Abstract

Objective

To compare cognitive impairments in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD), to discriminate between the two entities.

Methods

10 DLB and 12 PDD consecutive patients performed a neuropsychological battery designed to assess several cognitive domains: verbal and visual memory (Delayed Matching to Sample (DMS)‐48), language, gnosia, praxia and executive functions.

Results

DLB patients had poorer performances in orientation (p<0.05), Trail Making Test A (p<0.05) and reading of names of colours in the Stroop Test (p<0.05). Their scores were also lower in the visual object recognition memory test (DMS‐48), in both immediate (p<0.05) and delayed recognition (p<0.05). No differences were observed in the other tests.

Conclusion

Despite global similarities in cognitive performances between DLB and PDD patients, we observed important differences: in particular, DMS‐48, a test of visual object recognition memory and visual storage capacity, was poorer in DLB patients.

Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) share some common clinical features, such as extrapyramidal symptoms and neuropsychological impairment.1,2,3 In practice, consensus guidelines recommend an arbitrary distinction between the two disorders based on a temporal sequence of 1 year between the presentation of extrapyramidal motor symptoms and the manifestation of dementia: PDD is diagnosed if dementia occurs belatedly in the context of well established Parkinson's disease; DLB is diagnosed when motor and cognitive signs appear during the first year of evolution.4 A key question is whether this is a meaningful distinction between the two different clinical entities.

Subtle clinical distinction in terms of cognitive pattern could prove useful for clinicians.

In this study, we compared cognitive performances in a group of patients with a clinical diagnosis of “probable” DLB with those of PDD patients. As the clinical symptoms overlap, our aim was to determine possible differences in the cognitive abilities between DLB and PDD.

Patients and methods

Patients

Ten consecutive DLB patients, evaluated in the Neuropsychological Unit of the Department of Neurology of the University Hospital of Tours, were identified based on the 2005 Consensus Guidelines for DLB,4 independent of the neuropsychological data.

All of the 12 consecutive PDD patients identified presented with the criteria of idiopathic Parkinson's disease from the outset of their disease5 and developed dementia more than 6 years after the onset of parkinsonism. To exclude DLB patients from this group, patients with repeated falls or hallucinations at the onset of the disease were excluded. All PDD patients were free of cognitive changes at intake, based on clinical evaluation.

Methods

All patients underwent structured medical, neurological and functional assessments by physicians, including the motor subscale of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). Laboratory tests to exclude treatable causes of dementia were performed. All patients underwent neuroimaging (CT or MRI) to exclude the presence of focal brain lesions. Global cognitive impairment was quantified based on the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale. All 22 patients presented with impaired instrumental daily life activities with a score of 1/4 or above.6 All tests used for clinical and neuropsychological evaluation are widely used in general practice and concern systematic evaluation of patients with dementia and extrapyramidal signs in our hospital. Thus no ethics review was required.

Neuropsychological battery

The neuropsychological battery was designed to assess a broad range of cognitive functions including the following:

—orientation: 10 items of the orientation subtest from the MMSE,7

—verbal episodic memory: Buschke Selective Reminding Test,8

—attention: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale‐Revised, digit span subtest,9

—non‐verbal memory (multiple choice version of the Benton Visual Retention Test,10 Delayed Matching to Sample (DMS)‐48,11 Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (memory),12

—language: oral naming (DO)‐80,13

—verbal fluency,14

—writing comprehension: Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination,15

—visuoconstructional skills: Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (copy),12

—visuoperceptual skills: Poppelreuter Test,16

—logic and reasoning: Raven Colored Progressive Matrices Test17 and

—executive functions: Trail Making Test,18 Stroop,19 Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test criteria20 and Frontal Assessment battery.21

Care was taken to ensure that patients with DLB were not tested during a period of marked confusion. All patients were right‐handed.

Statistical procedure

A non‐parametric Wilcoxon test was used to compare the scores between the PDD and DLB groups. Statistical software used was Statview (1998). Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to determine the test characteristics of the different variables predicting diagnosis in the PDD group.22 The ROC curves were studied for area under the curve (AUC). Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). The level of significance was set at p = 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The DLB and PDD groups (eight and seven males, respectively) did not differ significantly with regard to age (78 (9) and 81 (6) years), years of education (16 (4) and 15 (3)) or UPDRS motor score (36 (21) and 30 (16)). Duration of disease was 3 (2) and 11 (4) years in the DLB and PDD groups, respectively (p<0.01).

Motor symptoms

The DLB and PDD groups did not differ with regard to UPDRS motor score (36 (21) and 30 (16)). Motor scores should be interpreted with caution as all PDD patients were receiving levodopa treatment and were assessed in the “on” state (maximal efficacy). In this group, levodopa sensitivity was high (over 80%). In contrast, only five DLB patients (50%) were receiving levodopa, and pharmacological effects were limited (sensitivity <20%). PDD patients received levodopa and dopamine agonists more frequently than DBL patients (p<0.0001).

Treatment

There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients receiving cholinesterase inhibitors, anxiolytic, antidepressive or neuroleptic medications.

Neuropsychological findings (table 1)

Table 1 Neuropsychological data.

| Test (range) | DLB (n = 10) | PDD (n = 12) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mattis DRS (0–144) | 92 (21) | 102 (12) | NS |

| MMSE global score (0–30) | 16 (4) | 18 (4) | NS |

| Orientation subtest of MMSE (0–10) | 5 (2) | 7 (2) | <0.05 |

| Free and cued recall test (BSRT) | |||

| Free recall (0–48) | 7 (6) | 9 (8) | NS |

| Total recall (0–48) | 27 (10) | 34 (10) | NS |

| % sensitivity (0–100) | 50 (22) | 66 (21) | NS |

| WAIS‐R digit span subtest (direct) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | NS |

| WAIS‐R digit span subtest (reverse) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | NS |

| BVRT (0–15) | 5 (2) | 7 (3) | NS |

| DMS‐48 (immediate recognition) (0–48) | 28 (8) | 39 (5) | <0.05 |

| DMS‐48 (delayed recognition) (0–48) | 27 (7) | 36 (5) | <0.05 |

| ROCFT (memory) (0–36) | 3 (5) | 4 (6) | NS |

| DO‐80 (0–80) | 72 (6) | 74 (4) | NS |

| Letter fluency task 1 min (⩾0) | 3 (3) | 3 (1) | NS |

| Semantic fluency task 1 min (⩾0) | 8 (3) | 9 (3) | NS |

| BDAE comprehension (0–10) | 5 (2) | 6 (2) | NS |

| ROCFT (copy) (0–36) | 13 (14) | 16 (13) | NS |

| Poppelreuter (0–8) | 5 (1) | 6 (2) | NS |

| RCPMT (0–36) | 15 (8) | 15 (7) | NS |

| TMT A (time in s) | 260 (168) | 118 (52) | <0.05 |

| TMT B (time in s) | 404 (222) | 375 (203) | NS |

| Stroop reading of names of colours (T score) | 24.4 (5.4) | 32.7 (9.2) | <0.05 |

| Stroop recognition of colours (T score) | 23.8 (3.7) | 28.3 (7.8) | NS |

| Stroop conflictual task (T score) | 28 (8) | 32 (10.9) | NS |

| WCST criteria (0–20) | 4 (4) | 5 (3) | NS |

| FAB (0–18) | 8 (5) | 8 (4) | NS |

BDAE, Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination; BSRT, Buschke Selective Reminding Test; BVRT, Benton Visual Retention Test; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; DMS, Delayed Matching to Sample; DO, oral naming; FAB, Frontal Assessment Battery; Mattis DRS, Mattis Dementia Rating Scale; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; PDD, Parkinson's disease dementia; RCPMT, Raven Colour Progressive Matrix Test; ROCFT, Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test; TMT, Trail Making Test; WAIS‐R, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale‐Revised; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

Values are expressed as mean (SD).

The diagnostic groups were compared using the Wilcoxon test.

Differences between the two groups with regard to MMSE and Mattis Dementia Rating Scale scores were not statistically reliable at the 0.05 level.

We observed significant differences for orientation (p<0.05), Trail Making Test A (p<0.05), reading of names of colours on the Stroop Test (p<0.05), and immediate (p<0.05) and delayed (p<0.05) recognition on the DMS‐48 test (DLB patients consistently performed worse than PDD patients). All other comparisons were non‐significant.

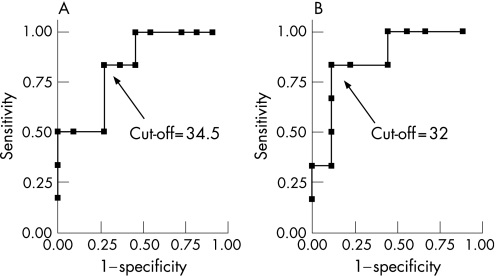

Receiver operator characteristic for DMS‐48 in the PDD group (fig 1)

Figure 1 Receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis of Delayed Matching to Sample (DMS)‐48 (A, immediate recognition) and DMS‐48 (B, delayed recognition) for predicting the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD) compared with that of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). The objective is to discriminate between DLB (cases) and PDD (non‐cases) using DMS‐48 scores (diagnostic test). ROC curves are graphical plots of the true positive rate (sensitivity) of diagnosing a DLB against the false positive rate (1−specificity) for the different possible cut‐off points of the diagnostic test. The best possible method for discriminating PDD from DLB would yield a curve going through the upper left corner of the ROC space (ie, 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity). A completely random predictor would give a straight line at an angle of 45° from the horizontal, from bottom left to top right. Results below this “no discrimination line” would suggest a detector that gave wrong results consistently, and could therefore be used simply to make a detector that gave useful results by inverting its decisions. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) gives a summary statistic quantifying how the diagnostic test discriminates between cases and non‐cases. It varies between 0.5 (the diagnostic test does not perform better than chance) and 1 (the diagnostic test allows perfect discrimination between cases and non‐cases). It can also be interpreted as the probability that when we randomly pick a patient with PDD and a patient with DLB, DMS‐48 will assign a smaller score to the DLB patient. In our example, for the DMS‐48 (immediate recognition) and the DMS‐48 (delayed recognition), AUC values were estimated at 0.83 and 0.87, respectively. Moreover, a DMS‐48 score (immediate recognition) of 34.5 is associated with a sensitivity of 83% (95% CI 35.9 to 99.6) and a specificity of 73% (95% CI 39.0 to 94.0) for the diagnosis of DLB compared with PDD. This results in a positive likelihood ratio of 3.1 (95% CI 1.1 to 8.6): a low DMS‐48 score (ie, smaller than 34.5) is observed 3.1 time more often in DLB patients than in PDD patients. Finally, a DMS‐48 score (delayed recognition) of 32 is associated with a sensitivity of 83% (95% CI 35.9 to 99.6) and a specificity of 89% (95% CI 51.8 to 99.7) for the diagnosis of DLB compared with PDD. This results in a positive likelihood ratio of 7.5 (95% CI 1.14 to 49.3): a low DMS‐48 score (ie, smaller than 32) is observed 7.5 times more often in DLB patients than in PDD patients.

The AUC values of the ROC curve for the DMS‐48 (immediate recognition) and the DMS‐48 (delayed recognition) were 0.83 and 0.87, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we compared the cognitive profiles in DLB and PDD patients using a broad neuropsychological battery. Most of the measures showed similar patterns globally, with a trend for poorer performance in the DLB group. These results are consistent with previous studies1,2,3 and suggest a common pathological process underlying the diseases.

However, despite the small sample size and large intragroup variability of results suggesting heterogeneous patterns, we observed some significant differences in cognitive patterns of DLB compared with PDD patients.

Firstly, patients in the DLB group had poorer performances in orientation subtests than PDD patients. As DLB is sometimes defined as a chronic confusional syndrome,23 this result is not surprising.

Secondly, performances were poorer in the DLB group in the Trail Making Test‐A test and in the reading of names of colours in the Stroop Test (ie, initial phases of each test). These results could suggest that DLB patients require more time than PDD patients to learn tasks, but once learned, tasks are performed to a similar standard by both groups.

The major result was the different pattern of memory impairment on the DMS‐48 test between PDD and DLB patients. This recently introduced test explores visual object recognition memory.24 Performances were more impaired in DLB patients (both in immediate and delayed recognition) than in the PDD group, suggesting the following hypotheses. As encoding is not controlled in the DMS‐48 test, DLB patients could have more severe attentional disturbances than PDD patients, resulting in less immediate recognition. Just as the immediate recognition score was low, delayed recognition was also impaired. We can also hypothesise that DLB patients have more functional alterations in temporal regions (in particular the perirhinal cortex that is crucial in visual object recognition memory).24

To our knowledge, ours is the first study describing differences in neuropsychological testing between PDD and DLB in terms of memory.

Few studies comparing cognitive functions in PDD and DLB have been published. Aarsland et al2 and Downes et al25 showed that executive functions in patients with mild DLB were more impaired than in patients with mild PDD. Ballard et al compared cognitive reaction times in several neurodegenerative pathologies but did not observe differences between PDD and DLB.1 Noe et al did not observe differences in memory using the Selective Reminding Test, or in a battery assessing a broad range of cognitive functions.3 Hence our study is the first to investigate DMS‐48 in DLB and PDD.

Our findings must be consolidated in future studies, with a larger sample of patients. Nevertheless, based on our results, neuropsychological testing, especially DMS‐48, appears to be useful in characterising DLB and PDD.

Abbreviations

DLB - dementia with Lewy bodies

DMS - Delayed Matching to Sample

MMSE - Mini‐Mental State Examination

PDD - Parkinson's disease dementia

ROC - receiver operator characteristic

UPDRS - Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Received 10 August 2006

References

- 1.Ballard C G, Aarsland D, McKeith I.et al Fluctuations in attention: PD dementia vs DLB with parkinsonism. Neurology 2002591714–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aarsland D, Litvan I, Salmon D.et al Performance on the dementia rating scale in Parkinson's disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies: comparison with progressive supranuclear palsy and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003741215–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noe E, Marder K, Bell K L.et al Comparison of dementia with Lewy bodies to Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease with dementia. Mov Disord 20041960–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKeith I G, Dickson D W, Lowe J.et al Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2005651863–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes A J, Daniel S E, Kilford L.et al Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a clinico‐pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 199255181–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawton M P, Brody E M. Assessment of older people: self‐maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 19699179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folstein M F, Folstein S E, McHugh P R. “Mini‐mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 197512189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grober E, Buschke H, Crystal H.et al Screening for dementia by memory testing. Neurology 198838900–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wechsler D A.Echelle d'intelligence de Wechsler pour adultes forme révisée WAIS‐R. Manuel. Paris: Centre de Psychologie Appliquée, 1989

- 10.Benton A L. Test de rétention Visuelle, édition française. In: Editions du Centre de Psychologie Appliquée, ed. Paris 1982

- 11.Barbeau E, Tramoni E, Joubert S.et al Evaluation de la mémoire de reconnaissance visuelle: normalisation d'une nouvelle épreuve en choix forcé (DMS48) et utilité en neuropsychologie clinique. In: Van Der Linden M et les membres du Gremem, ed. L'évaluation des troubles de la mémoire. Marseille: Solal, 200485–101.

- 12.Rey A. Test de copie et production d'une figure complexe. In: Editions du Centre de Psychologie Appliquée, ed. Paris 1959

- 13.Deloche G, Metz‐Lutz M, Kremin H. Test de dénomination orale de 80 images: DO 80. In: Editions du Centre de Psychologie Appliquée CDP, ed. Paris 1997

- 14.Cardebat D, Doyon B, Puel M.et al Formal and semantic lexical evocation in normal subjects. Performance and dynamics of production as a function of sex, age and educational level. Acta Neurol Belg 199090207–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazaux J M, Orgozozo J M. Echelle d'évaluation de l'aphasie adaptée du Boston. Diagnostic Aphasia Examination de Goodglass H. et Kaplan E. In: Editions scientifiques et psychotechniques, ed. Paris, 1981

- 16.Poppelreuter W. Die Psychischen Schadigungen durch Kopfschuss im Kriege 1914/16. In: Voss L, ed. Leipzig 1917

- 17.Raven J‐ C. Coloured progressive matrices, Sets A, Ab, B. In: H K Lewis and co, eds. London 1956

- 18.Reitan R M. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indication of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills 19588271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stroop J. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol 193518643–662. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson H E. A modified card sorting test sensitive to frontal lobe defects. Cortex 197612313–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I.et al The FAB: a Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside. Neurology 2000551621–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metz C E, Goodenough D J, Rossmann K. Evaluation of receiver operating characteristic curve data in terms of information theory, with applications in radiography. Radiology 1973109297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballard C, O'Brien J, Gray A.et al Attention and fluctuating attention in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 200158977–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barbeau E, Didic M, Tramoni E.et al Evaluation of visual recognition memory in MCI patients. Neurology 2004621317–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Downes J J, Priestley N M, Doran M.et al Intellectual, mnemonic, and frontal functions in dementia with Lewy bodies: A comparison with early and advanced Parkinson's disease. Behav Neurol 199811173–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]