Abstract

Validated outcome measures are essential in monitoring disease severity. Specifically in dermatology, which relies heavily on the clinical evaluation of the patient and not on laboratory values and radiographic tests, outcome measures help standardize patient care. Validated cutaneous scoring systems, much like standardized laboratory values, facilitate disease management and follow therapeutic response. Several cutaneous autoimmune dermatoses, specifically cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE), dermatomyositis (DM), and pemphigus vulgaris (PV), lack such outcome measures. As a result, evaluation of disease severity and patients’ response to therapy over time is less reliable. Ultimately, patient care is compromised. These diseases, which are often chronic and relapsing and remitting, are also often refractory to treatment. Without outcome measures, new therapies cannot be systematically assessed in these diseases. Clinical trials that are completed without standardized outcome measures produce less reliable results. Therefore, the development of validated outcome measures in these autoimmune dermatoses is critical. However, the process of developing these tools is as important, if not more so, than their availability. This review examines the steps that should be considered when developing outcome measures, while further examining their importance in clinical practice and trials. Finally, this review more closely looks at CLE, DM, and PV and addresses the recent and ongoing progress that has been made in the development of their outcome measures.

Introduction

Validated and responsive outcome measures in dermatology are essential to optimal patient care. Objectively monitoring disease severity over time is required to ensure treatment efficacy. Within the field of dermatology, such measures exist for the more common diseases, such as the psoriasis activity and severity index (PASI) [11, 37] and the severity scoring of atopic dermatitis (SCORAD) [18]. In 2000, a review identified 13 distinct outcome measures for atopic dermatitis, including the six-area, six-sign atopic dermatitis severity score (SASSAD) and the Eczema area and severity index (EASI) [7]. Additional scores include the Vitiligo disease activity score (VIDA) [21], as well as severity scoring systems for acne [9] and rosacea [23]. However, the autoimmune dermatoses, such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE), dermatomyositis (DM), and pemphigus vulgaris (PV), which are far less common, lack such measures. In general, these diseases wax and wane and can be refractory to treatment. Both active disease and damage from burnt out disease can cause significant patient morbidity. Monitoring response to therapy becomes subjective and unreliable in the absence of such validated outcome measures. Drug trials require systematic monitoring of changes in disease severity. It is impossible to perform reliable trials and compare outcomes between trials without validated outcome measures. Scoring systems for these and other autoimmune dermatoses must be developed in order to monitor drug efficacy and establish the need for new therapies.

Usefulness of validated scoring systems

The ability to objectively measure disease severity in any field is imperative to the practice of evidence based medicine. Validated scoring systems may be generated and used for a group of diseases, or may be developed for individual diseases. In most instances in dermatology, a disease specific outcome measure is more beneficial since inherent subtleties within diseases are important to disease severity. The ability to monitor disease severity over time and response to treatment is essential to effective patient care.

Scoring systems, in general, are useful for cost containment with the elimination of ineffective interventions and evaluation of quality of care differences across different providers. Furthermore, the results of any clinical study are only as good as their endpoints [36]. Uniformly used scoring systems make it possible to compare results of clinical trials. Without the availability of globally agreed upon outcomes measures, there is less systematic analysis of drug efficacy making it difficult to justify the use of such drug in the clinical setting. This holds true for not only new therapies, but also for new indications of currently available therapies.

Development of scoring systems

The FDA has set guidelines for measuring clinical response: measure activity, disease-induced damage, response as determined by the patient, and health-related quality-of-life [10]. The development of usable outcome measures requires the collaboration of researchers, clinicians and patients to determine what elements of any disease should be measured and how. Parameters that constitute disease activity must be clearly defined. These parameters must also be sensitive to detect improvement in disease severity over time. As a whole, the tool itself must be easy to use. In many cases it is not necessary to capture all elements of disease severity, as certain parameters may not be sensitive or specific over time. Feasibility of use in a busy clinical setting must be considered when developing these measures.

Once tools are developed they need to be validated. If the tools are going to be used by multiple subspecialists (i.e. dermatologists and rheumatologists), then they should be validated by both groups. Singer et al. [29] define several desirable features of scoring systems. Ideally, clinical outcome measures should be credible (face validity), comprehensive (content validity), sensitive (discriminant validity), accurate (criterion validity), feasible, and should make biological sense (construct validity). In this way, a scoring system would take into consideration not only what the patients deem most important, but also what the clinicians deem to be most clinically relevant.

A valid outcome measure is one that measures what it is supposed to be measuring. However, validity is not by itself enough. Scoring systems must also be reliable. Reliability is the consistency of a set of measurements, or the repeatability of measurements. Williams et al. [36] points out that there should be reliability within an observer and between observers. There should also be internal consistency (of items within a scale), sensitivity to change, and acceptability (in terms of time, resources, and costs needed to complete the measure). Finally, validated and reliable tools should be used in conjunction with and compared to other less specific measures of disease severity, such as analog physician and patient global skin health scores, as well as pain, itch and fatigue scales [13].

The development of scoring systems should occur over time with many collaborators willing to continually revise and refine the tool until it is comprehensive without being burdensome. Finlay [12] recommends that scoring systems have the following qualities: it must be simple enough to use in busy clinical setting, include both objective physician scores and subjective patient scores but also clearly separate these scores. Parameters used should be unambiguous in their meaning and amenable to change as needed. These parameters should also be able to detect change in disease severity over time. Finlay also specifically points out that site involvement, and not simply estimated percent surface area, should be clearly documented.

What is known from dermatologic diseases with widely used scoring systems

There are currently a wide array of outcome measures available for various dermatoses, both disease specific and not. For example, the dermatology index of disease severity (DIDS) is used for staging the severity of inflammatory skin disease [15]. It measures the therapeutic effectiveness and magnitude of clinical improvement in several types of dermatitis, eczema and psoriasis by assessing body surface area (BSA) and degree of functional limitation. The SCORAD, used in atopic dermatitis, is another example of a dermatologic outcome measure that uses BSA to estimate extent of disease involvement. BSA is often used in outcome measures to estimate extent of disease involvement.

However, several investigators [7, 8, 26, 33] have found that measuring BSA does not work, as results are often difficult to reproduce, both within and across clinicians. Furthermore, estimating BSA may underestimate disease severity in diseases that are often confined to small areas of the body. For example, widespread SCLE, which often resolves without permanent damage, may be more benign than severe localized discoid LE that is confined to the scalp and face and may lead to severe disfigurement [19]. Additionally, improvement in disease that involves only a small area may be difficult to measure, limiting its use in clinical trials.

Another method commonly used to assess extent of disease involvement is lesion counting. However, Lucky et al. [2] found that lesion counting was no more reliable than estimating BSA when studying acne. Furthermore, acne lesions tend to be fairly distinct. Lesion counting would be almost impossible in diseases such as SCLE where lesions tend to coalesce and are often not distinct. Again, with this method, monitoring disease improvement would be very difficult, specifically because as larger lesions heal they may break up into smaller lesions and paradoxically increase the total lesion count [19].

Scoring systems in autoimmune dermatoses

It is conceptually easy to understand why scoring systems, in some cases more than one, exist for relatively common skin diseases. The development of these tools requires an accessible patient population on which the tool can be tested, revised, and perfected. Without this patient population, the development of scoring systems becomes much more difficult.

There is a growing need for validated outcome measures in autoimmune dermatoses as more clinical trials are being developed and more therapies are becoming available to be tested in these diseases. Currently, most scoring systems being used are disease specific, but are developed for specific trials by individual investigators. There needs to be a collaboration of investigators across dermatology and in some cases, specifically with autoimmune dermatoses, across subspecialties to create tools that will be used more broadly. In this way, it becomes possible to compare results across clinical trials and implement study findings into clinical practice.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE), DM, and PV are three examples of autoimmune dermatoses that either lack or until recently lacked validated outcome measures. They are also three examples of difficult to treat diseases that would easily benefit from systematic evaluation of newly available therapies and/or therapies that are currently being used in other diseases. A closer evaluation of each of these dermatoses will help illustrate the need for validated scoring systems.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis

Both lupus erythematosus (LE) and DM are complex multi-system autoimmune disorders, characterized by fluctuations in disease severity. Both include a subset of patients who only have cutaneous involvement. In lupus, while precise data is not available, it is believed that pure CLE may be two to three times more prevalent than SLE [32]. In DM, there is a sub-set of patients with purely cutaneous disease, known as amyopathic DM, which reportedly occurs in about 20–40% of DM patients seen by dermatologists [3, 25, 30]. Scoring systems are not only needed to evaluate the severity of skin involvement but may also provide an alternate way to monitor systemic disease.

In addition, the FDA recently revised their guidelines for the development of therapeutics in SLE, permitting the approval of drugs that show efficacy in one organ system [6]. Therefore, improvement in the skin alone became sufficient to get a drug approved through the FDA. This change facilitates the development of drug trials and expands the possible drugs that can be evaluated in cutaneous LE. However, this change also necessitates the development of a skin specific outcome measure in order to objectively evaluate drug efficacy.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Most epidemiological studies have found that skin involvement is the second most common manifestation of SLE and is the second most frequent presenting manifestation [31]. Yet the cutaneous manifestations are among the least well-studied aspect of this multi-system autoimmune illness. This is in part due to the fact that until recently there was no tool available to systematically evaluate the severity of skin disease.

A recent retrospective study identified 60 measures of SLE, but found only 3 to be useful for dermatologists [28]. The SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) [16] scores the presence of rash, alopecia, or mucosal ulcers independent of extent and allots a maximum of 6 points to these findings, with a maximum total score of 105. The lupus activity criteria count (LACC) [22, 34] scores skin involvement as one of seven possible organ systems involved and for the purpose of monitoring severity of skin disease would be essentially useless. Finally, the SLICC/ACR damage index for systemic lupus erythematosus [4, 14] gives one point each for scarring alopecia, extensive scarring other than the scalp or pulp space, and skin ulceration (excluding thrombosis) for more than 6 months, accounting for a possible 3 points out of 48. None of these tools for SLE adequately measure skin involvement for the purposes of clinical trials.

The cutaneous lupus area and severity index (CLASI) was developed specifically to measure disease severity in CLE, to facilitate drug trials in CLE. First, a consensus as to what the salient features of CLE are needed, including what parameters should be measured to define activity. Early on in the design process, it was decided that damage as well as activity should be measured because in many cases of CLE, specifically the scarring forms such as discoid LE, damage plays a major role in patient morbidity. This differentiation of activity and damage enable the evaluation of therapies on both elements of the disease process, since it is the goal to minimize both activity and permanent damage. Certain subtypes of CLE may produce permanent damage and disfigurement, making early intervention with effective therapies and prevention of such damage critical to the long-term well-being of patients. Ultimately, a collaborative effort by the international cutaneous lupus community generated and promoted the use of a single, validated outcome measure in CLE [2].

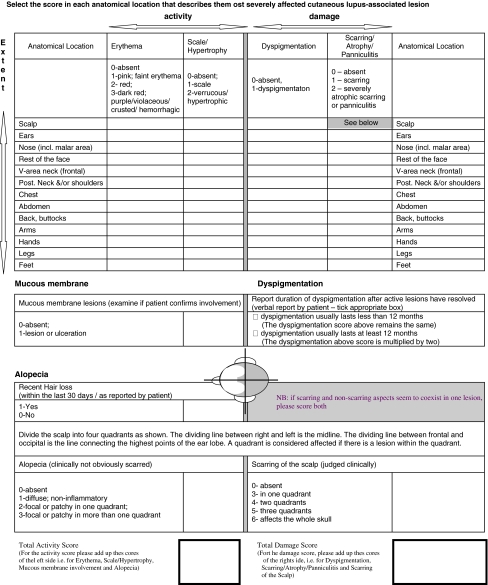

The CLASI, developed by Albrecht and Werth [2], consists of an activity and damage score (Fig. 1). The activity score takes into account erythema (0–3), scale/hypertrophy (0–2), mucous membrane lesions (0–1), recent hair loss (0–1) and non-scarring alopecia (0–3). The damage score represents dyspigmentation (0–1), scarring/atrophy/panniculitis (0–2), and scarring of the scalp (0–6). Patients are asked if their dyspigmentation lasts 12 months or longer, in which case, the dyspigmentation score is doubled. Each of the above parameters is measured in 13 different anatomical locations, included specifically because they are most often involved in CLE. The most severe lesion in each area is measured.

Fig. 1.

Cutaneous LE disease area and severity index (CLASI)

The CLASI has been shown to be a valid and reliable outcome measure for CLE in three different studies. Content validity was established by experts in the field of dermatology. Inter-rater reliability correlation coefficients were 0.86 for the activity score (95%CI = 0.73–0.99) and 0.92 for the damage score (95%CI = 0.85–1.00). Intra-rater reliability correlation coefficients were 0.96 (95%CI = 0.89–1.00) for activity and 0.99 (95%CI = 0.97–1.00) for damage [1]. The second study [5], a prospective clinical trial, showed the CLASI to be clinically responsive to change in disease severity over time. The change in the CLASI activity score was highly correlated with the change in the physician’s global assessment of skin health (r = 0.87, P = 0.005), the change in patient’s global skin health score (r = 0.85, P = 0.004), and the change in the patient rated pain score (r = 0.98, P = 0.004). The third study [17] showed reliability of the CLASI across dermatologists and rheumatologists. Clinicians from both subspecialties were able to use the CLASI to assess disease severity in 14 patients. The dermatologists had an intra-class coefficient of r = 0.92 for activity and of r = 0.81 for damage. The rheumatologists had an intra-class coefficient of r = 0.82 and of 0.86 for damage. Intra-rater reliability, measured with Spearman’s ρ, was 0.94 for activity and 0.97 for damage amongst the dermatologists. Intra-rater reliability for the rheumatologists for activity was 0.91 and for damage was 0.99.

Dermatomyositis

Approximately 60% of patients with adult-onset classical DM have concurrent presentation of both skin and muscle involvement, while about 30% present with skin symptoms weeks to months prior to the onset of muscle involvement. The final 10% have muscle involvement preceding the development of skin disease [31]. While there is no one well-defined pattern of muscle and skin involvement in DM, the two are clearly related. Systematic evaluation of skin involvement is critical to evaluate the efficacy of therapy of DM.

Development of the cutaneous dermatomyositis area and severity index (CDASI), for the purpose of clinical trials and monitoring treatment response, is currently underway. Information generated from other related studies was used to help develop the CDASI. Specifically, Rider et al. [28] developed and validated global assessment tools for juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. They found that treating physicians deem cutaneous findings of these myopathies important indicators of activity, even when associated with more severe gastrointestinal and muscular symptoms. In DM, cutaneous symptoms must be evaluated separately from other systemic symptoms in order to fully appreciate disease severity, especially in the absence of muscle symptoms, as with ADM patients.

In addition, calcinosis was found to have the most impact on damage scores [28]. As in CLE, untreated lesions may cause permanent morbidity and disability, such as poikiloderma and cutaneous calcinosis. Therefore, the CDASI, like the CLASI, measures activity and damage separately. The CDASI has 4 activity (erythema, scale, excoriation, ulceration) and 2 damage (poikiloderma, calcinosis) measures for 18 anatomical locations, with scores ranging from 0 to 148. The CDASI also specifically measures the hands (Gottron’s), the periungual area, and alopecia, with use of different measurements than those used at the other anatomical locations. As with the CLASI, the elements that compose the CDASI activity score are well-established and likely amenable to change with treatment, although a study to examine this has yet to be performed.

A recent study examined the reliability and validity of three tools, the CDASI, the dermatomyositis skin severity index (DSSI), and the cutaneous assessment tool (CAT) [27] in measuring disease severity in patients with DM [16]. Ten dermatologists evaluated 12–16 patients with all 3 tools. Reliability studies demonstrated an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) for test-retest intra-rater reliability of 0.86 for CDASI (95%CI = 0.74–0.98), 0.93 for DSSI (95%CI = 0.87–0.99), and 0.55 for CAT (95%CI = 0.23–0.88). Inter-rater reliability studies showed an ICC of 0.83 (95%CI = 0.72–0.94) for CDASI, 0.44 (95%CI = 0.23–0.65) for DSSI, and 0.61 (95%CI = 0.42–0.80) for CAT. In addition, DSSI scores were skewed to the low end of the scale, suggesting that these scores would be less sensitive to changes in disease severity over time. The CAT has poorer inter- and intra-rater reliability than the CDASI, suggesting that the CDASI may be the most useful measure of cutaneous disease severity in DM.

Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is a rare, potentially life-threatening, autoimmune blistering disorder. The incidence of PV varies from 0.5 to 3.2/100,000 people. Flaccid bullae develop on mucous membranes and skin. Unlike CLE and DM, lesions in PV are often non-scarring. However, 50–70% of patients with PV have mucosal involvement, which may cause dysphagia and other related morbidity. Immunosuppressive therapies used in the treatment of PV are the primary cause of morbidity and mortality in PV patients. Validated outcome measures are needed for the development and evaluation of new, less toxic therapies for PV.

Three randomized controlled multicenter trials have ever been reported in PV. One examined the use of dapsone as a steroid-sparing drug in maintenance phase PV [35], one the role of adjuvant pulse glucocorticoids in PV [20], a third examined the role of two immunosuppressives as steroid-sparing agents in PV [3]. There are currently several ongoing trials in PV, but these trials cannot be compared until an agreed upon outcome tool is developed to accurately measure PV disease activity over time. At this point, outcome measures for PV are being developed on an as needed basis whenever trials are done. This lack of uniformity greatly compromises the generalizability of the study results, making it difficult to compare results across trials.

Several outcomes measures for pemphigus have been developed. Most recently published, the autoimmune bullous skin disorder intensity score (ABSIS) aims to measure the phenotypical varieties seen across PV, with careful consideration of skin and mucosal involvement as separate entities with different significance [24]. The ABSIS skin score measures extent of affected area and quality of skin lesions. Extent is assessed by percent of involved BSA and the “rule of nine”. Quality is defined as re-epithelialized lesions (0.5), erosive dry lesions (1.0), or erosive, exudative lesions with or without a positive Nikolsky’s sign (1.5). The ABSIS skin score is calculated by multiplying the BSA by the appropriate quality weighting factor. Oral involvement is assessed separately and with two scores. The first score assesses extent with 0 for absence of or 1 for presence of lesions in 11 distinct anatomical locations. The second score measures severity based on quantitative dysphagia. A prospective trial is needed to assess the reliability and validity of the ABSIS.

Another outcome measure for PV, the pemphigus disease area index (PDAI), has recently been developed as a part of an international collaborative effort to create a universally accepted index of disease severity in PV. Validation studies took place in August 2007.

A single, validated outcome measure for PV is clearly needed and is currently being developed. However, collaborators must first agree on definitions of remission, including partial, complete and long-lasting remission. Definitions as to what constitutes a flare and/or a relapse must also be defined. An international effort to develop definitions of outcomes in pemphigus was initiated in 2005, after an NIH meeting on pemphigus. This effort is nearly completed. Parameters that most accurately measure disease severity in PV must be defined. In addition, skin and mucosal lesions need to be weighted appropriately.

Conclusions

There is a clear need for the development of validated outcome measures in refractory diseases that are difficult to treat. Not only is this imperative for treatment purposes, but it is also important for systematically evaluating the disease process. The cutaneous manifestations of LE and DM are among the least systematically studied largely due to the fact that validated disease scoring systems did not exist until recently. Much information about disease progression and signs of improvement is lacking in the absence of tools used to monitor disease severity.

First and foremost, collaborative efforts must be made to develop tools that best capture the disease process. When appropriate, collaboration on the development and use of clinical outcome measures must span across different specialties, namely dermatology and rheumatology.

There is a need for disease specific scoring systems that are quick, easy to perform, reliable and valid for classifying disease severity. With the advent of these tools, clinical trials may be carried out in hopes of improving treatments options.

References

- 1.Albrecht J, Taylor L, Berlin J et al (2005) The CLASI (cutaneous lupus erythematosus disease area severity and index): an outcome instrument for cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol 125:889–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Albrecht J, Werth VP (2007) Development of the CLASI as an outcome instrument in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Ther 20:93–101 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Beissert S, Werfel T, Frieling U, Bohm M, Sticherling M, Stadler R, Zillikens D, Rzany B, Hunzelmann N, Meurer M, Gollnick H, Ruzicka T, Pillekamp H, Junghans V, Luger TA (2006) A comparison of oral methylprednisolone plus azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil for the treatment of pemphigus. Arch Dermatol 142(11):1447–1454 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bombaridier C, Gladmann DD, Urowitz MB et al (1992) Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The committee on prognosis studied in SLE. Arthritis Rheum 35(6):630–640 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Bonilla-Martinez Z, Albrecht J, Taylor L, Okawa J, Dulay S, Werth V (2007) The CLASI is a responsive instrument to measure activity and damage in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) (2005) Systemic lupus erythematosus—developing drugs for treatment (Guidance for Industry—Draft). http://www.fda.gov/CDER/guidance/6496dft.htm. Accessed 24 March 2007

- 7.Charman C, Williams H (2000) Outcome measures of disease severity in atopic eczema. Arch Dermatol 136:763–769 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC (1999) Measurement of body surface area involvement in atopic eczema: an impossible task? Br J Dermatol 140:109–111 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Cook CH, Centner RL, Michaels SE (1979) An acne grading method using photographic standards. Arch Dermatol 115:571–575 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Concept paper systematic lupus erythematosus 09/16/2003. 1-4-1901 (Pamplet)

- 11.Feldman SR, Krueger GG (2005) Psoriasis asseessment tools in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 64 (Suppl II):ii65–ii68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Finlay AY (1996) Measurement of disease activity and outcome in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 135:509–515 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Finlay AY, Kelly SE (1987) Psoriasis—an index of disability. Clin Exp Dermatol 12:8–11 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Ong A et al (1996) A comparison of five health status instruments in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Lupus 5(3):190–195 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hahn B, Chuang TY (2006) Using the dermatology index of disease severity (DIDS) to assess the responsiveness of dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 31(1):19–22 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Klein RQ, Bangert CC, Costner M et al (2007) Comparison of the reliability and validity of outcome instruments for cutaneous dermatomyositis. J Invest Dermatol 127:359 (Abstract #249) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Krathen MS et al (2007) The cutaneous lupus erythematosus disease area severity and index (CLASI) reliability and validity assessment: expansion for rheumatology and dermatology and evaluation with spectroscopy. J Invest Dermatol 127:S8 (Abstract #48)

- 18.Kunz B, Oranje AP, Labrèze L, Stalder JF, Ring J, Taïeb A (1997) Clinical validation and guidelines for the SCORAD index: consensus report of the European task force on atopic dermatitis. Dermatology 195(1):10–19 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Lucky AW, Barber BL, Girman CJ, Williams J, Ratterman J, Waldstreicher J (1996) A multirater validation study to assess the reliability of acne lesion counting. J Am Acad Dermatol 35:559–565 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Mentink LF, Mackenzie MW, Gabor G et al (2006) Randomized controlled trial of adjuvant oral dexamethasone pulse therapy in pemphigus vulgaris. Arch Dermatol 142:570 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Njoo MD, Das PK et al (1999) Association of the Koebner phenomenon with disease activity and therapeutic responsiveness in vitiligo vulgaris. Arch Dermatol 135:407–413 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Parodi A, Massone C, Cacciapuoti M et al (2000) Measuring the activity of disease in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 142(3):457–460 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Plewig G, Jansen T (1999) Rosacea, Chap 74, pp 785–794 (Table 74-1, p 786). In: Freedburg IM, Eisen AZ et al (eds) Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine, 5th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York (1999)

- 24.Pfutze M, Niedermeier A, Hertl M, Eming R (2007) Introducing a novel autoimmune bullous skin disorder intensity score (ABSIS) in pemphigus. Eur J Dermatol 17(1):4–11 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Quain RD, Teal V, Taylor L, Werth VP (2007) Number, characteristics, and classification of dermatomyositis patients seen by dermatology and rheumatology at a tertiary medical center. J Invest Dermatol 127:S57 (Abstract #340) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Ramsay B, Lawrence CM (1991) Measurement of involved surface area in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 124:565–570 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Rider LG, Lachenbruch PA, Rennebohm RM et al (1995) Identifying skin lesions in dermatomyositis (DM): inter-rater reliability of a new cutaneous assessment tool (CAT). Arthritis Rheum 38(Suppl):S168

- 28.Rider LG, Feldman BM, Perez MD et al (2003) Development of validated disease activity and damage indices for the juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatology 42(4):591–595 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Singer AJ, Thode HC, Hollander JE (2000) Research fundamentals: selection and development of clinical outcome measures. Acad Emerg Med 7(4):397 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Sontheimer RD (1999) Cutaneous features of classic dermatomyositis and amyopathic dermatomyositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 11(6):475–482 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Sontheimer RD et al (2003) Cutaneous manifestations of rheumatic disease. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

- 32.Tebbe B, Orfanos CE (1997) Epidemiology and socioeconomic impact of skin disease in lupus erythematosus. Lupus 6:96–104 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Tiling-Grosse S, Rees J (1993) Assessment of area of involvement in skin disease: a study using schematic figure outlines. Br J Dermatol 128:69–74 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Urowitz MB, Gladmann DD, Tozman EC, Goldsmith CH (1984) The lupus activity criteria count (LACC). J Rheumatol 11(6):783–787 [PubMed]

- 35.Werth VP, Fivenson D, Pandya A, Chen D, Rico J, Albrecht J, Jacobus D (2005) Multicenter randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of dapsone as a glucocorticoid-sparing agent in maintenance phase pemphigus vulgaris. JID 125:1088 (abstract) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Williams HC (2003) Is a simple generic index of dermatologic disease severity an attainable goal? Arch Dermatol 139:1490 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Mrowietz U, Elder JT, Barker J (2006) The importance of disease associations and concomitant therapy for the long-term management of psoriasis patients. Arch Dermatol Res 298:309–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Sitaru C, Mihai S, Zillikens D (2007) The relevance of the IgG subclass of autoantibodies for blister induction in autoimmune bullous skin diseases. Arch Dermatol Res 299(1):1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]