Abstract

Objective

The safety and tolerability of adjunctive tolcapone initiated simultaneously with levodopa was evaluated with a focus on increases in liver transaminase and hepatotoxicity.

Methods

677 levodopa‐naïve patients with early stage Parkinson's disease (PD) were randomised to receive placebo or tolcapone 100 mg three times daily, added to standard doses of levodopa plus carbidopa or benserazide.

Results

Increases in liver transaminase above the upper limit of normal (ULN) occurred in 69/342 (20.2%) and 92/335 (27.5%) patients in the placebo and tolcapone groups, respectively. Increases ⩾3 times the ULN occurred in 4/342 (1.2%) and 6/335 (1.8%) patients receiving placebo and tolcapone, respectively (p = 0.5). Liver transaminase values returned to normal in 65% of placebo and 80% of tolcapone treated patients. No instances of serious hepatotoxicity were seen. Diarrhoea was the most commonly reported AE—36/342 (11.0%) placebo v 98/335 (29.0%) tolcapone—and caused discontinuation in 9.9% of tolcapone treated patients. Overall, study discontinuation due to adverse effects was 2.9% in the placebo group and 17.3% in the tolcapone group.

Conclusions

Tolcapone seemed to be safe and was generally well tolerated as an adjunctive treatment in patients starting treatment with carbidopa/levodopa for symptomatic PD. Mild increases in transaminase levels—<3 times the ULN—occurred commonly in both placebo and tolcapone treated patients, whereas potentially serious increases of up to ⩾3 times the ULN were infrequent.

Keywords: tolcapone, levodopa, Parkinson's disease, liver transaminases, hepatoxicity, adverse events

Tolcapone, a potent inhibitor of catechol‐O‐methyltransferase (COMT), is an effective adjunct to levodopa/carbidopa treatment in patients with fluctuating and stable Parkinson's disease (PD).1,2,3,4,5,6,7 Despite a high level of clinical efficacy, its use has been limited by postmarketing concerns about its hepatic safety.8 A growing body of evidence now suggests that a wider margin of safety exists than previously reported. Concerns about liver toxicity have been modulated by a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms, comprehensive analysis of the three cases of fatal hepatic dysfunction that occurred in 1997 and 1998, and postmarketing evidence on a large number of patients, some of them prospectively analysed, documenting tolcapone's relative hepatic safety when appropriately administered and monitored.9,10 The reintroduction of tolcapone in Europe is further evidence of a new attitude toward the hepatic safety of the drug.

The primary objective of the study reported here was to evaluate whether treatment with levodopa plus adjunctive tolcapone, in patients with idiopathic PD previously naïve to levodopa treatment, would reduce the onset of clinically significant motor fluctuations over a period of up to 6 years, compared with levodopa monotherapy, and to determine the long term efficacy, tolerability, and safety of adjunctive tolcapone treatment in patients with idiopathic PD previously naïve to levodopa treatment. The study was prematurely discontinued when the drug was abruptly withdrawn from the European market by the European Medicine Evaluation Agency. The safety and tolerability data from the 677 patients who were treated for a mean duration of 216 days, none the less, provide valuable information. In particular, because the risk of serious hepatic injury has been reported only during the first 6 months of drug exposure, the length of this study was ideal for the purpose of assessing hepatotoxicity. We therefore conducted a comprehensive analysis of the safety and tolerability data from this study.

Materials and methods

Study design

This multicentre, randomised, placebo controlled, double blind, parallel group clinical trial of 677 patients was performed at 92 sites in Europe, the United States, and Canada. The study was designed to compare a fixed dose of tolcapone (100 mg three times daily) with placebo as an adjunct to levodopa/carbidopa treatment over a 6 year period in levodopa‐naïve patients with idiopathic PD. Started in July 1997, the study was terminated by the sponsor, Roche Pharmaceuticals, on 17 November 1998, because of concerns about the potential hepatotoxicity of tolcapone raised in the postmarketing period. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments or the laws and regulations of the country in which it was performed (whichever gave the patient greater protection). Institutional review board approval was obtained before the start of the study. All patients provided written informed consent for each study procedure.

Patients

Eligible patients were at least 30 years of age, had met the UK Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank Diagnostic Criteria (bradykinesia and at least one of the following: muscle rigidity; resting tremor; postural instability not caused by primary visual, vestibular, cerebellar, or proprioceptive dysfunction),11,12 and were clinically diagnosed as having idiopathic PD within 5 years before baseline assessment. Prior exposure to a centrally acting dopamine agonist or COMT inhibitor was not allowed. Previous treatment with up to 1 week of levodopa was allowed to determine response to treatment (that is, the test dose). Treatment with a β adrenergic receptor blocker for tremor was allowed if the drug regimen had been stable for at least 4 weeks preceding screening. Exclusion criteria included a history of psychological illness, depression, drug or alcohol abuse within 2 years of the study; aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels ⩾2 times the upper limit of normal (ULN); and vital signs, electrocardiogram (ECG), or a medical problem that would interfere with assessment of PD. Women were either postmenopausal or using a reliable, medically accepted method of contraception.

Treatment

Patients were randomly assigned using the method of minimisation13 to receive placebo or tolcapone (100 mg three times daily) on the morning after the baseline visit. The remaining two doses were taken at 6‐hour intervals thereafter. The first dose was given together with either standard‐release levodopa/benserazide or levodopa/carbidopa. The recommended starting dose of levodopa was 150 mg/day (50 mg three times daily). Sustained‐release formulations of levodopa and carbidopa were permitted only as an optional bedtime dose in patients with significant PD related night time symptoms.

After the first day of study treatment, the levodopa dosage could be adjusted as necessary according to the patient's response and the development of adverse events (AEs). Dose adjustments for levodopa were not allowed to exceed 50 mg at one time. Adjustments in the levodopa dosage were not permitted during the 2 weeks preceding any assessment visit except during the initial 3 month titration period. Assessment visits occurred monthly for 6 months, and every 3 months thereafter.

Study assessments

Screening and baseline assessments included a complete medical history and physical examination, clinical laboratory tests (complete blood cell count, blood chemistries, urine analysis), ECG, and vital signs (blood pressure, pulse, oral temperature). Investigators examined all patients at the time of day reportedly associated with optimal functioning, in the “on” state, and all subsequent examinations were carried out at approximately the same time of day.

Safety analysis

Clinical safety evaluations, including assessment of vital sign measurements and clinical laboratory tests, were performed at baseline, at the end of week 2, and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. Laboratory measurements of AST and ALT were performed at months 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 12, and every 6 months thereafter until termination of the study. AEs were evaluated by spontaneous reports and observation of patients at assessment visits. At every visit, the treating investigator inquired about AEs and evaluated them for their intensity (mild, moderate, or severe), seriousness, and relationship to the study drug. Levodopa‐induced dyskinesia was assessed using the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) subscale IVa (Complications of Therapy—Dyskinesias). When increased, transaminase values above the ULN were recorded categorically as ⩽3 times higher than the ULN, between 3 and 5 times the ULN, or >5 times the ULN. Patients who experienced diarrhoea during the study completed a 28 day daily diary of its occurrence that rated stool frequency and consistency, urgency, abdominal cramps, diarrhoea severity, and treatment.

Statistical analysis

The safety data, including data on all AEs, were tabulated and analysed using descriptive statistics. The incidence of an increase of liver transaminase values ⩾3 times the ULN was analysed using logistic regression. The increase of bilirubin to twice the ULN was also summarised. The incidence of diarrhoea and the onset and duration of the initial episode were recorded by treatment group, sex, and age, to determine if patients at this early stage of their disease had a similar profile for diarrhoea as patients with more advanced disease.

Based on a set of assumptions concerning the original intent and duration of the study, it was determined that 660 subjects (330 in each group) would be required to yield 80% power to detect a significant difference between groups using a log rank test of equality of survival curves. This recruiting objective was accomplished before termination of the study, but the study was stopped too early for the efficacy data to be analysed. No other tests of statistical significance were planned or performed.

Results

Demographics

A total of 679 patients were screened and 677 were randomised to treatment (335 to tolcapone and 342 to placebo). Table 1 shows the patient demographic characteristics and PD history. The treatment groups were similar with respect to age, sex, race, weight, and baseline disease characteristics. Most patients had mild disease (Hoehn and Yahr scale 1 to 2). A small percentage of patients in each treatment group had received limited prior treatment with levodopa—17/342 (5.0%) in the placebo group v 23/335 (6.9%) in the tolcapone group.

Table 1 Baseline demographics and Parkinson's disease characteristics.

| Characteristics | Placebo | Tolcapone |

|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 342 | 335 |

| Male (%) | 59 | 58 |

| Age (years), mean (range) | 64 (38–80) | 63 (36–78) |

| Weight (kg), mean (range) | 78 (38–191) | 76 (43–185) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 337 (98) | 324 (97) |

| Black | 0 | 3 (0.9) |

| Asian | 2 (0.6) | 3 (0.9) |

| Hispanic | 2 (0.6) | 4 (1.2) |

| Other | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Hoehn and Yahr stage, n (%)* | ||

| 1 or 1.5 | 137 (40.0) | 114 (34.2) |

| 2 or 2.5 | 180 (52.6) | 201 (60.2) |

| 3 | 23 (6.7) | 17 (5.1) |

| 4 or 5 | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) |

| Mean (SD) | 1.8 (0.62) | 1.9 (0.59) |

| Duration of PD (years), mean (range) | 2.0 (0–10) | 2.0 (0–8) |

| Duration of treatment (years), mean (range) | 0.4 (0–5) | 0.4 (0–5) |

| UPDRS score (I + II + III), mean (SD) | 31.9 (13.4) | 32.5 (13.9) |

| Levodopa dose (mg/day), mean (SD) | 305.8 (186) | 283.9 (181) |

*Hoehn and Yahr stage was not reported in one patient.

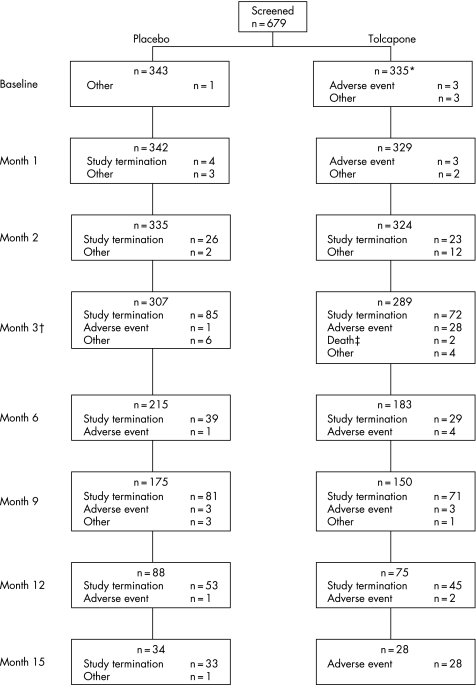

Levodopa dosage

The mean (SD) number of daily levodopa doses was 2.8 (0.8) at week 2, 2.9 (0.5) at month 15, and 2.8 (1.8) at the final visit in the tolcapone group; comparable values in the placebo group were 2.8 (0.8), 2.9 (1.0), and 2.8 (1.0). The mean (SD) total daily dose of levodopa increased from 156 (183) mg at week 2 to 358 (163) mg at month 15 in the placebo group and from 147 (68) mg at week 2 to 309 (166) mg at month 15 in the tolcapone group. Thus, the mean (SD) total daily dose of levodopa over the course of the entire study was higher in the placebo group than in the patients treated with tolcapone (306 (186) v 284 (181) mg). No difference was seen in the number of patients who received a bedtime dose of levodopa at least once during the study (3.3% placebo v 4.3% tolcapone). Treatment duration ranged from 1 week to 15 months (fig 1); the mean duration of treatment was slightly longer in the placebo group than in the tolcapone group (227 (121) v 206 (124) days).

Figure 1 Flow chart indicating patient disposition throughout study. *One patient was lost after screening, for unknown reasons. †Numbers shown for study withdrawal are cumulative to the next date shown, such that the number of patients shown as having withdrawn at month 3 is actually the number of patients who withdrew during months 3, 4 and 5. ‡Deaths were not attributable to the drug administered.

Safety and tolerability

Hepatic safety

A substantial percentage of patients had raised ALT or AST levels, or both, at screening: 19/342 (5.5%) in the placebo group and 23/335 (6.9%) patients in the tolcapone group (p = 0.5). During the study, 69/342 (20.2%) patients in the placebo group and 92/335 (27.5%) patients in the tolcapone group had at least one raised value above the ULN, including those with increased values at screening. Increases >3 times the ULN occurred in 6/335 (1.8%) tolcapone treated patients and 4/342 (1.2%) placebo treated patients (p = 0.5). Despite continuing treatment, transaminase levels returned to normal in six of these 10 patients; two patients were withdrawn, and the increase persisted in two patients at study end point. Only four patients altogether, three from the tolcapone group, were withdrawn because of raised AST/ALT levels, based on investigator and patient choice. In each of the three tolcapone treated patients, transaminase values returned to baseline levels when treatment was stopped. No patient in either group developed jaundice or hepatic insufficiency, and there were no admissions to hospital or deaths associated with liver disease. At the final visit, 24/342 (7.0%) placebo treated patients and 18/335 (5.4%) tolcapone treated patients had any increase in AST/ALT, with none having an increase ⩾3 times the ULN. Neither age nor sex were significantly associated by logistic regression with the occurrence of an increase in transaminase levels (p = 0.5 and p = 0.2, respectively).

In the tolcapone group, 75% of the increases were detected by 2 months, 90% by 3 months, and 97% by 6 months from baseline. The mean time to progression from the initial detection of a raised AST/ALT level to an increase ⩾3 times the ULN was comparable in both treatment groups (table 2).

Table 2 Progression of initial liver transaminase elevations to ⩾3 × ULN.

| Initially detected rise | Placebo (n = 342) | Tolcapone (n = 335) |

|---|---|---|

| ⩽2 × ULN, days (SD) | 38.5 (56.2) | 37.3 (21.5) |

| 2–3 × ULN, days (SD) | 8.8 (17.5) | 10.0 (15.6) |

Other adverse events

AEs were reported by 238 (70%) and 245 (73%) patients in the placebo and tolcapone groups, respectively. Most AEs were mild to moderate and consisted of diarrhoea, nausea, dizziness, headache, depression, upper respiratory tract infection, and fatigue (table 3). The most commonly reported AEs with an incidence of >2% were gastrointestinal system disorders (30% placebo v 48% tolcapone), followed by central and peripheral nervous system disorders (18% placebo v 19% tolcapone), psychiatric disorders (14% placebo v 11% tolcapone), and musculoskeletal system disorders (10% placebo v 9% tolcapone).

Table 3 Summary of adverse events with an incidence of ⩾2% in the safety population.

| Adverse event* | Placebo (n = 342) | Tolcapone (n = 335) |

|---|---|---|

| Diarrhoea | 36 (11) | 98 (29) |

| Nausea | 45 (13) | 67 (20) |

| Dizziness | 28 (8) | 34 (10) |

| Fatigue | 17 (5) | 13 (4) |

| Headache | 26 (8) | 23 (7) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 17 (5) | 16 (5) |

| Depression | 25 (7) | 16 (5) |

| Urine discolouration | 5 (2) | 10 (3) |

| Excessive dreaming | 15 (4) | 11 (3) |

| Dyskinesia | 3 (1) | 7 (2) |

*Results are shown as number (%).

Diarrhoea was the most commonly reported AE, affecting 36/342 (11%) and 98/335 (29%) patients in the placebo and tolcapone groups, respectively. The incidence was highest in patients aged 65–75, and similar for men and women. A higher incidence of moderate and severe diarrhoea, frequently accompanied by abdominal discomfort and cramping, occurred with tolcapone treatment than with placebo, whereas the number of cases of mild diarrhoea was similar in both treatment groups (6.7% in the placebo group and 7.7% in the tolcapone group; table 4). Most cases resolved or improved in both treatment groups.

Table 4 Intensity and outcome of first incidence of diarrhoea in the safety population.

| Maximum intensity | Placebo (n = 342) | Tolcapone (n = 335) |

|---|---|---|

| Mild, n (% of cases) | 23 (64) | 26 (27) |

| Moderate | 12 (33) | 47 (48) |

| Severe | 1 (3) | 25 (25) |

| Total, n (% of study group) | 36 (11.3) | 98 (30) |

| Outcome, n (% of cases) | ||

| Resolved/improved | 34 (94.4) | 92 (93.9) |

| Unchanged | 2 (5.6) | 6 (6.2) |

| Cited as a reason for discontinuing study | 2 (5.6) | 40 (40.8) |

The incidence of severe AEs was higher with tolcapone treatment than placebo: 59/335 (17.6%) tolcapone v 30/342 (8.8%) placebo. However, if diarrhoea was excluded, the incidence was similar, 30/335 (9.0%) tolcapone v 29/342 (8.5%) placebo. Severe treatment related AEs were experienced by 8/342 (2.3%) patients in the placebo group compared with 35/335 (10.4%) patients in the tolcapone group, but this difference was again principally owing to the incidence of diarrhoea.

Of note was the higher incidence of depression among placebo treated patients than among tolcapone treated patients (7.3% v 4.8%). More importantly, the incidence of depression of severity sufficient to require treatment was three times higher in the placebo group (18 (5.3%) patients) than the tolcapone group (6 (1.8%) patients).

Overall, 68 patients withdrew prematurely from the study because of AEs: 10 in the placebo group and 58 in the tolcapone group. Diarrhoea was the event most often given as the reason for withdrawal, in 2/342 (0.6%) patients in the placebo group v 40/335 (11.9%) patients in the tolcapone group, followed by nausea, 3/342 (0.9%) placebo v 6/335 (1.8%) tolcapone, and dizziness, 1/342 (0.3%) placebo v 3/335 (0.9%) tolcapone.

Three deaths occurred in the tolcapone treatment group; none was considered to be treatment related. One patient, a 62 year old man, died of a severe cardiopulmonary arrest on day 88. He was not being treated for cardiac or respiratory disease at the time. In addition to tolcapone, he was prescribed clarithromycin and fludrocortisone. A second patient, a 69 year old woman, died of circulatory failure on day 169. This patient had type II diabetes mellitus and hypertension, and was receiving glimepiride, captopril, amitriptyline, insulin, bezafibrate, and ibuprofen concomitantly. She had a mild increase (<3 times the ULN) of hepatic enzymes on day 89, for which no treatment was required. The third fatality occurred in a 58 year old woman with asthma who was admitted to hospital with severe dyspnoea on day 116 and died on day 120. Her death was attributed to a cardiac arrhythmia induced by salbutamol.

Discussion

In this study tolcapone was well tolerated and exhibited a safety profile similar to that reported in studies of patients with more advanced PD.3,4 In particular, increases in liver enzyme levels were consistent with those reported in other placebo controlled trials of tolcapone.2,3,6 In phase II/III studies, for example, a threefold increase in the liver transaminase level was noted in 1–3% of tolcapone treated patients. The proportion of patients in this study experiencing a rise in liver transaminase levels of >3 times the ULN was comparable in both treatment groups. Moreover, serious liver injury and/or hepatic related deaths were not seen in any of the six tolcapone treated patients who experienced these increases. This finding is in accord with existing data showing that the risk of serious hepatotoxicity with tolcapone is small.9

An important finding of this study is that most moderate increases of transaminase levels were transient despite the continuation of tolcapone treatment. Although this does not invalidate stopping rules based on increasing transaminase values (by convention, >3 times the ULN), it does suggest that most moderate increases of transaminase levels do not reflect clinically significant liver injury. Furthermore, the average time to progression to >3 times the ULN was 10 days in those patients with initial increases of 2–3 times the ULN, and more than a month in patients with initial increases of <2 times the ULN. These data indicate that the time course to a significant increase is such that currently recommended monitoring schedules are sufficient to detect these increases and trigger the appropriate response from the prescribing clinician.

Another major finding was that a significant proportion of patients had slightly (<2 times the ULN) raised transaminase levels at baseline, yet none of these patients developed hepatotoxicity. This observation is consistent with more comprehensive data showing that most patients with minimal increases of transaminase levels at baseline do not have advanced liver disease and may not be at increased risk of hepatotoxicity if treated with tolcapone, or with numerous other drugs.14 As recommended by the revised FDA label, patients with baseline transaminases greater than the ULN should have them redetermined, and tolcapone should only be prescribed if the levels return to normal.15

In our study, a considerably greater percentage of patients withdrew owing to AEs from the tolcapone group than from the placebo group (17.3 v 2.9%). Diarrhoea was the most common AE associated with tolcapone treatment and the main reason for early withdrawal from the study (40 (11.9%) patients v 2 (0.6%) patients from the placebo group). Raised transaminases and dopaminergic AEs (that is, nausea and dizziness) were the other AEs that led to greater withdrawal from the tolcapone than the placebo group (4.2% v 1.2%). Apart from these AEs, the tolerability profile of tolcapone was similar to that of placebo and consistent with previous reports, including those involving patients with more advanced PD.2,3,6

Although the finding of increased rates of clinically meaningful depression in the placebo group in this trial was incidental, it is well known that rates of depression are significantly increased in patients with PD.16 Depression can affect quality of life in patients with PD as much as, or more than, the presence of motor symptoms.17 Therefore this signal of potential efficacy of tolcapone in reducing the onset of clinically significant depression in patients with PD may be worth pursuing in future trials.

Two important limitations to this analysis must be considered to place the data presented in a proper context. Firstly, the study on which the analysis was based was designed primarily to assess the long term efficacy of tolcapone in delaying the onset of motor fluctuations when started in patients still in the early stages of PD and therefore was not powered a priori to determine the statistical significance of differences in the rates of hepatotoxicity. Secondly, although 677 patients is a large number for assessing efficacy in a placebo controlled study, it is clearly not sufficient for making a determination of drug safety, especially in regard to a suspected idiosyncratic drug reaction.

In conclusion, tolcapone appeared safe and was generally well tolerated as adjunctive treatment in patients starting treatment with levodopa/carbidopa for symptomatic PD. Mild increases in transaminase values occurred frequently in both placebo and tolcapone groups, although most were clinically insignificant and resolved without drug discontinuation. Although the absolute safety of a drug cannot be ascertained by anything less than long term postmarketing surveillance in a large number of patients, these data, none the less, suggest that the risk of serious hepatotoxicity during treatment with tolcapone in appropriately selected and monitored patients is extremely small.

Abbreviations

AEs - adverse events

ALT - alanine aminotransferase

AST - aspartate aminotransferase

COMT - catechol‐O‐methyltransferase

PD - Parkinson's disease

ULN - upper limit of normal

UPDRS - Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Kurth M C, Adler C H, Hilaire M S, the Tolcapone Fluctuator Study Group I et al Tolcapone improves motor function and reduces levodopa requirement in patients with Parkinson's disease experiencing motor fluctuations: a multicenter, double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. Neurology 19974881–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baas H, Beiske A G, Ghika J.et al Catechol‐O‐methyltransferase inhibition with tolcapone reduces the “wearing off” phenomenon and levodopa requirements in fluctuating parkinsonian patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 199763421–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajput A H, Martin W, Saint‐Hilaire M H.et al Tolcapone improves motor function in parkinsonian patients with the “wearing off” phenomenon: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multi‐center trial. Neurology 1997491066–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adler C H, Singer C, O'Brien C, the Tolcapone Fluctuator Study Group III et al Randomized, placebo‐controlled study of tolcapone in patients with fluctuating Parkinson disease treated with levodopa‐carbidopa. Arch Neurol 1998551089–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dupont E, Burgunder J M, Findley L J.et al Tolcapone added to levodopa in stable parkinsonian patients: a double‐blind placebo‐controlled study. Tolcapone in Parkinson's Disease Study Group II (TIPS II). Mov Disord 199712928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waters C H, Kurth M, Bailey P, the Tolcapone Stable Study Group et al Tolcapone in stable Parkinson's disease: efficacy and safety of long‐term treatment. Neurology 199749665–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suchowersky O, Bailey P, Pourcher E.et al Comparison of two dosages of tolcapone added to levodopa in nonfluctuating patients with PD. Clin Neuropharmacol 200124214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assal F, Spahr L, Hadengue A.et al Tolcapone and fulminant hepatitis. Lancet 1998352958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olanow C W, the Tasmar Advisory Panel Tolcapone and hepatotoxic effects. Arch Neurol 200057263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borges N. Tolcapone in Parkinson's disease: liver toxicity and clinical efficacy. Expert Opin Drug Safety 2005469–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniel S E, Lees A J. Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank, London: overview and research. J Neural Transm Suppl 199339165–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes A J, Daniel S E, Blankson S.et al A clinicopathologic study of 100 cases of Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol 199350140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pocock S J, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics 197531103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russo M W, Watkins P B. Are patients with elevated liver tests at increased risk of drug‐induced liver injury? Gastroenterology 20041261477–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tasmar (Tolcapone) prescribing information Costa Mesa, CA: Valeant Pharmaceuticals International 2005

- 16.Tom T, Cummings J L. Depression in Parkinson's disease. Drugs Aging 19981255–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burn D J. Beyond the iron mask: towards better recognition and treatment of depression associated with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 200217445–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]