Abstract

Background

Prescribed drugs in patients with Alzheimer's disease may affect the symptomatic progression of their disease, both positively and negatively.

Aim

To examine the effects of drugs on the progression of disease in a representative group of patients with Alzheimer's disease.

Methods

Patients with the diagnosis of probable Alzheimer's disease were recruited from the community. The prescribed drugs taken by 224 patients (mean age 82.3 years) were recorded at initial assessment and then correlated in logistic regression analysis with progression of the disease, defined as an increase of one point or more in the Global Deterioration Scale over the next 12‐month period.

Results

Patients who were taking antipsychotic drugs and sedatives had a significantly higher risk of deterioration than those who were taking none (odds ratios (ORs) 2.74 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.17 to 6.41) and 2.77 (95% CI 1.14 to 6.73), respectively). Higher risk of deterioration was observed in those who were taking both antipsychotic and sedative drugs together (OR 3.86 (95% CI 1.28 to 11.7). Patients taking drugs licensed for dementia, drugs affecting the renin–angiotensin system and statins had a significantly lower risk of deterioration than those who were not taking any of these drugs (ORs 0.49 (95% CI 0.25 to 0.97), 0.31 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.85) and 0.12 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.52), respectively).

Conclusion

Our findings have implications for both clinicians and trialists. Most importantly, clinicians should carefully weigh any potential benefits of antipsychotics and benzodiazepines, especially in combination, against the risk of increased decline. Researchers need to be aware of the potential of not only licensed drugs for dementia but also drugs affecting the renin–angiotensin system and statins in reducing progression in clinical trials.

Alzheimer's disease is a degenerative disorder of the brain that begins insidiously and progresses gradually over time. The duration of the disease varies, with an average of 8.5 years from onset of the disease to death although this average figure disguises considerable individual differences. Understanding these differences is critical; obviously so for patients and their carers, and also increasingly for researchers. This is especially true for trials of potential disease‐modifying agents in Alzheimer's disease. For these long‐term trials of decline, comparisons between treated and placebo groups is dependent on the slope of decline being sufficiently steep over the trial period to measure a difference and on the slope of decline in the two groups being similar before treatment. Understanding the variables that influence decline is therefore of vital importance. Previously, older age,1 low cognitive1 and functional2 performance, presence of psychotic symptoms,3,4,5,6 extrapyramidal signs3,4 and agitation3 have all been linked with faster decline of the disease.

Prescribed drugs also affect the symptomatic progression of Alzheimer's disease, both positively and negatively. Drugs prescribed for patients with Alzheimer's disease can be broadly classified in three categories: drugs for dementia, which aim to enhance cognitive function and delay progression of symptoms of the disease, at least in the short term; drugs acting on the central nervous system, such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, hypnotics and anxiolytics, which aim to ameliorate neuropsychiatric symptoms; and drugs prescribed for other medical conditions that are common in this age group.

Studies investigating the association of drugs with progression of Alzheimer's disease have done so mostly by examining either individual drugs (eg, imipramine), drugs belonging to the same category (eg, statins) or a family of drugs (eg, neurotropics). We set out to build on these previous studies by examining the effects of all prescribed drugs on the progression of disease in a group of patients with Alzheimer's disease.

Methods

Study population

As part of an ongoing cohort study, we recruited white Europeans aged ⩾65 years in south London and Guildford, mostly from community mental health teams for elderly people and from nursing homes in the areas covered by these teams. The remainder were recruited through primary care, and all patients were community dwellers at the time of assessment. We aimed to recruit a representative sample known to these teams with Alzheimer's disease, regardless of disease severity. The diagnosis of probable Alzheimer's disease was made according to NINCDS‐ADRDA criteria7 using operationalised criteria from information gained from uniform semistructured and structured clinical evaluation, as described previously.8 All patients were reviewed by a consultant psychiatrist, and in cases of equivocal or uncertain diagnosis the opinion of a second consultant psychiatrist was sought. Patients were then followed up annually. Patients who died during the first 12 months, and thus before the first follow‐up appointment, were not included in the study.

Drugs

Drugs were recorded at baseline individually, including the dosage and duration of treatment. Patients or their carers were asked to show the drugs that they were actually taking. For the purpose of this study, drugs were classified according to the pharmacological properties as stated in the British National Formulary and are listed in table 1. Antipsychotic drugs were grouped as older and atypical antipsychotics and antidepressants drugs as tricyclic, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and lithium‐containing compounds. In the group of hypnotics and anxiolytics were benzodiazepines (BZD) and BZD‐related drugs. The three acetylcholinesterase‐inhibiting drugs (donezepil, rivastigmine and galantamine) and the N‐methyl‐d‐aspartate (NMDA)‐receptor antagonist (memantine) were grouped together in the category of drugs for dementia. Multivitamin compounds were considered only if they contained vitamins E, B12 or folic acid. In the category of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin in small doses (⩽325 mg/day), which is given for its antiplatelet properties, was kept separate from other NSAIDs or larger doses of aspirin. The antihypertensive and heart‐related drugs included a heterogeneous group of drugs, but drugs with antihypertensive properties were kept distinct. In the class of drugs affecting the renin–angiotensin system, the angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors were grouped as brain (ie, captopril and perindopril) and non‐brain‐penetrant drugs (ie, enalapril, lisinopril and ramipril).9 Statins were the only lipid‐regulating drugs administered to the patients in this study. In the category of drugs with potential antimuscarinic effect, we grouped sedating and non‐sedating antihistamines, antimuscarinic drugs used in Parkinson's disease and drugs with antimuscarinic effect used for urinary incontinence. We also recorded inhaled/nasal or oral corticosteroids, drugs for diabetes, thyroid hormone supplements, drugs with antiepileptic properties, the use of levodopa and, finally, the use of any type of laxative. Only one patient was taking hormone‐replacement therapy, and thus is not shown in table 1.

Table 1 Proportion of patients taking each type of drug stratified by age, sex and GDS at baseline.

| Patients n (%) | Mean (SD) age (years) | Women n (%) | Mean (SD) GDS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotic drugs | ||||

| None | 190 (85) | 82.1 (6.5) | 135 (71) | 4.77 (0.92)* |

| Older antipsychotics | 7 (3) | 83.6 (7.8) | 7 (100) | 5.57 (0.79) |

| Atypical antipsychotics | 27 (12) | 82.9 (6.3) | 22 (82) | 5.26 (0.76) |

| Antidepressant drugs | ||||

| None | 170 (76) | 82.8 (6.2) | 119 (70) | 4.80 (0.90)* |

| Tricyclic drugs | 7 (3) | 84.8 (7.8) | 5 (71) | 5.71 (0.49) |

| SSRIs/tricyclic‐related drugs | 46 (21) | 80.1 (7.0) | 40 (87) | 4.89 (0.97) |

| Lithium | 1 (0.4) | 79 (—) | 0 | 6.00 (—) |

| Hypnotics and anxiolytics | ||||

| None | 194 (87) | 82.2 (6.7) | 140 (72) | 4.77 (0.92)* |

| BZD/BZD‐related drugs | 30 (13) | 82.4 (5.2) | 24 (80) | 5.40 (0.68) |

| Drugs for dementia | ||||

| None | 137 (61) | 84.2 (5.8)* | 115 (84)* | 5.10 (0.87)* |

| Achs/NMDA antagonists | 86 (38) | 79.3 (6.3) | 48 (56) | 4.47 (0.86) |

| Achs and Ginkgo biloba | 1 (0.4) | 73 (—) | 1 (100) | 4.00 (—) |

| Vitamins/antioxidants | ||||

| None | 203 (91) | 82.1 (6.5) | 146 (74) | 4.84 (0.93) |

| Vitamin E | 1 (0.4) | 73 (—) | 0 | 5.00 (—) |

| Vitamin B12 or folic acid | 20 (9) | 84.3 (6.5) | 18 (90) | 4.95 (0.83) |

| NSAIDs | ||||

| None | 155 (69) | 82.3 (6.5) | 116 (75) | 4.92 (0.92) |

| Small doses of aspirin (<325 mg/day) | 53 (24) | 82.1 (6.9) | 35 (66) | 4.64 (0.88) |

| NSAIDs | 16 (7) | 82.3 (5.0) | 13 (81) | 4.94 (1.00) |

| Antihypertensive and heart‐related drugs | ||||

| None | 132 (59) | 81.5 (7.0)* | 97 (74) | 4.78 (0.98) |

| Any | 92 (41) | 83.3 (5.5) | 67 (73) | 4.96 (0.81) |

| Drugs affecting the renin–angiotensin system | ||||

| None | 202 (90) | 82.3 (6.6) | 148 (73) | 4.85 (0.92) |

| ACE inhibitors | 20 (9) | 82.9 (5.3) | 15 (75) | 4.85 (0.99) |

| Angiotensin‐II receptor antagonists | 2 (1) | 76.5 (0.7) | 1 (50) | 5.00 (0.00) |

| Lipid‐regulating drugs | ||||

| None | 212 (95) | 82.4 (6.4) | 155 (73) | 4.87 (0.91) |

| Statins | 12 (5) | 79.5 (7.5) | 9 (75) | 4.50 (1.09) |

| Drugs with antimuscarinic effect | ||||

| None | 215 (96) | 82.4 (6.4) | 162 (75)* | 4.86 (0.91) |

| Any | 9 (4) | 79.6 (8.7) | 2 (22) | 4.67 (1.12) |

| Corticosteroids | ||||

| None | 211 (94) | 82.2 (6.6) | 153 (73) | 4.83 (0.93) |

| Inhaled or nasal application | 9 (4) | 84.2 (4.3) | 7 (78) | 5.22 (0.44) |

| Oral intake | 4 (2) | 81.3 (5.6) | 4 (100) | 5.25 (0.96) |

| Drugs for diabetes | ||||

| None | 214 (96) | 82.4 (6.5) | 158 (74) | 4.86 (0.92) |

| Oral drugs for diabetes or insulin | 10 (4) | 79.5 (7.0) | 6 (60) | 4.70 (0.82) |

| Thyroid hormones | ||||

| None | 203 (91) | 82.3 (6.4) | 146 (72) | 4.86 (0.92) |

| Any | 21 (9) | 81.9 (7.4) | 18 (86) | 4.81 (0.93) |

| Antiparkinsonian drugs | ||||

| None | 222 (99) | 82.3 (6.5) | 164 (74) | 4.85 (0.92) |

| Levodopa | 2 (1) | 75 (7.1) | 0 | 5.00 (1.41) |

| Antiepileptic drugs | ||||

| None | 220 (98) | 82.2 (6.5) | 161 (73) | 4.85 (0.92) |

| Any | 4 (2) | 84.8 (8.5) | 3 (75) | 5.00 (0.82) |

| Laxatives | ||||

| None | 198 (88) | 81.6 (6.4)* | 145 (73) | 4.79 (0.92) |

| Any | 26 (12) | 87.0 (4.7) | 19 (73) | 5.31 (0.79) |

ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; Achs, acetylcholinesterase‐inhibiting drugs; BZD, benzodiazepine; GDS, Global Deterioration Scale; NMDA, N‐methyl‐d‐aspartate; NSAID, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

*p<0.05.

Assessments and definition of rate of progression

Demographic details were recorded in all cases. Among other standardised scales, the Neuropsychiatry Inventory10 and Webster Scale11 were used to assess the presence of psychotic symptoms and extrapyramidal signs, respectively. Delusions, hallucinations and aggressive behaviour were considered present if they had occurred during a 12‐month period before recruitment. The Global Deterioration Scale (GDS)12 was administered to all patients at baseline and 12 months later by trained researchers. The GDS was used to assess the severity of the clinical characteristics of Alzheimer's disease that are associated with progression of the disease. The GDS is divided into seven identifiable stages (scores 1–7), which encompass the earliest to the most severe symptoms of the disease considering cognitive and functional impairment, as well as behaviour disturbances. Deterioration of the symptoms of the disease was defined as at least one stage/point increase in GDS between the initial and 12‐month assessments. On the basis of this definition, patients were then divided into those with slower (no change or decrease in GDS) and those with faster (increase in GDS) decline. Patients with a GDS score of 7 at baseline assessment were excluded from the analysis, as further deterioration cannot be detected at this stage.

Statistical methods

The Mann–Whitney U test for two samples was used in non‐parametric comparisons and the χ2 test with Yates‐corrected p value in the comparison of proportions. Patients with slower and faster declines were entered as the dependent dichotomous variable in a multivariate logistic regression analysis model investigating the relationship of patients taking different types of drugs, regardless of dose, compared with those who were not taking any. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed after adjusting for confounding factors such as age, sex and baseline severity of the disease (ie, baseline GDS). Subsequently, in addition to the above confounding factors, the presence of delusions, hallucinations, aggressive behaviour and extrapyramidal signs was entered into the model. Finally, drugs that were notably associated with decline were entered in a multivariate logistic regression model to adjust for possible confounding effects between drugs.

The study was approved by the relevant ethics committees.

Results

Sample characteristics

All 257 patients with Alzheimer's disease in the cohort (mean (standard deviation (SD)) age 82.2 (6.6) years, 76% women) were initially considered for this study. Of these, 33 were excluded because they had a GDS score of 7 at baseline. The clinical characteristics of the remaining 224 patients (mean (SD) age 82.3 (6.5) years, 73% women, mean (SD) years of education 10.3 (2.2)) were subsequently analysed. Over a 12‐month period from the initial assessment, 134 (60%) patients had a faster decline.

Table 1 shows the proportion of patients taking each type of drug stratified by age, sex and GDS at baseline. In all, 34 (15%) patients were taking antipsychotic drugs, 54 (24%) antidepressants and 30 (13%) BZD or BZD‐related drugs. Older antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants and hypnotics/anxiolytics were prescribed considerably more often in those with more severe stages of the disease.

The 87 (39%) patients who were taking drugs for dementia were younger, with a higher proportion of men and in milder stages of the disease compared with those who were not prescribed any drug. Only 1 (0.4%) patient was taking the antioxidant vitamin E, whereas 20 (9%) were taking vitamin B12 or folic acid.

Among the most commonly prescribed drugs for medical conditions other than Alzheimer's disease in this elderly population were antihypertensives and heart‐related drugs (41%), including drugs affecting the renin–angiotensin system, small doses of aspirin for the antiplatelet action (24%), laxatives (12%), thyroid supplements (9%), statins (5%) and drugs with potential antimuscarinic effects (4%). Of the nine patients who were taking drugs with potential antimuscarinic effect, eight (seven men and one woman) were taking them for urinary incontinence, and this explains the higher proportion of men in this group. Years of education in the univariate analysis did not differ significantly between patients who were taking each type of drug compared with those who were not taking any (data are not shown).

Association of the prescribed drugs with rate of progression

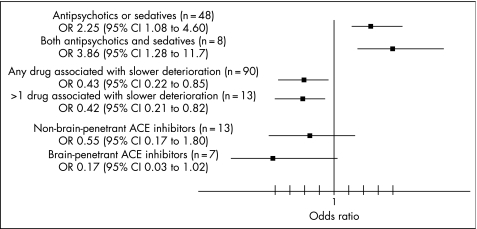

Patients with Alzheimer's disease who were taking antipsychotic drugs and those taking sedatives were more likely to have a faster rate of deterioration than those who were not taking any of these drugs (OR 2.74 (95% CI 1.17 to 6.41) and 2.77 (1.14 to 6.73), respectively; table 2). The older generation of the antipsychotic drugs tended to be more strongly associated with faster rate of deterioration than atypical antipsychotic drugs, although the difference between the two was not significant. Those patients who were taking either antipsychotics or sedatives had an increased risk of rapid deterioration compared with those who were taking none (OR 2.25 (95% CI 1.08 to 4.60), but an even higher risk of rapid deterioration was observed in those who were taking both antipsychotic and sedative drugs than those who were taking none (OR 3.86 (95% CI 1.28 to 11.7)) (fig 1).

Table 2 The association of drugs versus no drugs with the risk of deterioration in a logistic regression model adjusted for confounding factors.

| OR (95% CI)* | OR (95% CI)† | OR (95% CI)‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotic drugs | |||

| Older/atypical antipsychotics | 2.74 (1.17 to 6.41) | 2.72 (1.13 to 6.52) | 2.70 (1.11 to 6.6) |

| Older antipsychotics | 8.35 (0.93 to 75.08) | ||

| Atypical antipsychotics | 1.48 (0.94 to 2.32) | ||

| Antidepressant drugs | |||

| Any antidepressant drug | 0.96 (0.68 to 1.35) | ||

| Tricyclic antidepressant | 0.94 (0.19 to 4.57) | ||

| SSRIs | 1.01 (0.71 to 1.46) | ||

| Hypnotics and anxiolytics | |||

| BZD/BZD‐related drugs | 2.77 (1.14 to 6.73) | 2.90 (1.17 to 7.20) | 2.62 (1.04 to 6.6) |

| Drugs for dementia | |||

| Achs/NMDA antagonists | 0.49 (0.25 to 0.97) | 0.50 (0.25 to 1.01) | 0.47 (0.23 to 0.97) |

| Vitamins/antioxidants | |||

| Vitamins E/B12/folic acid | 0.72 (0.28 to 1.84) | ||

| NSAIDs | |||

| Small doses of aspirin (⩽325 mg/day) | 1.07 (0.54 to 2.12) | ||

| NSAIDs | 1.00 (0.57 to 1.76) | ||

| Antihypertensive and heart‐related drugs | |||

| Antihypertensive/any heart‐related drug | 1.04 (0.54 to 1.84) | ||

| Any antihypertensive drug | 0.74 (0.39 to 1.40) | ||

| Drugs affecting the renin—angiotensin system | |||

| ACE inhibitors/A‐II receptor antagonists | 0.31 (0.12 to 0.83) | 0.31 (0.11 to 0.85) | 0.38 (0.13 to 1.12) |

| ACE inhibitors | 0.37 (0.14 to 0.99) | ||

| Lipid‐regulating drugs | |||

| Statins | 0.12 (0.03 to 0.52) | 0.09 (0.02 to 0.41) | 0.17 (0.03 to 0.96) |

| Drugs with antimuscarinic effect | |||

| Any | 0.48 (0.11 to 2.11) | ||

| Corticosteroids | |||

| Inhaled/nasal | 0.66 (0.17 to 2.60) | ||

| Oral intake | 1.60 (0.49 to 5.20) | ||

| Drugs for diabetes | |||

| Oral drugs for diabetes or insulin | 0.76 (0.24 to 2.46) | ||

| Thyroid hormones | |||

| Any | 1.01 (0.39 to 2.66) | ||

| Antiepileptic drugs | |||

| Any | 2.40 (0.23 to 25.11) | ||

| Laxatives | |||

| Any | 2.22 (0.87 to 5.66) |

ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; Achs, acetylcholinesterase‐inhibiting drugs; BZD, benzodiazepine; NMDA, N‐methyl‐d‐aspartate; NSAIDs, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

*Odds ratio (OR) with 95% confident intervals (95% CI) adjusted for age, sex and Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) at baseline

†OR with (95% CI) adjusted in addition to the above for presence of delusions, hallucinations, aggression and extrapyramidal signs.

‡OR with (95% CI) adjusted for age, sex, baseline GDS, antipsychotic drugs, BZD/BZD‐related drugs, drugs for dementia, drugs affecting the renin–angiotensin system and statins.

Figure 1 Comparison of patients who were taking antipsychotics and sedatives, drugs associated with slower deterioration (drugs licensed for dementia, drugs affecting the renin–angiotensin system and statins) and brain‐penetrant and non‐penetrant angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors with those who were not taking any.

On the other hand, patients who were taking acetylcholinesterase inhibitors or NMDA antagonists, drugs affecting the renin–angiotensin system and statins had a significantly lower risk of rapid deterioration than those who did not take any of these drugs (ORs 0.49 (95% CI 0.25 to 0.97), 0.31 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.85) and 0.12 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.52), respectively). However, patients who were taking two or more of these type of drugs did not show an additive protective effect compared with those who were taking none of these (fig 1). This figure also shows that those who were taking brain‐penetrant ACE inhibitors tended to associate stronger with lower risk of rapid deterioration than those taking non‐brain‐penetrant ACE inhibitors.

The association reported so far of each prescribed drug with the speed of decline was adjusted in the multivariate logistic regression model for age, sex and GDS at baseline. GDS at baseline was used to account for cognitive and functional state. Additional adjustment with factors that were found in the literature to associate with faster decline of the disease, such as the presence of delusions, hallucinations, aggression and extrapyramidal signs, did not significantly change the associations, with the exception of the drugs licensed for dementia, which was borderline (p = 0.05; table 2).

To account for the interaction among drugs, all drugs that were found to correlate significantly with progression of the disease were entered in the multivariate logistic regression model (table 2). In all cases, the significant association between each drug with rate of decline of the disease was maintained, with the exception of the drugs affecting the renin–angiotensin system.

Discussion

Although many individual drugs and classes of drugs have previously been shown to alter risk of Alzheimer's disease and some have been shown to alter progression, to our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study of a large cohort of patients with Alzheimer's disease that measures the effects of all prescribed drugs on the rate of decline. We find surprisingly large effects of drug on progression, and discuss these by drug class below.

Antipsychotics, hypnotics/anxiolytics and antidepressants

We found an association between antipsychotic and anxiolytic or sedating drugs with faster decline that was additive, but did not find such an association with antidepressants. Antipsychotic and hypnotic/anxiolytic drugs are commonly prescribed to patients with Alzheimer's disease for the behaviour or mood disturbances common in this disorder.13 In this large, community‐based, representative sample, their use was associated with an increased risk of deterioration. The concurrent use of these drugs had an additive effect and was associated with an even higher risk of progression. The older generation of antipsychotic drugs tended to associate stronger with the rate of progression than atypical antipsychotic drugs, probably because of the small number of patients in each subcategory of these drugs, and this did not reach statistical significance. Antidepressants were also commonly prescribed, but were not associated with the course of the disease.

In our study, a larger proportion of patients were taking these drugs compared with some previous studies.5,14 This may be because we included patients with relatively advanced stages of the disease, and possibly also because of increased awareness and detection of depression in these patients recruited largely through community mental health teams for older adults. Antipsychotic drugs are used not only to treat psychosis but also a wider range of abnormal behaviour, including restlessness, agitation, aggression, insomnia, wandering or a combination of these.15,16 The presence of psychotic symptoms and extrapyramidal signs did not seem to have a confounding effect on the association between antipsychotic drugs and progression of the disease. However, they have been linked with increased rates of cognitive and functional decline,3,4,6,17 although in these earlier studies, it is at least possible that the apparent association between faster decline and psychosis was confounded by drugs prescribed for the psychosis. Faster decline associated with the use of antipsychotic drugs could be explained by worsening cognitive deficits through their anticholinergic effects, sedation or other common side effects, such as increased extrapyramidal symptoms or orthostatic hypotension. Atypical antipsychotics, which have fewer of these side effects, may be less associated with decline as Livingston et al18 showed in a longitudinal cohort of patients with Alzheimer's disease. In our study, in line with the findings of Livingston et al,18 atypical antipsychotics seemed to be less associated with the speed of decline of Alzheimer's disease.

BZD may induce memory disturbances in elderly people, not only in current19 but also in former users.20 BZDs have also been linked with increased risk of falls and death in elderly people without dementia,21,22 and with death, but not with cognitive or functional decline in patients with Alzheimer's disease.5 It has been suggested that the agonist action of the BZDs on γ‐aminobutyric acid receptors may explain their effect on cognition.23

Tricyclic antidepressants have prominent anticholinergic side effects, and thus might worsen memory, increase confusion and counteract the beneficial effect expected by acetylcholinesterase inhibitor drugs. We might have expected to see an effect of antidepressants on decline but did not do so, perhaps because of the small numbers of patients receiving these older drugs.

Antihypertensive drugs, statins and NSAIDs

We also found that both ACE inhibitors/angiotensin‐II receptor antagonists and statins were inversely associated with decline of the disease, whereas all antihypertensive drugs grouped together were not. The use of NSAIDs in our group of patients was also not associated with the rate of decline.

Hypertension has been linked with cognitive decline,24,25 and treatment of hypertension decreased the incidence of dementia, although it is debated whether it is mediated by lowering the blood pressure itself or by a class effect of the antihypertensive drugs.26 ACE inhibitors, in particular, seem to delay the decline of cognitive impairment in individuals with mild cognitive impairment,27 and might also have a similar effect in patients with Alzheimer's disease.28 Our finding of slower decline in relation to ACE inhibitors and statins was possibly owing to the confounding effects of hypertension and vascular disease on dementia. However, this does not seem to be the most obvious explanation of our observation, as we found no effect of all antihypertensives together on decline—the finding seems rather specific to these two classes of compounds. Moreover, we observed a trend towards a difference between brain‐penetrant and non‐penetrant ACE inhibitors on decline in Alzheimer's disease in line with a direct effect of ACE inhibitors rather than an indirect effect via lowering the arterial blood pressure.28,29 Interestingly, we note an antiflammatory effect of brain‐penetrating ACE inhibitors9,30 and the association between variation in the gene encoding ACE and risk of Alzheimer's disease.31,32

Several biological and epidemiological studies have reported that high serum cholesterol levels could be a potential risk factor for Alzheimer's disease,33,34,35,36 and that lipid‐lowering agents including statins,37 as well as statin therapy alone,38,39,40 might delay or even prevent the pathogenesis and clinical manifestation of the disease. Hajjar et al41 in a case–control retrospective study showed that 23 patients with dementia on statin therapy had their Mini‐Mental State Examination scores improved compared with the control group.41 Further, 25 patients in a randomised control study, who were receiving atorvastatin 80 mg daily, had a significantly higher Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–cognitive subscale score at 6 months than the placebo group.42 At 12 months after randomisation, the trend remained, but it was not significant. The mechanism through which statins might exert their potential benefit is only putative. The lower levels of cholesterol, a systemic antiflammatory effect and an effect of endothelial nitric oxide synthase on the cerebral capillaries have been suggested.43,44,45

Although long‐term use of NSAIDs seemed to protect against the development of Alzheimer's disease,46 a potential protective role on the course of Alzheimer's disease has been controversial, with studies reporting no47 or small48,49 benefit. Our findings of no effect of NSAIDs on decline are in line with these second, and disappointing, studies.

Memory‐related drugs, vitamins and antioxidants

About one third of patients with Alzheimer's disease participating in our study were taking drugs for dementia and, in particular, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors or the NMDA antagonist memantine. The use of these drugs for dementia was associated with slower deterioration of the symptoms of the disease. These classes of drugs are now widely used in patients with Alzheimer's disease, as a consequence of the results of many clinical trials and meta‐analysis.50 Nonetheless, their use has also been criticised, the size of clinical benefit mainly being questioned.51 We find a significant effect of these compounds as a group, although, interestingly, not as large as an effect as with the statins or ACE inhibitors.

Conclusions

The focus of this study was on the effect of drugs prescribed to patients in different stages of Alzheimer's disease on rate of progression of the dementia, and, with the exception of the cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine, not on the condition for which these drugs were being prescribed. Further, the findings of this study do not prove causality. The dosage of the drugs prescribed was not considered, and some of their effects may be dose related. Compliance during the 12‐month period was also not considered, but any potential bias thus introduced would be to underestimate association with progression. To mitigate the effects of compliance or changes in prescriptions, we chose to look at the rate of deterioration of the disease over a 1‐year period. The definition of deterioration of the symptoms of the disease was based on the GDS, as a scale that encompasses different aspects of the disease (memory, function, behaviour), and therefore more closely matches decline as experienced by patients, carers and clinicians than a unimodal assessment such as cognition. The baseline GDS was used in the multivariate logistic analysis to adjust for the severity of the disease, as severity of the disease itself is a confounding factor not only for progression but also for prescribing habits. Deterioration may be non‐linear and this may be another confounding factor. Further, deterioration was defined as a dichotomous variable and this may reduce the power of the analysis. Future studies need to account for decline over longer periods of time.

Despite these caveats, we found considerable variation in rate of decline associated with various drugs. We found less decline in patients treated with drugs licensed for dementia, but this protective effect was lower than for other drugs, including statins and ACE inhibitors. We found greater decline in patients treated with antipsychotics and BZD, and the effects of these drugs are additive. These observations have important implications for both clinicians and trialists. Most importantly, clinicians should be aware that antipsychotics and BZD, especially in combination, may hasten decline. Prescribing these classes of drugs may be unavoidable at times, but any potential benefits must be carefully weighed against the risk of increased decline. It is reassuring that the drugs licensed for Alzheimer's disease do seem to slow decline over a year, but clinicians may be sobered by the observation that the effect size is smaller than that found for statins. Finally, trials in Alzheimer's disease are increasingly turning to a slope analysis comparing rate of decline in a putative disease‐modifying treatment with placebo. Our findings suggest that close attention should be paid to the classes of drugs in both arms of such a trial—at least over a year, differences between patients taking BZD on one hand and statins on the other, both drugs commonly prescribed to elderly people, are likely to be greater than even the most optimistic trialist's projections for their compound.

Abbreviations

ACE - angiotensin‐converting enzyme

BZD - benzodiazepines

GDS - Global Deterioration Scale

NMDA - N‐methyl‐d‐aspartate

NSAID - non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug

Footnotes

This study was part of cohort studies funded by the Alzheimer's Research Trust and the Medical Research Council.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Ruitenberg A, Kalmijn S, de Ridder M A.et al Prognosis of Alzheimer's disease: the Rotterdam Study. Neuroepidemiology 200120188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguero‐Torres H, Fratiglioni L, Guo Z.et al Prognostic factors in very old demented adults: a seven‐year follow‐up from a population‐based survey in Stockholm. J Am Geriatr Soc 199846444–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chui H C, Lyness S A, Sobel E.et al Extrapyramidal signs and psychiatric symptoms predict faster cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol 199451676–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stern Y, Albert M, Brandt J.et al Utility of extrapyramidal signs and psychosis as predictors of cognitive and functional decline, nursing home admission, and death in Alzheimer's disease: prospective analyses from the Predictors Study. Neurology 1994442300–2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez O L, Wisniewski S R, Becker J T.et al Psychiatric medication and abnormal behavior as predictors of progression in probable Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 1999561266–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scarmeas N, Brandt J, Albert M.et al Delusions and hallucinations are associated with worse outcome in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2005621601–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M.et al Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS‐ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology 198434939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Archer N, Brown R G, Boothby H.et al The NEO‐FFI is a reliable measure of premorbid personality in patients with probable Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 200621477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohrui T, Tomita N, Sato‐Nakagawa T.et al Effects of brain‐penetrating ACE inhibitors on Alzheimer disease progression. Neurology 2004631324–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings J L, Mega M, Gray K.et al The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994442308–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webster D D. Critical analysis of the disability in Parkinson's disease. Mod Treat 19685257–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reisberg B, Ferris S H, de Leon M J.et al The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry 19821391136–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bassiony M M, Steinberg M S, Warren A.et al Delusions and hallucinations in Alzheimer's disease: prevalence and clinical correlates. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 20001599–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendez M F, Martin R J, Smyth K A.et al Psychiatric symptoms associated with Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1990228–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Semla T P, Cohen D, Freels S.et al Psychotropic drug use in relation to psychiatric symptoms in community‐living persons with Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacotherapy 199515495–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devanand D P, Levy S R. Neuroleptic treatment of agitation and psychosis in dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 19958(Suppl 1)S18–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tran M, Bedard M, Molloy D W.et al Associations between psychotic symptoms and dependence in activities of daily living among older adults with Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr 200315171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livingston G, Walker A E, Katona C L.et al Antipsychotics and cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease: the LASER‐AD longitudinal study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006; doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.094342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Dealberto M J, McAvay G J, Seeman T.et al Psychotropic drug use and cognitive decline among older men and women. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 199712567–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barker M J, Greenwood K M, Jackson M.et al Persistence of cognitive effects after withdrawal from long‐term benzodiazepine use: a meta‐analysis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 200419437–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray W A. Psychotropic drugs and injuries among the elderly: a review. J Clin Psychopharmacol 199212386–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wysowski D K, Baum C, Ferguson W J.et al Sedative‐hypnotic drugs and the risk of hip fracture. J Clin Epidemiol 199649111–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lagnaoui R, Begaud B, Moore N.et al Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: a nested case‐control study. J Clin Epidemiol 200255314–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilander L, Nyman H, Boberg M.et al Hypertension is related to cognitive impairment: a 20‐year follow‐up of 999 men. Hypertension 199831780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knopman D, Boland L L, Mosley T.et al Cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline in middle‐aged adults. Neurology 20015642–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanon O, Forette F. Prevention of dementia: lessons from SYST‐EUR and PROGRESS. J Neurol Sci 200422671–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rozzini L, Chilovi B V, Bertoletti E.et al Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors modulate the rate of progression of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 200621550–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rozzini L, Vicini Chilovi B, Bellelli G.et al Effects of cholinesterase inhibitors appear greater in patients on established antihypertensive therapy. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 200520547–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forette F, Seux M L, Staessen J A.et al The prevention of dementia with antihypertensive treatment: new evidence from the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst‐Eur) study. Arch Intern Med 20021622046–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Das U N. Is angiotensin‐II an endogenous pro‐inflammatory molecule? Med Sci Monit 200511RA155–RA162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kehoe P G, Russ C, McIlory S.et al Variation in DCP1, encoding ACE, is associated with susceptibility to Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet 19992171–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lehmann D J, Cortina‐Borja M, Warden D R.et al Large meta‐analysis establishes the ACE insertion‐deletion polymorphism as a marker of Alzheimer's disease. Am J Epidemiol 2005162305–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simons M, Keller P, De Strooper B.et al Cholesterol depletion inhibits the generation of beta‐amyloid in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998956460–6464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chandra V, Pandav R. Gene‐environment interaction in Alzheimer's disease: a potential role for cholesterol. Neuroepidemiology 199817225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kivipelto M, Helkala E L, Laakso M P.et al Midlife vascular risk factors and Alzheimer's disease in later life: longitudinal, population based study. BMJ 20013221447–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lesser G, Kandiah K, Libow L S.et al Elevated serum total and LDL cholesterol in very old patients with Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 200112138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masse I, Bordet R, Deplanque D.et al Lipid lowering agents are associated with a slower cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005761624–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jick H, Zornberg G L, Jick S S.et al Statins and the risk of dementia. Lancet 20003561627–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolozin B, Kellman W, Ruosseau P.et al Decreased prevalence of Alzheimer disease associated with 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methyglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Arch Neurol 2000571439–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zamrini E, McGwin G, Roseman J M. Association between statin use and Alzheimer's disease. Neuroepidemiology 20042394–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hajjar I, Schumpert J, Hirth V.et al The impact of the use of statins on the prevalence of dementia and the progression of cognitive impairment. J Gerontol A, Biol Sci Med Sci 200257M414–M418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sparks D L, Sabbagh M N, Connor D J.et al Atorvastatin for the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: preliminary results. Arch Neurol 200562753–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davignon J, Laaksonen R. Low‐density lipoprotein‐independent effects of statins. Curr Opin Lipidol 199910543–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaesemeyer W H, Caldwell R B, Huang J.et al Pravastatin sodium activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase independent of its cholesterol‐lowering actions. J Am Coll Cardiol 199933234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stuve O, Youssef S, Steinman L.et al Statins as potential therapeutic agents in neuroinflammatory disorders. Curr Opin Neurol 200316393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Etminan M, Gill S, Samii A. Effect of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs on risk of Alzheimer's disease: systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies. BMJ 2003327128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aisen P S, Schafer K A, Grundman M.et al Effects of rofecoxib or naproxen vs placebo on Alzheimer disease progression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 20032892819–2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scharf S, Mander A, Ugoni A.et al A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of diclofenac/misoprostol in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 199953197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aisen P S, Schmeidler J, Pasinetti G M. Randomized pilot study of nimesulide treatment in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 2002581050–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ritchie C W, Ames D, Clayton T.et al Metaanalysis of randomized trials of the efficacy and safety of donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine for the treatment of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 200412358–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaduszkiewicz H, Zimmermann T, Beck‐Bornholdt H P.et al Cholinesterase inhibitors for patients with Alzheimer's disease: systematic review of randomised clinical trials. BMJ 2005331321–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]