Abstract

Background

Intraventricular rupture of brain abscesses (IVRBA) remains a catastrophic and fatal complication of bacterial brain abscess (BBA). However, no information has been reported about the risk factors that are predictive of intraventricular rupture.

Methods

This study was undertaken to determine the potential risk factors that are predictive of intraventricular ruptures in patients with BBA but without intraventricular rupture when arriving at the hospital. A comparison is also made between patients who already have IVRBA at the time of admission (initial IVRBA) and those who have the episode during hospitalisation (subsequent IVRBA).

Results

62 patients, including 45 who had initial IVRBA and 17 who had subsequent IVRBA, were examined. Stepwise logistic regression analysis showed that the adjusted risk of intraventricular rupture during hospitalisation for patients with multiloculated brain abscesses had an odds ratio (OR) of 4.2 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.24 to 14.3; p = 0.02) compared with those without multiloculated brain abscesses (referent); a reduction of 1 mm in the distance between the ventricle and brain abscesses would increase the rupture rate by 10% (p = 0.006, OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.97).

Conclusion

This study shows that if the abscess is deep seated, multiloculated and close to the ventricle wall, a reduction of 1 mm in the distance between the ventricle and brain abscesses will increase the rupture rate by 10%. Despite aggressive medical and surgical management shown in this series, many patients continue to progress poorly.

Despite the advent of modern neurosurgical techniques, new antibiotics and new powerful imaging modalities, intraventricular rupture of brain abscesses (IVRBA) remains a catastrophic and fatal complication of bacterial brain abscesses (BBA).1,2,3 To our knowledge, only one piece of clinical research has focused specifically on BBA complicating intraventricular ruptures.1 Owing to the possible benefit of therapeutic intervention, there is a need for a better delineation of the potential risk factors and clinical features in this specific group of patients.

Hospital‐based studies provide accurate information on the localisation of brain abscesses, predisposing factors, clinical features, the prevalence rate of implicated bacterial pathogens and the causes of death. This study was undertaken to examine (1) the clinical features relevant to IVRBA; (2) the risk factors that are predictive of intraventricular ruptures; and (3) our clinical experience in the treatment of patients with IVRBA.

Patients and methods

Over a period of 20 years (1986–2005), 179 adults at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CGMH)‐Kaohsiung, Taiwan, were retrospectively identified as having BBA using pre‐existing standardised evaluation forms. CGMH‐Kaohsiung is a 2482‐bed acute‐care teaching hospital, which provides both primary and tertiary referral care to patients and is the largest medical centre in southern Taiwan. Of the 179 patients, 62 had IVRBA; 45 of the 62 patients already had IVRBA at the time of admission (initial IVRBA) and the remaining 17 had the episode during hospitalisation (subsequent IVRBA).

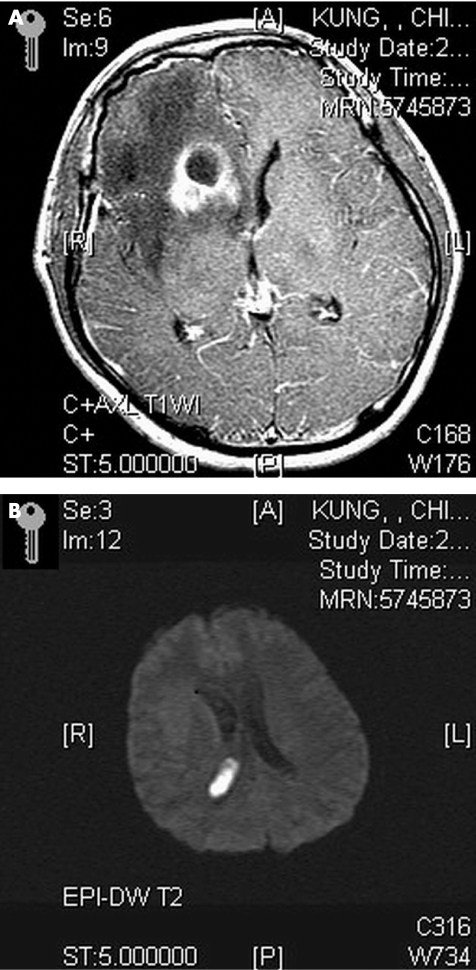

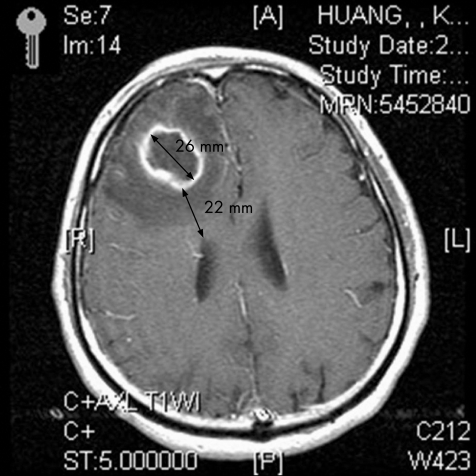

The inclusion criteria of BBA were as follows: (1) characteristic findings on computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); (2) evidence of brain abscesses seen during surgery or histopathological examination; and (3) classical clinical manifestations and symptomatology, including headache, fever, localised neurological signs and/or altered consciousness.4,5,6,7 Furthermore, the term IVRBA used in this study was slightly modified from previous studies,1,8 defined as deterioration in the clinical status of a patient, with ensuing semicoma or coma, and shown by a diffusely enhanced ventricular wall on contrast‐enhanced computed tomography or MRI (fig 1A,B). “Diameter of brain abscess” indicates the maximum diameter of the abscess; it indicates the abscess having the closest proximity to the ventricle if at least two brain abscesses are found. Furthermore, “nearest distance between ventricle and brain abscess” indicates the minimum distance between the ventricle and inner margin of the abscess, which is closest to the ventricle if at least two brain abscesses are found (fig 2).

Figure 1 (A) Magnetic resonance imaging axial view T1‐weighted image with gadolinium‐diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid administration shows a ring‐enhancing lesion in the right frontal horn, and increased enhancement in the leptomeninges and periventricular region. (B) Diffusion‐weighted image shows a hyperintense lesion in the right lateral ventricle consistent with intraventricular debris.

Figure 2 Magnetic resonance imaging axial view T1‐weighted image with gadolinium‐diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid administration shows a ring‐enhancing lesion in the right frontal lobe. The nearest distance to the frontal horn and maximum diameter of the abscess are about 22 and 26 mm, respectively.

All material from the BBA was cultured for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, Mycobacterium and fungi. Antibiotic susceptibility was determined using the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method (Mueller–Hinton II agars; Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Maryland, USA). Appropriate antimicrobial treatment was defined as the administration of one or more antimicrobial agents that were effective against bacterial pathogens, and were capable of passing through the blood–brain barrier in adequate amounts. Patients were considered to have mixed infection if at least two bacterial organisms were isolated from the initial cultures.

A combination of surgical intervention and antibiotic treatment was the mainstay of our treatment of BBA. In our institution, the surgical management of brain abscesses consists of image‐guided stereotactic aspiration or craniotomy with complete excision. Aspiration was used to aspirate the content of the abscess with a ventricular catheter through a burr hole or by performing small craniotomy, which left the capsule alone. Craniotomy and resection of the abscess was defined as excision. The choice of one procedure over another may have been influenced by the age of the patient, neurological condition, location and stage of the abscess, type of abscess and whether multiple lesions were present. Stereotactic aspiration is the simplest and safest method to obtain pus for culture. It allows precise localisation and decompression of the abscess cavity using a minimally invasive technique. It is valuable in treating deep‐seated lesions, lesions in eloquent areas and multiple abscesses. Many surgeons favour excision for solitary abscess recurrence in the non‐eloquent cerebral cortex with mature capsule. The combination of third‐generation cephalosporins and metronidazole is the mainstay of initial empirical antimicrobial treatment of BBA. The choice of final antibiotics was guided by the final culture results. Therapeutic outcome was evaluated at a 3‐month end point, according to the Glasgow Outcome Score as follows: grade 1, good recovery; grade 2, moderate disability; grade 3, severe disability; grade 4, persistent vegetative state; and grade 5, death.9

In this study, we examined the potential risk factors that are predictive of intraventricular ruptures in those patients who had BBA without intraventricular rupture when arriving to the hospital. To avoid interference with statistical analysis, the 45 patients who already had IVRBA at the time of admission were excluded. Clinical data, including sex and clinical manifestations between the two patient groups (without IVRBA and subsequent IVRBA during hospitalisation), were analysed by means of the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. The mean age, the diameter of BBAs, the distance between the ventricular wall and the nearest margin of BBAs, and the interval between diagnosis of BBAs and intraventricular rupture between the two patient groups were logarithmically transformed to improve normality, and comparisons between the two patient groups were made using Student's t test. Stepwise logistic regression was used to evaluate the relationships between risk factors and the presence of intraventricular rupture, with adjustments made for other potential confounding factors. All statistical analysis was conducted using SAS software package, version 9.1 (2002, SAS Statistical Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Tables 1–4 list the clinical, underlying diseases, laboratory and neuroimaging data of the 179 enrolled IVRBA cases. There were 62 patients with IVRBA: 44 men (mean age 47 years; range 4–76 years) and 18 women (mean age 47.4 years; range 5–73 years). Mean age was 47.3 (standard deviation (SD) 19.9) years for those patients who had initial IVRBA and 46.8 (15.1) years for those who had subsequent IVRBA (p = 0.925, Student's t test; table 1).

Table 1 Demographic features of patients with intraventricular rupture of brain abscesses.

| Initial IVRB | Subsequent IVRBA | Non‐IVRBA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 45 | n = 17* | n = 117 | |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 47.3 (19.9) | 46.8 (15.1) | 43.8 (18.5) |

| Sex (male/female) | 31/14 | 13/4 | 91/26 |

| Clinical features | |||

| Fever/chills | 31 | 12 | 65 |

| Disturbed consciousness | 26 | 9 | 48 |

| Headache | 23 | 7 | 65 |

| Hemiparesis | 19 | 8 | 54 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 14 | 6 | 25 |

| Stiff neck | 15 | 2 | 31 |

| Speech disturbance | 8 | 4 | 16 |

| Septic shock | 9 | 1 | 11 |

| Seizure | 6 | 2 | 20 |

| Visual disturbance | 2 | 1 | 20 |

| Facial palsy | 2 | 0 | 9 |

| Associated with meningitis | 18 | 7 | 37 |

| Median (range) GCS on presentation | 12 (5–15) | 13.5 (8–15) | 9 (4–15) |

| Median (range) preoperative GCS | 12 (5–15) | 9.5 (3–15) | 10.5 (4–15) |

| Median (range) postoperative GCS (48 h) | 14 (4–15)† | 14 (3–15)‡ | 10.5 (3–15) |

| Mean (SD) hospitaliation (days) | 48.7 (31.6) | 61 (49.1) | 37.3 (27.8) |

| Median (range) GOS at 3‐month end point | 2 (1–5) | 3 (1–5) | 2 (1–5) |

| Good recovery | 21 | 4 | 46 |

| Moderate disability | 5 | 2 | 17 |

| Severe disability | 5 | 5 | 18 |

| Vegetative state | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Death | 12 | 5 | 31 |

GCS, Glasgow Coma Score; GOS, Glasgow Outcome Score; IVRBA, intraventricular rupture of brain abscesses.

*15 patients had deterioration in clinical status during hospitalisation.

†Eight patients received conservative treatment.

‡One patient received conservative treatment.

Table 2 Underlying conditions of patients with intraventricular rupture of brain abscesses.

| Underlying conditions | Initial IVRBA | Subsequent IVRBA | Non‐IVRBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 45* | n = 17† | n = 117‡ | |

| Postneurosurgical state/head trauma | 11 | 6 | 30 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 | 3 | 18 |

| Chronic otitis media | 4 | 1 | 15 |

| Congenital heart disease | 8 | 0 | 15 |

| Alcoholism or liver cirrhosis | 2 | 2 | 15 |

| Neoplasm | 3 | 2 | 10 |

| Stroke | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| CSF leakage | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| ESRD | 0 | 0 | 3 |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ESRD, end‐stage renal disease; IVRBA, intraventricular rupture of brain abscesses.

*In initial IVRBA, 30 patients had more than one underlying disease.

†In subsequent IVRBA, 12 patients had more than one underlying disease.

‡In non‐IVRBA, 78 patients had more than one underlying disease.

Table 3 Causative pathogens of bacterial brain abcess.

| Initial IVRBA | Subsequent IVRBA | Non‐IVRBA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 45 | n = 17 | n = 117 | |

| Gram‐negative bacilli (n = 39) | |||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 5 | 1 | 12 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Escherichia coli | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Other* | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| Streptococcus species (n = 27) | |||

| Streptococcus viridans | 7 | 3 | 15 |

| Other† | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Staphylococcus species (n = 10) | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Coagulase‐negative Staphylococcus | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Anaerobes (n = 24) | |||

| Fusobacterium species | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Bacteriodes species | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| Peptostreptococcus species | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Other‡ | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Mixed infection (n = 23) | 8 | 2 | 13 |

| Negative culture (n = 56) | 9 | 4 | 43 |

IVRBA, intraventricular rupture of brain abscesses.

*Other Gram‐negative bacilli included Salmonella species (2), Serratia marcescens (2), Klebsiella oxytoca (1), Vibrio cholerae non‐O1 (1), Proteus mirabilis (1) and Pasteurella species (1).

†Other streptococci included non‐A, non‐B and non‐D streptococci (1) and Group B Streptococcus (1).

‡Other anaerobes included Corynebacterium species (3), Peptococcus species (2) and Propriobacterium acne (1).

Table 4 Neuroimaging findings of patients with intraventricular rupture of brain abscesses.

| Initial IVRBA | Subsequent IVRBA | Non‐IVRBA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 45 | n = 17 | n = 117 | |

| Location and number of abscesses | |||

| Single | |||

| Frontal lobe | 13 (6) | 4 (1) | 31 (6) |

| Temporal lobe* | 4 (1) | 3 | 16 (3) |

| Temporoparietal area* | 6 (1) | 1 (1) | 6 (1) |

| Basal ganglion* | 3 | 1 (1) | 6 |

| Parieto‐occipital area | 2 (1) | 1 | 11 (2) |

| Frontoparietal area* | 2 | 1 | 19 (2) |

| Occipital lobe* | 1 | 1 | 6(2) |

| Parietal lobe* | 1 | 1 (1) | 10 (3) |

| Thalamus | 2 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Cerebellum* | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Multiple sites | 10 (5) | 4 (3) | 4 |

| Diameter of brain abscess (mm) | 43.8 (18.2) | 31.2 (14.6)† | 34.5 (18.1) |

| Ventricular debris | 33 | 11 | 0 |

| Hydrocephalus | 26 | 4‡ | 13 |

| Ependymal enhancement | 40 | 16 | 22 |

| Septation of the ventricle | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Meningeal enhancement | 20 | 8 | 42 |

IVRBA, intraventricular rupture of brain abscesses.

*Case numbers of multilocuated brain abscesses are shown in parentheses.

†Diameter of brain abscess initially at the time of admission.

‡Hydrocephalus initially at the time of admission.

The mean interval from the onset of symptoms to the detection of brain abscesses was 14.5 days for initial IVRBA and 10.4 days for subsequent IVRBA (p = 0.228, Student's t test). The median (range) Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) total score for the time of admission was 12 (5–15) for patients who had initial IVRBA and 13.5 (8–15) for those who had subsequent IVRBA (p = 0.324, Wilcoxon's rank sum test). The median preoperative GCS total score was 12 (5–15) for patients who had initial IVRBA and 9.5 (3–15) for those who had subsequent IVRBA (p = 0.095, Wilcoxon's rank sum test). The median postoperative 48‐h GCS total score was 14 (4–15) for those patients who had initial IVRBA and 14 (3–15) for those who had subsequent IVRBA (p = 0.234, Wilcoxon's rank sum test). The mean (SD) duration of hospitalisation was 48.7 (31.6) days in patients with initial IVRBA and 61 (49.1) days in patients with subsequent IVRBA (p = 0.387, Student's t test logarithmically transformed to improve normality).

The portal of entry for infection in 62 BBA cases included haematogenous spread (n = 24), postneurosurgical states (n = 16), contiguous infection from parameningeal foci such as an otogenic origin (n = 4), paranasal sinusitis (n = 2) and periodonditis (n = 4), and unknown (n = 12). Table 3 lists the causative pathogens of BBA in these 62 patients. Table 1 lists the clinical manifestations of these 62 patients. In all, 35 patients were admitted with disturbed consciousness, 26 of whom had initial IVRBA, whereas the other 9 had subsequent IVRBA; 15 of the 17 patients who had subsequent IVRBA had sudden deterioration in clinical status during hospitalisation. Concomitant bacterial meningitis was found in 25 patients, 18 of whom had initial IVRBA, whereas the other 7 had subsequent IVRBA.

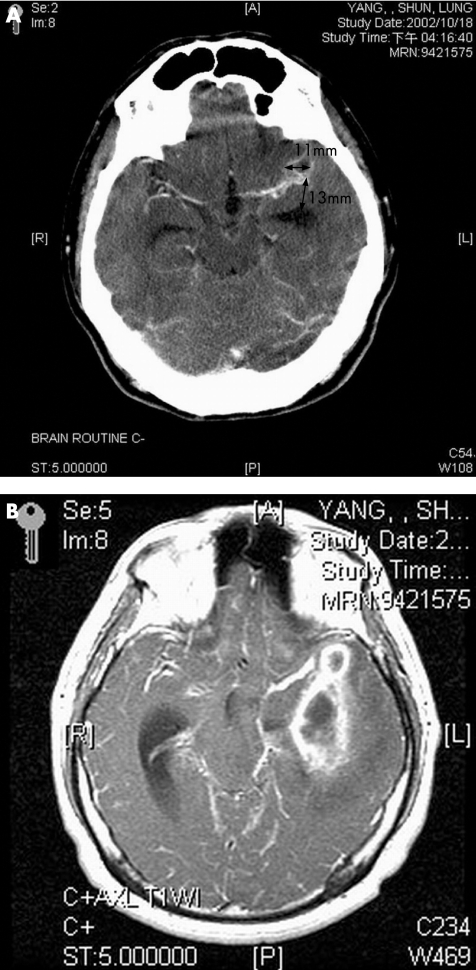

Table 4 lists the neuroimaging findings of these 62 cases (fig 3A,B). The abnormal neuroimaging findings included hydrocephalus in 30, ependymal enhancement in 56, septation of the ventricle in 3, meningeal enhancement in 28 and ventricular debris in 44. The mean (SD) diameter of initial brain abscesses at the time of admission was 43.8 (18.2) mm in initial IVRBA and 31.2 (14.6) mm in subsequent IVRBA (p = 0.013, Student's t test). Except for one case, the brain abscesses of the other 61 cases were located in the supratentorial location (table 4). In total, 48 (77.4%) had a single brain abscess and 14 (22.6%) had multiple brain abscesses. The 48 patients included uniloculated abscesses in 35 and multiloculated abscesses in the remaining 13. The latter 14 included uniloculated abscesses in 6 and multiloculated abscesses in the remaining 8. The most common sites for brain abscesses were the frontal lobe, followed by the temporal lobe and temporoparietal lobe.

Figure 3 A 34‐year‐old man presented with postneurosurgical central nervous system infection, with an initial Glasgow Coma Score of E3V4M6. (A) Computed tomography scan of the brain with intravenous contrast administration showing a small ring‐enhanced lesion in the left Sylvian fissure region. (B) Magnetic resonance imaging axial view T1‐weighted image with gadolinium administration performed 1 month later showing multiloculated enhanced lesions in the left temporal region touching the ventricular wall of the temporal horn.

Antimicrobial treatment with surgical intervention (aspiration or total excision) was the cornerstone of treatment in 53 patients. Nine patients received antimicrobial treatment alone because they had poor systemic condition. There were six deaths among these nine patients. Of 28 patients who received both antimicrobial treatment and total excision, 6 died. Of 25 patients who received both antimicrobial treatment and aspiration, 5 died. Therapeutic outcome among these 62 patients at 3 months was determined by the Glasgow Outcome Score (GOS) with 25 having good recovery (40.3%, 25/62), 7 having moderate disability (11.3%, 7/62), 10 having severe disability (16.1%, 10/62), 3 having persistent vegetative state (4.9%, 3/62) and 17 dying (27.4%, 17/62). The overall mortality for patients who had initial IVRBA and those who had subsequent IVRBA was 26.7% (12/45) and 29.4% (5/17), respectively. The median (range) GOS was 2 (1–5) for patients who had initial IVRBA and 3 (1–5) for those who had subsequent IVRBA (p = 0.208, Wilcoxon's rank sum test).

Table 5 lists the comparative results of clinical features and neuroimaging findings between the patient groups with or without intraventricular rupture. Statistical analysis of the clinical manifestations and laboratory data between the two patient groups shows the following significant findings: presence of multiloculation (p = 0.045), and the nearest distance between the margin of brain abscesss and ventricle walls (p = 0.001). Significant univariate factors and possible confounding factors used in stepwise logistic regression included age, sex, presence of multiloculation and the nearest distance between the margin of brain abscesses and ventricle walls. The results show that after analysis of all the above‐mentioned variables, the adjusted risk of intraventricular rupture during hospitalisation for patients with multiloculated brain abscesses is equal to 4.2 (OR) (95% CI 1.24 to 14.3, p = 0.02) compared with those who do not (referent); a reduction of 1 mm in the distance between ventricle walls and abscesses will increase the rupture rate by 10% (p = 0.006, OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.97).

Table 5 Comparison of clinical features and neuroimaging findings between bacterial brain abscesses with or without intraventricular rupture.

| Subsequent IVRBA n = 17 | Without IVRBA n = 117 | p Value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 13/4 | 91/26 | 1 | 1.08 | 0.32 to 3.58 |

| Mean age (years) | 46.8 (15.1) | 43.8 (18.5) | 0.468 | ||

| Mental state at the time of admission | |||||

| Clear consciousness (GCS = 15) | 8 | 69 | 0.353 | 0.618 | 0.22 to 1.71 |

| Disturbed consciousness (GCS<15) | 9 | 48 | |||

| Mean (SD) duration between onset of symptoms and diagnosis of abscess | 10.4 (12.1) | 15.2 (22.7) | 0.518 | ||

| Underlying diseases | |||||

| Congenital heart disease | 0 | 15 | 0.216 | 0.87 | 0.81 to 0.93 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 | 18 | 0.733 | 1.17 | 0.3 to 4.48 |

| Alcoholism/liver cirrhosis | 2 | 15 | 1 | 0.91 | 0.18 to 4.37 |

| Chronic otitis media | 1 | 15 | 0.692 | 0.43 | 0.05 to 3.44 |

| Postneurosurgical state | 6 | 30 | 0.394 | 1.582 | 0.54 to 4.65 |

| Clinical features | |||||

| Fever | 12 | 65 | 0.241 | 1.92 | 0.64 to 5.8 |

| Headache | 7 | 65 | 0.267 | 0.56 | 0.2 to 1.57 |

| Hemiparesis | 8 | 54 | 0.944 | 1.04 | 0.37 to 2.87 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 6 | 25 | 0.224 | 2.01 | 0.68 to 5.96 |

| Neck stiffness | 2 | 31 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.08 to 1.71 |

| Seizure | 2 | 20 | 0.738 | 0.65 | 0.14 to 3.05 |

| Hydrocephalus | 4 | 13 | 0.232 | 2.46 | 0.7 to 8.68 |

| Septic shock | 1 | 11 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.07 to 4.99 |

| Visual disturbance | 1 | 20 | 0.472 | 0.3 | 0.04 to 2.42 |

| Papilloedema | 0 | 7 | 0.595 | 0.42 | 0.02 to 7.7 |

| Hemiparesthesia | 8 | 54 | 0.287 | 1.04 | 0.37 to 2.87 |

| Associated with meningitis | 7 | 37 | 0.433 | 1.51 | 0.53 to 4.29 |

| Portal of entry | |||||

| Haematogenous spread | 6 | 34 | 0.6 | 1.332 | 0.46 to 3.89 |

| Non‐haematogenous spread | 11 | 83 | |||

| Acquisition of infection | |||||

| Nosocomially acquired | 6 | 31 | 0.562 | 1.51 | 0.52 to 4.44 |

| Community acquired | 11 | 86 | |||

| Neuroimaging findings | |||||

| Mean (SD) nearest distance between the ventricular wall and margin of brain abscess | 11.1 (10.1) | 19.1 (9.7) | 0.001 | ||

| Mean (SD) size of the nearest brain abscess | 31.2 (14.6) | 34.5 (18.1) | 0.571 | ||

| Multiloculation | 7 | 20 | 0.045 | 3.36 | 1.15 to 9.99 |

| Mortality | 5 | 32 | 1 | 1.11 | 0.36 to 3.39 |

| Median (range) GOS at 3‐month end point | 3 (1–5) | 2 (1–5) | 0.276 |

GCS, Glasgow Coma Score; GOS, Glasgow Outcome Score; IVRBA, intraventricular rupture of brain abscesses.

DISCUSSION

The exact incidences of IVRBA vary with the time period, different diagnostic tools, causative pathogens, age, underlying medical and/or surgical conditions, and mode of infection10,11,12,13; its reported frequency varies from 0% to 31%.10,11,12,13 In this study, it accounted for 34.6% (62/179) of our BBA cases. Furthermore, IVRBA is less commonly described in the literature,1 and most reports are summarised under diverse BBAs10,11,12,13 or case report studies.2,14,15,16

IVRBA is a devastating and often fatal complication of BBA, associated with high mortality.12,13 One study searched, from 1950 to 1993, for both series of reported BBAs and case reports of IVRBA, showing that the overall mortality is 84.5% (109/129).14 Another recent study from Japan showed that the overall mortality is 38.7% (12/31).17 In our study, the overall mortality was 27.4% (17/62). However, if we take into account those with poor outcome (severe disabilities, vegetative states and death), 48% (30/62) of patients could be considered treatment failures.

Although abscess encapsulation is influenced by a number of factors, which include (1) the offending organism; (2) the origin of infection (direct extension v metastatic); (3) the immune status of the host; (4) corticosteroid administration; and (5) antibiotic treatment,18 when haematogenous spread is the source of the brain abscesses, the abscesses are often deep seated and are detected at the white matter–grey matter junction with poor capsule formation. Haematogenous spread from a distant focus is an important cause of IVRBA in other studies1 (93.9%, 31/33) and in our study (38.7%, 24/62). Although postneurosurgical states were once unusual as a cause of IVRBA,1 our study also shows a high proportion of postneurosurgical states (27.4%, 17/62) as the portal of entry in patients with IVRBA. The increasing frequency of neurosurgical procedures may be due to the increasing number of neurosurgeons and the large number of patients with head injuries from motorcycle accidents.

The clinical features already mentioned can be indistinguishable from those of BBAs without intraventricular rupture, except for severe headache with signs of meningeal irritation and rapid deterioration of clinical conditions.1 In our study, signs of meningeal irritation between patients with or without intraventricular rupture were not important because 34.6% (62/179) of our cases were concomitant with meningitis. In this study, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Streptococcus viridans were the most common causative pathogens of BBA. In Taiwan, Klebsiella infection has been known to commonly cause invasive infection, including metastatic septic abscesses, bacteraemia, pneumonia, endophthalmitis and meningitis.19,20Streptococcus viridans has been known as one of the prevalent pathogens with haematogenous spread secondary to infectious endocarditis, especially in individuals with pre‐existing native valvular disease, or on prosthetic valves, and it also may invade the bloodstream after medical procedures to complicate infections at other sites.21 Therefore, it may partly explain the high proportion of cases associated with meningitis in our study. Furthermore, deterioration in clinical status during hospitalisation was the consistent finding in patients who had subsequent IVRBA, and these signs are often overlooked. Accordingly, if patients who have BBAs develop deterioration of consciousness, IVRBA should be suspected.

Regarding the neuroimaging findings, one study showed that in the parieto‐occipital area, deeped‐seated abscesses are prone to intraventricular rupture, and other factors such as number of abscesses and size of abscesses are not predictive of intraventricular rupture.1 By contrast, in most of our cases, the frontotemporal location was involved. Our study shows that it is the (1) morphology of the abscess and (2) the distance between abscesses and the ventricle walls, but not the size of abscesses, that are predictive of intraventricular rupture. Furthermore, our study shows that the adjusted risk of intraventricular rupture during hospitalisation for patients who have multiloculated brain abscesses is 4.2 times greater than among those who do not; and also that a reduction of 1 mm in the distance between the ventricle and brain abscesses increases the rupture rate by 10%.

Although a combination of intrathecal and intravenous antimicrobial treatment has been recommended in IVRBA,22 the therapeutic strategy in this special group of patients remains controversial. Other therapeutic regimens have been recommended, including (1) urgent craniotomy with rapid evacuation of the abscess12; (2) emergent evacuation with lavage of the ventricles and ventriculostomy placement accompanied by the administration of intraventricular antibiotics23; and (3) a five‐component therapeutic regimen, including open craniotomy with debridement of the abscess cavity, lavage of the ventricle system, intravenous administration of antibiotics for 6 weeks, intraventricular administration of gentamicin twice daily for 6 weeks and intraventricular drainage for 6 weeks.14 As this is a retrospective study, the therapeutic strategies would be different for each patient according to the preference of his or her doctor, which may cause a potential bias in statistical analysis and when drawing conclusions. Therefore, we look forward to more prospective multicentre investigations in evaluating the efficiency of treatment in the future.

In summary, our study shows that if the abscess is deep seated, multiloculated and close to the ventricle wall, a reduction of 1 mm in the distance between the ventricle and brain abscesses will increase the rupture rate by 10%. Despite aggressive medical and surgical management in this series, many patients progress poorly.

Abbreviations

BBA - bacterial brain abscess

CGMH - Chang Gung Memorial Hospital

GCS - Glasgow Coma Score

GOS - Glasgow Outcome Score

IVRBA - intraventricular rupture of brain abscesses

MRI - magnetic resonance imaging

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Takeshita M, Kawamata T, Izawa M.et al Prodromal signs and clinical factors influencing outcome in patients with intraventricular rupture of purulent brain abscess. Neurosurgery 200148310–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isono M, Wakabayashi Y, Nakano T.et al Treatment of brain abscess associated with ventricular rupture—three case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 199737630–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyamoto Y, Kyoshima K, Takeichi Y. Intraventricular rupture of brain abscess: report of 3 cases including 2 survivals. Nippon Geka Hokan 198857233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathisen G E, Johnson J P. Brain abscess. Clin Infect Dis 199725763–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garner J S, Jarvis W R, Emori T G.et al CDC definitions for nosocomial infections. Am J Infect Control 198816128–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.New P F, Davis K R, Ballantine H T., Jr Computed tomography in cerebral abscess. Radiology 1976121641–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haimes A B, Zimmerman R D, Morgello S.et al MR imaging of brain abscesses. Am J Roentgenol 19891521073–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reed J E, Williams J P, Cooper M D. Intraventricular abscess rupture. Neuroradiology 19747261–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marion D W. Complications of head injury and their therapy. Neurosurg Clin Am 19912411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mampalam T J, Rosenblum M L. Trends in the management of bacterial brain abscesses: a review of 102 cases over 17 years. Neurosurgery 198823451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seydoux C, Francioli P. Bacterial brain abscesses: factors influencing mortality and sequelae. Clin Infect Dis 199215394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang S Y, Zhao C S. Review of 140 patients with brain abscess. Surg Neurol 199339290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferre C, Ariza J, Viladrich P F.et al Brain abscess rupturing into the ventricles or subarachnoid space. Am J Med 1999106254–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeidman S M, Geisler F H, Olivi A. Intraventricular rupture of a purulent brain abscess: case report. Neurosurgery 199536189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamra P, Vatsal D K, Husain M.et al MRI demonstration of unsuspected intraventricular rupture of pyogenic cerebral abscesses in patients being treated for meningitis. Neuroradiology 200244114–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choudhari K A. Prodromal signs and clinical factors influencing outcome in patients with intraventricular rupture of purulent brain abscess. Neurosurgery 200149481–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeshita M, Kagawa M, Izawa M.et al Current treatment strategies and factors influencing outcome in patients with bacterial brain abscess. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 19981401263–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su T M, Lan C M, Tsai Y D.et al Multiloculated pyogenic brain abscess: experience in 25 patients. Neurosurgery 2003521075–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liliang P C, Lin Y C, Su T M.et al Klebsiella brain abscess in adults. Infection 20012981–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu C H, Chang W N, Chang H W. Klebsiella meningitis in adults: clinical features, prognostic factors and therapeutic outcomes. J Clin Neurosci 20029533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su T M, Lin Y C, Lu C H.et al Streptococcal brain abscess: analysis of clinical features in 20 patients. Surg Neurol 200156189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brewer N S, MacCarty C S, Wellman W E. Brain abscess: a review of recent experience. Ann Intern Med 197582571–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Black P M, Levine B W, Picard E H.et al Asymmetrical hydrocephalus following ventriculitis from rupture of a thalamic abscess. Surg Neurol 198319524–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]