Chorea can result from many causes, and the diagnostic workup can be challenging. Although often accompanied by other extrapyramidal symptoms, hydrocephalus has not been mentioned as a possible cause of chorea to date. Here we report an unusual case of chorea secondary to normal pressure hydrocephalus, which clearly improved after shunt placement. Hydrocephalus may cause extrapyramidal symptoms, which are most likely a result of pressure on tracts of the nigrostriatal pathway or the cortico‐striato‐pallido‐thalamo‐cortical circuit. Apparently, hydrocephalus induced pressure may occasionally also compromise the caudate nucleus which lies immediately adjacent to the enlarged ventricles, resulting in chorea. We suggest that clinicians should be more alert to hydrocephalus as a rare but reversible cause of chorea.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) typically presents with the triad of cognitive deterioration, abnormal gait and urinary incontinence. Additional akinetic or tremulous movements may result from both idiopathic and secondary NPH. In contrast, hyperkinetic movements other than tremor have not been reported to result from hydrocephalus. When present, such hyperkinetic movements in NPH were exclusively observed secondary to causes not related to the hydrocephalus.1 Indeed, secondary chorea has been described to result from a variety of causes, but not from hydrocephalus.2

Here we report a case of NPH induced chorea, which completely resolved after shunt placement. We will briefly discuss the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying movement disorders in hydrocephalus.

Case report

A 76‐year‐old woman presented with urinary incontinence and gradually increasing cognitive impairment, particularly a disturbed short term memory and spatiotemporal orientation. She later developed abundant involuntary movements of all extremities, which after 4 weeks eventually resulted in loss of ambulation. Her medical history revealed rheumatoid arthritis and mild cognitive impairment as a result of a small ischaemic stroke in the right cerebellum 1 year earlier, after which she had recovered to independent functioning and had been able to drive a car. She had not used dopaminergic medication, neuroleptics, antiemetics or any other drug known to induce chorea.2 Her family history was negative for Huntington's disease and other choreas.

Neurological examination showed marked cognitive impairment, notably impaired visuospatial orientation, attention and working memory. There were clear choreatic movements of her head and all extremities, which markedly interfered with walking. Balance was also disturbed. The presence of a possible concomitant cerebellar ataxia could not be ascertained because of prominent bradykinesia. Systemic signs of autoimmune disease were absent; erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 42 mm, which is consistent with her history of rheumatoid arthritis.

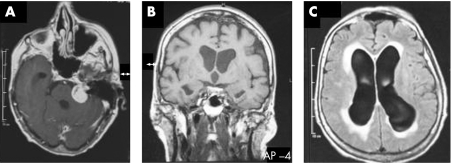

A cerebral MRI scan demonstrated a tumour in the left cerebellopontine angle, compatible with a vestibular schwannoma, which was accompanied by enlargement of the lateral ventricles and a patent aqueduct (fig 1). The tumour was otherwise without symptoms. The right cerebellum showed signs of ischaemic stroke from an earlier occurrence. There was mild atrophy of the caudate nucleus, but no signs of lacunar stroke in the basal ganglia or subthalamic nucleus.

Figure 1 (A) T1 weighted MRI scan demonstrated a tumour in the left cerebellopontine angle, compatible with a vestibular schwannoma which was accompanied by enlargement of the ventricles adjacent to the caudate nucleus. The aqueduct is patent (B). Fluid attenuated inversion recovery series showed periventricular effusion (C).

A ventriculo‐peritoneal drain with a medium pressure valve was placed, and CSF pressure was normal (18 cm H2O). Ventricular CSF showed increased protein (1.8 g/l). Glucose, cell count and cytological examination were normal. As the vestibular schwannoma was not symptomatic, no further treatment was initiated. Within weeks after the ventriculo‐peritoneal drain placement, cognitive function improved to premorbid levels with normal short term memory and spatio‐temporal orientation. The choreatic movements disappeared completely. A repeat MRI showed improvement of the hydrocephalus. The patient was able to live independently again. Three year radiological follow‐up revealed no increase in the vestibular schwannoma, and 5 year clinical follow‐up disclosed no recurrent chorea.

Discussion

We have presented a patient with chorea that was most likely secondary to idiopathic NPH. A causal relationship between chorea and hydrocephalus was suggested by various factors. Firstly, the chorea resolved completely shortly after shunt placement. Secondly, there was no recurrence of the chorea over time, with a maximal follow‐up of 5 years. Thirdly, other main causes of secondary chorea in elderly people were excluded, such as lacunar stroke in the basal ganglia or subthalamic nucleus and use of medications which are known to cause chorea. There were no systemic signs of autoimmune disorders at presentation or during follow‐up, and the mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (42 mm) was consistent with a prior history of rheumatic arthritis. This disease course—with an isolated “bout” of chorea that remitted shortly after shunting of NPH and that never recurred—is difficult to reconcile with a second concurrent disease, certainly when this was an autoimmune disease that was left untreated. We considered Sydenham's chorea as this may resolve spontaneously without treatment, but this disorder usually presents at 5–20 years of age. Rare episodes of Sydenham's chorea at older ages have been described, but such patients typically had several childhood episodes of Sydenham's chorea.3 We also considered Huntington's disease, but this was deemed unlikely because of the disease course, with complete remission shortly after shunting and the negative family history. Furthermore, the patient died 5 years later after a myocardial infarction without any signs of recurrent chorea.

Hydrocephalus induced movement disorders typically include tremor, rigidity, loss of postural reflexes, bradykinesia, a higher level “frontal” gait disorder and bradyphrenia.1 Signs of midbrain dysfunction, including Parinaud syndrome, may be present in cases of aqueduct stenosis. Hyperkinetic movement disorders have been described in hydrocephalus, but these were exclusively secondary to causes unrelated to hydrocephalus itself, such as the use of phenytoin or basal ganglia infarction. Huntington's disease has been associated with NPH in three cases, and with obstructive hydrocephalus in one case.4,5 These four patients had a positive family history of involuntary movements. Clinical improvement occurred after shunting in all patients, but the choreatic movements never disappeared fully, as was the case in our patient. Hydrocephalus might have disclosed a subclinical disposition of Huntington's chorea in these cases.

Hydrocephalus causes extrapyramidal symptoms, most likely due to local pressure on tracts of the nigrostriatal pathway or the cortico‐striato‐pallido‐thalamo‐cortical circuit. Parts of these pathways lie in close proximity to the ventricular system and may be subjected to volume effects or ischaemic changes secondary to ventriculomegaly, resulting in a hypokinetic rigid syndrome or tremor. Apparently, hydrocephalus induced pressure may occasionally also compromise the caudate nucleus which lies immediately adjacent to the enlarged ventricles, in this case resulting in chorea. Perhaps some of the cognitive impairment in this patient also resulted from caudate function.

Why such focal caudate nucleus involvement is not seen more frequently in hydrocephalus remains unclear. Perhaps chorea is under recognised as a sign of hydrocephalus (eg, because more severe bradykinesia distracts the clinician's attention from the more subtle signs of chorea). We suggest that clinicians should be more alert to hydrocephalus as a rare but reversible aetiology in chorea.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Krauss J K, Regel J P, Droste D W.et al Movement disorders in adult hydrocephalus. Mov Disord 1997153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardoso F, Seppi K, Mair K J.et al Seminar on choreas. Lancet Neurol 20065589–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison N A, Church A, Nisbet A.et al Late recurrences of Sydenham's chorea are not associated with anti‐basal ganglia antibodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004751478–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang B H, Lieberman A, Rovit R. Huntington's chorea associated with normal pressure hydrocephalus. Eur Neurol 197513189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorenzo N Y, Leibrock L G, Lorenzo A S. A single case of Huntington's disease simultaneously occurring with obstructive hydrocephalus. Surg Neurol 199135136–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]