A 53 year old man was stung behind the knees by five wasps, subsequently identified as belonging to the species Vespula germanica (commonly known as “yellow jackets”). Within a few minutes, he became dizzy, began to wheeze, and collapsed. He responded rapidly to intramuscular epinephrine administered by the attending paramedics, but showed a persistent sinus tachycardia during the subsequent hospital admission. Thus, when he was discharged the following day, he was put on sotalol for 1 week.

He had been stung by a wasp 1 year previously, suffering only extensive local swelling. There was no personal or family history of atopic disease or of reactions to ingested or topical allergens.

He remained free of symptoms for the next 5 weeks, but then developed rapid onset, severe, and painful muscular twitching throughout his limbs, profuse generalised sweating, and insomnia. For 3 weeks prior to his second hospital admission, he was treated with a combination of amitriptyline 10 mg nightly and gabapentin 300 mg thrice daily without effect.

On examination, the patient was afebrile but had hyperhidrosis and tachycardia. He appeared emotionally labile. There were continuous coarse fasciculations throughout all limbs, most markedly in the deltoid and quadriceps bilaterally. The limb tone was normal, with preserved power and normal sensation.

Serum creatine kinase (CK) level on admission was 10 756 IU/l. Serum urea and creatinine levels were normal and no urinary myoglobin was detected in laboratory analysis. The CK level returned to normal following 1 week of bed rest. Electromyography was characterised by spontaneous multiplet motor unit potential discharges with high intraburst frequency, typical of neuromyotonia. There was no evidence of polyneuropathy on nerve conduction study. Electroencephalography demonstrated poorly sustained 8 Hz alpha rhythm with posterior delta slow wave activity. Cerebrospinal fluid examination demonstrated 2 leucocytes/mm3, protein 0.226 g/l and glucose 4.6 mmol/l (serum 6.3 mmol/l). No oligoclonal bands were detected. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and spinal cord, computed tomography scan of the chest and abdomen, and bone marrow aspiration were all normal.

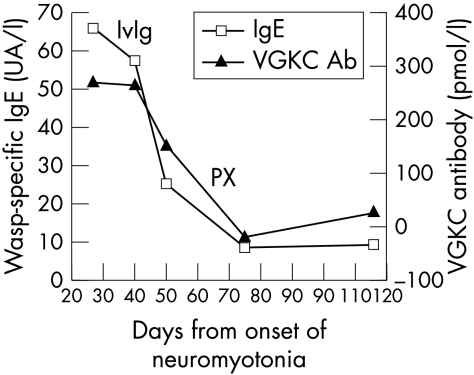

Antibodies to the voltage gated potassium channel (VGKC) were raised, with a titre of 340 pmol/l on admission, in conjunction with a wasp venom specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) level of class 5/6 measured by radioallergosorbent test. Acetylcholine receptor and antineuronal antibodies were not detected.

Electrocardiography revealed paroxysmal atrial tachycardia requiring temporary treatment with oral amiodarone and digoxin. In an attempt to treat the neuromyotonia, the patient received oral carbamazepine up to a dose of 400 mg twice daily for the first 2 weeks after admission, without effect. He was then given a 5 day course of intravenous immunoglobulin at a dose of 0.4 g/kg daily, also without effect. Methylprednisolone 1 g was then administered intravenously every day for 5 days, but the neuromyotonia persisted. Oral mexiletine was then commenced at a dose of 200 mg thrice daily for the following 2 weeks, without significant symptomatic relief. Finally, the patient underwent plasma exchange therapy over 5 days, which was coincident with his symptoms beginning to subside. Nearly 4 months after onset, the neuromyotonia, sweating, and insomnia had completely resolved. Amiodarone and digoxin therapy was withdrawn with no recurrence of the cardiac arrhythmia.

Levels of both VGKC antibodies and total IgE fell in parallel with the patient's clinical recovery over the following weeks (fig 1).

Figure 1 Graph showing the change in VGKC antibody and wasp venom specific IgE levels with time. The first measurements were taken approximately 3 weeks after the onset of fasciculations. There is a close relationship between the two indices, which matched the clinical recovery of the patient. The timing of immunoglobulin therapy and plasma exchange is also shown. VGKC, voltage gated potassium channel titre; IgE, immunoglobulin E titre; IvIg, intravenous immunoglobulin; PX, plasma exchange.

DISCUSSION

Our patient developed severe and refractory generalised neuromyotonia, with evidence of autonomic nervous system dysfunction, 5 weeks after apparent recovery from an anaphylactic reaction to multiple wasp stings. Both VGKC antibodies and wasp venom specific IgE levels were raised, and both fell in parallel with clinical recovery. We cannot be certain which of the treatment strategies, if any, were responsible for the eventual resolution of the condition in our patient; recovery may simply have reflected the natural course of a monophasic autoimmune process.

A delayed syndrome, consisting of central and peripheral nervous system demyelination with a relapsing and remitting course, was described in another patient also stung by a yellow jacket wasp (V. pennsylvanica).1 Cerebral infarction, acute inflammatory polyradiculoneuropathy, encephalomyeloradiculopathy, optic neuropathy, and atrial arrhythmias have all been described as relatively acute sequelae of stings from creatures of the wider order Hymenoptera. Isaacs referred to his (later eponymous) syndrome as one of “continuous muscle fibre activity”, though the term neuromyotonia has now become synonymous with spontaneous muscle fibre hyperactivity as a result of peripheral nerve hyperexcitability, frequently resulting in visible “undulating” myokymia such as that seen in our patient. The CK level is frequently found to be raised. There was no evidence for rhabdomyolysis in our patient.

Neuromyotonia is most frequently an acquired condition. It has been found associated with myasthenia gravis, and as a paraneoplastic entity associated with underlying thymoma and small cell lung carcinoma (11% and 6% of cases respectively in one series2), but there was no evidence for this in our patient. About 40% of cases are associated with antibodies to VGKCs that are present on peripheral nerves, with the hypothesis that the mechanism is one of failure to repolarise the distal motor nerve terminal, leading to hyperactivity.

Our patient also developed autonomic dysfunction with prominent hyperhidrosis, emotional lability, insomnia, and cardiac arrhythmia. The “maladie de Morvan” (or fibrillary chorea) has been used to describe neuromyotonia occurring with central nervous system features including insomnia, hallucinations, and hyperhidrosis.3 Cerebral imaging has been reported as normal, as in the present case. Others have detected oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid, not found in the present case. VGKC antibodies have been frequently demonstrated in reported cases of Morvan's syndrome, and in a form of limbic encephalitis,4 suggesting that they may be present in a spectrum of neurological conditions.

Acute focal myokymia has been reported in relation to the venom of the timber5 and Mojave rattlesnakes. We postulate that the delayed onset syndrome in our patient was due to the development, during the 4 week period after the stings, of underlying VGKC antibodies—that is, an autoimmune, hypersensitivity‐type response to an unidentified antigen of the many found in the venom of yellow jacket wasps,6 possibly sharing epitopes with human VGKCs. The parallel decline in the IgE and VGKC antibody titres with clinical improvement provides limited evidence in support of this hypothesis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are indebted to the patient's wife for successfully capturing the wasps and thereby enabling their identification.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The department of clinical neurology provides a service for VGKC antibody testing and receives royalties from commercial tests.

References

- 1.Means E D, Barron K D, Van Dyne B J. Nervous system lesions after sting by yellow jacket. A case report. Neurology 197323881–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart I K, Maddison P, Newsom‐Davis J.et al Phenotypic variants of autoimmune peripheral nerve hyperexcitability. Brain 20021251887–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loscher W N, Wanschitz J, Reiners K.et al Morvan's syndrome: clinical, laboratory, and in vitro electrophysiological studies. Muscle Nerve 200430157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent A, Buckley C, Schott J M.et al Potassium channel antibody‐associated encephalopathy: a potentially immunotherapy‐responsive form of limbic encephalitis. Brain 2004127701–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brick J F, Gutmann L, Brick J.et al Timber rattlesnake venom‐induced myokymia: evidence for peripheral nerve origin. Neurology 1987371545–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman D R. Allergens in hymenoptera venom. V. Identification of some of the enzymes and demonstration of multiple allergens in yellow jacket venom. Ann Allergy 197840171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]