibits the greatest affinity for substrates containing 5′ monophosphate groups it then rapidly subjects the latter RNAs to further cleavage reactions. Products of RNase E cleavage are further degraded through the combined action of multiple 3′–5′ exoribonucleases. Based on this logic, one might expect an RNA element that entrained self-cleavage activity for genetic purposes to produce a downstream product containing a 5′ monophosphate group, thereby signaling the downstream transcript for degradation by RNase E. However, the glmS ribozyme has been clearly established to produce products containing 2′,3′ cyclic phosphate and 5′ hydroxyl groups on the upstream and downstream RNAs, respectively (Winkler et al. 2004; Klein and Ferre-D’Amare 2006; Cochrane et al. 2007; Klein et al. 2007). RNA substrates containing 5′ hydroxyl groups in fact exhibit the poorest affinity for RNase E-mediated degradation (Jiang et al. 2000; Tock et al. 2000; Celesnik et al. 2007). Furthermore, although RNase E has been established as a core component governing mRNA decay in E. coli, it is absent in many bacterial lineages, and it is still unknown how well data from E. coli will extrapolate to other micro-organisms. The glmS ribozyme therefore provides a window into mRNA degradation pathways in Gram-positive bacteria and allows for investigations into the basic principles of ribozyme-mediated control of gene expression.

Our data herein reveal that the GlcN6P-sensing B. subtilis glmS ribozyme indeed wields its regulatory influence over mRNA stability, rather than affecting transcriptional elongation or translation initiation. This genetic activity relies on the specific destabilization of the 3′ cleavage product upon GlcN6P stimulation of self-cleavage. Moreover, the recently discovered RNase J1 protein is explicitly required for degradation of the 3′ cleavage product for hammerhead and glmS ribozymes. The fact that targeting of transcripts by RNase J1 occurs with RNAs containing a 5′ hydroxyl, but not in response to those with a 5′ triphosphate group, establishes two hypotheses. First, the RNase J1 protein is likely to behave, at least in part, similar to RNase E with regard to its reliance on molecular identity at the 5′ terminus. Therefore, recognition of the 5′ terminus may be a rate-limiting step in mRNA turnover for bacteria in general, as opposed to being a unique requirement by E. coli. However, these data also suggest that there are likely to be fundamental biochemical differences between the RNase E and RNase J1 ribonucleases. Given the widespread biological distribution of RNase J in bacteria (Even et al. 2005), comparative analyses of these proteins will be necessary before generalizations into bacterial mRNA turnover can be established. Interestingly, a recent report suggests that the RNase J enzyme is capable of 5′–3′ exoribonuclease activity (Mathy et al. 2007). Our data, demonstrating an in vivo preference for hydroxyl-terminated RNAs by RNase J1, agree well with the observation that RNA substrates containing either 5′ hydroxyl or 5′ monophosphate groups were the preferred substrates for exoribonuclease activity by RNase J1 (Mathy et al. 2007).

These studies help elucidate some of the basic processes involved in bacterial mRNA decay pathways and highlight similarities and differences between B. subtilis and the E. coli paradigm. In addition to shedding light on mRNA degradation mechanisms in Gram-positive bacteria, the study of the glmS ribozyme mechanism will assist in developing an experimental framework from which the molecular engineering of “designer” chemical-responsive ribozymes can be built. Furthermore, the demonstration that the RNase J1 protein, which is broadly distributed in eubacterial organisms, can selectively target RNAs containing a 5′ hydroxyl terminus suggests that other signal-responsive self-cleaving regulatory ribozymes may still await discovery.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and oligonucleotides

All chemicals, unless otherwise noted, were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. DNA oligonucleotides were purchased from either Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. or Sigma-Aldrich. Exact nucleotide sequences and a brief description of DNA oligonucleotides used in these studies can be found in the Supplemental Material.

Strains and growth conditions

The B. subtilis strains used in this study were all derivatives from strain BR151 (Bacillus Genetic Stock Center [BGSC]). Fusion of the glmS 5′ UTR with lacZ is described elsewhere (Winkler et al. 2004). DNA oligonucleotides with added restriction sites were used to amplify the glmS regulatory region. Nucleotides from −386 to +39 relative to the translation start site were cloned into pDG1661 (BGSC) via JC10 and JC11 DNA primers. Plasmid pDG1661 contains regions of the amyE gene that flank the ribozyme–lacZ fusions and was thereby used to integrate these sequences within the amyE gene via double homologous recombination (see Dann et al. 2007 for more details). For the promoter–lacZ fusion, nucleotides from −358 to −301 relative to the translation start site were cloned into plasmid pDG1661 via WCW417, WCW418 primers. For the translational glmS fusion, nucleotides from −386 to +39 relative to the translation start site were ligated into an altered form of pDG1661 (data not shown), which contained an extra BamH1 site within the N terminus of lacZ. Specifically, the sequence surrounding the third codon of lacZ was altered from GTGGAAGTTACTGAC GTA to GTGGAGGATCCTGACGTA, thereby introducing a BamH1 site. Using this site, the 13th glmS codon was placed in-frame with the third lacZ codon. The M9 mutant was created as described elsewhere (Winkler et al. 2004). The M11 mutant was created through PCR-sewing of overlapping oligos such that nucleotide +162 was directly fused to +236 (numbering relative to the site of self-cleavage as shown in Fig. 1A); the resulting insert was cloned into pDG1661 via restriction sites added from flanking primers JC10 and JC11 (see Supplemental Material). For creation of M12, nucleotides −356 to −311 relative to the translation start site were fused directly to −251 to −233 relative to the translation start site via amplification with IRV5 and JC11 (see Supplemental Material). This resulted in placement of the endogenous glmS promoter upstream of the glmS sequence such that transcription initiation occurred with G + 1 (numbering relative to site of self-cleavage as shown in Fig. 1A). The latter construct was verified by 5′ mapping experimentation (Fig. 5; data not shown). Sequences for all constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Construction of inducible glmS strains

DNA oligonucleotides WCW261, JC11, WCW257, WCW258, WCW259, and WCW260 were used to PCR-amplify the “left” and “right” regions of the glmS gene as well as an erm cassette that was placed between them. The erm cassette was amplified from plasmid pMUTIN4 (BGSC) using primers WCW257 and WCW258. All of these fragments were then cloned into plasmid pBGSC6 (BGSC) via restriction sites added during PCR amplification (see oligonucleotide sequences in Supplemental Material). This plasmid was used for allelic replacement of the glmS gene with the erm cassette via double-crossover homologous recombination. The “left” and “right” glmS portions included nucleotides from −527 to +38 and +1541 to +1794 relative to the glmS translation start site, respectively. DNA oligonucleotides JC29 and JC30 were used to amplify the glmS coding sequence for cloning into plasmid pDG148. B. subtilis cells (strain BR151; BGSC) were transformed with the pDG148-glmS plasmid using methods described elsewhere (Jarmer et al. 2002; Dann et al. 2007). These cells were then transformed with the pBGSC6-based, erm-containing, glmS deletion plasmid and plated on glucose minimal medium under conditions that included 1 mM IPTG. The resulting transformants were screened for IPTG dependence. The region encompassing the original glmS locus was then PCR-amplified for a subset of IPTG-dependent isolates and subjected to DNA sequencing analysis in order to verify replacement of the glmS gene with erm.

Construction of E. coli strain with inducible RNase J1 and hammerhead-rpsT

DNA oligonucleotides IRV27 and IRV28 were used to PCR-amplify rnjA gene (RNase J1) from B. subtilis chromosomal DNA. The resulting PCR product was then cloned into plasmid pBAD/Myc-His A (Invitrogen) under an arabinose-inducible promoter using NcoI and HindIII restriction sites added during PCR amplification. A stop codon was included in the insert such that the resulting protein would not contain myc and his epitopes. The rpsT gene was amplified from the chromosomal DNA of E. coli strain DH5α. The B. subtilis glmS promoter and hammerhead ribozyme were fused to the 5′ end using DNA oligonucleotides IRV144, IRV145, IRV146, IRV134, and IRV135 (see Supplemental Material). A 19-base-pair (bp) sequence tag (5′-AGAC CCCCACCCCGATTCTT-3′) (Celesnik et al. 2007) was also fused to the 3′ UTR of the rpsT gene via PCR amplification. The resulting fragment was cloned into plasmid pACYC184 (New England Biolabs). Both plasmids, containing inducible RNaseJ1 and hammerhead-rpsT constructs, were then transformed into E. coli strain DH5α.

Growth conditions

All B. subtilis strains were either cultured in defined glucose minimal medium (described elsewhere) (Dann et al. 2007) or rich medium (2XYT). The strains that relied on an ITPG-inducible copy of glmS were cultured in glucose minimal medium in the presence of varying IPTG. To assay for IPTG dependency, a 10-mL aliquot of this media was inoculated and left standing overnight at 37°C. The following morning the cells were incubated shaking at 37°C until reaching mid-exponential growth phase whereupon they were pelleted and washed at least twice in medium lacking IPTG. The cell pellets were then resuspended to an OD600 = 0.1 and split into two equal aliquots. To one aliquot was added 5 mM IPTG while no or low IPTG was added to the other. The two parallel cultures were then incubated shaking at 37°C. Aliquots were removed at different time intervals for OD600 and experimental analyses (β-galactosidase activity assays, RNA extraction).

Strain GP41, containing a xylose-inducible copy of rnjA (RNase J1) (generous gift from Jörg Stülke, University of Göttingen, Germany), was cultured in rich media in the presence or absence of 1.5% xylose to mid-exponential phase growth whereupon cells were harvested for OD600 and experimental analyses (β-galactosidase activity assays, RNA extraction). The original GP41 strain maintains the inducible copy of rnjA via a chloramphenicol resistance cassette. However, for our analyses, plasmid pCm∷Nm (BGSC) was used to swap cat for neo, encoding for neomycin resistance, for construction of strain GP41-neo. This then allowed for transformation of GP41 with pDG1661 plasmids that contained glmS–lacZ fusions with selection for the cat gene (5 μg/mL). To construct a strain containing disruption of rnjB (RNase J2) as well as the xylose-inducible control of rnjA (RNase J1), GP41-neo cells were transformed with chromosomal DNA extracted from strain SSB348 (gift from H. Putzer, Institut de Biologie Physico-Chimique, Paris, France) (Even et al. 2005), and the resulting transformants were selected for resistance to neomycin (5 μg/mL) and tetracycline (5 μg/mL). These cells were also assayed for xylose dependency.

E. coli strain DH5α containing inducible RNase J1 and hammerhead-rpsT constructs was grown in RM medium (per liter: 2% casamino acids [w/v], 0.2% glucose [w/v], 1 mM MgCl2, 6 g of Na2HPO4, 3 g of KH2PO4, 0.5 g of NaCl, 1 g of NH4Cl; adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH) in the presence of ampicillin (50 μg/mL) and chloramphenicol (30 μg/mL). To assay for the effect of RNase J1, the cells were cultured at 37°C with shaking until reaching OD600 = 0.2 and then split into two equal aliquots. L-arabinose (0.2%) was added to one aliquot, while no arabinose was added to the other. The two cultures were then grown to mid-exponential phase growth before being harvested for total RNA samples. For DH5α containing only hammerhead-rpsT, the cells were cultured in RM medium in the presence of chloramphenicol (30 μg/mL) until reaching mid-exponential phase growth whereupon cells were harvested for total RNA.

β-Galactosidase activity assays

Assays for lacZ expression were conducted as described elsewhere (Dann et al. 2007).

Sporulation assay

B. subtilis strains were induced into sporulation by the resuspension method as described elsewhere (Sterlini and Mandelstam 1969; Nicholson and Setlow 1990). For microscopy analysis, 5 μL of the sporulating cells were spotted onto a 1.5% agarose pad (in 1× PBS), dried for 1 h at 37°C, and viewed at 60× magnification via phase contrast microscopy, using an Olympus IX81 motorized inverted microscope.

RNA extraction

Total RNA was harvested from B. subtilis strains cultured at 37°C as described above. These cells were pelleted, resuspended in LETS buffer (0.1 M LiCl, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM TrisHCl, 1% SDS), vortexed with acid-washed glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 min and incubated for 5 min at 55°C. The resulting solution was subjected to extraction by TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA was then concentrated by ethanol precipitation and quantified via absorbance spectroscopy.

Northern blot analyses

Total RNA samples (20 μg) were heated for 10 min at 65°C in 1× gel loading buffer (45 mM Tris-borate, 4 M urea, 10% sucrose [w/v], 5 mM EDTA, 0.05% SDS, 0.025% xylene cyanol FF, 0.025% bromophenol blue) and resolved by either 6% denaturing (8 M urea) polyacrylamide electrophoresis or formaldehyde denaturing 1%–2% agarose gel electrophoresis. RNAs were transferred to BrightStar-Plus nylon membranes (Ambion) using a semidry electroblotting apparatus (Owl Scientific) according to manufacturers’ instructions. The blots were UV-cross-linked and hybridized overnight in UltraHyb buffer (Ambion) with either 5′-radiolabeled (32P) DNA oligonucleotide or internally radiolabeled (32P) probe RNA. To detect rpsT transcripts, IRV136 DNA oligonucleotide probe was hybridized overnight to the blots at 42°C and washed twice for 15 min using low-stringency wash buffer followed by a 30-min wash using high-stringency buffer. The latter antisense RNA probes, which constituted the reverse complementary sequence of the glmS 5′ UTR, were transcribed in vitro from PCR templates generated from either IRV43–IRV44 or WCW409–WCW410 oligonucleotide primer pairs, and were PAGE-purified. Briefly, for these reactions ∼10–30 pmol DNA templates, prepared by PCR using appropriate oligonucleotide primers, were incubated for 2.5 h at 37°C in 25-μL reactions that contained 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1 mM spermidine-HCl, 0.5 mM GTP, 0.5 mM ATP, 0.5 mM CTP, 0.05 mM UTP, 4 μL of [α-32P]UTP (10 μCi/μL), and ∼25 μg/mL T7 RNA polymerase. The resulting RNA transcripts were resolved by denaturing 6% PAGE, excised and passively eluted in 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) for <2 h at 23°C. The antisense RNA probes were then ethanol-precipitated and quantified by A260. After hybridization with the radiolabeled probes, the blots were washed twice for 5 min with low-stringency wash buffer (1× SCC, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA) at room temperature followed by a high-stringency wash (0.2× SCC, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA) for 15 min at 68°C. Cellular 5S RNA was hybridized against either an internally radiolabeled antisense RNA probe (transcribed from PCR templates derived from either the WCW407–WCW408 or IRV104–IRV105 primer pair) or a 5′-radiolabeled DNA oligonucleotide (IRV120 for B. subtilis, IRV18 for E. coli). The DNA oligonucleotide probe was hybridized to the blots at 42°C and washed twice for 15 min using low-stringency wash buffer. Radioactive bands were visualized using ImageQuant software and a Typhoon PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Reverse transcription qPCR

Total RNA from strains was isolated as described above. Four micrograms of RNA were then incubated in 20-μL reactions with 2 U of DNase (Roche) and 0.5 mM MgCl2. These reactions were incubated for 30 min at 37°C followed by 10 min at 75°C. The resulting RNA samples were used for synthesis of cDNA libraries, which were generated using the iScript Select cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) as per manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 0.5–1.0 μg of RNA and random hexamer primers were included in these cDNA synthesis reactions. Control reactions lacking RT were also prepared for each different RNA sample. DNA primers were designed with assistance of PrimerExpress in order to amplify an ∼100-bp amplicon. For qPCR, all reactions were prepared in triplicate in MicroAmp optical 384-well reaction plates (ABI). Each reaction contained 150 nM primers, 5 μL of 2× SYBR Green master mix, and 25 ng of cDNA templates in a total volume of 10 μL. The cycling parameters used for these experiments were as follows: 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C, using an ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR instrument. The number of cycles required to reach threshold fluorescence (Ct) was determined through use of Sequence Detection Systems version 2.2.2 software (Applied Biosystems) using automatic baseline and threshold determination and averaged from triplicate samples. Ct values for 5S control RNAs were subtracted from experimental values to give ΔCt values, which were averaged from data performed in triplicate. These values were used to establish the ratio of transcript abundances for ribozyme-containing transcripts during conditions of high and low GlcN6P. The formula used to calculate this ratio was 2(ΔCt low − ΔCt high). For each primer set, a control reaction lacking cDNA templates was included. Additionally, melting curve analyses were conducted on all qPCR products in order to verify production of single amplicon products.

Primer extension analyses of ribozyme-containing transcripts

Fifteen to thirty micrograms of total RNA were treated with 10 U of DNase I (Roche) in the presence of 0.25 mM MgCl2 for 30 min at 37°C. Following phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation steps, the RNA was subjected to reverse transcription reactions using a 5′-radiolabeled DNA primer specific for the glmS 5′ UTR (JC43) and Transcriptor RT (Roche), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Dideoxy DNA sequencing ladders were generated using the same DNA oligonucleotide (JC43) and the Thermo Sequenase Cycle Sequencing Kit (USB). As a control for total RNA quantities, 5S RNA was reverse-transcribed using a separate 5′-radiolabeled DNA primer (IRV13).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Gürol Süel and Tolga Cagatay for help with photography of B. subtilis spores. We are grateful to the Winkler research group and J. Kenneth Wickiser for offering comments on the manuscript. We thank Catherine Wakeman for some experimental assistance in these studies. We are grateful to Jörg Stülke and Harald Putzer for the gift of B. subtilis strains containing inducible RNase J1 and for a strain deleted for RNase J2. This research was funded by The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Endowed Scholars Program, Welch Foundation I-1643, and the Searle Scholars Program.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1605307

References

- Arnold T.E., Yu J., Belasco J.G., Yu J., Belasco J.G., Belasco J.G. mRNA stabilization by the ompA 5′ untranslated region: Two protective elements hinder distinct pathways for mRNA degradation. RNA. 1998;4:319–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrick J.E., Corbino K.A., Winkler W.C., Nahvi A., Mandal M., Collins J., Lee M., Roth A., Sudarsan N., Jona I., Corbino K.A., Winkler W.C., Nahvi A., Mandal M., Collins J., Lee M., Roth A., Sudarsan N., Jona I., Winkler W.C., Nahvi A., Mandal M., Collins J., Lee M., Roth A., Sudarsan N., Jona I., Nahvi A., Mandal M., Collins J., Lee M., Roth A., Sudarsan N., Jona I., Mandal M., Collins J., Lee M., Roth A., Sudarsan N., Jona I., Collins J., Lee M., Roth A., Sudarsan N., Jona I., Lee M., Roth A., Sudarsan N., Jona I., Roth A., Sudarsan N., Jona I., Sudarsan N., Jona I., Jona I., et al. New RNA motifs suggest an expanded scope for riboswitches in bacterial genetic control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:6421–6426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308014101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belasco J.G., Beatty J.T., Adams C.W., von Gabain A., Cohen S.N., Beatty J.T., Adams C.W., von Gabain A., Cohen S.N., Adams C.W., von Gabain A., Cohen S.N., von Gabain A., Cohen S.N., Cohen S.N. Differential expression of photosynthesis genes in R. capsulata results from segmental differences in stability within the polycistronic rxcA transcript. Cell. 1985;40:171–181. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun F., Le Derout L., Regnier P., Le Derout L., Regnier P., Regnier P. Ribosomes inhibit an RNase E cleavage which induces the decay of the rpsO mRNA of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1998;17:4790–4797. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaker R.R. Natural and engineered nucleic acids as tools to explore biology. Nature. 2004;432:838–845. doi: 10.1038/nature03195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton R.A., Wen T., Schaefer L., Pellegrini O., Uicker W.C., Mathy N., Tobin C., Daou R., Szyk J., Condon C., Wen T., Schaefer L., Pellegrini O., Uicker W.C., Mathy N., Tobin C., Daou R., Szyk J., Condon C., Schaefer L., Pellegrini O., Uicker W.C., Mathy N., Tobin C., Daou R., Szyk J., Condon C., Pellegrini O., Uicker W.C., Mathy N., Tobin C., Daou R., Szyk J., Condon C., Uicker W.C., Mathy N., Tobin C., Daou R., Szyk J., Condon C., Mathy N., Tobin C., Daou R., Szyk J., Condon C., Tobin C., Daou R., Szyk J., Condon C., Daou R., Szyk J., Condon C., Szyk J., Condon C., Condon C. Maturation of the 5′ end of Bacillus subtilis 16S rRNA by the essential ribonuclease YkqC/RNase J1. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:127–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpousis A.J. The Escherichia coli RNA degradosome: Structure, function and relationship in other ribonucleolytic multienzyme complexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002;30:150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celesnik H., Deana A., Belasco J.G., Deana A., Belasco J.G., Belasco J.G. Initiation of RNA decay in Escherichia coli by 5′ pyrophosphate removal. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn G.A., Mackie G.A., Mackie G.A. Degradation of mRNA in Escherichia coli: An old problem with some new twists. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1999;62:55–108. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60505-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane J.C., Lipchock S.V., Strobel S.A., Lipchock S.V., Strobel S.A., Strobel S.A. Structural investigation of the glmS ribozyme bound to its catalytic cofactor. Chem. Biol. 2007;14:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon C. RNA processing and degradation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003;67:157–174. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.2.157-174.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon C. Maturation and degradation of RNA in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2007;10:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon C., Putzer H., Putzer H. The phylogenetic distribution of bacterial ribonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:5339–5346. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbino K.A., Barrick J.E., Lim J., Welz R., Tucker B.J., Puskarz I., Mandal M., Rudnick N.D., Breaker R.R., Barrick J.E., Lim J., Welz R., Tucker B.J., Puskarz I., Mandal M., Rudnick N.D., Breaker R.R., Lim J., Welz R., Tucker B.J., Puskarz I., Mandal M., Rudnick N.D., Breaker R.R., Welz R., Tucker B.J., Puskarz I., Mandal M., Rudnick N.D., Breaker R.R., Tucker B.J., Puskarz I., Mandal M., Rudnick N.D., Breaker R.R., Puskarz I., Mandal M., Rudnick N.D., Breaker R.R., Mandal M., Rudnick N.D., Breaker R.R., Rudnick N.D., Breaker R.R., Breaker R.R. Evidence for a second class of S-adenosylmethionine riboswitches and other regulatory RNA motifs in α-proteobacteria. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R70. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-8-r70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromie M.J., Shi Y., Latifi T., Groisman E.A., Shi Y., Latifi T., Groisman E.A., Latifi T., Groisman E.A., Groisman E.A. An RNA sensor for intracellular Mg2+ Cell. 2006;125:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dann C.D., Wakeman C.A., Sieling C.L., Baker S.C., Irnov I., Winkler W.C., Wakeman C.A., Sieling C.L., Baker S.C., Irnov I., Winkler W.C., Sieling C.L., Baker S.C., Irnov I., Winkler W.C., Baker S.C., Irnov I., Winkler W.C., Irnov I., Winkler W.C., Winkler W.C. Structure and mechanism of a metal-sensing regulatory RNA. Cell. 2007;130:878–892. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deana A., Belasco J.G., Belasco J.G. Lost in translation: The influence of ribosomes on bacterial mRNA decay. Genes & Dev. 2005;19:2526–2533. doi: 10.1101/gad.1348805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher M.P. Degradation of RNA in bacteria: Comparison of mRNA and stable RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:659–666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diwa A., Bricker A.L., Jain C., Belasco J.G., Bricker A.L., Jain C., Belasco J.G., Jain C., Belasco J.G., Belasco J.G. An evolutionary conserved RNA stem–loop functions as a sensor that directs feedback regulation of RNase E gene expression. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:1249–1260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doudna J.A., Cech T.R., Cech T.R. The chemical repertoire of natural ribozymes. Nature. 2002;418:222–228. doi: 10.1038/418222a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus M., Regnier P., Regnier P. The poly(A) tail of mRNAs: Bodyguard in eukaryotes, scavenger in bacteria. Cell. 2002;111:611–613. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emory S.A., Bouvet P., Belasco J.G., Bouvet P., Belasco J.G., Belasco J.G. A 5′-terminal stem–loop structure can stabilize mRNA in Escherichia coli. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:135–148. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Even S., Pellegrini O., Zig L., Labas V., Vinh J., Brechemmier-Baey D., Putzer H., Pellegrini O., Zig L., Labas V., Vinh J., Brechemmier-Baey D., Putzer H., Zig L., Labas V., Vinh J., Brechemmier-Baey D., Putzer H., Labas V., Vinh J., Brechemmier-Baey D., Putzer H., Vinh J., Brechemmier-Baey D., Putzer H., Brechemmier-Baey D., Putzer H., Putzer H. Ribonucleases J1 and J2: Two novel endoribonucleases in B. subtilis with functional homology to E. coli RNase E. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2141–2152. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedor M.J., Williamson J.R., Williamson J.R. The catalytic diversity of RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:399–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folichon M., Arluison V., Pellegrini O., Huntzinger E., Regnier P., Hajnsdorf E., Arluison V., Pellegrini O., Huntzinger E., Regnier P., Hajnsdorf E., Pellegrini O., Huntzinger E., Regnier P., Hajnsdorf E., Huntzinger E., Regnier P., Hajnsdorf E., Regnier P., Hajnsdorf E., Hajnsdorf E. The poly(A) binding protein Hfq protects RNA from RNase E and exoribonucleolytic degradation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:7302–7310. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert S.D., Batey R.T., Batey R.T. Riboswitches: Fold and function. Chem. Biol. 2006;13:805–807. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatz E., Nilsson R.P., Rutberg L., Rutberg B., Nilsson R.P., Rutberg L., Rutberg B., Rutberg L., Rutberg B., Rutberg B. A dual role for the Bacillus subtilis glpD leader and the GlpP protein in the regulated expression of glpD: Antitermination and control of mRNA stability. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;19:319–328. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.376903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman S., McCullen C.A., Guillier M., Vanderpool C.K., Majdalani N., Benhammou J., Thompson K.M., FitzGerald P.C., Sowa N.A., FitzGerald D.J., McCullen C.A., Guillier M., Vanderpool C.K., Majdalani N., Benhammou J., Thompson K.M., FitzGerald P.C., Sowa N.A., FitzGerald D.J., Guillier M., Vanderpool C.K., Majdalani N., Benhammou J., Thompson K.M., FitzGerald P.C., Sowa N.A., FitzGerald D.J., Vanderpool C.K., Majdalani N., Benhammou J., Thompson K.M., FitzGerald P.C., Sowa N.A., FitzGerald D.J., Majdalani N., Benhammou J., Thompson K.M., FitzGerald P.C., Sowa N.A., FitzGerald D.J., Benhammou J., Thompson K.M., FitzGerald P.C., Sowa N.A., FitzGerald D.J., Thompson K.M., FitzGerald P.C., Sowa N.A., FitzGerald D.J., FitzGerald P.C., Sowa N.A., FitzGerald D.J., Sowa N.A., FitzGerald D.J., FitzGerald D.J. Small RNA regulators and the bacterial response to stress. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2006;71:1–11. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S., Moxon S., Marshall M., Khanna A., Eddy S.R., Bateman A., Moxon S., Marshall M., Khanna A., Eddy S.R., Bateman A., Marshall M., Khanna A., Eddy S.R., Bateman A., Khanna A., Eddy S.R., Bateman A., Eddy S.R., Bateman A., Bateman A. Rfam: Annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D121–D124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunberg-Manago M. Messenger RNA stability and its role in control of gene expression in bacteria and phages. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1999;33:193–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambraeus G., Persson M., Rutberg B., Persson M., Rutberg B., Rutberg B. The aprE leader is a determinant of extreme mRNA stability in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 2000;146:3051–3059. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-12-3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel K.J., Tinsley M.M., Tinsley M.M. Evidence for preorganization of the glmS ribozyme ligand binding pocket. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7861–7871. doi: 10.1021/bi060337z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irnov A., Winkler W.C., Winkler W.C. Genetic control by cis-acting regulatory RNAs in Bacillus subtilis: General principles and prospects for discovery. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2006;71:239–249. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmer H., Berka R., Knudsen S., Saxild H.H., Berka R., Knudsen S., Saxild H.H., Knudsen S., Saxild H.H., Saxild H.H. Transcriptome analysis documents induced competence of Bacillus subtilis during nitrogen limiting conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2002;206:197–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Belasco J.G., Belasco J.G. Catalytic activation of multimeric RNase E and RNase G by 5′-monophosphorylated RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:9211–9216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401382101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Diwa A., Belasco J.G., Diwa A., Belasco J.G., Belasco J.G. Regions of RNase E important for 5′-end-dependent RNA cleavage and autoregulated synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:2468–2475. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.9.2468-2475.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joanny G., Le Derout J., Brechemier-Baey D., Labas V., Vinh J., Regnier P., Hajnsdorf E., Le Derout J., Brechemier-Baey D., Labas V., Vinh J., Regnier P., Hajnsdorf E., Brechemier-Baey D., Labas V., Vinh J., Regnier P., Hajnsdorf E., Labas V., Vinh J., Regnier P., Hajnsdorf E., Vinh J., Regnier P., Hajnsdorf E., Regnier P., Hajnsdorf E., Hajnsdorf E. Polyadenylation of a functional mRNA controls gene expression in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2494–2502. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D.J., Ferre-D’Amare A.R., Ferre-D’Amare A.R. Structural basis of glmS ribozyme activation by glucosamine-6-phosphate. Science. 2006;313:1752–1756. doi: 10.1126/science.1129666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D.J., Wilkinson S.R., Been M.D., Ferre-D’Amare A.R., Wilkinson S.R., Been M.D., Ferre-D’Amare A.R., Been M.D., Ferre-D’Amare A.R., Ferre-D’Amare A.R. Requirement of helix P2.2 and nucleotide G1 for positioning the cleavage site and cofactor of the glmS ribozyme. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;373:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Ehrlich S.D., Albertini A., Amati G., Andersen K.K., Arnaud M., Asai K., Ashikaga S., Aymerich S., Bessieres P., Ehrlich S.D., Albertini A., Amati G., Andersen K.K., Arnaud M., Asai K., Ashikaga S., Aymerich S., Bessieres P., Albertini A., Amati G., Andersen K.K., Arnaud M., Asai K., Ashikaga S., Aymerich S., Bessieres P., Amati G., Andersen K.K., Arnaud M., Asai K., Ashikaga S., Aymerich S., Bessieres P., Andersen K.K., Arnaud M., Asai K., Ashikaga S., Aymerich S., Bessieres P., Arnaud M., Asai K., Ashikaga S., Aymerich S., Bessieres P., Asai K., Ashikaga S., Aymerich S., Bessieres P., Ashikaga S., Aymerich S., Bessieres P., Aymerich S., Bessieres P., Bessieres P., et al. Essential Bacillus subtilis genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:4678–4683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730515100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner S.R. mRNA decay in prokaryotes and eukaryotes: Different approaches to a similar problem. IUBMB Life. 2004;56:585–594. doi: 10.1080/15216540400022441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landick R., Yanofsky C., Yanofsky C. Transcription attenuation. In: Neidhardt F.C., editor. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: Cellular and molecular biology. American Society for Microbiology; Washington, DC: 1987. pp. 1276–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Pandit S., Deutscher M.P., Pandit S., Deutscher M.P., Deutscher M.P. Polyadenylation of stable RNA precursors in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:12158–12162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M.Y., Yang H., Romeo T., Yang H., Romeo T., Romeo T. The product of the pleiotropic Escherichia coli gene csrA modulates glycogen biosynthesis vie effects on mRNA stability. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:2663–2672. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2663-2672.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie G.A. Ribonuclease E is a 5′-end-dependent endonuclease. Nature. 1998;395:720–723. doi: 10.1038/27246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M., Breaker R.R., Breaker R.R. Adenine riboswitches and gene activation by disruption of a transcription terminator. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:29–35. doi: 10.1038/nsmb710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M., Lee M., Barrick J.E., Weinberg Z., Emilsson G.M., Ruzzo W.L., Breaker R.R., Lee M., Barrick J.E., Weinberg Z., Emilsson G.M., Ruzzo W.L., Breaker R.R., Barrick J.E., Weinberg Z., Emilsson G.M., Ruzzo W.L., Breaker R.R., Weinberg Z., Emilsson G.M., Ruzzo W.L., Breaker R.R., Emilsson G.M., Ruzzo W.L., Breaker R.R., Ruzzo W.L., Breaker R.R., Breaker R.R. A glycine-dependent riboswitch that uses cooperative binding to control gene expression. Science. 2004;306:275–279. doi: 10.1126/science.1100829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathy N., Benard L., Pellegrini O., Daou R., Wen T., Condon C., Benard L., Pellegrini O., Daou R., Wen T., Condon C., Pellegrini O., Daou R., Wen T., Condon C., Daou R., Wen T., Condon C., Wen T., Condon C., Condon C. 5′-to-3′ exoribonuclease activity in bacteria: Role of RNase J1 in rRNA maturation and 5′ stability of mRNA. Cell. 2007;129:681–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy T.J., Plog M.A., Floy S.A., Jansen J.A., Soukup J.K., Soukup G.A., Plog M.A., Floy S.A., Jansen J.A., Soukup J.K., Soukup G.A., Floy S.A., Jansen J.A., Soukup J.K., Soukup G.A., Jansen J.A., Soukup J.K., Soukup G.A., Soukup J.K., Soukup G.A., Soukup G.A. Ligand requirements for glmS ribozyme self-cleavage. Chem. Biol. 2005;12:1221–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowall K.J., Kaberdin V.R., Wu S., Cohen S.N., Lin-Chao S., Kaberdin V.R., Wu S., Cohen S.N., Lin-Chao S., Wu S., Cohen S.N., Lin-Chao S., Cohen S.N., Lin-Chao S., Lin-Chao S. Site-specific RNase E cleavage of oligonucleotides and inhibition by stem–loops. Nature. 1995;374:287–290. doi: 10.1038/374287a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren R.S., Newbury S.F., Dance G.S., Causton H.C., Higgins C.F., Newbury S.F., Dance G.S., Causton H.C., Higgins C.F., Dance G.S., Causton H.C., Higgins C.F., Causton H.C., Higgins C.F., Higgins C.F. mRNA degradation by processive 3′–5′ exoribonucleases in vitro and the implications for prokaryotic mRNA decay in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;221:81–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson W.L., Setlow P., Setlow P. Sporulation, germination and outgrowth. In: Harwood C.R., Cutting S.M., Cutting S.M., editors. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley; Chichester, West Sussex, UK: 1990. pp. 391–431. [Google Scholar]

- Roth A., Nahvi A., Lee M., Jona I., Breaker R.R., Nahvi A., Lee M., Jona I., Breaker R.R., Lee M., Jona I., Breaker R.R., Jona I., Breaker R.R., Breaker R.R. Characteristics of the glmS ribozyme suggest only structural roles for divalent metal ions. RNA. 2006;12:607–619. doi: 10.1261/rna.2266506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A., Winkler W.C., Regulski E.E., Lee B.W., Lim J., Jona I., Barrick J.E., Ritwik A., Kim J.N., Welz R., Winkler W.C., Regulski E.E., Lee B.W., Lim J., Jona I., Barrick J.E., Ritwik A., Kim J.N., Welz R., Regulski E.E., Lee B.W., Lim J., Jona I., Barrick J.E., Ritwik A., Kim J.N., Welz R., Lee B.W., Lim J., Jona I., Barrick J.E., Ritwik A., Kim J.N., Welz R., Lim J., Jona I., Barrick J.E., Ritwik A., Kim J.N., Welz R., Jona I., Barrick J.E., Ritwik A., Kim J.N., Welz R., Barrick J.E., Ritwik A., Kim J.N., Welz R., Ritwik A., Kim J.N., Welz R., Kim J.N., Welz R., Welz R., et al. A riboswitch selective for the queuosine precursor preQ1 contains an unusually small aptamer domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:308–317. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbe H., Buck J., Furtig B., Noeske J., Wohnert J., Buck J., Furtig B., Noeske J., Wohnert J., Furtig B., Noeske J., Wohnert J., Noeske J., Wohnert J., Wohnert J. Structures of RNA switches: Insight into molecular recognition and tertiary structure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2007;46:1212–1219. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp J.S., Bechhofer D.H., Bechhofer D.H. Effect of translational signals on mRNA decay in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:5372–5379. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.18.5372-5379.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp J.S., Bechhofer D.H., Bechhofer D.H. Effect of 5′-proximal elements on decay of a model mRNA in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;57:484–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]