Pathophysiological mechanisms of ischaemic strokes occurring in patients with Rendu‐Osler‐Weber (ROW) disease remain unclear. We report on the case of a patient with ROW disease and pulmonary arteriovenous fistula thrombosis who suffered from recurrent strokes.

Case report

In January 2005, a 38 year old woman was referred for the first time to our hospital for an ischaemic stroke fifteen days after undergoing a medically induced abortion. She reported recurrent epistaxis during her two pregnancies (1993 and 1994) and two familial cases of Rendu‐Osler‐Weber (ROW) disease. She also had experienced two episodes of ischaemic stroke (January 1996 and December 1997). Stroke workup had only revealed a patent foramen ovale with atrial septal aneurysm, which had been surgically closed after the second stroke. She had been receiving aspirin since closure of the foramen ovale.

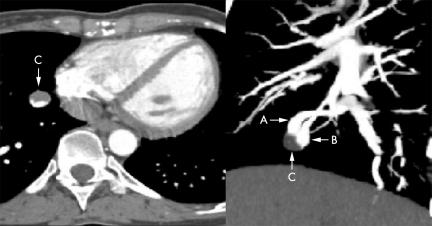

Eight years after the procedure, she presented with a new ischaemic stroke in the right middle cerebral artery territory, confirmed by brain diffusion weighted sequence magnetic resonance imaging. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. Cervical and transcranial ultrasonography, 12‐lead ECG, 24‐hour ECG monitoring, and chest radiography were normal. Routine blood tests and thrombophilia study (including tests for protein C, protein S, antithrombin III, factor V Leiden, factor II, hyperhomocysteinaemia, and antiphospholipid antibodies) did not show any abnormality. Contrast transoesophageal echocardiography (C‐TOE) revealed no atrial residual shunt, but a massive appearance of contrast bubbles in the left atrium from pulmonary veins. Chest 16‐slice multidetector computed tomographic (CT) angiography (Sensation 16, Siemens) with injection of 90 ml of contrast medium (Xenetix 350) at a rate of 4 ml/s using the “bolus tracking” technique was carried out. Helical CT data were acquired with a pitch of 0.75, 160 mAs, and 120 kV, and images were reconstructed with a slice thickness of 1 mm and interval of 0.5 mm. Multi‐planar reconstruction and maximum intensity projection images showed multiple pulmonary arteriovenous fistulae (PAVFs), consistent with ROW disease: two PAVFs in the right lower and apical lobes and two in the lingual and the left lower lobe. A thrombus was found in the PAVF located in the paracardiac segment of the right lower lobe (fig 1). Lower limbs and inferior vena cava ultrasonography did not reveal any venous thrombosis. Warfarin was started, and a new chest CT done one month later showed complete resolution of the intra‐fistula thrombus. Catheter embolisation of all PAVFs was then successfully undertaken.

Figure 1 Chest 16‐slice computed tomography, showing the thrombosis of a pulmonary arteriovenous fistula (C) and efferent (A) and afferent (B) vessels.

Comment

ROW disease, also called hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia, is an inherited autosomal dominant vascular dysplasia.1 Currently, it remains a clinical diagnosis based on two or more of the following manifestations: epistaxis, telangiectasia, a family disorder, or documented visceral involvement such as PAVF.1 PAVFs are found in approximately 15–20% of patients with ROW disease. They progressively enlarge and usually become symptomatic in adult life.2 PAVFs can be suspected on contrast transoesophageal echocardiography.3 However, as in our case, when a patent foramen ovale coexists with PAVF the early passage of contrast bubbles through the foramen ovale may prevent the contrast echocardiography from identifying the concomitant PAVF.

PAVFs are the most frequent cause of cerebral ischaemic events and brain abscesses in patients with ROW disease. Maher et al4 showed that stroke or transient ischaemic attacks occur in 30% of such patients with PAVF. The risk of stroke may be increased in patients with multiple PAVFs.5 However, the pathophysiology of these events remains unclear. A role of polycythaemia (resulting from chronic hypoxaemia) or air embolism has been suggested but never well documented.2 In fact, paradoxical embolisation through a right to left shunt caused by PAVF is probably the main mechanism for cerebral ischaemic events in ROW patients5; however, the source of embolism is rarely found. Indeed, conventional diagnostic techniques may fail to detect a small thrombus, particularly when located in some areas such as the pelvis or because thrombus has totally migrated when the stroke occurs.6 Although, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that PAVF thrombus resulted from peripheral embolism, our case suggests that PAVF may constitute a site of thrombosis. A slowing of blood flow through the fistula and a thrombotic state after abortion are two conditions that may have favoured in situ thrombosis in our case. To our knowledge, such a complication had never been documented before.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Shovlin C L, Guttmacher A E, Buscarini E.et al Diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu‐Osler‐Weber syndrome). Am J Med Genet 20009166–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roman G, Fisher M, Perl D P.et al Neurological manifestations of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu‐Osler‐Weber disease): report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Ann Neurol 19784130–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chessa M, Drago M, Krantunkov P.et al Differential diagnosis between patent foramen ovale and pulmonary arteriovenous fistula in two patients with previous cryptogenic stroke caused by presumed paradoxical embolism. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 200215845–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maher C O, Piepgras D G, Brown R D.et al Cerebrovascular manifestations in 321 cases of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Stroke 200132877–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moussouttas M, Fayad P, Rosenblatt M.et al Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: cerebral ischemia and neurologic manifestations. Neurology 200055959–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lethen H, Flachskampf F A, Schneider R.et al Frequency of deep vein thrombosis in patients with patent foramen ovale and ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. Am J Cardiol 1997801066–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]