Abstract

Background

Airway hyperresponsiveness is the ability of airways to narrow excessively in response to inhaled stimuli and is a key feature of asthma. Airway inflammation and ventilation heterogeneity have been separately shown to be associated with airway hyperresponsiveness. A study was undertaken to establish whether ventilation heterogeneity is associated with airway hyperresponsiveness independently of airway inflammation in subjects with asthma and to determine the effect of inhaled corticosteroids on this relationship.

Methods

Airway inflammation was measured in 40 subjects with asthma by exhaled nitric oxide, ventilation heterogeneity by multiple breath nitrogen washout and airway hyperresponsiveness by methacholine challenge. In 18 of these subjects with uncontrolled symptoms, measurements were repeated after 3 months of treatment with inhaled beclomethasone dipropionate.

Results

At baseline, airway hyperresponsiveness was independently predicted by airway inflammation (partial r2 = 0.20, p<0.001) and ventilation heterogeneity (partial r2 = 0.39, p<0.001). Inhaled corticosteroid treatment decreased airway inflammation (p = 0.002), ventilation heterogeneity (p = 0.009) and airway hyperresponsiveness (p<0.001). After treatment, ventilation heterogeneity was the sole predictor of airway hyperresponsiveness (r2 = 0.64, p<0.001).

Conclusions

Baseline ventilation heterogeneity is a strong predictor of airway hyperresponsiveness, independent of airway inflammation in subjects with asthma. Its persistent relationship with airway hyperresponsiveness following anti‐inflammatory treatment suggests that it is an important independent determinant of airway hyperresponsiveness. Normalisation of ventilation heterogeneity is therefore a potential goal of treatment that may lead to improved long‐term outcomes.

Airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) is a common feature of asthma that is defined as the ability of airways to narrow too easily and by too much in response to provoking stimuli. In subjects with asthma with severe AHR, excessive airway narrowing represents the potential for severe and life‐threatening asthma attacks.1 AHR is a clinically useful tool for treatment monitoring,2 and is associated with impaired development of lung function in childhood.3 Although AHR has been shown to be associated with airway inflammation4 and ventilation heterogeneity,5 the mechanisms that cause AHR are poorly understood.

Although airway inflammation is regarded as the underlying cause of AHR,6 it is not known exactly how inflammation may cause AHR. Significant associations between AHR and markers of eosinophilic inflammation in induced sputum7 and the level of nitric oxide in exhaled breath4 have been observed, but other studies have failed to show any association between airway inflammation and AHR.8,9 Evidence suggests that other non‐eosinophilic pathways such as neutrophilic inflammation are important contributors to AHR and asthma.10 Exhaled nitric oxide is an indirect marker of eosinophilic airway inflammation that is easy to perform, is reduced with anti‐inflammatory inhaled corticosteroid treatment (ICS),2 and is more closely associated with AHR and active asthma than other markers of airway inflammation such as sputum eosinophils4 and serum markers.11 For these reasons, exhaled nitric oxide may be a suitable marker of eosinophilic inflammation to explore the relationship between AHR, airway inflammation and ventilation heterogeneity, and to determine the effect of ICS treatment on this relationship.

Ventilation heterogeneity is another potential cause of AHR.5 Supportive evidence for a causal association arises from computer simulations whereby a more uneven distribution of ventilation and airway narrowing throughout the lung results in a greater overall increase in airway resistance following bronchoconstriction (ie, AHR).12,13,14 Ventilation heterogeneity can be assessed non‐invasively by multiple breath nitrogen washout (MBNW).15 The greater the degree of ventilation heterogeneity within the lung during continuous tidal breathing of 100% oxygen, the greater the nitrogen phase III slope in each subsequent MBNW expiration. More specifically, the phase III slope is determined by convective gas transport, predominantly in the conductive airways, and by diffusive transport in the more peripheral acinar airways. From multiple breath washout tests using inert gases with different diffusivities,16 SF6 and helium, it has been possible to partition the convection from the diffusion‐dependent portion of the phase III slope, and derive corresponding indices of conductive airway heterogeneity (Scond) and acinar heterogeneity (Sacin). The value of these indices increases as ventilation heterogeneity in the corresponding lung zone increases. The mathematical derivation of these indices is explained in the online supplement available at http://thorax.bmj.com/supplemental. Using this MBNW analysis, ventilation heterogeneity in conductive and acinar lung zones has been shown to be abnormal in asthma17 and to be more sensitive than spirometry for detecting early changes to the peripheral airways associated with cigarette smoking.15

We hypothesised that there would be an association between ventilation heterogeneity and AHR and have tested whether this association is independent of airway inflammation in a cross‐sectional study of subjects with asthma of a wide range of severity. In a subgroup of these subjects with clinically uncontrolled asthma, we further tested the relationship between airway inflammation, ventilation heterogeneity and AHR following 3 months of treatment with ICS.

Methods

Study design

Subjects in whom asthma had been diagnosed by a respiratory physician according to the NIH guidelines18 were enrolled in the study. At the baseline visit all subjects underwent the following tests in the order shown: (1) atopic status was determined by skin prick testing with mean weal diameters ⩾4 mm regarded as positive; (2) Juniper asthma control questionnaire; (3) the fraction of nitric oxide in exhaled breath (FeNO) was used as a marker of airway inflammation; (4) MBNW was performed to measure ventilation heterogeneity; and (5) methacholine challenge was undertaken to determine AHR. A subgroup of patients with at least mild persistent asthma, as determined by GINA guidelines,19 were given ICS for 3 months with either chlorofluorocarbon beclomethasone dipropionate (CFC‐BDP) 750 μg twice daily via Autohaler or hydrofluoroalkane beclomethasone dipropionate (HFA‐BDP) 400 μg twice daily via Autohaler (clinically equivalent doses). Since our aim was to investigate overall treatment effects, all treatment data were pooled for analyses.

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and the study was approved by the human ethics review committee of the South‐Western Area Health Service. This study is registered on the Australian Clinical Trials Registry (#ACTRN012605000317695).

Subjects

Subjects with asthma were recruited by advertising throughout the University of Sydney. Inclusion criteria for all subjects with asthma were: (1) no smoking within the last 6 months and <10 pack‐years smoking history; (2) no current lung disease other than asthma; (3) no oral prednisone use in the last 4 weeks; and (4) no respiratory tract infection in the last 4 weeks. Additional inclusion criteria for entry into the 3 month treatment period were: (1) asthma symptoms on at least three occasions a week over the previous month; (2) AHR defined as a provoking dose of methacholine causing a 20% fall in FEV1 of ⩽6.1 μmol; and (3) taking no more than 800 μg/day CFC‐BDP equivalent of ICS.

Two cohorts of healthy non‐asthmatic subjects were recruited from our research staff and the University of Sydney. The first cohort was recruited for the sensitivity and specificity analysis of a parameter from the MBNW test in detecting AHR, and the second cohort was recruited for testing the repeatability of the MBNW indices. Healthy non‐asthmatic subjects were eligible to participate if they had (1) no history of or medication use relating to chronic respiratory disease; (2) no smoking within the last 6 months and <10 pack‐years smoking history; and (3) no respiratory tract infection in the last 4 weeks.

Symptoms

All the subjects with asthma completed the Juniper asthma control questionnaire20 at the baseline visit and after 3 months of treatment (in the treatment subgroup) to assess asthma symptoms within the previous week.

Exhaled nitric oxide

FeNO was measured using an offline technique21 according to American Thoracic Society guidelines. The subject exhaled over 5–15 s into a nitric oxide impermeable polyethylene bag (Scholle Industries Pty Ltd, Elizabeth West, Australia) at a constant flow rate of 0.2 l/s, monitored by rotameter (Dwyer Flowmeter Model VFASS‐25, AMBIT Instruments Pty Ltd, Parramatta, Australia). The exhaled gas was analysed using a chemiluminescence analyser (Thermo Environmental Instruments Model 42C, Franklin, Massachusetts, USA). The upper limit of normal for FeNO has been established as 13 ppb.22

Multiple breath nitrogen washout (MBNW)

The MBNW was performed using a closed circuit bag‐in‐box breathing system to deliver 100% oxygen during inspiration with separate capture of exhaled breath. The nitrogen concentration was measured at the mouth with a Model 721 KaeTech Nitrogen Analyser (KaeTech Instruments Inc, Green Bay, Wisconsin, USA), while flow and volume were recorded from the box by a pneumotachograph. Subjects breathed 100% oxygen at a tidal volume of 1–1.3 litres until the mean expired nitrogen concentration fell to <2%. Three tests were performed with successive tests starting after alveolar nitrogen had returned to baseline. Ventilation heterogeneity indices in the conductive (Scond) and acinar (Sacin) lung zones were derived as previously described17 (see calculations in online supplement available at http://thorax.bmj.com/supplemental). The upper limit of normal for Scond was 0.037/l and for Sacin was 0.130/l, derived from the mean + 1.96 × SD of the value obtained previously in normal subjects.23 The lung clearance index (LCI) was calculated by dividing the cumulative expired volume (CEV) during the washout by the patient's functional residual capacity (FRC) determined from the washout. Details of a repeatability study for Scond, Sacin and LCI obtained from an independent group of patients with asthma and healthy non‐asthmatic patients are given in the online supplement available at http://thorax.bmj.com/supplemental.

Spirometry and bronchial challenge

Spirometry was performed using a Sensormedics Vmax spirometer (Sensormedics Corporation, Yorba Linda, California, USA) and methacholine challenge tests were performed using the rapid method24 via hand‐held De Vilbiss No 45 nebulisers in which doubling doses ranging from 0.05 µmol to 6.1 μmol were administered until the final dose was reached or the forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) fell by ⩾20%. Short acting β‐agonists were withheld for 6 h and long‐acting β‐agonists for 24 h before testing. Response to challenge was measured by the dose response ratio (DRR), which is a continuous variable based on the two‐point slope.25 The DRR is calculated from the final step in the challenge test as % fall in FEV1/methacholine dose (µmol), and a constant of 3 is added to allow for log transformation of zero or negative values. Greater values of DRR indicate greater AHR, and a DRR value of >6.28% fall in FEV1/µmol methacholine + 3 indicates the presence of AHR. This allows inclusion of data from subjects who had a fall in FEV1 of <20% either at baseline or following treatment.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the Analyse‐it for Microsoft Excel software (Analyse‐It Software Ltd, Leeds, UK). DRR and FeNO were log‐normally distributed and were log10 transformed for all analyses. Change in DRR after treatment was expressed as change in doubling dose of methacholine (change in log DRR/0.3). The relationship between AHR (expressed as DRR) and potential predictive factors was examined using univariate analysis (with Pearson's correlation coefficient) and multiple linear regression analyses. The sensitivity and specificity of Scond in predicting AHR was assessed by receiver operator characteristics (ROC) analysis. The paired Student's t test was used for parametric data and the Wilcoxon signed rank test for non‐parametric data to compare outcomes after treatment. Data are presented as means with 95% confidence intervals (CI) unless otherwise specified.

Results

Subjects

Forty subjects with asthma participated in the baseline study; 28 had suboptimally controlled asthma and were eligible for the 3 month treatment study and 24 of these agreed to participate. Four subjects from the treatment subgroup withdrew from the study during treatment and the results of two subjects were excluded from the analysis owing to an upper respiratory tract infection at their post‐treatment visit. Eighteen subjects were therefore included in the treatment subgroup analysis.

Baseline results of entire asthma group

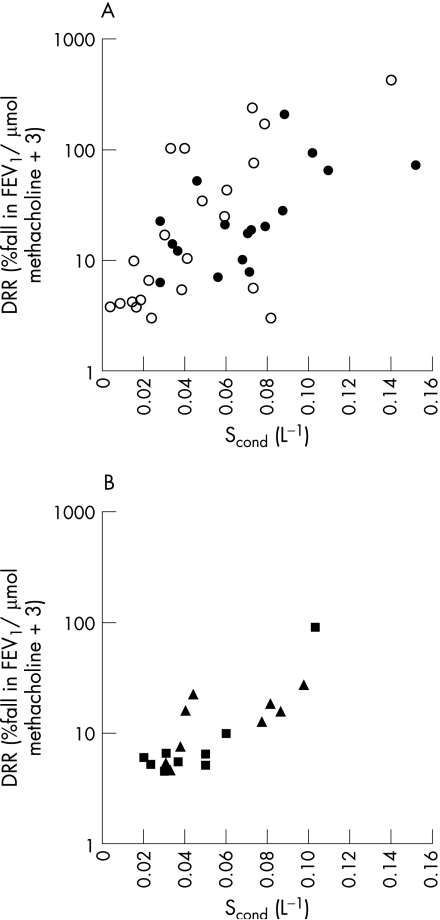

The characteristics of all 40 patients with asthma at baseline are shown in table 1. AHR was present in 31 of the 40 subjects, and log DRR correlated positively with airway inflammation (log FeNO), Scond (fig 1A) and LCI and negatively with % predicted FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio (table 2). Log DRR was not correlated with Sacin (p = 0.67). Log FeNO was not correlated with Scond (r = 0.29, p = 0.07), Sacin (r = 0.20, p = 0.22) or LCI (r = 0.14, p = 0.40) at baseline.

Table 1 Characteristics of study subjects.

| Entire asthma group (n = 40) | ICS treatment asthma subgroup (n = 18) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | After treatment | Absolute difference† (95% CI) | p Value† | ||

| M/F | 20/20 | 9/9 | – | – | – |

| Mean (range) age (years) | 32.1 (18–66) | 33.9 (18–63) | – | – | – |

| Atopic (Y/N) | 40/0 | – | – | – | – |

| FeNO (ppb)* | 15.4 (12.2 to 19.4) | 14.1 | 8.0 | 6.5 (1.5 to 11.6) | 0.002 |

| Scond (/l) | 0.055 (0.03) | 0.067 | 0.052 | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.03) | 0.009 |

| Sacin (/l) | 0.146 (0.02) | 0.159 | 0.142 | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.03) | 0.035 |

| LCI (CEV/FRC) | 8.16 (1.1) | 8.54 | 7.78 | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.1) | 0.001 |

| DRR (% fall FEV1/μmol methacholine+3)* | 18.9 (12.4 to 28.8) | 22.0 | 10.1 | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.6)‡ | <0.001 |

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 82.4 (11.7) | 80.1 | 85.9 | 5.8 (3.2 to 8.4) | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | 0.76 (0.08) | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04) | 0.04 |

| β agonist use (times/day) | 1.4 (2.4) | 1.95 | 0.54 | 0.8 (−0.0 to 1.6) | 0.07 |

| BDP equivalent dose (μg/day) | 320 (449.6) | 270 | 1500 | – | – |

| Juniper symptom score | 1.28 (0.84) | 1.48 | 0.81 | 0.7 (0.4 to 0.9) | <0.001 |

Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise stated.

*Geometric mean and 95% CI

†Comparison between values before and after treatment.

‡Doubling dose difference in DRR.

BDP, beclomethasone dipropionate; CEV, cumulative expired volume; DRR, dose response ratio; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FeNO, fraction of nitric oxide in exhaled breath; FRC, functional residual capacity; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LCI, lung clearance index; MBNW, multiple breath nitrogen washout; Scond, ventilation heterogeneity in the conducting airways; Sacin, ventilation heterogeneity in acinar lung zone; ppb, parts per billion.

Figure 1 (A) Conductive airway ventilation heterogeneity (Scond) correlates with airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) (log DRR) at baseline (r = 0.63, p<0.001). Closed circles represent those who participated in the inhaled corticosteroid treatment study and open circles represent those who did not. (B) Scond continues to correlate with AHR following treatment (r = 0.82, p<0.001). Triangles represent subjects treated with chlorofluorocarbon beclomethasone dipropionate (CFC‐BDP) and squares represent subjects treated with hydrofluoroalkane beclomethasone dipropionate (HFA‐BDP).

Table 2 Pearson correlation coefficients (r) of baseline variables with airway hyperresponsiveness (dose response ratio, DRR) for the asthmatic group as a whole and for the treatment subgroup before and after treatment.

| Baseline asthma group (n = 40) | Baseline treatment subgroup (n = 18) | Post‐treatment treatment subgroup (n = 18) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p Value | r | p Value | r | p Value | |

| Airway inflammation (FENO) | 0.62 | <0.001 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.61 | 0.008 |

| Ventilation heterogeneity (Scond) | 0.63 | <0.001 | 0.64 | 0.004 | 0.82 | <0.001 |

| Ventilation heterogeneity (Sacin) | 0.07 | 0.67 | 0.04 | 0.86 | −0.02 | 0.93 |

| Ventilation heterogeneity (LCI) | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.21 | 0.47 | 0.05 |

| FEV1 % predicted | −0.44 | 0.005 | −0.40 | 0.10 | −0.37 | 0.13 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | −0.47 | 0.002 | −0.34 | 0.17 | −0.21 | 0.41 |

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FeNO, fraction of nitric oxide in exhaled breath; FVC, forced vital capacity; LCI, lung clearance index; Scond, ventilation heterogeneity in conducting airways; Sacin, ventilation heterogeneity in acinar lung zone

In a multiple linear regression model which included the significant factors in table 2, log DRR was significantly predicted by both log FeNO (partial r2 = 0.20, p<0.001, β coefficient 0.9, 95% CI 0.5 to 1.3) and Scond (partial r2 = 0.39, p<0.001, β coefficient 8.5, 95% CI 4.8 to 12.2). LCI, % predicted FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio were not significant predictors of log DRR (p = 0.90, p = 0.25 and p = 0.97, respectively) when included separately or together in this model.

Inhaled corticosteroid treatment subgroup

The characteristics of the 18 subjects with asthma in the treatment subgroup are shown in table 1. Following treatment there were significant improvements in DRR, FeNO, Scond, Sacin, LCI, FEV1 (% predicted) and the Juniper symptom score (table 1), but AHR was still present in 10 of the 18 subjects. The univariate correlations at baseline in this subgroup were similar to those in the group as a whole (table 2, fig 1B). However, LCI, % predicted FEV1 and the FEV1/FVC ratio were not correlated with log DRR either before or after treatment in the treatment subgroup (table 2).

In a multiple linear regression model, log DRR in the treatment subgroup was predicted solely by Scond both before (r2 = 0.38, p = 0.004, β coefficient 8.3, 95% CI 3.1 to 13.6) and after treatment (r2 = 0.64, p<0.001, β coefficient 10.9, 95% CI 6.8 to 15). Log FeNO, LCI, % predicted FEV1 and the FEV1/FVC ratio were not significant predictors of log DRR either before (p = 0.18, p = 0.90, p = 0.24, p = 0.99, respectively) or after treatment (p = 0.38, p = 0.30, p = 0.25, p = 0.42, respectively) in the multivariate regression model.

The magnitude of improvement in AHR correlated with both the reductions in FeNO and Scond (F = 3.94, p = 0.04 for the multivariate model), but there was no correlation between the reductions in Scond and FeNO0.2 following treatment (r = 0.07, p = 0.77). There were no differences in the magnitude of improvements in FeNO (p = 0.26), Scond (p = 0.81) or DRR (p = 0.90) between subjects treated with HFA‐BDP or CFC‐BDP (corresponding post‐treatment data are represented by squares and triangles in fig 1B).

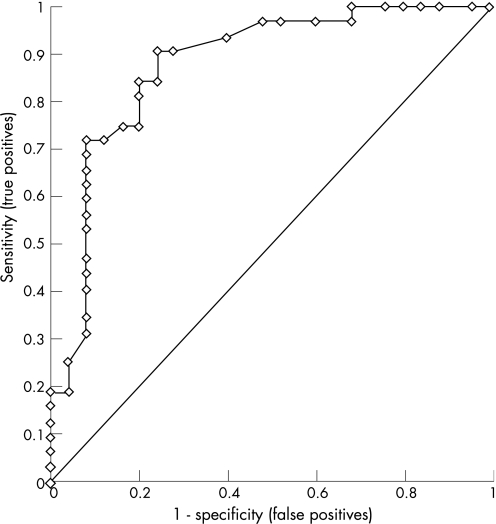

Scond as a predictor of AHR

Based on the correlation between AHR and Scond, we combined the patients with asthma from this study (n = 40) with a cohort of 17 healthy non‐asthmatic subjects (their characteristics are summarised in table E1 in the supplementary data available online at http://thorax.bmj.com/supplemental) to test whether Scond was a significant predictor of the presence of AHR using ROC analysis (fig 2). The area under the ROC curve was 0.88 (p<0.0001), and the cut‐off value of Scond = 0.037/l corresponding to the upper limit of normal range26 gave a good combination of sensitivity and specificity (71.9% and 90.0%, respectively) for detecting the presence of AHR. Using the same cut‐off value (0.037/l), Scond remained a significant predictor of the presence of AHR after treatment in our 18 subjects from the subgroup (area under the ROC curve = 0.96, p<0.0001) with a high sensitivity and specificity (90.0% and 87.5%, respectively, see fig E2 in the supplementary data available online at http://thorax.bmj.com/supplemental).

Figure 2 Sensitivity and specificity of ventilation heterogeneity in conducting airways (Scond) in predicting the presence or absence of airway hyperresponsiveness in a combination of 40 patients with asthma and 17 healthy non‐asthmatic subjects at baseline.

Repeatability of Scond, Sacin and LCI

The characteristics of the cohort of 10 subjects with asthma and 11 healthy non‐asthmatic subjects who participated in the repeatability study of the MBNW indices are summarised in table E2 in the supplementary data (available online at http://thorax.bmj.com/supplemental). In subjects with asthma, Scond, Sacin and LCI had a good repeatability with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.84 (95% limits of agreement ±0.026) for Scond, 0.95 (95% limits of agreement ±0.027) for Sacin, and 0.91 (95% limits of agreement ±0.735) for LCI. The repeatability results for the healthy non‐asthmatic subjects are shown in table E3 in the supplementary data (available online at http://thorax.bmj.com/supplemental).

Discussion

In this study we have shown that baseline ventilation heterogeneity correlates strongly with the severity of AHR in subjects with asthma with a range of disease severity. In particular, Scond predicted AHR to methacholine independently of airway inflammation and airway calibre. Importantly, the strong correlation between Scond and AHR persisted after airway inflammation was reduced with ICS treatment. Following treatment, Scond was, in fact, the sole independent predictor of AHR. The improvement in Scond with ICS treatment suggests that it is determined, at least in part, by steroid‐responsive inflammatory processes. However, the residual ventilation heterogeneity which persisted after ICS treatment suggests that non‐steroid responsive or non‐inflammatory factors also make an important contribution to ventilation heterogeneity. The conductive airways, where the residual ventilation heterogeneity responsible for AHR after anti‐inflammatory treatment originates, clearly constitute an important therapeutic target. These findings are novel and have clinical implications in patients with asthma.

Ventilation heterogeneity in the lungs is a well recognised feature of asthma,12 but its clinical significance—apart from the deleterious effects on gas exchange27—has been uncertain. In our study, the main contribution to ventilation heterogeneity that was associated with AHR originated in the conductive airways. Gustafsson et al5 reported a correlation between airway responsiveness to cold air challenge and ventilation heterogeneity measured by single breath washout using helium and SF6, which indicated an involvement of peripheral airways but did not assess the contribution of airway inflammation. It is impossible independently to determine ventilation heterogeneity of conductive airways from the single breath washout, making comparison with the present study difficult. However, despite methodological differences in the determination of ventilation heterogeneity and AHR, the observed correlations between ventilation heterogeneity and AHR in both studies suggest a robust association. In the present study, AHR was not correlated with baseline acinar (Sacin) ventilation heterogeneity, signalling that the important lung region with regard to the relationship between ventilation heterogeneity and AHR is specifically in the conducting airways. The weak correlation between the LCI and AHR indicates that this measure of specific ventilation distribution between relatively large lung units, which also partly contributes to Scond, is neither sensitive nor specific as a measure of the conductive airway heterogeneity underlying AHR.

The significant reduction in ventilation heterogeneity in our subjects following anti‐inflammatory ICS treatment suggests that ventilation heterogeneity is partly due to steroid‐responsive airway inflammation. After treatment, residual ventilation heterogeneity persisted in the presence of normalised mean exhaled nitric oxide levels, suggesting that other inflammatory processes not related to exhaled nitric oxide, or non‐inflammatory processes, could also contribute to ventilation heterogeneity. Exhaled nitric oxide correlates with sputum eosinophils,28 but it does not reflect the full spectrum of inflammatory and non‐inflammatory processes associated with asthma. This may explain the lack of association between improvement in exhaled nitric oxide and ventilation heterogeneity during treatment. Ventilation heterogeneity could also continue to improve with further ICS treatment, as has been shown to occur with AHR which can continue to improve up to and after 12 months of treatment.29 It would be valuable in future studies also to assess any additional benefits of systemic treatments on ventilation heterogeneity.

The residual ventilation heterogeneity present at the end of treatment may also be caused by non‐inflammatory structural changes such as airway remodelling or increased smooth muscle tone. Structural changes induced by airway remodelling are likely to be heterogeneously distributed among parallel pathways of the bronchial tree. These structural changes manifest as altered composition and organisation of the soft tissues of the airway walls and are believed to be a result of chronic or repeated episodes of acute inflammation.30 The changes include thickening of the airway wall, smooth muscle hyperplasia and hypertrophy, subepithelial fibrosis and mucous metaplasia. It is possible that many, if not all, of these abnormalities may contribute to ventilation heterogeneity by exaggerating the inherent heterogeneity of the airway tree and by being unevenly distributed themselves.

Increased baseline ventilation heterogeneity may cause a heterogeneous distribution of methacholine aerosol resulting in high concentrations of methacholine delivered to a small surface area of the airways. In a previous study, central‐to‐peripheral airway differences in the pattern of methacholine deposition in subjects with asthma did not alter AHR.31 However, a recent imaging study in sheep32 showed that the regions of lung with the highest baseline ventilation were the same regions which became constricted after methacholine, suggesting a link between parallel ventilation heterogeneity and methacholine deposition. This could partly explain the association between Scond (representative of parallel ventilation heterogeneity) and AHR. The exact mechanism by which ventilation heterogeneity may cause AHR remains unclear. However, a recent modelling study12 showed that only minor alterations in structure, function or smooth muscle activity in a virtually uniform airway tree are required to trigger extreme ventilation heterogeneity during uniformly applied bronchoconstriction.

One of the strengths of our study was the wide range of asthma severity in the group of subjects tested at baseline. Indices of ventilation heterogeneity from the MBNW were robust, repeatable and comparable with values obtained in other subjects with asthma.17,33 The strong predictive capacity of Scond for the presence of AHR, as inferred from our ROC analysis (fig 2), is reinforced because the upper limit of the normal range for Scond (0.037/l) corresponded to a high combination of sensitivity and specificity for detecting the presence of AHR in the present study. This raises the possibility that Scond could at least partly be used to predict AHR as part of the clinical management of asthma. MBNW tests can be performed in patients whose lung function is too low to permit bronchial challenge and has been successfully administered in non‐sedated children with a number of airway diseases.34

In summary, we have shown for the first time that ventilation heterogeneity in the conducting airways is a significant predictor of AHR in subjects with asthma, independent of airway inflammation as measured by exhaled nitric oxide, both before and after ICS treatment. Inflammatory and non‐inflammatory processes which could alter the structural features within the airway tree may contribute to ventilation heterogeneity. Based on the strength of the correlations in this study and on the results of computational modelling,12,13,14 it is possible that ventilation heterogeneity is an important contributor to AHR in asthma. The index Scond derived from the MBNW is a measure of conducting airway function that is likely to be useful in the clinical management of asthma and for the assessment of new treatment strategies and drugs in this disease. These findings suggest that greater understanding of the determinants of ventilation heterogeneity may lead to more efficacious asthma treatment and can provide an additional tool for monitoring treatment, resulting in improved long‐term outcomes for patients with asthma.

Additional data are available in the online supplement at http://thorax.bmj.com/supplemental.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the volunteers who participated in the study; Nathan Brown, Chantale Diba, Phillip Munoz, Dr Ricardo Starling‐Schwanz, Dr Stephen Vincent and Dr Ciça Santos who assisted with patient visits; Gunnar Unger and Tom Li who gave engineering support for the multiple breath nitrogen washout; and Wei Xuan for his advice on statistical analysis.

Abbreviations

AHR - airway hyperresponsiveness

CEV - cumulative expired volume

CFC‐BDP - chlorofluorocarbon beclomethasone dipropionate

DRR - dose response ratio

FEV1 - forced expiratory volume in 1 s

FRC - functional residual capacity

FeNO - fraction of nitric oxide in exhaled breath

FVC - forced vital capacity

HFA‐BDP - hydrofluoroalkane beclomethasone dipropionate

ICS - inhaled corticosteroid

LCI - lung clearance index

MBNW - multiple breath nitrogen washout

ROC - receiver operator characteristics

Sacin - ventilation heterogeneity in acinar lung zone

Scond - ventilation heterogeneity in conducting airways

Footnotes

This project was funded by the Cooperative Research Centre for Asthma.

Competing interests: The authors have the following potential conflicts of interest to declare: Cheryl M Salome states that her research group has received support from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca but these do not pose any conflict of interest for this paper. Norbert Berend serves on advisory boards for GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim and AstraZeneca, and The Woolcock Institute of Medical Research of which he is the Director receives research grants from GlaxoSmithKline. Gregory King has received travel sponsorship from GlaxoSmithKline to attend the ATS ASM 2003 (approximately $A9000) and a GlaxoSmithKline meeting in 2003 (approximately $A10 000), travel sponsorship from AstraZeneca to attend ATS ASM 2004 (approximately $A10 000) and two AstraZeneca scientific meetings (approximate combined value $A20 000), an honorarium paid to his research institute from GlaxoSmithKline to speak at a sponsored conference in South East Asia ($A3000) in 2005, a travel grant from AstraZeneca to attend the ATS 2005 ($A6000) and a travel grant from GlaxoSmithKline to attend the ATS 2006 ($A5000). A proportion of Dr King's research work is conducted at the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research which receives unrestricted grants from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim and Vita Medical for such work. The Woolcock Institute of Medical Research also has a consultancy agreement with Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline for which Dr King provides consultancy services related to asthma and COPD. His research group receives a proportion of the grants and monies that arise from those companies as part of specific and general allocations of those funds for research purposes across all research groups of the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research. Dr King does not own any stocks, equity or patents that pose a conflict of interest.

Additional data are available in the online supplement at http://thorax.bmj.com/supplemental.

References

- 1.Macklem P. Bronchial hyporesponsiveness. Chest 198791S189–91S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leuppi J D, Salome C M, Jenkins C R.et al Predictive markers of asthma exacerbation during stepwise dose reduction of inhaled corticosteroids (see comment). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001163406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xuan W, Peak J, Toelle B.et al Lung function growth and its relation to airway hyperresponsiveness and recent wheeze. Results from a longitudinal population study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20001611820–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid D W, Johns D P, Feltis B.et al Exhaled nitric oxide continues to reflect airway hyperresponsiveness and disease activity in inhaled corticosteroid‐treated adult asthmatic patients. Respirology 20038479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gustafsson P M, Ljungberg H K, Kjellman B. Peripheral airway involvement in asthma assessed by single‐breath SF6 and He washout. Eur Respir J 2003211033–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Report National Heart, Lung and Blood Insitute/World Health Organization Pocket guide for asthma management and prevention – Global Initiative for Asthma. 2005. pp. 1–27.

- 7.Obase Y, Shimoda T, Mitsuta K.et al Correlation between airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation in a young adult population: eosinophil, ECP, and cytokine levels in induced sputum. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 200186304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crimi E, Spanevello A, Neri M.et al Dissociation between airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in allergic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 19981574–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moller G M, Overbeek S E, van Helden‐Meeuwsen C G.et al Eosinophils in the bronchial mucosa in relation to methacholine dose‐response curves in atopic asthma. J Appl Physiol 1999861352–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson J L, Scott R J, Boyle M J.et al Differential proteolytic enzyme activity in eosinophilic and neutrophilic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005172559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lanz M J, Leung D Y, McCormick D R.et al Comparison of exhaled nitric oxide, serum eosinophilic cationic protein, and soluble interleukin‐2 receptor in exacerbations of pediatric asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol 199724305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venegas J G, Winkler T, Musch G.et al Self‐organized patchiness in asthma as a prelude to catastrophic shifts. Nature 2005434777–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorpe C W, Bates J H T. Effect of stochastic heterogeneity on lung impedence during acute bronchoconstriction: a model analysis. J Appl Physiol 1997821616–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lutchen K R, Gillis H. Relationship between heterogeneous changes in airway morphometry and lung resistance and elastance. J Appl Physiol 1997831192–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verbanck S, Schuermans D, Meysman M.et al Noninvasive assessment of airway alterations in smokers. The small airways revisited. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004170414–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crawford A B, Makowska M, Paiva M.et al Convection‐ and diffusion‐dependent ventilation maldistribution in normal subjects. J Appl Physiol 198559838–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verbanck S, Schuermans D, Noppen M.et al Evidence of acinar airway involvement in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 19991591545–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Washington, DC: NIH, 1997 [PubMed]

- 19.Global Initiative for Asthma Pocket guide for asthma management and prevention. Medical Communications Resources, 2004

- 20.Juniper E F, O'Byrne P M, Guyatt G H.et al Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur Respir J 199914902–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salome C M, Roberts A M, Brown N J.et al Exhaled nitric oxide measurements in a population sample of young adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999159911–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deykin A, Massaro A F, Drazen J M.et al Exhaled nitric oxide as a diagnostic test for asthma: online versus offline techniques and effect of flow rate (see comment). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20021651597–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King G G, Downie S R, Verbanck S.et al Effects of methacholine on small airway function measured by forced oscillation technique and multiple breath nitrogen washout in normal subjects. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2005148165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan K, Salome C M, Woolcock A J. Rapid method for the measurement of bronchial responsiveness. Thorax 198338760–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Connor G, Sparrow D, Taylor D.et al Analysis of dose response curves to methacholine. An approach suitable for population studies. Am Rev Respir Dis 19871361412–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King G G, Carroll J D, Muller N L.et al Heterogeneity of narrowing in normal and asthmatic airways measured by HRCT. Eur Respir J 200424211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez‐Roisin R. Gas exchange abnormalities in asthma. Lung 1990168(Suppl)599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beier J, Beeh K M, Kornmann O.et al Sputum induction leads to a decrease of exhaled nitric oxide unrelated to airflow. Eur Respir J 200322354–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ward C, Pais M, Bish R.et al Airway inflammation, basement membrane thickening and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in asthma (see comment). Thorax 200257309–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vignola A M, Mirabella F, Costanzo G.et al Airway remodeling in asthma. Chest 2003123(3 Suppl)417–22S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Riordan T G, Walser T G L, Smaldone G C. Changing patterns of aerosol deposition during methacholine bronchoprovocation. Chest 19931031385–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venegas J G, Schroeder T, Harris S.et al The distribution of ventilation during bronchoconstriction is patchy and bimodal: a PET imaging study. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 200514857–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verbanck S, Schuermans D, Paiva M.et al Nonreversible conductive airway ventilation heterogeneity in mild asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003941380–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aurora P, Kozlowska W, Stocks J. Gas mixing efficiency from birth to adulthood measured by multiple‐breath washout. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2005148125–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.