Abstract

Background

Conventional MRI can provide critical information for care of patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI), but MRI abnormalities rarely correlate to clinical severity and outcome. Previous magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies have reported clinically relevant brain metabolic changes in patients with TBI. However, these changes were often assessed a few to several days after the trauma, with a consequent variation of the metabolic pattern due to temporal changes.

Methods

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (1H‐MRSI) examinations were performed in 10 patients with TBI 48–72 h after the trauma, to obtain early measurements of central brain levels of N‐acetylaspartate (NAA), choline (Cho), creatine (Cr) and lactate (La). Metabolite values were expressed as ratios to (1) a metabolic pattern, given by the sum of the resonance intensities of all metabolites detected in the same voxel and (2) intravoxel Cr.

Results

NAA ratios were found to be significantly lower in patients with TBI than in normal controls. In contrast, Cho ratios were significantly higher in patients with TBI than in normal controls. Increased La levels were found in 5 of 10 patients with TBI. Both NAA and La values correlated closely with those of the Glasgow Coma Scale at presentation (r = 0.73 and −0.62, respectively; p<0.01 for both) and the Glasgow Outcome Scale at 3 months (r = −0.79 and 0.79, respectively; p<0.01 for both).

Conclusion

Spectroscopic measures of neuro‐axonal damage occurring soon after a brain trauma are clinically relevant. Significant increases in cerebral La level also may be detected when 1H‐MRSI is performed early after the trauma and, at this stage, can represent a reliable index of injury severity and disease outcome in patients with TBI.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a common cause of neurological damage and disability. Conventional imaging (CT scan or MRI) is highly sensitive in detecting lesions and provides critical information for guiding the care of patients with TBI, especially in the acute stage of the injury.1 However, abnormalities detected by CT scan or conventional MRI have limited importance in the classification of the degree of clinical severity and in predicting patients' outcome.2 This can be explained by the widespread microscopic tissue damage occurring after trauma, which is not observable with the conventional structural imaging methods.3,4

Using the same equipment used for conventional MRI, single‐voxel proton magnetic resonance (MR) spectroscopy (1H‐MRS) and multi‐voxel proton MR spectroscopic imaging (1H‐MRSI) can explore in vivo the intracellular metabolic status, and can give direct evidence of microscopic injury.5 The metabolites detected by 1H‐MRS and 1H‐MRSI are sensitive to hypoxia, energy dysfunction, neuronal injury, membrane turnover and inflammation—all conditions potentially implicated in TBI. Thus, in recent years, both 1H‐MRS and 1H‐MRSI have been used to non‐invasively evaluate cellular injury in patients with TBI, showing, in some occasions, their potential to assess clinical severity and to predict disease outcome.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16

In most of the spectroscopic studies reported so far, however, subjects have been studied only when medical conditions were stabilised and, with some exceptions,8,13,16 the time of the spectroscopic examination varied greatly (from a few days to several months) even in the same study.17 This has important implications for the interpretation of the results, as the metabolic pattern may change greatly with time. Thus, for example, the decrease in N‐acetylaspartate (NAA) level seems to start from a few minutes after the trauma, reaching its maximum in 48 h and recovering thereafter if the brain injury was mild or moderate.18 Similarly, increases in parenchymal lactate (La) can be seen exclusively in the earliest stage of post‐trauma.17

In an attempt to detect acute metabolic changes while minimising variations of the metabolic pattern due to temporal evolution, we performed multi‐voxel brain 1H‐MRSI examinations in patients with several degrees of TBI 48–72 h after the trauma. In these acute conditions, we also assessed the relevance of the metabolic indices provided by 1H‐MRSI to injury severity at presentation and short‐term disease outcome.

Material and methods

Study population

We studied 10 patients admitted to the Siena University Hospital, Siena, Italy, because of moderate to severe TBI (3 women and 7 men, mean (range) age 44.6 (21–77) years). Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical data of the patients with TBI. All patients underwent combined conventional MRI and 1H‐MRSI examination 48–72 h after the brain trauma. During the MR examination, intensive monitoring of blood pressure, pulse oximetry and blood gases was done according to current guideline recommendations.19 Sedation was maintained with a continuous intravenous infusion of fentanil, propofol and midazolam. On each occasion, a neuro‐anaesthetist (EZ) was present in the magnet room throughout the MR examination. In each patient, the severity of the head injury was assessed at presentation using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS).20 The outcome at 3 months was assessed by the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS),21 the modified reversed version (death = 5; persistent vegetative state = 4; severe disability = 3; moderate disability = 2; good recovery = 1) that has become a common practice in clinical trial administration.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical data of patients with traumatic brain injury.

| Patients with TBI | Age (years) | Sex | GCS | GOS | Cause of TBI | MRI findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 69 | M | 4 | 5 | Fall | Left frontoparietal focal abnormality |

| 2 | 21 | M | 6 | 4 | MVA | Diffuse abnormalities |

| 3 | 51 | F | 6 | 3 | MVA | Interhemispheric focal abnormality |

| 4 | 31 | F | 5 | 3 | MVA | Diffuse abnormalities |

| 5 | 31 | F | 8 | 1 | MVA | Unremarkable |

| 6 | 61 | M | 7 | 2 | Fall | Right frontal focal abnormality |

| 7 | 34 | M | 5 | 1 | MVA | Unremarkable |

| 8 | 77 | M | 4 | 4 | Fall | Diffuse abnormalities |

| 9 | 28 | M | 12 | 1 | MVA | Right frontal focal abnormality |

| 10 | 43 | M | 13 | 1 | MVA | Right frontal focal abnormality |

F, female; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; GOS, Glasgow Outcome Scale; M, male; MVA, motor vehicle accident; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

1H‐MRSI values of subjects with TBI were compared with those of a group of 10 age‐ and sex‐matched normal controls (NC, 3 women and 7 men, mean (range) age 41.4 (22–60) years).

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Siena, and informed consent was obtained from the patients' closest relative.

MR examination

All subjects were examined using an identical MR protocol, which included combined conventional MRI and 1H‐MRSI examinations of the brain. Acquisitions of brain were obtained in a single session of 50 min for each examination using a Philips Gyroscan operating at 1.5 T (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands). A sagittal survey image was used to identify the anterior commissure and posterior commissure. A dual‐echo, turbo spin‐echo sequence (repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE)1/TE2 = 2075/30/90 ms, 256×256 matrix, 1 signal average, 250 mm field of view, 50 contiguous 3 mm slices) yielding proton density‐weighted and T2‐weighted (T2W) images was acquired in the transverse plane, parallel to the line connecting the anterior commissure and posterior commissure. Fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery images (TR = 9000 ms; TE = 150 ms; 50 contiguous 3 mm slices) were acquired in the same direction.

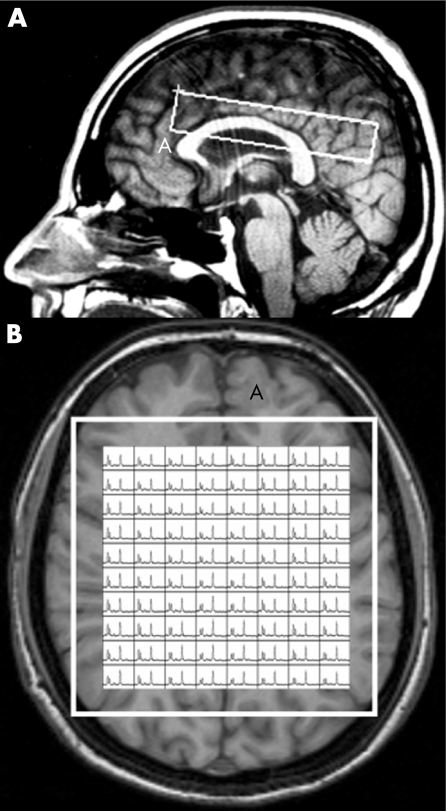

The MR images were used to select an intracranial volume of interest (VOI) for spectroscopy, measuring approximately 100 mm antero‐posterior × 20 mm cranio‐caudal × 90 mm left–right. This was centred on the corpus callosum to include mostly white matter and some mesial cortex of both hemispheres (fig 1). Two‐dimensional spectroscopic images were obtained using a 90°–180°–180° pulse sequence (TR = 2000 ms, TE = 272 ms, 250 mm field of view, 32×32 phase‐encoding steps, 1 signal average per step) as described previously.22 Magnetic field homogeneity was optimised to a line width of about 5 Hz over the VOI, using the proton signal from water. Water suppression was achieved by placing frequency‐selective excitation pulses at the beginning of the MRSI sequence. Before the water‐suppressed acquisition, another MRSI was acquired without water suppression (TR = 850 ms, TE = 272 ms, 250 mm field of view and 16×16 phase‐encoding steps) to allow for B0 homogeneity correction.

Figure 1 MRI images in sagittal (A) and transversal (B) orientations of a normal control, illustrating the volume of interest (VOI) used for spectroscopic imaging. In (B), an example is shown of the resulting spectra in the entire VOI. Voxels at the edges of the VOI were not used as they can show artifactual relative amplitudes (see Materials and methods).

1H‐MRSI data analysis

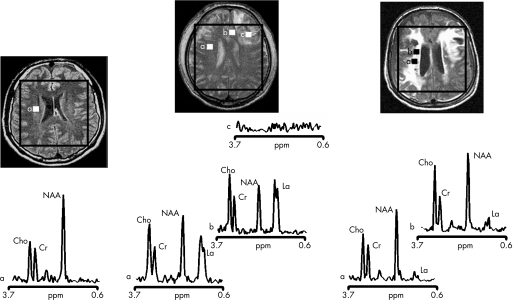

In all subjects, post‐processing of the raw 1H‐MRSI data was performed as described previously.22 The nominal voxel size of raw 1H‐MRSI data was 8×8×20 mm, giving a resolution of about 12×12×20 mm after k‐space filtering. In these cerebral volumes, resonance intensity values of N‐acetyl groups (mainly NAA), choline (Cho, choline‐containing compounds arising mainly from tetramethylamines), creatine (Cr), and phosphocreatine and La were determined. Using this method, La resonance intensities can be detected only under pathological conditions, as it is below detection limits in the normal brain.5,23,24 Resonance intensity values of metabolite were assessed using a combination of Xunspec1 software (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, Massachusetts, USA) and a free software developed at the Montreal Neurological Institute (AVIS; Samson Antel PhD, Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Unit, MNI, Montreal, Canada). Using this software, gaussian‐fitted peak areas were determined relative to a baseline computed from a moving average of the noise regions of each spectrum. No attempt was made to provide an absolute quantitation of our 1H‐MRSI data for the known complexity and inaccuracies of deriving absolute mmol/l concentrations from in vivo 1H‐MRSI data,25,26 which would require knowledge about individual relaxation parameters and correction for spatial variations of the excitation pulse and Bo inhomogeneities. However, as the Cr resonance intensity, which has been widely used as an internal standard in MRS studies in vivo, may easily change in acute conditions,23 here we preferred to normalise the resonance intensities of each metabolite for the sum of the resonance intensities of all metabolites detected in the same voxel (Mettot; ie, the sum of NAA, Cho, and Cr in 1H‐MRSI). Mean values of NAA/Mettot, Cho/Mettot and Cr/Mettot of the whole brain region were then obtained by averaging each value for all the voxels in the spectroscopic VOI for each subject. Values of La/Mettot were calculated by averaging only voxels with detectable La resonance intensities (table 2). In 2 patients (patients 1 and 3 in table 1) with focal haematoma, voxels inside the focal lesion were excluded (1.5% and 13% of the voxels in the VOI, respectively) to avoid the artefacts derived by the cerebral haemorrhagic contusion (fig 2). As chemical shift artefacts associated with selective excitation might affect spectra at the edges of the VOI, they were deleted before averaging (fig 1).

Table 2 Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging data (metabolite ratios) of patients with traumatic brain injury (see Materials and methods for details).

| Patients with TBI | NAA/Mettot | NAA/Cr | Cho/Mettot | Cho/Cr | Cr/Mettot | La/Mettot | La/Cr | % La in VOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.42 | 2.82 | 0.24 | 1.59 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 1.06 | 77 |

| 2 | 0.05 | 0.63 | 0.60 | 5.18 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 1.02 | 89 |

| 3 | 0.49 | 2.85 | 0.30 | 1.63 | 0.19 | ND | ND | — |

| 4 | 0.08 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 2.74 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 1.35 | 98 |

| 5 | 0.51 | 2.84 | 0.29 | 1.58 | 0.19 | ND | ND | — |

| 6 | 0.46 | 2.57 | 0.30 | 1.70 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 53 |

| 7 | 0.48 | 2.66 | 0.32 | 1.78 | 0.18 | ND | ND | — |

| 8 | 0.40 | 2.34 | 0.32 | 1.80 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 59 |

| 9 | 0.53 | 2.92 | 0.28 | 1.55 | 0.18 | ND | ND | — |

| 10 | 0.53 | 3.02 | 0.28 | 1.63 | 0.18 | ND | ND | — |

| NC (mean (SD)) | 0.55 (0.03) | 3.03 (0.29) | 0.25 (0.02) | 1.41 (0.18) | 0.19 (0.01) | ND | ND | — |

Cho, choline; Cr, creatine; La, lactate; Mettot, sum of the resonance intensities of all metabolites detected in a given voxel; NAA, N‐acetylaspartate; ND, not detected; VOI, volume of interest.

%La in VOI, percentage of voxels containing lactate in the cerebral volume of interest for spectroscopy.

Values that are 2 SDs lower or higher than the means of normal controls are in bold.

Figure 2 Proton magnetic resonance spectra and conventional magnetic resonance images showing the volume of interest for spectroscopic imaging of a normal control (left panel), patient 1 (central panel) and patient 8 (right panel) with traumatic brain injury (TBI). On conventional MRI, patient 1 shows a focal haematoma in the frontal left hemisphere and patient 8 shows diffuse MRI abnormalities. Spectra show decreases of N‐acetylaspartate (NAA) and increases of choline (Cho) and lactate (La) in patients with TBI (a and b in central and right panels) with respect to the normal control (a in left panel). The spectra of patient 1 (central panel) show more pronounced metabolic abnormalities than those of patient 8 (right panel), despite the fact that patient 8 showed markedly more abnormalities on conventional MRI. In the spectra of patient 1 (central panel), metabolic abnormalities are clearly evident in the normal appearing brain. Finally, in patient 1, voxels inside the focal haematoma (c in central panel) were excluded to avoid the artefacts that could be derived by the cerebral haemorrhagic contusion. Cr, creatine.

Statistical analysis

Owing to the small sample size of this study, which might probably have a non‐gaussian distribution, non‐parametric statistical tests were used. Central brain 1H‐MRSI values of subjects with TBI were compared with those of the NC group using the non‐parametric Mann–Whitney U test. Values of 1H‐MRSI indices of the subjects with TBI were correlated with their corresponding GCS and GOS scores using the non‐parametric Spearman rank order correlation. Values were considered significant at the 0.05 level. The SYSTAT software V.9 running on Windows was used to perform statistical calculations.

Results

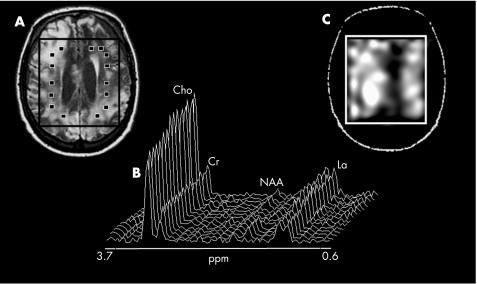

Table 2 summarises values relative to the metabolite ratios of patients with TBI and NC. Central brain values of NAA/Mettot were lower in patients with TBI than in NC (mean (SD) NAA/Mettot in patients with TBI = 0.39 (0.18); mean (SD) NAA/Mettot in NC = 0.55 (0.03); p<0.001). In contrast, Cho/Mettot values were higher in patients with TBI than in NC (Cho/Mettot in patients with TBI = 0.34 (0.11); Cho/Mettot in NC = 0.25 (0.02); p<0.005). Increased levels of parenchymal La/Mettot were found in 5 of 10 patients with TBI (figs 2 and 3). In these patients, the increase in La level was diffuse in the VOI (fig 3), with the percentage of voxels with detectable La ranging from 53% to 98% (table 2). No significant changes in Cr/Mettot levels were found between patients with TBI and NC. As a corollary, values of NAA, Cho and La expressed as ratios to Cr value were similar to those reported as ratios to the sum of MRS metabolites: NAA/Cr in patients with TBI versus NC: p<0.02; Cho/Cr in patients with TBI versus NC: p<0.005; La/Cr was detected in 5 of 10 patients with TBI (table 2).

Figure 3 Conventional MRI transversal orientation of patient 4 showing diffuse abnormalities (A); proton magnetic resonance spectra (B) from several voxels of the volume of interest (VOI; ▪) showing the very large and diffuse decrease in the N‐acetylaspartate (NAA) resonance intensity and the widespread increases in the choline (Cho) and lactate (La) resonance intensities, and the crude spectroscopic image of La (C) showing that La was largely increased in the entire VOI in this patient with traumatic brain injury. Cr, creatine.

The metabolic abnormalities detected through the 1H‐MRSI VOI appeared to be unrelated to the abnormalities detected on conventional MRI (fig 2).

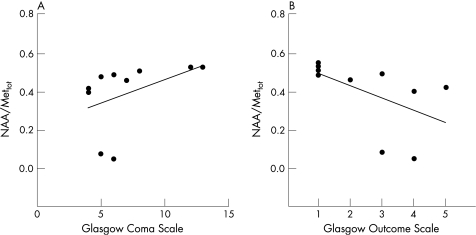

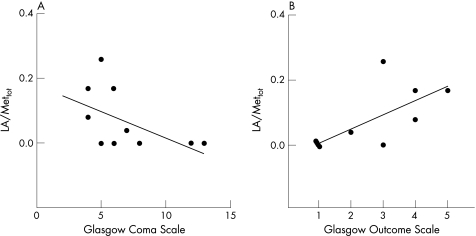

Values of the metabolite ratios of patients with TBI were then correlated to GCS at presentation and GOS at 3 months for each patient with TBI (table 3). In this patient group, NAA/Mettot values showed a very close positive correlation with GCS (r = 0.73; p = 0.008) and a negative correlation with GOS (r = −0.79; p = 0.009; fig 4A and B). In addition, La/Mettot values showed very close correlations with both GCS (r = −0.62; p = 0.05) and GOS (r = 0.79; p = 0.005; fig 5A and B). Similar results were obtained when the percentage of voxels with detectable La in the brain VOI was correlated with values of GCS and GOS. In contrast, no significant correlations with GCS and GOS were found for both choline/Mettot and creatine/Mettot (table 3).

Table 3 Correlations between proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging data (metabolite ratios) and Glasgow Coma Scale and Glasgow Outcome Scale.

| TBI | r | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| NAA/Mettot vs GCS | 0.73 | 0.008 |

| Cho/Mettot vs GCS | −0.35 | 0.7 |

| Cr/Mettot vs GCS | −0.014 | 0.9 |

| La/Mettot vs GCS | −0.62 | 0.05 |

| NAA/Mettot vs GOS | −0.79 | 0.009 |

| Cho/Mettot vs GOS | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Cr/Mettot vs GOS | 0.16 | 0.7 |

| La/Mettot vs GOS | 0.79 | 0.005 |

Cho, choline; Cr, creatine; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; GOS, Glasgow Outcome Scale; La, lactate; NAA, N‐acetylaspartate; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Figure 4 Scatter plots illustrating the close relationship of central brain N‐acetylaspartate (NAA)/Mettot measurements and both Glasgow Coma Scale (A, Spearman's rank correlation = 0.73; p = 0.008) and Glasgow Outcome Scale (B, Spearman's rank correlation = −0.79; p = 0.009).

Figure 5 Scatter plots illustrating the close relationship of central brain lactate (La)/Mettot measurements and both Glasgow Coma Scale (A, Spearman's rank correlation = −0.62; p = 0.05) and Glasgow Outcome Scale (B, Spearman's rank correlation = 0.79; p = 0.005).

Discussion

The neuropathology of TBI is complex. Together with a primary injury due to the mechanical disruption occurring at the time of the trauma, a secondary injury mechanism, initiated by the primary traumatic event, manifests quite soon.27 This is mostly interpreted as diffuse axonal damage, but may include, more generally, cell necrosis and apoptosis, increased cell membrane turnover, glial proliferation, inflammation and energy dysfunction.3,4,28,29 All these complex biochemical and pathophysiological processes are difficult to visualise with the conventional structural imaging methods, and, although CT and MRI are shown to be very sensitive in detecting macroscopic pathology occurring after a trauma, overall, the presence of diffuse, microscopic injury remains mostly undetectable with conventional neuroimaging techniques.1

Some of the limitations of conventional neuroimaging have been overcome by using 1H‐MRS, which allows exploration in vivo of the intracellular metabolic status of the brains in patients with TBI.17 Thus, in previous studies, single‐voxel 1H‐MRS and multi‐voxel 1H‐MRSI have consistently found large increases in choline and diffuse decreases in NAA in the brains of patients with TBI.6

In this study, by performing multi‐voxel 1H‐MRSI of the brain, shortly after the trauma, we were able to confirm both widespread NAA decreases and choline increases in a small population of patients with different degrees of TBI. As choline peak detected by in vivo spectroscopy represents a combination of different choline‐containing compounds, all associated with membrane phospholipids,30 the diffuse elevation of choline after TBI may reflect membrane disruption and/or increased cell membrane turnover.6,17 In contrast, as NAA is localised almost exclusively to neurons and axons in the adult human brain,31,32 the finding of widespread low levels of NAA in TBI should be interpreted as due to permanent neuro‐axonal damage and/or loss5,17 or, in acute conditions such as those reported here, might also depend on potentially reversible axonal dysfunction due to post‐injury mitochondrial impairment.18,33 It must be emphasised, however, that recent studies have not found early changes in cerebral NAA in patients with moderate to severe TBI who underwent 1H‐MRSI within a few days after the trauma.13,16 Differences in the characteristics of the patient populations as well as small differences in 1H‐MRSI procedures (ie, acquisition and quantitation) and in the time frame between 1H‐MRSI acquisition and brain injury could be the reasons for the discrepancy between our study and those mentioned above. However, in vitro data showing that NAA decreases a few minutes after the trauma and reaches its maximum in 48 h18 seem to give support to our finding.

In addition to evidence of decreased NAA and increased choline, we found a diffusely high signal of La resonance intensity in the brains of 5 of 10 patients with acute TBI. The detection of the methyl doublet from La ranged from 53% to 98% of the voxels in the spectroscopic VOI, and largely included voxels with normal‐appearing brain on conventional MRI (fig 2). As the intracerebral La concentration is below the detection limit for the 1H‐MRSI method used in this study,5,24 the presence of the trace of La in brains must be an expression of pathological conditions occurring in the brain parenchyma34 and cerebrospinal fluid.35 These include impairment of the oxidative metabolism or infiltration of macrophages and inflammatory cells, all conditions that occur after a TBI.17

Although increases in brain parenchymal La level are often found in children,10,36 most of the spectroscopic studies on adults with injured brains either do not mention it or report focal La increases when the mechanism of injury is clearly ischaemic.14,17,37 The scarce evidence for increases in brain La level in previous spectroscopic studies of adult TBI may be a function of the time span between the initial insult and the imaging examination. In previous studies, the imaging examination was usually performed several days or even months after the trauma, when La increases might have disappeared. In agreement with this, experimental work has shown that cerebral La increases progressively soon after the brain injury and decreases after 1 week.38 It should be mentioned, however, that in the few reported cases with 1H‐MRS8 or 1H‐MRSI13,16 performed early after the trauma, increases in brain La were found in only two patients,8 and that this was found only in 50% of our patient population. Despite these limitations, the results of this study suggest that 1H‐MRSI can provide, in some circumstances, an accurate estimation of the impairment of the energy metabolism occurring in the brains of patients with TBI, and give support to the importance of controlling and possibly reducing the time between the injury and the spectroscopic examination.

Previous spectroscopic studies and experimental work that examined the correlations between altered brain metabolite levels and injury severity or clinical outcome have reached the common conclusion that brain levels of NAA measured within several days or weeks from injury can provide a good index of disease severity and outcome.6,7,9,11,12,15,18,39 Data reported here confirmed this notion by showing a very close correlation between NAA/Mettot and measures of initial disease severity and short‐term clinical outcome. In this study, however, we also found a very close correlation between the scores of clinical severity and outcome and the levels of central brain La. This close relationship between clinical scores and brain parenchymal levels of La was never reported in previous spectroscopic studies, probably due to the already mentioned tendency to perform the spectroscopic examination in the subacute or even chronic state, when medical conditions might have stabilised. In contrast, by performing the 1H‐MRSI examination on each patient with TBI 48–72 h after the trauma, we detected La resonance intensities in a measure that was proportional to initial clinical severity and short‐term disease outcome. This suggests that pathological processes (ie, mitochondrial alterations, inflammation, etc) leading to acute impairment of oxidative metabolism are clinically relevant in TBI. The recent microdialysis data showing that, up to 2 days after injury, La at levels detectable by in vivo spectroscopy is associated with poor clinical outcome40 lend further support to this hypothesis.

The close relationships of both NAA and La metabolite intensities with clinical severity and outcome are potentially very interesting on clinical grounds. However, we emphasise here the good predictions of clinical outcome for NAA and La resonance intensities in a very short‐term period (3 months). Clinically, it would be much more interesting to know whether the brain levels of these compounds can predict long‐term outcome (ie, over 12 months). Unfortunately, this could not be done in the present patient population.

The current setting for spectroscopic studies on clinical MR scans implies the localisation of a brain volume from which the metabolic information can be collected. However, given the widespread nature of TBI, it is important that the spectroscopic measurement covers a large brain region. This aim can be reasonably achieved by using multi‐voxel 1H‐MRSI, which has the ability to provide biochemical information from voxels of about 1 cm3 in quite a large portion of brain tissue (fig 1). In addition, in this study, 1H‐MRSI data were collected from a brain VOI that was centred on the corpus callosum and included a large portion of the white matter as well as some mesial cortex of both hemispheres. All these regions, although comprehensive of only a limited portion of the whole brain, include brain areas that are well known to be involved in brain trauma7,14 and where axonal projections converge after traversing large brain volumes. Thus, as suggested by a recent 1H‐MRSI study,41 measures from this deep, central brain region should reflect the metabolic status of axons and other brain tissue cells in a fairly large volume of brain beyond that contained within the spectroscopic VOI.

Owing to the well‐known difficulties in deriving absolute concentrations from spectroscopic data,25 results of most of the previous studies have been normalised for the resonance intensity of Cr (expression of Cr and phosphocreatine), as this is relatively equally present in all brain cells and tends to be stable.5 Several studies, however, have shown that Cr resonance intensity may change, especially in acute conditions.23 Thus, we expressed our 1H‐MRSI data of each metabolite also as ratios to the sum of the resonance intensities of all metabolites detected in the same voxel. This implies that each measure is not relative to a single metabolite, but is rather an expression of a pattern in which each metabolite is in turn differently weighted. Interestingly, whereas group measurements of NAA/Mettot, Cho/Mettot and La/Mettot differed for patients with TBI and NC, values of Cr/Mettot did not change. This might suggest that, even in acute TBI, Cr resonance intensity tends to be more stable than the other metabolites detected by in vivo 1H‐MRSI.

In conclusion, by performing multi‐voxel 1H‐MRSI examination in a central brain region early (48–72 h) after the trauma, we found that, with neuro‐axonal damage and increased membrane turnover, a significant impairment of the oxidative metabolism also occurs (and can be detected) soon after a brain trauma. By keeping the time of 1H‐MRSI examinations homogeneous, we minimised brain metabolic fluctuation occurring after the trauma and were able to demonstrate that measures of early axonal damage/dysfunction such as NAA and also brain changes in La can be clinically relevant in these conditions. Thus, spectroscopic measures of acute impairment of oxidative metabolism can be used to estimate clinical severity at presentation and short‐term disease outcome in patients with TBI.

Acknowledgements

AF was supported in part by a grant from Regione Toscana. We thank Arlene Cohen for revising the manuscript language and Susanna Brogi for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

Cho - choline

Cr - creatine

GCS - Glasgow Coma Scale

GOS - Glasgow Outcome Scale

1H‐MRS - voxel proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy

1H‐MRSI - proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging

La - lactate

MR - magnetic resonance

NAA - N‐acetylaspartate

NC - normal control

TBI - traumatic brain injury

TE - echo time

TR - repetition time

VOI - volume of interest

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Gentry L R. Imaging of closed head injury. Radiology 19941911–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson J T, Wiedmann K D, Hadley D M.et al Early and late magnetic resonance imaging and neuropsychological outcome after head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 198851391–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams J H, Doyle D, Ford I.et al Diffuse axonal injury in head injury: definition, diagnosis and grading. Histopathology 19891549–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Povlishock J T, Katz D I. Update of neuropathology and neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 20052076–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold D L, Matthews P M. Practical aspects of clinical applications of MRS in the brain. In: Young IR, et al eds. MR spectroscopy: clinical applications and techniques London: Martin Dunitz, 1996139–159.

- 6.Ross B D, Ernst T, Kreis R.et al 1H MRS in acute traumatic brain injury. J Magn Reson Imaging 19988829–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cecil K M, Hills E C, Sandel M E.et al Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy for detection of axonal injury in the splenium of the corpus callosum of brain‐injured patients. J Neurosurg 199888795–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Condon B, Oluoch‐Olunya D, Hadley D.et al Early 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy of acute head injury: four cases. J Neurotrauma 199815563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman S D, Brooks W M, Jung R E.et al Quantitative proton MRS predicts outcome after traumatic brain injury. Neurology 1999521384–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashwal S, Holshouser B A, Shu S K.et al Predictive value of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in pediatric closed head injury. Pediatr Neurol 200023114–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garnett M R, Blamire A M, Corkill R G.et al Early proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in normal‐appearing brain correlates with outcome in patients following traumatic brain injury. Brain 20001232046–2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garnett M R, Blamire A M, Rajagopalan B.et al Evidence for cellular damage in normal‐appearing white matter correlates with injury severity in patients following traumatic brain injury: a magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Brain 20001231403–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Signoretti S, Marmarou A, Fatouros P.et al Application of chemical shift imaging for measurement of NAA in head injured patients. Acta Neurochir Suppl 200281373–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Govindaraju V, Gauger G E, Manley G T.et al Volumetric proton spectroscopic imaging of mild traumatic brain injury. Am J Neuroradiol 200425730–737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpentier A, Galanaud D, Puybasset L.et al Early morphologic and spectroscopic magnetic resonance in severe traumatic brain injuries can detect “invisible brain stem damage” and predict “vegetative states”. J Neurotrauma 200623674–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holshouser B A, Tong K A, Ashwal S.et al Prospective longitudinal proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging in adult traumatic brain injury. J Magn Reson Imaging 20062433–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks W M, Friedman S D, Gasparovic C. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 200116149–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Signoretti S, Marmarou A, Tavazzi B.et al N‐acetylaspartate reduction as a measure of injury severity and mitochondrial dysfunction following diffuse traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 200118977–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maas A I, Dearden M, Teasdale G M.et al EBIC‐guidelines for management of severe head injury in adults. European Brain Injury Consortium. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1997139286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 1974281–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet 19751480–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Stefano N, Narayanan S, Francis G S.et al Evidence of axonal damage in the early stages of multiple sclerosis and its relevance to disability. Arch Neurol 20015865–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Stefano N, Matthews P M, Antel J P.et al Chemical pathology of acute demyelinating lesions and its correlation with disability. Ann Neurol 199538901–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dubeau F, De Stefano N, Zifkin B G.et al Oxidative phosphorylation defect in the brains of carriers of the tRNAleu(UUR) A3243G mutation in a MELAS pedigree. Ann Neurol 200047179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barantin L, Le P A, Akoka S. A new method for absolute quantitation of MRS metabolites. Magn Reson Med 199738179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLean M A, Woermann F G, Barker G J.et al Quantitative analysis of short echo time (1)H‐MRSI of cerebral gray and white matter. Magn Reson Med 200044401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faden A I. Neuroprotection and traumatic brain injury: theoretical option or realistic proposition. Curr Opin Neurol 200215707–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cecil K M, Lenkinski R E, Meaney D F.et al High‐field proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of a swine model for axonal injury. J Neurochem 1998702038–2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cernak I, Vink R, Zapple D N.et al The pathobiology of moderate diffuse traumatic brain injury as identified using a new experimental model of injury in rats. Neurobiol Dis 20041729–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller B L, Chang L, Booth R.et al In vivo 1H MRS choline: correlation with in vitro chemistry/histology. Life Sci 1996581929–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simmons M L, Frondoza C G, Coyle J T. Immunocytochemical localization of N‐acetyl‐aspartate with monoclonal antibodies. Neuroscience 19914537–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjartmar C, Battistuta J, Terada N.et al N‐acetylaspartate is an axon‐specific marker of mature white matter in vivo: a biochemical and immunohistochemical study on the rat optic nerve. Ann Neurol 20025151–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Stefano N, Matthews P M, Arnold D L. Reversible decreases in N‐acetylaspartate after acute brain injury. Magn Reson Med 199534721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prichard J W. What the clinician can learn from MRS lactate measurements. NMR Biomed 1991499–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeSalles A A, Kontos H A, Ward J D.et al Brain tissue pH in severely head‐injured patients: a report of three cases. Neurosurgery 198720297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holshouser B A, Ashwal S, Luh G Y.et al Proton MR spectroscopy after acute central nervous system injury: outcome prediction in neonates, infants, and children. Radiology 1997202487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macmillan C S, Wild J M, Wardlaw J M.et al Traumatic brain injury and subarachnoid hemorrhage: in vivo occult pathology demonstrated by magnetic resonance spectroscopy may not be “ischaemic”. A primary study and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002144853–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuhmann M U, Stiller D, Skardelly M.et al Metabolic changes in the vicinity of brain contusions: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and histology study. J Neurotrauma 200320725–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uzan M, Albayram S, Dashti S G.et al Thalamic proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in vegetative state induced by traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 20037433–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodman J C, Valadka A B, Gopinath S P.et al Extracellular lactate and glucose alterations in the brain after head injury measured by microdialysis. Crit Care Med 1999271965–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelletier D, Nelson S J, Grenier D.et al 3‐D echo planar (1) HMRS imaging in MS: metabolite comparison from supratentorial vs. central brain. Magn Reson Imaging 200220599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]