Abstract

Background

Eosinophilic vasculitis has been described as part of the Churg–Strauss syndrome, but affects the central nervous system (CNS) in <10% of cases; presentation in an isolated CNS distribution is rare. We present a case of eosinophilic vasculitis isolated to the CNS.

Case report

A 39‐year‐old woman with a history of migraine without aura presented to an institution (located in the borough of Queens, New York, USA; no academic affiliation) in an acute confusional state with concurrent headache and left‐sided weakness and numbness. Laboratory evaluation showed increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein level, but an otherwise unremarkable serological investigation. Magnetic resonance imaging showed bifrontal polar gyral‐enhancing brain lesions. Her symptoms resolved over 2 weeks without residual deficit. After 18 months, later the patient presented with similar symptoms and neuroradiological findings involving territories different from those in her first episode. Again, the CSF protein level was high. She had a raised C reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Brain biopsy showed transmural, predominantly eosinophilic, inflammatory infiltrates of medium‐sized leptomeningeal arteries without granulomas. She improved, without recurrence, when treated with a prolonged course of corticosteroids.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first case of non‐granulomatous eosinophilic vasculitis isolated to the CNS. No aetiology for this patient's primary CNS eosinophilic vasculitis has yet been identified. Spontaneous resolution and recurrence of her syndrome is an unusual feature of the typical CNS vasculitis and may suggest an environmental epitope with immune reaction as the cause.

Eosinophilic vasculitis has been described as part of the Churg–Strauss syndrome, but affects the central nervous system (CNS) in only 6–7% of cases.1,2 Presentation in an isolated CNS distribution is rare. We present a case of eosinophilic vasculitis isolated to the CNS.

Case report

A 39‐year‐old woman with a history of migraine without aura presented to an institution (located in the borough of Queens, New York, USA; no academic affiliation) in an acute confusional state with concurrent headache and left‐sided weakness and numbness. A lumbar puncture showed acellular cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with a slightly increased protein concentration. She was treated presumptively for herpes encephalitis on the basis of an increased herpes simplex virus (HSV)‐2 IgG titre in the serum and CSF (IgM not analysed and CSF polymerase chain reaction negative), as well as bifrontal polar gyral‐enhancing brain lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Her symptoms resolved over 2 weeks without residual deficit. After 18 months, the patient presented again with a similar constellation of symptoms, including acute‐onset headache, confusion, left visual field flashes, and left‐sided numbness and weakness. An MRI showed new occipital–parietal leptomeningeal‐enhancing lesions; lumbar puncture again showed acellular CSF with raised protein concentration (128 mg/dl). She was transferred to The Neurological Institute of New York for further management.

The patient worked at a perfume counter and identified odours of certain perfumes as a trigger for her migraine attacks. She had no respiratory complaints including asthma, rash, constitutional symptoms or allergies. Other than a multivitamin, she took no drugs regularly, including non‐prescription supplements. Further history and physical examination showed no features suggestive of systemic vasculitis, including lymphadenopathy or rash. Neurological examination was notable for mildly impaired attention, a left homonymous lower quadrantanopsia, left hemiparesis and left patchy hemihypesthesia.

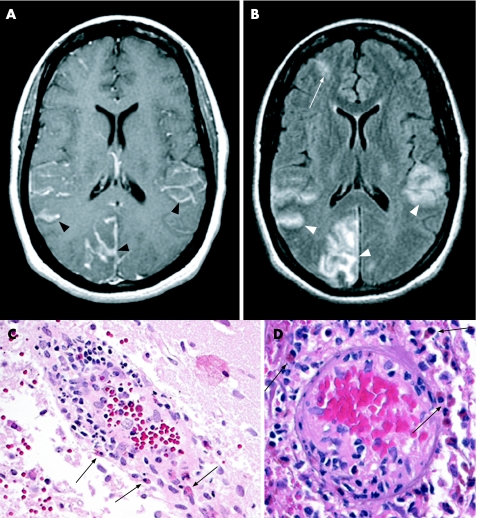

Brain MRI showed right occipital, anterior frontal and bilateral parietal cortical lesions with leptomeningeal enhancement on the T1‐weighted post‐contrast images (fig1A, black arrowheads). Gradient echo showed patchy low signal in sulci, consistent with persistent intracellular deoxyhaemoglobin or methaemoglobin. FLAIR images showed high signal of the cortical mantle as well as the subarachnoid space in the adjacent gyri (fig1B, white arrowheads) that showed prolonged diffusion rates on diffusion‐weighted images and apparent diffusion coefficient maps, consistent with inflammatory oedema or subacute ischaemia. The bifrontal lesions observed on MRI during the patient's previous hospitalisation were faintly visible on the FLAIR sequence (fig1B, white arrow) and showed low signal in the sulci on the gradient echo images, consistent with haemosiderin deposition from a prior haemorrhage.

Serum inflammatory markers were increased, with erythrocyte sedimentation rate 35 mm/h (normal range 0–22 mm/h) and C reactive protein level 92.6 mg/l (normal <3 mg/l; table 1). The patient had a normal blood count including only 1% eosinophils. Serum electrolytes, creatinine, liver enzymes and urine analysis were also normal. Antithyroglobulin and antimicrosomal antibodies were not detected. Stool was negative for ova and parasites. CSF examination showed 2 leucocytes/mm3 (100% lymphocytes), 300 erythrocytes/mm3, a protein level of 119 mg/dl and normal glucose. CSF cultures were negative, as were polymerase chain reaction studies for HSV‐1 and HSV‐2 and varicella zoster virus. Serum rapid plasma reagin was non‐reactive and the patient was HIV negative. Rheumatological studies, including antinuclear antibodies, anti‐DNA, anti‐extractable nuclear antigens, antineutrophil cytoplasmic (cANCA, pANCA), rheumatoid factor and lupus anticoagulant, were negative. A DNA analysis was carried out to look for mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke‐like episodes (MELAS), but there was no A3243G mutation. Cerebral angiography showed no evidence of focal arterial narrowing. Computed axial tomography of the chest was normal.

Table 1 Laboratory studies on the patient.

| Prior illness (outside hospital, 1 year earlier) | Current illness | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2 (outside hospital) | D4 (presentation to our institution) | D5 | D9 | Reference range | ||

| Blood | ||||||

| WBC | 5.7 | 3.54–9.06×109/l | ||||

| Hgb | 12.2 | 12.0–15.8 g/dl | ||||

| MCV | 92.8 | 79–93.3 fl | ||||

| Plt | 168 | 165–415 | ||||

| Lymphocytes | 11 | 20–50% | ||||

| Neutrophils | 80 | 40–70% | ||||

| Monocytes | 8 | 4–8% | ||||

| Eosinophils | 1 | 0–6% | ||||

| Basophils | 0 | 0–2% | ||||

| Na | 139 | 136–146 mM/l | ||||

| K | 4.1 | 3.6–5.0 mM/l | ||||

| Cl | 109 | 102–109 mM/l | ||||

| CO2 | 20 | 25–33 mM/l | ||||

| BUN | 11 | 7–20 mg/dl | ||||

| Cr | 1.3 | 0.5–0.9 mg/dl | ||||

| Glucose | 119 | 79–105 mg/dl | ||||

| Ca | 8.5 | 8.4–9.8 mg/dl | ||||

| P | 2.9 | 2.5–4.3 mg/dl | ||||

| Mg | 1.9 | 1.5–2.3 mg/dl | ||||

| CK | 168 | 39–238 U/l | ||||

| Total protein | 6.4 | 6.7–8.6 g/dl | ||||

| Albumin | 3.7 | 4.0–5.0 g/dl | ||||

| Total bilirubin | 0.4 | 0.30–1.30 mg/dl | ||||

| Direct bilirubin | 0.1 | 0.04–0.38 mg/dl | ||||

| AST | 19 | 12–38 U/l | ||||

| ALT | 10 | 7–41 U/l | ||||

| Alkaline phosphatase | 45 | 33–96 U/l | ||||

| TSH | 8.06 | 0.34–4.25 μU/ml | ||||

| T4 | 7.13 | 5.41–11.66 μg/dl | ||||

| Free T4 | 1.0 | 0.8–1.8 ng/dl | ||||

| T3 | 58 | 76.91–134.74 ng/dl | ||||

| ESR | 48 | 35 | 0–20 mm/h | |||

| CRP | 92.6 | <3 mg/l | ||||

| Homocysteine | 5.3 | 4.4–10.8 μmol/l | ||||

| B12 | 346 | 279–996 pg/ml | ||||

| Arterial lactate | 1.1 | 0.50–1.60 mM/l | ||||

| RF | <9.5 | <15 | ||||

| RPR | NR | |||||

| ANA | Negative | |||||

| Angiotensin‐converting enzyme | 26 | 9–67 U/l | ||||

| Anti‐DNA Ab | 12 | <25 IU/ml negative | ||||

| Anti‐ENA (includes anti‐SS‐A/Ro, SS‐B/La, SM, U1RNP, SCL‐70, and Jo‐1 | 2.0 | 0.0–19.9 negative | ||||

| P‐ANCA | 0 | <6 | ||||

| C‐ANCA | 0 | <2 | ||||

| Anti‐cardiolipin Ab (IgG and IgM) | Negative | |||||

| C3 | 111 | 83–177 mg/dl | ||||

| C4 | 31 | 16–47 mg/dl | ||||

| CH50 | 194 | 50–150% | ||||

| Quantitative IgA | 239 | 70–350 mg/dl | ||||

| Quantitative IgG | 1120 | 700–1700 mg/dl | ||||

| Quantitative IgM | 180 | 50–300 mg/dl | ||||

| Antithyroglobulin antibody | Negative | |||||

| Antimicrosomal antibody | Negative | |||||

| HIV‐1 and HIV‐2 ELISA | Negative | Negative | ||||

| CMV IgM | 0.11 | >0.90 positive | ||||

| EBV IgG | 5.42 | >1.10 positive | ||||

| Anti‐HAV IgG | Positive | |||||

| Anti‐HAV IgM | Negative | |||||

| HBSAg | Negative | |||||

| Anti‐HBV surface | Negative | |||||

| Anti‐HBV core | Negative | |||||

| Anti‐HCV | Negative | |||||

| HSVI Ab | >5.00 | 0.00–0.89 | ||||

| HSV II Ab | 4.35 | 0.00–0.89 | ||||

| Lyme Ab | 0.64 | <1.00 | ||||

| Cerebrospinal fluid | ||||||

| WBC | 2 | 4 | per mm3 | |||

| Lymphocytes | 92 | % | ||||

| Neutrophils | 8 | % | ||||

| Monocytes | 0 | % | ||||

| Eosinophils | 0 | % | ||||

| Basophils | 0 | % | ||||

| Cytology | No malignant cells | No malignant cells | ||||

| Macrophages | 4 | Per 100 WBC | ||||

| RBC | 58 | 350 | Per mm3 | |||

| Glucose | 64 | 51 | 40–70 mg/dl | |||

| Protein | 124 | 119 | 15–45 mg/dl | |||

| Lactate | 2.0 | 0.6–2.20 mM/l | ||||

| Pyruvate | 0.10 | 0.04–0.13 mM/l | ||||

| HSV 1 and 2 PCR | Negative | Negative | ||||

| VZV PCR | Negative | |||||

| West Nile virus PCR | Negative | |||||

| St Louis encephalitis PCR | Negative | |||||

| Eastern equine encephalitis PCR | Negative | |||||

| Cache Valley and California serogroup viruses PCR | Negative | |||||

| Enterovirus PCR | Negative | |||||

| EBV PCR | Negative | |||||

| CMV PCR | Negative | |||||

| IgG | 16.4 | 0.5–6.0 mg/dl | ||||

| IgG/total protein | 13.8 | 6.0–13.0% | ||||

Ab, antibody; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspertate aminotransferase; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CMV, cytomegalo virus; CRP, C reactive protein; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; ENA, extractable nuclear antigens; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAV, hepatitis A virus; Hgb, haemoglobin; HSV, herpes simplex virus; Ig, immunoglobulin; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; NR, not reported; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; Plt, platelet count (×1000); RF, rheumatoid factor; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; TSH, thyroid‐stimulating hormone; VZV, varicella zoster virus; WBC, white blood cell count.

Brain biopsy showed transmural, predominantly eosinophilic, inflammatory infiltrates of medium‐sized leptomeningeal arteries (fig1C, D, black arrows). Small cortical vessels showed focal fibrinoid necrosis and swollen endothelial cells, without granulomas. Immunoperoxidase staining for amyloid‐β peptide in cortical and subpial vessels showed no evidence of amyloid angiopathy. Gram stain, bacterial culture, staining for acid‐fast bacilli and mycobacterial culture of the brain biopsy were all negative. No viral inclusions were identified, and immunohistochemical stains for HSV‐1, HSV‐2 and varicella were negative.

Figure 1 (A) Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) post‐gadolinium T1 sequence shows right occipital, anterior frontal, and bilateral parietal cortical lesions with leptomeningeal enhancement on the T1‐weighted images (black arrowheads). (B) FLAIR image shows high signal of the cortical mantle as well as the subarachnoid space in the adjacent gyri (white arrowheads). The bifrontal lesions observed on MRI during the patient's previous hospitalisation show evolution (white arrow). (C, D) Histological examination shows transmural, predominantly eosinophilic, inflammatory infiltrates of medium‐sized leptomeningeal arteries (black arrows). Small cortical vessels showed focal fibrinoid necrosis and swollen endothelial cells, without granulomas.

The patient received high‐dose intravenous dexamethasone with rapid improvement in symptoms. She had normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein levels within 2 weeks of steroid therapy, and was discharged on a prednisone taper followed by a low maintenance dose. One year later she has mild residual left‐sided sensory loss without recurrence of symptoms; MRI showed gyral volume loss and encephalomalacia.

Discussion

Eosinophilic vasculitis is a feature of certain rheumatological conditions, but is rare in an isolated CNS distribution.3 Stroke caused by vasculitis is well described in the Churg–Strauss syndrome, which is characterised by multisystem granulomatous eosinophilic vasculitis accompanied by peripheral eosinophilia and a history of asthma.4 Granulomatous eosinophilic vasculitis accompanied by mild peripheral eosinophilia has been observed in parenchymal and leptomeningeal vessels affected by cerebral amyloid angiopathy.5 Eosinophilic temporal arteritis and claudicating systemic arteritis, associated with a 24% peripheral eosinophil count, was reported with vasculitic vertebrobasilar stroke, although no aetiology was identified.6 Here we describe a non‐granulomatous eosinophilic vasculitis of the CNS with no accompanying eosinophilia of the peripheral blood or CSF, and no involvement of other organ systems. Given their similarities, her two isolated episodes may probably be due to the same disorder. Lack of peripheral eosinophilia argues against systemic infection or drug reaction. The absence of granulomas further distinguishes this case histopathologically from nearly all other reported cases of isolated CNS vasculitis. Although her MRI findings could indicate focal lobar oedema with haemosiderin deposition, the condition argues against cerebral amyloid angiopathy or amyloid‐β‐related angiitis, which has been recently described as a reversible cerebral amyloid angiopathy leucoencephalopathy syndrome with associated angiitis.7,8 No aetiology for this patient's primary CNS eosinophilic vasculitis has yet been identified. Spontaneous resolution and recurrence of her syndrome is an unusual feature of the typical CNS vasculitis and may suggest an environmental epitope with immune reaction as the cause.

Acknowledgements

We have no financial or other disclosures to report, but are grateful to Timothy S Lo, MD, of the Neurological Institute, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, for his assistance with this report.

Abbreviations

CSF - cerebrospinal fluid

CNS - central nervous system

HSV - herpes simplex virus

MRI - magnetic resonance imaging

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Guillevin L, Cohen P, Gayraud M.et al Churg‐Strauss syndrome: clinical study and long term followup of 96 patients. Medicine January19997826–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sehgal M, Swanson J W, DeRemee R A.et al Neurologic manifestations of Churg‐Strauss syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc 199570337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidley J W.Central nervous system angiitis. Boston: Butterworth‐Heineman, 2000102–103.

- 4.Dinc A, Soy M, Pay S.et al A case of Churg‐Strauss syndrome presenting with cortical blindness. Clin Rheumatol 200019318–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fountain N, Eberhard D A. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy: report of two cases and a review of the literature. Neurology 199646190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grishman E, Wolfe D, Spiera H. Eosinophilic temporal and systemic vasculitis. Hum Pathol 199525241–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scolding N J, Joseph F, Kirby P A.et al A beta‐related angiitis: primary angiitis of the central nervous system associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain 2005128(Pt 3)500–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oide T, Tokuda T, Takei Y.et al Serial CT and MRI findings in a patient with isolated angiitis of the central nervous system associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Amyloid 20029256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]