Abstract

Background

There is considerable variability in reported postoperative mortality and risk factors for mortality after surgery for lung cancer. Population‐based data provide unbiased estimates and may aid in treatment selection.

Methods

All patients diagnosed with lung cancer in Norway from 1993 to the end of 2005 were reported to the Cancer Registry of Norway (n = 26 665). A total of 4395 patients underwent surgical resection and were included in the analysis. Data on demographics, tumour characteristics and treatment were registered. A subset of 1844 patients was scored according to the Charlson co‐morbidity index. Potential factors influencing 30‐day mortality were analysed by logistic regression.

Results

The overall postoperative mortality rate was 4.4% within 30 days with a declining trend in the period. Male sex (OR 1.76), older age (OR 3.38 for age band 70–79 years), right‐sided tumours (OR 1.73) and extensive procedures (OR 4.54 for pneumonectomy) were identified as risk factors for postoperative mortality in multivariate analysis. Postoperative mortality at high‐volume hospitals (⩾20 procedures/year) was lower (OR 0.76, p = 0.076). Adjusted ORs for postoperative mortality at individual hospitals ranged from 0.32 to 2.28. The Charlson co‐morbidity index was identified as an independent risk factor for postoperative mortality (p = 0.017). A prediction model for postoperative mortality is presented.

Conclusions

Even though improvements in postoperative mortality have been observed in recent years, these findings indicate a further potential to optimise the surgical treatment of lung cancer. Hospital treatment results varied but a significant volume effect was not observed. Prognostic models may identify patients requiring intensive postoperative care.

Lung cancer takes more lives than any other cancer in the USA, European Union and Norway.1,2,3 Surgery is the mainstay of curative therapy and results in 5‐year relative survival rates up to 72% for the most favourable tumour stages.4 An active approach to referral for surgery of patients with lung cancer should therefore be advocated.

Unfortunately, lung cancer often requires extensive resection to ensure that the tumour and possibly involved lymph nodes are completely removed. As a consequence, surgical treatment may be associated with high complication rates, morbidity and mortality, especially in elderly patients with severe co‐morbidities, as reflected by the lower resection rates for this group.5,6

The Charlson co‐morbidity index (CCI) represents a simple and robust classification of co‐morbidity.5,7 Although the CCI is regarded as a reliable predictor of risk for complications and short‐term and long‐term survival, it has not been specifically validated for postoperative mortality.5,8,9,10 Substantial variation in postoperative mortality has been reported by other countries and institutions, but direct comparison is hampered by differences in definitions and selection criteria. For major resections, operative mortality in excess of 10% have been reported in other studies, although recent data suggest improvement.11,12,13 Case series from large clinics tend to show lower mortality than population‐based studies.13,14 This could be explained by the superior performance of specialised institutions but might also be caused by selection bias.15

We previously reported the specific causes of death in a subset of the present patient population.16 The aim of the present study is to perform a formal statistical assessment of risk factors for 30‐day postoperative mortality in an unselected population‐based series to aid clinicians in the preoperative evaluation and postoperative care of patients with lung cancer.

Methods

Since 1953, all newly diagnosed cases of cancer have been required by Norwegian law to be reported to the Cancer Registry of Norway. A total of 26 665 patients were diagnosed with lung cancer in the period 1993–2005. Reports are received from four sources: clinical and pathology reports, the Cause of Death Registry of Statistics Norway and, since 1998, from electronic discharge summaries with diagnosis and procedures for all hospital stays in Norway.

Surgical treatment, defined as any resection of lung tissue with the primary tumour (excluding bronchial resection only), was performed in 4395 patients. Reports were reviewed for all these patients. Additional information about co‐morbidity was collected from patient records in those diagnosed between the years 1993–8. Matching of data was performed using the unique identity numbers given to every citizen at birth or immigration. When a patient underwent a surgical procedure for a second metachronous lung cancer, only the first was included. All cases were evaluated and re‐classified at the Cancer Registry Office according to the pathology tumour‐node‐metastasis (pTNM) classification by an experienced thoracic surgeon (HR).17

In contrast to former publications regarding this population, information from two hospitals was combined because they were both organised under one institution with the same surgeons operating in both places.4,16 Another two hospitals were officially merged in 2004 into one hospital but the location was still geographically different and therefore they were treated as separate units in this series. Surgery for lung cancer was then initially performed in 26 different hospitals. Owing to centralisation, only 17 hospitals treated patients in 2005. Eight hospitals were classified as university hospitals and the remaining were district general hospitals. Hospitals annually operating on an average of ⩾20 patients per year were classified as high‐volume hospitals. Six of the eight university hospitals and two of the 18 district general hospitals were classified as high‐volume. Procedures were performed by general or cardiothoracic surgeons in the period.

Thirty‐day postoperative mortality was defined as death within 30 days of the surgical procedure. Tumour size (largest diameter) was recorded according to measurements by the pathologist. All patients diagnosed from 1993 to 1998 (n = 1851) were selected for scoring according to the CCI, based on information collected from the patient medical records.18 These records could not be retrieved for seven patients, leaving 1844 patients for analysis. The CCI was modified by scoring all forms of previous history of coronary artery disease (myocardial infarction, angina, coronary artery bypass grafting, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty) with a value of 1.5 Hypertension and basal cell carcinoma were not classified as co‐morbidity.

Statistics

Univariate analyses were performed with independent sample t tests and Pearson χ2 statistics including the χ2 test for trend. Multivariate analyses were performed with multiple logistic regression models and goodness of fit tested with the Hosmer‐Lemeshow test.19 All variables considered important before the start of the study were included in the multivariate model, independent of their statistical significance. These were sex, age (as a categorical variable), side of resection, tumour stage according to pTNM, histopathology type, surgical procedure and approach (open thoracotomy or video assisted thoracic surgery), treatment volume of treating hospital and tumour size. Grouping of variables was determined a priori on the basis of clinical relevance, practical classification or definitions used in other studies. The year of diagnosis was tested as a continuous variable and resection margin as a categorical variable but they were not included in the full predictive model because these coefficients would not be available for clinicians in a prospective setting.

For the subset of patients where co‐morbidity was known, we completed a separate analysis with the above listed covariates both with and without the CCI score variable.

Multivariate analysis of individual hospitals was performed by defining a dummy variable for each hospital and successively entering these variables into a logistic regression model containing the significant covariates. To minimise the risks of multiple testing, 99% confidence intervals (CI) were used. The statistical software SPSS Version 12.0 was used for all analyses.

Predictive model

The probability of postoperative death (p) for a single patient is calculated using the formula ln(p/(1 − p)) = total risk score. The total risk score is obtained by adding the appropriate coefficients (β) to the intercept. We calculated this probability for every patient.

Results

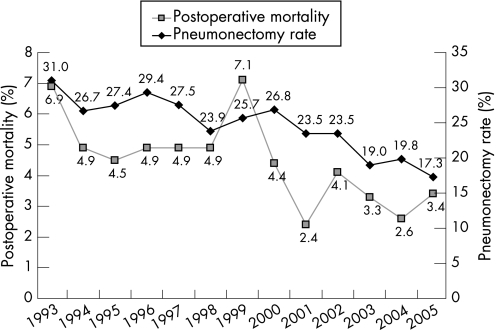

The overall postoperative mortality rate within 30 days was 4.4%. The study group comprised 1647 women and 2748 men (63%, table 1). In the study period the annual postoperative mortality rate varied between 2.4% and 7.1% within 30 days, with improvements in recent years (p for trend = 0.003, fig 1). More than one third of patients were aged ⩾70 years. The histopathology group “other” included 72 patients with small cell lung cancer, of whom only one patient died within 30 days. Two hundred and two patients had a carcinoid tumour and 300 had large cell carcinoma, with postoperative mortality rates of 0.5% and 6.3%, respectively. The remaining 391 tumours were described by the pathologist as carcinoma with no further specification of type. Of the 93 patients with pathological stage IV disease, 77 (83%) had synchronous tumours in other lobe(s).

Table 1 Univariate and multivariate analysis of 30‐day mortality in patients resected for lung cancer 1993–2005 (n = 4395).

| No | Mortality | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | β | ||

| Intercept | −5.97 | ||||||

| Sex | <0.001 | 0.003 | |||||

| Female | 1647 | 41 (2.5) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Male | 2748 | 152 (5.5) | 2.29 (1.62 to 3.26) | 1.76 (1.22 to 2.54) | 0.56 | ||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| <50 | 380 | 9 (2.4) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| 50–59 | 924 | 22 (2.4) | 1.01 (0.50 to 2.20) | 1.04 (0.47 to 2.30) | 0.038 | ||

| 60–69 | 1487 | 51 (3.4) | 1.46 (0.71 to 3.00) | 1.59 (0.77 to 3.30) | 0.47 | ||

| 70–79 | 1471 | 93 (6.3) | 2.78 (1.39 to 5.57) | 3.38 (1.66 to 6.89) | 1.22 | ||

| 80–89 | 133 | 18 (13.5) | 6.45 (2.82 to 14.75) | 9.94 (4.17 to 23.69) | 2.30 | ||

| Side of resection | <0.001 | 0.001 | |||||

| Left | 1991 | 63 (3.2) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Right | 2404 | 130 (5.4) | 1.75 (1.29 to 2.38) | 1.73 (1.24 to 2.41) | 0.55 | ||

| Surgical approach | 0.12 | 0.39 | |||||

| VATS | 132 | 2 (1.5) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Open thoracotomy | 4263 | 191 (4.5) | 3.05 (0.75 to 12.41) | 1.88 (0.44 to 7.97) | 0.63 | ||

| Surgical procedure | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Upper lobectomy | 1520 | 30 (2.0) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Middle lobectomy | 124 | 2 (1.6) | 0.82 (0.19 to 3.46) | 0.61 (0.14 to 2.61) | −0.50 | ||

| Lower lobectomy | 1019 | 35 (3.4) | 1.72 (1.05 to 2.83) | 1.52 (0.92 to 2.52) | 0.42 | ||

| Bilobectomy | 383 | 28 (7.3) | 3.92 (2.31 to 6.65) | 3.06 (1.76 to 5.34) | 1.12 | ||

| Pneumonectomy | 1071 | 92 (8.6) | 4.66 (3.06 to 7.10) | 4.54 (2.87 to 7.18) | 1.51 | ||

| Sublobar resection | 278 | 6 (2.2) | 1.14 (0.47 to 2.76) | 0.92 (0.37 to 2.26) | −0.086 | ||

| Histopathology type | 0.025 | 0.27 | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1865 | 64 (3.4) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Squamous cell | 1565 | 83 (5.3) | 1.58 (1.13 to 2.20) | 1.08 (0.75 to 1.55) | 0.078 | ||

| Other | 965 | 46 (4.8) | 1.41 (0.96 to 2.07) | 1.38 (0.92 to 2.08) | 0.32 | ||

| Pathological stage | <0.001 | 0.066 | |||||

| I | 2856 | 103 (3.6) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| II | 1018 | 54 (5.3) | 1.50 (1.07 to 2.10) | 1.15 (0.81 to 1.65) | 0.14 | ||

| III | 428 | 25 (5.8) | 1.66 (1.06 to 2.60) | 1.24 (0.77 to 2.00) | 0.21 | ||

| IV | 93 | 11 (11.8) | 3.59 (1.85 to 6.93) | 2.67 (1.29 to 5.54) | 0.98 | ||

| Hospital volume | 0.053 | 0.076 | |||||

| <20 | 1476 | 77 (5.2) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| ⩾20 | 2919 | 116 (4.0) | 0.75 (0.56 to 1.00) | 0.76 (0.56 to 1.03) | −0.28 | ||

| Tumour size (cm) | 0.002 | 0.84 | |||||

| ⩽3 | 1877 | 61 (3.2) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| >3–5 | 1409 | 62 (4.4) | 1.37 (0.96 to 1.97) | 0.93 (0.64 to 1.36) | −0.073 | ||

| >5 | 1043 | 66 (6.3) | 2.01 (1.41 to 2.87) | 1.10 (0.74 to 1.62) | 0.095 | ||

| Unknown | 66 | 4 (6.1) | 1.92 (0.68 to 5.45) | 1.16 (0.39 to 3.40) | 0.14 | ||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; β, coefficient beta; VATS, video assisted thoracic surgery.

Figure 1 Annual 30‐day postoperative mortality rate after surgery and pneumonectomy rate in patients with lung cancer diagnosed 1993–2005.

More women than men had adenocarcinomas (46% vs 34%, p<0.001) and fewer women than men had squamous cell carcinoma (23% vs 43%, p<0.001). Women were generally younger at the time of surgery than men (mean age 63.0 vs 65.1 years, p<0.001) and the mean tumour size was smaller in women than in men (3.8 vs 4.3 cm, p<0.001). The proportion of pneumonectomies performed was 19% in women and 28% in men (p<0.001). During the period of investigation the overall pneumonectomy rate decreased from 31% to 17% (p for trend = 0.003, fig 1). However, the annual postoperative mortality after pneumonectomy in the period did not decrease (p for trend = 0.43) while the postoperative mortality for all other procedures decreased (p for trend = 0.012).

Of 1851 patients diagnosed in the period 1993–8, co‐morbidity information was known for 1844 (table 2). Absence of co‐morbid conditions was more common in women than in men (59% vs 47%, p<0.001). For patients with severe co‐morbidity, lobectomy or sublobar resection was the preferred procedure; pneumonectomies were more often performed in patients with no or mild co‐morbidity (table 3). The distribution of patients with co‐morbidity did not differ between low‐volume and high‐volume hospitals, with 50% and 52% of the patients having a CCI score of 0 and 43% and 42% having a CCI score of 1, respectively (p = 0.89).

Table 2 Prevalence of co‐morbid diseases based on the Charlson co‐morbidity index (CCI) in 1844 surgical patients in the period 1993–8.

| CCI score | Condition | No (%) of patients |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coronary artery disease* | 359 (19.5) |

| Congestive heart failure | 61 (3.3) | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 328 (17.8) | |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 143 (7.8) | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 126 (6.8) | |

| Mild liver disease | 8 (0.4) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 53 (2.9) | |

| Connective tissue disease | 3 (0.2) | |

| Diabetes | 70 (3.8) | |

| Dementia | 0 (0) | |

| 2 | Hemiplegia | 10 (0.5) |

| Moderate to severe renal disease | 11 (0.6) | |

| Diabetes with end organ damage | 0 (0) | |

| Any prior tumour within 5 years† | 95 (5.2) | |

| Leukaemia | 2 (0.1) | |

| Lymphoma | 15 (0.8) | |

| 3 | Moderate to severe liver disease | 3 (0.2) |

| 6 | Metastatic solid tumour | 7 (0.4) |

| AIDS | 0 (0) |

*Including myocardial infarction and angina pectoris.

†Excluding basal cell skin carcinoma.

Table 3 Association between co‐morbidity and type of surgery for patients diagnosed 1993–8 (n = 1844).

| Charlson co‐morbidity index (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1–2 | 3–4 | 5+ | |

| Lobectomy | 506 (47.8) | 471 (44.5) | 71 (6.7) | 10 (0.9) |

| Bilobectomy | 93 (53.8) | 71 (41.0) | 8 (4.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Pneumonectomy | 298 (58.9) | 190 (37.5) | 17 (3.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Sublobar resection | 48 (44.9) | 47 (43.9) | 11 (10.3) | 1 (0.9) |

| Total | 945 (51.2) | 779 (42.2) | 107 (5.8) | 13 (0.7) |

Risk factors for postoperative mortality

Univariate analysis of the entire patient cohort (n = 4395) identified significantly higher postoperative mortality in men, elderly patients, those with surgery on the right lung, patients who underwent a lower lobectomy, bilobectomy or pneumonectomy procedure, those with squamous cell carcinoma and cases with disease in advanced pathological stage and larger tumour size (table 1). Pneumonectomy of the right lung was associated with a high risk, especially in those >70 years of age (table 4). Postoperative mortality was higher for right‐sided lobectomies than for left‐sided lobectomies (3.1% vs 1.9%, p = 0.069). The mean 30‐day postoperative mortality in the university hospitals was 3.9% compared with 5.0% in district general hospitals (p = 0.065). The postoperative mortality was significantly higher in the 236 patients where the resection margin was involved than in the 4127 patients where the tumour was completely removed (8.9% vs 4.1%, p = 0.001). Information on this variable was missing for 32 patients.

Table 4 Mortality within 30 days of surgery by age and sex.

| Resection type | Side | <70 years | ⩾70 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Died | % | N | Died | % | ||

| Women | |||||||

| Lobectomy or sublobar resection | Right | 415 | 3 | 0.7 | 214 | 5 | 2.3 |

| Left | 366 | 2 | 0.5 | 199 | 2 | 1.0 | |

| Bilobectomy | 98 | 4 | 4.1 | 48 | 3 | 6.3 | |

| Pneumonectomy | Right | 95 | 10 | 10.5 | 23 | 4 | 17.4 |

| Left | 158 | 6 | 3.8 | 31 | 2 | 6.5 | |

| Total | 1132 | 25 | 2.2 | 515 | 16 | 3.1 | |

| Men | |||||||

| Lobectomy or sublobar resection | Right | 524 | 11 | 2.1 | 381 | 26 | 6.8 |

| Left | 461 | 6 | 1.3 | 381 | 18 | 4.7 | |

| Bilobectomy | 145 | 10 | 6.9 | 92 | 11 | 12.0 | |

| Pneumonectomy | Right | 251 | 18 | 7.2 | 118 | 25 | 21.2 |

| Left | 278 | 12 | 4.3 | 117 | 15 | 12.8 | |

| Total | 1659 | 57 | 3.4 | 1089 | 95 | 8.7 | |

According to multivariate analysis, male sex, older age, surgery on the right lung and a more extensive procedure were significantly associated with postoperative mortality (table 1). The goodness of fit of the model was adequate (p = 0.93). The odds ratio (OR) for involved resection margin compared with free margin was calculated to be 1.80 (p = 0.064) when included as a covariate in the full model. Newer diagnostic year measured as a continuous variable was, however, associated with lower postoperative mortality (p = 0.018, OR 0.95). The separate addition of these two variables did not change the estimates of the other covariates to a significant extent.

In a subset of 1844 patients for whom co‐morbidity was known, the postoperative mortality rate increased from 3.8% for patients without co‐morbid conditions to 5.8%, 10.3% and 15.4% for patients with CCI scores of 1–2, 3–4 and ⩾5, respectively. Only 6.5% of patients had a CCI score of 3 or higher. In multivariate analysis of this subset, CCI was identified as a prognostic factor with a minimal impact on the estimates of other risk factors (table 5).

Table 5 Multivariate analysis of 30‐day mortality in patients resected for lung cancer in 1993–8 (n = 1844), with and without Charlson co‐morbidity index (CCI) score.

| No | Without co‐morbidity data | With co‐morbidity data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | ||

| Sex | 0.022 | 0.039 | |||

| Female | 609 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Male | 1235 | 1.96 (1.10 to 3.48) | 1.84 (1.03 to 3.30) | ||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| <50 | 191 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| 50–59 | 353 | 2.02 (0.62 to 6.53) | 1.82 (0.56 to 5.94) | ||

| 60–69 | 676 | 1.93 (0.64 to 5.82) | 1.63 (0.53 to 5.00) | ||

| 70–79 | 588 | 6.05 (2.07 to 17.68) | 4.91 (1.64 to 14.74) | ||

| 80–89 | 36 | 23.35 (5.74 to 95.08) | 19.71 (4.77 to 81.45) | ||

| Side of resection | 0.009 | 0.012 | |||

| Left | 834 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Right | 1010 | 1.95 (1.18 to 3.23) | 1.91 (1.15 to 3.17) | ||

| Surgical approach | 0.70 | 0.81 | |||

| VATS | 34 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Open thoracotomy | 1810 | 0.67 (0.085 to 5.29) | 0.77 (0.093 to 6.39) | ||

| Surgical procedure | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Upper lobectomy | 597 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Middle lobectomy | 52 | 1.54 (0.31 to 7.59) | 1.78 (0.36 to 8.85) | ||

| Lower lobectomy | 409 | 3.00 (1.36 to 6.64) | 3.05 (1.36 to 6.81) | ||

| Bilobectomy | 173 | 4.33 (1.83 to 10.25) | 4.68 (1.95 to 11.20) | ||

| Pneumonectomy | 506 | 5.90 (2.77 to 12.59) | 6.49 (3.00 to 14.06) | ||

| Sublobar resection | 107 | 0.72 (0.15 to 3.46) | 0.71 (0.15 to 3.44) | ||

| Histopathology type | 0.005 | 0.007 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 700 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Squamous cell | 716 | 1.31 (0.73 to 2.34) | 1.34 (0.75 to 2.40) | ||

| Other | 428 | 2.54 (1.39 to 4.63) | 2.52 (1.37 to 4.64) | ||

| Pathological stage | 0.003 | 0.003 | |||

| I | 1196 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| II | 440 | 1.36 (0.80 to 2.31) | 1.36 (0.80 to 2.31) | ||

| III | 171 | 1.68 (0.82 to 3.47) | 1.66 (0.80 to 3.45) | ||

| IV | 37 | 6.66 (2.43 to 18.28) | 6.83 (2.48 to 18.82) | ||

| Hospital volume | 0.12 | 0.15 | |||

| <20 | 755 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| ⩾20 | 1089 | 0.70 (0.45 to 1.10) | 0.72 (0.46 to 1.12) | ||

| Tumour size (cm) | 0.57 | 0.56 | |||

| ⩽3 | 767 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| >3–5 | 608 | 0.72 (0.42 to 1.23) | 0.69 (0.40 to 1.19) | ||

| >5 | 434 | 0.69 (0.39 to 1.23) | 0.73 (0.41 to 1.30) | ||

| Unknown | 35 | – | – | ||

| CCI | 0.024 | ||||

| 0 | 945 | – | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| 1–2 | 779 | – | 1.39 (0.85 to 2.28) | ||

| 3–4 | 107 | – | 2.48 (1.12 to 5.45) | ||

| ⩾5 | 13 | – | 7.68 (1.39 to 42.45) | ||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; VATS, video assisted thoracic surgery; CCI, Charlson co‐morbidity index.

There was a small discrepancy when comparing the model for all patients and the subset of 1844 patients without the CCI variable (tables 1 and 5). The most important difference was that pathological stage and histopathological type had a significant effect in the subset analysis which was lost in the model for all resected patients.

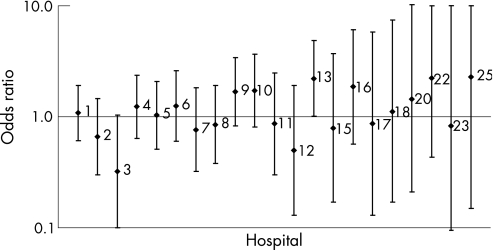

Variation between hospitals with regard to postoperative mortality was assessed in separate multivariate analyses and adjusted for significant covariates (fig 2 and table 6). ORs varied between 0.32 (p = 0.012, 99% CI 0.10 to 1.04) and 2.28 (p = 0.44, 99% CI 0.15 to 34.86). No events of postoperative mortality were observed in five hospitals treating a total of 190 patients.

Figure 2 Odds ratios for individual hospitals with regard to 30‐day postoperative mortality after surgery for lung cancer adjusted for sex, age, side of resection and surgical procedure. 99% CI indicated by vertical bars. Only hospitals with events were included. The hospitals were sorted by hospital treatment volume with the largest first.

Table 6 Odds ratios (ORs) and 99% confidence interval (CI) for individual hospitals with regard to 30‐day postoperative mortality after surgery for lung cancer.

| Hospital | N | Postoperative mortality n (%) | OR (99% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 597 | 26 (4.4) | 1.09 (0.61 to 1.92) | 0.71 |

| 2 | 418 | 12 (2.9) | 0.66 (0.30 to 1.46) | 0.18 |

| 3 | 373 | 5 (1.3) | 0.32 (0.10 to 1.04) | 0.012 |

| 4 | 358 | 20 (5.6) | 1.24 (0.64 to 2.37) | 0.40 |

| 5 | 344 | 16 (4.7) | 1.03 (0.51 to 2.09) | 0.92 |

| 6 | 289 | 15 (5.2) | 1.25 (0.60 to 2.60) | 0.44 |

| 7 | 280 | 10 (3.6) | 0.76 (0.32 to 1.82) | 0.42 |

| 8 | 260 | 12 (4.6) | 0.85 (0.38 to 1.92) | 0.61 |

| 9 | 233 | 17 (7.3) | 1.68 (0.83 to 3.41) | 0.058 |

| 10 | 216 | 15 (6.9) | 1.73 (0.81 to 3.66) | 0.061 |

| 11 | 165 | 7 (4.2) | 0.87 (0.30 to 2.47) | 0.72 |

| 12 | 155 | 4 (2.6) | 0.50 (0.13 to 1.92) | 0.18 |

| 13 | 148 | 14 (9.5) | 2.21 (1.01 to 4.84) | 0.010 |

| 14 | 103 | 0 (0) | − | – |

| 15 | 98 | 3 (3.1) | 0.79 (0.17 to 3.72) | 0.69 |

| 16 | 68 | 6 (8.8) | 1.86 (0.57 to 6.12) | 0.18 |

| 17 | 57 | 2 (3.5) | 0.87 (0.13 to 5.83) | 0.85 |

| 18 | 54 | 2 (3.7) | 1.11 (0.17 to 7.42) | 0.89 |

| 19 | 38 | 0 (0) | − | – |

| 20 | 34 | 2 (5.9) | 1.45 (0.21 to 10.24) | 0.63 |

| 21 | 29 | 0 (0) | − | – |

| 22 | 25 | 3 (12.0) | 2.23 (0.43 to 11.55) | 0.21 |

| 23 | 20 | 1 (5.0) | 0.83 (0.06 to 12.41) | 0.86 |

| 24 | 19 | 0 (0) | − | – |

| 25 | 13 | 1 (7.7) | 2.28 (0.15 to 34.86) | 0.44 |

| 26 | 1 | 0 (0) | − | – |

Adjusted for sex, age, side of resection and surgical procedure.

Risk of dying after surgery: prediction model

Using the prediction model with coefficients from the multivariate analysis, the risk of postoperative mortality for a female patient (β = 0, reference) aged 65 (β = 0.470) undergoing an open (β = 0.630) left (β = 0, reference) lower lobectomy (β = 0.420) for an adenocarcinoma (β = 0, reference) in stage II (β = 0.140) with a diameter of 4 cm (β = −0.074) in a low‐volume hospital (β = 0, reference) would be Σβ = (−5.970+0.470+0.630+0.420+0.140–0.074) = −4.384. The risk of postoperative mortality would be calculated as exp(−4.384)/(1+exp(−4.384)) = 0.012 or 1.2%.

The patient with the highest score was a man aged 83 with adenocarcinoma in pathological stage IV and primary tumour diameter 4.0 cm who underwent an open thoracotomy and right‐sided pneumonectomy at a high‐volume hospital (⩾20 operations/year). He had a preoperative risk score of 0.21 which corresponds to an expected risk of 55%. A total of 88 patients had a preoperative risk score of >20%.

Discussion

This study shows that postoperative mortality in a population‐based setting has decreased some 2% in the most recent time period and there were differences in mortality among hospitals (range 0–12%). Previously identified risk factors for early death from other studies were confirmed. Higher hospital volume (⩾20 operations/year) was associated with a decreased risk of postoperative mortality (OR 0.76) but was not statistically significant (p = 0.076). This study also provides a detailed prediction model for the risk of surgery given preoperative risk factors. Although a preoperative risk score cannot give a precise estimate of the risk for an individual patient, it may be of help in discussing treatment alternatives with the patient and high‐risk patients may be identified in order to provide special postoperative care. Co‐morbidity scored as CCI was identified as an independent risk factor and can be compared with the risk imposed by older age or a larger surgical procedure.

According to previous literature, postoperative mortality varies in different parts of the world. In Australia the overall postoperative mortality was 6% in 1996 in a population‐based cohort (n = 132),15 and in Japan a rate of 0.6% (n = 3270) was reported.13 In a study of a defined population in a region of Sweden (n = 616), the overall postoperative mortality was 2.9% (including exploratory thoracotomies) with a pneumonectomy rate of 26%.14 In the USA the American College of Surgeons has reported an overall postoperative mortality of 4.1% (n = 11 668).20 The decreasing proportion of pneumonectomies can only partially explain the decrease in postoperative mortality over the study period. Postoperative mortality improved considerably for smaller resections, but it is unknown whether this resulted from improvements in surgical technique or changes in postoperative care. A positive trend with lower postoperative mortality in recent diagnostic years was also supported in multivariate analysis.

The strength of this study is the size and quality of the dataset, which includes all patients operated in an entire country with access to extensive and detailed information from different overlapping sources. The selection bias was minimal and the information for each patient was adequate and detailed. A weakness is the lack of information on co‐morbidity for the last period (1999–2005). However, the patients included in this study were all considered fit for surgery and interpretation of prognostic factors and use of the preoperative risk score is only valid under such conditions.

Several previous studies have reported prognostic factors for complications after lung resection. In most of these studies, older age, extent of resection and cardiopulmonary co‐morbidity were related to morbidity or mortality.21 Sex differences have been identified as a prognostic factor both for short‐term and long‐term survival in some series, although a study from France recently suggested that women generally were of younger age, had less co‐morbidity and smoked less, which could explain their superior survival rates.22 In the present series the women were generally younger, had smaller tumours and fewer pneumonectomies and co‐morbidities. Even after adjusting for these factors, we found that women had a significantly better postoperative outcome than men, a finding that we also reported for 5‐year survival after surgery (56% vs 41%).4 Also, in patients with lung cancer in general, regardless of treatment, there is an overall difference in survival between women and men (13% vs 9%).3

Postoperative mortality after bilobectomy and pneumonectomy was high, particularly for right‐sided tumours and elderly patients (⩾70 years). Even in these high‐risk groups, surgery may be warranted because the long‐term prognosis is fairly good provided the patients survive the postoperative period.4,23,24 Sublobar resections could be considered in patients with a major co‐morbidity at the risk of incomplete resection and postoperative mortality that is still fairly high.

Several variables considered to be of significant importance for postoperative mortality were not confirmed as such in multivariate analysis of all patients. The effect of larger tumour size in univariate analysis could be due to an association with more extensive procedures. Increasing pathological stage was associated with a higher risk but was only significant in the subset of patients diagnosed in 1993–8. In the analysis of all patients the OR was considerable lower, especially for those with pathological stage IV. The period effect observed during recent years may have specifically influenced the risk for patients in advanced stages.

In Norway, as in other countries, lung cancer surgery is being centralised to high‐volume hospitals despite the fact that the impact of hospital volume is still debated.25,26 This study could not corroborate a significant effect of hospital volume on postoperative mortality, although the OR at high‐volume hospitals was more favourable. It could be suggested that low‐volume hospitals refer complicated cases to higher volume hospitals which, in most cases, are university hospitals. However, even within the high‐volume group, mortality varied between hospitals and aberrant results were only observed for one of the 26 institutions. Strict confidence intervals of 99% were used to avoid misinterpretation, which is likely to occur when several institutions—some of which had only a few patients—are analysed in this way.24 Furthermore, in the subset of patients with information on co‐morbidity, no difference in co‐morbidity profile was observed between high‐volume and low‐volume hospitals.

The cause of death in patients diagnosed in 1993–2002 is described in detail in a separate paper.16 Pneumonia with respiratory failure, cardiac events, bronchopleural fistula and surgical haemorrhage were the most frequent causes. Some of the patients who died postoperatively in this series were found dead in their bed at the hospital without warning symptoms, indicating another potential for improvement of postoperative care.16

Risk assessment is crucial for those patients at highest risk, and improved intensive postoperative care and observation should be advocated for this group. Several patients had a high calculated preoperative risk for death after surgery, which raises the question of what threshold should patients be excluded for surgery. This is a matter for the patient and the surgeon to discuss, but this risk must be weighed against the alternative treatment modalities with poorer long‐term survival prospects and a considerable risk of treatment‐related morbidity.27,28 A predictive model might aid this discussion.

The prevalence of co‐morbidity in the Norwegian dataset differs from another European study in that patients had less congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease and peripheral vascular disease.5 Also, there were fewer patients with severe co‐morbidity (CCI >2) at 6.5% compared with figures ranging from 9% to 32% in other studies.5,29,30 In Switzerland the mortality has decreased during the last years despite aggravation of cardiopulmonary co‐morbidity in operated patients.31 This study showed that a CCI score of 1–2 increases the postoperative mortality risk by 1.42, which is less than, for example, the impact of sex. For CCI scores of 3–4 the postoperative mortality risk is almost three times higher, but still should not be considered as an absolute contraindication for surgery as this must been seen in relation to other risk factors. Our findings validate the CCI for postoperative mortality and offer the opportunity to weigh the impact of co‐morbidity against other risk factors. Whether patients should be excluded from surgery at a risk estimate of 20%, 30% or 40% is open to debate.

In conclusion, knowledge of risk factors for postoperative death may assist in a more evidence‐based selection of patients for surgery and, more importantly, targeted measures and care may be directed towards those at highest risk of postoperative mortality. Patients should rather be selected for surgery based on an overall evaluation of risk factors, and curative surgical treatment should not be withheld because of co‐morbid conditions or high age alone. There is clearly a potential for improvement in the surgical treatment of lung cancer.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Odd Geiran, Rikshospitalet‐Radiumhospitalet HF, for valuable comments to the manuscript; Bjørn Møller MSc PhD, the Cancer Registry of Norway, for discussion and important contribution to the statistical methods and comments on the manuscript; and the hospitals that were able to provide detailed supplemental information.

Abbreviations

CCI - Charlson co‐morbidity index

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

All patient information for this study was collected according to Norwegian law and statutory regulations, specifically stating that this information should be used for research purposes without patient consent. Ethics committee approval is thus not sought for this kind of studies.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E.et al Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin 200656106–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levi F, Lucchini F, Negri E.et al Mortality from major cancer sites in the European Union, 1955–1998. Ann Oncol 200314490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cancer Registry of Norway Cancer in Norway 2005. 2006. http://www.kreftregisteret.no/forekomst_og_overlevelse_2005/cin2005.pdf

- 4.Strand T E, Rostad H, Moller B.et al Survival after resection for primary lung cancer: a population‐based material of 3211 resected patients. Thorax 200661710–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birim O, Maat A P, Kappetein A P.et al Validation of the Charlson comorbidity index in patients with operated primary non‐small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 20032330–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janssen‐Heijnen M L, Houterman S, Lemmens V E.et al Prognostic impact of increasing age and co‐morbidity in cancer patients: a population‐based approach. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 200555231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colinet B, Jacot W, Bertrand D.et al A new simplified comorbidity score as a prognostic factor in non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients: description and comparison with the Charlson's index. Br J Cancer 2005931098–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birim O, Kappetein A P, Bogers A J. Charlson comorbidity index as a predictor of long‐term outcome after surgery for nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 200528759–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Battafarano R J, Piccirillo J F, Meyers B F.et al Impact of comorbidity on survival after surgical resection in patients with stage I non‐small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002123280–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernard A, Ferrand L, Hagry O.et al Identification of prognostic factors determining risk groups for lung resection. Ann Thorac Surg 2000701161–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson M K, Reeder L B, Mick R. Optimizing selection of patients for major lung resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995109275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harpole D H, Jr, DeCamp M M, Jr, Daley J.et al Prognostic models of thirty‐day mortality and morbidity after major pulmonary resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999117969–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe S, Asamura H, Suzuki K.et al Recent results of postoperative mortality for surgical resections in lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 200478999–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myrdal G, Gustafsson G, Lambe M.et al Outcome after lung cancer surgery. Factors predicting early mortality and major morbidity. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 200120694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mina K, Byrne M J, Ryan G.et al Surgical management of lung cancer in Western Australia in 1996 and its outcomes. Aust NZ J Surg 2004741076–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rostad H, Strand T E, Naalsund A.et al Lung cancer surgery: the first 60 days. A population‐based study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 200629824–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mountain C F. Revisions in the International System for Staging Lung Cancer. Chest 19971111710–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlson M E, Pompei P, Ales K L.et al A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 198740373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosmer D W, Lemeshow S, A goodness of fit test for the multiple logistic regression model Commun Stat. 1980;A9:1043–1069. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little A G, Rusch V W, Bonner J A.et al Patterns of surgical care of lung cancer patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2005802051–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birim O, Kappetein A P, van Klaveren R J.et al Prognostic factors in non‐small cell lung cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 20063212–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foucault C, Berna P, Le Pimpec B F.et al [Lung cancer in women: surgical aspects related to gender]. Rev Mal Respir 200623243–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rostad H, Naalsund A, Strand T E.et al Results of pulmonary resection for lung cancer in Norway, patients older than 70 years. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 200527325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damhuis R, Coonar A, Plaisier P.et al A case‐mix model for monitoring of postoperative mortality after surgery for lung cancer. Lung Cancer 200651123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bach P B, Cramer L D, Schrag D.et al The influence of hospital volume on survival after resection for lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2001345181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freixinet J L, Julia‐Serda G, Rodriguez P M.et al Hospital volume: operative morbidity, mortality and survival in thoracotomy for lung cancer. A Spanish multicenter study of 2994 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 20062920–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeremic B, Classen J, Bamberg M. Radiotherapy alone in technically operable, medically inoperable, early‐stage (I/II) non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 200254119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birim O, Kappetein A P, Goorden T.et al Proper treatment selection may improve survival in patients with clinical early‐stage nonsmall cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2005801021–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Firat S, Bousamra M, Gore E.et al Comorbidity and KPS are independent prognostic factors in stage I non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002521047–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moro‐Sibilot D, Aubert A, Diab S.et al Comorbidities and Charlson score in resected stage I nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur Respir J 200526480–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Licker M J, Widikker I, Robert J.et al Operative mortality and respiratory complications after lung resection for cancer: impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and time trends. Ann Thorac Surg 2006811830–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]