Abstract

Knowledge of human central taste pathways is largely based on textbook (anatomical dissections) and animal (electrophysiology in vivo) data. It is only recently that further functional insight into human central gustatory pathways has been achieved. Magnetic resonance imaging studies, especially selective imaging of vascular, tumoral, or inflammatory lesions in humans has made this possible. However, some questions remain, particularly regarding the exact crossing site of human gustatory afferences. We present a patient with a pontine stroke after a vertebral artery thrombosis. The patient had infarctions in areas supplied by the anterior inferior cerebellar artery and showed vertical diplopia, right sided deafness, right facial palsy, and transient hemiageusia. A review of the sparse literature of central taste disorders and food preference changes after strokes with a focus on hemiageusia cases is provided. This case offers new evidence suggesting that the central gustatory pathway in humans runs ipsilaterally within the pons and crosses at a higher, probably midbrain level. In patients with central lesions, little attention has been given to taste disorders. They may often go unnoticed by the physician and/or the patient. Central lesions involving taste pathways seem to generate perceptions of quantitative taste disorders (hemiageusia or hypogeusia), in contrast to peripheral gustatory lesions that are hardly recognised as quantitative but sometimes as qualitative (dysgeusia) taste disorders by patients.

Keywords: stroke, taste, pons, hemiageusia, brainstem

It is estimated that at least 1% of the American population suffers from taste problems.1 These may occur for several reasons, including systemic diseases, medication side effects or trophic/metabolic problems (such as xerostomia) within the oral cavity. However, most taste disorders are diagnosed as being idiopathic.1 Gustatory testing has not become routine in neurology and although several testing methods exist,2 it has remained the domain of specialised smell and taste investigation centres.

While the causes of peripheral taste disorders are well documented,1,3 central taste deficiencies have only recently been systematically investigated.4,5,6 Knowledge on human central taste pathways seems established, although it is mainly based on anatomical (dissections) and animal (in vivo electrophysiology) data.7 However, recent reports have given further functional insight into human central gustatory pathways. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies,8 particularly the investigation of selective vascular, tumoral, or inflammatory lesions in humans, has made this possible.4,5,9,10 According to these reports, it is obvious that human gustatory afferences cross to some extent; however, open questions remain, particularly regarding the exact crossing level of the these afferences.11,12 Moreover, non‐human primates and humans seem to exhibit distinct differences in gustatory brainstem connections compared with rodents.7

The aim of this case report and literature review was to highlight and discuss qualitative unilateral taste impairments (ageusia or hypogeusia) in patients with cerebrovascular lesions. Our patient presented a transient hemiageusia subsequent to a lateral pontine lesion, suggesting a predominantly ipsilateral gustatory brainstem pathway.

CASE REPORT

A 55 year old man, treated for hypercholesterinaemia without any other comorbidities, presented a sudden onset of rotation vertigo, sensation of being pulled to the right side, nausea, speech difficulties, occipital headache, vertical diplopia, right sided deafness, right facial weakness, and a feeling of numbness on the right side of the tongue with lowered taste perception on this side.

On admission, there was a right central facial palsy, spontaneous left beating nystagmus, dysarthria, complete right hearing loss, and right hemiataxia. Lateralised taste testing with taste strips (for details see Mueller et al2) consisting of filter paper strips impregnated with the four basic taste qualities2 showed ageusia of the right anterior two thirds of the tongue (score: 3 tastes identified of 16 presented) and normogeusia on the left side (score: 8 identified of 16 presented). Olfactory testing with “Sniffin' Sticks”13 revealed normosmia (threshold, discrimination, and identification (TDI) score 35.5). A pure tone audiogram showed complete sensorineural hearing loss of the right ear, and electronystagmography revealed a right caloric areflexia.

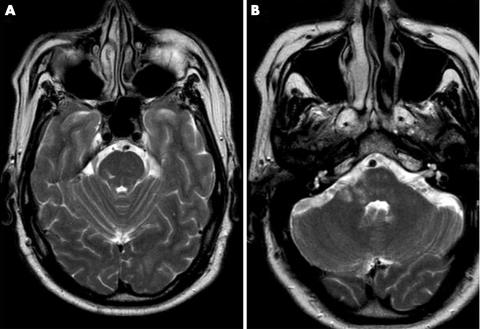

Computed tomography and MRI angiography showed an occluded right vertebral artery and magnetic resonance images showed high intensity areas within the right medial cerebellar peduncle, the right cerebellum and the right pontine tegmentum (fig 1A, B). Six months later, all symptoms except the hearing loss disappeared, and taste testing revealed bilateral normogeusia.

Figure 1 Magnetic resonance images showing a high intensity within (A) the right pons (T2 weighted sequence), and (B) the right middle cerebellar peduncle and the right cerebellum.

DISCUSSION

The main interest of this patient with central hemiageusia is twofold. Firstly, the present and previously reported cases suggest strongly that the crossing taste fibres have their decussation at a level above the pons, with some anatomical variability, most likely located in the midbrain. Secondly, it emphasises the puzzling fact that central lesions involving taste pathways seem to generate a perception of hemiageusia, while patients with peripheral taste loss are hardly ever aware of a quantitative gustatory deficit.

In rodents, as in non‐human primates and humans, peripheral taste fibres are carried within cranial nerves VII, IX, and X, and converge to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS).7 Second order gustatory fibres ascend ipsilaterally from the NTS towards the pons. In rodents, the crossing taste fibres form a synapse in the pontine parabrachial nucleus (rodent pontine taste area) and project to the ventroposterior medial nucleus of the thalamus (thalamic gustatory nucleus).7 In non‐human primates and humans, the crossing taste fibres are believed to join the pontine tegmentum, and further on the thalamic gustatory nucleus without forming a synapse in the pons. There is currently no evidence for a pontine taste relay (nucleus) in non‐human primates and humans. This seems to be corroborated by a recent functional MRI study,8 which was able to show NTS activity in humans during gustatory stimulation without recording any activity at the parabrachial level. Taste pathways im both non‐human primates and humans differ from those in rodents mainly in the brainstem/pontine crossing connections. While rodents have an additional relay nucleus to form the decussation, human and non‐human primate taste fibres cross without synapsing.

Anatomy textbooks propose that the human gustatory pathway ascends from the NTS via the medial leminiscus,11 whereas almost all recent case reports including ours (see table 1) seem to contradict this view. Based on these cases, it is more likely that ascending gustatory fibres cranial of the NTS travel more laterally within the medulla and pons. According to clinical reports (table 1), it is obvious that human gustatory afferences cross to some extent; however, there is still an open question regarding the precise crossing level of these taste fibres. Cases of hemiageusia after central lesions seem appropriate to help in locating the decussation of taste fibres in humans. However, reports on hemiageusia are sparse, and to our knowledge there are only 33 cases of unilateral taste losses reported due to cerebrovascular lesions (table 1), and a few more due to isolated multiple sclerosis plaques within the brain stem.14,15 In these cases it is thought that hemiageusia is due to disruption of ascending fibres rather that to cell body damage (which would imply a pontine taste relay nucleus). As the NTS, located within the medulla, extends almost to the lower pons, quantitative taste disorders might be much more frequently encountered in brain stem lesions than reported. In contrast to impressive symptoms such as vertigo, dysarthria, sensory disorders, and facial palsy, taste loss may simply go unnoticed by the patient or the physician.

Table 1 Overview of the reported cases with unilateral taste disorder after a stroke.

| Reference | Lesion | Side of taste disorder | No. of patients* | Taste tested | Taste disorder perceived | Taste reversible | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heckmann et al.4 | Pontine | Ipsilateral | Yes | No information | Yes | |||||||

| Supratentorial | Ipsilateral | 2 | ||||||||||

| Supratentorial | Contralateral | 3 | ||||||||||

| Onoda et al.5 | Pontine | Ipsilateral | 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Thalamic | Contralateral | 1 | ||||||||||

| Internal capsula | Contralateral | 1 | ||||||||||

| Jyoichi et al.5 | Pontine | Ipsilateral | 1 | Yes | No information | No information | ||||||

| Grant21 | Pontine and medulla | Ipsilateral | 1 | No | No information | No information | ||||||

| Ito et al.5 | Thalamic | Ipsilateral | 1 | Yes | No information | No information | ||||||

| Goto et al.22 | Pontine | Ipsilateral | 3 | Yes | Yes | No | ||||||

| Lee et al.12 | Pontine | Ipsilateral | 2 | Yes | Yes | No information | ||||||

| Midbrain | Contralateral | 1 | ||||||||||

| Nakajima et al.23 | Pontine | Ipsilateral | 1 | Yes | Yes | No information | ||||||

| Kim et al.20 | Frontal operculum | Ipsilateral | 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Sunada et al.11 | Pontine | Contralateral | 1 | Yes | Yes | No | ||||||

| Fujikane16 | Pontine | Contralateral | 1 | Yes | Yes | No information | ||||||

| Kojima et al.15 | Pontine | Ipsilateral | 1 | Yes | Yes | No information | ||||||

| Fujikane16 | Thalamic | Contralateral | 4 | Yes | Yes | No information | ||||||

| Corona radiata | Contralateral | 3 | ||||||||||

| Shikama et al.17 | Midbrain | Ipsilateral | 2 | Yes | No information | No information | ||||||

| Pritchard et al.18 | Insula | Ipsilateral | 1 | Yes | No | No | ||||||

| Our case | Pontine | Ipsilateral | 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

*With unilateral taste disorder.

Summarising the cases (table 1) shows that human taste pathways cranial from the NTS run ipsilaterally within the pons. Thus, most pontine lesions cause ipsilateral taste losses, whereas higher (midbrain, thalamic, and insular) lesions either entail contralateral hemiageusia or bilateral hypogeusia. Occurrence and consciousness and of hemiageusia is much more frequent in medullar, pontine, and midbrain lesions than in thalamic lesions, suggesting the crossing to be somewhere between midbrain and thalamus.5,16 However, few cases with contralateral ageusia in pontine lesions and ipsilateral ageusia after midbrain lesions have been reported.11,16,17 One author also observed a thalamic lesion causing an ipsilateral hypogeusia, which could be an argument for uncrossed gustatory fibres.5 In contrast, most reports on thalamic or insular insults show bilateral taste alterations,9,10,15,18 suggesting some anatomical variability concerning the decussation site of gustatory fibres. Insular and orbitofrontal cortices, which are believed to be secondary and tertiary gustatory areas,7 almost always cause bilateral hypogeusia or hemiageusia of which the patient is unaware.18 In a recent prospective study, Heckmann et al4 found that 30% of patients with acute stroke, mostly with frontal lobe pathology, exhibited bilateral hypogeusia of which they were unaware. A recent paper by Mak et al19 also proposes a new hypothesis of taste perception consequences in insular lesions. Release of inhibition within the insula would account for increased taste intensity perception on the contralateral side of the lesion rather than decreased perception on the ipsilateral side. Thus, some previous reports18 might be reinterpreted (see Mak et al19 for details). Moreover, strokes in thalamic, insular, opercular, and right hemispheric regions not only altered the measurable taste function but also induced food preference changes, mostly food aversion.9,10,15,20 Hence, clinical data strongly suggest that gustatory fibres in humans cross cranial from the pons, most probably at the midbrain level.

The reviewed literature (table 1) shows that with one exception,18 in a patient with an insular infarct, all patients perceived and complained of lowered taste perception on one side of the tongue. This is surprising, as quantitative taste impairments (hypogeusia or ageusia) due to peripheral lesions of the gustatory nerves go unnoticed by most patients.3 Severing of the chorda tympani, which happens frequently in middle ear surgery, leads to complete ipsilateral ageusia, but remains unnoticed by the majority of patients.3 Peripheral lesions, as in facial palsy, occasionally produce transient qualitative taste disorders (dysgeusia, most often metallic taste), but are rarely perceived as quantitative taste loss and hardly ever localised within the tongue. As trigeminal and gustatory fibres co‐innervate the tongue, these perceived “hemiageusias” could be due to ipsilateral trigeminal nucleus lesions rather than being taste specific. However, a case of perceived and measured hemiageusia, in a patient with a very small lesion sparing the trigeminal nuclei and without any sensory alterations, argues against this assumption.14

Taken together, these findings suggest that perceived hemiageusia, especially associated with other delimited neurological deficits, should alert clinicians to think of a central, most likely pontine involvement of gustatory pathways.

Our patient showed an occluded right vertebral artery with lesions in the pontine tegmentum, right cerebellum, and right middle cerebellar peduncle, explaining most of his symptoms. All symptoms, except the right sided deafness, disappeared with time. We believe the deafness and caloric areflexia to be due to a peripheral, probably embolic event within the anterior inferior cerebellar artery or its branch the internal auditory artery.24 This would explain the audiometric findings in our patient, as pure tone losses are unusual for central lesions.24

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Fund for Scientific Research FNSRS (no. 3100A0‐100621‐1) to J‐S Lacroix. We would like to thank Dr C Mueller from the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at the University of Vienna for helpful advice concerning production and use of the taste strips.

Abbreviations

MRI - magnetic resonance imaging

NTS - nucleus tractus solitarius

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Bromley S M, Doty R L. Clinical disorders affecting taste: Evaluation and management. In: Doty RL, ed. Handbook of olfaction and gustation. 2nd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc, 2003935–958.

- 2.Mueller C, Kallert S, Renner B.et al Quantitative assessment of gustatory function in a clinical context using impregnated “taste strips”. Rhinology 2003412–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saito T, Manabe Y, Shibamori Y.et al Long‐term follow‐up results of electrogustometry and subjective taste disorder after middle ear surgery. Laryngoscope 20011112064–2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heckmann J G, Stossel C, Lang C J.et al Taste disorders in acute stroke: a prospective observational study on taste disorders in 102 stroke patients. Stroke 2005361690–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onoda K, Ikeda M. Gustatory disturbance due to cerebrovascular disorder. Laryngoscope 1999109123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heckmann J G, Heckmann S M, Lang C J.et al Neurological aspects of taste disorders. Arch Neurol 200360667–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rolls E T, Scott T R. Central taste anatomy and neurophysiology. In: Doty RL, ed. Handbook of olfaction and gustation. 2nd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc, 2003679–705.

- 8.Topolovec J C, Gati J S, Menon R S.et al Human cardiovascular and gustatory brainstem sites observed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Comp Neurol 2004471446–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finsterer J, Stollberger C, Kopsa W. Weight reduction due to stroke‐induced dysgeusia. Eur Neurol 20045147–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rousseaux M, Muller P, Gahide I.et al Disorders of smell, taste, and food intake in a patient with a dorsomedial thalamic infarct. Stroke 1996272328–2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sunada I, Akano Y, Yamamoto S.et al Pontine haemorrhage causing disturbance of taste. Neuroradiology 199537659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee B C, Hwang S H, Rison R.et al Central pathway of taste: clinical and MRI study. Eur Neurol 199839200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobal G, Klimek L, Wolfensberger M.et al Multicenter investigation of 1,036 subjects using a standardized method for the assessment of olfactory function combining tests of odor identification, odor discrimination, and olfactory thresholds. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2000257205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uesaka Y, Nose H, Ida M.et al The pathway of gustatory fibers of the human ascends ipsilaterally in the pons. Neurology 199850827–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathy I, Dupuis M J, Pigeolet Y.et al Ageusie bilatérale après accident vasculaire cérébral ischémique insulaire et operculaire gauche. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2003159563–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujikane M, Itoh M, Nakazawa M.et al Cerebral infarction accompanied by dysgeusia—a clinical study on the gustatory pathway in the CNS. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 199939771–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shikama Y, Kato T, Nagaoka U.et al Localization of the gustatory pathway in the human midbrain. Neurosci Lett 1996218198–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pritchard T C, Macaluso D A, Eslinger P J. Taste perception in patients with insular cortex lesions. Behav Neurosci 1999113663–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mak Y E, Simmons K B, Gitelman D R.et al Taste and olfactory intensity perception changes following left insular stroke. Behav Neurosci 20051191693–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J S, Choi S. Altered food preference after cortical infarction: Korean style. Cerebrovasc Dis 200213187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant G. Infarction localization in a case of Wallenberg's syndrome. A neuroanatomical investigation with comments on structures responsible for nystagmus, impairment of taste and deglutition. J Hirnforsch 19668419–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goto N, Yamamoto T, Kaneko M.et al Primary pontine hemorrhage and gustatory disturbance: clinicoanatomic study. Stroke 198314507–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakajima Y, Utsumi H, Takahashi H. Ipsilateral disturbance of taste due to pontine haemorrhage. J Neurol 1983229133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oas J G, Baloh R W. Vertigo and the anterior inferior cerebellar artery syndrome. Neurology 1992422274–2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]