Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis (PLE) is a rare neurological syndrome characterised by short‐term memory impairment, seizures and various psychiatric disturbances. It is often associated with small‐cell lung cancer, germ‐cell tumours of the testis and breast cancer, but rarely with ovarian teratoma.1 Several cases of PLE with ovarian teratoma have been reported, but the autoantigens of this disease remain unknown. Recently, an antibody to the membranes of neurones of the hippocampus (antigens colocalising with exchange factor for ADP‐ribosylation factor 6 A (EFA6A)) was reported in association with PLE and ovarian teratoma.2 Here, we report a case of a young Japanese woman who had PLE with ovarian teratoma, and whose serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contained an antibody against the membranes of neurones of the hippocampus. Immunosuppressive treatments resulted in a rapid improvement.

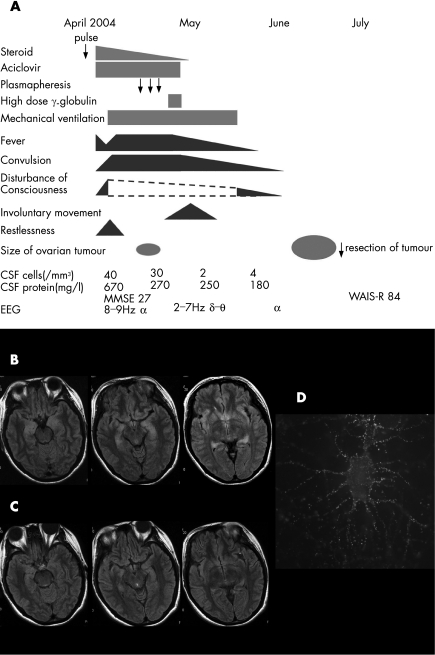

A 30‐year‐old woman was admitted to our hospital (Jichi Medical University, Tochigi, Japan) in April 2004 because of headache, fever and disorientation for 3 days. Figure 1A summarises the clinical course of the patient. She had no relevant family or medical history of interest. Her temperature was 37.8°C. Neurological examination on admission showed only recent memory disturbance. Examination of CSF showed increased protein concentration (670 mg/l), an increased number of mononuclear‐dominant cells (40/mm3) and 67 mg/dl glucose. CSF cytology was negative for malignant cells. Polymerase chain reaction for herpes simplex virus (HSV) was negative. No marked increase in anti‐HSV, varicella zoster virus, human herpes virus type 6, cytomegalovirus or Epstein–Barr virus antibodies was detected in a paired CSF sample. Anti‐toxoplasma and Japanese encephalitis virus antibodies were negative in the serum. The serum did not contain increased anti‐nuclear, double‐strand DNA, SS‐A or thyroid antibodies. Anti‐Yo, anti‐Hu, anti‐Ri, anti‐CV2 (CRMP‐5), anti‐Tr, anti‐Ma‐2 and amphyphysin antibodies were negative in serum and CSF. Anti‐voltage‐gated potassium channel antibodies were not detected. Although axial plane and gadolinium‐enhanced T1‐weighted magnetic resonance images (MRI) were unremarkable, T2‐weighted and fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery images showed areas of mild hyperintensity in bilateral medial temporal lobes and hippocampus (fig 1B); these abnormalities had resolved by the time of the follow‐up study in June 2004 (fig 1C).

Figure 1 Clinical course of the patient, magnetic resonance image of the brain and immunolabelling of live rat hippocampal neurones with the patient's cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). (A) Clinical course of the patient. The symptoms and laboratory data were improved before the tumour resection. (B) MRI fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery images of the brain in April 2004 showed areas of hyperintensity in the medial temporal lobes, cingulate gyrus, insular regions and hippocampus. (C) These abnormalities had resolved by June 2004. (D) The patient's antibodies, which colocalised with EFA6A, showed intense immunolabelling of the neuronal cell membranes and processes, using methods previously reported2. WAIS‐R, Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised.

Initial treatments included methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day for 3 days) and aciclovir (1500 mg/day). This treatment was associated with mild and transient decrease of fever, but tonic convulsions, disturbance of consciousness, restlessness and anxiety emerged and became worse. The electroencephalogram showed diffuse δ–θ waves. These symptoms and hypoventilation led to her being sedated and on a mechanical ventilator for 6 weeks with anticonvulsant treatment. Anisocoria, skew deviation and involuntary movement, such as epilepsia partialis continua, were observed for 2 weeks. Several attempts to wean the patient from the ventilator and decrease the sedation resulted in exacerbation of the involuntary movements and hypoventilation. Subsequently, the patient was treated with plasmapheresis (three exchanges) and intravenous immunoglobulin (400 mg/kg/day) for 5 days. The fever and convulsions began to subside about 4 weeks after her admission. She could breath spontaneously and all CSF studies became normal in May 2004.

In April 2004, an abdominal computed tomography had shown a 5 cm tumour in the right ovary, which was considered a benign cyst unrelated to the neurological disorder. In June 2004, the patient developed progressive constipation and a bulging appearance of the lower abdomen. Follow‐up abdominal computed tomography and MRI showed an enlarged ovarian tumour, with a transverse diameter of 10 cm. On 28 June, resection of the tumour showed an immature teratoma that contained hair follicles, cartilage tissue, glandular structures and cerebral cortex‐like tissue with normal appearing neurones. No inflammatory infiltrates were evident in the tumour.

Although her Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised score was 84, she recovered and exhibited no limitations in activity of daily living in July 2004. After she was discharged from our hospital in July, she received ambulatory neurocognitive rehabilitation. She refused follow‐up Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised, but otherwise the cognitive functions and electroencephalogram appeared normal. She returned to her job as a medical resident in April 2005.

Analysis of the patient's serum and CSF showed antibodies, colocalised with EFA6A, which predominantly reacted with the neuropil of the hippocampus and cell membrane of rat hippocampal live neurones (fig 1D).

Discussion

We consider that this patient had definite paraneoplastic encephalitis, with predominant involvement of the limbic system. Accordingly, she developed subacute onset of short‐term memory loss, seizures, psychiatric symptoms, CSF pleocytosis, MRI abnormalities in the limbic system and antineural antibodies.3 Central nervous system tissue in the teratoma might be a trigger of the immune reaction. Central hypoventilation, skew deviation and anisocoria were observed during the most critical period. These symptoms suggest the involvement of her brain stem.

Previous reports of paraneoplastic encephalitis and ovarian teratoma showed MRI abnormalities in the frontal cortex, cerebellum and brain stem, but no case exhibited the characteristic medial temporal abnormalities observed in our patient.2,4 This finding might have resulted from hippocampal inflammation related to the immune response predominantly reacting with hippocampal neurones.

Most patients with PLE and ovarian teratoma improved with resection of the teratomas.2,4 We discovered the tumour in our patient 2 weeks after presentation of the encephalitis, but the benign appearance of the tumour and her poor physical status did not prompt for tumour resection. Instead, we started treatment with corticosteroids, plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin, and she began to improve before the tumour resection. This finding suggests that immunotherapy may provide the improvement needed to undergo the procedure for patients whose poor clinical condition prevents surgery. Furthermore, our patient began to recover faster (4 weeks after admission) than any other reported cases (7–16 weeks).2 We presumed that this faster improvement resulted from the combination of immunotherapies. Immunocytochemistry with rat hippocampal live neurones showed the presence of antibodies to antigens present in the neuronal cell membranes and processes and colocalised with EFA6A, as previously reported.2 The surface localisation of the autoantigen might be one reason for the effectiveness of these immunotherapies.5

PLE with ovarian teratoma has a better prognosis than that associated with other tumours.2 Prompt detection of antibodies that colocalise with EFA6A is useful in predicting a clinical response to immunotherapy and tumour resection and a favourable outcome despite the severity of the disorder.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Keiko Tanaka, Department of Neurology, Brain Research Institute, Niigata University, and Dr Yukitoshi Takahashi, Department of Pediatrics, National Epilepsy Center, Shizuoka Institute of Epilepsy and Neurological Disorders, for measurement of the anti‐neuronal antibodies.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a Jichi Medical University Young Investigator Award.

Competing interests: None.

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the features of the case.

References

- 1.Gultekin S H, Rosenfeld M R, Voltz R.et al Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis: neurological symptoms, immunological findings and tumour association in 50 patients. Brain 20001231481–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vitaliani R, Mason W, Ances B.et al Paraneoplastic encephalitis, psychiatric symptoms, and hypoventilation in ovarian teratoma. Ann Neurol 200558594–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graus F, Delattre J Y, Antoine J C.et al Recommended diagnostic criteria for paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004751135–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koide R, Shimizu T, Koike K.et al EFA6A‐like antibodies in paraneoplastic encephalitis associated with immature ovarian teratoma: a case report. J Neuro‐Oncol. In press [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Darnell R B, Posner J B. A new cause of limbic encephalopathy. Brain 20051281745–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]