We report a presentation of relapsing and remitting isolated intracranial neurosarcoidosis in a female patient who presented with episodic severe headache and behavioural disturbance initially misdiagnosed as psychosis. Eventually, several episodes were accompanied by visual disturbance secondary to papilloedema, ultimately leading to a diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis on meningeal biopsy.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease of unknown aetiology, and is characterised by non‐caseating granulomata. Pulmonary disease is the most common manifestation, occurring in 90% of patients. Clinical involvement of the nervous system is said to occur in 5–15% of patients.1 Isolated intracranial neurosarcoidosis is even rarer, with systemic sarcoidosis being detected in more than 95% of cases of sarcoidosis initially presenting with neurological symptoms.2

Case report

A woman presented initially at age 30 years, and then subsequently five times over 3 years with stereotyped episodes of headache, confusion and psychomotor agitation. In each instance, a history was given of a constant, severe bifrontal headache that was associated with nausea, vomiting, photophobia and/or visual field disturbance. As each presentation evolved, she became confused and encephalopathic. Early in the course of her illness these episodes were misinterpreted as acute psychosis because she exhibited pressured unintelligible speech, and was combative and sometimes frankly violent. However, although disoriented and confused, there were no features of a formal thought disorder. The accompanying headache was exacerbated by sneezing, coughing and the Valsalva manoeuvre. Treatment with analgesia and sumatriptan provided only limited relief as did prophylaxis with beta blockers. There was no history of a previous psychiatric disorder or substance abuse. The patient did have a long past history of migrainous headaches that were typically unifrontal, mild and managed adequately with simple analgesics. Systemic review revealed no respiratory or dermatological complaint.

On examination she was consistently afebrile. There was no neck stiffness or rash. Transient visual field loss (bitemporal or subtotal loss of vision) was noted during later episodes; visual acuity was well preserved. Retinal examination showed papilloedema, perivenular inflammation and absence of venous pulsations.

Plain chest x rays were unremarkable during each of her five presentations. Cranial MRI with contrast, MR angiography and MR venography were all initially normal. Serial CSF analysis showed lymphocytic pleocytosis, suggestive of an encephalitis, only during her initial admission (57 cells/μl), but consistently elevated protein (0.90, 0.63 and 0.83 g/l) and normal glucose. Lumbar puncture opening pressures were raised (32 cm H2O) when symptomatic, but normal (16.5 mmH2O) 5 months later during a period of remission. Viral PCR studies for enterovirus, Murray valley encephalitis, herpes simplex and herpes zoster, and bacterial and fungal microscopy and cultures were negative. Oligoclonal bands were not present in the CSF. Angiotensin converting enzyme was not elevated in the blood or CSF. Results were within normal limits for all remaining laboratory tests, including autoimmune screens.

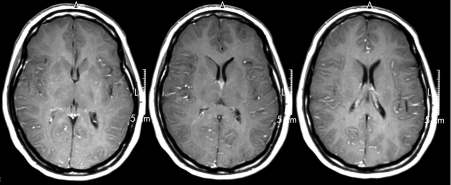

On her fourth admission, cranial MRI demonstrated subtle meningeal enhancement seen with contrast (fig 1). Subsequent open meningeal biopsy showed abundant non‐necrotising epithelioid granulomas localised to the arachnoid, consistent with granulomatous leptomeningitis. There was no evidence of acid‐fast bacilli or fungal organisms or the presence of significant fibrotic or vasculitic change. The cerebral cortex and dura were histologically normal. A diagnosis was made of isolated neurosarcoidosis.

Figure 1 Cranial MRI: T1 sequences with gadolinium contrast showing subtle but widespread cerebral leptomeningeal enhancement without thickening or nodularity.

The patient was commenced on oral prednisolone 75 mg daily. There was an excellent and sustained response to corticosteriods and, with the addition of hydroxychloroquine, the dose of prednisolone could be tapered to 16 mg on alternate days. Prednisolone doses were episodically increased to control symptoms. During the last 36 months of follow‐up she has been headache‐free and has had no further episodes of encephalitis or encephalopathy. Her papilloedema has largely resolved and a follow‐up CSF sample 10 months after treatment commenced was acellular (neutrophils 0 cells/μl, lymphocytes 0 cells/μl) with normal protein (0.3 g/l) and opening pressure.

Discussion

Neurosarcoidosis without pulmonary or other extracranial involvement can be a diagnostic challenge. The clinical features are protean. After cranial neuropathy, headache is the most common manifestation of neurosarcoidosis, affecting an estimated 30% of patients.2 There is no typical headache although reports suggest leptomeningeal inflammation is often associated with diffuse or bifrontal pain, and may be associated with papilloedema, as noted in this case.3 CSF analysis can be helpful when a pattern of mild pleocytosis, high protein content and, sometimes, reduced glucose is seen. However, CSF abnormalities are not specific to the disease, may be evanescent and in more than a third of cases patients have a normal CSF.1 Cranial MRI is the most valuable investigative tool with CNS lesions present in 80–90% of affected patients.4 In our case the MRI findings suggestive of leptomeningeal inflammation were made 3 years after the first admission, following previously normal cranial magnetic resonance imaging studies. Alternative diagnoses such as hypertrophic pachymeningitis were considered but the meningeal biopsy showing abundant non‐caseating epitheliod granulomas in the absence of fibrosis allowed the definitive diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis.

Neurosarcoidosis has been associated with neuropsychiatric dysfunction, including dementia, amnesia, depression, delirium and psychosis.1 In our patient, however, the episodic relapsing remitting course of headache, meningoencephalitis and papilloedema was unique. Furthermore, over 3 years of follow‐up there have been no emerging signs of extracranial sarcoidosis. The presentation is reminiscent of headache with neurological deficits and cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytosis (HaNDL) a disorder of unknown aetiology but with a benign course.5 It is possible that neurosarcoidosis is the cause of some cases of HaNDL.

Isolated neurosarcoidosis is a differential diagnosis that requires consideration in a patient presenting with otherwise unexplained headache and encephalopathy, even if it is relapsing. Our case has demonstrated that this diagnosis may require considerable persistence with repetition of previous normal diagnostic and imaging investigations.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Hoitsma E, Faber C G, Drent M.et al Neurosarcoidosis: a clinical dilemma. Lancet Neurol 20043397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nowak D A, Widenka D C. Neurosarcoidosis: a review of its intracranial manifestation. J Neurol 2001248363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vannemreddy P S, Nanda A, Reddy P K.et al Primary cerebral sarcoid granuloma: the importance of definitive diagnosis in the high‐risk patient population. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2002104289–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christoforidis G A, Spickler E M, Recio M V.et al MR of CNS sarcoidosis: correlation of imaging features to clinical symptoms and response to treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 199920655–669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman K M, Szczygielski B I, Toth C.et al Pseudomigraine with lymphocytic pleocytosis: a calcium channelopathy? Clinical description of 10 cases and genetic analysis of the familial hemiplegic migraine gene CACNA1A. Headache 200343892–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]