Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is a hereditary small vessel disease caused by mutations of the Notch3 gene. Clinical manifestations include migraine with or without aura, psychiatric disorders, recurrent ischaemic strokes and cognitive decline. Brain MRI shows confluent hyperintense signal alterations involving characteristically the anterior part of the temporal lobes and widespread areas of the deep and periventricular white matter. Focal or generalised seizures represent a rare neurological manifestation in CADASIL with a frequency of 6–10% in two large series.1,2 Status epilepticus, however, has not been reported so far. Herein we describe a patient with CADASIL with an acute focal neurological deficit following a prolonged migraine attack. The symptoms were first interpreted as an ischaemic stroke but subsequently diagnosed to be due to a non‐convulsive status epilepticus.

Case report

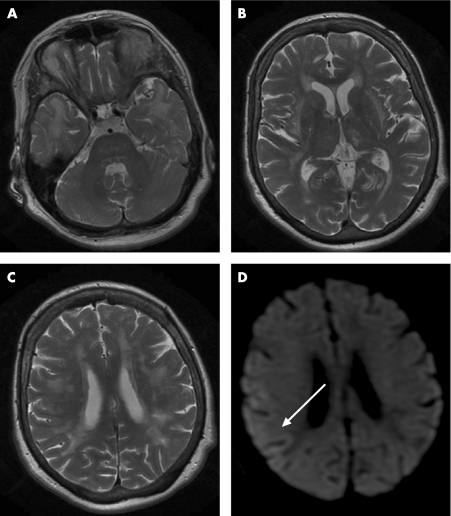

The 63‐year‐old right‐handed female had a history of severe and longlasting migraine attacks with visual aura since the age of 40 years. The patient's father died at age 63 years after a history of progressive behavioural changes interpreted as the result of recurrent strokes. At age 59 years, the patient underwent a neurological examination because of a 2 year history of depression and generalised anxiety. Neurological examination revealed unspecific mild subcortical neuropsychological deficits but was otherwise normal. Cerebral MRI showed confluent hyperintense signal abnormalities with prominent involvement of both temporal lobes, both thalami, external and extreme capsules, as well as widespread areas of the white matter (fig 1). The diagnosis of CADASIL was confirmed by detection of characteristic granular osmiophilic material in the skin biopsy and detection of an already described mutation in the Notch3 gene (C583T) (Professor E Tournier‐Lasserve, Hôpital Lariboisiere, Paris, France).3

Figure 1 T2 weighted MRI scans showing diffuse hyperintense signal abnormalities with prominent involvement of both temporal lobes (A), both thalami, external and extreme capsules (B), as well as widespread areas of the white matter (C). Diffusion weighted imaging does not show evidence of an acute ischaemic strokes but demonstrates a weak and diffuse signal alteration in the right parieto‐occipital cortex 24 h before the first EEG (arrow; D).

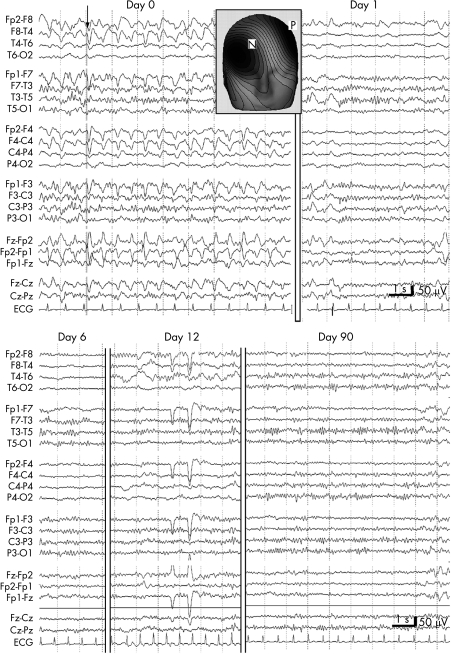

Between age 61 and 63 years, the patient had three episodes with sudden onset lasting for several hours up to 2 days with transient neurological symptoms, such as speech and gait disturbances, decreased responsiveness and recurrent vomiting. Because she was hospitalised in regional hospitals, no neurological examination or electroencephalography (EEG) were performed. Brain CT after the first episode demonstrated a new thalamic lesion suggesting an ischaemic origin of this particular episode, but the aetiology of the other episodes remained unclear. At age 63 years, she had migraine headaches without aura but recurrent vomiting lasting for 3 day. She was described as being confused, agitated, dysarthric and incoherent in her thoughts. At admission to our department, neurological examination revealed psychomotor slowing, confusion, neglect to the left and hemianopia to the left as well as right hemispheric neuropsychological deficits including visual ataxia and apraxia. An acute stroke was suspected. Diffusion weighted MRI (DWI), however, did not show any acute ischaemic lesion but revealed a weak, diffuse hyperintensity of the right parieto‐occipital cortex (fig 1). EEG recordings disclosed widespread right hemispheric attenuation and periodic frontally accentuated focal epileptic discharges consistent with the diagnosis of a non‐convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) (fig 2). Antiepileptic treatment with phenytoin 300 mg daily was initiated and led to prompt and persistent clinical and electroencephalographic recovery (fig 2).

Figure 2 EEG during non‐convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) (day 0 = 24 h after diffusion weighted MRI) demonstrates periodic right frontal 1.5/s epileptic discharges with right frontal predominance. The insert shows the voltage map of the sharp waves marked by the arrow (N, negative, P, positive). Intravenous midazolam controlled the NCSE (day 1), and subsequent treatment with phenytoin 300 mg daily led to cessation of the NCSE seizure activity but persisting right hemispheric attenuation which normalised later on (day 90).

Discussion

The epileptic origin of focal neurological deficits in this patient with CADASIL is suggested by the EEG findings, a DWI pattern consistent with a NCSE without evidence of acute ischaemic lesions and the good response to antiepileptic therapy. The DWI alterations, in addition, argue against the hypothesis of a persistent migraine aura.

The incidence of epileptic seizures in CADASIL is estimated to range between 6 and 10%. Nine of 10 patients with CADASIL with epileptic seizures in one study had generalised tonic–clonic seizures, and only one had focal seizures.2 In another study, all three CADASIL patients had generalised seizures.1 The incidence of seizures in patients with CADASIL seems to be lower compared with first time seizures in common stroke, affecting 12–15% of patients. In contrast, status epilepticus has been reported to occur in 14–19% of all patients with post‐stroke epileptic seizures.4 On the other hand, almost 10% of patients with CADASIL in a British survey developed a reversible acute encephalopathy with headache at onset, confusional state, fever, epileptic attacks and coma, similar to the clinical presentation of patients with familiar hemiplegic migraine.3 However, EEG in these patients revealed no epileptiform discharges.

The aetiology of epileptic seizures and reversible coma in CADASIL is still a matter of debate. A post‐stroke aetiology origin has been postulated, as in nine of 10 patients of one series, epileptic seizures occurred after stroke onset.2 In the absence of acute ischaemic lesions in the brain MRI, it remains hypothetical whether a transient ischaemic attack may have triggered an epileptic seizure or status epilepticus. In analogy to reversible coma and epilepsy in calcium channel disorders, epileptogenic changes in CADASIL could be primarily related to altered properties of the Notch3 signalling system. On the other hand, the association of migraine, reversible cognitive alterations and epileptic seizures ressembles the clinical pattern found in mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke‐like episodes (MELAS). A few reports suggest that Notch3 mutations in CADASIL might predispose to mitochondrial abnormalities. This hypothesis is based on the observation of an increased sequence variation of mitochondrial DNA in CADASIL pedigrees compared with healthy controls, and of muscle mitochondrial abnormalities in several CADASIL patients.5

In conclusion, our report demonstrates that a NCSE may mimic an ischaemic stroke or a prolonged migraine aura in patients with CADASIL. We propose that EEG should be performed in CADASIL patients with acute neurological deficits, particularly when no acute ischaemic alterations are found in DWI. In addition, evaluation of anticonvulsants as possible prophylactic treatment is warranted in a larger series of CADASIL patients.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Chabriat H, Vahedi K, Iba‐Zizen M T.et al Clinical spectrum of CADASIL: a study of 7 families. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Lancet 1995346934–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dichgans M, Mayer M, Uttner I.et al The phenotypic spectrum of CADASIL: clinical findings in 102 cases. Ann Neurol 199844731–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schon F, Martin R J, Prevett M.et al “CADASIL coma”: an underdiagnosed acute encephalopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 200374249–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rumbach L, Sablot D, Berger E.et al Status epilepticus in stroke: report on a hospital‐based stroke cohort. Neurology 200054350–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Annunen‐Rasila J, Finnila S, Mykkanen K.et al Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation and mutation rate in patients with CADASIL. Neurogenetics 20067185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]