Imaging abnormalities of the splenium of the corpus callosum (SCC) are uncommon but have been described in various clinical conditions such as Marchiafava‐Bignami disease, trauma, infectious diseases, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, epilepsy, altitude sickness, hypoglycaemia, electrolyte abnormalities, leukodystrophy, and infarction, and following radiation therapy and chemotherapy.1,2 We have detected a diffuse lesion in the SCC of two patients with methyl bromide intoxication.

Case report 1

The first case involved a previously healthy 31 year old man. He had worked in a fumigating plant spraying strawberries for 1 month prior to admission. Strawberries were fumigated with methyl bromide for 2 h in an enclosed room. After fumigation, the room was ventilated for 10 min with electric fans. Thereafter, the subject transferred the fumigated fruits to a warehouse. He worked for 3 h every other day. The subject reported experiencing intermittent nausea, dizziness, and ambulatory difficulty. On the day of hospital admission, the patient complained of general weakness, developed paraesthesia in the hands and feet, and was unable to recall daily events. He was admitted to the nearest hospital. The patient exhibited urinary incontinence, talked to himself, and was unable to walk unaided. He was transferred to our hospital 2 days later. Upon examination, all of the patient's vital signs proved normal. However, he attempted to grab phantom objects in the air, sucked his fingers, and had difficulty with speech comprehension. He received antiplatelet agents, vitamin B complex, and folic acid. The patient began to understand what was said to him 3 days after admission, although his comprehension of language was still defective. After 2 weeks of hospitalisation, he was discharged, and exhibited no further cognitive deterioration.

Laboratory tests of blood and cerebrospinal fluid excluded anaemia, electrolyte abnormalities, diabetes, hepatic and collagen diseases, syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus infection, encephalitis, and multiple sclerosis. Serum folate levels (3.4 nmol/l) were below normal. However, serum vitamin B12 and homocysteine levels were within normal limits.

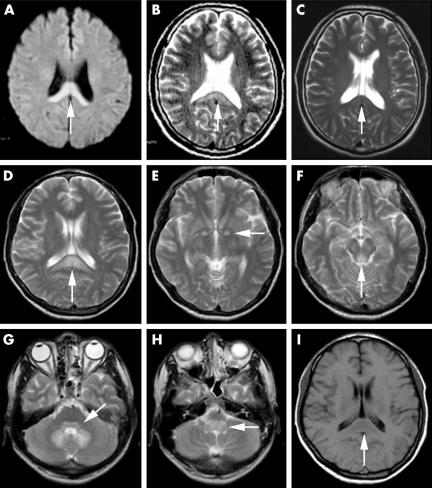

Electroencephalography revealed many mixed slow waves on all leads. Diffusion weighted imaging and T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) taken 1 day prior to transfer to our hospital revealed increased signal intensity of nearly the entire SCC (fig 1A,B). The lesions extended into the lateral portion of the SCC. These lesions were isointense on the T1 weighted images. No parenchymal enhancements were observed following intravenous administration of gadolinium contrast agents. T2 weighted images obtained 1 month after the detection of the lesions demonstrated they had nearly disappeared (fig 1C).

Figure 1 Axial diffusion weighted image from case 1 demonstrates an increased signal intensity area in the splenium of the corpus callosum (A). Axial T2 weighted magnetic resonance image demonstrates hyperintense lesions in the same region (B). Another T2 weighted image obtained 1 month later discloses near resolution of the lesions (C). T2 weighted axial image in case 2 shows bilateral symmetric high signal intensities in the splenium of the corpus callosum (D), the globus pallidus (E), the periaqueductal grey matter of the midbrain (F), the pontine tegmentum (G), the dentate nucleus (G), and the medulla oblongata (H). These lesions were hypointense on T1 weighted images (I).

Case report 2

Five days before the discharge of the first patient, a 32 year old man was admitted to the same hospital because of sudden dysarthria, headache, dizziness, and confusion. Prior to admission, this second patient had worked for 15 days in the same fumigation company as the previous subject. His job was to carry the fumigated strawberries to the warehouse. He had no history of severe head trauma, febrile convulsions, or encephalitis.

Upon examination, all of the patient's vital signs proved normal. The patient was confused, and both temporally and spatially disoriented. Mild dysarthria was also present. Tendon reflexes were hyperactive. Bilateral extensor plantar responses were present. Nuchal rigidity was absent. The patient became lethargic and 2 h after admission developed a generalised tonic‐clonic seizure, which resolved after intravenous administration of lorazepam. The patient was then treated with emergent haemodialysis daily for 3 days. He remained lethargic and irritable, and although he was aroused by speaking, he failed to respond to spoken commands. He attempted to sit up in bed and thrashed his limbs violently. His condition remained unchanged until hospital day 7 when he was transferred to another hospital at his family's request.

The following investigations were normal or negative: blood cell count, serum glucose, creatinine, serum electrolytes, thyroid function test, electrocardiogram, and chest roentgenogram. Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase level was 0.83 μkat/l and serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase was 2.08 μkat/l. Serum bromide concentration was a remarkable 0.412 mmol/l (normal: 0.028–0.065 mmol/l) on the third hospital day, as determined with ion chromatography.

T2 weighted brain MRI revealed bilateral symmetric high signal intensities in the SCC, the globus pallidus, the periaqueductal grey matter of the midbrain, the pontine tegmentum, the dentate nucleus, and the medulla oblongata (fig 1D–H). These lesions were hypointense on T1 weighted images (fig 1I). The shape of the SCC lesions was similar to that of case 1.

Discussion

Exposure to high concentrations of methyl bromide can result in gastrointestinal, neurological, and respiratory symptoms.3,4 The neuropathological alterations associated with methyl bromide intoxication include small subarachnoid haemorrhage, capillary proliferation, demyelination, degeneration of neurons, and gliosis. The sites of involvement include the cerebral cortex, quadrigeminal bodies, red nuclei, dentate and olivary nuclei, and the superior cerebellar peduncles.4 Ichikawa et al reported a case of methyl bromide intoxication involving bilateral symmetrical lesions on MRI in the putamen, the subthalamic nuclei, the dorsal medulla oblongata, the inferior colliculi, and the periaqueductal grey matter of the midbrain.5

Methyl bromide intoxication can be suspected on the basis of history of exposure, clinical findings, and results of laboratory studies. There are no reliable indicators of exposure to methyl bromide; due to its short half life, it rapidly becomes undetectable in human tissues, and serum bromide concentrations are considered to correlate poorly with clinical symptoms and outcome.3

To our knowledge, lesions confined to the SCC have not previously been reported in patients with methyl bromide poisoning. The imaging differential diagnosis of SCC abnormalities includes Marchiafava‐Bignami disease, trauma, infectious diseases, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, epilepsy, altitude sickness, neoplasia, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hypoglycaemia, electrolyte abnormalities, renal failure, leukodystrophy, infarction, and hypertension.1,2 In our cases, these diagnoses were excluded by both the clinical setting and the laboratory findings.

In conclusion, diffuse lesions in the SCC can be seen on MRI of patients with methyl bromide poisoning. If a patient with a splenial lesion is encountered, a detailed history regarding to their occupation and substance abuse should be obtained.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Ju‐Hwan Lee (Doctor of Dental Surgery), who is a brother of one of the patients, for helpful advice.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

Patient details are published with consent

References

- 1.Doherty M J, Jayadev S, Watson N F.et al Clinical implications of splenium magnetic resonance imaging signal changes. Arch Neurol 200562433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polster T, Hoppe M, Ebner A. Transient lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum: three further cases in epileptic patients and a pathophysiological hypothesis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 200170459–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hustinx W N M, Van de Laar R T H, Van Huffelen A C.et al Systemic effects of inhalational methyl bromide poisoning: a study of nine cases occupationally exposed due to inadvertent spread during fumigation. Br J Ind Med 199350155–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shield L K, Coleman T L, Markesbery W R. Methyl bromide intoxication: neurologic features, including simulation of Reye syndrome. Neurology 197727959–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ichikawa H, Sakai T, Horibe Y.et al A case of chronic methyl bromide intoxication showing symmetrical lesions in the basal ganglia and brain stem on magnetic resonance imaging. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 200141(7)423–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]