Abstract

Background

While some regard the flail arm syndrome as a variant of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), others have argued that it is a distinct clinical entity. Consequently, the present study applied novel central and peripheral nerve excitability techniques to further explore disease pathophysiology in flail arm syndrome.

Methods

Cortical and peripheral nerve excitability studies were undertaken in 11 flail arm patients, defined by muscle weakness limited to the proximal aspects of the upper limbs for at least 24 months.

Results

Mean age at disease onset (60.3 years) was similar to other ALS phenotypes (58.3 years), with strong male predominance (male:female distribution: flail arm 10:1; ALS 1.5:1; p<0.05) and prolonged disease duration (flail arm 62.5 months; ALS 15.8 months; p<0.05). There was evidence of cortical hyperexcitability in flail arm patients, similar to findings in ALS, with reduction in short interval intracortical inhibition (flail arm 0.8 (0.6)%; ALS 4.1 (1.1)%; controls 8.5 (1.0)%; p<0.0001) and resting motor threshold (flail arm 53.4 (2.8)%; ALS 56.6 (1.8)%; controls 60.7 (1.5)%; p<0.05), along with an increase in motor evoked potential amplitude (flail arm 49.5 (9.0)%; ALS 44.4 (4.9)%; controls 25.8 (2.8)%; p<0.05). Peripheral nerve excitability studies demonstrated changes consistent with upregulation in persistent Na+ currents and reduction of slow K+ conductances, similar to findings in ALS.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated the presence of cortical hyperexcitability in flail arm syndrome, along with abnormalities in peripheral nerve excitability, findings consistent with previous studies in other ALS phenotypes. By demonstrating the presence of upper motor neuron dysfunction, the present study suggests that the flail arm syndrome is an unusual variant of ALS.

The “man‐in‐the barrel” syndrome is clinically characterised by severe bilateral weakness of the shoulder girdle musculature, originally reported in the setting of cerebral infarction.1 A neurogenic variant of “man‐in‐the barrel” syndrome resulting from cervical anterior horn cell loss has been reported.2,3 While the “man‐in‐the barrel” syndrome was first described by Vulpian,4 and elegantly illustrated by Gowers,5 later studies by Hu and colleagues2 reaffirmed the original observations that this phenotype was a variant of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Others have argued that the neurogenic “man‐in‐the‐barrel” syndrome represents a entity distinct from ALS (brachial amyotrophic diplegia3). Indeed, the flail arm syndrome or “brachial amyotrophic diplegia” may be clinically differentiated from classic ALS by the unique pattern of muscle weakness, absence of upper motor neuron signs in the affected upper limbs and prolonged survival.2,3

The diagnosis of ALS relies on the presence of a combination of upper and lower motor neuron features with evidence of disease progression over time.6 Clinical evidence of upper motor neuron (UMN) dysfunction may be elusive,7 particularly in the early stages of ALS, or when UMN dysfunction becomes obscured by severe motor neuron loss. Given the uncertainties of the neurogenic “man‐in‐the‐barrel” syndrome, the aim of the present study was to implement novel cortical threshold tracking transcranial magnetic stimulation techniques to further explore disease pathophysiology compared with more typical ALS phenotypes.

Patients and methods

Patients

Eleven patients were studied with the flail arm syndrome, defined as the presence of progressive weakness limited to the proximal aspects of the upper limbs for a period of 24 months, with neurophysiological evidence of lower motor neuron dysfunction. All patients were staged using the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale‐Revised (ALSFRS‐R),8 Medical Research Council rating scale9 and an UMN score10 after informed consent was obtained.

Cortical excitability

Cortical excitability was measured by applying transcranial magnetic stimulation to the motor cortex by means of a 90 mm circular coil. A threshold tracking paradigm was applied to record the stimulus response curves, short interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) and central motor conduction time, as previously described.11 Peripheral nerve excitability studies were also undertaken in the same sitting,12 with the median nerve stimulated at the wrist using 5 mm Ag‐AgCl electrodes. The resultant compound muscle action potential (CMAP) was recorded using surface electrodes positioned over the abductor pollicis brevis and measured from baseline to negative peak. The Neurophysiological Index was also derived.13

Cortical and peripheral nerve excitability in flail arm patients was compared with other ALS phenotypes (n = 26)14 and previously published normative data.11 The Student's t test was used to compare differences between groups with analysis of variance for multiple comparisons. Results are expressed as mean (SEM).

Results

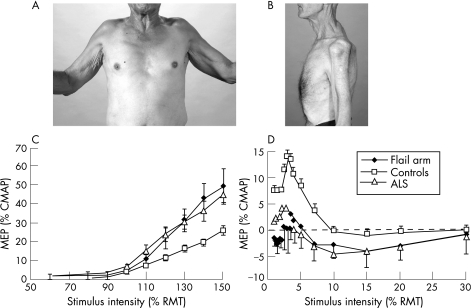

Two typical patients with the flail arm syndrome are illustrated in fig 1A and 1B and the clinical features of all 11 flail arm patients are summarised in table 1. Mean age at disease onset was similar for flail arm patients and other ALS phenotypes (flail arm 60.3 (3.0) years; other ALS phenotypes 58.3 (1.8) years). There was a significant male predominance in the flail arm patients compared with the other ALS phenotypes (flail arm 10:1; other ALS phenotypes 1.5:1; p<0.05), and the mean duration of illness was significantly longer (flail arm 62.5 (15.6) months; other ALS phenotypes 15.8 (2.3) months; p<0.05).

Figure 1 (A) Anterior view (patient No 5) and (B) lateral view (patient No 4) of two patients from the present series with flail arm syndrome attempting shoulder abduction. There is marked wasting of the anterior and posterior shoulder girdle muscles, with an inability to abduct the shoulders, with a resultant “man‐in‐the‐barrel” syndrome. (C) Stimulus–response curves obtained following transcranial magnetic stimulation stimulation in 8 flail arm patients, 26 patients with other amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) phenotypes and 39 normal controls. The motor evoked potential (MEP) is expressed as a percentage of the compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitude, recorded following electrical stimulation. The MEP amplitude was significantly increased in flail arm and other ALS patients compared with controls over stimulus intensities from 110 to 150% (p<0.05) of resting motor threshold (RMT). (D) Short interval intracortical inhibition, defined as the stimulus intensity required to maintain a target output of 0.2 mV, was reduced in both flail arm (n = 8, p<0.0001) and other ALS patients (n = 26, p<0.001) compared with controls. Informed consent was obtained for publication of this figure.

Table 1 Clinical details for the 11 patients with flail arm syndrome.

| Patient No | Age (y)/sex | Disease duration (months) | ALSFRS‐R | Triggs hand score | MRC UL proximal score | MRC UL distal score | UMN score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1†*‡ | 59, M | 57 | 30 | 2 | 24 | 38 | 0 |

| 2*‡ | 50, M | 24 | 42 | 0 | 40 | 60 | 6 |

| 3*‡ | 71, M | 96 | 38 | 0 | 40 | 52 | 0 |

| 4†*‡ | 67, M | 48 | 40 | 2 | 48 | 46 | 0 |

| 5*‡ | 69, M | 10 | 42 | 2 | 40 | 40 | 6 |

| 6* | 52, M | 180 | 44 | 1 | 40 | 48 | 0 |

| 7*‡ | 68, M | 74 | 15 | 2 | 36 | 36 | 0 |

| 8 | 73, M | 24 | 32 | 2 | 24 | 42 | 6 |

| 9† | 67, F | 96 | 28 | 2 | 36 | 38 | 0 |

| 10*‡ | 42, M | 31 | 46 | 0 | 30 | 58 | 0 |

| 11*‡ | 56, M | 36 | 40 | 2 | 46 | 60 | 6 |

| Mean | 61.3 | 61.5 | 36.1 | 1.4 | 36.7 | 47.1 | 2.2 |

| SEM | 3.7 | 14.7 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 0.9 |

ALSFRS‐R, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale‐Revised; MRC, Medical Research Council; UL, upper limbs; UMN, upper motor neuron.

†Deceased patients.

Patients with flail arm syndrome had increased survival, with 8 of the 11 patients from the present series still being alive.

Mean age refers to patient age at the time of examination.

Cortical excitability was undertaken in 8 flail arm patients (*), while peripheral nerve excitability was completed in 9 flail arm patients (‡).

Disease duration refers to the period from symptom onset to the date of testing or last review in the ALS clinic.

Patients were clinically graded using the ALSFRS‐R, with a maximum score of 48 when there is no disability.

Muscle strength in the proximal upper limbs was graded by summating the MRC score for 12 different movements (ie, shoulder abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation, and elbow flexion and extension bilaterally) for a maximum score of 60, while strength in the distal upper limbs was also assessed for 12 different movements (ie, wrist flexion and extension, finger and thumb abduction, finger extension and flexion bilaterally) for a maximum score of 60.

The UMN score comprised a sum of pathologically brisk reflexes that included the assessment of biceps, supinator, triceps, finger, knee and ankle reflexes, with plantar responses, facial and jaw jerks, all bilaterally, for a maximum possible score of 16. UMN involvement was graded according to the UMN score, with a maximum score of 16. Four patients were graded as having a UMN score of 6 because of hyperreflexia in the lower limbs. Patient No 11 had longstanding hyperreflexia due to a prior closed head injury at age 7 years.

Although muscle weakness was initially confined to the proximal upper limbs, lower limb symptoms, including fasciculations, muscle wasting and bilateral foot drop, developed in 18% of patients, on average 58.8 months after symptom onset. Bulbar symptoms, including dysarthria, tongue weakness and dysphagia, developed in 27% of patients, and respiratory symptoms occurred in 18% of patients, with these patients subsequently requiring ongoing non‐invasive ventilatory support.

Cortical excitability was assessed in eight flail arm patients, on average 47 months after symptom onset (range 31–96 months), and the mean ALSFRS‐R score at the time of testing was 38 (range 15–46). Central motor conduction time was not significantly different compared with ALS patients or normal controls (flail arm 5.9 (0.4) ms; ALS 5.1 (0.5) ms; controls 5.1 (0.3) ms).

Resting motor threshold in flail arm patients was similar to other ALS phenotypes but was significantly reduced compared with controls (flail arm 53.4 (2.8)%; ALS 56.6 (1.8)%; controls 60.7 (1.5)%; p<0.05). MEP amplitude, expressed as a percentage of CMAP amplitude, was increased in flail arm patients compared with normal controls (p<0.05) (fig 1C), but was similar to ALS patients (p = 0.3) (fig 1C).

SICI was significantly reduced in both flail arm (averaged SICI from 1 to 7 ms, −0.8 (0.6)%; p<0.0001) and other ALS phenotypes (4.1 (1.1)%; p<0.01) compared with normal controls (8.5 (1.1)%; p<0.0001) (fig 1D). After SICI, a period of intracortical facilitation followed, and was significantly increased in flail arm patients compared with controls (p<0.05) (fig 1D).

Peripheral nerve excitability studies were undertaken in nine flail arm patients. Stimulus–response curves were shifted to the right in the flail arm patients and other ALS phenotypes for stimuli of both 0.2 and 1 ms duration, indicating that axons were of higher threshold relative to controls. CMAP amplitude (flail arm 2.0 (1.6) mV; ALS 2.6 (1.2) mV; controls 9.8 (0.5) mV; p<0.001) and Neurophysiological Index (flail arm 0.5 (0.1); ALS 0.8 (0.1); controls 2.5 (0.1); p<0.0001) were significantly reduced in flail arm and other ALS phenotypes compared with controls.

Strength–duration time constant reflects nodal persistent Na+ conductance, while rheobase is defined as the threshold current for a stimulus of infinitely long duration.15 As previously established in ALS,16 the mean τSD was longer in flail arm patients compared with controls (flail arm 0.45 (0.05) ms; ALS 0.49 (0.03) ms; controls 0.41 (0.02) ms) and rheobase was increased (flail arm 3.5 (1.2) mA; ALS 3.3 (1.1) mA; controls 3.1 (1.1) mA; p = 0.5).

The type I abnormality of threshold electrotonus, which reflects a greater change in response to a sub‐threshold depolarising pulse, has been reported previously in ALS.17 Mean data in flail arm patients revealed the presence of this type I abnormality (flail arm 49.6 (2.2); ALS 49.8 (1.4); controls 45.6 (0.7); p<0.05). There was no significant change in any of the parameters of the recovery cycle or current–threshold relationship in flail arm patients.

Discussion

The present study has further defined the flail arm phenotype, which is clinically characterised by proximal upper limb weakness, male predominance and prolonged survival. Despite the absence of upper motor neuron features (increased tone, hyperreflexia and extensor plantar responses), the present study has established the presence of cortical hyperexcitability, as indicated by reduction in resting motor threshold and short interval intracortical inhibition, together with increases in MEP amplitude and cortical stimulus–response curve gradient in flail arm patients. Changes in cortical excitability were accompanied by abnormalities of peripheral axonal excitability, including an increase in persistent Na+ conductances and reduction in slow K+ conductances. Taken together, these changes in cortical and peripheral excitability are in keeping with findings in ALS, and provide supportive evidence that the flail arm syndrome is indeed a variant of ALS.

Prior to considering the diagnosis of flail arm variant of ALS, a number of secondary disorders that can result in the same clinical phenotype need to be excluded. Cortical,1 pontine18 and spinal cord lesions,19 along with demyelinating neuropathies, are important differential diagnoses that may mimic the flail arm syndrome.20 All of these conditions were excluded in the present study on the basis of clinical investigations, including imaging of the brain and cervical spine, neurophysiological studies and laboratory testing.

The present study has provided evidence for UMN dysfunction in flail arm patients by establishing a significant reduction in SICI. SICI is believed to be cortical in origin, mediated by GABA secreting inhibitory cortical interneurons via GABAA receptors.21 Loss of these inhibitory cortical interneurons partly accounts for the reduction in SICI in flail arm syndrome, as previously established in ALS.22 By demonstrating the presence of UMN dysfunction in the setting of clinical disease progression, the present study suggests that the flail arm syndrome is an unusual variant of ALS.

Given that neurophysiological studies have revealed similar abnormalities of cortical and axonal excitability between flail arm and ALS patients, it remains unclear what underlies the differences between the clinical phenotype. The greater male predominance in flail arm patients may suggest an influence of hormonal factors. In the central nervous system, expression of the androgen receptor is relatively high in spinal motor neurons.23 Studies investigating the function of the androgen receptor and its agonists, such as testosterone, may yet prove useful in unlocking this clinical mystery.

Acknowledgements

SV was awarded the Clinical Fellowship of the Motor Neurone Disease Research Institute of Australia (MNDRIA), with funding provided by the Motor Neuron Disease Association of NSW. Grant support was also received from the NSW Ministry for Science and Medical Research Spinal Cord Injury and Related Neurological Conditions Research Grant Program. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Con Yiannikas for helpful discussion.

Abbreviations

ALS - amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

ALSFRS‐R - Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale‐Revised

CMAP - compound muscle action potential

MEP - motor evoked potential

SICI - short interval intracortical inhibition

UMN - upper motor neuron

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

This study was presented in part at the 18th World Congress of Neurology, Australia and the 16th International Symposium on ALS/MND, Republic of Ireland.

Informed consent was obtained for publication of fig 1.

References

- 1.Sage J I, Van Uitert R L. Man‐in‐the‐barrel syndrome. Neurology 1986361102–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu M T, Ellis C M, Al‐Chalabi A.et al Flail arm syndrome: a distinctive variant of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 199865950–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz J S, Wolfe G I, Andersson P B.et al Brachial amyotrophic diplegia: a slowly progressive motor neuron disorder. Neurology 1999531071–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vulpian A.Maladies du système nerveux (moelle épinière), vol 2. Paris: Octave Doin, 1886

- 5.Gowers W. A Manual of diseases of the nervous system: spinal cord and nerves. London: Churchill, 1888

- 6.Kiernan M C. Motor neurone disease: a Pandora's box. Med J Aust 2003178311–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Triggs W J, Menkes D, Onorato J.et al Transcranial magnetic stimulation identifies upper motor neuron involvement in motor neuron disease. Neurology 199953605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cedarbaum J M, Stambler N, Malta E.et al The ALSFRS‐R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. BDNF ALS Study Group (Phase III). J Neurol Sci 199916913–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medical Reserach Council Aid to the examination of the peripheral nervous system. London: Her Majesty's Stationary Office, 1976

- 10.Turner M R, Cagnin A, Turkheimer F E.et al Evidence of widespread cerebral microglial activation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an [11C](R)‐PK11195 positron emission tomography study. Neurobiol Dis 200415601–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vucic S, Howells J, Trevillion L.et al Assessment of cortical excitability using threshold tracking techniques. Muscle Nerve 200633477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiernan M C, Burke D, Andersen K V.et al Multiple measures of axonal excitability: a new approach in clinical testing. Muscle Nerve 200023399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Carvalho M, Swash M. Nerve conduction studies in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 200023344–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vucic S, Kiernan M C. Novel threshold tracking techniques suggest that cortical hyperexcitability is an early feature of MND. Brain 20061292436–2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bostock H. The strength–duration relationship for excitation of myelinated nerve: computed dependence on membrane parameters. J Physiol (Lond) 198334159–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mogyoros I, Kiernan M C, Burke D.et al Strength–duration properties of sensory and motor axons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 1998121851–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bostock H, Sharief M K, Reid G.et al Axonal ion channel dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 1995118217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulin M, de Seze J, Wyremblewski P.et al Man‐in‐the‐barrel syndrome caused by a pontine lesion. Neurology 2005641703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kameyama T, Ando T, Yanagi T.et al Cervical spondylotic amyotrophy. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstration of intrinsic cord pathology. Spine 199823448–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parry G J, Clarke S. Multifocal acquired demyelinating neuropathy masquerading as motor neuron disease. Muscle Nerve 198811103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziemann U. TMS and drugs. Clin Neurophysiol 20041151717–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nihei K, McKee A C, Kowall N W. Patterns of neuronal degeneration in the motor cortex of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Acta Neuropathol 19938655–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katsuno M, Adachi H, Waza M.et al Pathogenesis, animal models and therapeutics in Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA). Exp Neurol 200688–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]