Abstract

Background

Despite corticosteroid treatment, patients with temporal arteritis may continue to lose vision. However, predictors of progressive visual loss are not known.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 341 consecutive patients with suspected temporal arteritis who underwent temporal artery biopsy. 90 patients with biopsy proven temporal arteritis were included in our study.

Results

Twenty‐one patients (23%) experienced continuous visual symptoms despite steroid therapy and 14 among these suffered persistent visual deterioration. Based on univariate analysis, visual loss on presentation was associated with disc swelling and a history of hypertension. Risk factors for progressive visual loss included older age, elevated C reactive protein and disc swelling.

Conclusion

Although corticosteroid therapy improves the visual prognosis in temporal arteritis, steroids may not stop the progression of visual loss. Our study reliably establishes the risk factors for visual loss in this serious condition. Whether addressing these risk factors early in their presentation can alter the visual outcome remains unknown. Individual risk anticipating treatment regimens and strategies might improve the visual prognosis in temporal arteritis in the future.

Left untreated, temporal arteritis (TA) frequently results in blindness. Treatment requires immediate high dose steroids. Risk factors for initial and progressive visual loss, despite appropriate treatment, have not been extensively characterised, making selection of patients at risk for progressive visual loss difficult.

We retrospectively reviewed clinical findings in patients with biopsy proven TA in order to assess risk factors for visual loss during the first days of steroid therapy.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of 341 patients with suspected TA undergoing temporal artery biopsy during 15 consecutive years at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, UK, was performed.

Biopsies were performed on the side of predominant symptoms. Biopsies were deemed positive for TA if the histological specimen demonstrated arteritis, characterised by mononuclear cell arterial wall infiltration and interruption of the internal lamina elastica. Additional evidence included media degeneration or intima thickening.1 Visual acuity was expressed as a decimal (20/20 = 1.00; finger counting = 0.012; hand motion = 0.006; light perception = 0.001; no light perception = 0).2 In order to compare steroids among patients, the doses in patients receiving a steroid other than hydrocortisone were converted according to the following dosing scheme: 1 mg dexamethasone = 30 mg hydrocortisone; 1 mg methylprednisolone = 5 mg hydrocortisone, 1 mg prednisone = 4 mg hydrocortisone.

SPSS10.0 was used for statistical analysis. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Ninety‐three (27%) out of 341 biopsy results confirmed TA. Ninety patients (67 females; mean age 74.6 (SD 7.8); range 59–93) were included. The remaining three notes were lost.

Onset of symptoms prior to admission ranged from 2 days to 7 years (median 125 days). It took a median of 8 days (0–242 days) from referral until admission. Median duration of hospital stay was 11 days (0–53). Ninety‐one per cent of biopsies were performed within 5 days of admission; 71% were biopsied within 5 days after starting steroids. Five patients underwent temporal artery biopsy prior to initiation of steroids. All 90 biopsies were suggestive of TA. Fifty‐six (62%) biopsies showed giant cells.

Eighty‐nine patients received corticosteroids. One patient presented 3 weeks after blindness had occurred and was not treated. Thirty‐three patients initially received intravenous corticosteroid treatment (hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone or prednisolone). Fifty‐six patients were initially treated with prednisone by mouth. Doses were converted to hydrocortisone strength for comparison. The average initial corticosteroid dose consisted of 495 mg of hydrocortisone (range 0–5000). The average time until first dose taper was 21 days. In 31 patients, initial corticosteroid dose was increased in order to control symptoms completely.

Twenty‐one (23%) patients showed progressive visual symptoms despite corticosteroid therapy. A total of 20 patients suffered visual loss. Thirteen patients suffered persistent loss of acuity or field loss and one additional patient presented with a hemiparesis and diplopia (table 1). Deterioration occurred usually within the first days of treatment. Seven additional patients had transient visual impairment.

Table 1 Fourteen patients with loss of visual acuity/fields despite corticosteroid therapy.

| Patient No | Sex | Age (years) | History of present illness | Visual acuities on admission | Therapy prior to deterioration | Outcome of visual acuities | Time after therapy started (days) | 2 eyes involved | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OD | OS | OD | OS | ||||||||

| 1 | F | 78 | Visual loss OS since 2 days | 0.25 | 0.033 | 60 mg PD po | 0.012 | 0.006 | 5 | Yes | |

| 2 | F | 79 | Smeary vision OS since 4 days | 0.66 | 0.5 | 200 mg HC iv, 40 mg PD po | 0.66 | 0.006 | 1 | No | |

| 3 | F | 88 | Visual loss OS same day | 0.333 | 0.006 | 100 mg HC iv, 60 mg PD po | 0.333 | 0 | 1 | No | |

| 4 | F | 82 | Visual loss OS same day | 0.1 | 0.001 | 200 mg HC iv, 60 mg PD po | 0.1 | 0 | 2 | No | |

| 5 | F | 88 | Visual loss OU same day | 0 | 0.166 | 8 mg DM iv, 80 mg PD po | 0 | 0.001 | 1 | Yes | |

| 6 | F | 82 | Previous PMR 3 years ago, off steroids, OD blind 3 weeks ago, OS misty since 3 days | 0.001 | 0.001 | 200 mg HC iv, 500 mg MP iv x 3 days; then 80 mg PD po | 0 | 0 | 6 | Yes | |

| 7 | M | 64 | Sensory loss right forearm 3 weeks ago, double vision since 2 weeks, mild right hemiparesis since 1 day | 0.666 | 0.666 | 80 mg PD po | 0.333 | 0.666 | 2 | No | |

| 500 mg MP iv | 0.25 | 0.666 | 5 | ||||||||

| 120 mg PD po | 0.166 | 0.666 | 8 | ||||||||

| 80 mg PD po | Hemiparesis deteriorated | 12 | |||||||||

| 8 | F | 92 | Loss of vision OD 14 days ago | 0.001 | 0.666 | 60 mg PD po | 0 | 0.666 | 1 | No | |

| 9 | F | 75 | Visual loss OD since 1 day | 0.5 | 1.0 | 60 mg PD po | 0.001 | 1.0 | 2 | No | |

| 10 | M | 87 | Visual loss OD 6 days ago | 0.006 | 1.0 | 500 mg MP iv x 3 days; then 80 mg PD po | 0.001 | 0.012 | 3 | Yes | |

| 80 mg PD po | 0.012 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||

| 11 | F | 80 | Visual loss OD 2 weeks ago, blurred vision OS since 4 days | 0.001 | 0.666 | 500 mg MP iv x 3 days; then 80 mg PD po | 0.012 | 0.001 | 1 | Yes | |

| 80 mg PD po | 0 | 0 | 10 | Yes | |||||||

| 12 | F | 75 | OS blind 6 days ago, visual loss OD same day | 0.05 | 0 | 1000 mg MP iv x 3 days; then 80 mg PD po | 0 | 0 | 3 | Yes | |

| 13 | F | 59 | Black spot OS since 2 days, visual loss OS same day | 1.2 | 0.006 | 80 mg PD po | 0.666; scotoma | 0.012 | 2 | Yes | |

| 80 mg PD po | 0.666; enlarged scotoma | 0.012 | 27 | ||||||||

| 14 | F | 77 | PMR since 3.5 years, visual loss OS 6 months ago, visual loss OD 2 weeks ago | 0.016 | 0.166 | 1000 mg MP iv x 3 days; then 80 mg PD po | 0.012 | 0.1 | 7 | Yes | |

DM, Dexamethasone; HC, hydrocortisone; iv, intravenous; MP, methylprednisolone; OD, right eye; OS, left eye; OU, both eyes; PD, prednisolone; PMR, polymyalgia rheumatica; po, by mouth.

Of the seven patients with transient visual impairment despite corticosteroids, four patients had transient visual loss, one patient had an episode of left sided weakness and left visual loss, one patient complained about visual teichopsia and one patient developed disc swelling. All symptoms resolved after an increase in steroid dose.

The presence of disc swelling, history of hypertension and older age were significantly associated with visual loss on presentation. A trend of higher odds for initial visual loss was also seen in patients with polymyalgia, diabetes and jaw claudication (table 2). Patients with visual loss on presentation had a higher systolic blood pressure on presentation (table 3).

Table 2 Risk factors for initial visual loss: dichotomous variable.

| Dichotomous variable | Sign present (%) | Symptoms/sign absent (%) | χ2 p value | OR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disc swelling | 97.6 | 47.9 | 0.000 | 44.56 | 5.66–350.7 |

| Hypertension | 81.8 | 60.9 | 0.028 | 2.89 | 1.10–7.62 |

| Polymyalgia | 84.2 | 67.6 | 0.156 | 2.56 | 0.68–9.66 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 75 | 70.9 | 0.86 | 1.23 | 0.12–12.39 |

| Jaw claudication | 72.3 | 69.8 | 0.788 | 1.13 | 0.46–2.82 |

| Diplopia | 70 | 71.4 | 0.901 | 0.93 | 0.31–2.77 |

| Giant cells on biopsy | 69.6 | 73.5 | 0.693 | 0.83 | 0.32–2.14 |

| Cholesterol | 100 | 78.6 | 0.605 | 0.79 | 0.6–1.03 |

| Muscle tenderness | 67.6 | 73.6 | 0.535 | 0.75 | 0.30–1.88 |

| Male sex | 66.7 | 73.7 | 0.479 | 0.714 | 0.281–1.82 |

| Stroke | 60 | 71.8 | 0.573 | 0.59 | 0.09–3.76 |

| Systemic features | 63.6 | 78.3 | 0.126 | 0.49 | 0.19–1.23 |

| Temple tenderness | 63.6 | 78.3 | 0.126 | 0.49 | 0.19–1.23 |

| Smoker | 60.5 | 78.8 | 0.058 | 0.41 | 0.16–1.04 |

| Headache | 67.5 | 92.3 | 0.068 | 0.17 | 0.02–1.41 |

Table 3 Risk factors for initial visual loss: continuous variables.

| Continuous variable | Mean value in patients with visual loss (n) | Mean value in patients without visual loss (n) | t test p value | OR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood glucose (mg/dl) | 160 (59) | 144 (22) | 0.272 | 1.22 | 1.02–1.46 |

| Age (y) | 76.6 (64) | 69.5 (26) | 0.000 | 1.15 | 1.07–1.24 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 156 (64) | 145 (26) | 0.056 | 1.02 | 1.0–1.04 |

| ESR at referral (mm) | 75 (54) | 66 (18) | 0.213 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.04 |

| Onset (days) | 140 (63) | 88 (26) | 0.51 | 1.0 | 0.998–1.00 |

| Platelets at presentation | 457 (50) | 448 (17) | 0.831 | 1.0 | 0.997–1.0 |

| Corticosteroid dose (mg HC) | 672 (64) | 245 (26) | 0.004 | 1 | 1.00–1.00 |

| Time referral to admission (days) | 9 (61) | 6 (24) | 0.289 | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 |

| ESR at presentation (mm/h) | 70 (26) | 68 (63) | 0.779 | 0.996 | 0.98–1.01 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 82 (64) | 84 (26) | 0.422 | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 |

| Duration of hospital stay | 12 (64) | 9 (26) | 0.363 | 1.03 | 0.97–1.09 |

BP, blood pressure; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HC, hydrocortisone.

Risk factors for progressive visual loss included older age, elevated C reactive protein (CRP) and disc swelling (tables 4 and 5). Fourteen patients with early progressive visual loss despite corticosteroid therapy were, on average, 79.4 years old. Seventy‐six patients without progressive visual loss were, on average, 73.7 years old and therefore significantly younger (p<0.05, t test value 2.2). The CRP of patients with progressive visual loss was, on average, significantly higher (57.4; n = 7) than that of patients without visual loss (22.1; n = 12; p<0.02, t test value −3.0). Other factors significantly (p<0.05) associated with progressive visual loss were disc swelling (odds ratio (OR) 5.3 (95% CI 1.4 to 20.7)) and administration of steroids intravenously (OR 5.6 (95% CI 1.6 to 19.9)) (tables 4 and 5). Men had reduced odds of visual loss progression (OR 0.24 (95% CI 0.05 to 1.2)), approaching statistical significance (p = 0.06) (tables 4 and 5).

Table 4 Odds ratios for progressive visual loss: dichotomous symptoms.

| Symptom (dichotomous) | Symptom in patients with progressive loss (%) | Symptom in patients without progressive visual loss (%) | χ2 p value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV steroids | 30.3 | 7.1 | 0.004 | 5.65 | 1.6–19.91 |

| Disc swelling | 26.2 | 6.3 | 0.009 | 5.32 | 1.37–20.66 |

| Stroke | 40 | 14.1 | 0.121 | 4.06 | 0.61–26.86 |

| Headache | 16.9 | 7.7 | 0.398 | 2.44 | 0.29–20.42 |

| Scalp tenderness | 20.5 | 10.9 | 0.21 | 2.11 | 0.65–6.81 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 25 | 15.1 | 0.498* | 1.87 | 0.18–19.41 |

| Systemic symptoms | 18.2 | 13.0 | 0.501 | 1.48 | 0.47–4.68 |

| Hypertension | 18.2 | 13 | 0.501 | 1.48 | 0.47–4.68 |

| Muscle tenderness | 16.2 | 15.1 | 0.885 | 1.09 | 0.34–3.45 |

| Polymyalgia | 15.8 | 15.5 | 0.609* | 1.02 | 0.25–4.11 |

| Cholesterol by history | 0 | 14.3 | 0.867* | 0.86 | 0.69–1.06 |

| Giant cells on biopsy | 14.3 | 17.6 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 0.24–2.47 |

| Jaw claudication | 12.8 | 18.6 | 0.445 | 0.64 | 0.2–2.02 |

| Diplopia | 10 | 17.1 | 0.35* | 0.537 | 0.11–2.63 |

| Smoker | 7.9 | 21.2 | 0.086 | 0.32 | 0.08–1.24 |

| Male sex | 6.1 | 21.1 | 0.059 | 0.242 | 0.051–1.16 |

*Fisher's exact test.

Table 5 Odds ratios for progressive visual loss: continuous symptoms.

| Symptom (continuous) | Mean value in patients with progressive loss (n) | Mean value in patients without progressive visual loss (n) | t test p value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP on presentation | 57.43 (7) | 22.17 (12) | 0.016 | ||

| Age (y) | 79.41 (14) | 73.7 (76) | 0.042 | 1.1147 | 1.0208–1.2171 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 155.8 (14) | 154.5 (67) | 0.297 | 1.0699 | 0.9009–1.2707 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 86.79 (14) | 82.25 (76) | 0.066 | 1.0371 | 0.9839–1.0932 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 159.64 (14) | 152.15 (76) | 0.305 | 1.0118 | 0.9894–1.0347 |

| ESR at referral (mm/h) | 77.92 (13) | 71.90 (59) | 0.466 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 |

| Time referral to admission (days) | 18.29 (14) | 6.18 (71) | 0.497 | 1.0093 | 0.9941–1.0247 |

| ESR at presentation (mm/h) | 70.79 (14) | 67.70 (76) | 0.671 | 1.0044 | 0.9830–1.0263 |

| Platelets at presentation | 463.36 (11) | 453.79 (56) | 0.854 | 1.0004 | 0.9962–1.0047 |

| Steroid dose (mg HC) | 780 (14) | 479.21 (76) | 0.437 | 1.0002 | 0.9998–1.0007 |

| Onset of symptoms (days) | 109.36 (14) | 128.35 (75) | 0.681 | 0.9997 | 0.9975–1.0020 |

| Length of hospital stay | 21.57 (14) | 9.13 (76) | 0.005 | 1.1044 | 1.0403–1.1725 |

BP, blood pressure; CRP, C reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HC, hydrocortisone.

*Fisher's exact test.

Median follow‐up duration was 7 months (range 11 days to 16 years). Two year follow‐up was available for 28 patients. Four patients without previous visual symptoms had visual loss (unilateral permanent visual loss in two and unilateral temporary visual loss in two). Visual loss occurred, on average, 24 months after initial presentation. All four patients were on a tapering dose of oral prednisone at that time (on average 14 mg daily).

Discussion

Continuous visual symptoms despite steroid therapy were seen in 23% of patients, and 16% suffered visual deterioration during therapy. Risk factors for visual loss on presentation were disc swelling and hypertension. Risk factors for progressive visual loss included older age, elevated CRP and disc swelling.

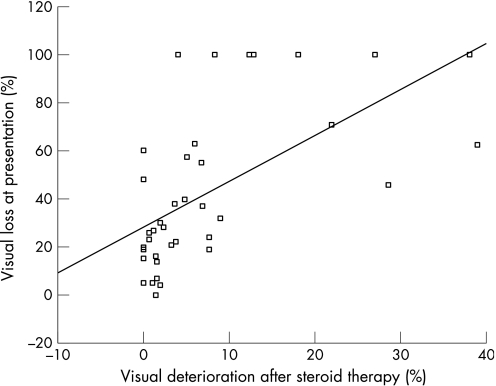

Fifty‐eight patients (3.1%) with visual loss after initiation of corticosteroid therapy were found among 1296 patients with TA in the literature (table 6) ranging from 0%3 to 38.9% in prospective series.4 In a meta‐analysis of 39 retrospective4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24 and prospective studies (table 6), we found a highly significant correlation (Pearson's correlation coefficient 0.604; p<0.0001) between the percentage of patients with visual loss on presentation and visual loss under corticosteroid therapy (fig 1). Visual loss on presentation may therefore predict visual deterioration under corticosteroid therapy, as also seen in our patients.

Table 6 Visual loss during corticosteroid therapy (prospective studies).

| Author | Year | Study design (cases) | n | Positive biopsy | Patients with visual loss (%) | Patients with ocular deterioration during therapy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birkhead33 | 1957 | Prospective | 55 | 55 (100%) | 21 (38%) | 2 (3.6%) |

| Palm34 | 1958 | Prospective | 31 | 13 (21%) | 31 (100%) | 4 (12.9%) |

| Parsons‐Smith35 | 1958 | Prospective | 50 (13 treated) | NR | 13/55; all 13 treated (24%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| Russell36 | 1959 | Retrospective (8) | 35 (21 treated) | 11 (31%) | 16/35 with visual symptoms (46%) | 6 (28.6%) |

| Prospective (27) | ||||||

| Mosher4 | 1959 | Retrospective | 32 (18 treated) | 23 (72%) | 20 with eye symptoms (62.5%) | 7 (38.9%) |

| Whitfield37 | 1963 | Prospective | 72 | NR | 40 (55%) | 1 (1.4%) |

| Cullen38 | 1967 | Prospective | 25 | 25 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 1 (4%) |

| Fauchald39 | 1972 | Prospective | 94 | 61 (65%) | 5 ocular symptoms (5%) | 1 (1.1%) |

| Hunder40 | 1975 | Prospective | 60 | 60 (100%) | 3 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Bengtsson41 | 1981 | Prospective | 27 | 17 (63%) | NR | 2 (7.4%) |

| Jones42 | 1981 | Prospective | 85 | 22 (26%) | 6/22 (27%) permanent | 1 (1.2%) |

| Behn3 | 1983 | Prospective | 68 | 25 (37%) | 10 (15%) | 0 (0%) |

| Boesen43 | 1987 | Prospective | 21 | 11 (52%) | NR | 0 (0%) |

| Caselli44 | 1988 | Prospective | 166 | 166 (100%) | 14 permanent (8.4%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| 17 transient | ||||||

| 8 scotoma | ||||||

| Kyle45 | 1989 | Prospective | 35 | NR | NR | 1 (2.9%) |

| Myles46 | 1992 | Prospective | 96 TA | 48/78 (61.5%) | NR | 4/96 (4%) |

| 210 PMR | NR | 3/210 PMR (1.4%) | ||||

| Aiello47 | 1993 | Prospective | 245 | 204 (83%) | 34 (14%) | 5 (1.6%) |

| Duhaut48 | 1999 | Prospective | 292 | 207 (71%) | 31 (55%) | 14 (6.8%) |

| Kupersmith49 | 1999 | Prospective | 22 | 19 (86%) | 7 (32%) | 2 (9%) |

| Chevalet50 | 2000 | Prospective | 164 | 128 (78%) | NR | 1 amaurosis (0.6%) |

| Kupersmith 2 | 2001 | Prospective | 20 | 20 (100%) | 4 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| Liozon29 | 2001 | Prospective | 174 | 147 (85%) | 48 (28%) visual symptoms; | 4 (2.3%) |

| 23 (13%) permanent | ||||||

| Danesh‐Meyer25 | 2005 | Prospective | 34 | 34 (100%) | 34 (100%) | (27% of eyes during the first 6 days) |

| SUM | 1838 | 1296 (70.5%) | 362 (19.7%) | 58 (3.1%) |

GC, Giant cells; NR, not reported; PMR, polymyalgia rheumatica; TA, temporal arteritis.

Figure 1 Visual deterioration in relationship to visual loss on presentation, in per cent, based on retrospective and prospective series with complete data from the literature.

Visual deterioration occurs in two peaks. The first peak manifests as progression of the ongoing flare on an unchanged steroid dose, typically during the first 6 days.25 The second peak occurs after weeks or months of tapering treatment. Relapses increase with reduction of corticosteroid therapy and were seen in 19% of patients within 1 year.26

Reasons for progression of visual loss despite treatment may include hypoperfusion of the optic disc, treatment delay, inadequate steroid dose, quick taper or hypercoagulability with retinal artery infarction, possibly due to steroid therapy. Continuation of arteritis despite adequate corticosteroid dose may be considered part of the spectrum of TA or may even be a separate disease entity.

Differential diagnoses mimicking TA include systemic lupus erythematodes, Sjögren's syndrome, rheumatoid arthritits, Behcet's disease, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, polyarteritis nodosa, Churg–Strauss syndrome, Wegener's granulomatosis and other rheumatic conditions presenting with granulomatous vasculitis such as Takyasu arteritis.27 Sarcoid, primary angiitis of the central nervous system, non‐arteritic AION, neoplastic conditions as well as viral infections (varicella zoster, human parvo virus B19, human herpes virus 6, herpes simplex) and nocardiosis should also be considered.

Risk factors for initial visual loss include transient visual ischaemic symptoms, increased platelet count, jaw claudication and HLA‐DRB1 phenotype.20,28 Constitutional symptoms and elevated liver enzymes are associated with a lower risk of visual loss.28,29 Risk factors for permanent visual loss include amaurosis fugax and cerebrovascular accidents.20

Risk factors for progressive visual loss may include occlusive strokes, possibly due to steroid therapy itself.30 Late recurrence of visual loss was associated with female sex, older age, worse initial visual acuity, oral (as compared to intravenous) initial steroid treatment and higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate.24 HLA DRB1 alleles were also associated with progressive symptoms.31

Intravenous or high dose oral corticosteroids remain the standard of care for patients at risk for visual loss.25 A retrospective review of 166 patients demonstrated better outcome in patients on low dose aspirin at the time of symptom onset.32 Aspirin may therefore decrease the rate of visual loss and strokes in patients with TA. Further research is on the way to determine effectiveness. Some authors also use heparin, in particular in patients with progressive visual loss.25 Additional steroid sparing agents during the long term treatment period have been tried but no positive randomised placebo controlled prospective trials are available.

Limitations of our study include the retrospective design and referral bias at a tertiary treatment centre. Our literature review attempted to compensate for these variations by comparing our data with previous studies in different settings.

The 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Criteria for the Classification of Giant Cell (Temporal) Arteritis1 were not applied to all 341 patients seen in our clinic because of the retrospective study design. We limited our study population to the gold standard of diagnosis prior to establishment of these criteria, a positive temporal artery biopsy. Nevertheless, all included patients met the 1990 ACR criteria. By making the positive biopsy a prerequisite, we likely applied more sensitive inclusion criteria. Stricter inclusion criteria may also have led to a selection bias towards more active cases. Our data are therefore valid for patients over 50 years old and in whom the biopsy is positive and at least one additional diagnostic ACR criterion is present. A prospective study on progressive visual loss according to ACR standards is needed.

Conclusion

Progression of visual loss despite steroid therapy occurs in a significant minority of patients with TA. In most patients, deterioration occurs within the first 3 days after initiation of steroid therapy. Individual risk anticipating treatment strategies might improve visual prognosis in TA.

Abbreviations

ACR - American College of Rheumatology

CRP - C reactive protein

TA - temporal arteritis

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Hunder G G, Bloch D A, Michel B A.et al The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 1990331122–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kupersmith M J, Speira R, Langer R.et al Visual function and quality of life among patients with giant cell (temporal) arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol 200121266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behn A R, Perera T, Myles A B. Polymyalgia rheumatica and corticosteroids: how much for how long? Ann Rheum Dis 198342374–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosher H A. Prognosis in temporal arteritis. Arch Ophthalmol 195962641–644. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meadows S P. Temporal arteritis and loss of vision. Trans Ophthal Soc UK 19547413–24. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meadows S P. Temporal or giant cell arteritis. Proc R Soc Med 196659329–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healey L A, Wilske K R. Manifestations of giant cell arteritis. Med Clin North Am 197760261–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorensen P S, Lorenzen I. Giant‐cell arteritis, temporal arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. Acta Med Scand 1977201207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huston K A, Hunder G G, Lie J T.et al Temporal arteritis. A 25‐year epidemiologic, clinical and pathologic study. Ann Int Med 197888162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calamia R J, Hunder G G. Clinical manifestations of giant cell (temporal) arteritis. Clin Rheum Dis 19806403 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez‐Herlihy L. Duration of corticosteroid therapy in giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol 19807361–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham E, Holland A, Avery A.et al Prognosis in giant‐cell arteritis. Br Med J 1981282269–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bengtsson B A. Eye complications in giant cell artertitis. Acta Med Scand 1982656S38–S43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delecoeuillerie G, Joly P, Cohen de Lara A.et al Polymyalgia rheumatica and temporal arteritis: a retrospective analysis of prognostic features and different corticosteroid regimens (11 year survey of 210 patients). Ann Rheum Dis 198847733–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chmelewski W L, McKnight K M, Agudelo C A.et al Presenting features and outcomes in patients undergoing temporal artery biopsy. Arch Intern Med 19921521690–1695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu G T, Glaser J S, Schatz N J.et al Visual morbidity in giant cell arteritis. Ophthalmology 19941011779–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meli B, Landau K, Gloor B P. The bane of giant cell arteritis from an ophthalmological viewpoint. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 19961261821–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Font C, Cid M C, Coll‐Vincent B.et al Clinical features in patients with permanent loss due to biopsy‐proven giant cell arteritis. Br J Rheumatol 199736251–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bahlas S, Ramus‐Remus C, Davis C. Clinical outcome of 149 patients with polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol 19982599–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez‐Gay M A, Garcia‐Porrua C, Llorca J.et al Visual manifestations of giant cell arteritis. Trends and clinical spectrum in 161 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 200079283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wenkel H. Bilateral amaurosis in 11 patients with giant cell arteritis confirmed by arterial biopsy. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 2001218658–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan C C, Paine M, O'Day J. Steroid management in giant cell arteritis. Br J Ophthalmol 2001851061–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayreh S S, Zimmerman B. Management of giant cell arteritis. Our 27‐year clinical study: new light on old controversies. Ophthalmologica 2003217239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan C C, Paine M, O'Day J. Predictors of recurrent ischemic optic neuropathy in giant cell arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol 20052514–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danesh‐Meyer H, Savino P J, Gamble G G. Poor prognosis of visual outcome after visual loss from giant cell arteritis. Ophthalmology 20051121098–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffman G S, Cid M C, Hellmann D B.et al A multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of adjuvant methotrexate treatment for giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002461309–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilke W S. Large vessel vasculitis (giant cell arteritis, Takayasu arteritis). Baillieres Clin Rheumatol 199711285–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez‐Gay M A, Blanco R, Rodriguez‐Valverde V.et al Permanent visual loss and cerebrovascular accidents in giant cell arteritis: predictors and response to treatment. Arthritis Rheum 1998411497–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liozon E, Herrmann F, Ly K.et al Risk factors for visual loss in giant cell (temporal) arteritis: a prospective study of 174 patients. Am J Med 2001111211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Staunton H, Stafford F, Leader M.et al Deterioration of giant cell arteritis with corticosteroid therapy. Arch Neurol 200057581–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rauzy O, Fort M, Nourashemi F.et al Relation between HLA DRB1 alleles and corticosteroid resistance in giant cell arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis 199857380–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nesher G, Berkun Y, Mates M.et al Low‐dose aspirin and prevention of cranial ischemic complications in giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004501332–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birkhead N C, Wagener H P, Shick R M. Treatment of temporal arteritis syndrome with adrenal corticosteroids. JAMA 1957163821–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palm E. The ocular crisis of the temporal arteritis syndrome (Horton). Acta Ophthalmol 195836208–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parson‐Smith G. Sudden blindness in cranial arteritis. Br J Ophthalmol 195943204–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell R W R. Giant cell arteritis. A review of 35 cases. Q J Med 1959112471–489. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitfield A G W, Bateman M, Cooke W T. Temporal arteritis. Br J Ophthalmol 196347555–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cullen J F. Ischaemic optic neuropathy. Trans Ophthal Soc UK 196787759–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fauchald P, Rygvold O, Oystese B. Temporal arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. Ann Intern Med 197277845–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunder G G, Sheps S G, Allen L A.et al Daily and alternate‐day corticosteroid regimens in treatment of giant cell arteritis. Ann Intern Med 197582613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bengtsson B A, Malmvall B E. The epidemiology of giant cell arteritis including temporal arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. Incidences of different clinical presentations and eye complications. Arthritis Rheum 198124899–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones J G, Hazleman B L. Prognosis and management of polymyalgia rheumatica. Ann Rheum Dis 1981401–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boesen P, Sorensen S F. Giant cell arteritis, temporal arteritis, and polymyalgia rheumatica in a Danish county. Arthritis Rheum 198730295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caselli R J, Hunder G G, Whisnant J P. Neurologic disease in biopsy‐proven giant cell (temporal) arteritis. Neurology 198838352–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kyle V, Hazleman B L. Treatment of polymyalgia and giant cell arteritis. I. Steroid regimens for the first two months. Ann Rheum Dis 198948658–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Myles A B, Perera T, Ridley M G. Treatment of blindness in giant cell arteritis by corticosteroid treatment. Br J Rheumatol 199231103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aiello P D, Trautmann J C, McPhee J T.et al Visual prognosis in giant cell arteritis. Ophthalmology 1993100550–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duhaut P, Pinede L, Bornet H.et al Biopsy proven and biopsy negative temporal arteritis: differences in clinical spectrum at the onset of the disease. Groupe de Recherche sur l'Arterite a Cellules Geantes. Ann Rheum Dis 199958335–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kupersmith M J, Langer R, Mitnick H.et al Visual performance in giant cell arteritis (temporal arteritis) after 1 year of therapy. Br J Ophthalmol 199983796–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chevalet P, Barrier J H, Pottier P.et al A randomized, multicenter controlled trial using intravenous pulses of methylprednisolone in the initial treatment of simple forms of giant cell arteritis: a one year followup study of 164 patients. J Rheumatol 2000271484–1491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]