Abstract

Background

It is suggested that the inverse relationship between allergic disease and family size reflects reduced exposure to early life infections, and that antibiotic treatment in childhood diminishes any protective effect of such infection.

Methods

A birth cohort study was undertaken in 642 children recruited before birth and seen annually until the age of 8 years. Reported infections and prescribed antibiotics by the age of 5 years were counted from GP records and comparisons were made with a previous study of their parents.

Results

At the age of 8 years, 104 children (19%) were atopic, 79 (13%) were currently wheezy and 124 (21%) had seasonal rhinitis. 577 children (97%) had at least three infections recorded by age 5, a figure much higher than that of their parents (69%). By the age of 5 only 11 children (2%) had never received a prescription for antibiotics; the corresponding figure for the parents was 24%. Higher numbers of infections were recorded for firstborn children. After adjusting for parental atopy and birth order, there was no association between infection counts and atopy (OR 1.01 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.03) per infection). Significant positive associations were found for wheeze and seasonal rhinitis. An increased risk of current wheeze was found for each antibiotic prescription (adjusted OR 1.07 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.10)) but not for atopy. This was primarily explained by prescriptions for respiratory infections. Similar patterns were observed for seasonal rhinitis.

Conclusions

Despite very high rates of recorded early life infections and antibiotic prescriptions, no plausibly causative relationships were found with subsequent respiratory allergies.

Observing that allergies were less common among “native” Canadians than their “white” counterparts, Gerrard et al1 proposed that “atopic disease is the price paid by some members of the white community… for their relative freedom from diseases due to viruses, bacteria and helminthes”. Thirteen years later Strachan et al2 suggested that the same mechanism might be responsible for the decrease in risk of hay fever with increasing birth order.

Convincing evidence of a general protective effect of infection has, however, remained elusive. In Italy, serological evidence of hepatitis A infection is inversely associated with atopic disease in military recruits,3 a finding that may also be true for other orally‐acquired infections.4 A similar relationship has been observed in the US5,6 but not elsewhere;7,8,9 in any case, it is not clear that an association is independent of a separate birth order effect. Unreplicated studies of infection with measles,10Mycobacterium tuberculosis11 or Schistosoma12 may not be relevant to contemporary European populations, nor is there consistent evidence that treatment with antibiotics in early childhood (which might be expected to diminish any protective effects of infection13) is associated with an increase in the risk of subsequent allergy.14

In 1993 we started to assemble a representative cohort of children born in Ashford, Kent. During this process we observed among their parents, who were born on average 28 years earlier, a strong birth order effect for atopy and allergic respiratory disease. We could not, however, explain this by either documented evidence of common childhood infections or serological evidence of infection with hepatitis A or Helicobacter pylori,8 nor could we measure any association between these outcomes and early life antibiotic prescriptions that was not reasonably explained by reverse causation.15

It may be that the relevant experience of the children in the Ashford cohort was different from that of their parents. Indeed, such a criticism was levelled at our findings relating to childhood antibiotic prescriptions, it being argued that any detrimental effect would be apparent only at the much higher contemporary rates of prescription.16 Here we report the findings from our study of the cohort children, and consider whether changes in infections or antibiotic use across one generation can in any way explain increases in reported allergic disease in the UK.

Methods

In 1993 we started recruitment to a birth cohort by inviting all newly pregnant women presenting to one of three GP surgeries in Ashford, Kent to participate. Details of recruitment and follow‐up are available elsewhere17 but, briefly, 658 mothers (93% of those eligible) agreed to take part and subsequently gave birth to 642 babies. Parental atopy was established at recruitment using skin prick tests in all but three mothers and 542 (87%) of their partners, and asthma or hay fever by self‐report.

Children were visited annually until they were aged 8 years, at which point allergic outcomes were measured. Using standard questions (ISAAC18) administered to parents, we collected information for 92% of the children on wheeze in the past 12 months and on seasonal rhinitis. Seasonal rhinitis was defined as a positive response to the question “In the past 12 months, has your child ever had a problem with sneezing or a runny or blocked nose when s/he did not have a cold or the flu?” along with a record of this occurring in any of the months from March to September inclusive.19 Through skin prick tests (85% of children) we established the presence of atopy, defined by the development of ⩾1 positive response (mean weal 2 mm) to three common allergens (pollen mixture, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and cat fur; ALK, Abelló, UK). We also collected information on family size, current exposure to cigarette smoke and other factors including parental occupational details necessary for allocating children to a social class (Registrar General's 1990 classification, Office for National Statistics). Using father's occupation, social class was categorised as I (professional), II (managerial and technical), IIINM and IIIM (skilled; non‐manual and manual), IV (partly skilled) and V (unskilled).

Three nurses reviewed general practice medical records for 594 (93%) cohort children to the age of 5 years, recording all visits and those for a predetermined list of infections and all antibiotic prescriptions. This was done before establishing the child's allergic status. As with our previous parental analysis, we drew up the following categories of infection: lower respiratory (bronchitis, chest infection, bronchiolitis, pneumonia, cough, wheeze); upper respiratory (upper respiratory tract infection, croup, tracheitis, laryngitis, pharyngitis, sore or septic throat); ear; eye (conjunctivitis); skin (impetigo); urinary tract; and gastrointestinal infections. Infections were considered separate if recorded at consultations ⩾28 days apart. Dates of antibiotic prescriptions were noted and categorised by indication (respiratory, ear, skin, throat, urinary tract, other). Information was only collected for those children for whom we had access to complete medical records.

In 1998 we conducted a retrospective study of the parents of these cohort children to investigate any associations between infections (measured both serologically and counts from GP records) and antibiotic prescriptions in early life with subsequent respiratory allergy in adulthood. The methodology of collecting infection and antibiotic data from the medical records is described in full elsewhere,8,15 but was essentially identical to that for the children as described above.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee and parents/guardians provided signed informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Categories of total infection counts (<25 vs ⩾25 by age 5) and prescribed antibiotics (<15 vs ⩾15 by age 5) were devised which approximately isolated the higher 20% of values. Univariate comparisons were undertaken using χ2 and Mann‐Whitney tests, and tests for trend using χ2 or Cuzick's tests. Adjusted logistic regression was used to examine associations between infection or antibiotic counts and allergic outcomes with results presented as odds per infection, or per antibiotic prescription, as appropriate. Identification of confounders was undertaken using a stepwise approach; all factors detailed in table 1 were considered for inclusion and contributions to the base models were evaluated using changes in log likelihood. Any potential confounder which was significantly associated with any outcome was included in all multivariate models. All analyses were repeated separately for firstborn children (n = 270; 42%) in order to minimise any potential behavioural bias. We also repeated the analysis of lower respiratory infections after excluding “cough” and “wheeze”. Analyses were completed using SAS (Cary, North Carolina, USA) and Stata (College Station, Texas, USA).

Table 1 Sociodemographic associations with allergic outcomes at age 8 in cohort children.

| n | Atopy at age 8 | Current wheeze at age 8 | Seasonal rhinitis at age 8 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | p Value | N (%) | p Value | n (%) | p Value | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 299 | 44 (17.3) | 0.34 | 34 (12.6) | 0.61 | 49 (18.1) | 0.12 |

| Male | 342 | 60 (20.5) | 45 (14.0) | 75 (23.3) | |||

| Maternal atopy | 68 (17.4) | 0.004 | |||||

| – | 423 | 55 (15.2) | 0.002 | 48 (12.3) | 0.30 | ||

| + | 216 | 49 (26.5) | 31 (15.4) | 56 (27.7) | |||

| Paternal atopy | |||||||

| – | 329 | 46 (15.7) | 0.01 | 33 (10.6) | 0.02 | 63 (20.2) | 0.26 |

| + | 230 | 51 (25.3) | 39 (17.6) | 54 (24.3) | |||

| Social class† | |||||||

| I/II | 163 | 28 (19.6) | 0.90* | 22 (13.8) | 0.55* | 39 (24.4) | 0.80* |

| III | 274 | 37 (18.3) | 27 (10.8) | 42 (16.7) | |||

| IV/V | 126 | 16 (14.0) | 20 (16.8) | 32 (26.9) | |||

| Birth order | |||||||

| 1 | 270 | 51 (22.0) | 0.07* | 35 (13.9) | 0.77* | 71 (28.2) | 0.01* |

| 2 | 236 | 37 (18.3) | 28 (12.8) | 30 (13.8) | |||

| 3+ | 136 | 16 (14.0) | 16 (13.0) | 23 (18.7) | |||

| Smoker in the home | |||||||

| No | 373 | 64 (18.6) | 0.77 | 39 (10.5) | 0.01 | 79 (21.2) | 0.86 |

| Yes | 219 | 40 (19.6) | 40 (18.3) | 45 (20.6) | |||

*p for trend.

†Social class defined as I (professional), II (managerial and technical), III (skilled), IV (partly skilled), V (unskilled).

Results

Infection counts and antibiotic prescriptions: parents vs children

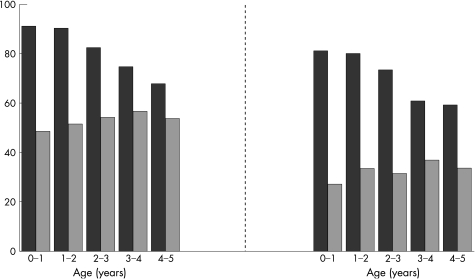

Both infection counts and antibiotic prescriptions were higher for the children than their parents, particularly in the first 2 years of life (fig 1). The median number of infections recorded in the medical records up to age 5 was 14 (range 0–71) for the children and 5 (0–50) for their parents. By that age, only three children (0.5%) but 7% of parents had none recorded. Among the children, upper and lower respiratory infections were most common (at least one in the first 5 years, 94% each), followed by ear (80%), eye (65%), gastrointestinal (63%), urinary tract (15%) and skin infections (15%). The corresponding figures for parents were: upper respiratory (65%), lower respiratory (56%), ear (33%), eye (27%), gastrointestinal (28%), urinary tract (9%) and skin (45%).

Figure 1 Proportion of participants with ⩾1 infection recorded by year of age (left graph: black bars, children; grey bars, parents) and proportion of participants with ⩾1 antibiotic prescription by year of age (right graph: black bars, children; grey bars, parents).

Antibiotics were prescribed more frequently and at an earlier age for the children. The median number of prescriptions up to age 5 was 9 (range 0–45) compared with 2 (0–31) for their parents; and the median age at first prescription was 5.0 months (range 2 days to 4.9 years) compared with 18.1 months (range 0–5 years) for their parents. By the age of 5, only 11 children (2%) but 24% of parents had never received an antibiotic prescription.

Atopy and allergic outcomes: cohort children

At the age of 8 years 104 children (19%) were designated as having atopy, 79 (13%) were reported to have had wheeze in the past 12 months and 124 (21%) to have seasonal rhinitis. There were no differences in these proportions according to sex (table 1) or social class, with the exception of seasonal rhinitis which was less prevalent among those in social class III (p = 0.04), although this did not follow a linear trend (ptrend = 0.80). Children of mothers or fathers with atopy were more likely to be atopic or to have wheeze or seasonal rhinitis. Atopy (ptrend = 0.07) and seasonal rhinitis (ptrend = 0.01), but not current wheeze (ptrend = 0.77), were related inversely to birth order. There were no differences in any outcomes between children registered with different practices.

Recorded infections: cohort children

Doctors in one practice recorded higher rates of infection than the other two (median 17 vs 12 and 13; p<0.001); they also wrote the highest number of antibiotic prescriptions (median 11 vs 7 and 9; p<0.001).

Among the children, the median age at first recorded infection was 3.9 months (range 0 days to 4.9 years). Firstborn children were more likely to be older at the point of first recorded infection (median age 4.4 months) than those of higher birth order (3.6 months; p = 0.03). This difference was greatest for lower respiratory infections (8.1 vs 5.7 months; p<0.001) and eye infections (14.1 vs 7.6 months; p<0.001). In contrast, first gastrointestinal infections tended to be reported earlier for firstborn children (11.0 vs 14.1 months; p<0.001). Children of higher birth order and social class were less likely to have ⩾25 infections by age 5 (table 2); there were no important differences between children with and without a parent with atopy.

Table 2 Sociodemographic associations with recorded infections, antibiotic prescriptions and total visits to general practitioner (GP) by age 5 years in cohort children.

| Total | ⩾25 infections by age 5 | ⩾15 prescriptions by age 5 | Total visits to GP by age 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | p Value | n (%) | p Value | Median (range) | p Value | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 299 | 44 (16.0) | 0.28 | 61 (22.2) | 0.94 | 29 (7–107) | 0.02 |

| Male | 342 | 62 (19.4) | 70 (21.9) | 32 (2–151) | |||

| Maternal atopy | |||||||

| – | 232 | 66 (16.9) | 0.40 | 74 (19.0) | 0.02 | 29 (2–124) | 0.004 |

| + | 403 | 40 (19.7) | 56 (27.6) | 34 (5–151) | |||

| Paternal atopy | |||||||

| – | 210 | 54 (17.4) | 0.93 | 72 (23.2) | 0.44 | 32 (2–151) | 0.33 |

| + | 366 | 39 (17.7) | 45 (20.4) | 29 (3–124) | |||

| Social class | |||||||

| I/II | 163 | 24 (15.3) | 0.06* | 33 (21.0) | 0.13* | 32 (5–151) | 0.86* |

| III | 274 | 38 (14.9) | 48 (18.8) | 29 (3–99) | |||

| IV/V | 126 | 29 (24.4) | 35 (29.4) | 32 (6–82) | |||

| Birth order | |||||||

| 1 | 270 | 55 (22.2) | 0.02* | 63 (25.4) | 0.43* | 34 (4–151) | <0.001* |

| 2 | 236 | 35 (15.9) | 38 (17.3) | 28 (2–91) | |||

| 3+ | 136 | 16 (12.7) | 30 (23.8) | 27 (5–107) | |||

| Smoker in the home | |||||||

| No | 373 | 65 (17.8) | 0.98 | 81 (22.1) | 0.94 | 31 (3–151) | 0.73 |

| Yes | 219 | 38 (17.7) | 47 (21.9) | 31 (2–107) | |||

*p for trend.

†Social class defined as I (professional), II (managerial and technical), III (skilled), IV (partly skilled); V (unskilled).

On crude analysis, children who had ⩾25 recorded infections by age 5 were more likely to have wheeze or seasonal rhinitis at age 8 (table 3). After adjustment—with the single exception of infections between ages 4 and 5 years—there were no relationships between infections of any category and atopy at age 8 (table 4). In contrast, there were positive associations between wheeze and infection counts at all ages, which appeared to be confined to lower respiratory and gastrointestinal infections only (p<0.001 and p = 0.01, respectively). The patterns were very similar for seasonal rhinitis, although there were positive associations also with ear and upper respiratory infections. For both wheeze and seasonal rhinitis, the strength of the associations increased with age of recorded infection. There was some evidence of an overlap between these symptoms; 36 (45.6%) of the children who wheezed also had seasonal rhinitis compared with 88 (17.1%) of the children who did not currently have wheeze (p<0.001). However, adjusting the analyses of wheezing for the presence of seasonal rhinitis and vice versa did not have any effect on the final estimates (data not shown).

Table 3 Associations between infection counts and antibiotic prescriptions by age 5 and outcomes at age 8: cohort children.

| Total | ⩾25 infections by age 5 | ⩾15 prescriptions by age 5 | Total visits to GP by age 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | p Value | n (%) | p Value | Median (range) | p Value | ||

| Atopy at age 8 | 0.02 | ||||||

| – | 444 | 78 (17.8) | 0.90 | 94 (21.4) | 0.32 | 31 (3–151) | |

| + | 104 | 19 (18.3) | 27 (26.0) | 35 (2–98) | |||

| Current wheeze at age 8 | <0.001 | ||||||

| – | 514 | 76 (15.1) | <0.001 | 98 (19.4) | <0.001 | 29 (11–124) | |

| + | 79 | 27 (35.1) | 30 (39.0) | 39 (2–151) | |||

| Seasonal rhinitis at age 8 | <0.001 | ||||||

| – | 470 | 67 (14.6) | <0.001 | 85 (18.5) | <0.001 | 29 (2–124) | |

| + | 123 | 36 (29.5) | 43 (35.3) | 39 (8–151) | |||

Table 4 Associations between infection counts by age 5 and outcomes at age 8: cohort children.

| No of infections | Atopy at age 8 (n = 490) | Current wheeze at age 8 (n = 523) | Seasonal rhinitis at age 8 (n = 523) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR* (95% CI) | p Value | OR* (95% CI) | p Value | OR* (95% CI) | p Value | ||

| Total infections age 0–5 | 9526 | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | 0.28 | 1.05 (1.03 to 1.08) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.03 to 1.07) | <0.001 |

| Total infections age 0–1 | 2673 | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.05) | 0.65 | 1.09 (1.02 to 1.17) | 0.01 | 1.06 (1.00 to 1.13) | 0.04 |

| Total infections age 1–2 | 2456 | 0.99 (0.93 to 1.06) | 0.84 | 1.10 (1.02 to 1.18) | 0.01 | 1.10 (1.04 to 1.17) | 0.002 |

| Total infections age 2–3 | 1934 | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.15) | 0.08 | 1.11 (1.02 to 1.21) | 0.02 | 1.12 (1.05 to 1.21) | 0.001 |

| Total infections age 3–4 | 1439 | 1.06 (0.97 to 1.16) | 0.18 | 1.20 (1.09 to 1.31) | <0.001 | 1.24 (1.14 to 1.35) | <0.001 |

| Total infections age 4–5 | 1122 | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.23) | 0.03 | 1.26 (1.13 to 1.39) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.10 to 1.32) | <0.001 |

| Infection type (age 0–5) | |||||||

| Lower respiratory | 3364 | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.07) | 0.20 | 1.14 (1.09 to 1.20) | <0.001 | 1.09 (1.05 to 1.14) | <0.001 |

| Upper respiratory | 3006 | 0.99 (0.93 to 1.06) | 0.86 | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.12) | 0.13 | 1.09 (1.03 to 1.15) | 0.003 |

| Ear | 1462 | 1.03 (0.95 to 1.12) | 0.49 | 1.07 (0.98 to 1.18) | 0.16 | 1.16 (1.07 to 1.25) | <0.001 |

| Eye | 753 | 1.07 (0.92 to 1.23) | 0.40 | 1.17 (1.00 to 1.37) | 0.06 | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.25) | 0.23 |

| Gastrointestinal | 695 | 1.13 (0.96 to 1.33) | 0.14 | 1.23 (1.03 to 1.47) | 0.03 | 1.36 (1.17 to 1.58) | <0.001 |

| Urinary tract | 132 | 0.79 (0.52 to 1.19) | 0.23 | 0.78 (0.49 to 1.25) | 0.27 | 1.01 (0.73 to 1.39) | 0.96 |

| Skin | 114 | 1.30 (0.89 to 1.91) | 0.18 | 0.79 (0.45 to 1.39) | 0.39 | 1.03 (0.69 to 1.54) | 0.87 |

*Adjusted for maternal atopy, paternal atopy, birth order and current exposure to cigarette smoke.

Annual counts of lower respiratory infections were positively associated with current wheeze; adjusted odds ratios increased steadily from 1.16 for infections recorded between birth and age 1 year to 1.17, 1.45, 1.66 and 1.86 for infections recorded at ages 1–2, 2–3, 3–4 and 4–5, respectively. Each of these estimates was statistically significant (p<0.05). We found a similar pattern for upper respiratory infections although the trend was weaker; this was also the case for seasonal rhinitis and both lower and upper respiratory infections (data available). For all outcomes, ORs were identical or slightly higher when “wheeze” and “cough” were omitted from the lower respiratory infection categories (data not shown).

Antibiotic prescriptions: cohort children

Children whose mother had atopy were more likely to be prescribed ⩾15 antibiotic courses by age 5 (table 2). There were small differences by social class (p = 0.07), although these differences were not linear (ptrend = 0.13). No differences were found by birth order. Children with wheeze or seasonal rhinitis at age 8 were significantly more likely to have had more antibiotic prescriptions by age 5 (OR 1.07 and 1.06 respectively per prescription, table 5); there was no such association with atopy. For both wheeze and rhinitis, the relationship was evident at all ages of prescription above 1 year and was stronger and statistically significant only (for the most part) for prescriptions provided for respiratory indications. After excluding children with wheeze at age 1 or 2 years from the analysis (n = 257), none of the associations between antibiotic counts and current wheeze was statistically significant and the effect estimates tended towards the null (data not shown). There were no clear associations between age at first prescription and any outcomes (data available).

Table 5 Associations between antibiotic prescriptions by age 5 and outcomes at age 8: cohort children.

| Total no of prescriptions | Atopy at age 8 (n = 490) | Current wheeze at age 8 (n = 523) | Seasonal rhinitis at age 8 (n = 523) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR* (95% CI) | p Value | OR* (95% CI) | p Value | OR* (95% CI) | p Value | ||

| Total antibiotics age 0–5 | 6150 | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.03) | 0.86 | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.10) | <0.001 | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09) | <0.001 |

| Total antibiotics age 0–1 | 1631 | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.05) | 0.37 | 1.08 (0.98 to 1.19) | 0.13 | 1.08 (1.00 to 1.17) | 0.06 |

| Total antibiotics age 1–2 | 1596 | 0.99 (0.91 to 1.09) | 0.90 | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.27) | 0.001 | 1.10 (1.02 to 1.19) | 0.02 |

| Total antibiotics age 2–3 | 1248 | 1.02 (0.93 to 1.13) | 0.64 | 1.15 (1.04 to 1.28) | 0.01 | 1.11 (1.02 to 1.22) | 0.02 |

| Total antibiotics age 3–4 | 962 | 1.06 (0.94 to 1.19) | 0.36 | 1.27 (1.12 to 1.44) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.13 to 1.40) | <0.001 |

| Total antibiotics age 4–5 | 776 | 1.04 (0.92 to 1.18) | 0.52 | 1.14 (0.99 to 1.30) | 0.07 | 1.18 (1.06 to 1.33) | 0.004 |

| Respiratory infections | |||||||

| Total antibiotics age 0–5 | 2249 | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.07) | 0.81 | 1.15 (1.08 to 1.22) | <0.001 | 1.12 (1.06 to 1.18) | <0.001 |

| Total antibiotics age 0–1 | 731 | 0.91 (0.77 to 1.08) | 0.29 | 1.18 (0.96 to 1.32) | 0.16 | 1.15 (1.00 to 1.32) | 0.06 |

| Total antibiotics age 1–2 | 608 | 0.94 (0.79 to 1.12) | 0.45 | 1.21 (1.03 to 1.42) | 0.02 | 1.19 (1.04 to 1.36) | 0.01 |

| Total antibiotics age 2–3 | 431 | 1.07 (0.88 to 1.31) | 0.49 | 1.43 (1.18 to 1.74) | 0.001 | 1.25 (1.05 to 1.49) | 0.02 |

| Total antibiotics age 3–4 | 315 | 1.23 (1.00 to 1.52) | 0.06 | 1.85 (1.48 to 2.32) | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.27 to 1.92) | <0.001 |

| Total antibiotics age 4–5 | 191 | 1.14 (0.87 to 1.48) | 0.35 | 1.76 (1.32 to 2.36) | <0.001 | 1.54 (1.18 to 2.01) | 0.001 |

| Non‐respiratory infections | |||||||

| Total antibiotics age 0–5 | 3901 | 1.00 (0.96 to 1.05) | 0.94 | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.10) | 0.05 | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.10) | 0.01 |

| Total antibiotics age 0–1 | 900 | 0.97 (0.85 to 1.11) | 0.67 | 1.08 (0.94 to 1.25) | 0.30 | 1.07 (0.95 to 1.21) | 0.26 |

| Total antibiotics age 1–2 | 988 | 1.02 (0.91 to 1.15) | 0.71 | 1.18 (1.05 to 1.33) | 0.01 | 1.08 (0.97 to 1.20) | 0.16 |

| Total antibiotics age 2–3 | 817 | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.15) | 0.87 | 1.08 (0.93 to 1.24) | 0.34 | 1.09 (0.97 to 1.22) | 0.15 |

| Total antibiotics age 3–4 | 647 | 0.99 (0.84 to 1.16) | 0.89 | 1.09 (0.91 to 1.30) | 0.36 | 1.21 (1.05 to 1.40) | 0.01 |

| Total antibiotics age 4–5 | 585 | 1.02 (0.87 to 1.19) | 0.78 | 0.99 (0.82 to 1.18) | 0.88 | 1.13 (0.99 to 1.30) | 0.09 |

*Adjusted for maternal atopy, paternal atopy, birth order and current exposure to cigarette smoke.

We found no evidence of effect modification by pet ownership (OR per antibiotic prescription for those with <2 pets in the first year of life 0.99 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.03) vs 1.03 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.08)), maternal asthma (OR 1.06 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.15) present vs 0.99 (95% CI 0.96 to 1.03) absent) or breast feeding (OR 1.02 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.06) vs 0.98 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.04)).

Infections associated with an antibiotic prescription: cohort children

Almost half of all visits (45.3%) for an infection coincided with an antibiotic prescription for the same reason on the same date. This figure was constant for all ages but varied by indication; only 2.0% of gastrointestinal infections but 86.8% of ear infections resulted in a prescription. Differentiating between infections which were treated by antibiotics and those which were not did not result in any major differences in risk estimates (data not shown).

Number of visits to general practitioner: cohort children

Children made a median of 31 (range 2–151) visits to their GP between birth and the age of 5 years. Boys had a higher number of total visits than girls (table 2), as did those who were firstborn; this last relationship was evident only for visits made after the first year of life (data not shown). Children with current wheeze at the age of 8 accrued a higher number of visits than those without wheeze (median 39 (range 11–124) vs 29 (range 2–151), respectively, p<0.001). These figures were very similar for seasonal rhinitis and there were similar but smaller—albeit still statistically significant—differences between children with and without atopy (table 2).

Stratification by birth order: cohort children

We repeated all of the above analyses for those children with no older siblings (n = 270; 42%). Each of the crude and adjusted risk estimates associated with both recorded infections and antibiotic prescriptions were very similar to those derived from the total cohort (data available).

Discussion

The children in this representative contemporary English birth cohort had far higher numbers of recorded infections and far more antibiotic prescriptions than did their parents. Nonetheless, we were unable to find any evidence among them of protection from subsequent atopy or allergic disease by infection in early life; indeed, children who had either wheeze or seasonal rhinitis at age 8 had a higher number of infections recorded by their GPs; the associations were largely limited to respiratory‐type infections. Similarly, the positive associations with antibiotic prescriptions appeared to be confined to those given for respiratory indications. We also found no evidence of any association between early antibiotic use and wheeze that started after age 3. In these respects, our findings are very similar to those we observed among the cohort parents and are best explained, we believe, by reverse causation.

Our population is relatively small but probably representative. Through the goodwill of the cohort families and their GPs, we have been able to maintain high rates of follow‐up and the associations we report here are likely to be generalisable to other western European populations. Information from medical records was available for almost all children and was collated before establishing their allergic status. In the absence of comparable information, we do not know how our counts of recorded infections compare with other populations in the UK or elsewhere, but the rates of antibiotic prescription may be somewhat higher. In our cohort 81% of children had had at least one antibiotic prescription by the age of 1 year. Comparable proportions reported by Celedon et al20 in their “enriched” cohort and from the UK General Practice Research Database were 71% and 65%, respectively.21 These differences may reflect true variations in medical practice or more accurate ascertainment in our study. In any case, it can scarcely still be argued that any detrimental effect of antibiotic use in early life would only be apparent at high rates of prescription.

The role of antibiotics during childhood remains a contentious issue, however. Since our earlier summary of the literature15 there have been four further publications reporting a positive association between antibiotic prescription and childhood allergy. Two large case‐control studies using UK general practice databases were reported by Bremner et al.22 A pooled OR for hay fever of 1.11 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.20) was found for those children exposed to antibiotics in the first year of life, although this reduced to 0.92 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.00) after adjusting for consultation behaviour. In another study23 1584 children who had been notified to state‐funded health services with a serious infection at age 0–4 years were compared with 2539 children sampled from the general population. In both groups there was an association between antibiotic use in the first year of life and current wheezing at age 6–7 years (OR 1.78 (95% CI 1.49, 2.14)) and asthma ever (OR 2.10 (95% CI 1.79 to 2.48)). The authors acknowledged that the possibility of reverse causation cannot be excluded. In a more recent birth cohort, adjusted estimates of the risk of atopy at age 6–7 were increased (OR 1.48 (95% CI 0.94 to 2.34)),24 although exposures were restricted to any antibiotic exposure in the first 6 months of life compared with none. To the best of our knowledge, this is the only study which has reported a significant association between antibiotic use and atopy where atopy is measured objectively. We were unable to replicate their findings of heightened risk among various subgroups (children with <2 pets in their first year of life, breastfed for ⩾4 months, or with maternal asthma). More recently, a meta‐analysis of eight observational studies investigating the associations between antibiotic exposure in the first year of life and the development of childhood asthma14 reported a significant pooled risk (OR 2.05 (95% CI 1.41 to 2.99)), although only the “retrospective” studies provided a significant pooled association. The authors also acknowledged that some of the papers relied upon self‐reporting and so may be susceptible to bias. No attempt to adjust for indication was made. In addition, an ecological comparison of per capita antibiotic sales with the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis and eczema has been conducted using data from 99 centres in 28 countries.25 Positive relationships were found, although these generally disappeared after adjustment for gross national product. The investigators concluded that, if there was a causal association of antibiotic use with asthma risk, it does not appear to explain the international differences in the prevalence of asthma, and that their findings are generally not consistent with the hypothesis that antibiotic use increases the risk of asthma, rhinitis or eczema. An accompanying commentary26 suggested that the findings give further weight to an explanation of protopathic bias (reverse causation), whereby the increased exposure to antibiotics experienced by individuals with allergic disease is most likely explained by those individuals receiving the antibiotics as treatment for symptoms which were early manifestations of their disease.

For over 20 years it has been widely held that “infections” are protective against childhood allergies. While this may be true in some settings and for some specific infections, it does not appear to be the general case in contemporary English children. In this context, our findings (and those from the cohort parents) are very similar to those reported by McKeever et al,21 although we have used an additional objective outcome (atopy). Both studies used general practice records of early infection. We recognise the important limitations of this approach and acknowledge the certainty that such measurement will be an incomplete reflection of a child's full infectious experience. In addition, there are important and complex variations in healthcare‐seeking behaviour both between and within families; the latter, for example, manifest in our population by the higher number of visits to the GP made on behalf of firstborn children—although, interestingly, only after the first year of life. We also found that firstborn children were more likely to be older at the point of first recorded infection than those of higher birth order, a difference which was particularly evident for lower respiratory infections. We attempted to account for these differences through multivariate adjustment and by stratification; neither approach made any difference to our findings. Medical behaviour, both in diagnosis and prescription, will also vary (as we found), but there were no accompanying differences between general practices and the rates of atopy or parentally‐reported wheeze or rhinitis among the children registered as their patients. While our measures of infection are therefore flawed, we would nonetheless expect to have detected some signal of protection if such an effect exists. Interestingly, one of two studies27 to have reported a protective effect of early infection (“runny nose”) in a contemporary European population used parentally‐remembered (rather than doctor‐recorded) information; in this instance it is difficult to exclude a biased recall. The other study6 reported a reduced risk of atopy ascertained by measurement of specific IgE in serum with increasing number of fevers recorded before age 1 year, although these findings were not replicated for atopy defined by skin test response.

Cohet et al23 reported comparisons between 1584 children notified to state‐funded health services with serious infections aged 0–4 and 2539 children sampled from the general population. No difference in the prevalence of current wheezing (23.5% vs 24.3%) between these groups was found and consideration of the major site of the infection had little effect. However, this analysis was restricted to notifiable infections and the authors acknowledge that it may be inappropriate to extend these findings to childhood infections in general. Our findings are similar to those from a 10 year follow‐up study of the Oslo birth cohort9 where early respiratory infections did not protect against the development of allergic rhinitis or sensitisation and were associated with an increased risk for asthma.

This representative cohort of English children born 10 years ago has had far higher rates of both recorded infections and antibiotic prescriptions than their parents born 35 years earlier. Nonetheless, we have failed to find either a convincing protective effect of general infections or a detrimental effect of antibiotic prescription on the subsequent development of atopy or associated allergic disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the families who have participated in the study and to the general practitioners who granted access to their medical records.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the Colt Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Gerrard J W, Geddes C A, Reggin P L.et al Serum IgE levels in white and metis communities in Saskatchewan. Ann Allergy 19763791–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strachan D P. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ 19892991259–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matricardi P M, Rosmini F, Ferrigno L.et al Cross sectional retrospective study of prevalence of atopy among Italian military students with antibodies against hepatitis A virus. BMJ 1997314999–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matricardi P M, Rosmini F, Riondino S.et al Exposure to foodborne and orofecal microbes versus airborne viruses in relation to atopy and allergic asthma: epidemiological study. BMJ 2000320412–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matricardi P M, Rosmini F, Panetta V.et al Hay fever and asthma in relation to markers of infection in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002110381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams L K, Peterson E L, Ownby D R.et al The relationship between early fever and allergic sensitization at age 6 to 7 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004113291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodner C, Anderson W J, Reid T S.et al Childhood exposure to infection and risk of adult onset wheeze and atopy. Thorax 200055383–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cullinan P, Harris J M, Newman Taylor A J.et al Can early infection explain the sibling effect in adult atopy? Eur Respir J 200322956–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nafstad P, Brunekreef B, Skrondal A.et al Early respiratory infections, asthma, and allergy: 10‐year follow‐up of the Oslo birth cohort. Pediatrics 2005116e255–e262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaheen S O, Aaby P, Hall A J.et al Measles and atopy in Guinea‐Bissau. Lancet 19963471792–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirakawa T, Enomoto T, Shimazu S.et al The inverse association between tuberculin responses and atopic disorder. Science 199727577–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Biggelaar A H, van R R, Rodrigues L C.et al Decreased atopy in children infected with Schistosoma haematobium: a role for parasite‐induced interleukin‐10. Lancet 20003561723–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjorksten B. Effects of intestinal microflora and the environment on the development of asthma and allergy. Springer Seminars in Immunopathology 200425257–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marra F, Lynd L, Coombes M.et al Does antibiotic exposure during infancy lead to development of asthma? : a systematic review and metaanalysis, Chest 2006129610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cullinan P, Harris J, Mills P.et al Early prescriptions of antibiotics and the risk of allergic disease in adults: a cohort study. Thorax 20045911–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas M. Early life antibiotics and asthma. Thorax 200459541. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cullinan P, MacNeill S J, Harris J M.et al Early allergen exposure, skin prick responses, and atopic wheeze at age 5 in English children: a cohort study. Thorax 200459855–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asher M I, Keil U, Anderson H R.et al International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J 19958483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun‐Fahrlander C, Wuthrich B, Gassner M.et al Validation of a rhinitis symptom questionnaire (ISAAC core questions) in a population of Swiss school children visiting the school health services. SCARPOL‐team. Swiss Study on Childhood Allergy and Respiratory Symptom with respect to Air Pollution and Climate. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 1997875–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Celedon J C, Litonjua A A, Ryan L.et al Lack of association between antibiotic use in the first year of life and asthma, allergic rhinitis, or eczema at age 5 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 200216672–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKeever T M, Lewis S A, Smith C.et al Early exposure to infections and antibiotics and the incidence of allergic disease: a birth cohort study with the West Midlands General Practice Research Database. J Allergy Clin Immunol 200210943–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bremner S A, Carey I M, DeWilde S.et al Early‐life exposure to antibacterials and the subsequent development of hayfever in childhood in the UK: case‐control studies using the General Practice Research Database and the Doctors' Independent Network. Clin Exp Allergy 2003331518–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohet C, Cheng S, MacDonald C.et al Infections, medication use, and the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis, and eczema in childhood. J Epidemiol Community Health 200458852–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson C C, Ownby D R, Alford S H.et al Antibiotic exposure in early infancy and risk for childhood atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 20051151218–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foliaki S, Nielsen S K, Bjorksten B.et al Antibiotic sales and the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis, and eczema: The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Int J Epidemiol 200433558–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pekkanen J. Commentary: use of antibiotics and risk of asthma. Int J Epidemiol 200433564–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Illi S, Von M E, Lau S.et al Early childhood infectious diseases and the development of asthma up to school age: a birth cohort study. BMJ 2001322390–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]